5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

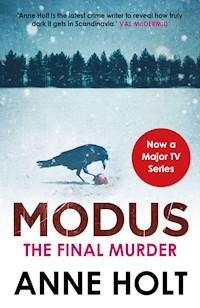

A TV talk-show star is found killed in her home, her tongue removed and left near to the body. When a second body, that of a prominent politician, is found crucified soon after, Superintendent Adam Stubo is called in to lead the investigation of both murders. Unable to establish whether these two gruesome slayings are linked, or what the meaning is behind the manner of death, Stubo calls in his psychologist wife Johanne Vik to help. As Vik reviews the crimes she begins to see a pattern that chills her to the core. If her theory is correct then more killings will follow, and the spree will end in the murder of the investigating officer: Adam Stubo. From internationally bestselling author Anne Holt, The Final Murder is a dark and gripping novel.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

THE FINAL MURDER

ANNE HOLT spent two years working for the Oslo Police Department before founding her own law firm and serving as Norway’s Minister for Justice during 1996–1997. Her first book was published in 1993 and she has subsequently developed two series: the Hanne Wilhelmsen series and the Johanne Vik series. Both are published by Corvus.

ALSO BY ANNE HOLT

THE JOHANNE VIK SERIES: PUNISHMENT THE FINAL MURDER FEAR NOT

THE HANNE WILHELMSEN SERIES: THE BLIND GODDESS BLESSED ARE THOSE THAT THIRST DEATH OF THE DEMON THE LION’S MOUTH DEAD JOKER WITHOUT ECHO THE TRUTH BEYOND 1222

THE FINAL MURDER

Anne Holt

Translated by Kari Dickson

First published in the English language in Great Britain in 2009 by Sphere, an imprint of Little, Brown Book Group.

This edition published in 2011 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Originally published in Norwegian as Det som aldri skjer in 2004 by Piratforlaget AS, Postbooks 2318 Solli, 0201 Oslo.

Published by agreement with the Salomonsson Agency.

Copyright © 2006, Anne Holt. Translation copyright © 2007, Kari Dickson.

The moral right of Anne Holt to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-85789-439-7 Paperback ISBN: 978-1-84887-614-9

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26-27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

THE FINAL MURDER

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part 1

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

Thursday 4 June 2004

Postscript

For people today, only one radical shock remains – and it is always the same: death.

Walter Benjamin, Central Park

She no longer knew how many people she had killed. It didn’t really matter anyway. Quality was more important than quantity in most professions. And that was true of her business too, although the pleasure she once gained from an innovative twist had dwindled over the years. More than once, she’d considered what else she might do. Life was full of opportunities for people like her, she thought to herself every now and then. Rubbish. She was too old, she felt tired. This was the only thing she could really do. And it was a lucrative business. Her hourly rate was sky-high now, naturally, but so it should be. It took a while to recover afterwards.

The only thing she really enjoyed was doing nothing. And where she was now, there was nothing to do. But she still wasn’t happy.

Perhaps it was a good thing that the others hadn’t come, after all.

She wasn’t sure.

The wine was certainly overrated. It was expensive and left a sour taste in her mouth.

I

To the east of Oslo, where the hills flatten out down towards Lørenskog, a station town by the Nita River, cars had frozen solid overnight. People on foot pulled their hats down over their ears and wrapped their scarves tighter round their necks as they trudged the few perishing kilometres to the bus stop on the main road. The houses in the small cul-de-sac fended off the frost with drawn curtains and snowdrifts that blocked the driveways. Huge icicles hung from the eaves of an old wooden villa at the end of the road down by the woods, disasters in waiting. The house was white.

Inside the front door with its lead glass and moulded brass handle, at the end of the unusually spacious hall, to the left in a study, dominated by minimalist art and lavish furniture, sitting behind an imposing desk between boxes of unopened letters, was a dead woman. Her head had fallen back and her hands rested on the arms of her chair. A track of dried blood ran from her lower lip, down her bared neck, split round her breasts and then joined again on her impressively flat stomach. Her nose was also bloody. In the light from the ceiling lamp, it looked like an arrow pointing to the dark hole that had once been a mouth. Only a stump remained of her tongue, which had obviously been carefully removed. The cut was clean and sharp.

It was warm in the room, almost too hot.

Detective Inspector Sigmund Berli from the Norwegian National Criminal Investigation Service, the NCIS, finally closed his mobile phone and looked over at a digital thermometer just inside the southeast-facing panorama window. Outside, it was nearly 22 degrees below freezing.

‘Amazing that the windows don’t break,’ he said, carefully tapping the windowpanes. ‘Forty-seven degrees difference between inside and outside. Incredible.’

No one seemed to pay him any attention.

Under her silk dressing gown with its golden collar, the dead woman was naked. The belt lay on the floor. A youngish policeman from the Romerike Police took a step back when he saw the yellow coil.

‘Shit,’ he gasped, then ran his fingers through his hair in embarrassment. ‘I thought it was a snake, like.’

The woman’s missing body part lay beautifully wrapped in paper on the blotter on the desk in front of her, only the tip protruding from the middle of all the red. A plump, exotic plant; pale flesh with even paler taste buds and purple red wine stains in the folds and cracks. A half-empty glass was balanced on a pile of papers near the edge of the desk. The bottle was nowhere to be seen.

The detective sergeant cleared his throat. ‘Can’t we at least cover her tits? It just seems mean that she has to . . .’

‘We’ll have to wait,’ Sigmund Berli replied as he put his mobile back into his breast pocket. ‘I’m going to keep trying.’

