5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

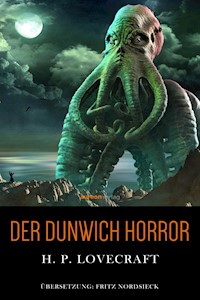

- Herausgeber: The Dunwich Examiner

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Dunwich, Massachusetts, is a place the maps remember but the outside world prefers not to. Its collapsing farmsteads and weather-beaten churches cling to the hills while something far older presses against the thin skin of reality.

On the remote Whateley farm, Old Wizard Whateley and his daughter Lavinia strike a bargain with forces better left unmentioned. One child is born already wrong, racing through childhood with unnatural speed. Another is born unseen, a presence that swells the house, shakes the hills, and leaves great circular tracks in the fields. As cattle are drained, stones are scorched, and ritual chants rise from Sentinel Hill, Dunwich begins to understand that a door has been opened which cannot easily be closed.

When the invisible horror finally tears loose from its restraints, the hills boom with an inhuman cry. It will take the combined efforts of Miskatonic scholars, frightened villagers, and desperate clergy to trace the creature's path and confront the blasphemy at its core.

The Dunwich Horror remains one of H. P. Lovecraft's most influential tales of rural occultism and cosmic intrusion. This Barrow Street Edition presents a clean, carefully prepared text optimized for modern print and digital reading, preserving Lovecraft's language while eliminating the typographic noise of early twentieth-century typesetting and later digital scans.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

TheDunwichHorroris in the public domain. All original additions, including illustrations, summaries, and annotations, are copyright © 2025 by Emory Holt and published as part of The Barrow Street Edition under The Dunwich Examiner™, an imprint of Client Informatics, LLC.

No portion of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law.

Use of this work for the purpose of training artificial intelligence models, including large language models or generative AI systems, is expressly prohibited without the publisher’s prior written consent.

Published by The Dunwich Examiner™, an imprint of Client Informatics, LLC.

The Barrow Street Edition — restored and annotated by Emory Holt.

Book Cover and Illustrations by The Dunwich Examiner™

ISBN: 978-1-970826-04-3

For more information, visit us at: https://dunwichexaminer.com/literary-inquiry

Contents

"They do not rise from the earth, but through it—for the hills are not hills, but lids."—Fragment found in the margin ofThe Reverend Hoadley’s Missing Sermon, 1747

Introduction

Ithasbecomenecessary, for the benefit of those studying the recovered tales of our region, to address the origins and nature of the document called The Dunwich Horror. Though printed publicly in 1929 beneath the byline of H. P. Lovecraft of Providence, those of us familiar with the deeper archives of Arkham and Dunwich recognize its striking resemblance to certain suppressed accounts, its peculiar alignment with events long obscured from public record.

The nearness of this publication to our present moment creates a peculiar unease. I hold in my hands pages written not by some ancestral voice but by a man whose correspondence still arrives in Arkham, whose name appears in the visitor logs of libraries where I myself have worked. This temporal proximity renders the customary tools of literary analysis insufficient. We lack the safe distance that transforms testimony into text.

Lovecraft's version appears to draw from fragments circulated among certain Miskatonic correspondents after the Sentinel Hill Affair of 1928. The resulting story retains details that seem too precise for invention, allowing certain obscured truths to slip quietly into the bloodstream of literature.

The hills and river-vales described correspond to actual geography. The "Aylesbury Pike," the "Miskatonic's upper reaches," and the "decaying farms of Dunwich" align with regions surveyed by the Arkham Geological Society before their charter was dissolved. Lovecraft, who visited western Massachusetts under literary pretense, absorbed enough of this atmosphere to write a story that reads less like creation than transcription.

I have walked these same paths more recently. What strikes me is not the accuracy of physical description but the weight of absence that hangs over these places. They are marked by what is no longer there, by the curious reluctance of vegetation to reclaim certain clearings. When local residents speak of these locations, they often look beyond the listener, addressing themselves to the air.

