9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

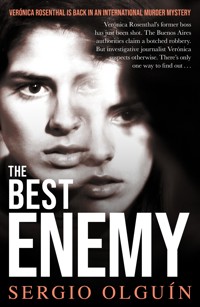

- Herausgeber: Bitter Lemon Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Two foreign girls are murdered after a high society party in Yacanto del Valle, northern Argentina. Their bodies are found in a field near sacrificial offerings, apparently from a black magic ritual. Verónica Rosenthal, an audacious, headstrong Buenos Aires journalist with a proclivity for sexual adventure, could never have imagined that her holiday would end with her two friends dead. Not trusting the local police, she decides to investigate for herself.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

3

THE FOREIGN GIRLS

Sergio Olguín

Translated by Miranda France

5

To Mónica Hasenberg and Brenno Quaretti

To Eduardo Arechaga

6

7

These insurgent, underground groups, the mara wars, the mafias, the wars police wage against the poor and non-whites, are the new forms of state authoritarianism. These situations depend on the control of bodies, above all women’s bodies, which have always been largely identified with territory. And when territory is appropriated, it is marked. The marks of the new domination are placed on it. I always say that the first colony was a woman’s body.

RITA SEGATO, INTERVIEW BY ROXANA SANDÁ IN PÁGINA/12, 17 JULY 2009

One goes in straightforward ways,

One in a circle roams:

Waits for a girl of his gone days,

Or for returning home.

But I do go – and woe is there –

By a way nor straight, nor broad,

But into never and nowhere,

Like trains – off the railroad.

ANNA AKHMATOVA, “ONE GOES IN STRAIGHTFORWARD WAYS” (TRANSLATED BY YEVGENY BONVER; FIRST PUBLISHED IN POETRY LOVERS’ PAGE, 2008)

We are all hiding something sinister. Even the most normal among us.

GUSTAVO ESCANLAR, LA ALEMANA

Contents

Prologue

from: Verónica Rosenthal

to: Paula Locatti

re: Radio Silence

Dear Paula,

This is going to be one long email, my friend. Apologies for not replying to your previous messages nor to your request, so elegantly expressed, that I “stop sending fucking automatic replies”. Originally I intended not to answer any emails during my vacation and anyone who wrote to me was meant to get a message saying I wouldn’t be responding until I got home. But what has just happened to me is shocking, to put it mildly. I need to share it with someone. With you, I mean. You’re the only person I can tell something like this. I thought of ringing you, even of asking you to come, because I didn’t want to be alone. But I also can’t behave like a teenager fretting about her first time. That’s why I decided not to call but to write instead. On the phone I might beg you to come. And, to be honest, there’s other stuff I want to tell you, things I could never bring myself to say in person, not even to you. Written communication can betray our thoughts, but oral so often leads to a slip of the tongue, and I want to avoid that. There’s a slip in the last sentence, in fact, but I’ll let it go. 12

As I was saying, what I write here is for your eyes only. Nobody else must find out what I am going to tell you. Nobody. None of the girls, none of your other friends. It’s too personal for me to want to share it. Come to think of it, delete this email after you’ve read it.

I told you that I was going to start my trip in Jujuy, then go down from there to Tucumán. Well, I didn’t do that in the end. A few days before I set off, my sister Leticia reminded me about the weekend home that belongs to my cousin Severo (actually, he’s the son of one of my father’s cousins). He’s not only a Rosenthal but also part of ‘our’ legal family: a commercial judge in Tucumán. I think he’d love to work in my dad’s practice, but Aarón has always kept him at arm’s length. He’s forty-something, married to a spoiled bitch and father to four children. Anyway, Severo has a weekend cottage on the Cerro San Javier, and whenever he comes to Buenos Aires he insists that we borrow it. I checked and the house was available for the time I needed it, so I decided to change my route: to start in Tucumán, stay a week in Cousin Severo’s house and then go on to Salta and Jujuy. I thought it wouldn’t be a bad thing to spend a quiet week there, resting and clearing my mind after the very shitty summer I’d had.

So I arrived at the airport in San Miguel de Tucumán, picked up the car I’d rented and swung by the courts to see my cousin and collect the keys to the house. I spent half an hour in his office exchanging family news (his eldest son starts law this year – another one, for God’s sake). I graciously declined his invitation to lunch and, with barely suppressed horror, another invitation to have dinner at his house with the wife and some of the four children. He gave me a little map with directions (even though I had rented a GPS with the car – although God knows why, since you can get anywhere just by asking) and a sheet of paper with useful telephone 13numbers and the Wi-Fi code. He told me that a boy came to clean the pool once a week and there was a gardener too, but that they came very early and had their own keys to the shed, that I wouldn’t even know they were there (and he was right, I’ve never seen their faces). He offered to send me ‘the girl’ who lives in their house in the city, but I declined this invitation.

If you saw my cousin’s house you’d go berserk. It’s hidden away behind a little wood on the hillside. A typically nineties construction, Californian style: huge windows, Italian furniture, BKF butterfly chairs (uncomfortable), a Michael Thonet rocking chair which, if it isn’t an original, certainly looks the part, a spectacular view (even from the toilets), a Jacuzzi in almost all the bathtubs, a sauna, a well-equipped gym, huge grounds (looking a bit sparse now that autumn’s on its way), a heated swimming pool, a changing room, a gazebo which is in itself practically another house and lots, lots more. Plus full cupboards, a wine cellar and more CDs and DVDs than you could possibly ever need. Never mind a week, it’s the kind of paradise to hide away in for a year.

And that’s what I’ve been doing. Reading, spending time in the pool, watching movies. Even though there’s Wi-Fi I haven’t gone online; I haven’t watched the news or read the papers. If there had been a coup, a tsunami in Japan or World War Three had broken out, I would be none the wiser.

