7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

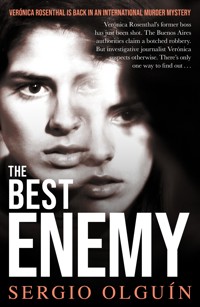

- Herausgeber: Bitter Lemon Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

When she hears about the suicide of a Buenos Aires train driver who has left a note confessing to four mortal 'accidents' on the train tracks, journalist Veronica Rosenthal decides to investigate. For the police the case is closed (suicide is suicide), for Veronica it is the beginning of a journey that takes her into an unfamiliar world of grinding poverty, crime-infested neighborhoods, and train drivers on commuter lines haunted by the memory of bodies hit at speed by their locomotives in the middle of the night. Aided by a train driver with whom she has a tumultuous and reckless affair, a junkie in rehab and two street kids willing to risk everything for a can of Coke, she uncovers a group of men involved in betting on working-class youngsters convinced to play Russian roulette by standing in front of fast-coming trains to see who endures the longest.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Sergio Olguín was born in Buenos Aires in 1967. His first work of fiction, Lanús, was published in 2002. It was followed by a number of successful novels, including Oscura monótona sangre (Dark Monotonous Blood), which won the Tusquets Prize in 2009. His books have been translated into German, French and Italian. The Fragility of Bodies is his first novel to be translated into English, and is the first in a crime series of three novels featuring journalist Veronica Rosenthal. Sergio Olguin is also a scriptwriter and has been the editor of a number of cultural publications.

THE FRAGILITY OF BODIES

Sergio Olguín

Translated by Miranda France

BITTER LEMON PRESSLONDON

BITTER LEMON PRESS

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by Bitter Lemon Press, 47 Wilmington Square, London WC1X 0ET

www.bitterlemonpress.com

First published in Spanish as La fragilidad de los cuerpos by Tusquets Editores Argentina, Buenos Aires, 2012

Bitter Lemon Press gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the Arts Council of England

Work published within the framework of “Sur” Translation Support Program of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Worship of the Argentine Republic

Obra editada en el marco del Programa “Sur” de Apoyo a las Traducciones del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto de la República Argentina

© Sergio Olguín, 2012

Published by agreement with Tusquets Editores, Barcelona, SpainEnglish translation © Miranda France, 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher

The moral rights of the author and the translator have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All the characters and events described in this novel are imaginary and any similarity with real people or events is purely coincidental

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978–1–912242–191

eBook ISBN 978-1-912242-207

Typeset by Tetragon, London

Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman Ltd. Reading, Berkshire

To Gabriela Franco, Natalia Méndez and Pablo Robledo

The complete truth about someone or something can only be told in a novel.

STEPHEN VIZINCZEY,

THE MAN WITH THE MAGIC TOUCH

[…] structural weaknesses in all fields, considerable fundamental disadvantages: technical and economic backwardness, a society dominated by a minority of exploiters and wastrels, the fragility of bodies, the instability of a rough sensibility, the primitivism of logic as an instrument, the rule of an ideology that preaches scorn for the world and that science is profane. All these traits continue to prevail throughout the entire period that we are considering and, nevertheless, it is a time of awakening, of boom, of progress.

JACQUES LE GOFF,

LE MOYEN AGE

If you want a lover

I’ll do anything you ask me to

And if you want another kind of love

I’ll wear a mask for you

If you want a partner, take my hand, or

If you want to strike me down in anger

Here I stand

I’m your man.

LEONARD COHEN,

‘I’M YOUR MAN’

Contents

PROLOGUE

1 Editorial Meeting

2 Two Brave Boys

3 Iron Man

4 El Peque versus Cholito

5 The Others

6 In the Labyrinth

7 Eyes Wide Open

8 The Investigation

9 Licking the Wounds

10 Clean

11 The Hidden City

12 Light Years

13 Who Doesn’t Know Juan García?

14 Cuyes, Gazelles and Jackals

15 Leaving my Heart

16 Supergirl

17 Full Speed Ahead

18 The Death Train

19 The Journalist’s Violent Calling

Prologue

The building was at least eighty years old. Once it had been the Hotel Arizona, but Alfredo Carranza didn’t know that, nor would he have cared. For him it was the place where he went to see the psychologist the company had arranged for him. He didn’t know that the building at 1000 Calle Talcahuano provided space not only to psychologists and doctors but also to lawyers, small businesses and prostitutes offering a discreet service from rented apartments. For that reason, the number of casual visitors every day was considerable and security on the door was correspondingly lax, despite the presence of two employees in reception.

Carranza knew exactly where he was going. He had taken the number 39 bus from Constitución to a stop on Marcelo T de Alvear, just as he had twice a week for the last three months. As he turned onto Talcahuano he felt a cold wind hit him full in the face. It was one of those autumn evenings when you start to feel winter in the air, pricking your face. Carranza wore brown chinos, a checked shirt beneath a cream-coloured pullover and on top of everything a raincoat which was arguably too light for such a cold day. A storm was brewing. Flashes of lightning lit up the sky and any minute the downpour would be unleashed.

Carranza walked with his hands in his pockets, his head down, his gaze lost among the broken paving stones and dog shit. In the last few weeks he had familiarized himself pretty well with the building. He had noted the indifference with which visitors were greeted and been heartened by it. He couldn’t have coped with anyone catching his eye between the entrance and the therapist’s consulting room.

When had his plan for that day begun to take shape? Perhaps it was on the afternoon when he came out of his appointment with no stomach for the street, people, buses, the journey home, his family and his wife’s quizzical gaze. She was always trying to read in his expression if the therapy was working.

