Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

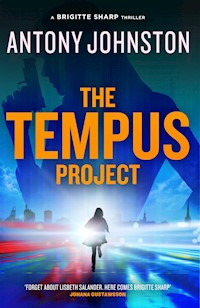

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: A Brigitte Sharp Thriller Book 3

- Sprache: Englisch

'In the very top tier of spy fiction' M.W. Craven ONLINE HATE BECOMES REAL When a renegade British officer steals plans for a high-tech weapon that could plunge whole cities into darkness, elite MI6 hacker Brigitte Sharp is sent to get them back. But her mission goes badly wrong. Meanwhile a 'deepfake' video of a senior US politician calling for race war in Europe sends a flood of Americans to join neofascist militias on the continent. The Russians nurse a ruthless grudge against a fugitive whistleblower. In the wings, the Chinese flex their muscles. Everything seems connected…but how? In her toughest challenge yet, Bridge ventures undercover into the heart of the mysterious Patrios network. Her task? To make sense of the growing chaos before darkness and bloodshed engulf Europe. If a powerful enemy doesn't get her first...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 546

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published by

Lightning Books

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.lightning-books.com

First edition 2022

Copyright © Antony Johnston 2022

Cover design by Ifan Bates

Typeset in Minion Pro and Knockout HTF28

All rights reserved. Apart from brief extracts for the purpose of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without permission of the publisher.

Antony Johnston has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as author of this work.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781785633034

Humbly dedicated to the memory of John Le Carré

Contents

Author’s note

Acknowledgements

Other books

1

The shipping container’s door inched open with a grinding lament. It stopped just wide enough to reveal a face Yuri had never seen before, framed by elasticated white plastic.

‘Red admiral,’ Yuri said, quiet but firm.

The man inside the container nodded, satisfied, and opened the door wider to allow Yuri through. He slipped inside, making a mental note to consider making future protocol more secure. Then again, it seemed unlikely he was accidentally walking into a different shipping container whose occupants expected someone to knock on the door, say a code word, then come inside to discuss the results of their torture methods on the pathetic, bleeding prisoner strapped to a chair and whimpering in the centre of the floor.

Still. Moscow rules, as the old guard used to say. Assume nothing, trust nobody.

A second interrogator wore an identical thin plastic full-body coverall. Two to ply their trade on a third, and from what Yuri saw they enjoyed their work. He wondered if red coveralls would make more sense; they were already halfway there. But seeing the pristine white slowly turn crimson, coupled with the awful knowledge of precisely why and how that was happening, probably formed an effective part of their method.

He marvelled at the ingenuity of the set-up. A location as anonymous and temporary as could be imagined, large enough for its intended use but no larger, inside which you could do almost anything. The walls were covered with silver heat-reflective material, and while Yuri wasn’t about to break out his swimsuit, it had kept the temperature above freezing – presumably helped by one of the occupants sweating and screaming in pain for hours at a time. Soundproofing material behind the insulation was supposed to take care of that, though he wondered how successfully it masked the noise. People could be surprisingly loud over nothing more than a peeled fingernail.

The chair looked as if it had been lifted from a dentist. Perhaps it had. Modified for purpose, though. Not many dentists strapped their patients down with leather cuffs over the wrists and feet. Speaking of cuffs, Yuri almost banged his head on two metal restraints chained to the ceiling. He looked down and saw two more chained to the floor.

The first torturer turned from closing the door, saw his expression, and shrugged. ‘Sometimes we make them stand up.’ No further explanation was forthcoming, or necessary.

At the back of the container – behind the chair, so its occupant couldn’t see what was being prepared, because sometimes the anticipation was worse than the final pain – was a portable table with folding legs, the kind one might take camping in the Urals, and upon it a canvas holdall, zip open to afford access to its contents. Most of which were very sharp, though some were deliberately very blunt.

A separate bag, a small backpack, leaned against the back wall. The second man bent down now and from this bag snatched a water bottle, next to which was what looked like a plastic box for sandwiches. The man drank from the water bottle and winked at Yuri. Thirsty work.

There was nothing else in the container, so he turned to the prisoner. A young man, north-east Asian of appearance, perhaps Mongolian or even Yakut. Hard to tell after the beating that had been delivered. He reached out with a gloved hand and tilted the man’s semi-conscious head this way and that. Doing so dislodged blood from the prisoner’s gums as he whimpered in pain, fresh flow escaping the slack corner of his mouth. His eyes swivelled; not the animal, instinctive panic that had probably consumed him earlier that evening, but now the tired delirium of a man who knew pain was merely a state of existence. One with which he had become intimately familiar over the course of the day, and if he had any fear that he might come to know it even more closely in the hours ahead, it was buried so deep within him it wouldn’t surface in time to show.

Still peering at the torturers’ handiwork, as if preparing to grade it, Yuri said, ‘Did he talk?’

‘Eventually,’ said the first. The second hadn’t spoken yet, and showed no intention of doing so. Perhaps this was their thing, or perhaps the mute one was a moron who transformed into a multilingual prodigy when speaking via handheld implements.

The first torturer retrieved a piece of paper from the folding table and handed it to Yuri. A name, and an address. One he expected, the other he did not, but his expression betrayed nothing. He pocketed the note and looked at the prisoner.

‘How reliable is he? I mean…’ Yuri gestured at the blood, the tools, the bodily wreckage. ‘Some people will say anything.’

The torturer shrugged again. ‘That’s why we prefer young targets. You take an old man, someone who’s seen life, and they know this is the end. They tell you nothing, or nonsense, and wait to die. But a young man who thinks his whole life is still ahead of him will play the game. Defy you, then lie to you, then tell the truth because he always thinks there’s a chance he can make it out to fight another day. Maybe even take revenge.’

‘Ah,’ Yuri nodded, ‘naïveté.’ He turned the prisoner’s face towards him, though the man’s eyes still couldn’t focus. ‘He’s right, you know. If you were older, maybe you’d have seen a few of these from the other side. Enough to teach you that escape is for the movies…and revenge is for people who don’t get lifted in the first place.’ He retrieved a folded cloth from inside a coat pocket, shook it out, and clamped it over the prisoner’s mouth and nose.

