6,67 €

Mehr erfahren.

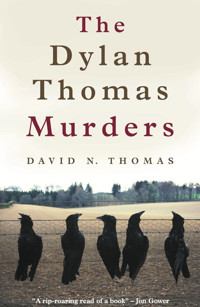

Waldo: a loner, an obsessive, the son of a famous writer - but which one? His mother Rosalind: did this old lady really work for MI5? Rachel: poet, Jew, Quaker - why is she taking such risks for the sake of friendship? Martin: her husband: retired academic, amateur detective, who is tested to the limit by events past and present in his new home in rural Wales. In this chilling mystery winding around the secret life of Dylan Thomas, each of the characters is confronted by the legacies of parents to their children. None of them could guess how stories from the past would shape their lives, and plunge them into elemental and dangerous relationships of their own. Set in the Aeron Valley and in Corsica this intriguing and ingenious novel is imbued with the spirit of Dylan Thomas. It marks a chillingly authentic fictional debut.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 281

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2002

Ähnliche

Seren is the book imprint ofPoetry Wales Press Ltd Nolton Street, Bridgend, Wales

www.serenbooks.com

© David N. Thomas, 2002

ISBN 1-85411-639-0 (EPUB edition)

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder.

The publisher works with the financial assistance of the Arts Council of Wales.

Cover photograph: George Logan

Ebook conversion by Caleb Woodbridge

For Stevie, Siân and Danny

The Dylan Thomas Murders

David N. Thomas

Fast Forward 1

Out of a bower of red swineHowls the foul fiend to heel. I cannot murder, like a fool, Season and sunshine, grace and girl, Nor can I smother the sweet waking.

The Sergeant leaned across the table, and switched on the tape machine. “Now then Les, the bloke had his head bashed in, the crows were pulling out his brains like worms.”

And Les, still dreaming of topless gypsy dancers, and wondering if he’d caught anything from a tasselled Andalucian nipple dunked in his wine glass, said: “The first time I saw him I was in Miss Hilton’s front garden, cutting the heads off in the borders, that’s what she asked me to do. A car pulled up, a big red Volvo, with a black roof rack, and National Trust stickers, not local. He got out, there was no-one else in the car with him. He came up the garden path. He had to go past me to reach the cottage but he didn’t say a word. Miss Hilton answered the door. ‘Stillness,’ he said, holding out his hand. ‘Acquisitions and Disposals.’ I couldn’t see her face but she sounded very surprised. ‘Good heavens,’ she said. They went inside and I carried on in the border.

“Yes, definitely Stillness. No, I didn’t catch his first name.

“Ten minutes later, Waldo turned up, angry, black as thunder, nostrils wide like a dog outside the butcher’s. He sniffed round the car, not bothering I was there, then he emptied this plastic bag over the windscreen. Jesus, guts everywhere, blood and slime, and big rolls of intestines which he wrapped round the wipers. Then he went to the back of the car, took something from his pocket, and jammed it hard on the exhaust pipe. A rabbit’s head, fresh too, by the look of it.

“No, I didn’t say anything, it’s not my place. We know he’s not always right in the head, but we look after him as we can. He’s one of us, and that’s good enough for me.

“Dylan Thomas? I know nothing about him and Waldo.

“Anyway, Waldo ran off across the fields and I thought I’d better get out of the way, so I went round the back. Next thing, this Stillness was marching across the lawn, shouting and swearing. I told him I knew nothing about it. He threw a punch and I hit him back solid in the stomach, and he went down, just a bag of wind, nothing to him. He fetched up and I fetched the bike. I went up to the square to sit with the lads. He came past later, driving like fury, but I don’t know how far he’d have gone with a rabbit’s head on the exhaust.”

And the Inspector, who’d once known the real Polly Garter down in New Quay, pulled out his notebook and said: “Dylan Thomas wrote wonderful poems.”

“Isn’t it funny,” remarked the Sergeant, “how most poets die young.”

“My father said it was the biggest funeral he’d ever been to.”

“My auntie says he died of AIDS in New York.”

“I believe,” said the Inspector, dreaming of a Ferris wheel in which Dylan aficionados turned forever, “that the CIA had him put down.”