He went down on one knee to get a closer look at the dead woman.

‘Adam would be interested in this,’ he muttered. ‘So would his wife, for that matter.’

‘What?’

‘Nothing. Do we know anything about the timing yet?’

Berli stifled a sneeze. The silence in the room made his ears ring. He got up and needlessly brushed dust from his trousers with stiff movements. A uniformed policeman was standing by the door to the hall. He had his hands behind his back and was shifting his weight from one foot to the other as he stared out of the window, away from the body. Some Christmas lights still hung in one of the spruce trees. Here and there, you could see the bulbs glowing dimly under the branches and tightly packed snow, where it was dark.

‘Does nobody know anything here?’ Berli barked in irritation. ‘Don’t you even have a provisional time of death?’

‘Yesterday evening,’ the other man eventually replied. ‘But it’s too early . . .’

‘To say,’ Sigmund Berli finished his sentence. ‘Yesterday evening. Pretty vague, in other words. Where’s . . .?’

‘They’re away every Tuesday. The family, that is. Husband and daughter, who’s six. If that’s what you . . .’

The sergeant smiled uncertainly.

‘Yes,’ Berli said and walked halfway round the desk.

‘The tongue,’ he started and peered at the package on the desk. ‘Was it cut off while she was still alive?’

‘Don’t know,’ the sergeant answered. ‘I’ve got all the papers for you here. As we’ve finished examining everything and everyone’s back at the station, you might . . .’

‘Yes,’ Berli said, but the sergeant wasn’t sure what he was agreeing with. ‘Who discovered the body, if the family was away?’

‘The cleaner. A Filipino who comes every Wednesday morning at six. He starts down here, he said, so he doesn’t wake anyone too early, and then works his way up. The bedrooms are upstairs, on the first floor.’

‘Yes,’ Berli repeated with no interest. ‘Away every Tuesday?’

‘That’s what she said,’ the sergeant answered. ‘In all the interviews and suchlike. She sends her husband and daughter away every Tuesday. Then she goes through all her letters herself. It’s a matter of principle . . .’

‘Right,’ mumbled Berli cynically, and stuck a pen into one of the boxes of letters. ‘I can believe that. It’d be impossible for one person to go through all of this.’

He pointed at the dead woman again.

‘Sic transit gloria mundi,’ he said and peered into her mouth. ‘Her celebrity status isn’t much good to her now.’

‘We’ve already gathered lots of clips and cuttings and everything is ready . . .’

‘Yeah, yeah.’

Berli waved him away. The silence was overwhelming. No people could be heard on the street, no clocks ticked, the computer was turned off. The red cyclops eye of a radio stared at him mutely from the glass cabinet by the door. There was a Canada goose on the mantelpiece, frozen in flight. Its feet were faded and it had hardly any feathers left in its tail. The ice-cold daylight painted a colourless rectangle on the carpet under the south-facing window. Sigmund Berli could hear his blood pounding in his ears. The uncomfortable feeling of being in a mausoleum made him run his finger down his nose. He couldn’t decide whether he was irritated or at a loss. The woman still sat in the chair with her legs open, bare breasts and a tongueless gaping hole. It was as if the horrendous crime had robbed her not only of an important body part, but also of her humanity.

‘You lot always get pissed off if you’re called in too late,’ the sergeant said eventually, ‘so we just left everything as it was, even though we’re done with most things . . .’

‘We will never be done,’ Berli said. ‘But thank you. Smart thinking. Especially with this lady. Does the press . . .?’

‘Not yet. We hauled in the Filipino and we’ll hold him for questioning for as long as we can. We’ve been as careful as possible outside. Securing the evidence is important though, especially in snow like this and suchlike, so I’m sure the neighbours are wondering what’s going on. But no one can have tipped off the press yet. And in any case, they’re all too busy with the new princess right now.’

A fleeting smile became serious.

‘But then again, obviously . . . Fiona from On the Move withFiona murdered. In her own home and in this way, well . . .’

‘In this way,’ Berli nodded. ‘Strangled?’

‘The doctor thinks so. No stab wounds, no bullets. Marks on her throat, you can see . . .’

‘Mmmm. But take a look at this!’

Berli studied the tongue on the desk. The paper was elaborately folded, like a low vase with an opening for the tip of the tongue and elegant, symmetrical wings.

‘Almost looks like a petal,’ the younger policeman said and wrinkled his nose. ‘With something horrible in the middle. Quite . . .’

‘Striking,’ Berli muttered. ‘Whoever did it must have made this beforehand. I can’t imagine you’d kill someone like this and then take time out to do a bit of origami.’

‘I don’t think there’s any suspicion of sexual abuse.’

‘Origami,’ Sigmund Berli repeated. ‘The Japanese art of paper folding. But . . .’

‘What?’

Berli bent down even closer to the severed organ. The sergeant did the same. The two policemen stood like this for a while, forehead to forehead, breathing in time with each other.

‘It’s not just been cut off,’ Berli said finally and straightened his back. ‘The tongue has been split. Someone has split the end in two.’

For the first time since Sigmund Berli arrived at the scene of the crime, the uniformed policeman at the door turned towards them. He looked like a teenager, with an open face and spots. He ran his tongue over his lips, again and again, while his Adam’s apple jumped up and down above his tight collar.

‘Can I go now?’ he whimpered. ‘Can I go?’

*

‘Throneowning,’ the young girl said and smiled.

The half-dressed man drew the razor slowly down his throat before rinsing it and turning round. The child was sitting on the floor, pulling her hair through the holes in an old swimming cap.