Now came the final struggle, the absolute fear, the instinct that overrode all pain and suffering and exhaustion. Every last ounce of energy expended to fight for life, desperate for existence to continue, no matter how painful. At last the prisoner’s eyes found focus, his throat found voice, his muscles found strength; reserves previously unknown, depths previously undiscovered, willpower previously untapped, no matter how shallow or weak. Circles of blood stained the cloth, expelled with force from mouth and nose but trapped in its weave. Yuri still wore his gloves, but the cloth wasn’t to remove evidence, it was to prevent spatter and blemish. He needed to be able to walk out of here unmarked and return to polite society as if he’d never left. Blood stains on his shirt cuffs would rather spoil the illusion.

Nevertheless, of course he wanted to do it himself. He was old-school enough for that. It had been a long time since the last time, but the memory came easily, skill and movement that were his to summon. The sensation and experience of killing another human with one’s own hands could never truly be forgotten. Not that it kept him awake at night. He wasn’t a person much afflicted by remorse or regret.

Consumed by revenge, though. The type not found in movies, but in a lifetime of righteousness and anger; that was his strength and his weakness. One day, he assumed, it would kill him. But today it would kill this young man, whose only mistake was being one of a handful of people with the information he needed to enact that revenge.

Light fled the prisoner’s eyes a moment before the fight fled his body. Yuri waited for the final exhalation, and suddenly remembered the pretty young doctor, many years ago in Zurich, who had named it for him: postmortem agonal respiration. A muscular contraction that occurred following cessation of the heartbeat. The shock of his dead father suddenly appearing to breathe had distracted him from the details, to be honest. And later, in Yuri’s hotel room, hadn’t been an appropriate time to ask her to repeat the explanation.

The prisoner relaxed, in the way only a truly dead body could. Yuri removed his hand, leaving the cloth. Instead he took another one, gaily patterned, and mopped his face. That insulation was better than he’d guessed.

The other men were already gathering their tools into the holdall, while removing other items; a metal tube, and a small plastic bottle filled with grey liquid. Yuri asked, ‘How long before somebody finds this container?’

‘Months, maybe years. By then he’ll be long gone.’ The speaking man held up the tube and bottle. ‘Caustic agent. The gas will corrode anything traceable, and dissipate as it escapes the vents.’

Yuri nodded. ‘Fire would attract too much attention.’

‘Exactly. Tomorrow this box begins a long transshipment journey around the world. It will spend months at sea, then a few days at a port somewhere, before transferring to a new ship, where it will do the same again. Two years, if security doesn’t force it open before then. There’s no reason they should.’

‘Good.’ With one last look at the body, Yuri left them to clean down and decontaminate the container with the practised ease of experienced operatives.

He returned to the gate and exited the port. The guards ignored him, as they’d been paid to, and he continued into the night. His hire car was parked a kilometre away, a precautionary habit ingrained over many years. In the distant sky over Hamburg, bright, silent fireworks exploded to celebrate New Year. Yuri allowed himself an internal celebration too, letting fantasies of where tonight would lead, and what would follow, warm him during the cold walk back to his car.

Some people needed to be taught a lesson. He would relish playing the role of teacher.

2

@ToTheFathers

7:00 AM January 1

LAND OF HOPE AND GLORY

NEVER TO BE SLAVES

66408726102204878

16611636666158410

81760216047699996

98452426655275963

31678602813496935

24266552759633167

86028134969356107

29596332133951796

56964998345629311

30163096284016047

Posted via Twitter on the web

Six weeks later

3

It made a nice change to travel on her real passport. No cover ID, no disguise, no fake contact lenses or wigs, just the real Brigitte Sharp. The wrong side of thirty to pass for a student; the wrong side of five-ten to easily blend into a crowd; the wrong shade of complexion to pass for anything other than English, despite the French passport tucked in the inside pocket of her trusty black leather jacket. Twenty years in London would do that to you.

OpPrep had offered to give her a cover identity, a legend as they called it, but it was a half-hearted gesture and there was little point for such a brief trip. Eurostar was running more services now, and she didn’t need to pretend to be someone else today. She was on her way to confront a traitor, hopefully catch him red-handed with an enemy of the state, and take them both back to London by the same route.

Besides, like everyone else on board, she wore a mask. Even if Simon Kennedy had stood up from his seat at the other end of the carriage, turned around, and looked her straight in the eye, he wouldn’t have recognised her. They worked in different departments and, despite Bridge’s limited fame within SIS, there remained thousands of officers and staff who not only didn’t know her but who, upon seeing her pale skin, black hair, black clothes, black boots, and generally surly demeanour, would place her in many other categories before thinking to file her under ‘intelligence officer’.

She’d never heard of Kennedy either, before Giles Finlay summoned her to a meeting in Broom Eight two days ago. Giles was head of the CTA, MI6’s Cyber Threat Analytics unit; at least she assumed he still was, despite several promotions in the years since he’d created it. Bridge wasn’t sure of his official title these days, but he remained her boss – despite her own promotion to lead SCAR, the inter-agency board she’d helped bring into being. Shared Cyber Anti-terror Response was created to pool developments across SIS, MI5, GCHQ, and the Ministry of Defence, to stay one step ahead of attacks and espionage. Bridge hadn’t wanted to lead it, but then she had, but then it had been taken away from her, but then that had turned out to be a sort of cruel test on Giles’ part. She still hadn’t fully forgiven him. But much of her time since had been spent either working at home or fucking her new CIA boyfriend at his home, both activities enjoying increased frequency thanks to the pandemic, and they’d brought with them new problems. First among them was the lack of sleep she endured these days, and not only for the most obvious reason. It was a rare night that Bridge didn’t wake up several times from violent, frightening nightmares. Karl was sympathetic, but nobody’s patience was endless.

Nevertheless, Giles remained her immediate boss, and when he summoned she attended – in this case to one of the smaller secure briefing rooms at SIS headquarters in Vauxhall, with a small conference table and space for half a dozen people. Like all Brooms it was soundproofed, windowless, and hardened against wireless signals. A screen and keyboard at one end of the table were connected by physical wire to their computer, which lived in a secure SIS server facility in the building’s basement. When not in use, every Broom’s screen looped through the same screensaver, a slow, gentle pan over deep green fields that Bridge had come to loathe within months of joining the Service. Years later, and despite several generations of computer upgrade, it hadn’t changed. She often wondered if someone in the IT department was playing a joke.

