Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

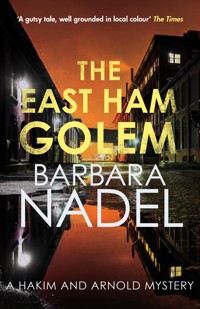

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Hakim & Arnold

- Sprache: Englisch

The streets of East London are alive with different languages, cultures and religions. Private investigators Lee Arnold and Mumtaz Hakim are well-versed in the community's tensions, the sad day-to-day reality that includes the desecration of graves at Plashet Jewish cemetery in East Ham. The vandalism of these final resting places leads to a disturbing discovery: one of the damaged coffins does not contain human remains but instead a sculpture of a man made of clay. This so-called 'golem', a term from Jewish myth given to a figure brought to life by supernatural means, proves intriguing to Arnold and Hakim, even more so when it is stolen from a police storage facility in an armed raid. The case leads the pair deep into London's past and its connections to wartime Prague, and onto the trail of a priceless jewel worth killing for.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 402

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

2

3

THE EAST HAM GOLEM

BARBARA NADEL

4

5

To all my crime writer friends especially Derek Farrell, Valentina Giambianco, Quentin Bates, Nicola Upson, Mandy Morton, Elly Griffiths, Tom Mead and everyone who leans to the side of the weird

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Prague, Czechoslovakia. 1938

‘Rudolf!’

The small, balding man ran over to his slightly staggering colleague and took his arm.

‘My God, you look terrible!’ he said as he led the tall, darker man over to a seat by the window.

Then, calling out to a young man sitting at a desk, he said, ‘Janos! Get Herr Baruch a glass of water!’

‘Yes, Herr Rozenberg.’

The young man left and Levi Rozenberg sat down next to his friend and colleague, Rudolf Baruch.

‘Was it difficult?’ he asked.

His colleague nodded.

‘Did you manage to get anything from Voss?’

Rudolf shook his head. ‘He can’t get anything now, not even aspirin. They’re strangling his business.’

Levi Rozenberg shook his head and then he said, ‘All the 8more reason we need to act fast. Today the pharmacy …’

The young man returned with a glass of water, which he gave to Rudolf Baruch.

‘Thank you.’ He drank and then said to the young man, ‘Is everything prepared, Janos?’

‘Yes, Herr Baruch.’

‘And the family?’

‘They want to visit as soon as it’s over,’ he said. ‘I told them to come this afternoon.’

‘Good.’

And then the young man, Janos Horak, said, ‘Herr Baruch, if you don’t mind my saying, you look unwell. Are you sure …?’

‘I will finish attending to Frau Zimmer and then I will go home,’ Rudolf said and then he stood. ‘Levi, are you ready?’

His colleague also rose to his feet and said, ‘As I will ever be, my friend.’

And then the two of them left their office and repaired to their laboratory.

ONE

Plashet Jewish Cemetery, East Ham, London. March 2023

‘Is it me, or does everyone think that whoever did this should be strung up by his nuts?’

The group of uniformed police officers standing beside the tall, middle-aged man struggling to keep upright on the uneven ground beneath his feet looked at each other, but said nothing.

‘’Cause, you see, I find I don’t really give a shit whatever the thinking was behind this – far-right nationalism, religion, madness – I just want to punch whoever did it until his spleen falls out.’

Still nobody spoke. Detective Inspector Tony Bracci was generally a likeable old geezer – family-orientated, friendly, fair. But he had ‘views’ which, if challenged, could land the challenger in a place they wouldn’t like. In other words, Tony had a temper he wasn’t afraid to use.

Looking around the recently desecrated cemetery, he said, 10‘Vi’s got family buried here. Don’t know how the hell I’m gonna tell her …’

A female officer said, ‘You mean Detective Inspector Collins, guv?’

‘Yes, God love her,’ Tony said. ‘If she was still in the job she’d be effin’ and jeffin’ and kicking your arses to get hold of every Nazi fanboy and would-be jihadi in Newham.’

‘So why aren’t you?’ the officer continued.

Tony shrugged and then he said, ‘Where to start these days, Siddiqui? Seems to me there’s some sort of two-for-one deal on extremists these days. Can barely turn round for the bastards. No, it’s SOCO slog for now, see whether we can get anything useful from the site, then house to house where we’ll no doubt learn that no one has seen or heard fuck all.’

He lit a cigarette while all but one of his team dispersed around the group of shattered and desecrated tombstones in the middle of the cemetery. Rather closer to the main entrance than the rest, Detective Sergeant Kamran Shah was minutely examining the most egregious offence against the dead, in the shape of a coffin which had been dug up and its lid smashed. Fragments of what could have been the corpse’s shroud stuck up from the broken lid like tiny off-white sails. If the body of Rudolf Bennett – the name he’d finally managed to make out on the scuffed metal plate once attached to the coffin lid – was to be reburied, it had to go through the hands of a police pathologist first. So Shah, as well as examining the site, was also waiting for Dr Gabor, the latest recruit to the tribe of specialists assigned from time to time to Forest Gate CID. He’d never met Gabor before, but he’d been told by his boss that the latest ‘path’ looked about twelve. 11

Tony Bracci ambled and stumbled his way over to his sergeant and said, ‘So what’s the score then, Kam?’

