8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

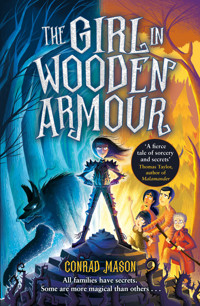

- Herausgeber: David Fickling Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Brokewood Valley is a strange and mysterious place. There are old magics under the earth, and dark forces at play. So when Hattie and her brother, Jonathan, arrive to find their Granny missing, they suspect something sinister is going on.Hattie uncovers these unusual powers in the land and is determined to find out the truth. Where is Granny? How is this connected to her mum's death, seven years go? And who exactly is the girl in wooden armour?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 279

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

For Ida and Arthur, with love

Contents

PART ONE

THE CURIOUS HISTORY OF BROKEWOOD-ON-TANDLE

Chapter 1

BRADLEY COOPER HAS A BAD FEELING

‘Nothing’s going to happen, Bradley,’ said old Deirdre Gavell to her stuffed squirrel. ‘Don’t be such a worrywart.’

Bradley Cooper didn’t say a word. The clock had already struck seven, but tonight she had the funniest feeling – as though he didn’t want her to go.

Which was nonsense. He was just a stuffed squirrel, after all.

‘Youngsters,’ she tutted. ‘Always making a fuss. Well, if it will make you feel better.’ She stroked his furry head, then took three twigs from the mantelpiece and slipped them into the pocket of her patchwork coat. She had gathered them a few weeks before, digging in the leaf litter beneath the branches of an ancient beech tree.

Something rustled outside. Her heart lurched, and her fingers tightened around the twigs. But it was only a bird taking flight from the shadowy bushes outside the living room.

Deirdre screwed up her wrinkled face and stuck her 4tongue out at the mirror. That made her feel better. Nothing bad ever happened in Brokewood-on-Tandle. Not any more.

She shuffled into the hallway, buttoning her coat. A bowl of peppermint humbugs sat on the dresser, and she unwrapped one and popped it in her mouth. The journey was a mile. She couldn’t walk as fast as she used to, but the moon was shining and the rain wasn’t due for a few hours yet.

Silence greeted her as she unbolted the front door and stepped out into the night. Not so much as a gust of wind to sway the branches of the weeping willows. Even the River Tandle seemed still, as though the world was frozen, waiting for something to happen.

Hairs prickled at the back of her neck. Silly old woman. Getting jumpy because of a squirrel.

And yet …

These last few weeks, nothing had felt quite right. The beech leaves had been whispering strangely in Hook Wood. Yesterday, a dead branch had snapped beneath her boot so loudly it had startled her. And when she laid a hand on the trunk of the alder that grew alone by the brook, she had felt a coldness that lingered even after she had removed her fingers.

It was almost as though the trees were trying to tell her something.

Hunching her shoulders, she hurried across the 5drive. Tonight, at the meeting, she would talk to her friends. They would tell her that she was going loopy – a mad old woman who spent too much time alone with Bradley and the trees. How long had it been since she had last seen her grandchildren? A year, at least. Nearly two. Hattie and Jonathan didn’t know the truth about their granny – poor, dotty Deirdre – and they probably never would.

She sucked hard on her humbug and forced the thought from her mind. She might be old, but there was no need to be sentimental.

Her Doc Martens crunched the gravel with every step. Nowhere to run, out here in the open. She didn’t know why the thought had occurred to her. Ridiculous. Anyway, her running days were long behind her. She stared straight ahead, resisting an urge to peer into the shadows.

As she strode over the humpback bridge, her breathing began to slow. And she was exactly halfway across when someone came stumbling from the bushes up ahead.

It was a slim figure, hooded and dressed in dark, baggy clothes. A girl. She looked older than Deirdre’s granddaughter Hattie. One of the teenagers from the high school in Tatton, at a guess. They often came to the woods to smoke cigarettes and drink cider in secret. This one must have got lost and separated from her 6friends. It was easy enough in the woods around the Tandle.

