0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

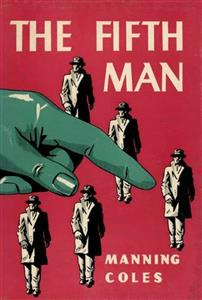

When five British prisoners escape from the Nazis, Tommy Hambledon is assigned to find out which one is a German double agent!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Fifth Man

by Manning Coles

First published in 1946

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

The Fifth Man

To entertain some idle moment

I

WHO COMES?

He came wavering down the lane in the gathering darkness; to the watchers in the shadow of the holly hedge he seemed to be not without his troubles, for his front light was flickering off and on and every time it failed him he wobbled violently.

“Not very expert, apparently,” said one of the watchers in a quiet voice. “Better stop him, Widgers.”

Constable Widgers stepped into the road and flashed his torch as a signal, adding, “Stop, please, sir.” This sudden intervention was too much for the cyclist who practically fell off, only remaining on his feet by an effort. “You startled me,” he said in an amused voice, “I nearly came a frightful crash and lost the most valuable part of my shopping. Who are you?”

“P.C. Widgers of Chiddon,” said the constable. “May I see your identity card, please?”

The constable’s torch illuminated a grossly fat man dressed in shabby flannel trousers with elastic bands round the ankles in place of unobtainable trouser-clips, a high-necked sweater with a cardigan over it and an old tweed jacket over that. He wore no hat; his bald head, surrounded by a coronet of greyish curls, looked not so much as though the hair was missing as that the accretion of tissue had pushed its way through its thatch. He had a fat good-tempered face, creased in the lines of frequent laughter, and a soft fruity voice with a chuckle in it. He propped his bicycle carefully against one substantial thigh and produced his identity card from his coat pocket.

“There you are, constable,” he said, and handed it over. The front wheel of his cycle swung round, he caught at the handlebars, and his lamp promptly went out.

“Confound the thing,” he said. “It’s been doing that ever since I had to light up, but I don’t think it need perform in front of the police. Uncalled-for. It goes on again if you hit it,” he added, giving the lamp a slap which had the effect desired. “The trouble is that I am by no means an expert rider, as you may have noticed, and every time I lean over the handlebars to give it a clout it makes me wobble.” He broke into a jolly bubbling laugh so infectious that his hearers smiled with him, and the Inspector came forward from the shadows to join his constable.

“Bad contact somewhere, sir,” he said. “They ought to have fixed it up for you, whoever put your battery in.”

“Not guilty,” said the fat man. “This is my wife’s cycle really. She spins about everywhere like a bird on the wing, I don’t. I remind myself more of a penguin,” and again he bubbled with laughter.

The Inspector turned a torch upon his wrist-watch and appeared to be satisfied with what he saw, for he offered to try to adjust the lamp. “I suppose you’re not very used to it yet, sir,” he said, pulling off the top.

“I am not,” said the cyclist emphatically, “and to tell you the truth I don’t want to be, either, but I’m afraid I shall have to, Heaven reward Hitler with gumboils. When we laid up the car for the duration, my wife said we’d better buy a lady’s cycle as then we could both ride it—alternately, not both at once,” he chuckled. “All in order, constable?”

“Yes, thank you, sir. Not been in these parts long, have you?”

“Only a few weeks. We had a furnished house in London—ours was smashed up in ’41—and the owner wanted it back. So, as my wife was a bit overdone with war-work and housekeeping, and I can work anywhere, I took that cottage at Coveham, next to the smithy, I expect you know it.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Like a fool I missed the Bridport bus this afternoon and had to ride in, and I’ve a horrid feeling I’ve got off the road. This road will take me to Coveham, won’t it, if I can find a left-hand turn somewhere?”

The Inspector laughed. “You’re well off your road, sir. This one doesn’t go anywhere except down to the sea. You’d best go back to the cross-roads you passed, and turn right. That’ll take you home.”

“What, about two miles back? I turned right there, I ought to have gone straight on.”

“That’s right, sir. Do you mind if I just look in your basket?” There was a cycle-basket on the rear carrier.

The fat man laughed again. “By all means, I have no guilty secrets—at least, not in there.” There was a shopping-list, and the contents of the basket tallied with a few omissions. “No suet obtainable,” explained the cyclist. “No matches, no mouse-traps, no bath-salts. I did get half a bottle of whisky, though, shan’t tell you where, and if you drop it I shall complain to the Home Secretary.”

