4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

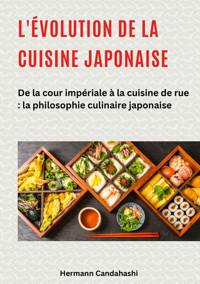

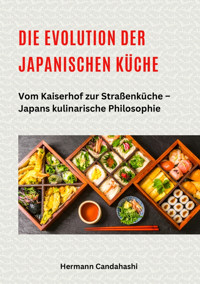

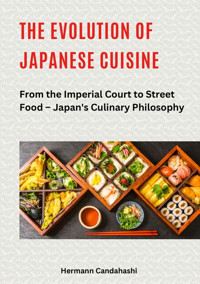

Discover the fascinating philosophy of Japanese cuisine – in all its depth, history, and diversity! Immerse yourself in the unique culinary journey "The Evolution of Japanese Cuisine – From the Imperial Court to Street Food – Japan's Culinary Philosophy," a comprehensive reference work on the development of Japanese culinary culture from early imperial banquets to modern street food on the bustling streets of Tokyo and Osaka. This exceptional book by renowned author Hermann Candahashi combines popular scientific analysis, cultural depth, and gripping storytelling in a fascinating blend that will delight history buffs, culinary enthusiasts, Japan fans, and specialist readers alike. From the influences of Zen Buddhism to the disciplined culinary culture of the samurai to the Western influences of the Meiji period – here you will learn how taste, philosophy, and aesthetics have evolved in Japan over the centuries. What makes this book special: - A unique look at the historical roots of Japanese cuisine - In-depth information on regional specialties from Hokkaido to Okinawa - Exciting insights into the significance of shojin ryori, kaiseki, and sushi - Presented in an understandable way for laypeople, yet in-depth for experts - Ideal for gourmets, Japanologists, travelers, food bloggers, and professional chefs Learn why Japanese cuisine is among the most renowned in the world today – and how deep-rooted traditions, religious influences, regional peculiarities, and historical upheavals continue to shape it today. A must-read for anyone who wants to know: What makes Japanese cuisine so unique – and what can we learn from it? With the help of this multifaceted work, enter a world full of enjoyment, knowledge, and cultural depth – for your library, your kitchen, or your next adventure in Japan!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 427

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

The Evolution of Japanese Cuisine –

From the Imperial Court to Street Food – Japan's Culinary Philosophy

© 2025 Hermann Candahashi

Druck und Distribution im Auftrag des Autors:

tredition GmbH, Heinz-Beusen-Stieg 5, 22926 Ahrensburg, Germany

Das Werk, einschließlich seiner Teile, ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Für die Inhalte ist der Autor verantwortlich. Jede Verwertung ist ohne seine Zustimmung unzulässig. Die Publikation und Verbreitung erfolgen im Auftrag des Autors, zu erreichen unter: tredition GmbH, Abteilung "Impressumservice", Heinz-Beusen-Stieg 5, 22926 Ahrensburg, Deutschland

Kontaktadresse nach EU-Produktsicherheitsverordnung: [email protected]

The Evolution of Japanese Cuisine

From the Imperial Court to Street Food – Japan's Culinary Philosophy

Chapters:

Foreword

Origins and early influences

The Samurai Era: Simplicity and Discipline in the Kitchen

The influence of Buddhism and vegetarian cuisine

Portuguese and European influences in the 16th century

The Arrival of the Portuguese: A Historic Turning Point

Culinary Transformations: New Techniques and Dishes

Social Dimensions of Culinary Exchange

Long-term effects and culinary legacy

The Edo Period: The Birth of Modern Japanese Cuisine

The role of the emperor and the imperial court

The Meiji Restoration and Western Influences

Regionality and diversity - culinary island hopping

Hokkaido – The Harsh but Rich Cuisine of the North

Tohoku – Traditional Flavors of the Inland

Kanto – Modern and Cosmopolitan Cuisine

Kansai – The Origin of Many Culinary Masterpieces

Chugoku and Shikoku – Authentic Regional Specialties

Kyushu and Okinawa – The Exotic Flavors of the South

The post-war period: scarcity, change and innovation

Sushi: From street food to global phenomenon

The Birth of Sushi

The Art of Sushi: Craft and Philosophy

Sushi Conquers the World: Global Expansion

The Sushi Economy: Markets, Trade, and Sustainability

Sushi and Culture: Identity, Status, and Pop Culture

Washoku: UNESCO World Heritage and Culinary Heritage

Modern fusion cuisine and globalization

The Fundamentals of Traditional Japanese Cuisine

The First Encounters: Western Influences in Japan

Japanese Cuisine Conquers the West

The Evolution of Modern Fusion Cuisine

The Social and Cultural Significance of Japanese Fusion Cuisine

The Future of Japanese Cuisine in a Global World

The future of Japanese cuisine

Japanese Cuisine in Transition - A Personal Summary

Demographic Change and Its Culinary Consequences

Also published by me:

Sake: The art of Japanese rice wine - The culture of the Japanese national drink

Japanese ceramics: From Raku to Kutani - A journey through the world of Japanese pottery

The Kimono: The Soul of Japanese Fashion and Iden-tity - A Journey through Japan's Textile Art History

Foreword

Japanese cuisine has a quiet power. It doesn't shout, it doesn't posturing loudly; it comes with restraint, with precision, with respect. And the more I delved into it, the more I realized: it's not just a form of food consumption; it's philosophy, history, spirituality, and aesthetics all rolled into one. Every meal tells a story. Every taste has a past.

This book arose from a deep fascination with how food can be an expression of culture, identity, and the spirit of the times. Japanese cuisine is a particularly impressive example of this. It has evolved over centuries, experienced upheavals, wars, isolation, and globalization—and has always retained its soul. Or rather, it has continually reinvented itself while preserving its essence.