Within the hidden canon of the Mythos, The Dunwich Horror holds particular significance for its treatment of the entity called Yog-Sothoth, the key, the gate, and the guardian of the gate. The Whateley family's corruption and the monstrous birth at Sentinel Hill suggest attempts to manifest something beyond ordinary comprehension. Here lies the unsettling suggestion that knowledge itself might become a sacrament, and thought a portal. The invisible twin that devastated Dunwich seems neither wholly of this world nor entirely separate from it, aligning with certain Arkham physicists' theories of dimensional overlap, perceptible only through vibration or scent.

Such technical explanations offer the comfort of classification, suggesting the phenomenon remains susceptible to analysis. Yet I have spoken with those who knew the surviving witnesses. Their accounts suggest a more unsettling possibility, language fails not because the observers lacked vocabulary but because human perception itself reached its boundary. What entered Dunwich may have belonged to an order of reality for which we possess no grammar.

Students of The Dunwich Examiner will recognize The Dunwich Horror as a central text in what some scholars term the Miskatonic Cycle, that body of reports encompassing The Call of Cthulhu, The Shadow over Innsmouth, and The Whisperer in Darkness. In those other testimonies the Old Ones act unseen, their motives obscure, but in Dunwich, for one breathless season, the veil appears to have thinned. It is also one of the rare occasions in which humanity seemed to prevail. Dr. Henry Armitage and his colleagues, by reciting the formula of dismissal, forced the aberration to dissolve back into the geometries from which it had been summoned. Yet papers attributed to Armitage, those withheld from the University archives, suggest he never believed the thing was banished entire. "The gate," he wrote, "once opened, remembers the hand that touched it."

I admit a particular sensitivity to these materials. The papers I have accessed were not simply discovered but actively sought. Certain questions linger for which I have no satisfactory answer. Why were these documents released when so many others remain sealed? What calculations determined that this particular account could be shared while others could not? The archive is not a neutral repository but a curated silence, and I work within its constraints.

Thus The Dunwich Horror endures not as a tale of rural witchcraft but as a threshold text. The same forces that stirred beneath Sentinel Hill are rumored to vibrate under the stones of Kingsport, Innsmouth, and Arkham itself. The story's closing reassurance, "The thing has gone forever," reads as wishful thinking upon a page that still hums faintly when brought near certain instruments.

Those who study these matters should proceed with care. Each hill, each ruin, each half-forgotten ritual joins a larger pattern whose contours are not of our drawing. Lovecraft recorded only what glimpses reached him. The rest remains obscured, though the earth, I fear, is less forgetful than men.

Whippoorwills and Stone Lids

Whenatravelerin north central Massachusetts takes the wrong fork at the junction of the Aylesbury pike just beyond Dean's Corners he comes upon a lonely and curious country. The ground gets higher, and the brier-bordered stone walls press closer and closer against the ruts of the dusty, curving road. The trees of the frequent forest belts seem too large, and the wild weeds, brambles, and grasses attain a luxuriance not often found in settled regions. At the same time the planted fields appear singularly few and barren; while the sparsely scattered houses wear a surprising uniform aspect of age, squalor, and dilapidation. Without knowing why, one hesitates to ask directions from the gnarled, solitary figures spied now and then on crumbling doorsteps or in the sloping, rock-strewn meadows. Those figures are so silent and furtive that one feels somehow confronted by forbidden things, with which it would be better to have nothing to do. When a rise in the road brings the mountains in view above the deep woods, the feeling of strange uneasiness is increased. The summits are too rounded and symmetrical to give a sense of comfort and naturalness, and sometimes the sky silhouettes with especial clearness the queer circles of tall stone pillars with which most of them are crowned.

Gorges and ravines of problematical depth intersect the way, and the crude wooden bridges always seem of dubious safety. When the road dips again there are stretches of marshland that one instinctively dislikes, and indeed almost fears at evening when unseen whippoorwills chatter and the fireflies come out in abnormal profusion to dance to the raucous, creepily insistent rhythms of stridently piping bullfrogs. The thin, shining line of the Miskatonic's upper reaches has an oddly serpent like suggestion as it winds close to the feet of the domed hills among which it rises.