It feels like a kind of professional and life detox. After spending the summer covering for other people at the magazine who were on leave, writing pieces no one was interested in, and feeling no appetite to get my teeth into a proper story, I needed this: to be far from the relentless noise of the city – no friends, no guys, no family. Nothing. It’s the first time since Lucio died that I’ve been able to spend time 14alone with myself. And I’ve needed it. The summer was hard. I don’t need to tell you that.

A few days ago I decided to go out for a bit. It was still light when I set off in the car with no particular destination. The mountain road in this area is really beautiful, so I was driving along, taking in the view without worrying about anything. After a thousand twists and turns, the road came to a kind of seaside town, like a cool resort: a few pubs, boutiques with hippie clothes, groups of shouting teenagers. The usual.

I stopped at a bar that looked promising and had a parking spot right beside it. Inside there weren’t many people. I sat down at a table near the bar and asked for a Jim Beam. It seems my order caused a stir because, when the glass of bourbon arrived, I noticed some guys on a nearby table were staring at me – them and the barman too. I focussed on my maps and guidebooks. I wasn’t there to flirt with the locals.

Soon after that, two girls arrived. I didn’t actually see them come in and go up to the bar. It was their voices I noticed first. Or rather the voice of one of them who, in very good Spanish but with a foreign accent, asked the barman where they could buy “una cuerda”.

I think it was the word cuerda that got my attention, and I immediately imagined that these two women were looking for rope to tie up some man, not thinking that cuerda can also mean “string”. The barman must have thought something similar, because he asked them “Una cuerda?” in a surprised tone of voice. The foreign girl clarified: “Una cuerda para la guitarra”.

The barman said if they were looking for a music shop they should go to the provincial capital, San Miguel de Tucumán. The other girl asked if they could call a taxi to take them there from the bar. And I, who had been listening as though I were part of the conversation, offered to take them myself.15

I don’t tend to have such quick reactions. And I still don’t know what prompted me to make the offer: whether I was starting to get bored sitting there, or I wanted to talk to someone after so many days alone, or that the fact they were foreign girls prompted a sudden urge to be a good ambassador for my country. Anyway, the girls were happy to accept the offer.

As for what happened next, I’ll be brief. I realize now that the reason I included so many unimportant details in what I wrote before was to put off the most important part, the only thing I really want to tell you. That I need to tell you.

Petra, Frida and I quickly bonded in the way that people who meet while travelling often do. We talked about our lives over empanadas in a restaurant on the edge of town. Petra is Italian, sings and plays the guitar. The other girl, Frida, is Norwegian and spent a year living in Argentina. That was when they got to know each other. And then they made a plan to meet up again to travel together in northern Argentina, Bolivia and Peru.

They both speak perfect Spanish. Frida has a slight Castilian accent because she studied in Madrid. Petra, on the other hand, sounds really Argentinian. She lived in Milan with a guy from Mendoza for more than a year and after that she was in a relationship with someone from Córdoba. Nothing like pillow talk to improve your accent.

On more than one occasion we raised our glasses to all the idiot men who have ruined our lives. My Italian and Norwegian friends would have been right at home on a night out with you and me in Buenos Aires.

We decided to travel on together, at least until we reached the city of Salta (they want to spend a few days there, but I’d rather press on to Jujuy). Yesterday I went to pick them up so they can move into my cousin’s place. There’s plenty of room. 16

The girls are a lot less prudish than me. They sunbathe topless and don’t mind walking naked out of their rooms. I’ve tried to follow suit, at least by going topless next to the pool. They’re two lovely, cheerful girls, a few (but not many) years younger than me.

I’ve realized from one or two things they said that there is, or was, something between them.

Last night we got drunk on some whisky that my cousin is definitely going to miss. Don’t ask me how – or how far – things went, but Frida and I ended up in what you might call a confusing situation.

There it is, I’ve said it.

It was nice, unnerving, exhilarating.

I don’t want any jokes, or winks, or sarcasm from you. Is that possible? Or for you to cling to the edge of the mattress if we end up sharing a bed when we go to the hot springs at Gualeguaychú.

I’m writing all this from my bed (alone, obviously). Midday. I woke up with a crashing hangover. But even so, I remember absolutely everything that happened last night. I still haven’t left the room. There’s too much silence in the house. Ah well.

Kisses,

Vero

*

from: Verónica Rosenthal

to: Paula Locatti

re: Kolynos and the party

Hi Pau,

Thanks. I expected nothing less from you. But your thing doesn’t count. Nothing one does as a virgin can be taken 17seriously. If I told you about the stuff I got up to back then, you’d be appalled.

I’m in Cafayate now. All on my own.

After the last email I wrote you, I showered, got dressed and went into the kitchen. Petra and Frida were there. They were making coffee and didn’t seem to be in a much better state than I was. I mean, they were obviously hung-over too. None of us mentioned the disconcerting experience we’d had a few hours previously. During our last days at the house there were a few histrionics from Frida, too boring to go into details. Nothing worth sharing.

Eventually, we decided to go to the north of Tucumán province. They wanted to head for Amaicha del Valle, but I was keen to stop first at Yacanto del Valle, a little town much closer than that, which I’d been told I should see. We agreed to stay there for two or three nights.

In Yacanto we stayed in a charming hotel run by a couple from Buenos Aires. The girls stayed in one room and I was in the other.

Yacanto is a boutique town. All very cool and fake. Apart from the main square and the eighteenth-century church, everything else is like a kind of stage set put together by city types from Buenos Aires and San Miguel de Tucumán. There are vegetarian restaurants, clothes shops (more expensive even than the ones in Palermo), antique shops; there’s even a contemporary art gallery – whose owner is related to my cousin’s wife and from a traditional Salta family, like her.

I took the girls to the gallery and we met him there. He’s called Ramiro. I already knew a bit about him from my sister, who met him on a trip she made with her husband and the kids. Leti practically drooled when she told me about Ramiro. Knowing my brother-in-law, and Leti’s taste (in all things), 18I was prepared for the worst. But on this occasion my elder sister wasn’t completely wrong.