Bridge and Giles entered to find Emily Dunston already waiting. Dunston was Head of Paris Station, controlling the Service’s activities in France from her London desk. She drummed her fingers on the table impatiently and glanced subtly at the computer screen – which to Bridge’s surprise showed not the screensaver but a man’s face, white-haired with reading glasses perched at the end of his nose, looming over his laptop camera. Devon Chisholme, Senior Executive Officer at the MoD.

‘Is that secure?’ asked Bridge as she sat down.

Giles shrugged. ‘If it isn’t, heads will roll downstairs. Similar to our phone apps, so they tell me.’

‘Feels like half a SCAR meeting. What’s going on?’

On the screen, Chisholme shook his head. ‘Not so much inter-agency intelligence, I’m afraid, as rooting out a bad apple.’ Dunston snorted quietly, but if Chisholme heard it he didn’t react. ‘Put simply, we suspect one of yours is about to sell military secrets to the enemy.’

‘What you neglect to mention,’ said Dunston with an arched eyebrow, ‘is how those secrets came to be in the hands of an SIS officer in the first place.’

‘Yes, yes, we have our own bad apple to deal with as well,’ said Chisholme. ‘But we can handle that internally. What we can’t do is follow your man to Paris and arrest him. Unless you’d prefer we trample all over Emily’s turf and ruin her cosy relationship with the gendarmes?’

Bridge cleared her throat and turned to Giles. ‘Perhaps you’d better start at the beginning.’

‘I should coco,’ Giles muttered, taking the mouse and keyboard. On the screen, Chisholme’s face was replaced with a slide showing the career profile of a nondescript forty-something man, an SIS officer called Simon Kennedy.

Bridge scanned his history. Former signals officer in the British Army, good analyst track record, five months in Ljubljana several years ago before returning to London. ‘Short assignment in Slovenia. What brought him home?’

‘Family,’ Giles replied. ‘His wife became pregnant shortly after arrival, and didn’t want to raise the child there. We had additional concerns, so brought them home and all was well.’

‘Additional concerns?’

‘All in good time. Devon, we can’t see you, but would you care to enlighten Bridge?’

The civil servant sighed. ‘Ms Sharp, do you know what an EMP is?’

‘Electromagnetic pulse,’ she replied, and reeled off what she knew. ‘It knocks out all electronics; networks and computers, obviously, but also alarm clocks, cars, microwaves – anything with a circuit board. Can even wipe hard drives if it’s powerful enough. Two ways to get one: either set off a nuke, or if you’re less keen on mass destruction, rig up a huge generator on wires. But they’re cumbersome and imprecise.’

‘Quite so. Except now, or I should say in the very near future, we will have a third option that fits inside a briefcase, with an area effect of three hundred metres.’

Bridge whistled. ‘That’s a real breakthrough.’

‘Yes it is,’ Chisholme said, ‘so you can understand our dismay when we discovered an MoD researcher appears to have passed the designs to your officer, with intent to sell them to the highest bidder.’

She looked back at Simon Kennedy’s nondescript photo. ‘Old army connection, I assume?’

‘So it seems. And now Kennedy is preparing to make use of another connection.’

On cue, Giles displayed several surveillance photos on the room’s screen. In them Kennedy stood on the banks of a river – the Ljubljanica, Bridge guessed – with another man, making apparently casual conversation that was surely anything but. ‘Boštjan Majer,’ said Giles, expertly pronouncing it bosht-yan my-uh. ‘Information broker and auctioneer of international secrets. He was our additional concern about Kennedy.’

‘The name rings a bell,’ said Bridge. ‘But if you knew Kennedy was friendly with this guy, why did you let him come home?’

‘We only had evidence of this single encounter. Obviously a red flag, but nothing came of it that we could tell, and with Kennedy re-stationed here in London we were able to keep an eye on him. Majer himself has been on UK Borders’ watchlist for years, so we’d know if he tried to enter the country. But he hasn’t, and Kennedy’s been clean as a whistle ever since.’ Before Bridge could say it, he continued, ‘Until now, obviously. The impetus appears to be his impending divorce. Kennedy’s wife is leaving him, taking their child with her and taking him to the cleaners.’

In her mind, Bridge assembled the disparate pieces into a whole. ‘He needs money his wife won’t know about. He remembers a man who’ll pay for secrets, and an old friend who might be able to supply them.’ She turned to Dunston. ‘And now he’s on his way to a rendezvous in Paris. I assume you’ll have Henri Mourad watching?’

Dunston shook her head. ‘Afraid not. Before he came to Paris station, Mourad spent a year working alongside Kennedy on the Balkan desk here in London. He’ll be standing by as backup, but he can’t be the primary shadow, and nobody else I have in the city is up to the job.’

‘Meaning you think I am?’ said Bridge, with half a smile. She and Dunston had crossed swords several times in the past, but the Paris head let this one go with a silent frown.

Bridge matched it. Mourad was the Anglo-Algerian Paris station chief, and a colleague in whom she had complete trust. Not so long ago SIS had maintained officers embedded in cities all over France, any of whom they could have called on. But ever-tightening budgets had cut and cut until those regional officers dwindled to zero.

Being half-French herself, though, this wasn’t the first time Bridge had helped out across the Channel. She contemplated another life in which she’d diverted to Paris, working for Dunston instead of Giles, and suppressed a grimace.

‘What do we know about this upcoming meet?’ she asked as Giles closed the photos and returned Chisholme’s face to the screen.

‘Very little. Majer is on Interpol’s PTS list, and was seen arriving in Paris yesterday.’ Personnes Toujours Surveillées, or People Always Monitored, was a list of individuals in whom Interpol had a perpetual interest, supplied to bureaus and local police around the world. Any reported sighting of someone on PTS was added to their file. ‘Meanwhile we flagged Kennedy buying a Eurostar ticket for Saturday.’

‘In his own name? How did this guy pass training?’

‘No rule against officers travelling to Paris for the weekend. Remember, he doesn’t know we’re watching.’

Bridge turned to Dunston. ‘What’s your instinct? Brush pass along the Seine, or back table at a café?’

‘The possibilities are endless,’ Dunston admitted. ‘That’s why we need an officer on the ground, someone who knows Paris but won’t be recognised, to follow, intervene, and apprehend. I have a friend – in the Police nationale, Devon, not the gendarmerie – ready to assist once you call it in.’