“I wouldn’t do anything so wicked,” said the Inspector. “Well, I don’t think we need detain you any longer, sir. Your lamp’s all right now, look. You know your way, don’t you?”

The cyclist thanked him gratefully, wished them a cheerful good night, and turned the cycle round. “I’ve never ridden in the dark before,” he added. “Pray for me, won’t you?” He hopped violently upon one foot some dozen times in the road before he managed to mount and ride unsteadily away, avoiding a brick with a yelp of comic alarm and another peal of laughter.

“Merry old cuss, isn’t ’e?” said the constable.

“Seems so,” agreed the Inspector. “Well, it’s getting dark now, nearly five o’clock. Hope this fellow won’t be too long, standing in one spot in January isn’t my idea of a piece of cake. Better not smoke, either. Pity, but it can’t be helped.”

The police retired to the shadow of the hollies again and time passed in silence till at last the constable moved suddenly and said, “Listen!” in a low voice. He was right, there were footsteps coming up the lane from the sea, uneven footsteps, which sometimes hurried and sometimes ceased. The Inspector waited till the newcomer was almost upon them and then he stepped out smartly, switching on his torch and saying, “Stop, please,” in a peremptory voice. The beam showed a young man in a raincoat, as thin and eager as the cyclist had been fat and genial.

“Who are you,” babbled the young man, who was evidently in a state of some agitation, “are you——”

“Police,” said the Inspector.

“Thank God,” said the newcomer, and clutched at them. “Let’s go—let’s get away from here. Take me to British Intelligence, I’ve got something frightfully important to tell them—what’s that noise?”

“What noise?”

“Behind the hedge,” said the young man, with the whites of his eyes showing in the torchlight.

“Only a rat in the ditch, these ditches are full of ’em. You come along with us, you’ll be all right.”

* * * * * *

Thomas Elphinstone Hambledon looked across his desk at the man seated uneasily on the edge of a chair. He was a thin young man with untidy dark hair and an anxious expression, his eyes were fixed on Hambledon and he had the air of one who is overcharged with urgent explanations. He waited, with parted lips, to be allowed to begin, and twisted his handkerchief about with his fingers. “Nerves or conscience?” said Hambledon to himself, and opened the interrogation with crisp authority.

“Your name?”

“Abbott. Harold William Abbott.”

“Home address?”

The man gave a number in a street in Nottingham.

“And before the war you were a schoolmaster, I think?”

“Yes, sir. I was modern languages master at St. Raphael’s School, Wigby, near Leicester.”

“So you speak German?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Were you ever in Germany before the war?”

“Er—no, sir.”

“Why did you hesitate?”

“Because I had an invitation to go to Bergisch Gladbach, near Cologne, in the summer holidays of 1939.”

“And you didn’t go.”

“No, sir. It was so obvious that war was imminent, I didn’t want to go and be caught there and interned. Besides, I was in the Territorials and——”

“Who invited you?”

“A German boy who came here two years running with one of those Youth Movement visits to this country which used to be organized before the war. Parties of boys from Germany used to come here in exchange, as it were, for parties of English boys visiting Germany.”

“I remember,” said Hambledon. “How did you come to meet him?”

“I used to help to entertain the German boys. They were sometimes accommodated in schools—St. Raphael’s had them twice—and sometimes we camped out. It was a great help, my speaking German, and I was used to managing boys.”

“This boy’s name?”

“Anton Petsch. He was the son of a chemist in Bergisch Gladbach. He was rather a nice boy and more friendly than some of them.”

“Did you see him again while you were in Germany?”

“No, sir. No doubt he was in the army. He——”

“Or any of the other boys you had met here?”

“No, sir.”

“Or make any attempt to get into touch with him or his family?”

“No, sir. None.”

“Oh. When the war broke out you were called up, of course.”

“Yes, sir. Actually, I was——”

“Regiment?”

“First Bucks, sir.”

“In due course you went to France, and were subsequently taken prisoner—when and where?”

“At Hazebrouck in May, 1940.”

“And you remained in a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany till——”

“October the 17th, 1943. Three years and five months.”

“Now tell me exactly,” said Hambledon, his voice hardening, “how you came to be landed near Coveham on the coast of Dorset in a rubber boat from a German submarine last Saturday.”