‘Can’t see much without disturbing it, guv. Path phoned to say he wants to transport the whole thing to the lab so he can maybe see why they picked on this particular bloke.’

‘I can tell you that,’ Tony said. ‘Because he was there and because they’re twats.’

‘Yeah, but …’

Tony put a hand on his sergeant’s broad shoulder and smiled. ‘I know – look for all and any possible motives. Dinosaur I may be, but I’m not stupid. Just pulling your leg, Kam.’

The younger man smiled.

Kamran Shah had joined Forest Gate CID back in 2018 on an accelerated graduate programme. His now-boss had then been a sergeant who had worked with the legendary Detective Inspector Violet Collins. Tall, skinny and foul-mouthed, Vi had retired back in 2019, along with her signature Chanel suits, Opium perfume and famous preference for younger male lovers. What she hadn’t taken with her was the dark sense of humour she had shared with Tony Bracci. It was something Kam Shah had learnt to appreciate – especially during the frightening days of the recent Covid pandemic. Like most police officers, Tony and Kam had worked all through what became known as ‘the virus’, trying, often in vain, to get people to obey the heavy quarantine restrictions that had been in force back then.

Kam said, ‘But they are twats anyway.’

‘’Course.’

The entrance gates to the cemetery swung open and 12a black transit van reversed in. When it finally stopped, a young man with flaming-red hair and Harry Potter glasses got out and opened up the back doors. Dr Benedict Gabor, police pathologist and, it was said, a practising pagan, was not a man who waited for ‘inferiors’ to do the donkey work allied to his profession. Pulling a trolley out of the van while two of his mortuary attendants looked on, he nodded at the coffin and said, ‘This our man?’

‘Yes, Doctor,’ Kam said. ‘Called Rudolf Bennett.’

Dr Gabor liked to have names for his ‘people’ where possible. Observing the shattered coffin, he said, ‘Makes you wonder, doesn’t it?’

‘Wonder what?’ Tony said.

‘Why …’

‘As I said to Kam here earlier,’ Tony said, ‘it’s because they’re twats.’

Gabor nodded and then said, ‘It’s as good an explanation as any.’

While Tony Bracci and his team were searching Plashet Jewish Cemetery for clues to who had desecrated the site, Private Investigator Mumtaz Hakim was drinking masala chai at a house that backed onto the graveyard. The owner of the house, a Mrs Meera Dhawan, had invited her to talk about her younger sister, Lakshmi.

‘She’s what my husband calls an “airhead”,’ Mrs Dhawan said as she crossed one elegant leg over the other. ‘Thirty going on seventeen.’

It was nice to be given a cup of proper home-made masala chai. The spice-flavoured milk tea was ubiquitous all over the 13entire Indian subcontinent – though in the UK, as Mumtaz knew all too well, a lot of British Asians now opted for pre-mixed spice blends. But then Mrs Dhawan was the proprietor, with her husband, of three Indian restaurants across the London borough of Newham, as well as the ‘star’ of a highly regarded Asian cookery blog. Her masala chai was heavy on the ginger, which Mumtaz loved.

‘Maybe,’ Mumtaz said, ‘that is why she is attracted to this much younger man.’

‘You could have a point,’ Mrs Dhawan said. ‘But to want to marry an eighteen-year-old! I mean, who does that?’

‘Other teenagers? If as you say your sister is still behaving like a teenager herself, she may very well find this boy appealing.’

‘Yes, but she’s a lawyer!’ Mrs Dhawan said. ‘I mean think about the optics of that? What on earth will her clients think of her? Lakshmi works with our father at his solicitors’ practice in Chingford. Together with our brother Dev, they have some very important clients, high-profile people in our community.’

Unlike Mumtaz, a Muslim, the Dhawan family were Hindus. Meera and Lakshmi’s father Dilip Dhawan was a well-known and respected solicitor across east London, especially amongst Hindu families. It must have come as a huge shock when the younger of the two Dhawan sisters announced that she wanted to marry a white teenage boy she’d met at the gym.

Shouting voices from the nearby cemetery insinuated themselves into Meera’s smart, very grey living room and she looked towards the patio doors. There was no way she could 14see anything, but the police had been in there since very early that morning and their presence was unsettling – because it probably signified that the cemetery had been vandalised again.

Mumtaz, who had noticed the clutch of police vehicles at the entrance to the cemetery, said, ‘It must be worrying for you when people get into the old graveyard.’

‘It is,’ Meera agreed; then she turned back to Mumtaz and said, ‘All this hatred these days. Even levelled at the dead. Just because they were Jewish. I mean look at us. You are a Muslim, I a Hindu, but we get along with each other, we do business, talk like rational human beings.’

‘It’s men mainly, who do these things,’ Mumtaz said. ‘Most women don’t have time for such things.’

‘Oh, that is so true!’ Mrs Dhawan said. ‘Men and boys chewing betel all day long and talking about politics they barely understand. They want to try raising children, keeping house and pandering to the orders of men like themselves all day long!’ Then she shook her head. ‘Sorry, Mrs Hakim, ridiculous men are my bête noire. Like you, I’m a working British Asian woman who really doesn’t have time for the prejudices of men. And I don’t just mean Asian men either. I told Lakshmi, this white Christian boy of hers will be no better. I give it a year before he’s got her picking up his dirty socks and then leaving her to go down the pub.’