‘But not before you grab them all red-handed,’ emphasised Giles. ‘Obviously we want Kennedy, but we’ve also been trying to bag Majer for years. Two birds with one stone will do very nicely.’

‘I’ll need a firearm,’ said Bridge. ‘Otherwise I won’t be apprehending anyone, let alone keeping them there while les poulets catch up.’

‘Already authorised. You’re booked in with OpPrep tomorrow morning.’

She turned to the screen. ‘Devon, what sort of buyers will Majer approach to sell the designs? Are we talking nation-state resources only, or could you build one of your new EMPs in a shed?’

‘Somewhere in between, I gather. The materials are very expensive, especially the battery formulation, and assembly is tricky. You’d require both funding and specialists.’

‘The sort a terror group might have access to?’

Chisholme didn’t move for five seconds. Bridge couldn’t tell if he was thinking or his screen had frozen. Eventually he said, ‘Let’s try to ensure it doesn’t come to that. Giles knows my feelings on this matter.’

‘Devon wants to arrest Kennedy before he even gets on the train,’ Giles explained. ‘But this is the best chance we’ve ever had to bag Majer, and we’ll still get him before he can sell to Beijing or whomever.’

‘Surely Moscow’s a more likely buyer for this sort of kit?’

Giles looked at Bridge as if she’d suggested he fly a rocket ship to Mars. ‘Ordinarily, yes. But unlikely in this case, given Majer is widely suspected of handling Sasha Petrov’s escape from Russia.’

‘Oh, that’s why his name rang a bell,’ said Bridge, kicking herself for not making the connection. ‘I haven’t thought about Petrov since before Covid.’ Sasha Petrov was Moscow’s very own whistleblower, a Snowden-like infosec staffer who released a trove of classified Kremlin documents into the wild. He’d been headline news for a short time, hunted by Moscow. But Bridge had spent that same time mourning her mother’s sudden death, drinking enough to cope with the loss, and energetically screwing Karl at every opportunity. Current affairs were the last thing on her mind. Then the pandemic had begun, worldwide lockdown followed, and everyone forgot about the embarrassing leak. ‘Wasn’t the Home Office considering his sanctuary claim? He’d be a catch.’

‘Officially they’re still considering it, but that bird has flown,’ said Giles. ‘Too much Russian influence in London these days to rubber-stamp it, and Moscow doesn’t forget. So assume Boštjan Majer remains persona non grata, and he’s more likely to sell to the Chinese.’

Bridge sighed. ‘I’m definitely going to need that gun.’

An officer on the ground, Dunston had said. Bridge’s OIT status – Officer in Theatre, the licence to operate as an SIS field officer – had been a rollercoaster ride. She worked hard to finally obtain it; immediately lost it when her first-ever op went south; spent years trying to get it back; decided she didn’t want it after all; was forced back into it; feared it would be taken away again when she was demoted; and finally received a promotion, instead. It wasn’t so long ago she’d tell anyone who’d listen she was happiest when sat in front of a keyboard, but lockdowns and quarantines had made her restless, even despite her early decision to ‘bubble’ with Karl. They hadn’t been together long, and neither of them was ready to start living together. But the only other option had been to simply stop seeing each other, potentially for a year or more. So they’d alternated between their two flats, mostly using Karl’s because Bridge’s had an uncanny ability to remain messy no matter how many times she tidied it. It had worked out, mostly. They hadn’t tried to stab each other yet, which she considered a success. But the stir-craziness was a constant looming presence, especially for Bridge. Being unable to travel made her understand how much she’d come to expect it as part of being OIT, even if technically it was work.

‘Mesdames et messieurs, bienvenue à Paris Gare du Nord.’

The Eurostar announcement interrupted Bridge’s reverie and returned her to the present. Pretending to focus on her iPhone, she stole a glance at Simon Kennedy. He had no luggage, not even a briefcase.She assumed the stolen plans were on a USB thumb drive, tucked safely in a pocket.

She stayed a good distance behind him as they exited and made their way downstairs to the local trains. Kennedy took a Parisian Navigo card from his pocket and breezed through the turnstile, suggesting he’d been here recently. Perhaps to scout the meeting location? Bridge followed, grateful she wasn’t the only passenger keeping her mask on. Kennedy still wore his, too.

Then they were on a platform, southbound into the heart of the city, where Bridge positioned herself twenty metres from Kennedy outside his peripheral vision. A train arrived, and Kennedy stepped on board. From here it would cross under the Seine to the left bank, past the Sorbonne and south to Saint-Rémy-lès-Chevreuse. Bridge entered the next carriage along and stood by the adjoining window, watching him through the glass.

She checked the map and saw this line connected with the Orlyval, a shuttle to the airport. Bridge wondered if Kennedy had arranged to meet Majer there. Few places were as anonymous as an airport, especially with passenger numbers rising again. If so, Henri would have one hell of a drive on his hands. The Paris chief was waiting in a car above ground, ready to track Bridge’s location when she re-emerged on the street, but that plan assumed the street in question would be within the city. She was glad she’d chosen comfortable boots over fashionable ones, because she might be here for a while.

Loud music suddenly blared from further down the carriage. Bridge turned, expecting to see a busker, but instead she and the other passengers watched a trio of young black men begin to dance as their boom box played an upbeat polka. ‘Mesdames et messieurs, bienvenue à Paris! C’est une belle journée aujourd’hui, nous sommes là pour vous faire sourire!’ they shouted in unison.

It was smooth, co-ordinated, and practised; the lead dancer filmed it all on his phone for TikTok, the second carried the boom box, the third brandished a cup for coins, and none of these duties hindered them as they expertly danced along the carriage and around passengers, perfectly in time to the music. Bridge smiled, preparing to fish out a euro when they drew near, but suddenly they stopped. Another group of young men, four white guys with cropped hair and beards, moved to block their way. One of them shoved the lead dancer back into the others. Another yelled at them to shut the fuck up and get off the train; in fact why not get out of France and go back home? Voices rose across the carriage, some in defence of the dancers and some agreeing with their harrassers. Racist insults followed, and one of the bearded men even shouted ‘Heil Hitler!’ in their faces.