Carranza crossed the street, keeping a tight hold on the paper that he carried in his left pocket. It was a lined sheet of notepaper which he had taken from his eldest son’s folder. He had written on it while locked in the bathroom, before leaving home, in that uneven handwriting that he had never managed to improve, not since primary school. He had folded it four times and stored it carefully in his coat pocket.

Nobody but me is to blame for this.

A few yards before reaching the building, he bumped into someone, a young man who got annoyed and told him to look where he was going. The man looked ready for a fight, but he had to resign himself to continuing on his way, because Carranza apologized without even looking up.

I can’t go on any more. I killed them. All four of them.

Carranza entered the building and, as usual, nobody paid him any attention. The receptionist, short, dark-skinned, with a cheerful face, would later not remember having seen him at all, and – if it hadn’t been for the security camera at the entrance, the only one in the building – it would have been difficult to ascertain exactly when he came in. The people who took the elevator with him wouldn’t remember him either, nor would the lady who, on the fifth floor, was about to get in and asked Carranza if he was going down to the lobby. Nobody saw him enter, or go up in the elevator, or get out on the top floor.

I thought that I could live with this. I thought that I could live with the deaths of the first three. But not with the child’s.

There was nobody on the roof. The lowering sky was lit up by periodic lightning and a few drops of rain began to fall. He walked to the edge of the terrace, which was contained by a low wall, not much higher than his waist. Leaning against the wet concrete, he looked down. He saw the cars waiting at a red light and people hurrying along the sidewalk. Some umbrellas moved from one side of the street to the other, like balls in an electronic game.

I knew that day that I would kill him. That it would fall to me. We all knew it. All the way round I was waiting to come across them. At that moment I wanted to kill them. Both of them. Just for being there, for wanting to ruin my life.

There was no time for anything else. It was all decided. He had thought about it a lot and, although he would have done everything in his power to avoid this, there was no other way out of the hell he was living in, the deep pit into which he had fallen years ago.

But when they appeared I didn’t want to kill them any more. I wanted everything to be different. I wanted to go back to Sandra and the kids. But I killed him, I killed the little one. I want to say that I’m so sorry, say it to everyone, to his family. Sandra, forgive me. Look after Dani and Mati. Forgive me. I just can’t bear it any more.

With difficulty he climbed onto the wall, which the rain had made slippery. He stood up straight, like an Olympic swimmer about to dive. It was simple. All he had to do was step forward and jump. But his legs wouldn’t obey him, he couldn’t bring himself to take the step. The body rebelled against the mind’s plan. Carranza had imagined that something like this might happen, so he reached into the right pocket of his raincoat and took out the pistol he’d brought with him. Then his hand accomplished what his legs had refused to do. He shot himself in the temple and his body fell like a rock, ricocheted off the top floor overhang and finally slammed onto the sidewalk. There were screams of panic, confused movements around the body, the sound of a police siren approaching, another siren, more distant, from an ambulance. And all of it beneath a rain that kept coming harder, crueller and more desolate.

1 Editorial Meeting

I

One good reason to pursue a career in magazine journalism is that you don’t need to get up early. Sure, every now and then you have to cover some event in the morning, and there are also journalists who work for news agencies or websites on the early shift, but the majority start work after 2 p.m. This was not the main reason Verónica Rosenthal embraced the career when she was barely out of her teens, but it had certainly played a part in her choice.

“Whores and journalists get up late,” she would explain sleepily to any friend who called before ten o’clock in the morning.

In fact, it was rare for Verónica to sleep until midday, but it did take her a while to get going. That morning was a case in point. With her eyes half-closed she got into the shower and let the hot water run over her body like the slow caress of a virile lover. She spent less time on the morning shower now that she had cut her hair to shoulder-length – sacrificing the chestnut mane that she used to comb carefully under the water so as not to look like the Lion King’s girlfriend. When she finished she wrapped her short hair rather unnecessarily in a towel and looked for a tampon in the cupboard that contained a mad array of perfumes, talcum powders, hair dyes that she had never used and never would, half-finished deodorants, boxes of panty liners, an electric hair remover that didn’t work and even an ultrasonic nebulizer that her sister Leticia had lent her and which should have been returned a year ago. There was only one tampon left in the box, plus the one she reckoned was in her bag. She’d stop by the pharmacy on the way to work.

Verónica put on mismatched underwear: multicoloured pants she should never have bought, let alone worn, and an aquamarine bra which was at least more comfortable than the ones she usually wore. She didn’t look at herself in the bedroom mirror. Avoiding her reflection was increasingly becoming a habit since she had turned thirty and her body had made its own adjustments to the new decade. She kept promising herself to go to the gym or take up running in Parque Centenario or visit a plastic surgeon, but never got round to any of these, chiefly because she realized that men were much less critical of her than she expected them to be. A pair of tight jeans, a push-up bra or a new bikini easily satisfied them; they didn’t seem to notice all the details that worried her. Perhaps this farce could continue for a few more years.

She urgently needed coffee.

She didn’t feel well, not because she had her period but because she was still a bit hung-over from the night before. Her friends had come over and stayed until the early hours, drinking every last bottle of wine, smoking all the cigarettes and all the available weed. Verónica contemplated with dismay the disastrous scene in the living room. Her friends had shown some solidarity by collecting all the plates, but there were still coffee cups, glasses, overflowing ashtrays, CDs separated from their cases, books taken from the shelves and strewn about. And presumably they thought they had left her apartment tidy because they had washed up a few plates and thrown away what remained of the quickly improvised supper.

Verónica shook her head as though denying the reality of her living room and went to the kitchen to make a coffee.