Deirdre spat the humbug into her handkerchief and tucked it away for later. She couldn’t help feeling relieved to see another person. ‘Hello, dear,’ she said, smiling. ‘Can I help you?’

The girl didn’t reply. She was reeling, unsteady on her feet. She staggered into the road and sank to her knees. Deirdre glimpsed a flash of pale skin at the bottom of the torn, filthy jeans. And with a jolt of alarm, she realized that the girl wasn’t wearing any shoes.

She sped up, hurrying across the bridge. Alcohol poisoning, surely? With luck the girl would have a phone to call an ambulance.

‘Hello?’ she called. ‘Can you hear me?’

The girl curled slowly into a tight ball, her whole body shuddering.

Deirdre shrugged off her coat and went to drape it over the girl’s shoulders. Up close, the poor creature stank. A damp, fishy smell as though she had been swimming in the river.

Her fingers brushed against the worn fabric of the girl’s hoodie, and at once a strange sensation stole over her. She felt as though she were in another place entirely. As though she were falling backwards down a well, plunging deeper and deeper. Watching the sky getting further out of reach.

7A chill swept across her skin.

She snatched her coat and backed away. Fumbling in its pocket, she found the twigs. Her hand closed tight over them. They were all she’d brought to protect herself – not even a daisy chain, a lump of silver or a handful of salt. Old fool. What had she been thinking? She cast around, looking for a clump of snowdrops or a puddle of still, stagnant water. Nothing.

The girl had begun to make a sound – a guttural, barking noise. She wasn’t choking, wasn’t having a fit, wasn’t even cold.

She was shaking with laughter.

Deirdre tugged her hand free from the coat. She channelled her fear, pouring it down the length of her arm, through her fingers and into the wood. The twigs responded, twitching and winding together like vines. Come on. Faster …

In the darkness they were changing, becoming something new. A spiralling blade, slender and sharp and bristling with magic. Deirdre brandished the wooden dagger in front of her, raising her coat like a shield in her other hand. ‘I don’t want to hurt you,’ she said. But her voice was a whisper.

The girl straightened, her hood slipping back from her head. And now it was plain to see that it wasn’t a girl at all.

Its hand lashed out, smacked Deirdre’s aside, sent the 8wooden blade flying into the shadows. Deirdre gasped in pain at the thin scratches that scored the inside of her wrist. Its fingers were tipped with curving black claws.

The thing in the shape of a girl stepped forward, not stumbling at all this time. Limbs unfolded from its back, creaking, protruding through rips in the fabric of the hoodie. Delicate, bat-like bones fanned out like spreading fingers, with sickly white skin stretched between them. A pair of wings.

‘Get away from me,’ Deirdre croaked.

The girl-thing said nothing. Strands of lank black hair hung in clumps around a face that was little more than a skull, with gaping black nostrils in place of a nose. Its dark eyes gleamed wetly, too large and too round to be human. Its thin lips split apart to reveal a hundred splintered teeth, like jagged rocks in a dank cavern. It was grinning.

Then, with an unearthly shriek, it flew forward.

The cold black claws closed around Deirdre’s shoulders as the monster bore her back towards the river. She kicked out desperately, but her feet had already left the mud.

Together they smacked into the surface of the Tandle, and Deirdre gasped at the freezing shock of the water. Her coat swam up around her. She thrashed wildly, but her attacker was too strong by far. It was on top of her, pushing her down.

9That awful face, looming, grinning, staring …

Then searing pain as the claws dug in deep, plunged her down again.

The black water swallowed them both. Bubbled furiously for a few moments before it stilled.

Silence. Only the wind rustling the trees.

Until at last, it began to rain.

Chapter 2

RUM AND RAISIN

The rain fell harder as they left the motorway. Down it came, drumming on the roof of Benjamin Amiri-Gavell’s sleek silver car and streaming across the windows. Hattie Amiri-Gavell shivered and stared out from the back seat, lulled by the soft squeak of the windscreen wipers as the car wound its way up the hillside.