‘You can’t go like that, love,’ he said. ‘Come on, let’s take it off. We can find the hat you got for Christmas, instead. You want to look beautiful when you meet your sister for the first time, don’t you?’

‘Throneowning,’ Kristiane repeated and pulled the swimming cap on even further. ‘Hairgrowing. Throne hair.’

‘Do you mean heir to the throne?’ asked Adam Stubo, rinsing off what was left of the shaving foam on his face. ‘That’s someone who’s going to be a king or queen in the future.’

‘My sister’s going to be a queen,’ Kristiane replied. ‘You’re the biggest man in the world, really.’

‘You think so?’

He lifted the girl up and held her on his hip. Her eyes roamed uncertainly, as if eye contact and touch at the same time would be too much. She was nearly ten and small for her age.

‘Heir to the throne,’ Kristiane said to the ceiling.

‘That’s right. We’re not the only ones who had a little girl today. So did . . .’

‘Princess Mette-Marit is so pretty,’ the child interrupted and clapped her hands. ‘She is on TV. We had cheese on toast for breakfast. Leonard’s mummy said a princess had been born. My sister!’

‘Yes,’ Adam said, and put her down again before carefully trying to remove the swimming cap without pulling her hair too much. ‘Our baby is a beautiful princess. But she’s not heir to the throne. What do you think she should be called?’

The cap came off eventually. Her long hair clung to the inside, but Kristiane didn’t seem to feel any pain as he loosened the rubber from her head.

‘Abendgebet,’ she said.

‘That means evening prayers,’ he explained. ‘That’s not her name. The girl in the picture above your bed, I mean. It’s German for what the girl is doing . . .’

‘Abendgebet,’ Kristiane said.

‘Let’s see what Mummy says,’ Adam said, and pulled on his trousers and shirt. ‘Go and find the rest of your clothes. We have to get a move on.’

‘Move on,’ Kristiane repeated, and went out into the hall. ‘Hoof on. Cows and horses and small pussy cats. Jack! King of America! Do you want to visit the baby too?’

A big mongrel with yellowy-brown fur and a tongue hanging out of his smiling mouth came tearing out of the girl’s bedroom. He whined eagerly and scampered in circles round the girl.

‘Jack will have to stay at home,’ Adam told her. ‘Now, where’s your hat?’

‘Jack’s coming with us,’ Kristiane said cheerfully and tied a red scarf round the dog’s neck. ‘The heir to the throne is his sister too. Leonard’s mummy says we’ve got equality in Norway, so girls can do what they want. And you’re not my daddy. Isak’s my daddy. So there.’

‘All very true,’ Adam laughed. ‘But I love you lots. And now we have to go. Jack has to stay at home. Dogs aren’t allowed in hospitals.’

‘Hospitals are for sick people,’ Kristiane said as he put on her coat. ‘The baby’s not sick. Mummy’s not sick. But they’re still in hospital. Spot the pill.’

‘You’re a little rationalist, you are.’

He kissed her and pulled her hat down over her ears. Suddenly she looked him straight in the eye. He stiffened, as he always did in these rare moments of openness, unexpected glimpses into a mind that no one could fully grasp.

‘An heir to the throne has been born,’ she quoted ceremoniously from the morning’s announcements on TV, before taking a breath and continuing: ‘A great event for the nation, but most of all, for the parents. And we are delighted that it is a bonny princess this time.’

A muffled ringing interrupted from the coat rack.

‘Mobile telephone,’ she said mechanically. ‘Dam-di-rum-ram.’

Adam Stubo stood up and frantically felt all the pockets in the chaos of jackets and coats until he finally found what he was looking for.

‘Hallo,’ he said reluctantly. ‘Stubo here.’

Kristiane calmly started to take off her outdoor clothes again. First the hat, then the coat.

‘Hold on a moment,’ Adam said into the phone. ‘Kristiane! Don’t . . . Wait a moment.’

The girl had already taken off most of her clothes and was standing in her pink pants and vest. She pulled her tights down over her head.

‘No way,’ Adam Stubo said. ‘I’ve got fourteen days’ paternity leave. I’ve been awake for over twenty-four hours, Sigmund. Jesus, my daughter was born less than five hours ago and now . . .’

Kristiane arranged the legs of her tights like two long plaits down her front.

‘Pippi Longstocking,’ she said, pleased with herself. ‘Diddle, diddle, tra la la la la.’

‘No,’ Adam said so brusquely that Kristiane got a fright and started to cry. ‘I’ve got time off. We’ve just had a child. I . . .’

Her crying morphed into a long howl. Adam never got used to this slight child’s howling.

‘Kristiane,’ he said in desperation. ‘I’m not angry with you. I was talking to . . . Hallo? I can’t. No matter how spectacular the whole thing is, I can’t leave my family right now. Goodbye. And good luck.’

He snapped the phone shut and sat down on the floor. They should have been at the hospital a long time ago.

‘Kristiane,’ he said again. ‘My little Pippi. Can you show me Mr Nelson?’

He knew better than to hug her. Instead, he started whistling. Jack lay down on his lap and fell asleep. A damp patch grew on his trousers under the dog’s open, snoring mouth. Adam whistled and hummed and sang all the children’s songs he could think of. The girl stopped crying after forty minutes. Without looking at him, Kristiane pulled the tights off her head and slowly started to get dressed.

‘Time to visit the heir to the throne,’ she said flatly.

The mobile phone had rung seven times.

He hesitated before turning it off, without listening to the messages.

*

A week had passed and the police were obviously no further forwards. It didn’t surprise her.