Ramiro. Roughly my age or possibly a couple of years older, a bit taller than me, broad shoulders, lantern jaw, blue eyes, Kolynos smile, very short hair that left his nape dangerously exposed (bare napes should be banned). And single. This information he offered himself, two minutes into our conversation.

Kolynos behaved like a gentleman. He showed us round his gallery. Nothing too earthy, no indigenous art: there were pieces by artists from the Di Tella Foundation, a Plate, a Ferrari, a couple of Jacobys and work from the eighties and nineties (Kuitca, Alfredo Prior, Kenneth Kemble). The guy has good taste and clearly likes showing it off.

I already know what you’re thinking: run a mile from exhibitionists! You’d equate his artworks, the big house where he has his gallery and his Japanese pickup with the kind of man who flashes at the entrance of a girls’ school. But the only time that ever happened to me I had a good look. I was shocked, but I still looked.

Evidently some methods of seduction don’t work with foreign girls – or perhaps contemporary Argentine art is the problem – because Petra and Frida seemed bored as they listened to Ramiro. I tried to arrange something for that night because I didn’t feel like only being with the girls. Ramiro said he was busy, that he had a lot on. It came across a bit like an excuse. I know what you’re going to say: he sounds like a dick.

Kolynos asked for my phone number, asked if I used WhatsApp – obviously, I said no – and looked at me as though I’d landed from another planet. “I’m an old-fashioned girl,” I added, with a quiet pride.

I could already see myself spending the evening eating tamales with Petra and Frida, then going to get drunk in their 19room or mine. But get this: an hour after we left the gallery, Kolynos called me. He said that there was a party that night at a house on the outskirts of Yacanto, and did the three of us want to go. Obviously I said we did, without even running it by the girls.

Petra and Frida were both happy when I said we’d been invited to a party. I’d almost say I was mildly offended that they were so keen to spend the night with someone other than me. And so…

That evening Ramiro came to fetch the three of us in his pickup and off we went. Why didn’t we walk, since it was only six or seven blocks away? More exhibitionism. It’s true that the house was on the outskirts of town, but that’s because Yacanto is only five blocks long.

We arrived. A big-ass country house with music blaring out and people dancing and holding glasses. It looked like a beer ad.

To start with the girls stuck by me, something I wasn’t thrilled about. Kolynos was very gallant. We danced, we chatted, we strolled around the garden. All very proper.

He introduced me to the owner of the property, a certain Nicolás. Also single. I marvelled at the size of his house and the idiot started boasting about the huge estate that surrounded it. As Mili would say: good game, terrible result.

We were still with Nicolás when a group of offensively young twenty-somethings turned up. One was a dreamboat – bronzed, sub-twenty-five. You’d have loved him. “My little brother, Nahuel,” Kolynos said by way of introduction. Well, that was a surprise. Immediately I thought of Leti, who had recommended the older brother without mentioning the younger one. Either she hadn’t met him, or she considered me far too old for such a morsel. Anyway, full disclosure: Nahuelito barely registered me and didn’t have much time 20for his brother either. He started talking to Nicolás and we moved away from the group.

At one point it seemed to me that Petra was annoyed about how Frida was treating me, or about something, anyway. For some reason the Italian kept freaking out at Ramiro or any other man who came her way (and a lot did).

A lot of alcohol later, I ran into Frida coming out of the bathroom (was she waiting for me?) and she told me that she wasn’t enjoying the party at all. I asked where Petra was and she pointed at the dance floor. That was when I realized that these two were a couple of drama queens who got off on making each other jealous and wanted to stick me in the middle. She didn’t like Ramiro either, she said. I laughed and she got annoyed. I made it clear that I was planning to leave with Ramiro and that she should go and have fun with other people. Before she had a chance to answer, I was already walking away.

Soon afterwards, Ramiro took me upstairs. He kissed me and suggested we go to his house. I told him that I was with the girls and couldn’t leave them alone. He said that I shouldn’t worry, that they could walk back to the hotel if they couldn’t find anyone to take them back, but that he suspected they wouldn’t be leaving alone. They could even sleep over here, at the house.

Long story short, I went home with Señor Kolynos. We had a good time. The next morning I felt a bit awkward. Not about him, but about the girls. I felt as though I had betrayed them. A stupid reaction, because the last thing I needed was to be giving them chapter and verse on everything I did or didn’t do. I got angry with myself. I went to the hotel, packed my case, paid the bill and left. I was going to leave a note for the girls but that felt like giving explanations, something I wanted to avoid.21

At 8 a.m. I set off for Cafayate. I’ve just arrived. I’m in a really pretty hotel. The owner, yet again, comes from Buenos Aires. Have I really travelled eight hundred miles to meet people from Buenos Aires?

This place is beautiful. I’m going to enjoy the provincial peace. I’m sorry about leaving the girls, but I needed some space. I’ll write them an email. Perhaps we can meet up in Salta, or in Jujuy itself. Yes, I know, I’m impossible to please. It’s only half a day since I saw them and already I miss them. I’m going to wait for them here.

Kolynos? He was a summer storm. Not even that. I don’t think we’ll see each other again.

V.

*

from: Verónica Rosenthal

to: Paula Locatti

re: Re: Kolynos and the party

The girls are dead. Petra and Frida. They killed them, raped them, treated them like animals. It was after the party. I’m to blame for all of it, everything that happened to them. If I hadn’t left them there, they’d be alive. Yesterday the bodies were found lying in some undergrowth. Why the fuck did I leave them alone? I’m going back to Yacanto del Valle. I’m going to find out who the bastards were. I swear if I find them first I’ll kill them. I’ll tear them apart.22

1 New Moon

I

Flying made her sleepy. Any time she had to take a long flight, she slept for a large part of the journey and only woke up to eat or go to the bathroom. People must think she took sleeping pills, but it was just the way she was. She couldn’t even stay awake on a two-hour flight like the one she was on now to Tucumán. Only the shudder of the plane as it touched down at Benjamín Matienzo airport made her open her eyes. Verónica stretched and looked out of the window at the other planes on the ground, the trailers stacked with suitcases and the airport workers moving around.