A rolling carpet of grass and rocks and sheep fell away beneath them, disappearing into the distance in a damp grey haze. Hattie leaned past the passenger seat to check Dad’s phone – thirty-two minutes to go.

‘You’re not listening!’

She blinked and turned to her brother. Jonathan was bundled up in a large coat, but underneath it he wore his faded black Crown of Elthrath T-shirt, just as he always did. His black curls exploded from under a frayed woollen monkey hat, the monkey’s arms dangling past his ears. Made by Mum, Hattie remembered. According to Dad it had taken her a year, and it was the first – and last – thing she had ever knitted.

11‘Was so.’

‘Were not. What did I say then?’

‘Something about damage points. You said swamp elves have more than you’d think. Or less.’

Jonathan rolled his eyes. ‘That was ten minutes ago! I don’t talk about Crown of Elthrath the whole time.’

‘Only when you’re awake,’ said Hattie.

Jonathan punched her on the arm, but he was only seven so it didn’t hurt. Besides, Hattie could tell he didn’t really mean it. ‘I said, how many sheep do you think a dragon could swallow before it got full?’

Hattie looked at the bedraggled sheep dotted about beyond the drystone walls and tried to care. ‘I don’t know. Three?’

‘Three?’ snorted Jonathan, as though it was the most ridiculous thing he’d ever heard. ‘A fully grown dragon? Are you serious?’

Hattie sighed. ‘We’ll ask Granny when we arrive.’

‘Granny’s weird,’ said Jonathan.

‘Exactly.’

Old Deirdre Gavell was weird, thought Hattie, as she went back to staring out of the window, and as the car swerved on round the curves of the steep, bumpy country road. With her tatty patchwork coat, and her big clumpy Doc Martens, and her stuffed squirrel that she talked to as though it was really real.

Once, when Hattie was eleven, Deirdre had come to 12stay at their little flat in London. Dad had planned a trip to the Science Museum. But instead Granny spent the afternoon making friends with a mangy fox that was going through the bins, then following it through the local alleyways. After that she had taken Hattie and Jonathan out in the rain to pick nettles by the canal, and made nettle soup for dinner instead of the spaghetti Bolognese that Dad had planned.

When Granny woke the whole family up at 1 a.m. to go swimming in Hampstead Ponds, it was the final straw. Dad had flipped out, and Hattie and Jonathan came down to breakfast the next morning to find that she had already gone.

Jonathan was disappointed, until Dad distracted him with some maple syrup to put on his pancakes. Hattie had felt the same way. They’d got soaking wet in the rain, and the nettle soup had been disgusting, and it was exhausting not knowing what crazy thing Granny was going to do next. But even so, there had been something … exciting about it all. Dad always told them to be sensible. And Granny hadn’t been remotely sensible. Not for a second.

Since that visit, they’d hardly seen Granny at all. Only on neutral ground, for an hour or two, under close supervision from Dad. Once for a picnic in the New Forest. She had never come back to London, and Dad never took them to stay with her.

13Until now.

Hattie felt for the letter, neatly folded in her pocket. It had arrived just a few days ago. It was brisk and straightforward, and she knew it word for word.

PLEASE COME AND VISIT ME. GRANNY

Hattie frowned at her reflection in the window. There was something funny about the letter – something she couldn’t quite put her finger on. Yes, it was barely two lines long. And yes, it was hand-written in large, messy capital letters with bright green ink. But that wasn’t it. A normal person would have called, but Granny ‘didn’t believe’ in phones. Maybe it was the way she had said ‘please’. She never normally said please. She never normally asked for anything at all.

‘You’re doing that face again,’ said Jonathan, wrenching her out of her thoughts. ‘Like you’ve swallowed a gobslopper.’

‘I definitely haven’t,’ said Hattie, before Jonathan could explain what a gobslopper was. Something to do with trolls, probably. Trolls were Jonathan’s second favourite thing to talk about, after Crown of Elthrath. ‘I was just cogitating. This is my cogitation face.’

Jonathan wrinkled his nose. ‘What’s that mean?’

‘It’s the ugly bit on the front of your head.’