Bridge’s height gave her a stride advantage. She took two quick steps, reached for the sieg-heiling man’s arm and twisted it back behind him, forcing his elbow the wrong way. With her other arm she circled the neck of another beard, pressing hard on his windpipe…

No. She shook her head to clear the image from her imagination and turned away, keeping Kennedy in sight through the window to the next carriage. She couldn’t afford to draw attention to herself or get sidetracked. That her first instinct had been to start breaking bones unsettled her, but regardless, she was working. Much as she didn’t like it, Bridge had to play the part of an ignorant bystander who didn’t want to get involved. She was hardly the only one.

The dancers and racists tumbled out together at Châtelet–Les Halles, still shouting at each other and the surrounding public, while Kennedy remained seated in the other carriage. Bridge wondered again if they were destined for the airport.

But to her surprise Kennedy disembarked soon after, at Port-Royal. She followed him out, maintaining distance as he climbed to street level and turned west along the Boulevard de Montparnasse. Too wide and open for her liking, so she crossed the road and pretended to check her phone before continuing to follow. She didn’t have far to go. After a brief walk, Kennedy buzzed an apartment building door between two small shops. Bridge hung back behind a restaurant truck unloading on her side of the street and watched as he spoke into the grille. The door opened, Kennedy entered, and the door closed again.

Shit. They hadn’t anticipated a private apartment. According to local informants, Boštjan Majer was staying at a hotel off the Champs-Élysées. If he had a bolt hole here on the Boulevard, SIS didn’t know about it.

Or did they? She pulled down her mask, took out her phone, and called Giles. He answered on the second ring. ‘Line?’

‘Secure. Kennedy’s entered an apartment. I can’t tell which one, but can you run the building for me?’ She relayed the address and waited, leaning against a lamppost outside the restaurant and adopting the look of a bored local. She heard the tell-tale click of a third line connecting.

‘Bridge, this is Emily Dunston. That building is home to a safe harbour, but it hasn’t been used for months.’

She swore. Safe harbour was the code name for a network of apartments in major cities, owned by SIS – or rather by anonymous shell companies in the Caymans financed by SIS’ shadow fund – and available for any officer in need. Worried about being lifted by the enemy? Head for the local safe harbour. Passing through, but overnighting at a hotel isn’t safe? Stay at a safe harbour. Need to arrange a clandestine meeting somewhere you can guarantee isn’t bugged? Use a safe harbour.

The apartments were managed by local caretakers, normally senior officers approaching retirement. It was a quiet appointment, no footwork required, no diplomatic declaration necessary. While the caretakers were employed by SIS, they weren’t conducting operations or following mission orders. All they had to do was clean the apartments, regularly sweep them for surveillance devices, and be on call 24/7 at an emergency number.

‘Can’t be a coincidence that this is one of ours, can it?’ Bridge said. ‘Where’s Henri?’

At the mention of his name, the Paris chief cut in to the conversation. ‘On my way; fifteen minutes max.’

‘That apartment isn’t booked today or any time in the future,’ said Dunston. ‘And Farrow, the caretaker, is a Cold War relic. Stickler for procedure.’

Giles mused, ‘Which means either Kennedy is breaking into the apartment…’

‘Or Farrow is compromised,’ said Bridge, completing the thought. ‘Maybe he was offered a cut. Give his pension a boost.’

‘The apartment number is 4C,’ said Dunston. ‘How do you want to play this?’ One thing Bridge liked about the Paris head – perhaps the only thing, if she was honest – was Dunston’s willingness to trust the judgement of whoever was on the ground, rather than micro-managing from behind a desk. Bridge ran through the potential scenarios in her head, and they were all bad. The street was growing busy as lunchtime approached, and in the few minutes she’d been on the phone several people had already left or entered the apartment building.

‘Can you send me a file pic of Farrow?’

‘Of course. Give me a moment.’

‘In the meantime, I’d say don’t contact him or local police yet. If the caretaker’s in on it and sees you call out of the blue, or if one of them is scanning police radio and hears the call, they’ll abort. I can’t cover front and back door by myself, but the one thing we have on our side is the element of surprise. Blow that, and Kennedy and Majer will evacuate – assuming Majer’s even here, yet – while Farrow will say he’s just cleaning the place, and we’ll have nothing.’

Her phone vibrated as Farrow’s file photo landed in her inbox. He looked like a hundred other senior SIS officers; slim, around sixty, thinning white hair. She didn’t think she’d seen him exit the building while she was watching, but given his everyman look and the prevalence of masks, she couldn’t be sure.

‘Photo received. Henri?’

‘Still ten minutes out,’ he said.

Bridge weighed her options. If Majer wasn’t already in the apartment, she could secure Kennedy and Farrow in the meantime and wait for him. But if he was there, how long before he left again? ‘Every minute I wait increases the risk we lose them altogether. I’m going to blag my way into the building.’

‘No blag necessary,’ said Dunston. ‘That building has keypad entry, I can give you the code. You’re on your own getting into the apartment, though.’

Bridge was already crossing the road, pressing a single AirPod into her ear and pulling her mask back up. When the earpiece beeped to confirm its connection she said, ‘I’ll rely on my winning personality. And I’ll leave this line open, so I won’t have to reconnect to call you for that police backup. I don’t fancy fiddling about with my phone while trying to watch three targets.’

‘Understood,’ said Giles. ‘We’ll mute until you give the word.’

‘Meanwhile I’ll call my police contact and tell him to stand by, but no movement or radio for now,’ said Dunston. ‘Ready for that code?’

Bridge was. She tapped it into the building’s keypad, pulled open the buzzing door, and slipped inside. OpPrep had issued her with a subcompact Glock 26, small enough to be unobtrusive in a shoulder holster under her jacket. She’d had to wait for thirty minutes in a private room at St Pancras while security checked her special dispensation to carry a firearm on Eurostar, but she was glad of it now as she climbed the stairs. There was a good chance nobody else would be armed; information brokers worked on trust, and an experienced operator like Majer might not even need backup muscle. Belatedly, she wondered how Kennedy was planning to receive the money. Could he have opened a Swiss account? Surely he wouldn’t ask Majer to transfer a few hundred grand to his local branch of Barclays.

