7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Dog Sitter Detective

- Sprache: Englisch

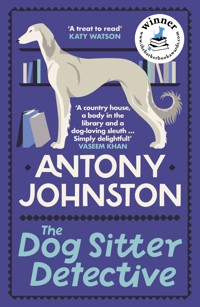

Penniless Gwinny Tuffel is delighted to attend her good friend Tina's upmarket wedding. But when the big day ends with a dead body and not a happily-ever-after, Gwinny is left with a situation as crooked as a dog's hind leg. When her friend is accused of murder, Gwinny takes it upon herself to sniff out the true culprit. With a collection of larger-than-life suspects and two pedigree Salukis in tow, she is set to have a ruff time of it.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 338

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

3

The Dog Sitter Detective

ANTONY JOHNSTON

For Connor and Rosie, the Handsome Gent and the Little Madam, whom we miss every day

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

‘I’m afraid there’s no money, Gwinny. You’ll have to get a job.’

I stared dumbfounded at Mr Sprocksmith, our family solicitor and the duly appointed executor of my father’s will, displaying his most perfectly sympathetic expression. We’d known one another our whole lives, his father, Sprocksmith senior, having served my own father before him. No doubt he anticipated I’d take this news on the chin, which I like to think is still strong even after all these years, and remain stoic.

That’s probably why he yelped in fright when I leapt out of my seat and slammed my hands on his desk, spilling our cups of tea.

‘A job? No money? What the hell are you talking about? Daddy was loaded. You’ve seen our house.’ It was true; Henry Tuffel had made a small fortune in the City. As his daughter and only living relative, I’d expected to inherit quite a sum. But now here was Sprocksmith, telling me there was nothing.

He winced and attempted to wipe up the tea, first with his desk blotter – when that failed, a handkerchief. ‘The house is where your family’s money is tied up, I’m afraid. Your late father liquidated his portfolio after your mother passed, and you’ve both been living off it ever since. His bank savings now amount to …’ He threw the blotter and handkerchief in the wastepaper basket, adjusted his glasses and peered at his notes. ‘Four thousand, one hundred and eighty-two pounds.’ He traced a finger down the page. ‘And sixteen pence.’

Sprocksmith handed me a few stapled sheets of paper. The Matter of the Estate of Henry Wolfram Karl Siegfried Tuffel and its Bequeathal to Guinevere Johanna Frida Anja-Mathilde Tuffel. It was disappointingly thin. Where was the brick of printed paper I’d been expecting? Was this really it?

I threw the pages down on the desk and paced in frustrated circles around his wood-panelled office, waving my arms in a passable impersonation of a deranged windmill and barely missing several bookshelf ornaments. ‘The old misery didn’t say anything to me. He carried on like he was still loaded. For God’s sake, we had dinner at Antoine’s just the other week.’ I turned on my heel and fixed Sprocksmith with a determined glare. ‘How much is the place worth?’

His chin retreated into his ample neck. ‘Gwinny! Surely you’re not proposing to sell your family home?’

‘In case it escaped your attention, Sprocks, I am the family now. No siblings, no husband, and I’m hardly about to get knocked up at my age. How much?’

He floundered. ‘I – I couldn’t possibly say. I don’t think the house has ever been evaluated since Mr Tuffel bought it, after the war. Given its size and location, one would normally assume it could fetch a good price. Chelsea addresses remain desirable.’ He opened his mouth to continue, then clamped it shut.

I wasn’t having that. ‘Out with it. What do you mean, normally?’

His tone was reluctant. ‘The last time I visited, it did seem rather … in want of attention.’

I wished I could argue, but he was right. The roof was badly in need of repair, the kitchen was stuck in the 1970s (and that was positively futuristic compared to the electrical wiring), none of the doors closed without the aid of a shoulder … I’d intended to get it all looked at for years, ever since I moved in following my mother’s death. But caring for my ailing father had turned out to be a full-time job, and one distinctly less fun than the acting career I’d put on hold ten years ago to look after him.

‘It’ll be fine,’ I said, waving away Sprocksmith’s worried expression. ‘Everyone wants to be on Grand Designs these days, anyway. All they’ll care about is the shell and the location. I’ll auction off the contents, flog the place, and move back into my own flat.’ His office window overlooked Cavendish Square Gardens, and outside the afternoon was turning dreary and grey. The great British summer.