The journey begins in the Jomon period, an era when people still lived in close symbiosis with nature. They gathered chestnuts, fished in the sea, and cooked in crudely shaped clay pots over an open fire. What initially seems archaic already contains the seeds of the attitude that would later form the backbone of Japanese cuisine: respect for what nature provides and a strong sense of seasonality.

Later, in the Yayoi period, rice becomes a cultural constant. A grain becomes currency, a sacrifice, a symbol of life itself. Buddhism then brings not only a religious worldview, but also new eating habits. The idea of purity, abstinence, and mindfulness also manifests itself on the plate. Vegetarian cooking traditions emerge that remain deeply rooted in the consciousness of many Japanese to this day.

And then: the courtly Heian period, in which cuisine is elevated to an art form. Meals are no longer merely functional, but a reflection of social order, a vehicle of symbolism, an instrument of representation. One doesn't just eat, one celebrates. And yet the focus always remains on the essential – it's never about excess, but about balance.

A leap forward to the Edo period shows how the urban population suddenly created its own culinary cosmos. Street food was born. Sushi became portable, tempura a quick treat, ramen a comfort food for the masses. And yet: the precision with which even the simplest dishes were prepared, the artistry, and the artisanal ethos remained intact. Street cuisine is no less venerable than that of the palaces.

Western influences also left their mark. Contact with Portugal in the 16th century brought not only tempura batter, but also sugar and new techniques. During the Meiji period, Japan continued to open up, absorbing Western ideas and integrating them—without abandoning its identity. This gave rise to dishes like tonkatsu and omurice, hybrid forms that could hardly be more Japanese. They demonstrate that this cuisine is not a static relic, but a living system, open to change.

What fascinates me time and again is Japanese cuisine's ability to unite opposites: austerity and playfulness, depth and simplicity, tradition and innovation. A kaiseki menu, composed like a poem, embodies this philosophy as much as a steaming bowl of ramen on a rainy evening in Osaka.

The global spread of Japanese cuisine in recent decades is a story in itself. Sushi bars all over the world, matcha lattes in coffee shops, bento boxes on supermarket shelves. But with popularity came simplification. Much has been stripped down, standardized, and adapted to the Western palate. That's why it's all the more important to look beneath the surface, rediscover the original spirit, and tell the stories behind the dishes.

This book isn't a pure cultural history, a recipe book, or a travel documentary—and yet it contains a little bit of everything. It's an attempt not just to describe Japanese cuisine, but to understand it. And it's an attempt to invite the reader to discover with me what makes this cuisine so unique. I spoke with chefs, housewives, monks, mothers, and grandfathers. I ate in small izakayas and kaiseki restaurants. I browsed markets and peered into the pots in temple kitchens. I tried to taste what time is, what silence is, what change is.

In doing so, I realized: Eating in Japan means becoming part of a heritage. It means performing a ritual that is greater than oneself. It means connecting—with nature, with history, with the present.

I hope that this book not only informs, but also touches. That it opens a window into a world where food is more than function. A world where a piece of pickled radish tells just as much of a story as an artfully arranged sashimi.

A world where the invisible becomes palatable. When you read this book, take your time. Let the images emerge. Taste with your mind, understand with your palate. And maybe, just maybe, you'll see the next piece of sushi with different eyes afterward.

Because it's this different way of seeing, this different way of perceiving, that makes Japanese cuisine so special. At first, it seems quiet, almost inconspicuous. But beneath this surface lies a deep web of symbolism, technique, ritual, and history. You don't have to speak Japanese to understand the meaning of a bowl of steaming miso soup on a cold winter morning. You don't have to have dined at the imperial court to sense that a kaiseki menu is more than just a sequence of courses. You just have to be willing to listen, taste, and look—with an open mind and genuine curiosity.

A central theme of this book is therefore the concept of mindfulness. Mindfulness not only in the sense of spiritual practice, but as a cultural constant that resonates in all aspects of Japanese cuisine. Whether in the selection of ingredients, the combination of flavors, the presentation, or the consumption – this deep, almost meditative relationship to what food is is evident everywhere. Food is not a consumer good, but an encounter. An encounter with nature, with the cycle of the year, with the hands that prepare it, with oneself.

Perhaps this is precisely what fascinates us in the West about Japanese cuisine. In a world where we have often lost touch with our diet, where meals are consumed in passing, in front of screens, on the go, while standing, it offers an alternative. A return to consciousness. Not as a dogma, but as an invitation.

Of course, Japanese cuisine has also changed. Globalization, urbanization, technological developments – all of this has left its mark. And yet, the core remains intact to this day: the principle of harmony, seasonality, the balance between flavor, color, texture, and temperature. These principles run like a thread through centuries of culinary history.

A particularly striking example of this is the concept of Ichiju-Sansai – "one soup, three side dishes." It is more than a formula for a balanced meal. It is an expression of a way of life. Nothing is superfluous, nothing is missing. The components complement each other, they respect each other, they subordinate themselves to the whole. It is this attitude that is also reflected in larger culinary concepts such as Kaiseki or Shojin Ryori.

And it is this attitude that is reflected in the small details of everyday life. In the way an onigiri is shaped. In the care with which bento boxes are filled. In the tranquility of a tea ritual. Or in the silent gesture with which one says before eating: "Itadakimasu" – "I humbly accept." A gesture of gratitude for everything that made this meal possible.

I firmly believe that we can learn a lot from this attitude. Not by trying to imitate Japanese cuisine, but by understanding its spirit. By asking: What truly nourishes us? What does it take for food to become more than just a calorie intake? How can we reconnect – with our food, with our environment, with ourselves?