The building was more spacious than it looked from outside, with half a dozen apartments on each floor. She passed several people on the stairs; they were all masked, but none resembled Kennedy or Majer and the building had no elevator. Finally she reached the fourth floor, quiet except for the tinny din of daytime television coming from 4A to her left. She turned, following the doors round to the unremarkable and unobtrusive 4C. That being rather the point.

Now she was faced with getting into the apartment, and even as she stood there figuring out her next move, Bridge heard someone in the stairwell pass this floor on the way to the fifth. The door lock was a regular Yale, which she could pick inside ninety seconds, but that was more than enough time for someone to pass on the stairs and raise the alarm. She also couldn’t hear any noises from inside the apartment, and while lock-picking was quiet, it wasn’t silent. Anyone inside might hear it.

On the other hand, if she knocked and someone called out from behind the closed door, what could she say? ‘Livraison spéciale’ wouldn’t cut it; nobody using a safe harbour apartment would order any kind of delivery, special or otherwise. They’d immediately be suspicious.

Then again, she did have a gun.

Bridge drew the pistol, held it inside her jacket pocket, then bent her knees to make herself look shorter through the peephole. None of the men inside that apartment would recognise her, face mask or not. She knocked on the door with her free hand and waited, deciding to pose as the daughter of a concerned neighbour. Farrow wouldn’t have needed to visit much during the pandemic, so the neighbours might not have seen him for months. Long enough to grow worried about an older man who seemingly lived alone.

But nobody called out from inside the apartment, or came to the door. Even over the other flat’s television monotone Bridge expected to hear voices, footsteps, scraped chair legs, something from inside 4C to indicate movement. Had Dunston given her the wrong apartment number? Impossible. The Paris head didn’t make that kind of mistake. But Bridge had now been standing here, a highly visible stranger in the building, for too long. Only one option remained.

Like all SIS officers, Bridge had trained for field work at The Loch: an MoD facility in the Scottish highlands where Sgt Major Instructor ‘Hard Man’ Hardiman and other specialist tutors trained everyone from civil servants to security staff in dangerous work. It was where she’d learned to pick locks, fight in close quarters, and fire the gun she now gripped in her pocket, loose but ready as she’d been taught. She’d also been taught that firing a handgun at a lock was more likely to ricochet and kill the shooter than open the door, as even a basic lock was built from hardened solid metal.

The wooden frame around the lock, though, was a different matter.

‘No answer, no indication of movement,’ she whispered into her earpiece. ‘Prepare for breach.’

Bridge stood back from the door, sighted the jamb above the lock, and slowed her breathing. She fired one shot – immediately re-sighted, now aiming directly below the lock – second shot, and now she was moving, twisting into a side kick that forced the lock bolt through the now-splintered wood and onward, slamming the door against the apartment’s side wall as she reset into a ready crouch. She raised the Glock from her low position, covering anyone who stood in the hallway.

But nobody did. Bridge waited three seconds, still hearing no sound or movement. Were they waiting for her, hoping she’d walk into a crossfire? Possible, and now unavoidable. The door was breached; there was no going back.

She stood up and inched forward into the hallway, pushing the door closed behind her. Even the television-watcher in 4A must have heard the shots. They might be calling the police right now, but Bridge couldn’t let the thought distract her. Her more immediate concern was not getting shot in the next five seconds.

Still no sound as she reached the sitting room door and stopped, her back against the wall. She crouched again, hoping anyone shooting was inexperienced enough to instinctively aim high. Most people did. Something solid pressed into her back, and she turned to find a scented air freshener plugged into an outlet. She pulled it out and flung it ahead of her into the room, to draw their fire.

As it hit the back wall and clattered to the floor Bridge swung around the door frame, position low and pistol up, seeking targets.

There were none. At least, none standing upright.

Three men lay on the floor, silent and bloody. Two held guns. None moved, not even the rise and fall of shallow breath. Bridge swept the rest of the apartment, confirming it was empty. She holstered the Glock and returned to the sitting room. Then she pulled down her mask, and regretted it when stale iron and body odour washed over her, clinging to the back of her throat.

‘Bridge, abort!’ Giles suddenly shouted in her ear. ‘Get out, now.’

Caught by surprise, she reeled in confusion. ‘Nearly gave me a bloody cardiac. You were supposed to be on mute. What’s going on?’

‘Word from my police contact,’ said Dunston. ‘Someone heard shots, and an armed response unit is en route.’

‘Fuck.’ The neighbour must have called them. ‘Tell Henri to stay back. How long have I got?’

‘Police ETA unknown, but imminent. Mourad is holding his position, five minutes away on Rue Guynemer. What’s the situation?’

‘Total clusterfuck. Three dead.’ Bridge stepped around the bodies, careful not to touch anything or step in blood. Kennedy was nearest the door, face down with a small Browning pistol in one hand, his shirt soaked in blood from a chest wound. Majer sat across the room, slumped on the floor with his back against an easy chair, wielding a Heckler & Koch pistol. His chin rested on his chest as if asleep, but the wreckage of his own chest said otherwise. The final body was an older man, hair as grey and thin as his clothes, matching the photo of Farrow. He lay on his bloody front, face turned to the side, hands empty of weapons but reaching out for rescue and salvation. ‘Kennedy, Majer, and Farrow are all off the board. Looks like a double-cross of some kind…’

‘Move now, think later,’ Giles urged her.

‘Hang on, hang on,’ said Bridge, looking around the room. Bloody smears and handprints stained the furniture and walls, suggesting some or all of these men had been given time to take final breaths, heavy gasps of desperation and regret. Who shot first? Who wouldn’t back down? Who attempted the double-cross in the first place? Those questions might never be answered, but she could still salvage something from this carnage. ‘If they all shot one another, then the plans are still here.’

‘To hell with the plans, just get out,’ said Dunston, but Bridge was already crouching by Kennedy, turning his body over.

She pulled his jacket open, ignoring the blood-soaked cloth slipping between her fingers. His inside left pocket contained his passport and a Samsung phone. She pocketed the latter, hoping her CTA colleagues back in London could crack it open, then turned to the other side. It held a thin credit card wallet and Navigo card. She was about to look in the outside pockets when she noticed a narrow opening halfway down his inside left pocket lining. A spectacles pouch, complete with thin zip enclosure. Bridge gripped the bloody material and pulled at the zip.