Sprocksmith rustled papers and cleared his throat. I took the hint. ‘What now?’

‘I’d need to confirm precise figures, but as I recall the rather large mortgage on your Islington property still has eight years until completion, and the rent you charge your tenants is … well, have you ever wondered why it’s never been unoccupied?’

The first drops of rain fell, leaving only the hardiest dog walkers in the park. ‘Sprocks, you could offer Londoners a broom cupboard with no door and there’d be a queue down the street.’

‘Precisely my point, and one you’ll recall I’ve made for many years. Your continued refusal to raise the rent has failed to create any appreciable cash buffer. Absent even those small payments, whatever you make from selling the house in Chelsea will be swallowed up by the flat in Islington. It’s doubtful you’d even fully settle the mortgage. You’ll have lost your largest potential asset for no particular gain.’

I turned from the window, conceding. ‘So what do you advise?’

‘Live in the house, and undertake repairs by raising your flat’s rent sufficiently to cover those costs, as well as your own standard of living.’

‘And what sort of rent increase are we talking about?’

Without hesitation, making me suspicious that Sprocks had already performed this calculation in anticipation, he said, ‘Four hundred and twenty per cent.’

‘Out of the question,’ I choked.

‘It would still be at the lower end of comparable properties.’

‘No. I couldn’t do that to my tenants. There must be another way to square all this.’

He shrugged. ‘Then we return to the prospect of gainful employment. Surely you can go back to treading the boards?’

I shot him a withering glare. ‘Oh, Sprocks. Darling old Sprocks. If you knew anything about show business, you’d know that roles for sixty-year-old women who haven’t stepped in front of either an audience or camera for ten years are rather thin on the ground. People forget about you very easily, and by the time I quit to look after Daddy I’d already been hanging on for years by the skin of my teeth. All I’m good for now is playing the one-line grandmother whom all the wrinkle-free and glossy-haired bright young things cheerfully ignore.’ I ran a hand through my own hair, short and white. ‘Bloody hell, I’ll have to start dyeing it again. At this rate the only thing I’ll be good for is catalogue modelling.’

‘I’m sure that’s a perfectly respectable line of work,’ Sprocksmith squirmed.

I marched over to his desk and held out my hand. ‘Be quiet, you chinless wonder, and just tell me where to sign.’

CHAPTER TWO

The drizzle stopped as I emerged from Sloane Square Tube. Turning off the King’s Road into Smithfield Terrace, I approached my father’s house. My house, now. I had to remember that.

I tried to look at the place as a stranger might see it, or better still a prospective buyer. From the outside it looked respectable enough. Three storeys plus basement, white-fronted and black-railed, every bit the traditional London townhouse. It even had a parking space out front. Yes, the porch tiles would appreciate a little TLC. So would the window frames, but a new lick of paint would see them right. Well, apart from the one that leaked, in the first-floor reception. And the one that required a screwdriver to open, at the back. Those would need to be replaced. As would the missing ironwork on the basement stair. And the guttering below the dormer window. And the dormer window itself, which had started to stick as badly as the bathroom door.

Still, though! Surely it wouldn’t take much for a decent tradesman to make it presentable again. I fished in my bag for the door keys, ready to assess the interior with a new perspective. But by the time I found them, to my dismay and somehow without making a sound, the Dowager Lady Ragley stood guard between me and the sanctuary of my front door. Despite her age, the widow dyed her hair to match her perpetually black wardrobe, and today it was scraped up into a tight bun, signalling she meant business.

‘Guinevere, my dear. Are you well? My continued condolences, of course.’

‘Thank you, my lady.’ She insisted on being addressed properly, even though she’d now been a dowager four times as long as her late husband had ever been a baron. ‘As well as can be expected.’

‘I’m so very glad to hear it. In which case, I would like to have a friendly chat about your property.’

I’d have gladly taken a hot poker to the eye before engaging in that particular conversation, a preference I’d attempted to show by avoiding Ragley, who lived next door and shared the courtyard passage between our houses, on the fourteen previous occasions she’d tried to corner me on the subject. This time I decided to wind up the old nag.