This book aims to provide answers to these questions. It aims to show how Japanese cuisine has developed over millennia, the influences that have shaped it, and the role that religion, politics, society, and nature play in this. I'm aware that this is an ambitious undertaking. Japanese cuisine is a vast field, full of nuances, contradictions, and surprises. I can't depict it completely. But I can open a window. Provide a glimpse. Convey a taste. And if I succeed in inspiring you as a reader a little, arousing your curiosity, perhaps even changing you a little – then this book will have fulfilled its purpose.

In the end, perhaps that's exactly what Japanese cuisine teaches us: That it's not about the destination, but about the journey. Not about the grand spectacle, but about the moment. Not about perfection, but about presence. And therein lies its quiet, powerful beauty.

Origins and early influences

Anyone who wants to understand Japanese cuisine must go back a long way—not only in history, but also in thought. Its roots go deeper than many assume, back to a time when the term "Japan" did not yet denote a national identity, but rather a geographical area inhabited by people whose lives existed in close symbiosis with the cycles of nature. These early societies, long before the emergence of state structures, laid the foundations for what we now understand as Japanese culinary culture with their daily routines, techniques, rituals, and ways of life. The search for traces begins in the Jomon period, which dates from approximately 14,000 BC to 300 BC.

The Jomon people lived in small groups, hunted game, gathered edible plants, fished in the rich coastal waters and rivers, and cooked their food in crudely formed but remarkably durable clay vessels heated over an open fire. The famous Jomon pottery, often artfully decorated, is considered not only cultural artifacts but also early evidence of conscious preparation techniques. Chestnuts, acorns, roots, and fish were cooked and possibly fermented in these vessels—a process that not only contributed to preservation but also enhanced flavor. This already reveals a central feature of later Japanese cuisine: the ability to make much from little, through patience, attentiveness, and a deep understanding of natural processes.

With the transition to the Yayoi period, beginning around 300 BC, a decisive change began. The people of this period, presumably migrants from present-day Korea or China, brought with them new technologies, including wet rice cultivation. Thus, rice became not only the main source of food but also a cultural center. Rice was more than a food. It became the standard of social order, the basis of ritual practices, and a symbol of prosperity. Settlements formed around fields, and social life increasingly organized itself around the seasons, whose significance now penetrated even more strongly into culinary consciousness. Rice growers live with the rhythm of water, rain, and sun. Nature was perceived not only as a habitat, but as a partner, sometimes also as an adversary, and in any case as a force with which one had to come to terms.

With this settled lifestyle came the refinement of techniques. Cooking, smoking, drying, and fermentation all developed further. Fermentation, in particular, would establish itself as a culinary and cultural constant in Japan. The need to preserve food gave rise to products such as miso paste, soy sauce, and narezushi—an early form of sushi in which fish was fermented with rice to preserve it for months. The sense of taste, trained by such intense, complex flavors, formed a cultural palate that differed significantly from the Western sensibility. Umami, the so-called fifth taste, was not discovered in this process – it was always there, a part of everyday life, without being named.

The next impetus came with the spread of Buddhism from China via Korea to Japan, beginning in the 6th century AD. This influence was not merely religious or philosophical in nature, but had a profound impact on eating habits. The teachings of moderation, respect for all living beings, and the pursuit of inner purity led to a reduction in meat consumption, especially of four-legged animals. The killing of animals was viewed as karmically negative, which led to the rise of vegetarian dishes. Shojin Ryori, Buddhist temple cuisine, emerged from this idea and continues to influence the concept of how simplicity, balance, and spirituality can be expressed in a dish. This cuisine was not ascetic in the sense of abstaining from flavor – rather, it was permeated by a deep sensitivity to textures, colors, temperature conditions, and seasonal nuances.

Shojin Ryori is far more than a vegetarian cooking style—it is an expression of a way of life, a spiritual path, and a deep-rooted connection between nutrition, ethics, and mindfulness. The term is composed of three characters: "Sho" means purity or striving, "Jin" stands for devotion or discipline, and "Ryori" is the Japanese word for cuisine or cooking. Literally translated, Shojin Ryori could be called "cuisine of the striving spirit" or "cuisine of devotion." In practice, it describes the traditional vegetarian cuisine of Buddhist monks in Japan, particularly those of the Zen schools.

But Shojin Ryori goes far beyond simply being a vegetarian. It's not about abstinence, but rather a focus – on the essential, on the seasonal, on what nature is ready to provide at a particular moment. Neither garlic nor onions nor other "irritating" ingredients are used, as according to Buddhist teachings, these could upset the mind and disrupt meditation. Highly processed products and artificial flavors are also out of the question.

Instead, typical Shojin Ryori ingredients include:

- Tofu and other soy products such as yuba (tofu skin) or okara (tofu pulp)

- Beans and lentils

- Seasonal vegetables, preferably locally grown and left in their natural form

- Roots such as lotus root, radish (daikon), carrots, and gobo (burdock root)

- Seaweed, especially kombu and wakame

- Mushrooms such as shiitake or enoki, which can replace animal products due to their texture and umami qualities

- Sesame, nuts, and seeds

- Rice, especially brown rice, often used as a staple food

- Miso, soy sauce, mirin, and other traditional plant-based seasonings

A key principle of Shojin Ryori is the balance of the five flavors—sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami—and the five colors—white, black, red, green, and yellow. Added to this are the five preparation methods—raw, boiled, fried, steamed, and deep-fried—which are often combined in simple ways. The goal is to achieve harmony and variety with minimal resources.

The preparation itself is considered part of the meditative path. The kitchen of a Zen temple is not just a place of work, but a space for practice. The tenzo, or chief cook, is traditionally considered one of the most important monks. His position is held in great respect, as he is responsible for the physical and spiritual well-being of all practitioners. The famous work "Tenzo Kyokun" (Instructions for the Temple Cook) by the 13th-century Zen master Dogen explains how deeply spirituality, cooking, and consciousness are intertwined. In it, Dogen writes that cutting a vegetable must be done with the same mindfulness as sitting in zazen (meditation). Every action counts. Every moment carries meaning.