‘Internet reports are useless,’ the woman with the laptop said to herself.

As she hadn’t bothered to subscribe to a local server, it was also extortionate to surf the net. She got stressed when she thought of all that money being eaten up while she waited for a connection on the slow, analogue line to Norway. She could, of course, go to Chez Net. They charged five euros for fifteen minutes and had broadband. But unfortunately the place was full of drunk Australians and braying Brits, even now in winter. So she didn’t bother, not now anyway.

There was remarkably little fuss in the first days after the murder. The little princess had the full attention of the media circus. The world truly wanted to be deceived.

But then it started to get more coverage.

The woman with the laptop simply could not stand Fiona Helle. It was an unbearably politically correct response, but there wasn’t much to be done about that. She read phrases like ‘loved by the people’ in the papers. Which was fair enough, given that the programme had been watched by well over a million viewers every Saturday, for five series in a row. She had only seen a couple of shows, just before she came away. But that was more than enough to realize that for once she agreed with the cultural snobs’ usual, unbearably arrogant, condemnation of popular entertainment. In fact, it was just one such vitriolic criticism in Aftenposten, written by a professor of sociology, that made her sit down in front of the television one Saturday evening and waste one and a half hours watching On the Move with Fiona.

But it hadn’t been a total waste of time. It was ages since she had felt so provoked. The participants were either idiots or deeply unhappy. But they could hardly be blamed for being either. Fiona Helle, on the other hand, was successful, calculating, and far from true to her love of the common people. She waltzed into the studio dressed in creations that had been bought worlds away from H&M. She smiled shamelessly at the camera, while the poor creatures revealed their pathetic dreams, false hopes and, not least, extremely limited intelligence. Prime time.

The woman, who now got up from the desk by the window and walked around the unfamiliar sitting room without knowing quite what she wanted, did not normally join in public debate. But after watching one episode of On the Move with Fiona she had been tempted. Halfway through writing a letter from an ‘outraged reader’, she’d stopped and laughed at herself before deleting it. She had been in a good mood for the rest of the evening. As she couldn’t sleep, she allowed herself to indulge in a couple of TV3’s terrible late-night films and had even learnt something from them, if she remembered rightly.

At least feeling angry was a form of emotion.

Readers’ letters in newspapers were not her chosen form of expression.

Tomorrow she would go into Nice and see if she could find some Norwegian papers.

II

It was night in the duplex villa in Tåsen. Three sad street lights stood on the small stretch of road behind the picket fence at the bottom of the garden, the bulbs long since broken by excited children with snowballs in their mitts. It seemed that the neighbourhood was taking the request to save electricity seriously. The sky was clear and dark. To the northeast, over Grefsenåsen, Johanne could make out a constellation she thought she recognized. It made her feel that she was totally alone in the world.

‘You standing here again?’ asked Adam with resignation.

He stood in the doorway, sleepily scratching his groin. His boxer shorts were stretched tight over his thighs. His naked shoulders were so broad that he almost touched both sides of the doorway.

‘How much longer is this going to carry on, love?’

‘Don’t know. Go back to bed.’

Johanne turned back to the window. The transition from living in a block of flats to a house in this neighbourhood had been harder than she’d expected. She was used to complaining water pipes, babies’ cries that travelled through the walls, quarrelling teenagers and the drone of late-night programmes from downstairs, where the woman on the ground floor who was nearly stone-deaf often fell asleep in front of the telly. In a flat you could make coffee at midnight. Listen to the radio. Have a conversation, for that matter. Here, she barely dared open the fridge. The smell of Adam’s nocturnal leaks lingered in the bathroom in the morning, as she had forbidden him to disturb the neighbours below by flushing before seven.

‘Why do you creep around so?’ he said. ‘Can’t you at least sit down?’

‘Don’t talk so loud,’ Johanne whispered.

‘Give me a break. It’s not that loud. And you’re used to having neighbours, Johanne!’

‘Yes, lots. But they’re more anonymous. You’re so close here. It’s just them and us, so it’s more . . . I don’t know.’

‘But we get on so well with Gitta and Samuel! Not to mention little Leonard! If it wasn’t for him, Kristiane would hardly have any . . .’

‘I mean, look at these!’

Johanne stuck out a foot and laughed quietly.

‘I’ve never had slippers before in my life. Hardly dare to get out of bed without putting them on now!’

‘They’re sweet. Remind me of little toadstools.’

‘They’re supposed to look like toadstools, that’s why! Couldn’t you have got her to choose something else? Rabbits, bears? Or even better, completely normal brown slippers?’

The parquet creaked with every step he took towards her. She pulled a face before turning back to the window again.

‘It’s not exactly easy to get Kristiane to change her mind,’ he said. ‘Please stop being so anxious. Nothing is going to happen.’

‘That’s what Isak said when Kristiane was a baby too.’

‘That was different. Kristiane . . .’

‘No one knows what’s wrong with her. So no one can know if there’s anything wrong with Ragnhild.’

‘Oh, so we’re agreed on Ragnhild, then?’

‘Yes,’ Johanne said.

Adam put his arms round her.

‘Ragnhild is a perfectly healthy eight-day-old baby,’ he whispered. ‘She wakes up three times a night for milk and then goes straight back to sleep. Just like she should. Do you want some coffee?’

‘OK, but be quiet.’

He was about to say something. He opened his mouth, but then imperceptibly shook his head instead, picked up a sweater from the floor and pulled it on as he went out to the kitchen.

‘Come and sit down in here,’ he called. ‘If you absolutely must stay awake all night, let’s at least do something useful.’