‘I’m sorry, my lady, you must excuse me. As it happens, I’m expecting a man this very evening to discuss his buying the place.’

Her face, normally white as the lace at her cuffs, took on an indignant colour. ‘A man? A man? What man? Buying the place? What man?’ she blustered.

I adopted my most disarming smile, the one I used to pull out for directors when I wanted to change my lines but make them think it was their idea. ‘I don’t recall his name; I have it written down somewhere. But I’m sure he’ll be a delightful neighbour. I believe he sells used cars.’

The Dowager’s eyes widened, then narrowed. Perhaps she realised she was being wound up. ‘Dear girl, I consider that we have all been very patient with you these past years, knowing your first obligation was to care for Mr Tuffel. Naturally we understand your grief. But it is now time to consider your obligation to the street, and its good people in residence. When one suffers, we all suffer, and our own properties are increasingly at risk of devaluation.’

I resisted the urge to roll my eyes. I’d known that was the real reason behind the Dowager’s concern, of course. The condolences she ‘continued’ to offer hadn’t been all that generous to begin with, even immediately after my father died. And though she referred to the street as a whole, I knew her use of ‘we’ was as much royal as it was collective.

‘I understand, my lady. And once I’ve actually buried my father, dispensed with all the matters arising from his estate and given the tax man his pound of flesh, I’ll be sure to get right on it.’ There was no use playing the guilt trip card on the Dowager, who’d already buried her own parents and a husband, but I was starting to see red. ‘For now, I have a house to clean and declutter. Unless you’d care to join me in scrubbing out the bath?’

I might have laughed at the expression of confusion and disgust on the old widow’s face if a familiar voice hadn’t distracted us both.

‘Don’t worry, sweet pea, I’ll get stuck in with you. You find the Marigolds; I’ll put the kettle on.’

Tina Chapel, smiling and radiant as ever, came to my rescue with a protective hand on my shoulder. I’d texted her upon leaving Sprocksmith & Sprocksmith, inviting her round for tea and a morale boost. Even in her ballet flats, the tall Caribbean actress towered over both of us, and Lady Ragley’s face cycled through a series of mixed emotions before settling on a reluctant smile.

‘How lovely to see you, Ms Chapel. You light up our street with your presence.’ Laying it on a bit thick, if you asked me, but I was grateful for anything that got the Dowager off my back. ‘Are you not working today?’

‘Our final curtain was last Saturday, my lady,’ Tina beamed. ‘I’m sure James can tell you all about it. He was in the audience, with a beautiful young companion I might add. Do give him my regards.’

‘Was he, indeed.’ The Dowager frowned at the mention of her son, sniffed and turned back to her house. ‘Always a delight, my dears. Good day.’ She retreated through her front door, somehow slamming it shut without making a sound.

‘There are times I think she’d rather have you for a neighbour than me,’ I said, finally removing the house keys from my bag.

Tina smiled wickedly. ‘Not after she’s finished grilling her son about his non-existent new girlfriend.’

‘You’re so cruel,’ I laughed.

‘It’s why you keep me around. That and my uncanny generosity.’ She carried a canvas tote on her shoulder, and now she tipped it open to display the contents.

I peered inside, and a tiny, involuntary squeak escaped my lips when I read the words 500 pieces printed on the side of a box. Without another word I unlocked my front door and led Tina into the house. My house.

In some ways, crossing the threshold felt like entering a very different place, one completely separated from the exterior; as if, rather than a door, we’d walked through a portal to another house altogether.

Where the outside was somewhat dishevelled but bright and upright, inside the house was somewhat upright but several leagues, and decades, beyond ‘shabby chic’. Fifty years’ worth of the Financial Times spilt out from the study into the hallway and sitting room, which was itself stuffed with piles of jigsaw puzzle boxes. Bookshelves lined every room, stacked two, three, five deep with volumes of law and finance, history and philosophy, in no order discernible to anyone except Henry Tuffel himself, and mixed liberally with paperbacks ranging from Frederick Forsyth to Danielle Steel.