Abbott sat a little further back on his chair, rubbed his hands together, and began.

“It’s pretty awful, sir, being a prisoner. It’s the monotony. Especially to a man like me, always used to a lot of mental stimulus. You take up some hobby or study some subject with books from the Red Cross, but nothing seems worth while, if you know what I mean. It seems as though life has always been like that and always will be like that for ever and ever. Every day the same duties, the same hours, the same food, the same faces, the same rules and restrictions, the same things to look at, never anything different unless they bring in some more prisoners—it’s killing. Especially, as I said just now, to a man like me——”

“Get on with the story,” said Hambledon irritably.

“It was on October the eighth last year that I was called into the prison governor’s office and interviewed by a man I’d never seen before——”

“Name?” snapped Hambledon.

“I don’t know, sir. They didn’t say and I didn’t ask. He started by asking me if I were the same Harold Abbott who was formerly a master at St. Raphael’s and had had to do with the visits to England of the Jugenbund—that means the German Youth Movement——”

“I know a little German myself,” said Hambledon coldly. “Continue.”

“I beg your pardon,” said Abbott. “I could not know that. When I said I was the same, this man became very friendly in manner. He said that that proved that I was not so dominated by an ignorant and foolish prejudice against Germany as most Englishmen were—I am quoting his words. I said that that was because I didn’t know so much about Germany in those days,” said Abbott proudly, and looked at Hambledon for approval.

“Go on.”

“He talked a lot about how Germany was certainly winning the war and about how they had no intention of destroying English life and culture. They only wanted the war over without unnecessary destruction and loss of life, and the sooner England gave up the easier the terms would be. England, he said, would still have a great part to play in the future history of the world under the guidance and direction of a victorious Germany. Whereas, if we persisted, they would be compelled to destroy utterly all our cities and crush this senseless defiance with an iron and irrevocable will-to-victory,” said Abbott with a sneer. “He said I had seen for myself the excellence of their methods of training youth. He talked a lot more in the same strain and all the time I wondered what was coming. Eventually he said that I must, as an intelligent man, see that whoever assisted in the smallest degree in bringing about an early termination to a disastrous conflict would not only deserve well of Germany but would be serving England in the truest and highest sense.”

“You have a singularly good memory,” said Hambledon, without enthusiasm.

“I always had,” said Abbott frankly. “When I was a boy——”

“Get on with the story.”

“Eventually he came to the point. Would I go to England and do some simple and interesting work for German Intelligence. Just the compilation of a few facts such as I, an Englishman, would find it easy to——”

“What did you say?”

“I refused, of course.”

“And then?”

“He would not take my refusal as final,” said Abbott. “He said I was to think it over and he would see me again in two days’ time. In the meantime, I had better not tell my fellow-prisoners the subject of our conversation. He suggested that I should tell them that I had been cross-examined about the city of Nottingham—industries, sources of power and so on——”

“All of which they could have got from a sixpenny guidebook before the war,” commented Hambledon. “Was that the end of the interview?”

“Yes. Except that he hinted that if I didn’t agree, I might find life a lot less pleasant than it had been hitherto. I laughed at that,” said Abbott. “Life in a prison camp pleasant! He said I should not find it a laughing matter, and I was shown out.”

“Were you the only prisoner in that camp to be interviewed at that time?”

“So far as I know, yes, but there might have been others interviewed without my knowing it.”

“But surely an extraordinary interview like this would be the subject of discussion all over the camp, among the prisoners, I mean.”

“If they talked about it,” said Abbott unwillingly.

“Do I gather that you didn’t?”

“No, I—you see, an idea struck me——”

“Did you tell the others that you’d been sitting there for—how long? an hour and a half—discussing the public services of Nottingham?

“Yes, I hadn’t time to think up——”

“Think up a better lie. I see. Did your fellow-prisoners believe you, d’you think?”

Abbott wriggled uneasily. “They—I thought they were not quite so friendly——”

“I see. Now, about this bright idea of yours.”

“I thought that if I agreed it was a chance of getting home to England. That was all I cared about. Needless to say I never intended to do a stroke of work for Germany. I proved that when I gave myself up as soon as I landed.”

“You gave yourself up, certainly,” agreed Hambledon. “What happened next? In the prison camp, I mean.”

“The same man came back two days later as he said he would——”

“Give me a detailed description of him.”