The serving of the food also follows a ritual: Usually, three to five small bowls are offered, carefully arranged, without overloading. This, too, reflects the attitude of receiving rather than consuming. Food is not devoured, but rather observed, appreciated, and valued – as a gift, as a process, as a reflection of the season. The meal often begins with a brief expression of thanks (“Itadakimasu”) and ends with the equally respectful “Gochisousama deshita,” which essentially means “Thank you for the delicious meal,” but also expresses gratitude to everyone involved – to the cook, to nature, to the effort behind every bite.

A classic Shojin Ryori dish is “Kenchinjiru,” a clear vegetable soup based on kombu, containing root vegetables and tofu cubes. Or “Goma-dofu,” a “tofu” made from sesame and arrowroot starch, whose texture is more like pudding than tofu. Such dishes appear simple at first glance, but develop a complex, surprising flavor in the mouth – calm yet deep. Entirely in the spirit of Zen.

Shojin Ryori has also become known outside of monasteries in recent decades, particularly through the rediscovery of traditional, sustainable, and healthy lifestyles. In cities like Kyoto or Kamakura, you can now sample authentic shojin dishes in specialized restaurants. But here, too, anyone who truly embraces this cuisine must be willing to slow down, refine their flavors, and embrace stillness. Shojin ryori is not a trend. It is a practice – with the knife, with the bowl, with oneself.

In summary, shojin ryori is not just Japanese veggie food. It is a living tradition, a lived ethic, a philosophy on the plate. It teaches us to cook with respect, eat mindfully, and live with gratitude. In a world often characterized by excess and hecticness, it offers an alternative: humble, beautiful, and profound.

Interestingly, this religiously motivated abstinence did not mean a complete renunciation of meat or animal products. Rather, alternative forms of protein consumption were cultivated: fish, seafood, seaweed, tofu, and bean products came to the fore. This variety of ingredients was not chosen at random, but rather developed from the geographical reality of the Japanese archipelago. The sea was omnipresent, and fish-rich waters surrounded every village. This gave rise to a seafood cuisine that relied not on abundance, but on quality, freshness, and precision in preparation.

However, the Japanese peninsula was never completely isolated, even though national mythology often cultivated this idea. Early contacts with the Asian mainland, particularly via trade routes to China and Korea, led to the adoption of numerous elements that are now considered "typically Japanese." Eating with chopsticks, steam cooking, the use of soy sauce, tea, and even the concept of menu sequences—all of these originated outside the islands and were not only adopted in Japan, but adapted, refined, and transformed into something unique. The pattern evident here will continue throughout Japan's culinary history: absorb, internalize, transform. Never simply copy.

Tea is an excellent example of this. Although it originated in China, it became the bearer of its own philosophy in Japan. The influence of Zen Buddhism transformed tea preparation into an art form and drinking it into a spiritual act. Tea culture created a space in which culinary arts were not merely functional but also meaningful.

From its very beginning, Japanese cuisine was thus an interplay between local resources, religious ideas, and foreign influences. These forces didn't work side by side, but rather intertwined.

It would be too easy to consider them separately. Rather, they permeated each other, forming a cultural code that was not transmitted in written recipes, but in gestures, in techniques, in everyday observation. Young people learned to cook not from books, but by watching, by participating, and by repetition. Cooking was a physical practice, a form of learning by doing, of remembering through action.

Another influence on early Japanese cuisine that should not be underestimated was nature itself—not only in terms of the availability of ingredients, but also as an aesthetic principle. The seasons became coordinates of culinary identity. Spring represented delicate bitterness, summer freshness, autumn depth, and winter tranquility. This seasonal logic permeated not only the menu, but also the way food was presented, the dishes, and even the architecture of the spaces in which food was eaten. Culinary arts were never isolated, but always embedded in a larger structure of environment, aesthetics, spirituality, and community.

When asking about the origins of Japanese cuisine, one must look beyond the juxtaposition of ingredients or dishes. One must recognize that it is rooted in a system of meanings in which food not only nourishes but also guides. The early influences—whether from the forests of the Jomon period, the fields of the Yayoi culture, or the monasteries of the early Buddhist schools—were not merely historical developments. They were fundamental building blocks of a worldview that translated into taste.

And so, Japanese cuisine today is not the result of modern trends or culinary fads, but the continuation of a way of thinking that began millennia ago. It is the echo of those first fireplaces, those first bundles of rice, those first quiet meals before a stone altar or in a bamboo grove. It is the memory of a culture that is revived with every bite.

The Heian Period: Culinary Art as an Art Form

The Heian period, which lasted from 794 to 1185 AD, was an era of extraordinary cultural flourishing in Japanese history. During this period, named after the then capital city of Heian-kyo – present-day Kyoto – court culture achieved a level of sophistication and elegance that was evident in almost all areas of life, but especially in the world of aesthetics. Literature, poetry, fashion, architecture, and even cuisine were expressions of a social elite that saw itself as a cosmic order. Food in the Heian imperial court was not just sustenance – it was staging, symbolism, a play of form and color. To understand the culinary culture of this period, one must abandon the idea that cuisine was purely functional at this time. Rather, it was a part of the ceremonial, imbued with poetic meaning and ritual structure.

At the imperial court, every detail of life was considered a potential vehicle for aesthetic perfection. This attitude also influenced the way meals were prepared, presented, and enjoyed. The aristocratic class, especially the Fujiwara family, which exerted great influence on the politics and culture of the time, saw itself as the bearers of an almost divine way of life. Culinary arts became a reflection of this way of life. It was not abundance that counted, but refinement, not satiety, but the play with suggestion and restraint.