Upstairs, closets and wardrobes burst with a lifetime of clothing ranging from my mother’s glamorous evening wear to my father’s daytime casuals, a decades-buried time capsule of style and fashion. Much of the clothing was bagged, some was moth-eaten and all of it was useless to me. My own possessions were crammed into a second-floor bedroom, leaving barely enough space for the bed. Even when my father gave me the option to expand into another room, I’d declined because I never intended my stay to be permanent. The plan had always been that I would eventually return to Islington. Besides, there was nowhere to expand into that wouldn’t require yet more shuffling of clothes, furniture and old dog beds. Even finding a flat surface to store things on was an endeavour, covered as they were by letters, newspapers, books, magazines, jigsaws and the numerous souvenirs, mementoes and gifts my parents had collected during their lives.

Heinrich von Tüvelsgern had immigrated as a young child with his parents, when they fled to England before the outbreak of World War II. In Germany, our family had been wealthy and our name well-regarded, but my grandparents left with barely a suitcase between them. Fortunately, their newly Anglicised son ‘Henry Tuffel’ was possessed of a keen intelligence, a handsome profile and charm to match. He grew up here and made a great success of his new life through smart investments, good connections and occasional diplomatic favours to the Foreign Office about which my late mother Johanna (another escapee from the Third Reich, who’d met Henry here in London during the war) always refused to answer questions.

So much history, I thought, and all of it wrapped up in this house. At the time it seemed to matter so very much; now it was nothing but dusty memories on the swirling winds of my own mind. When I was gone too, who would be left to remember any of it? Who would even want to?

I led Tina into the kitchen, the one space I’d managed to keep clean and orderly for the past ten years. She stole a glance into the sitting room, where my father spent most of his last days, and where the scattered evidence of his removal by ambulance medics remained.

‘Oh, you poor love,’ she said. ‘You haven’t done anything since … well, since. Have you?’ In the kitchen, she began to make tea, not needing to be told where anything was. We’d been friends for so long, she knew the house as if it was her own.

I eased myself into a wooden chair and sighed. ‘It’s all right, you know. I promise I won’t fall to pieces if you say it. Daddy’s dead, and it was a long time coming. You saw what he was like at the end. There was nothing left of him, not really.’

She smiled sympathetically. ‘There was enough for him to know you were there, I’m sure.’

I wasn’t convinced of that, but there was no point arguing. It wouldn’t change anything, and I didn’t want to upset Tina. She was the first friend I’d called when I found Henry unresponsive in the sitting room, and the only one at all who’d been to visit since then.

‘Anyway,’ I said, as brightly as I could manage, ‘no time like the present, and if I’m going to sell the place I’d better get on with it.’

A teaspoon tinkled on the counter as she fumbled it and stared at me in disbelief. ‘Sell? You can’t be serious.’

‘You’re as bad as Sprocks. It’s only a bloody house. The biggest problem will be finding someone who actually wants to take it on. A fixer-upper, I believe they call it nowadays.’

She recovered the teaspoon and resumed brewing. ‘Let’s be honest, it’s more like a tearer-downer. You might be better off gutting the whole place and starting again. Still, I suppose one way or another you’ll have to spend the money, whether you keep it or sell it. How much did he, um … you know …’

‘Oh, darling, that’s why I asked you to come round.’ I accepted a cup and waited while she joined me at the kitchen table. ‘It turns out I’m broke. Four grand and this run-down old house. That’s all he had left.’

She reached across the table and squeezed my hand. ‘Oh, God, I’m sorry. How much do you need? I’ll call my bank—’

‘No, no, that’s not what I meant.’ I pulled my hand away. ‘I asked you here to cheer me up, not for charity.’

‘It’s not charity. It’s helping a friend in need. I don’t expect anything in return.’

I smiled. ‘That’s literally what charity is, you silly woman. It’s a good thing other people write our lines, isn’t it?’

Tina laughed, and despite everything I found myself joining in. Egged on by each other, we giggled and howled for a full minute, until we were both wiping tears from our eyes. ‘Oh, Christ,’ I said between sniffles. ‘It wasn’t even that funny.’ I reached for her tote bag. ‘Come on then, let’s see this puzzle.’