‘Et voilà,’ she murmured as a USB thumb drive slid out onto Kennedy’s chest. Hearing distant shouts from the apartment stairwell, she pocketed it and turned to leave. There would be one hell of a mess to clean up – not just the physical scene, but the political ramifications and explanations the Service would have to provide, both private and public. But SIS was well-practised at concocting vaguely reassuring official explanations to spare families, and the public, from the sordid truth. No doubt Giles was already working that angle back in London.

All she had to do was go up a floor and wait out the cops. There might even be a fire escape down from the rooftop.

She made it to the hallway before three Police nationale officers stormed in, guns raised, screaming at her to drop to her knees with her bloody hands in the air.

4

‘Holy shit. Casey, you seen this?’

Casey Lachlan didn’t hear. He was wearing earmuffs, focused down range, the stock of his Colt MT6601 nestled into his shoulder, and head cocked to sight along the barrel. No mount or scope, no bench support to steady the rifle. ‘Shooting clean,’ his father had called it, ever since he first took young Casey to a range. Of course, that was with the old man’s hunting rifle, an M1, which was never designed to take scopes unless you were a sniper anyway. Over the years ‘shooting clean’ had come to be a sort of family catchphrase for doing a job right, without fuss.

Casey wished he was here now. Maybe he was watching somehow. Casey eased out the tension in his shoulders to focus on the target. He inhaled deep, exhaled steady, squeezed the trigger. The crack of a single shot, still loud through the earmuffs, and a split-second muzzle flash. Letting his shoulder move with the stock as it bucked in recoil. He remembered the first shot he ever made, how stiff he’d been, trying to prove the recoil was nothing. All it bought him was a shake of his father’s head and three days of aching shoulder.

Today, by the time his shoulder even moved, the bullet was a hundred yards down range and buried in the target. At least, he hoped that’s where it landed. He placed the rifle safely on the bench in front of him, slipped off the earmuffs, and picked up his binoculars to check.

‘How’s it?’ asked Mike, now standing next to him.

Casey passed him the binoculars. ‘Inch left of centre. Not bad for first shot of the day.’ He said that last part a little louder, so anyone nearby would hear. But when he glanced around to see who that might be, nobody was close enough. Freedom Hills Range was a no-frills kind of place, nestled in a shallow valley. The owner supplied the space, the targets, a bathroom, and refreshments. You wanted anything else, you brought your own – including beer and chairs, which was why the other early risers were still tailgating at their trucks instead of over here shooting.

‘Get a bench support and you’d have been dead on,’ said Mike. Before Casey could reply he handed back the binoculars and said, ‘I know, I know. Shooting clean, all that bullshit. Me, I prefer being accurate.’

Casey smiled. ‘I like both,’ he said, putting the earmuffs back on to signal the conversation was over. Mike Alessi was a year older than Casey, a nerd who’d forgotten more about computers than Casey would ever know. But, useful though he sometimes was, the Flag Born wasn’t about computers. It was about defending America, and that took marksmanship. Casey had him licked but good in that area. As he reached for the rifle again, though, Mike held out his iPhone to show Casey something.

‘Wait, you gotta see this,’ he said. Then, realising the screen was blank: ‘Shit, hold on. Trust me, it’s worth it. You need to listen, too.’ Casey removed his earmuffs again while Mike unlocked the phone. The screen lit up on a page at Frank, the patriotic version of YouTube, ready to play a video. The preview image showed the former president, looking serious and committed as always, facing the camera in a darkened room. Old Glory hung behind him, its stars and stripes artfully draped. Mike tapped the screen, and the video played.

‘My fellow patriots. You true and loyal Americans. Everybody knows this is a dark time, a terrible time. It’s a crisis, what the liberals are doing to our country. Right now, in cesspools like San Francisco and Los Angeles, they’re paying black women to have babies. Can you believe it? Those of us who understand, we can see this for what it is – white genocide in action, right? The great replacement. And it’s not only happening here in our great country. This is all over the world, our beautiful heritage, being destroyed and wiped out by people who want the white race to disappear. One day we’ll all be gone if they have their way, believe me.’ His voice rose. ‘But true patriots will not stand for it. And now we have a chance, a perfect chance, to show the world that we will not lie down and let our culture be destroyed. We will not abandon our people to the liberal nightmare!’

Casey glanced at Mike. ‘Is this a campaign?’ Mike waved shush and pointed at the video.

‘You know I can’t go on TV and tell you this. They don’t want you to hear the truth, not even our so-called allies. This country is so bad, I have to deny my own words if they call me out. And if you try to do anything about it, the fake news media will call you traitors and other bad things, instead of the heroes you are. But like I said, this is happening all around the world.’ He smiled sadly. ‘And some places, well, the liberals aren’t so much in control. I hear from leaders in Europe every day, they call me and say, “Mr President,” because they respect me, “Mr President, we need your help. The EU, full of terrible people, they won’t do anything. We’ve got immigrants flooding our borders every day, thousands of them, they walk in and take over. We can’t build a wall, the EU won’t let us, and our own people aren’t trained for this. We need strong, loyal American patriots to come and help us deal with this invasion. Please send your best men.” They’re crying, these big, strong men, leaders who never cry, but they’re so grateful for everything we’ve done, and everything we can still do. The media is watching, so I can’t say any more, but I want all of you, loyal warriors, to think about how you can help our brothers in the old fatherlands. The time for Operation Patrios is coming soon. Watch for the signal. God bless me, and God bless us all.’

The video ended. Realising he’d been holding his breath, Casey covered it up by spitting on the ground. ‘Fucking EU. Dumb liberal motherfuckers are helping the enemy wipe them out, and they don’t even know it.’

Mike smiled. ‘So you think it’s real?’

‘Was there a word of a lie in what he said?’

‘I guess not, but they can do a lot with computers these days.’

Casey shook his head. ‘They can’t fake that, Mike. I didn’t see any cuts, did you? Besides, why would the president post fake news of himself?’

‘He didn’t post it. It was, hold on…’ he tapped on his phone screen. ‘Patriotic And True Rebels In Our Service. It’s the first video they’ve ever posted.’ He showed the screen to Casey, who read the user name, then laughed.

‘P-A-T-R-I-O-S,’ he said, pointing at the user name’s initials. ‘That’s what he called the operation, right?’