Mumtaz smiled. Her own on-and-off lover was white, but he’d never made her pick up his socks and he had certainly never left her alone to go to the pub. Lee Arnold, for all his faults, was teetotal.

‘Anyway,’ Mrs Dhawan said, ‘I’d like to find out more about this Danny Hall my sister has taken up with.’ She passed 15Mumtaz a photograph of a slim, dark-haired teenager who wore a slightly challenging expression on his finely chiselled face. ‘He lives in Canning Town with his parents and, so my sister says, seven younger brothers and sisters. Given the size of the family, I do wonder whether they’re Travellers. But you’ll probably find that out.’

Mumtaz bit her tongue. Prejudice against Travellers and Roma was rampant and she really didn’t want to get into that with this woman. Maybe Danny Hall did come from a Traveller family, but if he did, so what?

‘Danny himself attends that NewVic College doing some course or other – when he’s not with my sister,’ Mrs Dhawan said. ‘His mother cleans for a living, which is honourable, but the father is unemployed. Sick apparently.’ She rolled her eyes. ‘I want to know whether they’re in debt. I don’t want my sister used as a human bank and I want to know whether they’re involved in crime. I’m not a fool, I know that not everyone involved in crime has a record. I could follow the boy myself, make forays down to Canning Town and ask around about these people, but you’re better than I am at all this, and you have contacts.’

Mrs Dhawan was right. Although the next time Mumtaz would be in the vicinity of Plashet Jewish Cemetery, in three months’ time, it would be in connection with what the police were doing in there right at that very moment.

By that time, Lakshmi Dhawan and Danny Hall would have been married for three weeks.

The whole process was recorded as well as individual photographs taken, from the time the shattered coffin 16was placed onto plastic sheeting on the floor. As each piece of broken wood was carefully removed it was numbered, photographed and laid in its approximate place on top of the coffin, but now on a bench. Just removing the lid took over an hour. And when the final piece was removed, Benedict Gabor had to decide whether to remove the shroud in situ or once his team had lifted the whole thing onto his examination table. While the table itself was covered with plastic sheeting, the doctor wanted to avoid any residual clumps of earth and other outside elements contaminating his work area. However, to remove the shroud in situ did mean pulling it from underneath the corpse, which could create damage.

In the end his team of technicians removed the enshrouded body and placed it onto the examination table. Gabor noticed that they struggled with the weight and wondered what, if anything, the body might have been buried with. The only woman on the team, Rosa, was left temporarily breathless.

When she could speak again, Rosa said, ‘Weighs a ton!’

Her male colleagues all nodded their agreement while Benedict changed his nitrile gloves and then, with the aid of tweezers, began to pull at one corner of the shroud. From the date on the brass coffin plate, it would seem that Rudolf Bennett had died in 1940 and so he was probably way beyond liquefaction. But even when dealing with desert-dry skeletons, it was still surprising how fabric particularly could stick to a corpse. And this skeleton was heavy, or something was. As Benedict began to peel away the upper layers of the shroud, he sensed that what was underneath was rather more substantial than a skeleton.

Had the family of Bennett had the body embalmed? And 17if so, to what degree? When Benedict’s own father had died, he had been subjected to a high level of preservation. At the behest of his only surviving sibling, his sister Eszter, the body of Viktor Gabor had been mainly formaldehyde when he’d been buried. Benedict had been surprised. He hadn’t thought that Jews were big on body preservation. But then what did he know? With Benedict brought up a Gentile by his Gentile mother, Viktor’s original identity as a Jewish Hungarian was, and remained, a mystery to his son.

Benedict asked his team to lift the body while he disentangled the shroud from the underside of the corpse. This happened three times before first the head and then one shoulder came into view. And while the face, as might be expected, was covered by thick if discoloured gauze, there was something about the shoulder than made the doctor take a step back for a moment and breathe.

Benedict recapped. Not only was the corpse unusually heavy, but the shroud appeared to have been wrapped around it in a haphazard way. That, or maybe those who had attempted to remove or destroy Rudolf Bennett had rewrapped him after they’d finished whatever ghastly thing they had done to him. And yet the gauze over the face was intact and, when he pulled at one corner of it, it came away easily.

Benedict looked. Then he blinked several times to make sure that what he was looking at was real. A long aquiline nose dominated a grey-tinged face whose startlingly vivid blue eyes looked up at Benedict with … what? Stepping back from whatever this was, Benedict said, ‘Christ!’

‘What the hell is it, Doctor?’ one of the technicians asked. 18

Quickly, as if more protracted contact with Rudolf Bennett might taint him in some way, Benedict pulled the shroud down to the body’s mid-section – and then they all looked, with a mixture of horror and confusion, as the moulded chest of what looked like a tailor’s dummy came into view.

TWO

June 2023

‘They called it the East Ham Golem, unofficially like.’