It was, as the box side promised, a five-hundred-piece jigsaw. The picture was an aerial photograph of Neuschwanstein Castle, the operatic Bavarian folly built by Ludwig II. I’d visited once with my parents, and the guide had enthused about how its design inspired the Walt Disney castle image. Even as a child I’d been sceptical that was true, but it made for a good story, as did the legend that it took so long to build, Ludwig himself only slept in the castle for one night before he went insane and was deposed.

The picture reminded me of my parents, and Germany, and how the memory of people might outlive them.

‘It’s perfect,’ I said. ‘You know me so well.’

Tina stood and kissed me lightly on the head. ‘Yes, I do. Now grab some Marigolds, bring your tea and let’s get stuck into the bathroom.’

We spent the rest of the afternoon shuttling between the main bathroom and the kitchen, scrubbing, making tea, drinking tea, scrubbing some more, making more tea and discussing Tina’s imminent wedding. At the weekend she would marry Remington De Lucia, a handsome Italian olive oil magnate whom she’d met the year before while she was on holiday in San Marino. He lived in the tiny principality, but Tina had no intention of moving there. Remington, meanwhile, was equally adamant he wouldn’t spend all his time in cold, wet England. So they’d agreed to split their time between the two places. When I raised an eyebrow at this questionable level of commitment, she shrugged. ‘It’s my fifth, and his fourth. I enjoy his company, both in and out of bed, but I’m not about to become a doting housewife. We’re prenupped to the hilt anyway, in case things go south.’

‘How romantic,’ I laughed. ‘Does he have a brother I could marry for his money, instead?’

Tina frowned. ‘Only a sister, Francesca. She’d have buried me a hundred times over by now if looks could kill. Luckily, she’s not coming to the wedding. None of his family are.’

‘That’s a bit cold, isn’t it?’

‘One gets blasé after the first few. Besides, there’ll be plenty of guests from our lot. Poor Mrs Evans is already running around like a madwoman organising staff.’ Mrs Evans was Tina’s doughty housekeeper, a formidable woman who kept her country house, Hayburn Stead, running like clockwork.

‘Be careful you don’t overwork her.’

‘I’m not sure that’s possible,’ she said, scrubbing at a plughole. ‘They’ll carry her out of Hayburn feet-first in a box. Pass me the scouring powder.’

By early evening we felt blasé about our own progress in the bathroom. With one mostly clean tub and half a clean shower under our belts, we decided to call it a day and take a walk in Kensington Gardens.

‘I think old Sprocks may have been right,’ I said as we ambled toward the bandstand. ‘I used up most of my own money while taking care of Daddy, and I didn’t realise he was draining his savings to pay for the household too. A few thousand won’t pay for all the repairs the house needs, let alone cover my bills while it’s being done. I’m just not sure I can face trying to revive my career.’

Tina put her arm around my shoulders. ‘You had steady work for thirty years, sweet pea. It shouldn’t be that hard to get back into it.’

‘Twenty and a bit. The last ten years were pretty thin on the ground.’

‘That’s because you were middle-aged, love. Now you’re distinguished. Look at you: good bones, clear eyes and still the same dress size as when you were twenty. Call your old agent, whatsisface, and get back on his books.’

‘That might be tricky, considering I attended his funeral five years ago. Don’t you remember? You were there too.’

‘Was I? Oh, dear. Sorry.’ She grimaced.

‘Which means I’ll have to find someone new to take me on, and it’ll take more than being “distinguished” to convince them. I’ll need to grow my hair out and dye it, for one thing.’

‘Oh, pish. There are more roles for women our age now than ever before. Before you know it you’ll be on Loose Women talking about your latest show and laughing about the good old days of your menopause.’ I thought that was about as likely as going into space, and it must have shown on my face. Tina laughed. ‘Look, you’ll be fine. If you’re that worried about your hair, you can borrow some of my wigs – oh!’

A huge black Labrador burst from the trees, barking furiously and galloping across the bandstand clearing. Tina yelped and flinched as it raced toward us, barking and slobbering. I instinctively moved in front of her and locked stares with the dog. I maintained eye contact and jerked a raised finger in the air as if to puncture the sky, with a sharp warning ‘Ah!’ bark of my own.