Mike’s eyes widened like Casey had shown him the hidden arrow in the FedEx logo. ‘That’s right! Holy shit, you got marksman’s eyes all right.’

The range was quiet, as it often was early on a Saturday. Only a dozen other people hanging out, and none of them close enough to have heard what they were talking about. Casey said, ‘Who else has seen this?’

‘Everyone,’ Mike laughed. ‘It’s viral, man. A guy linked to it on the Eagles & Aviators board last night, but it was already spreading. By now the whole world’s seen it.’

Casey grunted and prepared to resume shooting. ‘Then I guess those guys in Europe are gonna have plenty of help coming their way.’

‘But not everyone got sent a bunch of money.’

That got his attention, as Mike must have known it would. Casey paused mid-grab for his rifle. ‘What money?’

‘It was wired to the Flag Born account this morning, from the same people. Look.’ Mike launched his bank’s app and showed him a transfer to their militia’s fund that morning: thirty thousand dollars, from an account labelled simply PATRIOS.

Casey whistled. ‘Who are these guys?’

‘I don’t know, but not everyone got money like this. One board went to hell this morning when a couple groups who’d been paid asked about it, ’cos they assumed everyone else did too. But most guys didn’t get anything, and they’re pissed. There’s like a thousand replies already.’

‘Did you tell them we got paid?’

‘Hell, no. Not when I realised they were picking and choosing.’ Mike looked offended. ‘I’m not stupid.’

‘You tell any of our guys about it yet?’

‘About what?’ A voice spoke behind Casey, startling him. He turned to see Brian, the Flag Born leader, walking up.

‘Oh, hey, Brian,’ said Mike. ‘We were just talking—’

‘About the president’s video,’ Casey interrupted quickly, before Mike could open his big mouth. ‘You seen it?’

Brian nodded. ‘Damn straight. That man’s got a way with words, ain’t he? Can’t say I agree with him this time, though.’

‘Don’t agree? Every word he said was true.’

‘Damn straight, but it ain’t our fight. Not our business to get involved in other countries’ business, right? They got a problem with towelheads, it’s up to them to figure out the answer. Hell, it don’t take a genius.’ He pointed a finger down range and mimed firing a pistol.

‘That’s exactly why we should go over there and help them,’ said Casey. His opinion of Brian’s ‘leadership’ was no secret. If he could be bothered he’d have staged some kind of coup by now to take over – he was sure the others would support him, if he did – but it seemed like a lot of work, and he did what he wanted anyway.

Brian shook his head. ‘Uh-uh. Don’t you think we’ve got enough problems of our own right here in America? Sun Tzu said, “Only an idiot fights a war on two fronts.” Let’s fix our own problems before we start helping others. America first.’ He turned and left.

Mike looked like he was trying not to laugh. ‘What’s funny?’ asked Casey.

‘That quote wasn’t… never mind.’ Mike shook his head. He watched Brian walk back to the tailgate gathering. ‘No European vacation for us, I guess.’

‘Bullshit. None of those guys know about the money, right?’

‘No, but Brian said—’

Casey almost vibrated with anger. ‘Screw what Brian said. What else is the Flag Born for, if not to preserve the white man’s heritage and integrity? We’re a global brotherhood, and I got plenty of vacation due. How about you?’

‘How long for? There’s no instructions or nothing.’

‘Not yet, but I bet you can figure out how to contact someone with that internet brain of yours. Must be somebody’s job to tell us where to assemble once we get there, right?’

Mike looked at his phone, as if the answers might flash up on-screen. ‘Thirty grand… I mean, that’s enough to fly a dozen of us there and back, easy.’

Casey followed Mike’s gaze to the other members, but shook his head. ‘Sure,’ he said slowly, ‘if all we need to do is fly there and back. But think about it. We’ll have to rent a car. Sleep somewhere. Eat, drink. Europe ain’t cheap, Mike.’ Casey had been to Dublin five years ago, on vacation, making him the voice of authority on all things European. ‘Besides, be honest. How many of those guys do you think got the balls?’

Truth was, Casey wasn’t a hundred per cent sure he had the balls himself, but he was damned if he’d let Mike see that. And what he’d said was true; the Flag Born had been formed for exactly this purpose, waiting for a call like this. He’d spent months telling anyone who’d listen that the way to solve Europe’s problems was to go in there, Iraq-style, and lead their brothers into battle against the encroaching immigrants. Casey had passed up protesting at the Capitol because he wanted to take action, not freeze his ass off carrying a home-made sign. By the time he saw shit was going down there for real, it was too late. But now their American president – the real president – had given them a mission, and Europe was finally ready for them. Patriots didn’t shirk from their duty.

Especially if it meant reminding the lower races who was in charge.

‘You and me, man,’ he said. ‘We can be goddamn heroes. Get online and ask for details. Tell whoever’s co-ordinating from Europe that we’re standing by and ready to fly.’

Casey put on his earmuffs, picked up his Colt, and fired three quick shots without resetting. Checking through the binoculars, he could almost feel the old man’s hand on his shoulder, nodding in approval at the tight triangle of holes.

5

Bridge was used to being arrested.

The first time had been when she was fifteen, after she hacked the local council’s website and defaced it with vegetarian animal rights propaganda. Her mother was mortified at the scandal of a police car outside their house, while Bridge was merely angry at whichever of her so-called friends ratted her out. There had been a couple more times as a teenager, and the University hack at Cambridge that led to her being recruited for SIS. Since taking on field work, though, she’d come to know the inside of cells and interrogation rooms in a surprising variety of countries, and the most fascinating thing about them was how stubbornly un-fascinating they all were.

Paris was no exception. They’d taken everything from her pockets, including the USB drive, then thrown her in a cell three metres square with a poured concrete floor, old plaster walls, a moulded concrete bench, and a small high window covered by steel mesh. They left her to stew there before dragging her to the interrogation room which, like the cell, could have been anywhere in the world. Another concrete floor, plain walls, table bolted to the floor with fixing points for shackles, uncomfortable wooden chairs, and the ubiquitous recording devices; cameras high in every corner with red activation lights blinking passively, and a regulation audio recorder on a wall-mounted shelf.

‘At least the cell had a window,’ she said to the officer as he gently but firmly pressed her into one of the chairs. He rolled his eyes and moved back to the door, watching her.