Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Shepheard Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

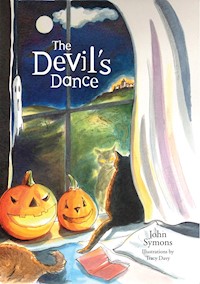

The Devil's Dance transcends categories. It is an exciting, original story, full of menace and very moving. The story is told in turn by two teenagers, Jake and Samuel. It begins with a dream, like a musical overture, which contains the themes to be developed in the rest of the work and describes events that took place two or three hundred years earlier. Gradually the reader understands the horror of what is happening. Jake and Samuel's story unrolls over Hallowe'en, with eerie and, finally, shocking events. The book describes movingly the love of Jake and his mother for his father, who is afflicted by a terrible illness, and their heart-searing loss when he dies. When Jake understands that he may himself inherit the illness and indeed pass it on to his children he struggles to come to terms with the appalling fact. The reader shares the boy's turmoil. The story has several strands: Jake's personal loss; his friendship with Samuel and his loving family; and the mystery of the nocturnal rituals that take place in a deserted hospital on the edge of Dartmoor. Between the episodes of adventure in this well paced story, there are peaceful and pastoral descriptions, particularly of Samuel's home and special family occasions. The boys' nocturnal walks together and alone are also full of atmosphere. The climax of the story is menacing and cruel, and its immediate aftermath no less shocking. The book is charmingly illustrated with line drawings by Tracy Davy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 104

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

OTHER BOOKS BY JOHN SYMONS ALSO PUBLISHED BY SHEPHEARD-WALWYN:

Stranger on the Shore 2009 This Life of Grace 2011 A Tear in the Curtain 2013

The Devil’s Dance

JOHN SYMONS

Illustrated byTracy Davy

SHEPHEARD-WALWYN (PUBLISHERS) LTD

© John Symons 2014Illustrations © Tracy Davy

The right of John Symons to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher, Shepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd.

First published in 2014 byShepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd107 Parkway House, Sheen Lane,London SW14 8LSwww.shepheard-walwyn.co.ukwww.ethicaleconomics.org.uk

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-0-85683-501-8

Typeset by Alacrity, Chesterfield, Sandford, Somerset Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by imprintdigital.com

Ben asked us to tell you this story.It happened a few years ago.Ben’s all right now.He works with Jake’s mum at the hospital; not the one where Jake’s dad died, but the big one in town.

We wrote it, the two of us, straight after that Hallowe’en half-term, taking turns. This is what we wrote, first Jake’s dream, then everything that followed during that week, with no changes, just as it happened.

Ben wants you to read it, and so do we, now that Miss Wheen is dead.The two of us think that she had it coming to her.It was just a matter of time.

Jake and Samuel

Dedicated to the late Dr Geoffrey Hovenden of Barnes, 1906-1993, a wise physician and a good friend.

Contents

Fire, burn!

JAKE’S DREAM

Friday evening

SAMUEL’S STORY

Saturday

Sunday evening

Monday

JAKE’S STORY

Monday

SAMUEL’S STORY

Monday, late evening

Tuesday morning

JAKE’S STORY

Wednesday evening, Hallowe’en

Thursday morning

Friday

Saturday

Fire, burn!

LONG years ago, in the Queen’s Gardens, the embers of a fire are glowing.

Night has fallen. All is still.

From time to time a toddler ventures out of the shadows and nears the fire. He, or she, pokes among the ashes and pulls out a potato or two; usually it is ‘he’ – girls are not allowed out by the villagers this late, especially on a night like this. Gingerly holding his family’s supper in a piece of sacking or the fold of his rough shirt, he scuttles back to one of the tiny cottages set in clusters around the open green.

In these late spring days not many villagers have enough wood left for a fire, so they will not miss the chance of a village bonfire to get a hot meal; even a bonfire like today’s.

A few dogs bark.

Somewhere, in the dark, far away from the firelight, there is whimpering; two animals torn from their mother. The sound comes from the poorest of the village cottages, more a shed than a cottage, a garden shed of cob and thatch, but it is a cottage.

A family lived here for ten years: William, who worked up at Manor Farm, and his wife Emma, and their two children Jacob and Sarah. Emma worked in the scullery at the Manor House until she became ill. But now this cottage shields all that is left of the family.

The villagers cannot afford meat; a few pigeons or rabbits during the winter if they are lucky, if they get away with a bit of poaching; a few fish. Up at the Manor House the Earl and his family gorge themselves on meat, and do all they can to punish poachers. They get fat on it, and their breath stinks because of the excess.

The villagers have cooked themselves only potatoes today, but they have drunk a lot of beer. The Earl provided it. But there is a smell of roast meat hanging over the Gardens. It is faint now but it lingers and clings. It spread across the village this afternoon but, at the time, no one noticed it. There was too much excitement, too much cheering.

The Earl and his wife, Mary, were there. The Countess had recovered enough from the death of their still-born baby and her fever to be able to come. She would not have missed it. Justice, she called it.

No one noticed the smell; so much jeering, so much beer. The Earl struck the spark that started the bonfire, but he and the Countess are now at home in the Manor House. They do not smell this sweet, rich fragrance that all the villagers now draw in with every breath. The Manor House is set well away from the cottages and the green.

‘The villagers can be counted on to do everything appropriately,’ the Earl had said; such a wicked, empty word, ‘appropriately’.

The whimpering grows louder.