The dog skidded to a halt, its eyes fixed on me and its rear end quickly hitting the grass. I lowered my finger and growled, ‘Down!’ with as much force as I could muster. The dog hesitated, uncertain whether to obey. I made sure there was no doubt by leaning towards it, widening my eyes and refusing to look away. The Labrador shuffled its backside, then finally lay down and let its ears flop, suddenly fascinated by the grass.

‘Well, bugger me sideways,’ said a stocky man jogging towards us from the trees, waving his arms around. One hand held a dog lead, dangling uselessly. The other held what appeared to be a piece of sliced ham. ‘Sorry, ma’am. Ronnie doesn’t normally break away like that. Just being friendly.’

He was around our age, with a grey moustache to match his short, clipped hair, and bright blue eyes. He was also a good head taller than me, but I stepped forward to admonish him anyway. ‘Where do you think you are, Wimbledon Common? That’ – I pointed at the lead in his hand – ‘is supposed to be around its neck, if you can’t keep it under control. And that’ – I pointed at the limp slice of ham – ‘is clearly useless.’ He didn’t move, so I gave him the same unblinking stare I’d used on his dog and barked, ‘Well? Get to it!’

As if a spell had been broken, he quickly crouched and slipped the slice of ham to the Labrador, who gratefully inhaled it. While the dog was occupied, he clipped the lead onto its collar, gabbling the whole time: ‘Yes – sorry – you, well – I mean – sorry, you’re – Gwinny Tuffel, isn’t it?’ He stood, looked over my shoulder and started. ‘Blimey, Tina Chapel too. Saw you in Macbeth at the Richmond Theatre. Wonderful stuff. Commanding.’

Tina stepped forward and automatically slipped into meet-the-punters mode. ‘That’s so kind of you to say. Really, it was a dream role, and of course to play opposite Sean was a delight. Would you like a photo?’

I tutted and glared at the dog owner. ‘Never mind a selfie. Keep your dog on-lead and under control. What if we’d panicked and it had bitten one of us?’

‘Oh! Ronnie wouldn’t do that.’ As if in agreement, the Labrador took two steps toward me and gazed up, its tongue and tail both thoroughly excited. ‘Gets over-excited from time to time, see. Look, maybe he recognises you from the telly, ha ha!’

I sniffed at his attempt to lighten the mood. Undeterred, he cleared his throat and offered his hand. ‘Unreserved apology offered, ma’am. Won’t happen again. DCI Alan Birch, retired. At your service.’

‘Ex-police? I assume the D doesn’t stand for “dog squad”.’

‘No, ma’am. “Detective”,’ said Birch, his cheeks reddening as Tina stifled a giggle.

I relented and shook his hand. ‘Well, DCI Birch, retired, I accept your apology. But if I see Ronnie out of control again in the Gardens I’ll report you to your former colleagues. Is that understood?’

‘Absolutely,’ he smiled. ‘Sound like my old DCS, you know. Think you two would have got along. Ladies.’ He nodded goodbye and led Ronnie away, back into the trees and toward the Long Water.

I watched him go, until Tina elbowed me in the ribs. ‘Now there’s a man you could marry for more than money. What lovely eyes.’

‘Oh, pull your knickers back up,’ I said. ‘Besides, he was wearing a wedding ring. Much like the one you’ll be putting on at the weekend, need I add.’

‘You noticed the ring, did you?’ she teased.

I pouted. ‘Hard to miss when he was holding a piece of sliced ham in the same hand. Now come on, I’ll walk you home and you can tell me more about these wigs.’

She did, and also offered to drop my name to producers she knew. Some of them would be at the wedding, too. It was very kind of her, and I was grateful, but I knew it wouldn’t lead anywhere. Ten years was a long time in show business, especially for a character actress. I didn’t have any major lead roles on my résumé that I could trade on nostalgically, and despite her optimism, the chances of me landing a lead these days were all but non-existent. Even Tina, who was tall, beautiful and famous, was mostly doing stage now. A new breed of producer had taken over in TV and film, one that would surely look askance at a woman my age trying to make a comeback.

Just thinking about the time and energy it would require to revive my career all over again exhausted me. Looking after my father really had been a full-time job.