After collecting her luggage, she went to the car rental office. She had reserved a Volkswagen Gol to take her as far as Jujuy. A small and practical car. In Buenos Aires she made do with borrowing her sister Leticia’s car every now and then, because she didn’t like driving in the city, but the prospect of a journey through Argentina’s north without having to rely on buses and timetables, taking back roads and stopping whenever she liked, was appealing enough to persuade her to hire a car.

The rental company employee asked her name. 24

“Verónica. Verónica Rosenthal.”

Together they walked to the parking lot. The employee made a note in the file of a couple of scratches on the body-work, showed her where the spare wheel was and how to remove it, reminded her that she must return the car with a full tank and finally handed over the keys and relevant documents.

Verónica switched on the GPS she had rented along with the car and entered the address of her cousin Severo’s house in the centre of San Miguel de Tucumán. She lowered the window and felt the breeze on her face, in her tousled hair. A kind of peace swept through her body.

She hadn’t felt like this for a long time. During the last few difficult months there had been only one objective: to get through the day. She had been like a patient in a coma, except that she walked, she talked, she got on with her job. She didn’t want anything, seek out anything, need anything. She tried not even thinking. How long could she have gone on like that?

Verónica’s colleagues at the magazine, her family and friends would have had no hesitation in describing her as a successful journalist. When she had started working in journalism it had been with the dream of exposing corruption, injustice, lies. She had been not quite twenty with everything ahead of her, both in her own life and in the wider world. If someone had told her then that at the age of thirty she would take down a criminal gang that gambled on the lives of poor children, she would have been proud. That was exactly the kind of journalism she wanted to do. And she had done it. She had put a bunch of men behind bars who were responsible for the death and mutilation of boys. She had exposed and eliminated a gambling racket that nobody had investigated before her. No kid would ever again stand on a 25train track waiting for ten thousand tons of metal to come thundering towards him. But she had also paid a price she had never imagined: Lucio, the man she loved, had been killed, a victim of the same mafia.

She had published her article while her grief over Lucio’s death was still raw. The repercussions were such that, in the days following the publication of her piece in Nuestro Tiempo, she had been expected to appear on various television and radio programmes. She had given the requisite answers to her colleagues’ questions, smiled at the end of every interview and thanked them for inviting her on. How could she have told them the truth? How could she put into words the anguish of knowing that one of her informants, Rafael, had so nearly been murdered? What would have happened if one of those condescending colleagues had asked what she had done to save the lives of Rafael and the doorman of the building where she lived? She could have answered: It wasn’t easy. I had to commandeer a work colleague’s car to get there in time. I found four professional assassins about to slay Rafael and Marcelo and had no option but to drive into them. Run over all four of them.

The journalist would have considered this with an expression of utmost compassion. They would have asked how she had felt at the moment she crushed the assassins.

Relief, knowing that two people I loved weren’t going to die at the hands of those brutes.

But nobody would ask those questions, nor did she want them to. She preferred the generous silence her boss and her colleagues had brought to the reporting of her article. The fearful silence of her father and sisters. The complicit silence of her friends. The critical silence of Federico.

She had spent the summer going between the newsroom and home, home and the newsroom. Knowing that her colleagues with children preferred to take their vacations 26in January and February, she had asked for leave in March. She spent much of the summer helping Patricia, her editor, writing twice as many lifestyle pieces as usual, filling pages. The bosses would be happy.

For some time Verónica had been thinking of making a trip to the north of Argentina. She had been to Jujuy with her family as a child but didn’t remember much about it. It was her sister Leticia who had said she ought to go to their cousin Severo’s weekend house. Strictly speaking, Severo Rosenthal was the son of a cousin of their father’s who had moved to Tucumán decades earlier. Severo had studied law at the Universidad Católica Argentina in Buenos Aires, and during those years her parents had treated him like a son: he often went to eat at the Rosenthal home; some nights he even stayed over. Verónica would have been not yet ten at the time.

After he graduated, Severo worked for a time at Aarón Rosenthal’s law firm, but soon afterwards he returned to Tucumán. Supposedly he was going back to the provinces to do what he eventually did: forge a career in the provincial courts. But when Aarón talked about his cousin’s son he often said that he had “got rid of him” because he was “slow on the uptake”. Whatever the truth, Severo was now a commercial judge. He had married, had children. And along with these accomplishments he had acquired a spectacular weekend house that was every now and then at the disposal of the Buenos Aires Rosenthals, perhaps to repay them for the many meals they had shared with Severo in his student days.

When Leticia found out that Verónica was planning a trip to Tucumán, Salta and Jujuy she urged her to spend a few days in that house. She also gave her two other instructions.

The first was “Steer clear of the Witch.” That was how she referred to Severo’s wife, Cristina Hileret Posadas, who was from a traditional northern family. The Rosenthal sisters 27had never liked her, not that they considered Severo a great catch or anything. But to fall into the clutches of someone so bitter, bilious and pessimistic, whose only redeeming feature was having family money, struck them as a terrible fate – even for Severo.

Her second piece of advice was this: “You should definitely visit Yacanto del Valle. The town is really pretty. Plus the Witch has a cousin who lives there, and he’s hot.”

For the first time in many years, Verónica was considering following her older sister’s advice.

II

She wasn’t used to driving on mountain roads, so she couldn’t enjoy the views as she climbed the road that led to her cousin’s house in Cerro San Javier. And even though her cousin had given her the GPS coordinates as well as a map with directions, she was convinced she was going to get lost. But here she was: in front of the gate to The Eyes of San Miguel, as the property was called, a name that Verónica found unnerving, to say the least. That a Rosenthal should give his house the name of a Christian saint was already controversial. She understood the choice better when she parked the car and walked round to the property’s back entrance. From that vantage point there was a spectacular view of the city of San Miguel de Tucumán, nestled in a valley in the distance. Closer were the hills of the San Javier sierra, dotted with big houses similar to her cousin’s.