Between Lamb and Raven

Rachel and I had moved to west Wales into very early retirement. We’d spent the first two weeks unpacking our books. We would start after breakfast with good intent but within minutes we’d each find some old favourite and we’d spend the rest of the day reading. In the very last box, I found a pamphlet,The Forensic Examination of Stomach Contents, written by my uncle Jack, sometime a Chief Superintendent. The cover was splattered with faded blood stains, but Jack would never explain how they came to be there, though he wasn’t slow to tell you the pamphlet had come first in the King’s Essay Competition in 1948.

There have always been policemen in our family. My brother is a detective specialising in Internet fraud. Though my father hadn’t actually been a policeman, he’d been a personnel manager at Butlins, which was much the same thing. His cousin Will, the shabbiest man I had ever seen, had been in Special Branch, and collected Victorian typewriters. We didn’t talk much about him. He had once seduced my step-mother whilst my father sat sozzled on the sofa downstairs. My step-mother was good at that sort of thing. She’d even worked in a Bloomsbury hotel, renting out rooms to blue movie makers, and starring in one or two herself. “Iesu mawr,” she said a few hours before she died, whilst I was wiping her bum, “those boys had willies down to their knees.”

Leaving London for the countryside was all very well, Rachel had said, but I would soon need an interest, capital letters, and it was finding my great-uncle’s pamphlet that gave me the idea. I had policing in my blood, a good intuitive sense about people, and a sociologist’s eye for the quirks of human behaviour.

“How about private investigation?” I said one evening, having searched through Yellow Pages and found a dearth of country gumshoes.

“Good idea,” she replied, without losing concentration on the bacon omelette she was making. “You’ll be very good at it.”

So that night, as enough rain fell for a year and the river burst its banks and took away our seed potatoes, I planned a different kind of future. I rented an office under the town clock in Lampeter, put ads in the papers and filled in a card for the noticeboard at the supermarket. I phoned the local solicitors to tell them I’d started up, and one sent me a good-luck present the next day – a desk, three odd chairs and a wooden filing cabinet containing a photograph of Diana Dors with a pencilled-in moustache. I sat in the office for two weeks and my only callers were the postman with his circulars, and shoppers asking the way to the discount store. Then one day a plump and rosy-cheeked woman came in, whose grey hair swirled round her head like smoke. She was wearing a hand-knitted, bright blue cardigan that waterfalled from her shoulders, stopping within a ragged inch of the top of her black wellington boots. A farmer’s wife, I thought. She sat in the chair facing me, folded her arms and leaned across my desk: “Mr Pritchard? Mr Martin Pritchard?”

“How can I help you?”

“They tell me your wife’s a poet.”

I nodded, too surprised for words.

“You’ll need her help to investigate this.” She drew out a copy of theCambrian Newsfrom her shopping bag. She thumbed through the inside pages, found what she was looking for, folded the paper in half, and edged it across the desk for me to read. I put on my glasses and read the report: a shed had been stolen from a field near the Scadan Coch pub.

“I should be interested in this?”

“It’s part of our cultural heritage.”

“A shed?” I was incredulous.

“Would you mock the Boat House at Laugharne? The Muse sailed well enough from there.”

I picked up the office diary, and made a show of flicking through the pages, distracted by tiny red flames at the front of her mouth. Not lipstick on her teeth, because she wore none. I wondered if her gums were bleeding.

“You won’t have much in there,” she said.

“Can you meet my terms?”

“Don’t you think,” she asked, looking scornfully at me, flashing more fire from between her lips, “that the satisfaction of putting the record straight is worth more than money?”

“I’ll find the shed, in between other things...”

“Take this.” She passed across the desk a double rabbit’s paw, stitched back to back with gold and silver thread. “Now, be care-ful...” She smiled. I stared. She held her smile. I kept on staring, mesmerised by the red dragon etched across her front teeth.

I found out later that she was the only child of a prosperous abattoir owner, and taught moral philosophy at the university.