Abbott paused for thought. “He was a biggish man, about five foot ten, I suppose. Grey hair, going bald on the top. Broad shoulders, but thin in the body. Blue eyes, sunburnt face. Something the matter with one of his ears—yes, I remember now. The top of his right ear was missing, a war wound I suppose. He wore gold-rimmed glasses. Long thin nose, artificial teeth, clean-shaven——”

“That’ll do. Now go on with the story.”

“He asked me if I’d made up my mind. I said, yes. He asked which way, and I said I’d been thinking over his arguments and come to the conclusion that he was right. Let’s stop this rotten war, I said, and we can sort things out afterwards. He said I had made a wise decision. He told me to wait there, and left the room. Ten minutes later he came back and told me to follow him, we went out to a car and drove away then and there.”

“Any other prisoners see you go?”

“No, sir. We went out of the Governor’s front door, as it were. We drove off and he talked. He was quite nice most of the time, told me I was going to a sort of school near Berlin for training, that I wasn’t to be afraid because everybody would help me. I would be sent to England before long and met there by some more people who would show me what to do and all that. It would be all quite easy. Only, just at the end of the run, he told me what would happen to me if I let them down.” Abbott’s face turned grey, and he shivered. “It was simply beastly, it made me feel sick. And now I have let them down. You don’t think there’s any chance of their getting at me, do you? Can’t I change my name and go back in a different Regiment, or into the Navy instead——”

“You’re going into an internment camp for the present till I make up my mind about you. You’ll be quite safe there. Go on.”

“Internment camp—why, I——”

“I said, go on.”

“The car stopped at a railway station and I was told to get out. Two men came forward and took me away, he stayed in the car, I didn’t see him again. These two men and I got in a train and went to Berlin, and from there in another train to a place about half an hour’s journey. I couldn’t see its name, it was dark when we got there. Then we drove in a car for another quarter of an hour or so and came to a big country house. It was a nice place, had statues on the terraces. It was called Liesensee.” Abbott laughed self-consciously. “I said it was a good name for a place where people were taught to tell lies.”

“Continue to disclose the undecorated truth,” urged Hambledon.

II

IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

Abbott gave a detailed description of his life in one of Germany’s spy schools. “Being an Englishman, there were a lot of things I knew already that the Germans had to learn, but there was a lot to mug up all the same. Radio transmission, secret writing, how to set about collecting information, what to look for, the sort of things they wanted to know and all that. Just like being at school again. It wasn’t too bad really, there was plenty to occupy your mind, and physical drill in the mornings. No games, though, and you were barked at from morning to night. Very strict timetable, musn’t be a minute late, ever. But after the prisoner-of-war camp it was wonderful.”

“Any other British subjects there?”

“Four others, sir.”

“Their names?”

“Nicholls, Little, Tanner and Brampton.”

“Tell me all you know about them.”

“I don’t know much, really, we weren’t allowed to be together and if they saw us talking they came and separated us. I did gather that we’d all had the same idea, it was just a scheme to get home again. Nicholls was some sort of an engineer and Little was something to do with a newspaper, editor, he said. I never heard what Tanner was. Brampton wouldn’t talk about himself much, but he was a Major so he must have been in the Army before the war. He didn’t try to chum up with us at all.”

“Was Major Brampton the only officer?”

“No. Tanner and Little were Lieutenants. I was a Sergeant and Nicholls a Private.”

“How long were you at this school?”

“Three months, sir, twelve weeks, to be exact. October the seventeenth till January the first. At the end of the course we had exams which we all passed, and started on our travels next day, Sunday January the second—last Sunday week, that was. Seems longer ago than that.”

“All five together?”

“We started all together, but Major Brampton disappeared in Berlin.”

“What d’you mean? That he was taken away by himself?”

“I don’t think so, sir. I think he gave the guards the slip and went off on his own. They didn’t tell you anything, but I heard them talking about it. They were in rather a flap, they said they’d get into trouble but no doubt he’d soon be caught. So, no doubt, he was, sir; what could one man do all alone in Berlin?”

“The rest of you went on, I suppose?”

“Yes, by train. That’s when we got our first chance to talk, though even then the guards didn’t like it much.”

“Where did they take you?”