Back at home, with late-night TV droning in the background, I cleared some space in the sitting room and made a start on the Neuschwanstein puzzle. I thought back to when I was a girl, in this very room, and would watch him build his favourite pictures. He’d been a jigsaw buff all his life, enjoying making order from chaos. I thought it was a silly way to pass the time, especially when he made such minimal progress each night. But he’d smile and wag his finger, saying, ‘A house is built one brick at a time.’

Nevertheless, despite his enthusiasm I hadn’t caught the bug. I was much more inclined to read his books, especially the pulp thrillers he devoured. My mother loudly despaired of his taste in fiction, being more inclined to the Regency and Victorian classics she made me read. They were fine, but it was the cryptic titles and garish, exciting covers of my father’s paperback collection that I found irresistible. When I moved back home to care for him, I immediately caught up on the books he’d collected in the decades since I’d left home. But his buying pace had slowed dramatically, especially in recent years, and twelve months later I’d burnt through the lot. Looking around for something else to do in the evenings besides collapse like a sad sack in front of the television, I found myself drawn to the stacked puzzle boxes. One in particular had caught my eye, a painting of an idyllic English fête on a bucolic village green. I was almost certain it wasn’t a real place, but I didn’t care. Stuck in Central London for the foreseeable future, with only one inevitable ending in sight, I’d been only too happy to lose myself in the fantasy of an England that never was.

Months later I was getting through his puzzles at the rate of one a week, and it wasn’t long before I began adding my own purchases to the collection. Order from chaos.

The Neuschwanstein puzzle from Tina was hardly a challenge at all. I could normally polish off a five-hundred-piecer in a couple of evenings. But it was the thought that counted, and I smiled as I began constructing a top-left corner of blue Bavarian sky.

Spirits lifting, my thoughts strayed to DCI Alan Birch, retired. I would have expected better behaviour from a former policeman. It was a good thing I wasn’t panicked by errant dogs, or more accurately errant owners. ‘A dog’s behaviour is no better than the man who teaches it,’ my father used to say (it never occurred to him that a woman might do the teaching). I’d seen the truth of that saying my whole life, and there was no better exemplar than my father himself. Our family had always kept dogs, and Henry Tuffel was known by the local rescue charities as a soft case for a handsome hound. A suitably boisterous wagging tail could even crack my mother Johanna’s Teutonic reserve. So I’d grown up around dogs, and been the one to help my father train and look after them. Sometimes when I was a child, if he was particularly busy, he’d trusted me to walk them by myself around Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens. His last dog had been Rusty, a Jack Russell. When Rusty died four years ago he’d wanted to replace him, but I put my foot down. By then my father had grown increasingly difficult to care for, and I’d already struggled to cope with his needs alongside those of a dog, even a tired old terrier like Rusty.

Now, with them both gone, the house was silent again. But I couldn’t contemplate getting a pet, not now I found myself needing to find work. That would mean either leaving a dog by itself all day, or giving it to a sitter who’d wind up spending more time with it than I did. It wouldn’t be fair on either me or the dog.

I finished the edge of a corner on the puzzle. Each sky piece was an identical colour, but the shapes were enough for my practised eye to fit them together. I leant back in satisfaction and my thoughts drifted again to that former policeman. I was reluctant to admit it, and still angry at his irresponsible behaviour, but I’d enjoyed being recognised. After more than a decade out of the spotlight, complete with extra wrinkles and grey hair, it was a miracle anyone could still connect me to my ‘screen face’. The observational skills of being a detective, I supposed. A good eye. And Tina was right, they had been a striking bright blue …

I woke with a start and a grunt half an hour later, the TV still talking quietly to itself. Annoyed that I’d fallen asleep, I left the puzzle in place on the table and dragged my tired body through the house’s stillness. Upstairs and past the open door of my father’s bedroom, where I lingered in the doorway. Undisturbed, unused, but not mine. Not yet.

I pulled the door closed and continued to my room.

CHAPTER THREE

On Thursday evening I called at my Islington flat. Tina’s words and offer of help were kind, but I knew that reviving an acting career at sixty, especially after such a gap, wasn’t realistic. I’d have to take Sprocksmith’s advice after all and figure out what to do with this flat.