The court cuisine of the Heian period, often referred to as "yusoku ryori"—which means "noble cuisine"—was deeply interwoven with court rituals. Meals were served according to established protocols that not only served physical pleasure but also expressed social hierarchies. The number of dishes, the selection of ingredients, the placement of bowls—all of this followed complex rules whose purpose was not solely to eat, but to demonstrate order, harmony, and belonging.

The menus often consisted of numerous small dishes served on lacquer trays. Fish, seaweed, wild vegetables, and rice dominated the offerings. Due to the influence of Buddhism, meat from four-legged animals was rare and was considered rude or barbaric anyway. Instead, the focus was on dishes that emphasized the natural – the delicate bitterness of young bamboo shoots, the umami of dried shiitake, the fleeting sweetness of fresh chestnuts. Fermented products also played a significant role, such as miso paste or various forms of pickled vegetables. These ingredients were not merely foodstuffs, but carriers of meaning: the sour taste could express sorrow, the salty and smoky flavor of fermented fish perhaps a melancholic depth. Food was codified, a language.

Just as important as the taste was the presentation. The color of the food was carefully matched to the season and the occasion. Light green in spring, deep red and gold in autumn, pale white in winter – the plate was the stage, the food the performer. The choice of vessels was by no means random either. Porcelain, ceramics, lacquer, and bamboo vessels were carefully combined, sometimes deliberately irregularly, to celebrate the idea of "wabi"—beauty in imperfection. This philosophy, which would later flourish in the tea ceremony, was already essentially established in the Heian period: the simple as profound, the inconspicuous as the bearer of truth.

The cultural significance of food was also evident in the literature of the time. In the famous court lady Sei Shonagon and her work "Makura no Soshi"—The Pillow Book—there are numerous passages in which food is not only mentioned but celebrated. Her descriptions of small dishes delicately arranged on dark lacquer, the scent of freshly roasted rice grains, or the clarity of cold tea testify to a deep sensitivity. In the world-famous story "Genji Monogatari" by Murasaki Shikibu, banquets, feasts, and small private dining scenes are depicted with such meticulousness that one almost feels as if one is tasting the food itself. Literature and culinary arts merged into an aesthetic continuum—both expressions of a world in which form and content were inextricably linked.

This profound connection between art and food also led to the development of specific dining rituals. The so-called "gozen" was a form of courtly banquet in which several courses were served in specific arrangements. Attention was paid not only to the food itself, but to the entire setting: the space, the lighting, the tablecloth, the movement of the guests. The act of eating became a choreography, a presentation, almost a performance. The cook was not a service provider, but part of an artistic ensemble.

Interestingly, parallel to the courtly ideal, peasant and folk diets developed along completely different lines. While the nobility philosophized over poetically charged menus, the rural population subsisted on millet, sweet potatoes, vegetables from their own gardens, wild herbs, and fish. This gap, however, did not lead to alienation, but rather to a dialectical tension that would later feed many facets of Japanese cuisine. Aristocratic aesthetics encountered the robust techniques of the peasant world—a process that would last centuries but would decisively shape Japan's culinary diversity.

Last but not least, the Heian period was also an era of retreat, of introspection. Political power increasingly lay with the imperial court, but at the same time, the first military structures were forming, which would later lead to the rise of the samurai. During this interim period, a lifestyle flourished that could perhaps be described as contemplative luxury. Eating became part of this attitude to life—a moment of slowing down, of turning away from the world, of concentrating on the essential. Preparing a travel bowl could be as meaningful as writing a poem.

This attitude—that the small reflects the large, that an entire world can be contained in the preparation of a meal—is one of the legacies of the Heian period, one that continues to resonate in Japanese cuisine to this day. The idea that every meal is an act of appreciation—of nature, of community, of the moment—has its roots right here. And so it can be said: The Heian period not only shaped Japanese cuisine, but poeticized it. It transformed food into an art form, the echo of which can still be felt in a simple rice ball, if it was formed with the same care as it once was at the court of the imperial city of Heian.

While the aristocratic upper class in Heian-kyo elevated their meals to an almost spiritual act of aesthetics, a completely different culinary reality existed beyond the palace walls. The common people, consisting of farmers, fishermen, artisans, and migrant workers, lived in a world where food was primarily a means of survival. Yet even in this pragmatic diet, deep-rooted traditions, social rituals, and a form of culinary creativity can be discerned that is often overlooked. The cuisine of the common people was simple but not monotonous—it was earthy, seasonal, nutrient-conscious, and characterized by a high degree of adaptability.

Rice was also considered a central food for the rural population, but access to polished white rice was limited. The majority ate unpolished brown rice or mixed it with other grains such as millet (awa), barley (mugi), or buckwheat (soba). These mixed forms were not only cheaper to produce but also more robust in their storage. Especially in times of poor harvests, so-called "additives" were used—pulses, sweet potatoes, or chestnuts, which were mixed with the rice to increase its volume.

Vegetables played a central role in peasant diets, with regional and seasonal varieties being used primarily. Since there was no refrigeration or modern preservation methods, techniques such as pickling in salt (shiozuke), in bran (nukazuke), or drying mushrooms, squash, and wild vegetables developed early on. These methods not only ensured food supply during the winter months but also altered the flavor and texture of the ingredients in interesting ways. The consumption of pickled daikon radish or fermented plums (umeboshi) was just as common in peasant households as the preparation of simple soups based on seaweed or fish broth.

An important source of protein was fish—both freshwater fish from rivers and streams and marine fish in coastal regions. In rural areas, it was common to dry or ferment fish, which not only extended its shelf life but also produced intense, complex flavors. Particularly popular was the so-called "narezushi" – an early form of today's sushi – in which fish was fermented with cooked rice and salt. The rice originally served only as a fermentation agent and was not eaten. It was only much later that this developed into the now well-known "Edomae sushi."