“To Brussels, first. I mean, that was the first place where we got out of the train. We were there for four days, I suppose they were arranging for us to be taken across. We stayed in quite a decent hotel, we had fresh guards there. I imagine the first lot went back to Berlin. We were given instructions about what to do when we landed. I was just to paddle ashore, deflate the dinghy, bury it in the sand, and wait. Someone would say, ‘How far have you come?’ and I was to answer, ‘Forty-seven miles as the crow flies.’ Then he would say, ‘But it’s sixty-three miles by road,’ and then we should each know we’d met the right man.”

“Were the other three given the same password?”

“Yes, sir, except that there were only two others by then. Tanner was killed the night before they gave us our instructions.”

“Do you know anything about Tanner’s death?”

“Oh yes, I was there at the time. It was like this. We’d been kept pretty close in the hotel, just taken out for potty little walks and to see round one or two museums. I enjoyed the museums, the others didn’t. Then one evening the guards came and said as it was our last night on the soil of the Continent for the present anyway, they’d give us a treat and take us out to dinner at a restaurant. It was quite an exciting idea, at least I found it so, I hadn’t had a meal in a restaurant for over three years. So we went to quite a nice place, not very big, and sat at a table in a corner, all six of us. The guards were quite friendly and the food was good, we were enjoying ourselves when suddenly all the lights went out and somebody fired an automatic at us—at least, it sounded like an automatic. I went down flat and so did Little, the guards shouted and one or two people screamed. Next minute the lights went on again and there was Tanner dead in his chair, shot through the head, and one of the guards was wounded. Nicholls hadn’t moved but they’d missed him; Little and I and the other guards weren’t hurt either though they’d fired seven shots at us and smashed the mirror behind us.”

“It is a little difficult to aim accurately in the dark,” said Hambledon.

“They’d have done better with a tommy-gun,” said Abbott.

“So simple,” said Hambledon sarcastically, “taking a tommy-gun into a restaurant without anyone noticing it. Go on.”

“There was an awful row,” said Abbott. “Germans rushed about arresting people and swearing, and our wounded guard was bleeding like a pig all over everything till a first-aid chap came up and looked after him. We were hustled into a car, driven back to our hotel and locked in our rooms. The guards said the men who shot at us were pigs of Belgians in the pay of the Allies and they—the Germans—would make them regret it. Nicholls said, ‘Suppose you don’t catch them?’ and the guard said it didn’t matter, they could always shoot some hostages. Pretty beastly. I hope the men weren’t caught, though it was hard luck on Tanner, wasn’t it, when all he wanted was to get home? He’d got a wife and children in Liverpool, he told me.”

Abbott described how the three survivors—himself, Nicholls, and Little—were taken to Ostend and put on board a submarine, which took them down Channel to the Dorset coast. The submarine surfaced after dark and he was taken up the conning-tower, pushed into a rubber dinghy and told to paddle straight ahead, he could see the shore dimly about a mile away and the sea was flat calm. Then the submarine started her engines again and moved off, taking Nicholls and Little with her. He understood they were going to be put ashore somewhere else.

“So I paddled as fast as I could, jumped ashore leaving the dinghy floating, and ran for it. I wanted to get away before the man came whom I was supposed to wait for. I got off the beach without seeing anybody and ran like blazes, I was happy. Back to England, home and beauty, as they say, it seemed too good to be true. I ran into a tree in the dark and you may think I’m a fool, but I put my arms around it and kissed it; it was an English tree, you see. I expect I was a bit hysterical, I’ve always been rather highly strung. Then the police stopped me, and was I glad to see them, or was I?” Abbott laughed and rubbed his hands together. “I expect you know the rest, don’t you?”

Hambledon asked a few more questions and then touched a bell on his desk; a police officer entered the room.

“I’ve done with this man for the present,” said Hambledon. “You can take him away. I shall probably want to talk to him again in a few days’ time.”

“Where am I going?” asked Abbott.

“Back to Brixton.”

“Brixton jail? But why? I haven’t done anything.”

“Cheer up,” said Hambledon. “Remember, it’s an English jail.”

Hambledon added a few comments to the notes he had taken during his interview with Abbott, and then sent for Nicholls. This man was a good deal older than the schoolmaster, he gave his age as thirty-five. He was a short stocky man with a faint reminiscence of a Scot’s accent, and he gave an address in London. He answered Hambledon’s questions readily but briefly, without any trace of Abbott’s tendency to explain too much.