Two heaped spoons of Bonafide Fluminense went in the Volturno. She waited for the boiled water to reach the top part of the coffee pot, then poured it into the big cup her sister Daniela had given her. She added a dash of skimmed milk but no sugar. As she drank the coffee she began to feel better. All the same, she took a strong aspirin with a glass of tap water. She decided to tidy up the living room before getting dressed.

II

It had rained all night and the bad weather looked set to continue. She didn’t like umbrellas, so Verónica went out into the rain in a black raincoat, a waterproof version of the coat she usually wore on these cold days at the end of autumn. The thought of walking to the number 39 bus stop, then walking three more blocks in the rain at the other end was unappealing. Much better to go to the pharmacy around the corner then take a taxi to the door of Nuestro Tiempo.

She had eaten nothing with the coffee and having an empty stomach made her feel nauseous. She didn’t want to arrive at work in that state, so she asked the taxi driver to take her to Masamadre, a small wholefoods restaurant three blocks from the newsroom. Any other day she would have gone to Cantina Rondinella or got a takeaway from McDonald’s to eat in the kitchen at the magazine, but she felt a pressure to eat healthy food when she had her period.

By the time Verónica arrived at the newsroom it was about two o’clock. Nuestro Tiempo was on the third floor of an office block that had been completed two years ago and still had the new and soulless feel of a place where nobody lives.

The magazine had relocated there soon after the building opened and occupied two whole floors: the third for editorial and the second for administration and the publicity, circulation and IT departments. The journalists sat in clusters distributed along the whole length of the third floor, together with designers, photographers and digital retouchers, each division grouped in small cubicles according to their job.

The first person any visitor to Nuestro Tiempo saw was Adela, the receptionist, a woman close to retirement age, unlike the majority of people who worked at the magazine, who tended to be under forty. Verónica greeted her with a kiss and Adela handed her an envelope: an invitation to an opening at the Museum of Latin American Art. She should find out if any of the girls were going. She’d get bored on her own.

Verónica sat at a long table with the other members of the Society section: her editor Patricia Beltrán, three other writers and an intern. Everyone, apart from Patricia, was already sitting at a computer when she arrived.

“Where’s Patricia?” she asked, putting her coat on a hanger and rearranging her wet hair.

“Don’t you have an umbrella?” Roberto Giménez, one of the section writers, looked at her with the expression of someone puzzling over a hieroglyph.

“Don’t like them. And Fallaci?” she asked again.

“She’s in a meeting with Goicochea and someone else. Remember we’ve got the editorial meeting in twenty minutes?”

No. She hadn’t remembered. She was good at denial: she loathed editorial meetings because they went on for so long and achieved so little. Each writer proposed ideas for an article and discussed or fine-tuned them with Patricia while the others checked their phones, made doodles or stared woefully through the glass wall, as though appealing to a colleague from some other section to come and rescue them. Given that nobody contributed anything to the others’ pitches, Verónica thought that it would make more sense for them to meet alone with the editor rather than collectively lose an hour locked in a room. Worse, since none of them had ever had much time to consider their ideas before the meeting (because some pieces had already been finished the day before, because a new article might now be under way, because the best ideas always strike when least expected, because the best content for a current affairs publication was precisely what was happening at that moment), the majority of pitches were just a formality, ideas that would never come to fruition. Some came up week in, week out (the rise in car ownership, the excessive medication of hyperactive kids, the exotic pets of the rich and famous), but nobody ever wrote them, or even acknowledged that these ideas had been on the table thousands of times before. Patricia would put on a face that said this was either an interesting idea or a shit one (depending on her mood that day), then move on to the next item. At the end, Patricia would dish out articles she had thought of herself or which had been sent down from management (Verónica had the impression that executive meetings were much more productive than editorial ones), or she would end up accepting suggestions at some other point in the working day.

Verónica had twenty minutes before the meeting. Usually five were enough to assemble a list of possible articles that would pass muster with her boss. That day, however, she was clean out of inspiration. Perhaps because she had delivered a big piece the day before on a scam run by the medication mafia operating in public hospitals in Buenos Aires. They were using Plan Remediar (the Ministry of Health system which provided free medication to patients) to record deliveries of drugs that never actually made it to the patient. For example, the doctor would prescribe two boxes of an antibiotic. When the patient went to the hospital pharmacy, they would give him or her only one box, claiming that there were no more left. The patient would leave, and the pharmacist would record two units as having been delivered. It wasn’t that they had stolen the other box. It had never arrived at the pharmacy because the laboratory hadn’t sent it, although it had invoiced for it. Verónica had uncovered the doctors–pharmacists–laboratories nexus without much effort (nobody involved had tried very hard to conceal their part in the crime), and her feature was going to press that night, in the new edition of Nuestro Tiempo.

She opened a blank document and typed: Growing number of vehicles in the city and rest of the country. What can be done about streets and roads collapsing under the sheer weight of cars? And she stared at the computer screen as if this document itself might suggest an article. That was when Giménez spoke up:

“Ha, this guy had the right idea. Listen up,” he said to the others, but none of them looked away from their screens or phones.

Verónica did look up, in fact, but her colleague didn’t notice, because he was reading from the screen.

“A railway employee killed himself by jumping from the roof of a building at 1000 Talcahuano. He fell onto the road and the traffic on Talcahuano was disrupted for more than an hour. Isn’t that brilliant? Instead of throwing himself under a train to screw over his co-workers, the guy decides to piss off the bus and taxi drivers.”

“I bet he killed himself for love,” ventured Verónica, looking back at her barely begun document. “The girlfriend or the lover probably lived in that building or the one opposite and he was trying to get her attention. They’re all like that.”