Rachel has a habit of saying: “If you’re hungry, go look for a bagel.” Fed up with waiting for nothing to happen, I took her advice. I locked the office and drove to Ciliau Aeron. The Scadan Coch was at the end of the village, next to the church. I’d been there many times before, for although we had only just moved in, we’d been holidaying in the area for years.

The landlord was a one-legged, two-fingered Irishman called O’Malley, who’d once been a leading light in the Free Wales Army. He was also part of Ciliau’s pink community, which made many local young farmers apprehensive about using the pub. “We’re all poofters at heart,” he was fond of telling them, “but some of us have the pleasure of it down below as well.” Many thought him handsome, but his face was round and his head as bald as a goose egg.

It was usual for only Welsh to be spoken in the bars, and any persistent transgressors were often asked to leave. “There’s nothing like a good thirst to help a man find his tongue,” O’Malley used to say. He was famous for his prejudice against the English, but he took to them if they had soft voices, blended with the wallpaper and tried to learn Welsh. “What I can’t stand,” I once heard him say, “is the weekenders, all turbo cars and turbo boats and bloody turbo voices.” The pub’s pride and joy was a miniature llama called Llewela, who was trained to spit at anyone with a loud English accent.

O’Malley was behind the bar polishing the pumps. I asked for a pint of Brains. He pulled it gently into the glass, placed it on the counter and handed me some olives and a laverbread dip.

“That missing shed,” I said. “How long’s it been there?”

“First world war, off and on,” he replied over his shoulder, as he went across to serve another customer. “Lorry full of turkeys going to market, pulled out of the car park and hit a wagon carrying timber. The village salvaged the turkeys but Dai Fern Hill took the wood and built the shed from it. That’s the story, handed down, like.”

I dipped another Crinkle in the laverbread and asked: “What was it used for?”

O’Malley passed across some bubble-and-squeak rissoles. “Dai killed his pigs in there. Strung them up by the back feet from the rafter, sharp knife in the neck, and a bucket to catch the blood. They say you could hear the squealing from the top of Surgeon’s Hill.”

The rissoles were delicious, made with potatoes and wild garlic. When I’d finished, I paid O’Malley, and walked down the road. I soon found the sign for Fern Hill Farm, painted in white on the side of a rusty milk churn. A piece of blue slate on the wooden gate warned: “Loose Dogs. No callers.” The gate was chained and padlocked.

I was wondering what to do when Basset the Post arrived, a man so lugubrious that the rims of his sunken eyes seemed to fall down his cheeks and rest on his droopy, always-damp moustache. “Wouldn’t go down there, if I were you,” he murmured dolefully.

“How d’you deliver the letters, then?”

He nodded towards a wooden box next to the churn. “He don’t get much, just bills, and letters from abroad sometimes.”

“What’s he like?”

“Bitter,” said the mournful Basset.

“About what?” I tried to lighten up the question with a smile but Basset wiped it from my face with a melancholic sigh.

“His woman got pregnant by the fertiliser man.”

“And?”

“They ran away to Slough.”

“And now his shed’s gone missing.”

“It meant a lot to him, that shed.”

I jumped over the gate and walked apprehensively up the track. The trees on either side had not been cut for many years, and their branches intertwined above the track, blocking out much of the daylight. I came to a second gate, also chained, and guarded by something more sinister. A line of dead birds were tied to the top rail with orange baler twine. The three thrushes I cared little about, but it upset me to see the red kite. Someone had broken its neck before tying it to the gate by its legs. Flies were buzzing in and out of its empty eye sockets, whilst little coffee-coloured maggots burrowed through the flesh. As I clambered over, its razor beak caught the inside of my trouser leg and made a small tear.

Another five minutes of walking uphill brought me to the farmhouse. It was a dilapidated building of old Welsh stone, smothered by imperial ivy and climbing roses that reached to the eaves. Ferns had taken root in the gaps between the stones, and a twisted elder grew flag-like from the chimney stack. Pigeons flew in and out of a broken bedroom window, and crows pecked like addicts for the linseed oil in the putty. I relaxed a little as I crossed the yard because I was sure there were no dogs here. The front door was open. An inquisitive sociologist, I had always told my students, should never let a threshold hold him back. I stepped inside.