Johanne pulled up a bar stool to the island in the middle of the kitchen and tightened her dressing gown. She absent-mindedly picked through a thick file that shouldn’t be lying in the kitchen.

‘Sigmund doesn’t give up, does he?’ she said and rubbed her eyes behind her glasses.

‘No, but he’s right. It’s a fascinating case.’

He turned round so quickly that the water in the coffee jug spilt.

‘I was only at work for an hour,’ he said defensively. ‘From the time I left here until I got back was only . . .’

‘OK, OK, don’t worry. That’s fine. I understand that you have to go in every now and then. I have to admit . . .’

On the top of the pile was a photograph, a flattering portrait of a soon-to-be murder victim. The shoulder-length hair with a middle parting made her narrow face look even thinner. Not much else about Fiona Helle was old-fashioned. Her eyes were defiant, her full lips smiled confidently at the lens. She was wearing heavy eye make-up, but somehow managed to avoid looking vulgar. In fact, there was actually something quite captivating about the picture, an obvious glamour that contrasted sharply with the down-to-earth, family-friendly programme profile she had so successfully built up.

‘What do you have to admit?’ asked Adam.

‘That . . .’

‘That you think this case is bloody interesting too,’ smirked Adam, banging around with the cups. ‘I’m just going to get a pair of trousers.’

Fiona Helle’s background was no less fascinating than the portrait. She graduated in History of Art, Johanne noted as she read. Married Bernt Helle, a plumber, when she was only twenty-two; they took over her grandparents’ house in Lørenskog and lived there without children for thirteen years. The arrival of little Fiorella in 1998 had obviously not put any brakes on either her ambition or her career. Quite the opposite in fact. Having gained cult status as a presenter for the arty Cool Culture on NRK2, she was then snapped up by the entertainment department. After a couple of seasons on a late-night chat show on Thursdays, she finally made it. At least, that was the expression she used herself, in the numerous interviews she had given over the past three years. On the Move with Fiona was one of national TV’s greatest successes since the sixties, when there was little else for people to do other than gather round their TV screens to watch the one channel and share the experience of what a Saturday night was in Norway.

‘You liked those programmes! A grown man sitting there crying!’

Johanne smiled at Adam, who had come back wearing a bright-red fleece, grey tracksuit bottoms and orange woollen socks.

‘I did not cry,’ Adam protested, pouring the coffee into the cups. ‘I was touched, though, I admit that. But cry? Never!’

He moved a stool in closer to her.

‘It was that episode about the war baby whose father was a German soldier,’ he remembered quietly. ‘You’d have to have a heart of stone not to be moved by her story. Having been persecuted and bullied throughout her childhood, she goes to the US and gets a job cleaning floors in the World Trade Center when it was first built. Then she took her first and only day off sick on the eleventh of September. And she had always remembered the little Norwegian boy next door who . . .’

‘Yeah, yeah,’ said Johanne, wetting her lips with the steaming hot coffee. ‘Shhh!’

She froze.

‘It’s Ragnhild,’ she said tersely.

‘It’s not,’ he started, trying to catch her before she ran into the bedroom.

Too late. She rushed across the floor without a sound and disappeared. Only her anxiety remained. A bitterness gripped his stomach and made him pour more milk in his coffee.

His story was worse than hers. But to compare was not only mean, it was impossible. Pain cannot be measured and loss cannot be weighed. All the same, he couldn’t help it. When they first met one dramatic spring, nearly four years ago now, he had found himself getting irritated a little too often by Johanne’s sorrow at Kristiane’s strangeness.

She had a child, after all. A child that was alive and had a voracious appetite for life. Different from most, but in her own way Kristiane was a lovely and very alert young child.

‘I know,’ Johanne said suddenly. She had come round the corner from the hall without him noticing. ‘You’ve had to deal with more than me. Your child is dead. I should be grateful. And I am.’

A quiver in his lower lip, barely visible in the dim light, made her stop. His hand covered his eyes.

‘Was Ragnhild OK?’ Adam asked.

She nodded.

‘I just get so frightened,’ she whispered. ‘When she’s asleep, I’m scared that she’ll die. When she’s awake, I think she’s going to die. Or that something will happen.’

‘Johanne,’ he said, helplessly, and patted the chair beside him. ‘Come here and sit down.’

She sank down beside him. His hand rubbed her back, up and down, just a bit too roughly.

‘Everything’s fine,’ he said.

‘You’re angry,’ she whispered.

‘No.’

‘You are.’

His hand stopped, and he squeezed her gently on the neck.

‘No, I said. But now . . .’

‘Can’t I just be . . .’

‘D’you know what?’ he interrupted with forced jolliness. ‘Let’s just agree that the children are fine. Neither of us can sleep. So now we can take an hour or so to look at this . . .’ He tapped Fiona Helle’s face with his stubby fingers. ‘And then we can see whether it’s possible to sleep. OK?’

‘You’re so good,’ she said and wiped her nose with the back of her hand. ‘And this case is worse than you fear.’

‘Right.’

He finished his coffee and pushed the cup out of the way before spreading the papers over the large counter. The photograph lay between them. He ran his finger over Fiona Helle’s nose, circled her mouth and paused a moment before picking up the picture and looking at it closely.

‘What exactly do you think we’re worried about?’

‘No clues whatsoever,’ she said lightly. ‘I skimmed through all the papers.’

She was looking for a document without finding it.

‘To begin with,’ she sniffed, ‘the footprints in the snow are as good as useless. OK, there were three prints on the driveway that probably belong to the killer, but the combination of the temperature, wind and snow makes their value limited. The only thing that is certain is that whoever did it had socks on over their shoes.’