“All men?” asked Bárbara McDonnell, the journalist who sat opposite her, while typing frenetically.

“Let’s just say all suicidal psychopaths,” Verónica clarified, not wanting to embark on one of those men-versus-women polemics that Bárbara seemed to relish.

“You’re wrong,” said Giménez. “This report says the guy left a letter that said he was sorry for the crimes he had committed. Apparently he was a serial killer or something.”

A murderer-suicide. A criminal with a guilty conscience. It didn’t sound bad. There might not be much for a journalist to get her teeth into, but all the same, the story had potential. Crime wasn’t Verónica’s speciality, but she had always been drawn to lurid stories. She dreamed of writing a feature on a murderous cannibal or an Umbanda priestess who took the blood of virgin girls.

“Where did you read the thing about the railwayman?”

“It’s on the Télam wire.”

Verónica read the news agency story and saw a possible article. Tiempo Nuevo’s crime correspondent had left a month ago for a national newspaper, so crime stories were now distributed haphazardly among the other journalists. She had a hunch that Giménez would want to write about the suicide himself, and thought she’d sound him out.

“How come there are never articles on suicides?”

“To avoid the copycat effect. Apparently when details are published about how someone committed suicide, it sparks a trend and a load of morons go off to do the same thing. Until recently La Nación wouldn’t even print the words ‘he committed suicide’. You had to put ‘he took his own life’.”

“What a bunch of idiots. So, are you thinking of pitching a piece on this guy? The wire story is quite skimpy.”

“No. Deaths are tiring.”

“I might do something, then. Even if only to write ‘he committed suicide’.”

That was Giménez out of the way. She read the story again. What was it in these twenty lines that particularly caught her eye? Perhaps it was the fragment of the letter they had reproduced. It was addressed neither to his family nor to a judge and yet it asked forgiveness for his crimes, specifically for the death of a child. So was the letter a confession, or an explanation?

Patricia Beltrán came out of Management with the newsroom secretary. She went over to where the journalists sat and asked them to go to the meeting room. Verónica quickly typed up a summary of the wire story and printed the page along with her other article suggestion. With any luck, she wouldn’t have to do that piece on the exponential growth of car ownership in Argentina.

III

Verónica came out of the editorial meeting with a headache and took an aspirin from the packet she kept in her desk drawer. Patricia had listened to the pitches and handed out articles. She wanted Verónica to write a piece on the rising popularity of home births.

“My grandmother gave birth to my mother in the middle of a field,” said Patricia. “I thought that humanity had advanced since then, but it seems that some rich girls want to go back to the dark ages.”

Verónica didn’t dislike the idea, although the subject of motherhood was uninteresting to her. It was something that might happen to her one day, in a few centuries. But the thought of giving birth in her bedroom with the help of a midwife horrified her as much as it did her editor.

She had already agreed to hunt down some prospective New Age mothers when Patricia looked at her page of notes and said:

“Hmm, not a single crime story. Anyone got anything?”

Since nobody else replied, Verónica spoke up.

“A railway worker committed suicide last night.”

“We don’t cover suicides unless it’s someone famous.”

“The man left a note saying that he was killing himself because he couldn’t live with the guilt of having committed murders.”

“So he was an unconvicted murderer? Who had he killed?”

“That seems to be the case. Télam hasn’t got much yet, but apparently there was a child among his victims.”

“Right, now you’re talking. If you can find out more this could be a double-page spread.”

“Shall I go with the guilt-ridden suicide, or the stupid expectant mothers?”

“Start with the suicide.”

First she needed to get hold of the letter so that she could examine it. It shouldn’t be difficult to get a copy. Lawyers and judges were generous with journalists, so long as it wasn’t a sensitive case, and even then they were often willing to share evidence, witness statements or whatever. Any time a judge or lawyer put up objections, Verónica brandished her surname: Rosenthal. When she introduced herself this way it was rare for a member of the judiciary not to ask:

“Any connection with Aarón Rosenthal?”

And she, with a carefully calibrated tone of resignation, would admit:

“His youngest daughter.”

Often they had been students of her father, or they had had dealings with the Rosenthal firm in connection with some lawsuit, or there would be some other link of which she was unaware and which she did not wish to know about.

The agency story named Pablo Romanín as the judge in the case. She already knew him from some other trial. He was in his late fifties, sported a fake tan and looked more like a yuppie than a judge. Nevertheless, he seemed to take his work seriously. She looked up Dr Romanín’s mobile number and called him. The irascible tone with which he answered changed entirely when she told him who she was.

“My wife always buys Nuestro Tiempo. How’s the magazine going? You see it everywhere.”

“It’s going pretty well. Doctor, I’m calling you about a case that was heard in your court. The one concerning the railway worker who killed himself by jumping from a building on Calle Talcahuano.”

“Ah yes, a colleague of yours from Télam came to see me this morning.”

“Right, they put out a wire story. I’d love to get a look at the letter.”

“No problem. I’ll ask someone to email it to you. You’ll get it last thing today or first thing tomorrow.”

“Is anything known about the crimes referred to in the letter?”

“We’re just looking into that at the moment. Why don’t you call me tomorrow? I’m sure I’ll have more news then.”

“If you don’t mind, I’d rather come by your office, just to make sure I’m getting the full picture.”