14She fended off another punch.

Another gust of rain shuddered on the windscreen, and the car swayed with the wind. ‘Blimey, this weather!’ muttered Dad, from the driving seat. ‘Hey, how about some of that fudge, Hatster?’

‘I can’t believe you made rum and raisin flavour,’ Jonathan complained, not for the first time.

Hattie laid a protective hand on the foil-wrapped baking tray that sat on the seat between them. ‘Not till we arrive.’

‘You sound just like your mother,’ said Dad.

Everyone went quiet after that. Dad didn’t often mention Mum, but whenever he did he seemed to take himself by surprise, and then disappear into his own head for a while.

They drove on in silence.

‘There it is!’ said Jonathan suddenly, leaning forward and pointing through the rain-washed windscreen. Hattie couldn’t resist leaning in next to him.

They had reached the top of the hill, and below them a little group of cottages huddled in a softly sloping wooded valley, like eggs in a nest. The village was blurred by a mist of rain, but Hattie could see that the roofs were all steep-sided and wonky, tiled with grey slate, as though the buildings had sprouted naturally out of the landscape.

A sign glowed, briefly fluorescent in the car 15headlights as they whipped past it. Welcome to Brokewood-on-Tandle.

They could see the Tandle itself now, rushing white and swollen by the rain as it snaked down the far hillside, disappearing into the woodland that swaddled the village as it ran to lower ground.

Hattie got a shiver of excitement as she drank it all in. The last time they’d visited Brokewood was a million years ago, for the funeral, when Jonathan was just a baby. And they’d never been to Granny’s home before. Not once.

She glanced at Dad, tapping his fingers on the steering wheel and humming distractedly to himself. He was as clean-shaven as ever, hair neatly moussed and parted, white shirt and soft grey cardigan ironed and spotless. He still looked uneasy, though. Hattie could hardly believe he’d agreed to this trip, even with all the begging and whining and pleading from Jonathan.

Dusk had fallen as they wound down a narrow lane at the edge of the village, then turned onto a rocky track. The car bumped and bounced, splished and splashed through puddles of rainwater. They crossed a humpback bridge, and Hattie saw the Tandle again, glimmering like treacle below her window.

‘Are we nearly there?’ asked Jonathan.

Then a wide wooden gateway loomed up ahead with the mill hand-painted on one of the posts. And there it 16was, beyond the open gate. Granny’s home. And Mum’s, thought Hattie. When she was a little girl.

The tyres crunched on gravel, and the headlamps lit up a great wooden waterwheel, the paddles bumpy with moss. The mill itself was big and square and built out of grey stone. It stood alone, with no company but a clump of willows that grew on the riverbank. Their branches swayed in the wind like witches’ fingers.

The car rolled to a halt. The engine was still running, the windscreen wipers still gently swishing. ‘You go ahead, team,’ said Dad. ‘Just got to make a quick phone call. Don’t scoff all the fudge, OK?’

Hattie and Jonathan climbed out.

‘That’s weird,’ said Jonathan, as they pulled their hoods up against the rain.

‘What is?’

‘Granny left the door open.’ He pointed. Sure enough, the big oak door was swinging softly on its hinges, and light spilled from inside.

‘She must have popped out for milk,’ said Hattie doubtfully. The wind blew, and the door banged against the wall.

A short dash to the doorway, then they were shrugging their coats off.

The noises of the wind and the rain fell away as they stepped inside. The hall was warm and cosy and untidy, with rough stone walls and red-and-black checkerboard 17flagstones. The dresser was cluttered with unopened letters, and a bowl of stripy sweets was balanced on the spine of an open book – an encyclopaedia of insects. Hattie couldn’t imagine a place more different from their own small, white modern flat back in London.

‘Granny?’ she called.

Silence. For some reason, it made the hairs prickle at the back of her neck.

‘Maybe she found a fox to follow,’ said Jonathan.

Creeeak.

The sound froze them. A floorboard shifting, somewhere overhead. A footstep?

‘What was that?’ Jonathan’s eyes were big and wide.