Meat played an ambivalent role in peasant cuisine. Although the consumption of meat was officially frowned upon by Buddhism, in practice, game – especially wild boar, deer, and birds – were consumed in some regions, especially in remote mountainous areas where religious rules were more loosely interpreted. However, this practice was usually carried out in secret and was rarely documented in official sources. The killing of an animal often had a ritual character and was associated with respect for life, with every edible component being utilized.

The fireplace played an often overlooked but central role in the peasant household. The "irori," a sunken hearth in the center of the room, was not only a cooking area, but also a place of warmth, communication, and social closeness. Iron pots hung over the open fire, in which rice porridge, stews, or vegetable dishes were prepared. These were often simple dishes—rice with root vegetables, a clear broth with spring onions, or a porridge made from fermented soybean paste—but the way they were prepared and the shared meals strengthened family and village ties.

Women's role in the peasant kitchen was central. They were responsible not only for daily cooking, but also for preserving food, cultivating small home gardens, and gathering wild plants. Many of these tasks required a high level of knowledge of natural cycles, medicinal plants, and fermentation processes. For example, "koji," the noble mold necessary for the production of miso, soy sauce, and sake, was often cultivated and cared for by women. These activities were not documented in writing but passed down orally through generations, demonstrating that the local population's culinary knowledge, while invisible, was by no means less complex than that of the courtly world.

Festivals, ceremonies, and the changing seasons also provided occasions for special dishes in rural life. Rice cakes (mochi) were prepared at New Year's, and seasonal ingredients such as young bamboo shoots, chestnuts, or new varieties of rice played a symbolic role in spring and autumn festivals. The preparation of these dishes was often associated with communal rituals in which neighbors and relatives gathered to pound mochi, ferment soybeans, or prepare canned vegetables for the winter. These communal cooking and eating rituals strengthened not only the social fabric but also the region's culinary heritage.

Another fascinating aspect of rural cuisine was improvisational creativity. In the absence of abundance, people developed a fine art of substitution. If soy sauce was unavailable, it was replaced with fermented fish sauce. When grain ran out, acorns were boiled and made into porridge. This flexibility was less an expression of necessity than a sign of a deep connection to the environment—a knowledge of what was there and how to harness it.

This cuisine was neither glamorous nor luxurious, nor aesthetically composed like courtly dishes. Yet it was profoundly sustainable, down-to-earth, and above all, vibrant. While the nobility sought to elevate themselves above nature through art, the rural population lived in and with nature. This proximity to the seasons, to the rhythm of the day, to the available resources shaped peasant cuisine in a way that still resonates in everyday Japanese cuisine today. Many dishes that are considered classics today—such as miso soup, pickled cucumbers, or simple rice balls with umeboshi—originated not in palaces, but in village huts.

Ironically, with the growing popularity of Zen Buddhist shojin cuisine, a cultural convergence later took place: the abstinence from meat, the focus on regional ingredients, the simplicity of preparation—all of these were principles that had long been practiced in rural cuisine before they were transfigured spiritually. Thus, in the development of Japanese cuisine, two worlds that at first glance seemed incompatible met: the world of aesthetics and that of necessity, art and everyday knowledge, the golden palace and the mud hut.

This dialectical relationship continues to shape Japanese cuisine to this day. And the Heian period in particular was a crystallization point at which these trends first manifested themselves in a culturally conscious way. While in the palace, rice was polished, fish was filleted, and vegetables were cut into flowery shapes, in the countryside, simple baskets of sweet potatoes roasted over an open fire. Both acts were significant—one as an expression of art, the other as an expression of life.

The culinary practices of the common people during the Heian period were not simply an expression of poverty or deprivation, but a complex system of survival, adaptation, and cultural self-affirmation. In a time when access to education, political influence, or property was severely limited, cooking became a form of lived intelligence, a collective memory transmitted through taste, smell, and habit. Peasant cooking was the daily ritual that determined the rhythm of life—from the first steaming of rice at dawn to the last spoonful of warming broth at nightfall.

For a long time, however, this lived culinary culture of the common people was not recognized as part of official history. Written sources focused on the court, on ceremonies and banquets, on aesthetics and etiquette. Yet precisely where history remained silent, real life flourished. The cuisine of the Heian period consisted not only of opulent imperial menus, but also of rice porridge in the morning, pickled turnips in the evening, and the daily effort to make something nourishing from what little was available.

In a certain sense, this cuisine was even the origin of the culinary philosophy that was later celebrated as typically Japanese: reduction to the essentials, respect for ingredients, cooking with the rhythm of nature, awareness of time, patience, and transformation. Peasant cuisine can thus be considered the silent foundation upon which the sophisticated developments of later eras were built. Its principles – simplicity, mindfulness, seasonality, and resource conservation – are more relevant today than ever and are experiencing a belated but well-deserved recognition in modern movements such as Washoku, Slow Food, and the return to regional cuisine.

At the end of the Heian period, towards the end of the 12th century, social and political structures in Japan began to change drastically. With the rise of the samurai class and the growing influence of Buddhist monasteries, new impulses entered Japanese culinary culture, which would continue to evolve and refine. Yet the influence of peasant cuisine persisted—often unnoticed, but deeply woven into the country's cultural memory. For it was never merely a necessity. It was knowledge, habit, community—and perhaps more than anything else: home.

Thus, a look at Japanese cuisine during the Heian period does not end with an image of scarcity, but with an awareness of a quiet yet significant cultural achievement. In the smoke-blackened huts of the rural population, not only meals were prepared—there were values, memories, and identities cooked, braised, pickled, and passed on. A cuisine without wealth, but with an immeasurable treasure of experience. A cuisine that has endured through the centuries—not through splendor, but through depth.