His name was Edward Nicholls and he had been trained as an engineer, he gave the name of the company. This firm had done a certain amount of business with a German engineering company which made dynamo components. Nicholls said that as he could see that this business was likely to increase, he thought it worth his while to learn German. He went to a night-school for the purpose.

“So you can speak German,” said Hambledon.

“Not too well. I can read it and write it without difficulty, but I never had much practice in speaking it.”

“Not even when you became a prisoner?”

“No. I could understand what the guards said, but I didn’t want to talk to them.”

Nicholls said he thought there might be a chance of being sent to Germany to represent his firm, that was why he took up German. It was about 1928 when he started to learn, and early in 1930 he told the firm that he knew enough German to get along in it, “particularly engineering technical terms.”

“I see,” said Hambledon. “Did they give you a chance to show what you could do?”

“More or less. I had a test, but the junior partner who talked to me said my accent was bad. Still, they put me in that branch of the office and I did some of the correspondence. Then one of the bosses went to Germany on business and took me with him. I was told to listen to how people talked and try to improve myself.”

“Where did you go?”

“Stuttgart. We had a week there.”

“Did you go anywhere else in Germany?”

“No. We went home at the end of the week.”

“Not very long to practise pronunciation.”

“No.”

“Did you like the Germans?”

“Oh, they were all right. They were hot engineers, I’ll say that. Some of their machinery was wonderful.”

“Did you make any friends?”

“No, not to say friends. Some of the German engineers were quite nice fellows, they took me out one or two evenings. I found it a bit of a strain understanding what they said, or I expect I’d have liked it better. They all seemed to talk so fast.”

Hambledon received a fairly clear picture of the stolid engineer being conducted round beer-halls and listening to variety turns with a faintly puzzled frown whenever anybody made a joke and everyone else laughed.

“Did you keep up with any of these men after you went back?”

“One of them wrote once or twice and I answered, but it dropped.”

“What happened after you got back? In the firm, I mean.”

“Oh, I went on in the office for some time—nearly a year. Then the old chap retired, the one who took me to Germany. That’s when I thought I might get the job.”

“And didn’t you?”

“No. They gave it to a young fellow who hadn’t been with the firm long. The nephew of one of the directors. He’d been to school in Germany.”

“So you were frozen out.”

“You could put it like that, but I wasn’t much surprised. These things happen.”

“Didn’t you resent it rather?”

“No. What’s the good?”

“None at all,” said Hambledon. “I agree. I only thought you might have been annoyed.”

Nicholls shook his head. “Disappointed a bit, that’s all.”

“What happened then?”

“Nothing. I went on with the firm for another couple of years. Till March thirty-four.”

Hambledon sighed. He was beginning to feel like a corkscrew getting tired of extracting numerous small corks one after another.

“What happened in March thirty-four?”

“One of the Germans came over and saw me in the office. I mean, he came to see the firm on business, he just happened to see me there.”

“One of those you’d met in Germany?”

“I had met him of course, or he wouldn’t have recognized me. He wasn’t an engineer, he was one of the bosses.”

“Go on,” said Hambledon wearily.

“He told me they wanted a representative in London and would I like the job. The pay was better than what I was getting, so I said yes. Besides, it was a step up.”

“Oh, quite.”

“And if I was working in London it wouldn’t matter if my German accent wasn’t too good.”

“So you took the job.”

“Yes.”

Hambledon sighed again, and learned by degrees that Nicholls had run the German firm’s London office for four years, from 1934 till 1939, apparently to their mutual satisfaction. It seemed to be a perfectly straightforward affair conducted on strictly business lines.

“Did they ever ask you to obtain any information outside the normal current of your business?”

“They did once, some question about aero-engines. I told them I didn’t know and didn’t propose to ask.”

“And that settled that?”

“Yes. They didn’t ask anything like that again. That was in August ’38, we all knew what was coming by then. I didn’t care if I was sacked, the job wouldn’t last much longer anyway.”

Nicholls’ office closed down on the outbreak of war and he promptly enlisted.

“I should have thought you’d have been more useful in a munition factory,” said Hambledon.

“Maybe,” said Nicholls bluntly, “but I wanted a change.”

He was taken prisoner at Dunkirk and remained in a prisoner-of-war camp till October 1943, when he was taken to the Governor’s office for an interview. Nicholls’ account here followed Abbott’s closely except that it was much shorter. “Big feller, with a clip off his right ear. Gassed a lot. Asked me if I’d go to England to work for German Intelligence.”