The small, dark man sitting in front of her wore a soft brown hat and a lot of thick gold jewellery, especially on his left arm, which was probably an attempt to cover the huge scar there. He told her straight off the bat that some of his neighbours called him a ‘pikey’ behind his back. ‘I actually like the travelling folk myself,’ Bernie said. ‘So I don’t take it badly.’ Turned out that Bernard Bennett was, at least in part, Jewish.

‘Back in March I got a call from the Old Bill,’ Bernie said. ‘Now I know you probably look at me and think, geezer like him is a dead cert for a visit from the law—’

‘Lee has told me you work at Newham General,’ Mumtaz said.

‘Yeah, I’m a cleaner.’

Sixty-year-old Bernard Bennett lived in the same street as 20the mother of Mumtaz’s business partner, Lee Arnold. Lee, a former soldier and copper, had started the Arnold Private Detective Agency when he’d left the Metropolitan Police. When business picked up, he’d employed Mumtaz, a psychology graduate, as a trainee investigator. The two of them had been together, both as business partners and sometimes lovers, ever since.

‘So you clean at the hospital …’ Mumtaz prompted.

‘Yeah. Right,’ he said. ‘So I get this call from the police. It’s about me grandparents’ graves in the cemetery up Plashet. Apparently some bastard’s been in there desecrating the graves.’

‘I remember,’ Mumtaz said. ‘I was actually with a client who lives in one of the houses that back onto the cemetery the day the police began their investigation. Your name was never made public, was it?’

‘No. Wouldn’t have it.’ Bernie leant forward in his chair and said, ‘Do you mind if I have a fag, Mrs Hakim?’

‘You can’t smoke in the office but if you don’t mind going out on the steps outside, that’ll be OK,’ Mumtaz said.

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘Only Rose, you know, Lee’s mum, she told me it was alright to have a snout in his place.’

‘It’s against the law, Mr Bennett,’ Mumtaz said. ‘We could get shut down. I tell you what, it’s nice and warm outside – we can sit on the metal stairs if you like and I’ll make us both a cup of tea.’

The Arnold Agency’s one office was over a kebab shop at the Forest Gate end of Green Street, Plaistow. The office was accessed via a back alleyway and a steep flight of iron stairs, with the windows at the front looking out onto the large, 21modern Forest Gate Police Station building. Lee Arnold had worked there back in the day, and it was partly because he was an ex-copper that Bernie Bennett had come to see him now.

‘I’m sorry Lee can’t be here today, he had to be in court,’ Mumtaz said as she gave Bernie a cup of tea and then sat down beside him on the iron stairs.

‘That’s alright, love,’ Bernie said.

Mumtaz wondered what, if anything, Rose Arnold had told Bernie about her. When he’d arrived she’d got the feeling Rose hadn’t told Bernie she wore hijab. He’d looked a bit shocked.

Now with a cup of tea in one hand and a fag in the other, he continued, ‘So I had to go up Plashet Cemetery and have a look. I own the gravesite now my dad’s dead. By the way, his grave wasn’t disturbed at all, just my granddad and grandma’s.’

‘I know the detective who worked on the case, Tony Bracci,’ Mumtaz said.

Bernie smiled. ‘He’s a bit of a sort, in’t he?’

Mumtaz could imagine Tony ranging around the cemetery, swearing.

‘It was Granddad’s grave where they found the statue. Properly weird, I can tell you!’

‘You saw it?’

‘Yeah. Police asked me whether it looked like him, but how the hell should I know? He died during the war when my dad was just a baby. No photographs of him I know of. This statue was a man, dark hair, blue eyes, made to look quite young, like Granddad would have been. You know what a golem is, Mrs Hakim?’ 22

Mumtaz had looked the word up when the story had been in the news.

‘As I understand it, a golem is a clay figure,’ she said. ‘Created by rabbis to protect the Jewish community.’

‘Magical,’ Bernie said. ‘I don’t know how, I don’t believe in all that stuff. I don’t believe in nothing. Dad’d put down he was Jewish on forms and that, but me mum wasn’t Jewish and so I never went to synagogue. I knew nothing about it until all this business come up. But now it has come up …’

‘What do you want from us, Mr Bennett?’ Mumtaz asked.

He sighed. ‘They found my grandma’s body, the police,’ he said. ‘Chani Bennett she was called, but Granddad’s still out there somewhere.’

‘The police never recovered his corpse?’

Mumtaz hadn’t seen Tony Bracci for months, time during which the story of the Golem of East Ham had just sort of faded away.

‘No,’ Bernie said. ‘Size of that golem they found in his box, there was no room for the body. The statue they’ve got in some storage place somewhere, but Granddad has never shown up. But then he wouldn’t. Must’ve gone before his funeral. Unless of course someone took him out since at some point. I dunno, but it bothers me. Rudolf Baruch was his real name and the way my dad used to tell it, he was a brave man. He come here on his own from Czechoslovakia in 1938 when the Nazis took control. He worked doing anything he could get, but Grandma was always the real breadwinner. She was born here and worked as a dressmaker. Chani outlived Rudolf by thirty years, never married again, and when she died she was buried alongside him because that was where 23she wanted to be. Now me dad’s in there an’all, but with me granddad gone, it ain’t right.’