She took off her sandals and sat on the edge of the swimming pool with her feet in the water. For a while she took in the view, feeling the afternoon sun draw a light sweat onto her elephant-grey Tommy Hilfiger T-shirt. There was still heat in these end-of-summer days.28

With wet feet, Verónica walked from the garden to the back door of the house. She opened the door and disconnected the alarm. Despite having assured Severo that she would put it on every time she left the house, she didn’t plan to reconnect it until the last day. She hated alarms in houses, cars or on telephones.

She took her suitcase and bag out of the car and dropped them on the living-room floor. The house smelt of hardwood, cinnamon and spices. Verónica was amazed by the living area with its inviting Italian armchairs and wall-mounted fifty-inch television. A shelving unit covered all of one wall but wasn’t stuffed with books: spaces had been left for artistic objects. Some pieces of furniture seemed to have been bought in antique shops. A Tudor-style cupboard, two BKF chairs, a Louis XV sideboard, a Thonet rocking chair. The eclectic mix of antique and contemporary pieces worked well in this house with its picture windows, with its fireplace in one of the few walls that didn’t have a window onto the garden. Was the Witch responsible for the decor? Were these pieces inherited from her family in Jujuy and Salta? Could she have bought them from some neighbour in need of ready cash? Stolen them? When it came to the Witch, anything was possible.

The kitchen was stunning, with an extraordinary variety of appliances Verónica had never even known existed. The island with its lapacho-wood counter was larger than the table in her place in Villa Crespo. The kitchen alone was bigger than her apartment.

There was more food in the larder than you’d find in a bunker designed for surviving a nuclear attack. And there were two fridges. One of them was all freezer, in fact, and packed with frozen food. Cousin Severo had gone out of his way to save her the trouble of visiting a supermarket.29

Verónica looked around the rest of the house, trying to decide which bedroom she was going to sleep in. She crossed a room with a pool table, a drinks cabinet and a cupboard containing a box of cigars. The room smelled of good tobacco.

Finally she settled on a room with a double bed and an en-suite bathroom boasting a Jacuzzi and more enormous windows. It particularly amused her that she could sit on the lavatory, pissing or shitting while contemplating the horizon. It seemed like the strangest thing ever – but she liked it.

III

There was Wi-Fi in the house, but Verónica barely used it. The automatic reply set up on her account was the perfect alibi not to keep on top of emails. She didn’t really feel like surfing the internet, either. She’d rather read, or watch movies. She had brought some books with her (Laure Adler’s biography of Marguerite Duras, Murakami’s 1Q84 and Ernest Hemingway’s Complete Short Stories). She had begun 1Q84 with great enthusiasm, but had been losing interest and finally decided to abandon the novel after finding the language used in erotic scenes too medicalized. Perhaps the problem was with the translator, rather than the Japanese author.

Her cousin Severo’s library had stopped expanding sometime in the 1970s but was very good all the same. He had an almost complete collection of Emecé’s Great Novelists series. She was surprised to find Informe Bajo Llave by Marta Lynch, an author she had never thought of reading. She found the novel, with its story of a writer in love with a military man during the dictatorship, both dark and passionate. She had also selected a Ken Follett novel and Graham Greene’s Dr Fischer of Geneva for her vacation reading.30

The DVD collection contained many movies Verónica had never seen. Unlike most of her friends, she wasn’t a cinephile, but she liked going to the cinema and watching the odd movie on television. She wasn’t partial to any particular era or style of movie, so her cousin’s giant screen was able to tempt her with such offerings as All About Eve, that classic story of ambition and treachery. It was the first time she had seen a whole Bette Davis movie, and Verónica thought her the most wonderful actress ever to appear on screen. She also watched All That Jazz (the alphabetical organization of the DVDs guided her choices), GoodFellas, Ginger & Fred, In the Name of the Father and 2001: A Space Odyssey.

She never got up before eleven, and then the first thing Verónica did every morning was make herself coffee with the Nespresso machine. That said, she usually suffered a brief episode of insomnia at around 7 a.m. She woke up feeling anxious, as though some forgotten nightmare had left shards in her brain. Perhaps it was simply that she wasn’t used to the birds’ dawn chorus. She got up, had a piss, smoked a cigarette and read her Duras biography by the light of the bedside lamp (she didn’t want to open the curtains yet). Half an hour later she was fast asleep again, and those extra three hours of sleep were restorative.

Verónica would take her coffee and cigarette to the veranda, along with whatever book she was reading, and stay there until after noon. Then she connected her iPod to the music system speakers, made a sandwich or a salad, opened a beer and put on the television. No news bulletins or gossip programmes. Verónica preferred those reality shows where couples swapped their homes, a chef explored the gastronomic possibilities of insects from Burundi, a badly behaved dog was retrained, a woman with a crane hijacked a car or a policeman transformed himself into a rock star.31

It was always past three by the time she swapped her T-shirt and underwear for a bikini and headed off for the pool. Even though the house was distant from its neighbours and the pool shielded from view, she didn’t dare swim naked. Around the pool, there were some exceptionally comfortable loungers for lying on and drifting off to sleep. She couldn’t read in the sun – had never liked it. Every so often, then, she went to sit in one of the armchairs on the veranda and read more of her book. When it started getting dark she filled a thermos with hot water and made herself a maté. She defrosted some bread, took a jar of dulce de leche out of the fridge and carried the whole lot back to the recliners on the deck. Normally she wouldn’t have allowed herself bread with dulce de leche, but this was a vacation. No sugar in the maté – she liked it bitter.