The judge sent his regards to her father before ending the conversation. Until she got hold of the letter and a little more information from the judge, Verónica didn’t have much to do. She stayed on in the newsroom for a couple of hours, sending emails, and later on had a meeting with a journalist from the Politics section, who was considering investigating further links between the Ministry of Health and the medication scam in public hospitals. Verónica didn’t tell him that she had already checked out all the possible ramifications of the case and not found anything. She gave him the telephone numbers and email addresses of the sources which he thought could be useful to him and which she had already dismissed as unhelpful. An experienced journalist would have realized that, if Verónica had found anything worth pursuing, she would be writing a piece about it herself. But the Politics editor – who was also a deputy editor – was too young for his position and very wet behind the ears. What he lacked in pretension, he made up for with arrogance. Verónica couldn’t stand him, for professional reasons as well as personal ones.

It was six o’clock in the evening by the time she had finished with everything. Outside it was dark and the rain was relentless. She called a radio taxi. She wanted to see the building from which the suicidal man had jumped.

IV

Twenty-four hours after Alfredo Carranza had fallen into the void, there was no evidence of the event at 1000 Calle Talcahuano. It was as though the rain had washed away all traces of his death, for the neighbours’ peace of mind. Verónica studied the building’s facade from the opposite sidewalk and thought it particularly grim. A good building to jump from, she thought. The front door was open, which was quite unusual in Buenos Aires.

Verónica crossed the road and entered the old luxury hotel, now converted into offices and apartments for professionals. There were two people in the lobby: an older man who seemed to be monitoring those who came in without intercepting any of them, and a young receptionist who was talking on the phone. Verónica approached the girl and waited until she had stopped speaking.

“Sorry to bother you – have you got a minute?”

She explained that she was a journalist and that she was trying to find out more about the person who had jumped from the roof the previous evening. Like most people in such circumstances, the girl was happy to talk to the press. But unfortunately she didn’t know very much. She said that nobody in the building seemed particularly upset. The girl wanted to talk, to provide some helpful detail. She told Verónica that she hadn’t seen the body – she wasn’t brave enough – but the doorman had. He was the other person working in reception but, apart from a horror-movie description of the body dashed onto the sidewalk, he had nothing useful to contribute. Verónica asked if she could go onto the roof and was told that she couldn’t, that the police had cordoned off the area.

By the time Verónica left the building the rain had stopped. She had learned nothing useful about Carranza. She felt as though she were at the start of something but was moving more by instinct than in response to any particular lead. She didn’t even have a copy of the letter. At this stage, it was better to be patient and wait until the next day, when she would meet Judge Romanín.

Her mouth was dry. She wanted a drink. She was close to Milion, but didn’t relish the thought of running into some of the regulars (including an ex, suitors of various ages and marital statuses and acquaintances whose status varied, depending on what they were drinking and who they hoped to seduce that night). And if she went to one of the nightclubs in El Bajo, like La Cigale or Dadá, she’d be pestered by those creeps who jump on any girl who happens to be alone. She decided to walk down Avenida Córdoba as far as Calle Florida and go to Claridge. At least nobody would bother her there. She liked the bar in Claridge because you always saw little old ladies having tea alongside provincial businessmen pouring alcohol down their throats as a coping mechanism for life in the capital. Anyone at Claridge under the age of forty could be taken for a child. And she was still a long way off forty. She was barely into her thirties and still had the best part of a decade to enjoy feeling like a child at Claridge.

She sat on one of the stools at the empty bar.

“A double Jim Beam with ice.”

An argument in favour of drinking alone was not having to defend her preference for bourbon over Scotch, and especially not having to endure the look of disgust on her friends’ faces when she gave her order. They, meanwhile, would be asking for a Sex on the Beach or a second-rate mojito made with mint, or any other cocktail which they could preface with the word ‘frozen’. The disadvantage was the lack of a friend to chat to while she sipped her drink and gazed at the many different kinds of bottle that lined the shelves against the back of the bar. She called Paula. Her friend answered, then immediately started shouting at someone else.

“Juanfra didn’t want to have a bath,” she explained. “But it’s fine. He’s in the bath now. Think hard before you decide to have children.”

“It’s not in my immediate plans.”

“One can never be sure with you. What news of the Bengali Sailor?”

Verónica stirred the ice cubes in her bourbon with one finger. Her friends had a habit of not naming men in conversation unless the relationship had become formal. So long as they were lovers, occasional boyfriends or guys who they liked but who didn’t give them the time of day, they were given a nickname based on some absurdly exaggerated characteristic. A redhead might be called Fire Lord, a doctor Dr House, a premature ejaculator Mr Speedy and a rock musician Charly García, even if he looked nothing like that Argentine icon. The Bengali Sailor (whose name came from a song by Los Abuelos de la Nada) was in fact quite a successful architect who had a really impressive yacht that he had taken her out on as far as the Uruguayan coast. Every time they had had sex it had been on board the boat, which had led her friends to draw all kinds of conclusions about his needs, limitations, fetishes and fantasies. It was true that her relationship with the Bengali Sailor (who for a short time had been known as Sandokan after Salgari’s fictional pirate but who was better suited to the epithet Paula had given him) had turned into something habitual for Verónica. At one point they had seen each other most weeks. But for a month now he hadn’t called, emailed or texted. She had left a message on his phone and sent him an email. But nothing.

“He’s shipwrecked. He drowned before reaching Carmelo.”

“So, are you upset?”

She stirred the ice cubes in her glass again, then dried her finger on a paper napkin. She would have liked to smoke a cigarette, but it was forbidden in the bar. Verónica hated not being able to smoke in bars.

“I liked the boat, for sure. But if the best he can do is send the odd email or make an occasional phone call, it’s his loss. The guy can’t commit.”