‘So you want us to …’

‘Find Rudolf,’ Bernie said. ‘Something about him, who he was, if you can. And his body. Police don’t say they’ve given up, but they have and I understand it. Why look for a dead bloke who maybe went missing in 1940, when the living need so much help? Don’t make no sense. Rosie told me I’d have to pay and I will. My wife died three years ago and me daughter’s married with kids so I work most of the time. What else is there to do?’

‘Mr Bennett—’

‘Bernie,’ he said.

She smiled. ‘Bernie. I’m Mumtaz, and of course we will try and find out as much as we can about your grandfather. Whether we will be able to locate his body is less certain. No arrests were made in connection with that crime and so it’s not as if we can ask the perpetrators where they put Rudolf’s body – even if they took it, which looks unlikely.’

‘I know it’s a long shot.’

‘But for the time being,’ Mumtaz said, ‘let’s see if we can find out more about Rudolf. Do you know whether he had any other family members in the UK?’

‘No, like I said, he come here alone. I’ve still got some paperwork of me dad’s at home so there might be something in there, but I don’t think there’s anything about me granddad,’ Bernie said. ‘Chani’s family name was Freedland. I do remember her from when I was a kid, but I dunno what family she had. I know she died in the Jewish Hospital in Stepney Green because Dad took me to see her before she 24passed. But I don’t remember anyone else being there. Don’t mean they weren’t. I was just a kid at the time, and ’course there was the look of her too what took my mind away from anything else.’

‘The look of your grandmother?’

‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘Like a living skeleton she was, and her skin was the colour of nicotine. Cancer.’

Lee Arnold leant back against a listing weeping angel and lit a cigarette. ‘Death by Misadventure’ was the verdict the coroner had handed down. It had satisfied Kathy’s dad, who had travelled from Ghana for the hearing. Ninety years old, he’d just wanted closure. Not so Kathy’s brother, Ezra Appiah. He had walked out after the verdict and Lee didn’t blame him. Anyone who’d known Kathy Appiah even slightly during the last year of her life knew full well she’d killed herself. Or rather been murdered. The trouble was that Kathy’s killer had been nowhere near her when she died. He’d been in Russia.

Kathy Appiah had been a nurse at the London Hospital in Whitechapel for nearly twenty years when she died. A committed Christian, sixty-year-old Kathy had lived alone in a one-bedroom flat in Plaistow, sending half of what she earned to her family in Ghana, mainly towards the education of her sister’s children. Everyone who met Kathy had loved her. Her patients, her neighbours, the people at her church. Always happy when she made contact with her relatives via the internet, Kathy had also met a lot of other, apparently like-minded, family-orientated people online. A lot of them were not as fortunate as Kathy, and she soon became aware 25of how much misery there was in the world outside her immediate circle. Over the years she sent small amounts of money to a single mother in Lebanon, an animal refuge in Syria and a man who needed to save up for surgery in Cameroon. Then she met Vladimir.

Vladimir was twenty-six, tall and blond and really didn’t want to go to war against Ukraine. He had nothing against Ukrainians and wanted nothing more than to leave Russia and make a new life somewhere in Western Europe. At first Kathy merely commiserated with ‘Vlad’, but as their communications became more frequent, she realised that she was falling for him. He was so kind and respectful, never pushy or inappropriate. For her part Kathy looked upon Vlad as the young son she’d never had – at least that was what she’d told herself. That was what she’d stuck to until one night she got a phone call from Vlad. In tearful broken English he’d told her that he’d been called up to the army and was now on the run. He feared that if Putin’s people caught him, they’d kill him. He wasn’t, he said, asking for money, but if Kathy would just reciprocate his feelings of love, at least he’d be able to die happy.

Kathy was nobody’s fool. She knew about internet scams. But she’d built a relationship with Vlad; she’d spoken to him on the phone and he’d told her she was the only person in the world who cared about him. She’d sent him five thousand pounds via Western Union to the place where he was hiding: Ekaterinburg in the Ural Mountains. Vlad had been so happy. But then they’d caught up with him yet again and so he’d had to move on. Her ‘lovely boy’ had travelled to St Petersburg, Kazan, Nizhny Novgorod and Perm in the months that 26followed, never asking for money. But she gave it to him anyway. Then her brother found out what was going on.

Ezra Appiah was Lee Arnold’s neighbour; he knew what Lee did for a living and had asked for his help to try and discover who this Vladimir was. Lee had put his most internet-savvy investigator on the job, who had discovered that ‘Vladimir’ was actually a bus company in Ekaterinburg. Hurt, humiliated and angry, Kathy had, against Lee’s advice, confronted ‘Vladimir’ online. The reply she’d received had told her she was a stupid, pathetic old woman who deserved everything she got, and asked why the hell she would think that a young attractive man like Vladimir would want her. Showing this to no one, Kathy mulled his response for a couple of days before she took a handful of sleeping tablets and threw herself down the stairs leading up to her flat.