Verónica could easily spend a couple of hours there. After eating the bread, and when there was no more water in the thermos, she gazed off into the distance. That was the best moment for her. She let her mind empty, stared at the horizon, the distant houses, the mountain greenery. She listened to the sound of birds and parrots as the air filled with a sweet perfume. A light breeze gave her goosebumps. There was nothing in her head. All thoughts, feelings, fears and anxiety completely disappeared. If she had been dead and a part of nature, a jumble of cells scattered through this landscape, she would have felt no different.

It was usually dark by the time Verónica went back into the house. She had a hot shower (she couldn’t stand to wash with cold water, even in summer), dried her hair, which had not been cut for nearly six months, and put on pants and the T-shirt she slept in. With the television or her iPod on in the background, she uncorked a bottle of wine first, then heated up a pizza, put some absolutely delicious frozen Tucumanian 32empanadas in the oven, or boiled some German sausages, which she ate with sauerkraut from a jar. When her supper was ready, she put it on a tray to eat in front of the television, with that night’s choice of movie.

She never drank more than half a bottle of wine. In the study where the spirits were kept, she had searched unsuccessfully for a bottle of Jim Beam. There wasn’t any – no Jim Beam Black and no Jim Beam White. But cousin Severo had a nice selection of British whiskies.

This is no time for dogmatism, Verónica told herself, picking up a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Label. Between Scotch and nothing, I prefer Scotch.

She finished the movie drinking whisky and smoking, then, half asleep, made her way to her room. Sometimes she would read for a bit longer, other times she would collapse straight into the unmade bed. Right away she would fall asleep and keep sleeping until insomnia struck again at seven o’clock the following morning.

That was how Verónica spent the first five days. On the afternoon of the sixth she got bored and decided to leave the house. Coincidentally, her stash of cigarettes was running low.

IV

It was the first time Verónica had got properly dressed since arriving in Tucumán. Her jeans felt rough against her skin. She had very quickly got used to life in the great outdoors. She thought of putting on a shirt she had bought shortly before leaving which had struck her as perfect for the trip but, looking at herself now in the mirror, it seemed very formal. Instead she opted for a DKNY T-shirt in pastel colours and put a light blue jacket over it. The weather was getting cooler. 33

Instead of taking the road by which she had come from San Miguel de Tucumán, Verónica decided to keep driving up through the hills. She had noticed that the route was almost circular and that, if she kept following it, she would arrive at the provincial capital. The aim was to find a bar before she reached the centre of town. She drove along, enjoying the mountain road, absorbing as much as she could of the view without taking her eyes off the winding road, its ups and downs. As the road finally levelled out and became straighter, she passed a neighbourhood of weekend homes. In the distance she saw a sign advertising a bar called Lugh, which seemed to have the vibe of an Irish pub. The availability of a free parking space right in front of it was enough to persuade her to stop outside, although, on closer inspection, it looked less like a happening pub and more like a typical small-town bar.

There weren’t many people in Lugh and very few of the tables were occupied. There was a couple, a group of four men, and a family of two adults and two pre-teens who were sitting at one of the tables outside. She asked the waitress for a double Jim Beam Black and a still mineral water on the side. For a moment she sensed that the four men, who were sitting alone at a table at the other end of the bar, were watching her. The barman also watched her as he poured the bourbon. Verónica pretended not to notice, turning her attention instead to the map of Argentina’s north-east she had brought with her. It was time to relinquish the sepulchral peace of her cousin’s house and continue north. She would pass through Yacanto del Valle, meet that relative of her cousin-in-law; he’d be a charming guy, she’d fall in love with him and spend the rest of her life in the little town.

Admittedly the plan had some flaws: she wanted to reach Humahuaca and couldn’t let a man detain her en route. 34Perhaps she could take him along with her, though. Settle down together in some other little town. But even if this guy turned out to be a perfect combination of Clive Owen, Rocco Siffredi, nineties Arno Klasfeld and Leonard Cohen at any point in his life, it wouldn’t be enough to tempt her away from Villa Crespo, her beloved neighbourhood in Buenos Aires. So she might as well quickly abandon the fantasy of staying in Yacanto del Valle.

Verónica had already finished the water and drunk half the bourbon when two girls entered the bar. Absorbed in the map, she didn’t notice them come in, only becoming aware of them when one of them asked, in Spanish with inflections of German or Russian or something similar, “Good afternoon, where can we get some rope?”

You could tell straight away that they were foreign, especially the blonde, who had a Nordic look and was wearing military-style trousers with lots of pockets, a black vest and lace-up boots. The other one could have passed for Argentine with her slightly curly black hair, bone-coloured shorts, flat strappy sandals and a loose T-shirt with some writing on it that Verónica couldn’t make out.

The question sounded absurd. What did two foreign girls want with a length of rope? She stared at them with the same expression as the barman.

“It’s for a guitar,” the blonde girl clarified.

The barman told them that they would have to go to the city. He looked in a telephone directory for the address of a specialist shop and mentioned that it was about to close. The dark-haired girl asked if they could call a taxi from the bar. Verónica listened to the whole exchange and thought nothing of offering to take them herself.

Frida and Petra had come into her life a few seconds earlier, when Frida first spoke. Now she was the one entering 35into the destiny of the Norwegian and Italian girls. They looked at each other and all three felt a connection. They exchanged smiles, never suspecting that they were already moving towards a tragedy. Days later, Verónica would keep revisiting, tirelessly, each moment they had spent together, and would alight on various things that she wished she could change, but she would never regret speaking to them in that lost wayside bar.