I found myself in a large room that would have made the turbo-weekenders gasp both with joy and horror. There were two inglenook fires, a slate floor, white-washed walls and black-stained oak beams smothered with bunches of drying herbs. Three rabbits hung from an old bacon hook near the window.

A long kitchen table took up most of one side of the room; it was covered in rusty agricultural tools and oily parts from some engine or other, presumably a tractor. A couple of tins of rat poison sat at one end, next to a pile ofPicture Postmagazines and a bowl of rotting apples covered in vinegar flies. In one corner of the room stood a television on an upturned diesel drum, and in the other, a mattress covered over with a patchwork quilt, with a bowler hat hanging on a nail above a cracked mirror. A dozen empty Guinness bottles were lined up on the floor beside the mattress. On the wall above, was a signed photograph of a football team called AC Portoferraio, from one of the Italian leagues presumably, though I had never heard of them.

The right side of the room was almost bare. It was dominated by a large, gilt-framed canvas above the fireplace. Even I recognised it: Monica Sahlin’s famous painting of her cousin rising to heaven in a wicker-basket, looking wistfully down through a cloud of harebells. On the mantelpiece below stood a sheep’s skull with plastic miniature daffodils sprouting from the sockets of the eyes.

On either side of the chimney breast were shelves upon shelves of books and quaintly-bound periodicals, and, in the middle of the room, a small writing desk, with a chair set at an angle as if someone had just got up or was expecting to return. A blank writing pad lay on the desk, and, to one side, a tarnished pewter mug filled with sharpened pencils. On each corner stood a black and white photograph. The one on the left was a very fuzzy snap of a chubby, curly-haired man with a cigarette hanging from his lower lip. My stomach bled sour anxiety, for he looked like my father, who had only once brought me happiness and that was on the day of his dying.

The photo on the right of the desk was of an upright man in a sombre business suit, carrying a furled umbrella. Here, too, was a sense of deja vu: he looked like the men who had chased my mother for the money that my father had borrowed and never repaid. They had harassed me, too, as I was sent to the front door with well-prepared excuses: “Sorry, he’s gone to Venezuela on business, and won’t be back for six months.” I saw again the shock on my grandmother’s face when the bailiffs took possession of her house to pay off my father’s debts. This was the man who’d told me to send him half of my student grant, and made me feel it was the right thing to do; this was the man who stayed for two years in London hotels without paying his bills, was caught, imprisoned, released on probation and landed a job as general manager of a posh West End hotel, before careering downhill to Butlins. This was the man...

I moved quietly to the centre of the room and almost hit my head against something hanging from one of the beams. It was an old Corona lemonade bottle with a tapered, unstoppered neck. Inside was a little stuffed bird, or so I first thought, but when I looked more closely I was shocked to see it was actually a live wren, sitting on its own droppings, gasping for breath in the thin, warm air that managed to drop down to the bottom. I was trying to work out how the wren had been put in the bottle, when I heard someone spitting. I turned and moved towards the back of the house where a lean-to kitchen and bathroom had been built. I could see a washbasin with a pair of black shoes in it. Next to the basin was a bath, with a man bending so far in that his head was almost touching the bottom. He unfurled and stood upright. I could see something wriggling in his mouth. He turned away and spat into the lavatory bowl. He went back to the bath and leaned over, again stretching down inside. He came back up. There was a large brown spider between his lips.

I back-tracked nervously from the house, and sought refuge in the pub. O’Malley came over.

“Brains?” he asked.

“Look,” I said, holding the pump against his pull. He looked up curiously, as the flow stopped and tiny splutters of foam filled the glass. “Small sheds don’t have rafters, nothing strong enough to hold a kicking pig.”

He put down the glass, and brought across a plate of tapas. “Clams covered in pancetta, then baked.”

“Shed some light on the mystery.”

The awful pun brought a generous smile. “It didn’t stay forever with Dai Fern Hill, you know.”

“Tell me.”

“Geoffrey Faber took it to Tyglyn Aeron.”

“Faber? T.S. Eliot’s publisher?”

“The very same.” He finished pouring my beer, and placed it on the counter with all the satisfaction of a fisherman playing out his line. “Go and see old Eli. I’ll give him a ring to say you’re coming.”