Lee had just given evidence at Kathy’s inquest. Held at the Coroner’s Court at Walthamstow Cemetery, it had been a sad end to a life of selfless service. But in retrospect the verdict had been the right one. Nobody was going to bring ‘Vladimir’ to justice any time soon, and had the coroner handed down ‘suicide’ it would have meant more pain for her father who, like Kathy, was a committed Christian. But Lee also knew why Ezra was angry. His sister’s death had been needless and a waste and, as he’d told Lee, ‘If this carries on unpunished, how many other vulnerable women will send money to these bastards? How many more will take their own lives?’

He was right, of course. But how did you police the internet? Now that the genie of mass ‘democratised’ communication was out of its bottle, putting it back in wasn’t an option.

For Lee personally, Kathy’s death was just one more 27example of what he was coming to see as a run of bad luck for him. In the past six months he’d been pistol-whipped by a young gang member on whom he’d tried to serve court documents, his wayward daughter had gone to live with a violent cage-fighter, and his on/off relationship with Mumtaz had broken down – again. And money was tight. He needed a win. But PI work was thin on the ground, mainly because nobody had any money. He just hoped that his mum’s neighbour, Bernie Bennett, had something he could actually have a chance of solving. Not that he’d make a mint out of a man who worked as a hospital cleaner.

When Mumtaz had called DI Tony Bracci, he’d invited her for coffee. They met at what he told her was his favourite chai place on Katherine Road. When he arrived, Mumtaz could clearly see why Tony had prefaced this meeting by telling her he was ‘addicted to their Karak coffee cakes’. This was a much bigger Tony than the one she’d seen eight months ago.

Tony ordered for them both – chai latte for Mumtaz, spicy Karak coffee for him plus two helpings of delicate Genoise sponge soaked in coffee – the famous Karak coffee cake.

‘I’m in here almost every day now,’ Tony told her while they waited to be served. ‘And at the moment I can’t say I can justify it by needing to keep me caffeine levels up.’

‘You’re not busy?’

‘Well, we are,’ Tony said. ‘Antisocial behaviour has been with us since the dawn of time and will outlive both of us with no bother. But, as you know, one person’s antisocial behaviour is another person’s just living his life. ’Course, it can get serious if blades are involved but, contrary to what 28you hear in the news, crimes involving blades don’t happen on every street every day here in Newham.’

‘It’s terrible the way the stigma never detaches from east London,’ Mumtaz said. ‘Way before Jack the Ripper, the East End had the reputation for crime it still has to this day.’

‘Funny, innit,’ Tony said. ‘In spite of all the rich kids moving into the borough with their olive oil tastings and artists’ ateliers, some people still think it’s like the Somme down here.’

Their food and drink arrived. One bite of Karak coffee cake was enough to convince Mumtaz that Tony’s addiction was completely understandable.

After some moments of gastronomic bliss, Mumtaz said, ‘So, Tony, the East Ham Golem …’

She’d told him on the phone that Bernie Bennett had been in touch, and so he was prepared for it.

‘Nothing so far,’ Tony said. ‘The thing itself is down at our storage facility in Belvedere. I can send you some photographs. Just between us, like.’

‘Thanks Tony, that would be useful.’

She knew he wasn’t supposed to do that, but she’d already found one photograph online that had been leaked to one of the local free papers back in the spring.

‘What’s Bennett actually want you to do?’ Tony asked.

Mumtaz finished her cake and was tempted to go for another piece, but just settled herself to her very good chai.

‘Well, of course he wants his grandfather’s body put back in its grave,’ she said. ‘But he’s a pragmatist, luckily.’

‘We may never see that,’ Tony said. ‘All I can tell you is whoever opened that grave got in and out of the cemetery 29via the High Street North entrance. We found some fibres on the gate which could have come from the shroud that was around the statue. There was a piece missing. But unless we catch ’em …’ He shrugged. ‘Probably in some scrote’s shed somewhere. Some lone Nazi thinks he’s got one over on the Jewish Illuminati by nicking a shroud. I blame the fucking internet.’

Mumtaz smiled. Lee ranted about the internet in just the same way. The proliferation of conspiracy theories, like the one about a sinister cabal of Jewish bankers known as the Illuminati, who were planning to take over the world, was out of control.

‘Bernie is aware that you guys have got more important things to do than go looking for a dead man,’ Mumtaz said. ‘I mean, unless Rudolf’s body and the statue were in the coffin together, then the actual bodysnatching must have happened years ago. What he’s after is information about Rudolf Baruch. He knows why he came to the UK and when, but he’s no real notion of who he was. His father’s dead and Bernie’s pretty much cut off from that side of his family. The only lead I’ve got so far is the name Chani Freedland. She married Rudolf in 1939. She was British and came from Stepney Green.’

‘A lot of Jews in Stepney Green back then.’

‘But from what Bernie told me, it seems that when she married Rudolf, Chani lost contact with her family for some reason.’

‘Maybe the Freedlands didn’t like him.’

‘Maybe. Rudolf was killed during a Nazi bombing raid on London on 26th September 1940,’ Mumtaz said. ‘Chani was eight months pregnant with Bernie’s father, Morris, who 30of course never knew Rudolf. From what Bernie has told me, it seems that Chani brought the boy up alone, working as a seamstress, although I don’t know where.’

‘The old East End was full of sweatshops back in the day,’ Tony said. ‘And of course some women worked from home. Where did Rudolf Baruch come from?’