By the time they arrived in San Miguel de Tucumán some minutes later, they had already told each other a bit about themselves. Frida was a sociologist with a doctorate titled “Migrations and Social Change in the Suburbs of Buenos Aires between 1950 and 1990”. Her studies had brought her to Argentina on various occasions. Petra was a music teacher and an amateur singer-songwriter. Petra and Frida had first met in Córdoba two years previously. At that time Petra was living in San Marcos Sierra and about to separate from her Córdoban boyfriend. Frida had moved to Buenos Aires to work on the final part of her thesis. Petra made several trips to the capital to visit Frida, who returned to Oslo a few months afterwards. Petra went to visit her there. Together they had travelled through the Norwegian fjords, then Sweden and Denmark. They had visited other parts of the European continent too. But Petra didn’t want to stay there. Her new corner of the world was Córdoba: “I’m an orphan, I have no siblings, no aunts or uncles. And the mountains of Córdoba remind me of Piedmont, which is where my paternal grandparents were from. I feel at home in the San Marcos Sierra.”

While travelling through the Norwegian fjords, Frida and Petra had promised each other to visit the ruins of the Incan Empire. They would start in the north of Argentina, travel through Bolivia and then on to Peru. They were at the start of that adventure now.36

Verónica briefly described her work and home life. When the other two pressed her on her love life, she told them only that she had been dating a married man and that it was over now.

“Good thing too. Married men are the worst.”

She didn’t tell them that Lucio had been killed or about the circumstances of his death. Nor any of what she had been through at the end of the previous year. Why would they want to know? When it came down to it, Verónica was exactly as she must have appeared to them: a friendly girl.

They arrived at the music shop just before it closed, then decided to get something to eat. A colleague of Verónica’s from the magazine had recommended a wine bar where they served the best Tucumanian empanadas and tamales to die for. The GPS said it wasn’t far, so they headed for Lo de Raúl, a traditional bar full of families. That night there was no show. From the loudspeakers came the voice of folk legend Atahualpa Yupanqui:

I went to Taco-Yaco

To buy a Spanish steed

And I came back with a little bay

A snoring, skinny low breed

They ordered empanadas, tamales, humita and red wine. Deciding against the house wine, they asked for a bottle of Finca Las Moras. Over coffee they polished off a second bottle.

Petra told them how she had broken up with her Argentinian boyfriend, also a music teacher, prompting Frida to observe, as though she were writing a sociology paper about the local male, “All Argentine men are liars. I don’t know a single man in this country who hasn’t lied to his wife at least once.”37

“Not to sound overly patriotic or anything, but I don’t think lying is exclusive to Argentinians.”

“Or to men,” Petra added.

“Sorry, girls, no. I’ve met men from all over and none of them is like the Argentine male. He reels you in, he gives you a lovely present, all beautifully wrapped and with a ribbon on top. And inside is a big fat lie. Greek mythology talks about the sirens. In this country they should talk about the Argentine male: deceptive, charming – I won’t deny it – but incapable of honesty. Even the Uruguayans are better!”

“Hey, that’s going too far.”

Verónica wanted to know if her knowledge was based on some specific romantic disappointment.

“Well, obviously I went out with some Argentinians. A European woman on her own in Argentina is going to end up in the bed of a local male at some point. They talk to you, they whisper sweet nothings. They work so hard to seduce you, as though their lives depend on it.”

“They put their backs into it.”

“Their backs?”

“They make an effort.”

“Right – they put their backs into it. And you fall for it like a sailor on the Aegean in Homeric Greece. You end up in their bed. And it takes a while for you to realize that they aren’t men, they’re more like mermen.”

“What, fish?”

“No, I mean like sirens. A lot of singing, no substance.”

“You’re exaggerating.”

“Just look around the table: you used to go out with a married man. Petra got cheated on by her little music maker. I’ve had men tell me they’d move to Norway for me.”

“And why not?”38

“Nobody in their right mind wants to go and live in Norway! It’s all talk. They think they’re Borges. But at least Borges really did have a passion for Nordic countries.”

The bar had a patio with no tables, which smokers could use without having to go out into the street. Petra and Verónica went there for a cigarette and Frida accompanied them so as not to wait alone inside. It was a moonless night, quite cold. There were vines on a trellis above the patio from which a few bunches of grapes still hung. The attenuated sound of music and chatter reached them from inside the bar. The women smoked in silence and Frida looked around at the trees and the vines as though searching for something.

“I always feel that nature’s hiding something.”

“Men lie, nature hides. Nothing’s safe.”

“No, no. I mean that it’s hiding something supernatural. I’m an animist. I believe that there are spirits in the branches, in those vine leaves. We’re surrounded by ethereal beings.”

“Ah, la piccola Frida and her childhood full of Viking legends,” said Petra, going over to her friend and smoothing her hair as though they were mother and daughter.

Frida let her do it, like a good girl, then moved her hand to Petra’s face and stroked her cheek. A brief but unmistakable gesture. It was dark and Verónica couldn’t see how they were looking at each other, but she intuited there was something more than friendship between the two women.

Back at the table, they decided not to drink any more – since Verónica had to drive – and ordered coffee. While they were waiting for the bill, the girls suggested that she join them on their journey to Bolivia and Peru. Verónica thought this over for a moment: it wasn’t a bad idea, although she would prefer to stick to her original plan and not go further north than Jujuy, but they could at least travel that far together. 39She accepted and immediately invited them to stay at her cousin’s house, an idea that delighted them both.

She dropped them off at the door of their hotel and they agreed that she would return to pick them up the following day, before lunch. Then Verónica returned alone to Severo’s house. The road was completely dark. She could see only what was illuminated by her car’s headlights. The alcohol was beginning to disperse through her body. She felt strange. All the same, she arrived safely at the house in Cerro San Javier and stayed outside in the garden for a little while. A year ago Verónica would never have invited two strangers to come and stay in her house. But the last few months had taught her that worthwhile things were often to be found somewhere unexpected. When it came down to it, if she had chosen to be a journalist it was because she felt a particular kind of adrenaline when confronted with something unknown. To seek out the unknown was to know it. And she was a full-time journalist, even on vacation.