A four hundred per cent rent hike was out of the question, but perhaps I could raise it by half without scaring off the McElroys. They were model tenants: a young professional couple who moved in three years ago, never caused trouble, never missed a rent payment, and hardly ever bothered me with demands to change this or fix that. I hadn’t even had to call round in almost a year.

Nevertheless, I really did need money. I’d decided that if they baulked, I’d give them notice and ask them to leave so I could sell the place. Mortgage or not, it might bring in enough cash to repair the family house. Then all I’d have to do was sell that in turn and buy something smaller, perhaps another flat like this one.

I’ll be the first to admit I don’t have much of a head for figures, but that made sense. Didn’t it? Well, it was too late now. I’d made up my mind.

I crossed the narrow lobby, nodding at Alfred the concierge, and took the lift to the second floor. I had a front door key, of course, but it would be rude to just walk in unannounced, so I rang the doorbell.

Nobody answered.

It suddenly occurred to me that I hadn’t given any warning I was coming. Silly old Gwinny! The McElroys might be out at dinner, or a disco, or wherever else young people go these days to live it up. I should have phoned, or even emailed (which I’d made myself get comfortable with while caring for my father, though I still preferred using the phone). I decided to go home and do that right away, making arrangements to visit next week instead.

But then I heard a sound inside the flat. Shuffling, and keys jangling. The door opened, and Mrs McElroy smiled wearily. She didn’t move in for a greeting kiss, as the manoeuvres would have been somewhat awkward.

‘Ms Tuffel,’ she said. ‘You should have called ahead; I was just running a bath to take the weight off. What’s up?’

I stared at the pregnant young woman’s enormous bump and groaned.

On Friday afternoon I attended my father’s funeral. A quiet affair, but well-attended all the same. I was mildly surprised to see so many political faces from the past, in addition to the few family friends and City colleagues who still lived. Henry Tuffel had been in decline for years, and they’d all said their final goodbyes long ago. Everyone was sorry; everyone was sympathetic; no one was surprised.

My father had made peace with his imminent passing in typically idiosyncratic fashion. One of the last things he said to me was, ‘Everything I loved about the world is gone.’ Strange as it sounds, I think he was trying to reassure me he was ready to go. I didn’t mention it in my eulogy, though. Funerals are meant to be sad, not bitter.

Later, I placed his ashes on the mantelpiece next to my mother’s. He’d asked me to take them both to the Tegernsee, when it was time. One of the few things left in the world he did still love.

I changed out of my funeral clothes, dressed for housework and began to scrub at the shower.

On Saturday morning I attended my first audition in ten years. A casting director for a new TV drama had called the evening before, while I was Marigolds-deep in that shower, and invited me to a Soho office the next morning. Tina’s name wasn’t mentioned, but as I hadn’t even begun calling agents yet it didn’t take a genius to detect her invisible hand. On a Saturday morning, though? And this Saturday morning of all days? It really took the biscuit.

Nevertheless, I couldn’t afford to turn it down, either figuratively or literally. Figuratively, because if I did word would quickly spread that I wasn’t serious about reviving my career after all. Literally, because I couldn’t now bring myself to extort or evict my Islington tenants, with their baby on the way. Elbowing my way back in front of an audience was the only way forward I had left.

Besides, Tina’s wedding wasn’t until two in the afternoon. I could do the audition, run home and still have time to drive to the country house.

I was a bundle of nerves at the reading. It had been so long, I’d all but forgotten how anxious they made me. For some actors, a live set is a nightmare, with picture and sound rolling, the camera ready to capture every movement, sound and potential mistake. They’re more comfortable on stage, where they feed off an audience’s energy, able to hide behind the mutually accepted artifice, with everyone a step removed from the truth. But the camera is an audience, too, and one that’s always brought me to life. Inside every actor is a ticking time bomb of adrenaline, struggling to explode; on screen, our job is to let that explosion occur slowly, only when we allow it, otherwise projecting nothing but stillness and calm. The energy of that struggle, and the closeness of the lens, drive me. Knowing the merest flick of a lash will move mountains is a feeling like no other.

Today’s reading would have been lucky to nudge pebbles.