‘Granny?’ Hattie tried, a second time.

No reply. Again.

The stairs that led up from the end of the hall were old and stone and disappeared into darkness.

Hattie turned to Jonathan and laid a finger on her lips. ‘Wait here,’ she whispered.

Then she climbed the steps, as quietly as she could.

Chapter 3

A TRICK OF THE MOONLIGHT

At the top of the stairs, Hattie paused and listened.

The moon shone through a window at the end of a short corridor, silvering the ancient floorboards. A couple of wooden doors – bedrooms or bathrooms – both closed. No one to be seen. Nothing to be heard.

She relaxed. Old houses made all kinds of funny noises, didn’t they? It was probably just a mouse that they’d heard, scuttling behind the skirting boards.

Then she noticed something. Near the window, where the wall met the floor, there was a line of soft yellow light. About the width of a doorway.

Hattie crossed the landing on tiptoes. When she reached the sliver of light she knelt and ran her hands over the rough wall above. There, running between the stones, she felt something under her fingertips. An edge. She frowned. Gave a gentle push.

And with a squeak of old hinges, a section of the wall swung inward.

19‘Hattie?’ called Jonathan, from downstairs.

A secret door.

She knew that she shouldn’t go in. She knew that Dad would tell her not to. But what if Granny was in there? It would be silly not to check, wouldn’t it?

And besides. A secret room.

Holding her breath, she pushed the door all the way open and stepped inside.

The room was small and round, with a high ceiling. Shadowy bookshelves towered over her on every side. There was a polished walnut desk and a shabby leather armchair, and the dim yellow light came from a table lamp that sat on the desk. Above it hung a large framed OS map of the Tandle Valley.

There was a musty, floral smell in the air. Hattie’s foot brushed at a string of withered flowers. A broken daisy chain, lying tangled on the floor.

Granny wasn’t there. No one was.

The shelves held objects, as well as books. A chipped old wine glass, covered with cling film and half full of a blue liquid that appeared to be frothing and bubbling. A stack of sharpened bones (human bones?) held together with a rubber band. There was a dusty Mason jar full of tiny glittering things that might have been beetles. A papery pair of gloves dangled from a shelf, woven out of yellowed grass. Dried-out chunks of bark, lined up in rows according to some peculiar logic that Hattie couldn’t fathom.

20She reached out to touch a helmet made from twigs, like something an ancient warrior might have worn. Her heart was thumping. This is fine, she told herself. This is normal. Probably loads of people have secret rooms full of weird old books and jars of beetles and bits of wooden armour. It was probably an adult thing, like coffee and having a lie-in.

Except that it definitely wasn’t.

Hattie knew that Granny was odd – in a safe, harmless way. But this room felt different. It was seriously odd. A deeper, stranger kind of oddness altogether.

In fact, it gave her the creeps.

She moved to the desk. There was a mug full of pens. More stacks of leather-bound books. And a framed photo of a family dressed in swimming costumes on a pebbled beach.

Her family.

She hesitated. Steeled herself. Then she picked it up.

In the photo it was a cold, grey day. Their skin was goose-pimpled, their cheeks and noses were red, but everyone was grinning. Dad, a towel wrapped round his waist, bending down to tickle Hattie. Hattie herself, squirming and giggling, her curly black hair soaked from a dip in the sea and plastered against her head.

And there, sitting cross-legged, holding baby Jonathan in her arms …

The image of Mum took her breath away, like it 21always did. She felt suddenly hollow. As though she was the ghost.

Molly Amiri-Gavell was tall, slim and pale, far paler than the rest of the family. The wind whipped her long chestnut hair across her fine-featured face. Even in her swimming costume, she still wore her beloved silver bangles on her wrists, and her favourite pendant dangled on a black cord from her neck – a slender white key, crafted from silver birch. Probably a present from Granny, Hattie thought. Her brown eyes looked bright and alert, and her smile was as mysterious as ever: the smallest curve of the lips, as though she had a secret she would never tell you.