As the hills draw nearer, one heeds their wooded sides more than their stone-crowned tops. Those sides loom up so darkly and precipitously that one wishes they would keep their distance, but there is no road by which to escape them. Across a covered bridge one sees a small village huddled between the stream and the vertical slope of Round Mountain, and wonders at the cluster of rotting gambrel roofs bespeaking an earlier architectural period than that of the neighboring region. It is not reassuring to see, on a closer glance, that most of the houses are deserted and falling to ruin, and that the broken-steepled church now harbors the one slovenly mercantile establishment of the hamlet. One dreads to trust the tenebrous tunnel of the bridge, yet there is no way to avoid it. Once across, it is hard to prevent the impression of a faint, malign odor about the village street, as of the massed mold and decay of centuries. It is always a relief to get clear of the place, and to follow the narrow road around the base of the hills and across the level country beyond till it rejoins the Aylesbury pike. Afterward one sometimes learns that one has been through Dunwich.

Outsiders visit Dunwich as seldom as possible, and since a certain season of horror all the signboards pointing toward it have been taken down. The scenery, judged by any ordinary esthetic canon, is more than commonly beautiful; yet there is no influx of artists or summer tourists. Two centuries ago, when talk of witch-blood, Satan-worship, and strange forest presences was not laughed at, it was the custom to give reasons for avoiding the locality. In our sensible age--since the Dunwich horror of 1928 was hushed up by those who had the town's and the world's welfare at heart--people shun it without knowing exactly why. Perhaps one reason--though it can not apply to uninformed strangers--is that the natives are now repellently decadent, having gone far along that path of retrogression so common in many New England backwaters. They have come to form a race by themselves, with the well-defined mental and physical stigmata of degeneracy and inbreeding. The average of their intelligence is woefully low, whilst their annals reek of overt viciousness and of half-hidden murders, incests, and deeds of almost unnamable violence and perversity. The old gentry, representing the two or three armigerous families which came from Salem in 1692, have kept somewhat above the general level of decay; though many branches are sunk into the sordid populace so deeply that only their names remain as a key to the origin they disgrace. Some of the Whateley's and Bishop's still send their eldest sons to Harvard and Miskatonic, though those sons seldom return to the moldering gambrel roofs under which they and their ancestors were born.

No one, even those who have the facts concerning the recent horror, can say just what is the matter with Dunwich; though old legends speak of unhallowed rites and conclaves of the Indians, amidst which they called forbidden shapes of shadow out of the great rounded hills, and made wild orgiastic prayers that were answered by loud crackings and rumblings from the ground below. In 1747 the Reverend Abijah Hoadley, newly come to the Congregational Church at Dunwich Village, preached a memorable sermon on the close presence of Satan and his imps, in which he said: It must be allow'd that these Blasphemies of an infernal Train of Demons are Matters of too common Knowledge to be deny'd; the cursed Voices of Azazel and Buzrael, of Beelzebub and Belial, being heard from under Ground by above a Score of credible Witnesses now living. I myself did not more than a Fortnight ago catch a very plain Discourse of evil Powers in the Hill behind my House; wherein there were a Rattling and Rolling, Groaning, Screeching, and Hissing, such as no Things of this Earth cou'd raise up, and which must needs have come from those Caves that only black Magic can discover, and only the Divell unlock.

Mr. Hoadley disappeared soon after delivering this sermon; but the text, printed in Springfield, is still extant. Noises in the hills continued to be reported from year to year, and still form a puzzle to geologists and physiographers.

Other traditions tell of foul odors near the hill-crowning circles of stone pillars, and of rushing airy presences to be heard faintly at certain hours from stated points at the bottom of the great ravines; while still others try to explain the Devil's Hop Yard--a bleak, blasted hillside where no tree, shrub, or grass-blade will grow. Then, too, the natives are mortally afraid of the numerous whippoorwills which grow vocal on warm nights. It is vowed that the birds are psychopomps lying in wait for the souls of the dying, and that they time their eerie cries in unison with the sufferer's struggling breath. If they can catch the fleeing soul when it leaves the body, they instantly flutter away chittering in demoniac laughter; but if they fail, they subside gradually into a disappointed silence.