The Samurai Era: Simplicity and Discipline in the Kitchen

The history of Japanese cuisine is also a reflection of social upheavals, cultural ideals, and spiritual worldviews. In hardly any other era is this more evident than in the era of the samurai, that long and formative period from the late 12th century to the mid-19th century, in which military virtues, ascetic discipline, and social order determined the fabric of Japanese society. The samurai, those legendary warriors with the code of Bushido, not only influenced politics, art, and morality—they also left a deep mark on the culinary world.

With the transition from the courtly Heian culture to the rule of the warrior nobility, particularly under the Kamakura and later the Tokugawa shogunate, the structure of Japanese society changed fundamentally. The decadent, symbolically over-laden cuisine of the imperial court gave way to a new form of eating: functional, simple, and imbued with a philosophy of moderation. For the samurai, the focus was not on enjoyment, but on physical and mental preparation for battle, the training of the will, and the maintenance of inner order. Food became a means of self-discipline.

A samurai's daily meal was neither opulent nor festive. It usually consisted of simple ingredients: steamed rice, pickled vegetables, miso soup, and occasionally some fish or tofu. Meat remained rare and, in many regions, frowned upon or forbidden—both for religious reasons and cultural custom. The simplicity of these dishes, however, was not a form of deprivation, but rather an expression of an inner attitude. The idea of strengthening the body through food, rather than weakening it, was deeply connected to the principles of Zen Buddhism, which was gaining increasing influence during this period.

Zen Buddhism, which had reached Japan via China, found fertile ground in the samurai class. His ideals of stillness, concentration, self-control, and the search for truth through direct experience complemented the values of Bushido. This gave rise to a culinary practice that was unique in both its simplicity and its spirit. Shojin Ryori, a Buddhist vegetarian cuisine, was not only practiced in monasteries but also shaped the eating habits of many samurai, who adopted Zen principles in their private lives. No garlic, no onions, no animal products – instead, care, purity, and the pursuit of balance.

This form of nutrition required dedication, planning, and knowledge. Respect for the ingredients, precise cutting, precise steaming, and balanced seasoning became meditative acts. The kitchen was not a place of noise, but of silence. Preparing a meal was like drawing a sword: every movement had weight, every hand movement had meaning. In samurai homes, meals were often ritualized, often in silence, accompanied by a brief expression of thanks to nature and the hands that had prepared the food. Thus, the meal became a moment of reflection, a pause in the flow of everyday martial life.

At the same time, new ways of dealing with food also developed under the influence of Zen. The tea ceremony (chanoyu), which reached its full bloom during this period, was far more than a social event—it was a lived philosophy, an expression of inner attitude, in which small culinary accompaniments such as wagashi (Japanese sweets) or light meals (kaiseki) played a central role. The aesthetics of simplicity (wabi-sabi), the play with silence, space, and time—all of this fundamentally shaped the relationship to food.

But even outside the monasteries and samurai residences, everyday life remained characterized by simplicity. In the barracks and garrisons where lower-ranking samurai served, eating was a logistical act. Rice balls, dried fish, pickled vegetables—long-lasting, readily available foods dominated the menu. The ability to prepare nourishing meals with few resources was valued and taught during training. At the same time, eating together remained a social ritual: it strengthened camaraderie, disciplined behavior, and reflected military order.

It is noteworthy that during this period, the first culinary consciousness emerged, based on values such as purity, respect, moderation, and seasonality—concepts that continue to shape Japanese cuisine today. The idea that good food doesn't have to be expensive, but rather conscious; that the seasons should be respected; that waste should be avoided and nature should be thanked—all of this is deeply rooted in the samurai era.

Knowledge of the healing properties of certain foods, conscious fasting, and the ritual significance of food can also be traced back to this period.

During the long period of the Tokugawa period (1603–1868), when the country was largely pacified, the relationship to cuisine changed again. While the elite slowly turned to more indulgent forms of eating – especially in the cities – the ideals of the samurai persisted in rural areas and among conservative households. Reduction, concentration on the essentials, and the avoidance of excess: these were not just virtues of the warrior, but became part of a cultural identity.

The samurai era taught Japan that food is more than just satiety. It is an expression of attitude, a means of self-leadership, and a reflection of social order. Between the rice bowl and the miso bowl, an ethos was formed that lives on in Japanese kitchens to this day – whether in the careful arrangement of a bento, the respectful expression of thanks before a meal (itadakimasu), or the contemplative preparation of tea.

And so one can say: In an age characterized by swords and battles, in the simplicity, the reduced, the quiet, a power was found that reached deeper than the sound of steel – the power of discipline in the kitchen, born of the world of the samurai.

But let's delve deeper into the Tokugawa period. This period was not only a period of political stability and social order, but also a phase of culinary differentiation and cultural development that laid the foundation for many aspects of modern Japanese cuisine.

The Tokugawa period (also called the Edo period, 1603–1868) marked a profound change in everyday Japanese culture—especially with regard to food. After centuries of warfare, the Tokugawa shogunate brought political stability, a strong central government, and a clear social order. This calm not only allowed for economic growth but also a refinement of eating habits—especially in urban centers such as Edo (now Tokyo), Kyoto, and Osaka.

During this era, food was no longer viewed exclusively as a necessity or spiritual tool, but increasingly as a cultural expression, a social distinguishing mark, and even an aesthetic practice. While the nobility and higher samurai continued to enjoy simple, disciplined meals, a new urban food culture emerged in the cities—the cuisine of merchants, artisans, artists, and traders.

A central aspect of Tokugawa cuisine was the increasing variety of ingredients. Due to Japan's relative isolation from the outside world, local production intensified, regional specialties gained importance, and domestic trade flourished. Markets offered an impressive array of fresh vegetables, rice varieties, fish, fermented products such as soy sauce, miso, and umeboshi (pickled plums), and soon sugar, which became a sought-after commodity. Especially in Osaka, known as the "nation's kitchen," a lively trade in food from all parts of the country developed.