Hattie gazed at her mother, letting the rest of the world fall away. She imagined that she could step through the frame and into the photograph. That Mum would throw her arms around her and hold her tight, like she did when Hattie was little. That everything would be normal again. Like it was before.

‘What is this place?’

Hattie almost dropped the photograph. Turning, she saw Jonathan at the door. ‘Don’t touch anything,’ she said, laying the photo face down on the desk.

Jonathan picked up a long golden thing that looked a bit like a pen. He gave it an experimental tap on a book-shelf. ‘It looks like a witch’s den,’ he said. And Hattie couldn’t help thinking that the gold thing did look remarkably like a magical wand.

22She switched off the table lamp. ‘Come on,’ she said. ‘There’s no one here.’

Jonathan bounded out and down the stairs, singing to himself.

Taking one last look around the darkened room, Hattie followed. But halfway across the landing she stopped again. On one of the doors there was a little wooden sign, hanging from a nail and painted in primary colours. Molly’s Room, it said, in cheerfully mismatched letters.

Her throat tightened as she laid a hand on the cool brass doorknob.

The top of the sign was thick with dust. It must have hung there for years and years – ever since Mum was a kid, growing up here in Brokewood-on-Tandle. Granny had never taken it down. Mum’s room.

She tensed her hand, about to twist the doorknob, when out of the corner of her eye she saw something.

It was a person. Quietly slipping from the secret room and easing the door shut behind them.

Hattie stared.

The stranger wore an oversized red raincoat with the hood pulled up. They looked sturdy but light on their feet. Whoever it was, they must have been hiding there, somewhere in the shadows behind the desk. Waiting for Hattie and Jonathan to leave.

‘Hey,’ Hattie tried to say. But the word died in her throat. She coughed. ‘Hey! Er … hello?’

23The stranger flinched, glanced over a shoulder.

Eyes glinting in the moonlight. Dark skin. Close-cropped hair. A boy’s face.

Then, suddenly, not.

The boy transformed in an instant. He grew huge, muscles swelling to impossible size, body bulking until it filled the raincoat, stretched it tightly across a hunched, hulking back. He was enormous now, almost too big to fit on the landing.

The floorboards squealed and groaned at the weight.

Hattie gasped. His face was different now too. It had no nose at all, no mouth or eyes. It was rugged and textured, with a glint of crystal here and there, like nothing so much as a chunk of solid rock.

She must have imagined the boy she had thought she had seen. Because this person – this intruder – was clearly a massive man, wearing a terrifying stone mask.

Not that it made her feel any better.

The man lifted a fist the size of a football, and slammed it into the window.

Bang! The glass shattered with a sound like a gunshot. Cold air came rushing across the landing. Then with a cracking, a snapping and a scraping, the giant man heaved himself through. His legs were like heaps of rocks, piled one on top of another.

Thump! The whole house trembled as the man dropped and landed, unseen, on the ground below.

24Heart hammering, Hattie staggered to the window.

There he was, getting up from the bumpy, overgrown lawn at the back of the mill, amidst a scatter of glass shards. He began to run. The red raincoat flew out behind him, and Hattie felt another stab of shock as she saw the body beneath, large wedges of grey muscle stacked like – exactly like – slabs of stone.

The monstrous stone man darted beneath the branches of a big weeping willow at the back of the garden. He splashed through the Tandle. Then he was gone, dripping, into the woods. And there was nothing left but the darkness, and the rain, and the river still flowing fast.

Hattie took a step back from the window. She felt weak and shaky. It had happened so fast, she wanted to believe she had imagined it all. But the window really was broken. And underneath it, the floorboards really were cracked and dented.

‘Hattie?’ Footsteps came thumping up the stairs. Then Jonathan charged onto the landing, hefting a double-handed broadsword.

Hattie blinked. ‘Where did you get that?’

Her brother stopped and let the sword fall point first towards a floorboard. The long arms of his monkey hat swayed as he panted. The sword was almost as tall as he was, with a worn leather hilt and a steel pommel and an alarmingly battered blade. ‘Found it,’ he gasped, his 25shoulders heaving. ‘In the hall. With the umbrellas. It’s cool, isn’t it?’