I drove to Lampeter to pick up a curry. Lampeter I liked. It was cosmopolitan, just like the part of London we had left. The pasty, chapel-serious faces of the locals were leavened by the black, brown and Chinese faces of students from the college. Hasidim rubbed shoulders with farm labourers in the Spar, hippies strummed in Harford Square, and Muslim women floated down the High Street in deep purdah.

A thickening mist slowed my drive home with the take-away. I remember the table was already laid, and Rachel was in the kitchen making raita, and warming some home-made nan. After that, my memory of what happened is extremely disconnected. We sat down at the table. We lit the candles and said a silent prayer. Rachel was picking up a spoon to serve the rice, and I remember that I was trying to tear the nan bread in two. I heard the creak of the yard gate, and wondered why the geese were so quiet. I heard footsteps outside, someone moving quietly around the yard. Mably was in the back room but, instead of barking furiously as he usually did at the slightest noise, he came whimpering through the house, and flung himself trembling under the table. There was a sound of scuffling feet outside the front door – we have no lobby and the door opens directly into the room where we were eating. I remember looking over my left shoulder, and seeing a white envelope come through the letterbox, and glide down to the doormat. I went across to pick it up. No address on it, just the lines

Find meat on bones that soon have none,And drink in the two milked crags,The merriest marrow and the dregsBefore the lady’s breasts are hagsAnd the limbs are torn.

Rachel said something about the food getting cold, so I put the envelope on the table beside me and ate some mutton muglai. Then I saw the envelope move. I stopped eating, picked it up and slit open the back with my knife.

I heard Rachel screaming and the sound of her fork hitting the plate. I jumped to my feet and stood riveted as a black spider came through the slit in the envelope and worked its way towards my hand. The touch of its feet on my finger made me shudder and the envelope fell to the table. Dozens of spiders came spilling out. They scuttled across the table, some abseiling down to the floor, but most running wildly between the plates. Some of the larger ones had already clambered into the silver cartons and were now desperately trying to extricate themselves from the burning curries. I recall seeing three or four small green spiders burrowing into the pilau rice, and Rachel running to the other side of the room.

Foolishly, I picked up a nan and began swotting the spiders but the bread was not well suited to the task. I rushed into the kitchen to fetch a can of fly spray from under the sink. I sprayed it vigorously across the top of the table, Rachel angrily shouting “Poison us, go on, poison us, I would.” Then I heard something squealing with pain, the noise a small creature makes when the talons of a hawk strike through its flesh. I dropped the can and ran outside. The orange hazard lights on the car were flashing across the darkening yard. I walked nervously across. I could see the outline of a bird trapped in a layer of mist above the car. A live house martin had been impaled on the aerial.

I arrived late at the office the next morning. After a wasted hour shuffling papers across my desk, and wondering about the spiders and the man at Fern Hill, I rang the National Library. Tyglyn Aeron, they said, had been built in the early nineteenth century. Geoffrey Faber had bought it in 1930 and T.S. Eliot was a regular summer guest.

I grabbed a seafood ciabatta from the deli, and drove munching to meet Eli Morgan. O’Malley had said he was a gardener, and that was where I found him, leaning on a spade in the front garden of his small white cottage. He was tall and well-built, and looked surprisingly fit for his age. His eyes were hidden by a peaked cap, so that his face was dominated by the strong chin that jutted out like Mr Punch’s, though much broader. We shook hands, and sat on a wooden bench beneath an old apple tree. I clipped a tiny microphone onto his lapel. Old habits die slow. I had carried a tape recorder almost every day of my working life as a sociologist. I could give all my attention to the speaker, not worrying about taking notes or trying to remember what was being said. It would be just as useful in my new role as rural sleuth.

I asked Eli what he remembered about Geoffrey Faber, and let him talk away.

“I worked down there in Tyglyn as second under-gardener, vegetables mostly, which we were sending by train up to London to Faber’s house. The Head Gardener was Oaten, who came down here from South Wales with his wife and daughters, and you daren’t glance at those girls for Oaten would give you a good beating. He was a brute.