‘Ever since the Orderud case, every bloody petty thief has used that trick,’ he grumbled.

‘Watch your language.’

‘They’re asleep.’

‘The shoe size is between forty-one and forty-five, in other words the same as around ninety per cent of the male population.’

‘And a small share of the female population,’ he smiled. Johanne tucked her feet in under the bar stool.

‘In any case, using shoes that are too big for you is another well-known trick. And it’s not possible to gauge the killer’s weight from the footprints. He was simply very lucky with the weather.’

‘Or she.’

‘Could be a she. But to be honest, you’d need to use quite a lot of force to overpower Fiona Helle. A fit lady in her prime.’

They looked at the picture again. The woman looked good for her age. Her forty-two years were apparent around the eyes, there were visible wrinkles around her mouth, and her lipstick had bled. But there was still something vibrant about her face, the direct look in her eyes, the firm skin on her neck and cheeks.

‘Her tongue was cut out while she was still alive,’ Adam said. ‘The theory so far is that she lost consciousness through strangulation and then her tongue was cut out. The bleeding was so heavy that she can’t have been dead. Maybe the killer chose his method with care, or maybe . . .’

‘It’s almost impossible to say,’ Johanne said and frowned.

‘Strangled her until she lost consciousness rather than died, I mean. He must have thought she was dead.’

‘Well, at least we know that the cause of death was strangulation. He must have finished her off with his hands. After he’d cut out the tongue.’

Adam shuddered and added: ‘Have you seen these?’

He fished out a manila envelope and looked at it for moment before obviously changing his mind and leaving it unopened.

‘Just a peek,’ Johanne said. ‘Normally pictures of the scene of the crime don’t bother me. But now, since Ragnhild was born, I . . .’ Tears welled up in her eyes and she hid her face in her hands. ‘I cry for no reason,’ she said in a loud voice, nearly shouting, before pulling herself together and whispering: ‘Pictures like that really don’t bother me. Normally. I’ve seen . . .’

She dried her eyes with abrupt, harsh movements and forced a smile.

‘The husband,’ she said, ‘he’s got a watertight alibi.’

‘No alibi is watertight,’ answered Adam.

Again, he put his hand on her back. The warmth spread through the thin silk.

‘That’s true,’ Johanne said. ‘But as good as. He was at his mother’s with Fiorella. Had to sleep in the same room as his daughter, because his sister and her husband were also staying the night. And on top of that, his sister had a tummy bug and was up all night. And another thing . . .’

She brushed her hand under her right eye once more. Adam smiled and ran his thumb under her nose and then dried it on his trouser leg.

‘And another thing, there’s nothing to indicate anything other than the ordinary marital problems,’ she finished. ‘No relationship problems and certainly no financial problems. They’re fairly equal on that score. He earns more than her, she owns a bigger share of the house. His firm seems to be sound.’

She took his free hand. The skin was coarse and his nails were short. Their thumbs met and moved in circles.

‘And what’s more, eight days have passed,’ she continued, ‘without you finding anything. All you’ve done is rule out a couple of obvious suspects.’

‘It’s a start,’ he said lamely, and pulled back his hand.

‘A very weak one.’

‘What are your thoughts then?’

‘I’ve got lots.’

‘About what?’

‘The tongue,’ she replied and got up to get more coffee.

A car snailed its way down the street. The slow throb of the engine made the glass in the corner cabinet rattle. The beam of light danced about on the ceiling, a moving cloud of light in the big, dark room.

‘The tongue,’ he repeated, despondently, as if she had reminded him of an unpleasant fact that he would rather forget.

‘Yes, the tongue. The method. Hate. It was deliberate. The vase . . .’ Johanne signalled quote marks with her fingers. ‘It was made beforehand. There was no red paper in the house. I saw in your papers that it takes about eight minutes to make something like that. And that’s when you know what you’re doing.’

For the first time, she seemed to be really fired up. She opened a cupboard and took two sugar cubes from a silver bowl. The spoon scratched on the ceramic of the mug as she stirred.

‘Coffee when we can’t sleep,’ she mumbled. ‘Smart move.’ She looked up. ‘Cutting someone’s tongue out is such a loaded symbol, so aggressive and horrific that it’s hard to imagine that it’s motivated by anything other than hate. A pretty intense hate.’

‘And Fiona Helle was loved by all,’ came Adam’s dry retort. ‘I think you’ve stirred the sugar enough now, dear.’

She licked the spoon and sat down again.

‘The problem is, Adam, that it’s impossible to know who hated her. As long as her family, her friends, acquaintances, colleagues . . . everyone around her seemed to like the woman, you’ll have to look out there for the murderer.’

She pointed out of the window. One of the neighbours had turned a light on in the bathroom.

‘I don’t mean them, specifically,’ she smiled. ‘I mean the general public.’

‘Dear God,’ groaned Adam.

‘Fiona Helle was one of the most high-profile TV stars in the country. I doubt there’s many people who don’t have an opinion about what she did, and therefore also about who they thought she was, right or wrong.’

‘Over four million suspects, you mean.’

‘Yep.’

She took a sip of coffee before putting down her mug.

‘You can forget everyone under fifteen or over seventy, and the million or so who really adored her.’

‘And that leaves how many, d’you reckon?’

‘No idea. A couple of million, maybe?’

‘A couple of million suspects . . .’

‘Who possibly have never even spoken to her,’ she added. ‘There doesn’t need to be any direct link between Fiona and the man who killed her.’