Rice remained the staple food and, during the Tokugawa period, also became a measure of economic power—taxes were levied in rice, and wages were based on rice. However, the preparation methods continued to differentiate: from simple steamed gohan to mixed rice (takikomi gohan) to rice balls (onigiri), rice cakes (mochi), and fermented versions.

Fish and seafood became a culinary signature during this period. The coastal regions supplied the cities with fresh produce, which was prepared in a variety of ways: grilled, dried, pickled, or raw. This is also where the development of the practices that would later lead to sushi culture began. Originally, sushi was a method of preserving fish with fermented rice (narezushi), but in urban Edo, this evolved into the now familiar nigiri sushi – faster, fresher, and tailored to the urban lifestyle.

Tempura also took on its familiar form during this period. Probably inspired by Portuguese missionaries in the 16th century, the frying technique was adapted and refined. The first street stalls emerged in the alleys of Edo, offering light, crispy bites of vegetables or fish – affordable, quick, and delicious.

Another typical dish was soba – buckwheat noodles served either hot in broth or cold with dipping sauce. The simplicity of the ingredients contrasted with the precision of the preparation. During the Tokugawa period, the art of noodle making was truly celebrated: dedicated specialty shops, specialized cutting techniques, and regional variations. Udon and later ramen (in an early form) also gained popularity.

Sweets experienced a resurgence in the Edo period, not least due to increased access to sugar. Wagashi—artfully shaped sweets made from rice flour, bean paste, chestnuts, or yams—increasingly became part of the tea ceremony, but also served as an elegant accompaniment to social gatherings or festivities. Their shapes often reflected the seasons and became an expression of refined aesthetics.

What particularly distinguished the food of this era was its increasing seasonality. A deep awareness developed that spring tasted of fresh bamboo shoots and young spinach, summer of cool noodles and watermelon, autumn of mushrooms and chestnuts, and winter of hot stews and pickled vegetables. This harmony with the seasons was not only valued, but actually cultivated – in the selection of ingredients, presentation, and even in the tableware.

At the same time, a social system of eating developed. The upper classes preferred refined kaiseki menus – multi-course, finely balanced meals that evolved from the tea ceremony. The urban middle class, on the other hand, created its own food culture: street stalls (yatai), inns (ryotei), snack bars, and the first specialized restaurants. Here, the diversity of Japanese cuisine became accessible to everyone, often with high standards of quality and great creativity.

In summary, the Tokugawa period was an era of culinary order and differentiation. It not only produced new dishes, but also a new awareness of food itself – as a social act, as an art form, as a reflection of one's own class and the times.

And although samurai discipline continued in many households, the cuisine simultaneously opened up to the playful, the beautiful, and the sensual.

At the end of the Tokugawa period, we are faced with a culinary panorama that impresses not only with its diversity and sophistication, but also with its cultural depth and social significance. This era, characterized by stability, isolation, and a strictly structured social structure, profoundly shaped the Japanese understanding of food and offers a crucial key to understanding today's Japanese cuisine.

What makes the Tokugawa period so unique is the simultaneous existence of constancy and change. On the one hand, the foundation of the diet remained unchanged: rice, vegetables, fermented products, and fish were the mainstays. The principles of simplicity, modesty, and respect for nature, as they emerged from Buddhist and Confucian influences, lived on especially in the homes of the samurai. There, food was not merely a necessity, but a reflection of inner discipline, moral stance, and spiritual conviction.

On the other hand, a new urban food culture emerged, characterized by creativity, enjoyment, and experimental curiosity. Flourishing trade between regions, the emergence of specialized culinary arts, and the increasing differentiation between everyday dishes and festive feasts led to a previously unknown diversity. From this mixture emerged many of the dishes that are now considered the epitome of Japanese cuisine worldwide: sushi, tempura, soba, kaiseki, and wagashi.

Also striking is the beginning of the institutionalization of food. Professions centered around cooking, with their own guilds and social roles emerging – from soba masters to tea masters. The first written culinary theories took shape. Cookbooks, restaurant guides, and even humorous stories about food became popular. Culinary arts increasingly became a part of popular culture – not just food, but a topic, a subject of conversation, even an object of art.

Another significant aspect of Tokugawa cuisine is the aesthetics associated with it. The way food was presented, the way bowls and plates were selected, and the way colors, textures, and shapes were combined expressed a deeply rooted ideal of harmony. Visual presentation became just as important as taste. The focus was not on ostentation, but on the subtle interplay of restraint and attention to detail – what is known in Japanese thought as "wabi-sabi": beauty in the imperfect, the simple, the transient.

This era also shaped a new sense of time in the way we deal with food. Seasonality became a maxim. The selection of dishes and ingredients was based not only on availability, but also on culturally codified ideas about what was appropriate at which time. Spring vegetables, summer fruits, autumn mushrooms, and winter root vegetables were not merely foodstuffs, but carriers of symbolism, emotion, and ritual. Thus, a culinary annual cycle emerged that reflected life itself.

Last but not least, the Tokugawa period also saw the birth of public gastronomy. What was once reserved for the upper classes – enjoying a cooked meal outside the home – now became possible for broader sections of the population. In the lively alleys of Edo and Osaka, along riverbanks and at temple complexes, a food culture grew that promoted mobility, communication, and community. Eating together became an act of participation in urban culture.

The chapter on the samurai era, and in particular the Tokugawa period, cannot be understood as a mere description of menus or methods of preparation. Rather, what emerges here is a cultural fabric in which food functions as a vehicle for values, identity, and worldview. The kitchen was both a mirror and a driving force of social processes. It served both as a means of discipline and development. It was an expression of status, but also a means of overcoming social barriers.

In retrospect, it becomes clear that samurai cuisine was not merely austere and ascetic—it was imbued with meaning. And the urban cuisine of the Tokugawa cities was not merely delicious—it was a cultural experimental ground, a place for playing with tradition and innovation.