‘What is now Czechia. Prague. I’ve told Bernie that if we have to make contact with the authorities over there, it won’t come cheap.’

‘No. Any idea what he did for a living?’

‘None. He got out just before the Nazis invaded. He was twenty-seven.’

Tony shook his head. ‘Well, if I pick up anything about Rudolf, I’ll let you know.’ He sipped his coffee. ‘How’s Lee?’

She sighed. ‘He’s at Walthamstow at the coroner’s about Kathy Appiah. When I spoke to him this morning, he said he couldn’t work out what verdict he was hoping for. In spite of no note it was almost certainly suicide, but her family are devout Christians and so he hopes for their sake it’s declared misadventure. I mean, I guess that suicide would make people think more.’

‘Would it? I don’t see it, Mumtaz. It’s all based on hope innit, the internet romance thing. Everyone wants to believe it’s real, even when they know deep down that it ain’t. We all want to be loved, don’t we. Even if it could destroy us.’

Mumtaz knew. She’d wanted, against all evidence to the contrary, to believe her husband had loved her, even when he’d abused her. Ahmet Hakim had died leaving her alone with his teenage daughter Shazia, whom he had also abused. And in spite of the fact the girl had hated her stepmother at 31first, the two of them had made a life together and now Shazia was a trainee detective constable with the Met. Mumtaz was the only female British Asian PI in east London, as far as she knew. She was also engaged in an on-and-off affair with her white British boss, who did love her. She in turn loved him too, but at the moment, he wanted commitment while she wasn’t ready. Mumtaz had done marriage once and hadn’t liked it.

Her legs were bad and so Bernie Bennett knew he’d have to let Rose Arnold in rather than trying to talk to her on his front doorstep. He lived in one of the older houses on Shipman Road, while Rose was in a council place at the top of the turning. Knowing how slow she was now, he reckoned it must’ve taken her ten minutes to get to his place.

‘How’d you get on with my Lee? He sort you out?’ Rose said as she stepped painfully into Bernie’s hallway.

After settling Rose down on the sofa in his living room, Bernie made tea for them both and brought some clean ashtrays. While Rose lit up, he said, ‘I never saw Lee, saw Mumtaz.’

‘Oh. Where was he then?’ Rose asked.

‘Court. But didn’t matter. I told her about it, and she said she’d try and help. She’s nice, in’t she? But you never told me she covered her head.’

‘Oh, yeah,’ Rose said. ‘I don’t get it, Bernie. Schtupping my boy and yet she wears that. I like her. Lee’s besotted, but I think he’s on a hiding to nothing. She’ll end up marrying one of her own.’

‘You never told me they was schtupping,’ Bernie said. 32

‘Oh, yeah.’

As children of Jews, albeit on only one side of their respective families, both Rose Arnold and Bernie Bennett lapsed into Yiddish from time to time. Besides, ‘schtupping’ sounded so much better than ‘fucking’.

‘So what’d she say, Mumtaz?’ Rose asked.

‘Said she’d give it a whirl,’ Bernie said. ‘Try and find out as much as she can about me granddad. But she was not hopeful about his body.’

‘Oh, Lee’ll help you with that, love,’ Rose said.

‘Don’t know that he can,’ Bernie said. ‘Like Mumtaz said, the coppers can’t waste time looking for a dead bloke, can they?’

‘Ah, but my Lee knows people, Bernie.’

‘What people?’

‘People you wouldn’t want to meet down a dark alley.’

Bernie took Rosie home when he left to do his shift at the hospital. It was a nice sunny evening by that time, but rather than feeling better now that he was actively seeking Rudolf, he felt depressed and a little bit paranoid. What was he going to find out about Rudolf – if anything? His body was long gone. It had probably been missing for decades. Did the golem look like Rudolf, or was it just a statue of some other man? Had Rudolf even died in 1940? Bernie got on the bus and tapped his Oyster card. As he sat down, he looked at the man sitting behind him for a moment and then slumped down with his chin on his chest. If only it were winter, he could hide in his overcoat.

THREE

The face, if not the body, was well made. A man with black hair, a long Roman nose (rather like Lee’s) and startling, aquamarine-blue eyes. Its mouth, whose lips looked fleshy, was slightly open, leading Mumtaz to wonder whether the artist who’d created it had put a slip of paper into its mouth.

While keeping the photographs Tony had sent her on her laptop screen, Mumtaz had also opened up various windows containing more information about golem legends. Created by Kabbalists – sort of magicians – to protect the Jews in places like Prague and Vilnius, they were ‘mud men’ made of clay which, via a succession of spells, could be animated to disable or kill the enemies of the community. As far as she could tell, a golem could only be killed or deactivated in one way, and this was where the paper in the mouth came in. On the paper, the magician, who was also usually a rabbi, would inscribe the word emet – meaning truth – prior to performing 34the ceremony of activation. So if the golem began to go out of control, the magician/rabbi could take the paper out of its mouth, cross out the initial ‘e’ (aleph in Hebrew) which would leave the word met, meaning death. At this point the golem would ‘die’ and turn to dust.