‘Or woman.’

‘Or woman,’ she agreed. ‘Good luck. And, looking at the tongue . . . Shhh!’

A feeble cry could be heard from the freshly decorated children’s room. Adam got up before Johanne had time to react.

‘She just wants food,’ he said and made her sit down. ‘I’ll get her. Go and sit down on the sofa.’

She tried to pull herself together. The fear was physical, like an adrenalin shot. Her pulse rose, her cheeks flushed hot. When she lifted her hand and studied her palm, she saw the light from the ceiling reflected in the sweat in her lifeline. She dried her hands on her dressing gown and sat down heavily on the sofa.

‘Is my little munchkin hungry?’ she heard Adam murmuring into the baby’s hair. ‘You’ll get some food from Mummy. There, there . . .’

The half-open eyes and eager mouth made Johanne cry again, with relief.

‘I think I’ve gone mad,’ she whispered and adjusted her breast.

‘Not mad,’ said Adam, ‘just a bit tense and frightened, that’s all.’

‘The tongue,’ mumbled Johanne.

‘We don’t need to talk about that now. Relax.’

‘The fact that it was split.’

‘Shhhh.’

‘Liar,’ she sniffed and looked up.

‘Liar?’

‘Not you, silly.’

She whispered to the child before she met his eye again.

‘The split tongue. Can really only mean one thing. That someone thought that Fiona Helle was a liar.’

‘Well, we all tell a lie now and then,’ Adam said, and gently stroked the soft baby’s head with his finger. ‘Look, you can see the pulse in her fontanelle!’

‘Someone believed that Fiona Helle was lying,’ Johanne repeated. ‘That her lying was so blatant and brutal that she deserved to die.’

Ragnhild let go of the nipple. Something that could easily be mistaken for a smile flitted across her face and Adam knelt down and put his cheek against her damp cheek. The blister on her upper lip from sucking was pink and full of fluid. Her tiny eyelashes were nearly black.

‘It must have been some lie, in that case,’ Adam mumbled. ‘A bigger lie than I could ever make up.’

Ragnhild burped and then fell asleep.

*

She would never have chosen this place herself.

The others, notorious cheapskates, had suddenly decided to treat themselves to three weeks on the Riviera. What you were supposed to do in the Riviera in December was a mystery to her, but she said yes all the same. At least it would be a change.

Her father had become unbearable since her mother died. Whining and complaining and clinging to her all the time. He smelt like an old man, a combination of dirty clothes and poor bladder control. His fingers, which scraped her back when he gave the most unwanted goodbye hugs, were now disgustingly thin. Obligation forced her to visit him once month or so. The flat in Sandaker had never been palatial, but now that her father was living on his own it had really gone downhill. She had finally managed, after many letters, furious phone calls and a lot of bother, to get him a home help, but it didn’t help much. The underside of the toilet seat was still splattered with shit. The food in the fridge was still well past its sell-by date and you couldn’t open the door without gagging. It was unbelievable that the local council could offer an old, loyal taxpayer nothing more than an unreliable girl who had could scarcely turn on a washing machine.

The idea of Christmas without her father tempted her, even though she was sceptical about travelling. Especially as the children were going too. It irritated her beyond reason that children today seemed to be allergic to any form of healthy food. ‘Don’t like, don’t like,’ they kept on whingeing. A mantra before every meal. Not surprising they were skinny when they were little and then ballooned out when they hit their amorphous puberty, ravaged by modern eating disorders. The youngest, a girl of three or four, still had some charm. But the woman with the laptop was not particularly fond of her siblings.

But the house was big and the room they thought she should have was impressive. They had shown her the brochures with great enthusiasm. She suspected they were relying on her to pay more than her fair share of the rent. They knew that she had money, even though they had absolutely no idea how much.

Truth be told, she had chosen not to keep in touch with most of her acquaintances. They scurried around in their small lives, making mountains out of molehills, problems that in no way would interest anyone but themselves. The red figures in her social accounts, which she had eventually decided it was necessary to draw up, screamed out at her. Sometimes, when she thought about it, she realized that she had really only met a handful of people of any merit.

They wanted her to come with them and she could not face another Christmas with her father.

So she was standing at Gardemoen airport, with her tickets in her hand, when her mobile phone rang. The little one, the girl, had suddenly been admitted to hospital.

She was furious. Of course her friends couldn’t leave their little girl, but did they have to wait until three quarters of an hour before the flight was due to depart to tell her? After all, the child had fallen ill four hours earlier. But she still had a choice.

She went.

The others would still have to pay their share of the rent, she made that absolutely clear to them on the phone. She had actually found herself looking forward to spending three weeks with the people who she had, after all, known since she was a child.

After nineteen days down there, the landlord had offered to let her stay until March. He hadn’t managed to find any tenants for the winter and didn’t like the house to stand empty. Of course, it helped that the woman had tidied and cleaned just before he came. He probably also noticed that only one of the beds had been used, as he prowled from room to room, pretending to look at the electrics.

It was as easy to write on her laptop here as at home. And she had free accommodation.

The Riviera was overrated.

Villefranche was a sham town for tourists. In her opinion, any reality that might have been there had disappeared a long time ago; even the several-hundred-year-old castle by the sea looked as if it had been built from cardboard and plastic. When French taxi drivers can speak half-decent English, there has to be something seriously wrong with the place.

It annoyed her immensely that the police had got nowhere.

But then, it was a difficult case. And the Norwegian police had never been anything to boast about, provincial, weaponless eunuchs that they were.

She, on the other hand, was an expert.