“I seldom was talking to Faber, he was one above us. He was in church sometimes, or the shop. His tongue was sharp if you was upsetting him.”

“What did he want with Dai Fern Hill’s shed?”

“Somewhere quiet to write, you see.”

“For himself, you mean?”

“Eliot.”

“Used to write in the shed?”

“That’s it.”

“Did you ever see Eliot about?”

“He would stay mainly in the house. Sometimes we would see him writing in the shed. He and Faber used to go shooting, I know that. Big bugs they were, they weren’t for mixing.”

“So Eliot didn’t know any locals?”

“Not many.”

“None you can remember?”

“Well, that’s not for me to say. But there are stories.”

We talked a little more about his prize vegetables, and then I left. As I walked down the lane, I had the uneasy feeling that someone was watching me. When I reached the car, I felt that something wasn’t quite right, though I couldn’t see what. I put the key in the door but it was already unlocked. I looked through the window but could see nothing missing or amiss so I opened the door and climbed in. I turned the ignition and started the engine. I pulled over the seat belt and snapped it in across my chest and looked, as I always did, in the rear view mirror.

But the rear view was missing. Someone had covered the mirror with a piece of paper. There was a verse on it, written in faint red ink:

Chew spidersuck wrenbitch’s bloodfountainpenned.Find meat on bones? Not his.War on the spider and the wren!

I pulled the paper off, and opened the glove compartment to keep the verse for Rachel. Inside, still oozing blood, was a ring of puppy tails, threaded together with orange baler twine.

I drove fast to the Scadan Coch and asked O’Malley for a glass of RUC, and he quickly poured a double Bushmills into a pint of Guinness. “I’ve got some tapas for you,” I said, putting the tails onto the bar. “Fry for two minutes with sage, onion and tomato and serve in a roll, your original, authentic Ceredigion hot dog, your very ownchien chaud, serve with relish if not enthusiasm.” I quick-marched half the RUC into my stomach. “Look, what the hell’s going on?”

“You been asking about the shed?”

“You encouraged me.”

“You’ve upset him somehow.” O’Malley lifted the ring of tails from the counter. “I’ll fry these over for the ferret.”

I finished my drink, and went home, taking the shortcut through the field behind the pub. As I crossed the old bridge, I could see Rachel rounding up the chickens. She was having difficulty in enticing the flighty Seebrights into the coop, and the big Sumatran cockerel was refusing pointblank to go in with the hens. I watched for a minute, enjoying the chaos, and then walked up the dark lane to the cottage.

I let myself in. I was half-way across the room when I saw the upturned bucket on the table. I padded round warily whilst I took off my coat, checked the answering machine and put the kettle on. “It’s a letter,” said Rachel, coming in with one Seebright still clinging to the top of her shoulder. “I thought it was the safest place to put it.”

I rescued the bantam and took it down the garden path to the coop. When I returned, Rachel was standing by the table, fly swat in hand, convinced that the letter contained more wild life. I lifted the bucket, and we stared at the pale lavender envelope. It remained perfectly still but even so Rachel lunged forward and began furiously beating the envelope with her swat.

I picked it up and clipped off a little corner with the kitchen scissors. Nothing came out except the smell of eau-de-cologne. We both relaxed, though Rachel kept the swat in her hand. I slowly slit open the envelope. There was a letter inside, no spiders or puppy tails. I gingerly unfolded the single sheet of paper and read the note out loud: “Come and have coffee this evening. I should like to talk about Mr. Eliot, amongst others. Yours, Rosalind A. Hilton.”

Rosalind Hilton’s welcome was warm and effusive. She insisted on giving me a tour of her cottage, at the same time reeling off the names of the talented people who had lived on the banks of the Aeron. Not just Eliot and Dylan Thomas, she said with pride, but opera singer Sir Geraint Evans at the mouth of the river. “Not to mention,” she concluded with a wink, “the new Aeron poets like Rachel Mossman.”

“My wife,” I said in what I hoped was a modest tone.

“I know,” she replied. “I like Rachel’s poetry a good deal. She’s Jewish, isn’t she?”

“Straight out of Hackney.”

“And you?”

“No. Her toy goy.”