She liked talking to her friends, especially to Paula. It wasn’t the first time she had gone to a bar and called one of them up. Their conversation might be interrupted if the friend in question had to stop to pay a taxi driver or help a child with some task or attend to an inconvenient boss.

They chatted for half an hour. By then the glass was empty. Verónica thought of asking for another Jim Beam but decided to go home instead, to see if the suicide note had come through. She really needed to buy a phone that would allow her to check emails wherever she was.

V

By the time she set off for the Palace of Justice at Tribunales the next morning, Verónica had already read the railwayman’s letter – sent to her in the early hours by an assistant of Judge Romanín – several times. The letter had been typed up and saved as a Word file. She would need to get a look at the original, Verónica thought, to see the man’s handwriting and to study the marks on the paper, see if there were any emphasized words, if his hand had shaken on writing a particular phrase or if his writing had any other particular characteristics.

Basically the letter was a confession. Carranza said that he had killed four people, one of them a child. He asked for forgiveness from his family and from the victims. He seemed to linger most on the death of the child, as though the other deaths were less important, or this death had broken something. A pact with accomplices? Were the other deaths in some sense natural, and the child’s a murder that defied logic? What kind of logic, then?

She reached the Tribunales law courts early. It was an area of Buenos Aires she knew well: she had gone to high school at Instituto Libre de Segunda Enseñanza, almost opposite the Palace of Justice, and her father’s law practice had been on Tucumán since before she was born; it was a solemn-looking office which she had sometimes visited with her mother and sisters before or after going to the cinema. She knew every bar in the area, every bus stop, every bookshop, every stall in the book market in the Plaza Lavalle, every tree in that square. She would never have claimed she was brought up in Tribunales, but she had certainly spent many of the days of her childhood and adolescence in and around its buildings.

By contrast, the Palace of Justice was still a mystery to her, even though she had often needed to go there in search of information. In the past it had been the place where her father waged epic battles, like a prince in his enemy’s castle. At least that was how she had imagined it, especially when her father disappeared for weeks, physically or mentally. At those times, even when he was at home, he was like a kind of ghost who spoke on the phone or received guests in the library. Every now and then he would return to normal life, smiling and triumphant. She couldn’t remember ever seeing him defeated. All the city’s lawyers converged in that building full of stairs and doors leading nowhere, an example of a kind of demented architecture rarely seen in Buenos Aires. Now she too was climbing the marble stairs towards the office of Judge Romanín, and every corridor filled with lawyers and clients revived that sense of mystery she had felt as a child about the castle in which she sometimes lost her father.

After various twists and turns she arrived at Romanín’s criminal courtroom. The judge had not yet arrived, but five minutes later he appeared. He apologized for the delay, gave some instructions to his staff and asked for two coffees. He ushered her into his office. For all the efforts he made to stay young, Romanín was an older man now, not far off retirement. Verónica didn’t know exactly how he was connected to her father, but from the way he spoke, she gathered that there was some affection between them. He even knew that her mother had died five years ago.

“Did you receive a copy of the dead man’s letter?”

“Yes, thank you, Doctor, I got it this morning.”

“The man clearly wanted to commit suicide. He shot himself in the temple, then fell from the roof.”

“There’s no possibility he was coerced into going to the building’s edge and shot there?”

“No. The expert evidence all points to him holding the gun in his right hand. There were also traces of gunshot residue. There’s nothing to suggest he had any enemies.”

“In the letter he talks about four murders. Is anything known about those?”

The judge sprawled in his chair and smiled at her.

“If you’re asking because you believe the deceased was murdered, I’m afraid I have to disappoint you.”

He searched among the files on his desk, taking off his glasses to see better close-up. He read something in an incomprehensible whisper, put the folder down, put his glasses back on and continued:

“The poor man hadn’t killed anyone. Bah, sensu stricto he had, but no judge would ever have convicted him, even though he was under arrest for a few hours. Carranza was a train driver on the Sarmiento railway. And he ran over four people. On different occasions, over a period of three years.”

“You mean the four deaths he refers to in his letter were the result of train accidents?”

“Suicides, misadventure. Accidents – yes. I have the worksheets here provided by Trenes de Buenos Aires, the concession holder, where the four fatal incidents are recorded.”

“Is one a child?”

“Exactly. Yes, a nomen nescio, a John Doe. It was never possible to identify the body, and nobody came forward to claim it.”

They both fell silent. Verónica tried to fit this new information into the scenario she had been mentally building.

“So Carranza killed himself because he ran over four people in separate accidents.”

“Apparently the engine drivers get quite traumatized. In fact, here’s an interesting detail for you: that man fell from the building where he used to see his psychologist. He had been sent for therapy by the company. We spoke to the psychotherapist and, even allowing for patient confidentiality, he told us everything we needed to know: Carranza had been shaken by the accidents, and perhaps that sparked a suicidal tendency that was already there.”

“I can see it must be a terrifying experience to run someone over with a train, but would that actually lead you to take your own life?”

“Look, Verónica, we judge the facts. And very often the intentions. But, to be frank with you, we know very little about the real reasons that lead people to become criminals, to kill or to commit suicide. That’s the job of psychologists and people like you – journalists.”

“Journalists,” Verónica repeated. “Once upon a time, poets were the ones who knew most about the heart’s secrets. Things have come to a pretty pass if we’re relying on psychologists and journalists now.”

She asked if she could see the original letter. The judge found it in his folder and passed it to her. A shiver ran down her spine. On this page, torn from an exercise book, in this uneven handwriting, the dead man ceased to be an abstract entity and became a real person. Death was in these written words much more than it was in a corpse.

She handed him back the letter and had stood up to say goodbye when a doubt occurred to her.