These tales, of course, are obsolete and ridiculous; because they come down from very old times. Dunwich is indeed ridiculously old--older by far than any of the communities within thirty miles of it. South of the village one may still spy the cellar walls and chimney of the ancient Bishop house, which was built before 1700; whilst the ruins of the mill at the falls, built in 1806, form the most modern piece of architecture to be seen. Industry did not flourish here, and the Nineteenth Century factory movement proved short-lived. Oldest of all are the great rings of rough-hewn stone columns on the hilltops, but these are more generally attributed to the Indians than to the settlers. Deposits of skulls and bones, found within these circles and around the sizable table-like rock on Sentinel Hill, sustain the popular belief that such spots were once the burial-places of the Pocumtucks; even though many ethnologists, disregarding the absurd improbability of such a theory, persist in believing the remains Caucasian.

Chapter Reflection

The Discipline of Attention

Dunwich does not introduce itself with names so much as with distances. The traveler who takes the wrong fork at the Aylesbury pike discovers that what lies ahead is less a town than a thinning of the civilized world. The hedgerows lean inward, the soil grows stingier, and the houses rot into their own shadows, until it seems the landscape itself resists both notice and memory. Long before any talk of Whateleys or rituals, the story establishes a more unsettling fact, this is a geography that has fallen into institutional forgetting, beyond the reach of maps, census-takers, and historical records.

Reading Lovecraft's opening chapter now, years after the events it portends, one notices that nearly all of it is description. This is not wasted scenery but necessary groundwork. The text arranges hills, ravines, stone circles, and marshes with uncommon precision, as though mapping coordinates rather than setting a mood. Sentinel Hill, with its ring of rough-hewn stone pillars and its altar-rock, is introduced as a physical feature, but every detail, the symmetrical, "too rounded" summits, the strange skull deposits around the stones, the "Devil's Hop Yard" where nothing grows, serves a narrative purpose beyond mere atmosphere. The text lingers on these topographical features, training our attention to notice what might otherwise seem incidental. This descriptive intensity creates a visual inventory that will prove essential when later scenes must rely on partial glimpses rather than full disclosure.

What becomes apparent through re-reading is how thoroughly this institutional forgetting has been established and maintained. Dunwich exists as a blind spot within systems of knowledge that should catalog and preserve it. The town appears on no tourist maps despite scenery "more than commonly beautiful." Academic inquiry avoids it despite its evident anthropological interest. Even neighboring communities participate in this collective amnesia, "since a certain season of horror all the signboards pointing toward it have been taken down." This erasure is not merely neglect but active omission, a deliberate turning away that extends beyond casual disinterest into something more structured and pervasive.

The universities that might study Dunwich's stone circles classify them dismissively as "Indian" rather than conducting proper archaeological inquiry. The neighboring towns remove signage rather than addressing whatever troubles the region. The local government seems absent entirely. Whether by design or instinct, this institutional blind spot creates precisely the conditions necessary for certain phenomena to persist undocumented and uncontrolled. The forgetting functions not as failure but as facilitator, benefiting both those who wish to avoid confronting the anomalous and whatever forces require privacy to operate undisturbed.

The inhabitants match the terrain in their resistance to outside scrutiny. Dunwich folk "seldom speak," harbor rumors of witch-blood and Indian rites, and are described as "decadent" and inbred. These passages reflect the racial and class prejudices common to New England writing of the period and deserve contextual understanding, but within the narrative they serve a technical purpose as well. A population that mistrusts outsiders and avoids doctors creates an epistemic boundary, information does not flow across Dunwich's borders. Their reticence is presented in specific, concrete terms, they "have come to form a race by themselves" and have developed "mental aberrations." This isolation creates conditions where unusual occurrences might persist unrecorded, unexamined by outside authorities or scientific observation.

The cost of this epistemic boundary extends beyond mere concealment into the transformation of truth itself. Knowledge that does not circulate cannot be corrected, contested, or placed into broader context. When the text notes that "no one, even those who have the facts concerning the recent horror, can say just what is the matter with Dunwich," it suggests that even direct witnesses struggle to integrate their observations into stable understanding. Without the corrective pressure of outside verification, local understanding hardens into forms that serve purposes other than accuracy. A partial truth, that something strange happens on the hills, becomes wrapped in interpretations that render it simultaneously acknowledged yet effectively concealed.

In the Archive, we often encounter this pattern, isolated communities develop systems of knowledge that function primarily to manage anomaly rather than investigate it. The explanatory frameworks provided by folklore allow phenomena to be named without being truly comprehended, creating a dangerous equilibrium where the extraordinary persists alongside daily life, neither fully confronted nor entirely denied. The boundary serves not merely as absence but as protection, both for the community that wishes to avoid scrutiny and for whatever forces benefit from that isolation.