After pouring coffee, Rosalind sat on one side of the fire, and told me to sit opposite. I asked her if I could record our conversation, and after some hesitation, she agreed. Looking across the hearth at her, I guessed she was in her eighties, like old Eli Morgan. Her face was bright and sharp, her hair tied back in a bun. Three gold rings on her right hand gleamed brightly in the light of the fire. She rolled them between the finger and thumb of her other hand, as if she were trying to hypnotise me. Though she looked small and rather frail, when she spoke her voice was so deep and powerful that her presence filled the room.

“I’ll come straight to the point, and then, no doubt, you’ll want me to start at the beginning.” I said that was fine, and then she said in a matter-of-fact voice: “Eliot and I...” She paused and I saw a faint blush on her cheeks, though it might well have been the flames from the fire “...were lovers.”

And then she began at the beginning.

“I was born and brought up in the east end of London, in Copley Street, Stepney. My mother’s maiden name was Shodken and my father, who was a tailor, was a Hintler. That was a double cross to bear, so to speak, to be Jewish in the 1930s and called Hintler.

“You smile, but it was no joke to be the daughter of Mr and Mrs Hitler, for that was what people called us.

“My parents could see which way things were going in Germany, so in 1935 they made two decisions which they thought would save our lives, or at least make life more tolerable. They changed the family name to Hilton, and we moved out of London to Ciliau Aeron, where I’ve lived ever since.”

“Why Ciliau?”

“Geraint our milkman was always going on about how pretty it was.”

“He ran the dairy in Copley Street?”

“Two cows in a tin shed behind the shop, and a churn pulled round the streets on a three-wheeled trolley.”

“Did your parents really think that Jews from London could hide in the countryside?”

“Perhaps it was naive but many families did the same. Lubetkin, for instance, who designed the penguin house at London Zoo. He took his family to Gloucestershire, didn’t he?”

“But why Wales?”

“It was as far away west as you could get from Europe and the Nazis. And my father had always believed that the Celts were fond of Jews. Perhaps they are, Dylan Thomas certainly was, but I’ll come to him in a minute.”

“How did you get by?”

“In the time-honoured way. My father did alterations for the bachelor and widowed farmers, my mother took in washing. And we helped out with the haymaking and other farm work. My father was also a scholar – he’d thought seriously of being a Rabbi when he was young but the Communist Party got to him first. The Welsh like scholarship so they took to him quickly.

“No, we told no-one we were Jewish because we were convinced the Germans would eventually invade. We were simply regarded as Londoners who had fled the city for a quiet country life. We were treated politely and kindly, if a little suspiciously. Within a month of being here, my parents were going to church. It caused them some pain but not much. They were both atheists and hadn’t been religious Jews since their early teens. Going to church was part of the new identity, like going to the agricultural shows and theeisteddfodau. The worst thing was getting rid of our duvets –deks, we called them – and learning to sleep with blankets. Only Jews had duvets at that time, and my parents didn’t want to keep anything that would give us away.”

“Didn’t you miss London?”

“Strangely enough, no. I already knew that I had a little talent for painting and that blossomed here in the countryside. I loved the sea, which I had only ever seen once or twice before. I could wear lipstick without being hissed at by the neighbours, some of whom were veryfrum. Here we had our own little cottage, but in Copley Street we all lived upstairs in three rooms, with Mrs Presse and her children downstairs. The lavatory was at the bottom of the garden, and we had to go through Mrs Presse’s kitchen to reach it. I didn’t miss that, I can tell you, and besides, I felt at home here.”

“Really?”

“Wales is Old Testament country – the men were Isaac and Jacob and Esau, and the villages Carmel, Hebron and Bethlehem, even a Sodom or two. You see, Wales is Palestine, Syria and Mesopotamia rolled up into one. It washeimisher.

“Social life? I had little of that in London. I was more interested in books and painting, and, besides, not many wanted to date the daughter of Mr Hitler. Down here it was better. I went on rambles with the theology students from Lampeter, and that helped both my painting and my Welsh. And on Friday evenings there was always a dance in Aberaeron. I used to catch the train in with the two Oaten girls and we had a wonderful time.