“Just one other thing: has all this information been corroborated by the family?”

“We’ve spoken to his wife. In cases like this the family is very stricken. She told us that she had imagined something like this could happen and that she couldn’t forgive herself for not having done more to prevent it. You see, guilt is like an oil stain transferred from one body to the next: someone jumps in front of a train – for whatever reason – triggering guilt in the driver that in turn leads him to suicide, which then makes a loved one feel guilty for not taking enough precautions. And I’m sure that she did take them, that the driver did what he could with the train, that the first suicide should have given life another chance. What can one say?…I don’t want to get maudlin.”

If anyone had asked Verónica which streets she walked down in the half hour following her interview with Romanín, she would have struggled to reconstruct the route. Her mind was completely focussed on the new information the judge had given her. Somehow, though, she had ended up in a bar on Avenida de Mayo, where she was now reading the suicide note yet again. There were so many loose ends in the confession that it was impossible to be satisfied with Romanín’s explanation. Judges – as she had once said during an argument with her father (a few years ago now, when they still argued about such things) – don’t want to deliver justice but to close cases. If the clues and evidence pointed to the guilt or innocence of the accused, they acted accordingly. They never dwelt on or worried about the deeper causes, about the motives that underlay what was self-evident. That was why, as Verónica told her father, she preferred being a journalist: she crossed the line at which the judges stopped. The conscience of a magistrate – she had declared passionately, mindful of her father’s growing anger – is happy with the most superficial forms of justice.

And Romanín struck Verónica as one of those judges who are happy with little. A guy shoots himself and jumps from a rooftop. Suicide. Case closed. Bring out the next one.

Carranza had committed suicide, no doubt about that. He had killed four people while driving his train. He was getting therapy for the trauma those accidents had caused him. Going on what the letter said, he had been able to deal with the first three deaths, those of the adults, but not the last, the child’s. And that was the point where the letter started to reveal more than what was written.

I knew that day that I would kill him. How could Carranza have known that he was going to run the child down? Or was this simply a way of expressing himself? A kind of premonition?

That it would fall to me. To him and not to someone else? Would it fall to him by chance, or for some reason? What was that reason, if there was one?

We all knew it. The change from singular to plural struck Verónica as the clearest sign that this was more than a simple suicide. And that plural implied various people. Who? If they all knew, it was not a premonition but a foregone conclusion. And if they had known that this would happen, why had they not tried to prevent it?

All the way round I was waiting to come across them. Another troubling plural. He had run over a child who was not alone. How had the other one escaped injury? Or had someone pushed the child under the train? If so, then there was a criminal involved who was not the driver. Did Carranza know him? Had there been some sort of arrangement between them?

At that moment I wanted to kill them. Both of them. Just for being there, for wanting to ruin my life. But when they appeared I didn’t want to kill them any more. That abrupt change in mood reminded Verónica of something that had happened recently: she had never run over anyone, but a little while ago a motorcyclist had crossed in front of the car her sister Leticia had lent her. Her first reaction had been terror at the thought of crashing into someone but afterwards, after frantically applying the brakes to avoid an accident, she had felt a dreadful desire to run over that idiot in the helmet, who was still progressing down Avenida Córdoba without a care in the world. Perhaps that was what had happened to Carranza. He felt like killing because he had experienced the terror of being in a position to kill.

There were too many doubts to resolve alone. She called her editor. She would see her at the magazine anyway, but this was something that couldn’t wait until the afternoon. Besides, she knew that Patricia didn’t mind being called at any time if it was about work.

“I’m literally as lost as the characters in Lost,” she replied when Patricia asked her how the investigation was going.

“So – have crimes been committed here, or not?”

“Judge Romanín says not. Carranza ran over four people in separate accidents. Three men and a boy.”

“I figured as much yesterday when you suggested the piece.”

It annoyed her that her editor should be a step ahead of the rest of them, the journalistic pack.

“Why didn’t you say anything, then?”

“Because figuring something isn’t the same as knowing it. A basic principle, not much taught in journalism schools.”

“Something in that letter doesn’t add up – lots of things don’t. There’s something fishy about it, Pato. I don’t know what, but there’s definitely something going on.”

“So I won’t cross off the piece for this week?”

“Cross it off for this week, definitely, but I’m going to keep investigating. I need to find a way in.”

“Have you worked out what to do next?”

“I need to find out more about the people who died. And speak to someone from Trenes de Buenos Aires.”

“Over what period of time did he run over the four people?”

“Three years.”

“If I ran over someone in my car I’d never drive again.”

“A person has to work.”

“An employee kills four people in three years and the company lets him keep working in that capacity? It’d be good to find out if there are other train drivers in the same situation. How many deaths are there a year? What’s the protocol when a driver runs over someone?”

“I don’t think that’s the kind of information the PR person at TBA is going to give me.”

“You mean the spokesperson. That kind of company has a spokesperson, just like ministries.”

“Is a spokesperson any more likely to be helpful?”

“No. But first you should try to resolve the doubts you have about the letter. Start with the driver’s family. Try to speak to someone close to him, and perhaps they’ll suggest a way into the company.”

Patricia always knew which way a journalist should go. Where others were myopic – or completely blind – she saw clearly. It was a quality that inspired both admiration and irritation in Verónica, because she couldn’t help feeling that she would have reached the same conclusion five minutes later. But Pato always got there first. Like a good chess player, she thought one or several moves ahead.

Verónica called Judge Romanín on his mobile phone, apologizing for bothering him again.

“Do you happen to know where Carranza’s wake is?”

“It’s already finished. He must be on his way to the cemetery in Avellaneda by now. They were going to bury him at midday.”