No one seems to pay any attention to the sound. Perhaps no one hears it. But suddenly another shape moves out of the dark, across the Gardens, coming from the church, from the side of the village away from the Manor House.

It is a tall lady, in a simple long white woollen robe, the only villager who did not warm herself at the bonfire this afternoon. She was in her cell, the stone room at the side of the church. She was there praying, where she prays every day and every night, hour after hour.

‘Holy Margaret’, they call her in the village and it’s not a joke. But it is not a name that she accepts.

‘I’m just like you,’ she tells them, ‘no better, no worse. Just like you.’

And she believes that, but they do not, and her fame is spreading through Suffolk, through East Anglia.

Holy Margaret is the Countess’s sister, and Holy Margaret didn’t call it justice, what happened on the village green today. She called it murder. She told the Earl and her sister to their faces that it was murder. She told the villagers it was murder.

But still they went ahead, although they dared not harm Holy Margaret. They are all afraid of her; they fear her goodness. Perhaps in their hearts they know she is right, but the beer and the excitement and the horror of Emma drove them on.

The horror of Emma. Just because she was ill, afflicted, in need of help and comfort. Just because she could not control the movements of her arms, her head, her legs. Just because she changed from a beautiful young woman, full of grace and truth, to one three times her age in a few years.

They called her movements the Devil’s Dance, although there was no devil in Emma, only some unknown illness at work.

People said she brought bad luck. But she did not bring bad luck; she merely suffered it, the worst luck of all when William died two years ago and left her ill and unable to cope with her two babies. Holy Margaret helped. As her fame grew, people brought her gifts of food and clothing and she met Emma’s needs as well as she could.

And then the Countess’ sixth child died in childbirth. ‘The evil eye,’ she said. They all began to say it in the village. And there wasn’t a priest at the church to tell them that there is no evil eye, that the Devil was defeated by Christ when he gave Himself for us all on the Cross. The priest of the village lived hundreds of miles away; he never visited the parish; he just received the priest’s stipend. There was only Holy Margaret, and because she was a woman no one paid attention to what she said.

‘The Devil is defeated,’ she said. ‘Emma needs help, Jacob and Sarah need protection.’

And now she is here, Holy Margaret, coming out of the shadows, drawn by the sound of the animals who have lost their parents, Jacob and Sarah. Holy Margaret will not let them die.

As she enters the cottage, the whimpering ceases. They know Holy Margaret. They love her. They fall on her and she embraces them. She takes them, Jacob by her left hand and Sarah by her right, and she leads them across the Queen’s Gardens to her cell. She leads them openly, defiantly. In her pure contralto voice she sings an ancient hymn so that all the villagers will know the truth they must see now or will realise when they, too, face death, that they have done wrong, a great wrong, and that God has not deserted his children, William and Emma’s children.

Holy Margaret comforts Jacob and Sarah.

‘Get these blankets about you,’ she says, ‘good woollen blankets, wool from Norwich from my brother’s farm.’

She settles them quietly and they fall deeply asleep. Then Holy Margaret silently slips into the church. She kneels before the tall carved wooden screen on which is set the statue of the One who was also tied to a stake but crucified, not burned like Emma, like so many before her and a few later in East Anglia.

‘If You are here,’ she says to the One before her, ‘and You are here, look upon these children and their parents. Do not forsake them.’

And the One to whom she prays will never forsake them.

JAKE’S DREAM

Friday evening

‘WAKE UP, Jake,’ says Mum. ‘You’re having that dream again. Samuel’s here with Gip to see if you want to go with them for their last walk up on the moor.’

I get up to go with Samuel and his terrier.

This is Samuel’s story as well as mine but Samuel doesn’t know about my dream.

Mum’s just come back home from work at the hospital and I’d fallen asleep by the fire with the television playing and with Felix the cat on my lap. He loves that chair, his chair, really. Whenever I sit there he comes to take possession of it through me.

Mum knows what the dream is, about the bonfire and the holy lady rescuing the children after their father died and their mother was burnt alive. I’ve had it quite a few times, especially before Dad died. It comes much less often now that I understand things so much better.

But we know that it isn’t just a dream, Mum and I. We both know that Holy Margaret did save Jacob and Sarah, and that Emma was my great-great (how many times great?) grandmother, three or four hundred years ago.

Burnt.

We have stopped having bonfires on Guy Fawkes night. Mum and Dad and I used to love them so much in the old days, before Dad got so unwell.

SAMUEL’S STORY

Saturday

IF YOU GO to the shops in October, you’ll see them there. Black skeletons hanging from the ceiling. Hollow eyes, skulls, ribs, jangling legs, arms hanging loose. Grins on their lips, but there aren’t lips – just teeth, gawping naked teeth. You’ll see them there, dangling up on wires over the bright orange pumpkins.

‘Grown in Britain,’ it says, but I’ve never seen a pumpkin growing here. All stacked up where the vegetables normally stand. And the skeletons hanging above them, swaying slightly. I pointed them out to Carrie and Zeb, my kid sister and brother, as the legs seemed to twitch in the air, and they ran away and looked for Mum.

Mum’s already pushing the trolley up past the fish and meat counter. She knows where everything is, everything we need and can afford. There won’t be money for pumpkins – £5 each, it says, and it looks good value to me. Huge they are, the size of four footballs, but all lopsided, laughing at you, sneering at you even before they are hollowed out, before they have the eyes and lips cut out and the candle put in.

‘Those pumpkins will come and get you,’ I whisper to Zeb, but Carrie takes him by the hand and they go on to join Mum.