“What did you say!”

“I said, yes.”

Hambledon looked at Nicholls. “Did he believe you?”

“I suppose so, since I’m here. He talked a lot more about what they’d do to me if I let them down.”

“What did you say to that?”

“Nothing much. ‘I understand,’ or something like that. I was thinking they’d have to catch me first.”

Hambledon was thinking that the German Intelligence must be extremely short of agents if they tried to enlist this lump of granite. Though that was, of course, always a Nazi mistake; the psychological error of thinking that any man could be bent to their will if they only pushed him hard enough. Nicholls described the German spy school in a few brief sentences, he did not seem to have been particularly impressed. He said it was “too much like the story-books. Secret inks, and all that.”

Asked about his fellow-prisoners, Abbott, Little, Tanner and Brampton, he said that they had not been allowed to talk together and he had not bothered to try. “It wasn’t as though we were trying to escape together. All we had to do was to sit tight and do as we were bid.” Abbott, he said, was a “gasbag. Always bursting with lots to say and nothing in it when it was said. A bit hysterical.” Tanner was “a very quiet gentleman, an officer. I was a bit surprised he’d gone in for it. I suppose he wanted to get home, like the rest of us.” Little was also an officer, something to do with newspapers before the war. Nicholls had not much to say about Little, “he talked about things I wasn’t interested in. He and Abbott were pretty friendly. Lieutenant Tanner and I kept out of it.”

“And the fifth man?” said Hambledon. “Major Brampton?”

Nicholls shook his head. “Hardly knew him. He only travelled as far as Berlin with us.”

“What happened to him, do you know?”

“No idea, he just disappeared. Abbott said he’d escaped, but I doubt it. He couldn’t speak any German.”

“Are you sure of that?”

“Quite. He was always getting cursed at the spy school for not understanding what they said to him. So was Little, but Abbott used to prompt him. Major Brampton was different.”

“How, different?”

“Oh, one of the huntin’, shootin’ and fishin’ crowd. You know, you can always tell. Good officer, I daresay, but a silly ass over things he thought weren’t important. He behaved as though the spy school was a silly game, but he came out top of the exams all the same.”

“Oh, did he?”

Nicholls actually laughed. “He used to rile the Germans no end. ‘My good man,’ he used to say.” Nicholls mimicked a rather haw-haw voice. “ ‘My good man, don’t do that.’ Always looked as though he wasn’t listening, and then came out on top.”

“I thought you said you hardly knew him,” said Hambledon, with a laugh.

“Never spoke to me at all, only ‘good morning, Nicholls.’ And I’d say, ‘good morning, sir.’ He used to speak to Mr. Tanner sometimes, don’t know what about.”

When Nicholls was pushed off from the submarine in his rubber boat, he made no attempt to row ashore at once, but lay off until it was daylight. He then waited till he saw some soldiers on the beach, rowed in and gave himself up. “I thought if there was a reception committee waiting for me, they could just wait.”

“Quite,” said Hambledon. “Very sensible.” Nicholls was ultimately dismissed under escort, he made no fuss about returning to Brixton Jail.

Little was then brought in. Hambledon put him through the same sieve as the other two, but gained very little more information than he had already gleaned from Abbott and Nicholls. Little was rather of the Abbott type, but more intelligent and practical. He admitted frankly that he had been favourably impressed by the early achievements of the Nazi party, but pointed out that he was not the only one; quite a lot of English people thought as he did.

Little was editor of a small provincial newspaper, and after attending a couple of meetings arranged by German sympathizers and addressed by plausible and fluent Germans, he wrote a series of articles on The Re-birth of Germany and published them in his paper. This was in 1935. Not long after this he was approached by an organization for the encouragement of Anglo-German friendly relations, thanked for what he had written, and invited to pay a visit to Germany to see the wonders of the Re-birth for himself. He went.

“Enjoy yourself?” asked Hambledon.

Little had enjoyed himself, in a way. He was handicapped by knowing no German; “I still don’t,” he added. “I’m a complete dud at languages, always was.” He was taken about, beamed upon, and shown what it was thought advisable for him to see. It was very well done.

“What did you mean when you said just now that you enjoyed yourself ‘in a way’?”