The nights had closed in.

III

Seventeen days had passed since Fiona Helle was murdered and it was now the 6th of February.

Adam Stubo sat in his office in the dreariest part of Oslo’s east end, staring at the grains of sand running through an hourglass. The beautifully shaped object was unusually large. The stand was handmade. Adam had always thought it was made of oak, good old Norwegian woodwork that had darkened and aged over hundreds of years. But a visiting French criminologist, who had been there just before Christmas, had studied the antique with some interest. Mahogany, he declared, and shook his head when Adam told him that the instrument had been in his seafaring family for fourteen generations.

‘This,’ the Frenchman said, in perfect English, ‘this little curiosity was made some time between 1880 and 1900. I doubt it has even been on board a ship. Many of them were made as ornaments for well-to-do people’s homes.’

Then he shrugged his shoulders.

‘But by all means,’ he added, ‘a pretty little thing.’

Adam chose to believe in the family story rather than some wayward passing Frenchman. The hourglass had stood on his grandparents’ mantelpiece, out of reach of anyone under twenty-one. A treasured object that his father would turn over for his son every now and then, so he could watch the shiny grains of silver-grey sand in the beautiful, hand-blown glass as they ran through a hole that his grandmother claimed was smaller than a strand of hair.

The files that were piled up along the walls and on the desk on both sides of the hourglass told another, more tangible story. The story of Fiona Helle’s murder had a grotesque start, but nothing that resembled an end. The hundreds of witness statements, the endless technical analyses, special reports, photographs and tactical observations seemed to point in all directions but led nowhere.

Adam could not remember another case like it, where they had absolutely nothing to go on.

He was getting on for fifty. He had worked in the police force since he was twenty-two. He had trudged the streets on the beat, hauled in down-and-outs and drunk drivers as a constable; he considered joining the dog unit out of sheer curiosity, had been extremely unhappy behind a desk in ØKOKRIM, the economic and environmental crime unit, and then finally ended up in the Criminal Investigation Service, by chance. It felt like a couple of lifetimes ago. Naturally, he couldn’t remember all his cases. He had given up trying to keep a mental record a long time ago. The murders were too numerous, the rapes too callous. The figures were meaningless after a while. But one thing was certain and irrefutable: sometimes everything went wrong. That’s just the way it was, and Adam Stubo didn’t waste time dwelling on his defeats.

This was different.

This time he hadn’t seen the victim. For once he hadn’t been involved from the start. He had limped into the case, disoriented and behind. But in a way that made him more alert. He thought differently from the others and noticed it most clearly in meetings, gatherings of increasing collective frustration, where he generally kept shtum.

The others got bogged down in clues that weren’t really there. With care and precision, they tried to piece together a puzzle that would never be solved, simply because the police only found clear blue skies wherever they looked for dark, murky shadows. They had found a total of twenty-four fingerprints in Fiona Helle’s house, but there was nothing to indicate that any had been left by the murderer. An unexplained cigarette stub by the front door didn’t lead anywhere; according to the latest analyses it was at least several weeks old. They might as well cross out the footprints in the snow with a thick red pen, as they couldn’t be linked to any other information about the killer. The blood at the scene of the crime gave no more clues either. The saliva traces on the table, hair on the carpet and greasy, faint red lip marks on the wine glass told a very ordinary story of a woman sitting at her desk in peace and quiet, going through her weekly post.

‘A phantom killer,’ Sigmund Berli grinned from the doorway. ‘Buggered if I’m not starting to believe the grumblings of the Romerike guys, that it’s suicide.’

‘Impressive,’ Adam smiled back. ‘First she half strangles herself, then she cuts out her tongue, before sitting down nicely to die from blood loss. But before she dies, she musters up enough energy to wrap the tongue up in a beautiful red paper package. If nothing else, it’s original. How’s it all going, by the way? Working with them, I mean?’

‘The guys from Romerike are nice enough. Big district, you know. Of course they like to throw their weight around a bit. But they seem to be pretty happy that we’re involved in the case.’

Sigmund Berli sat down on the spare chair and pulled it closer to the desk.

‘Snorre’s been selected for a big ice-hockey tournament for ten-year-olds this weekend,’ he said and nodded meaningfully. ‘Only eight and he’s being selected for the top team with the ten-year-olds!’

‘I didn’t think they ranked teams for such young age groups.’

‘That’s just some rubbish the sports confederation has come up with. Can’t think like that, can you? The boy lives for ice-hockey, twenty-four seven – he slept with his skates on the other night. If they don’t learn the importance of competitions now, they’ll just get left behind.’

‘Fair enough. He’s your child. I don’t think I’d . . .’

‘Where are we going?’ Sigmund interrupted, casting his eye over all the files and piles of documents. ‘Where the hell are we going with this case?’

Adam didn’t answer. Instead he picked up the hourglass and turned it round again.

‘Adam, stop it. Are the sleepless nights getting to you, or what?’

‘No. Ragnhild’s lovely. Nine. Ten.’

‘Where are we going, Adam?’

Sigmund’s voice was insistent now, and he leant towards his colleague and continued: ‘There isn’t a single fucking clue. Not technical at least. Nor tactical, as far as I can tell. I went through all the statements yesterday, then again today. Fiona Helle was well liked. By most people. Nice lady, they say. A character. Lots of people reckon it was her complexity that made her so interesting. Well read and interested in marginal cultural expression. But also liked cartoons and loved Lord of the Rings.’

‘People who are as successful as Fiona Helle always have . . .’

Adam tried to find the right word.

‘Enemies,’ Sigmund suggested.