This thing had been dubbed ‘the East Ham Golem’ by the press. But was it a golem or was it just a mannequin made out of clay? Because it had been found in a Jewish cemetery, ‘golem’ had probably been too tempting a term to avoid. But in reality it was simply a statue of a man. What made it unsettling was where it had been found. Someone had buried it, probably with all due ceremony, in a grave meant for a real corpse.

Mumtaz sent Tony Bracci an email with some further questions.

Her phone rang, and without looking at who was calling she picked it up.

‘Mumtaz,’ she heard Lee say. ‘Are you busy?’

‘I’m looking into Bernie Bennett’s case,’ she said.

She was, but also she didn’t want to talk to Lee – not unless it was in the office, about work.

‘I was wondering whether I could come round?’ he asked.

She’d spoken to him briefly, just before she left the office, and knew that Kathy Appiah’s inquest had upset him.

‘I’m really into this golem thing,’ she said. ‘Is it urgent?’

There was a pause and then he said, ‘No. Just …’

‘How are Ezra and his father?’ she cut in.

‘Ezra’s taken the old man down the pub,’ Lee said. ‘They wanted me to go with them but …’

‘So go if you’re lonely,’ she said. ‘I’m sure they’d like the company. Where have they gone?’

‘The Holly Tree.’

‘That’s a lovely pub,’ she said. ‘And just down the road from you. Lee, they asked you to join them for a reason. Ezra probably needs some support with his dad. I’d go.’

‘I wanna talk to you!’

That was quite an outburst, if not unexpected. Five months ago when she’d told him that she wanted to take things more slowly, Lee had been devastated. Had it been the first time she’d pulled away from him, it wouldn’t have been so bad, but it wasn’t. Their relationship was conforming to a pattern that wasn’t healthy. And although Lee didn’t have a psychology degree like Mumtaz, he knew it. They’d start their relationship as friends and sometimes lovers and within weeks Lee was asking her to move in with him. Then talk quickly turned to marriage. Then Mumtaz stopped it.

Again, she would explain how her years of marriage to her violent husband Ahmet had made it very hard for her to trust any man, which Lee would counter by asking her whether she was going to let a dead man define her life for ever. But Mumtaz’s reluctance to commit to a relationship with Lee was about more than memories of the horror of her marriage. It was also about the fact that now she was free, she valued that. As a stepmother devoted to her stepdaughter, as a professional working woman and as an observant Muslim, Mumtaz did all these things in her own way, not asking anyone’s permission. Her life wasn’t easy, she was often skint, but she was free and she loved it. She also loved Lee Arnold, but at a distance.

Eventually it was Mumtaz who spoke.

‘Lee, I’m busy. I want to get Bernie Bennett’s case kicked 36off, which means I have to work out who may and who may not be able to help me. The Jewish community in this part of London is small now and—’

‘Vi,’ Lee said. ‘Her mum was Jewish, speak to Vi.’

Mumtaz had thought about contacting ex-Inspector Violet Collins. Now retired from the Met, Vi had been Tony Bracci’s old boss and, for many years, Lee Arnold’s lover. Consequently, for Mumtaz to contact Vi had always been a bit problematic. But in spite of this, it was a good idea. Although she hadn’t been brought up Jewish, Vi knew a lot of the old families who either still lived in the East End or in nearby Essex.

Mumtaz agreed she would call Vi and then said to Lee, ‘Go to the pub with Ezra and his dad.’

Then she put the phone down.

Bernie often walked home after work. It wasn’t far. The only problem was crossing the A13, which involved several sets of traffic lights, road islands and a lot of twitchy drivers. Also the Custom House end of Prince Regent Lane, near where Bernie lived, could be a bit dodgy at night. It wasn’t so much the kids hanging out round the chippy or the alkies peering through the window of the offie – it was those you couldn’t see that were the problem. Men mainly, hanging back from the street lights in side alleys, lurking down behind Jay’s General Store, talking in hushed voices, passing things to one another.

You didn’t dare look. If you did, if you were lucky, they’d just tell you to ‘mind your fucking business’. If you weren’t lucky, they’d accuse you of ‘disrespect’ and kick the shit out 37of you. So Bernie kept his head down, eyes to the ground as he made his way off Prince Regent Lane and into Shipman Road. As he passed the Arnolds’ house he could see that the kitchen light was on. But Rose was unlikely to still be up. That would be for her eldest boy, Roy. He’d died a while ago, but Rose still kept a light on for him. An alcoholic, like his father, Roy Arnold would have been Bernie’s age, although no one would ever have guessed it. Unlike his younger brother Lee, Roy had always had a face like a smacked arse. Rail thin, he’d had a massive drinker’s hooter and had been beginning to turn yellow when he died. The only consolation for Rose was that now Roy was dead, no one smashed her place up any more. It was also said that his brother had helped put an end to all that too. When Roy had threatened their mother, Lee had given him a good hiding. Kicked the shit out of him.

Bernie took his door key out of his pocket and opened his front gate. Usually when he was on late shift, he made himself something to eat when he got home. But this time he was too knackered to think about food. There had been a lot of blood on the floor in A&E this evening, and also talking to that private investigator had taken it out of him. Just off to bed for him. Bernie went to put the key in the door, but found that he couldn’t. Because it was already open.