V

“Klar som et egg,” said Frida, appearing in the living room in a bikini. Verónica looked to Petra for a translation, but the Italian shrugged her shoulders. “I’m as ready as an egg,” Frida said, in Spanish. Verónica and Petra stared at her expectantly. “As ready as an egg to go outside. That’s what we say in Norway.” And without waiting for them she went down to the decked area by the pool. Petra and Verónica followed her.

They had arrived at the house less than an hour ago, carting their rucksacks and a guitar. Verónica had given them a little tour of the house and the girls had seemed enthralled by every discovery: the spectacular view of the garden, the 40larder, the drinks corner, the pool table, the bedrooms with en suites, the Jacuzzi in every bathroom. Verónica had invited them to take their pick of bedrooms (and was careful not to say anything else). She was surprised when they opted for separate rooms. They left their luggage there and went to the veranda. Verónica brought out three open Corona beers. They sat and looked out over the landscape, smoking and drinking.

“This is much more amazing than I’d imagined,” said Petra.

“Exactly how I felt when I arrived a week ago.”

“Is your cousin single?”

“He’s married and very boring.”

“Shame.”

They finished the beers and decided to get changed and go and sunbathe.

When Verónica came out of her room, Petra was in the living area looking at the CDs and sound system. She was wearing a pink, orange and yellow bikini that accentuated her brown skin.

“Which part of Italy are you from?”

“I was born in Turin, but my father’s family was from Villadossola and my mother came from Sicily. My parents met at university. They were both psychologists against shutting people away in asylums, believing in the principle of no one being truly ‘normal’: Da vicino nessuno è normale. They were two amazing people. They died when I was twenty. An accident on the Milan–Turin freeway.”

“How awful.”

“Yes, it was. I was studying at the Conservatory. I thought of giving it all up. But then I changed my mind. I got my degree and left Italy. I don’t think I could live there again. Too much sadness.” 41

Frida appeared, said something in Norwegian and the three of them went outside to lie in the sun. Each settled onto her lounger. Petra and Frida both took off their bikini tops. Verónica stared at them.

Petra smiled back. “You’ll get tan lines.”

“It’s just that I feel like someone’s watching us.”

“So what if they are?”

Verónica felt a bit foolish. Or worse: prudish. She took off her top and dropped it down by the lounger.

Verónica watched Frida put sunscreen on her hands then, rather than rub it into her own body, walk over to Petra and start to spread the lotion over her back. Petra murmured something Verónica couldn’t hear. Verónica decided it was better to lie back and not keep ogling them like a voyeur.

“You should put some cream on.”

“Yes, I should.”

“Turn over and I’ll do your back.”

Verónica did as she was instructed.

“I’ll warm it in my hands first so it doesn’t feel too cold.”

She felt Frida’s hands sweeping over her back. Softly, from her shoulders to her waist. It was what she had been needing: to be touched. She closed her eyes. Some horrible music was playing in the distance, perhaps that summer’s hits. Closer, she could hear cicadas and her own breathing. She didn’t want this moment to end. She wanted to go to sleep feeling Frida’s hands on her skin. In this sleepy state, she heard Frida’s voice.

“Right, time for one of you to do some work.”

Verónica turned her head and saw Frida lie face down on her lounger and Petra pick up the bottle of sunscreen. She closed her eyes again and seemed to hear Petra’s hands sliding over Frida’s back. 42

VI

That evening she received an unexpected call. Apart from her sisters, nobody had been in touch with Verónica since she arrived in Tucumán. So the sound of her phone ringing took her by surprise. She didn’t even remember where she had left it. When she found it, she saw Federico’s name on the screen.

And at that moment, it stopped ringing. It was strange for Federico to call her. He knew that she was on vacation – she had told him by email a few weeks before setting off. They didn’t often write to each other anyway. Although they had spent last New Year’s Eve together, with members of her family, Verónica had gone to spend the night at her father’s house. Her sisters were also going, with their husbands and children, along with some of her father’s friends. And of course they had invited Federico, the most promising lawyer at the Rosenthal law firm, a junior partner, the son that Aarón Rosenthal had never had and the man everyone, including her father, sisters and even nieces and nephews (who, egged on by their mothers, called him “uncle”) wanted to see her marry. Her sisters knew that there had once been something between them and that it hadn’t come to anything, a detail that seemed not to strike them as important. Her father must have made Federico a partner on professional merit; even so, Verónica suspected that her father’s gesture was something like an advance on the dowry he would hand to Federico if he ever managed to trap her and whisk her off into a mixed marriage. Because, as long as they could see her married, it didn’t matter too much to her father and sisters that Federico was a goy. Her father hadn’t given up hope that his star lawyer might have Jewish ancestry. He had said as much to Verónica at one of their lunches at Hermann (“Córdova is a Jewish 43converso surname”) and added, with that smile so typical of the Rosenthals when they knew themselves to be in the right, “I’ve done my homework.”

In truth, Federico Córdova’s parents were from Argentina and his grandparents – from Seville and Galicia – were as Catholic as the Macarena and the Virgen del Monte. Both sets of grandparents had made the same immigrant journey. They had arrived in Argentina with nothing and built a life for themselves and their children. One of Federico’s uncles had risen to the rank of judge in La Plata. He was the one who had offered to organize an internship for Federico at one of the capital’s courts or at the law firm that belonged to his friend: Doctor Aarón Rosenthal, an eminence in the legal world. Federico had opted for Rosenthal and Associates.

It was the best decision of his life because it meant he’d met her, Federico told Verónica after the first time they’d fucked – right afterwards, in fact, because, in contrast to what many people say about men, Federico loved post-coital chat. And while Federico told her his story, and that of his parents, uncles and aunts and of his immigrant grandparents, Verónica was thinking that this had been a mistake, that sleeping with Federico was practically incest. Because ever since they had first met at her father’s firm, they had enjoyed a friendly camaraderie; they were more like siblings than friends. And if she had led him on … well, it wouldn’t be wrong for her to do that. At the end of the day he wasn’t actually her brother.