Folklore enters the chapter as a form of indirect evidence, revealing both what has been observed and how it has been misunderstood. The elders speak of underground voices answering forbidden prayers, of strange odors around the hilltop stones, and most memorably of whippoorwills that gather at a dying person's window to catch the departing soul. What makes this folklore notable is its specificity. These are not general superstitions, but place-bound observations, voices heard "under the hills," smells perceived "around the great circles of stone." The text treats local tales not as quaint beliefs but as potentially misunderstood phenomena with consistent patterns of location, timing, and sensory manifestation.

The danger lies in how these accurate observations become trapped within interpretive frameworks that cannot contain them. When Dunwich residents report "a Rattling and Rolling, Groaning, Screeching, and Hissing, such as no Things of this Earth cou'd raise up," they have recorded the phenomenon correctly but interpreted it within conventional theological categories,"Azazel and Buzrael, of Beelzebub and Belial," that distort rather than clarify. This misattribution may be more dangerous than complete ignorance. To name something incorrectly is to place it within a system of meaning where it does not belong, rendering it simultaneously visible and invisible.

The residents see the strange behaviors of whippoorwills but explain them as psychopomps waiting for souls. Each incorrect naming creates the illusion of comprehension while foreclosing actual understanding. The phenomenon is contained within language that cannot possibly hold it, creating a precarious arrangement where the extraordinary is simultaneously present and disguised. This is perhaps why folklore persists so stubbornly in places like Dunwich, it offers the comfort of explanation without the burden of confrontation.

These layers of containment, physical, social, and semantic, interact as a dynamic system rather than a static arrangement. The hilltops with their stone circles form the most visible container, physically capping whatever lies beneath. The community's silence prevents information from spreading. Folklore provides inadequate explanations that nonetheless satisfy the need for order. What appears as passive description reveals itself, through accumulated detail, as something closer to a mechanism, one that responds actively to threats against its stability.

We see this most clearly in how the community reacts to Reverend Abijah Hoadley's sermon, which the text presents without elaboration, "Mr. Hoadley disappeared soon after delivering this sermon." The single sentence suggests the community's method of managing those who peer too directly beneath the established order. Whether this custodianship serves to protect the world from what lies beneath Dunwich or to protect what lies beneath from the world remains deliberately unclear. But the system's capacity for self-maintenance, for enforcing its boundaries through silence, forgetting, and perhaps more direct means, emerges as one of the chapter's most unsettling implications.

The opening chapter situates Dunwich within a recognizable New England geography while inverting conventional narrative priorities. More words are devoted to the "symmetrical stone circles" and "Devil's Hop Yard" than to any human figure, suggesting that whatever horror awaits will emerge not from individual psychology but from something embedded in the land itself, something older and more expansive than human affairs.

This inversion makes an implicit demand of the reader, one that becomes clearer only through the full narrative. It asks us to set aside expectations that human motive or character will provide the interpretive key. The landscape is not merely setting but participant, perhaps even instigator. The hills with their "too rounded" symmetry are not background but foreground. By devoting such sustained attention to terrain features, folklore patterns, and community silence, the chapter teaches us to read differently, to recognize agency and intention in places we might otherwise overlook.

In reflecting on this opening now, one sees how it establishes a distinctive narrative architecture, a world where perception is unreliable not because witnesses are deluded, but because the most important truths may be deliberately buried beneath layers of topography, superstition, and enforced forgetting. The chapter teaches a way of seeing that will be demanded later, when facts become more fragmentary and witnesses more uncertain. It trains readers to notice patterns, to question symmetries, to doubt conventional explanations, and to recognize the significance of what is not said as much as what is.

This training in attention is perhaps the most valuable aspect of Lovecraft's opening, particularly when viewed through the lens of the Archive. The careful custodian learns to notice what has been deliberately overlooked, to question absences as much as presences, and to understand that some silences speak louder than words. In this way, the descriptive opening becomes not merely scene-setting but an education in the ethics of observation, a lesson that extends far beyond Dunwich itself.