She paid for the coffee, went outside and hailed a taxi. With any luck she could get to the funeral before the mourners dispersed.

VI

Unfortunately, she didn’t know where in Avellaneda the cemetery was. Her knowledge of that area was limited to the home grounds of Independiente and Racing, the train station, the street leading to the soccer grounds, Calle Alsina and Avenida Mitre. It seemed like a bad idea to arrive at the cemetery in a taxi from the capital: it would attract too much attention. So she asked the taxi driver to take her as far as 500 Avenida Mitre (wherever that was – she hoped it existed).

On the way she called her sister Daniela. They had arranged to have lunch together, but it was going to be impossible to get there on time. She felt a little guilty cancelling it, because she very often had to call off arrangements with her sisters. It was bad luck that something came up every time they were due to meet. They thought she was making excuses. Verónica didn’t want to believe that this was symptomatic of some phobia brought on by family life.

Soon after they had crossed the Pueyrredón bridge and were on Avenida Belgrano, Verónica spotted a minicab company and asked the taxi driver to drop her there. It would be better to continue the journey in a local cab.

This second driver took her right to the information office, inside the cemetery itself. There she found out that Carranza’s interment must already be under way, a few hundred yards away. She asked the driver to wait for her and set off alone to find the plot where she had been told the mourners would be. The previous days’ rain had left puddles on the path and there was a smell of damp earth. If she disregarded the tombs around her, she felt as though she were walking through a muddy field.

In the distance she saw a sizeable group of people standing in the place to which she had been directed. She walked towards them without hurrying. There must have been about thirty people, perhaps more. She had never been good at calculating the number of people present at any event. Verónica stood at the back of the group, hoping to seem like a member of the funeral party, not a busybody. Her arrival had coincided with the moment the coffin was lowered into the grave. The mourners pressed forward to throw handfuls of earth onto the coffin. The sound of loud sobbing helped her to pick out the people who must be Carranza’s wife and children: the three of them clinging together as a single body, as though wrapped in a magnetic cape that prevented anyone else from joining the embrace or consoling them. There was also a woman who walked up to the grave, threw in a handful of dirt and stood staring into it as though waiting for something to happen, for reality to change and for the dead man to emerge from the grave. Someone approached the woman, gently took her by the shoulders and led her away. To one side of the grave was a group of unaccompanied men: they must be Carranza’s fellow workers. She counted them, to be sure of the number: nine. They looked serious, neither crying nor consoling each other. Verónica wished that she had been present when the cortège arrived, to see which of his colleagues had carried the coffin from the hearse to the grave. She tried to make out gestures, anything to help her deduce which of the men was a greater friend of Carranza’s than the others. But there was nothing. They were a block, distinct from the rest of the mourners, a separate group within the funeral party. For a moment it seemed to her that one of them stood out from the rest. She kept watching him, but she didn’t see anything more to back up her hunch.

The burial ceremony was over. The people returned to their cars. The co-workers made for the exit. Verónica was thinking of going up to talk to them when she heard an older man say to the elderly lady who was with him:

“Did you give your condolences to the sister?”

“To whom?” asked the woman, louder. She must be a little deaf.

“To Carina, Alfredo’s sister.”

The old couple walked towards the woman who had stood longer than usual beside the grave. Verónica followed them.

Both of them greeted the woman, who must have been about forty-five. She thanked them, looking dazed, and the couple moved to one side. Verónica walked up to the woman then and gave her a kiss, as though she too had been a friend of the dead man. The woman must have been greeted in similar fashion by many people she didn’t know that day.

“Carina, forgive me for bothering you at such an awful time.”

“Were you a friend of Alfredo?”

“No, I’m a journalist. I don’t want to intrude, but I wondered if I could talk to you about your brother at some point.”

The woman gave her a sullen look. A man started walking towards them.

“My brother committed suicide. There’s nothing else to say.”

The man took Carina gently by the arm and told her that he would walk her to the car, which was parked about fifty yards away. Carina let herself be led. Verónica kept pace with them both.

“Your brother suffered a great deal. And the company he worked for did nothing for him.”

“They paid for a psychiatrist or something,” said Carina, without looking at her.

“I believe that the company is responsible for what happened to your brother.” She took the woman’s hand and placed her business card in it. “Here’s my number. Please call me.”

Carina nodded briefly, either in agreement or as a way of asking her to go away, which Verónica did immediately. She doubted that Carina would call, but if she did not do so in the next few days, she would think of another way to find her.

VII

The weekend was uneventful. On Friday night she went to Bar Martataka, knowing that some of her friends would be there. By the time she arrived, Alma, Marian, The Other Verónica and Pili, sometimes known as Spanish Pili, were already there. Absent were Paula – who had to look after her son – and some girls who were variously on holiday, in relationships or sitting at home depressed, eating chocolate and binge-watching box sets.

She was in need of her friends and their debauchery, of their light-hearted, boastful and mercilessly cynical conversation about the rest of humanity, especially the men who passed through their lives or paraded themselves in the bar that night. A few tables away was a group of men she knew. In fact, in terms of age and profession, this coterie was quite similar to theirs. It included the odd journalist, a writer supporting himself with workshops, a psychologist and a philosophy teacher. What with various comings and goings, and trips outside to smoke, by around 11 p.m. half the girls’ group had moved over to the boys’ table, and vice versa. Verónica had ended up on the same table as the writer who lived off his workshops. He was telling her she ought to write fiction.

“Whenever I read your pieces I notice how well written they are. You’ve got such a good style – I think you should write novels or short stories. Don’t you agree?”