“When I came to see for myself, it was all a bit too military for my taste. I was rather a pacifist in those days,” said Little, with disarming frankness. “I changed my mind later. But I thought then there was a lot too much drill and not enough Swedish exercises, if you see what I mean. Physical training, yes, but even then you could see what was aimed at.”

“Did you ever visit Germany again?”

“No,” said Little. “For a long time I used to be bombarded with literature from Nazi sources, big envelopes full of leaflets on all sorts of subjects gradually working round to the iniquities of the Versailles Treaty and how badly Germany had been treated and all that stuff. I expect you saw it, there was a lot of it about at one time.”

“What did you do about it?”

“Joined the Territorials,” said Little cheerfully.

After Little had been removed, Hambledon talked the matter over with Chief-Inspector Bagshott of Scotland Yard, who was at the time on special duty with the Security Police. He was an old friend of Hambledon’s and accustomed to his methods, which he sometimes deprecated and sometimes envied.

“I think their stories are probably true,” said Tommy.

“I thought the Germans were an intelligent race,” said Bagshott.

“Only in spots,” said Hambledon. “Large red spots with purple frills round them.”

“Surely,” pursued Bagshott, “they could not really have believed that any of these men would be of the slightest use to them. It must have been obvious that these prisoners only agreed in order to get home.”

“You don’t appreciate the Nazi mentality,” said Tommy. “Imagine the case the other way round. Suppose we’d freed German prisoners with the same tale and they had gone home and reported to the police, which would mean the Gestapo. Do you suppose they would have been believed? Not on your life. ‘But why,’ the Gestapo would say, ‘did the accursed English pick on you? There must have been something about you which led them to suppose you would fall in with this scheme. No true Nazi would countenance it for a moment. He would spit in the face of the tempter. You are politically suspect.’ When the German protested that he had reported himself at once to the police, they would reply ‘Of course. What else could you do? It is the first obvious step towards establishing confidence, under cover of which to serve the enemies of the Reich. You are from-the-bottom-of-your-liver unreliable. You are probably Jewish.’ It’s wonderful,” added Hambledon in passing, “what a lot of Germans do have a Jewish skeleton in their family vaults. The end of the interview would open the door of a concentration camp, or more likely—“Hambledon levelled an imaginary rifle—“bang, bang! Bury me this carrion. Is that a quotation from Shakespeare?”

“I don’t know,” said Bagshott. “But——”

“I can’t account for it,” said Hambledon, “but I often say things that sound to me like Shakespeare. You know——”

“What you mean,” interrupted the Chief-Inspector, “is that these Nazis are so untrustworthy themselves that they can’t trust anybody else.”

“Precisely. Untrust begets untrust, and liars, lies. There I go again, it even scans.”

“So the Germans think the English wouldn’t dare to come to us for fear of being put into a concentration camp,” pursued Bagshott.

“That’s it.”

“But that’s exactly what we shall do with ’em, isn’t it? Detained under 18B?”

“Till we’re satisfied with their bona-fides, yes,” said Hambledon. “But our concentration camps and the Germans’ have nothing in common but the name. I ought to know, I used to——”

The door opened and a man came in saying, “Excuse me, sir,” to Hambledon. “Brixton prison on the telephone. Did you direct the first prisoner, Abbott, to be taken anywhere else instead of back there? Or possibly on the way there?”

“What? No, I certainly didn’t. I sent him straight back in charge of the man who brought him. Why?”

“Because they should have arrived two hours ago and they haven’t done so.”

Hambledon glanced at Bagshott who rose to his feet and reached for the telephone. “May I—thanks. Put Brixton through to me here, please.”

The man left the room and Hambledon said, “That’s odd. There may have been an accident.”

“Brixton ought to have been informed,” began Bagshott, but the telephone started to squeak and he broke off to listen. He asked a few questions and ended by saying, “I will see into it at once. Good-bye.” He put the receiver down and went on, “The escort was a Special Branch man named Warren. He was instructed to bring the prisoner in an ordinary taxi and take him back in the same way. The three prisoners were brought separately, of course, with separate escorts at different times, but all by taxi. I am going to look for Abbott and Warren now, I’ll ring you up as soon as I hear anything.”

“If it’s really interesting, come and tell me,” said Hambledon. “Or bring the men here if they have anything exciting to say. In an hour’s time will do, I’m going to have dinner now.”