‘No,’ said Hattie firmly. ‘Not cool. Incredibly dangerous. Put it down.’

‘Pffft,’ said Jonathan. ‘I bet Granny uses it for peeling potatoes.’ But he let the sword drop, with a clank, on the floor. ‘I heard you talking to someone. Was it a burglar? Should I chop his head off?’

‘Jonathan! Hattie!’ Dad’s voice. A moment later he appeared on the landing too, still holding his phone. His eyes widened as they fell on the sword, then the broken window. ‘What’s going on?’

‘There was a burglar!’ said Jonathan. ‘Hattie scared him off.’

Dad’s gaze fixed on Hattie. She nodded dumbly.

In the moonlight, Dad’s expression was so shocked it was almost comical, but Hattie didn’t feel like laughing. ‘Did you get a good look at him?’ he said at last.

Hattie opened her mouth, then closed it again. Yes, Dad, she imagined saying. He was a boy at first. But then he magically turned into a stone man, with piles of rocks instead of arms and legs, and a big slab of granite for a face.

Dad would never believe that. Obviously – because it was nonsense, wasn’t it? Stone men didn’t exist. Unless you counted statues, and they hardly went around breaking into people’s houses. The whole thing must have been a trick of the moonlight.

26The burglar was an ordinary man – big and scary, but a man all the same.

He had to be.

‘He was sort of … large,’ she said at last. ‘Oh – and he had a red raincoat.’

Dad started tapping at his phone, his face lit up in its pale glow. ‘All right, team,’ he said. ‘Everyone stay calm. I’m going to call the police.’

Chapter 4

TWIGS

Forty minutes later the Amiri-Gavells were standing in the entrance hall of the Tawny Owl, Brokewood’s only Bed & Breakfast.

Mr Nicholls, the owner, took Dad’s suitcase and led them up the narrow staircase to their rooms, which turned out to be completely full of porcelain owls. They cluttered the mantelpiece, the dresser and the bedside tables. The dark green bedspreads were patterned with flying owls too, and the heavy curtains matched. Dust hung in the air, thickly coating the lampshade, the faded brown carpet and the peculiar ornaments.

‘Is the whole place, er … like this?’ asked Dad.

‘Oh yes,’ said Mr Nicholls cheerfully. He was a small, round man with black-framed glasses and a sweater the colour of mud. ‘And look, by the sink. An owl-shaped toothbrush holder! Funny, isn’t it?’

‘No,’ said Jonathan.

Dad coughed and apologized.

‘Well, blame my wife,’ said Mr Nicholls. ‘I always do. 28Breakfast is from seven till nine.’ He closed the door and left them to it.

Jonathan launched himself onto the bed and began to unpack the hot, greasy parcel of fish and chips they had bought at a little takeaway beside the post office.

‘Let’s make the best of it, team,’ said Dad, going to help him. ‘We’ll feel better with a bit of food inside us, just you wait.’

‘What if Granny comes home, and we’re not there?’ asked Hattie.

Dad waved his hand distractedly. ‘It will be fine. I’ve left a note asking her to call us right away. The police said to stay here for the time being.’

Hattie nodded. It would hardly have been a surprise that Dad didn’t want them to spend the night at Granny’s house, even without the strange burglar. A cold, shivery feeling ran through her at the thought of him.

They all settled cross-legged on the bed to eat, but Hattie found that she wasn’t hungry. She dabbed a chip into the little puddle of ketchup, and left it there.

‘Listen,’ Dad said, after they’d been picking at the food for a while. ‘I know you’re both worried. But I promise this will all be fine. The house is safely locked up now. The sergeant’s going round to check on it and take a look at that broken window. And I’m sure that Deirdre will show up soon, but if we haven’t heard from 29her by the morning, I’ll go to the station and we’ll get it sorted. Any questions?’

Jonathan stuck his hand up. ‘Can I watch TV?’

‘Sure.’

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)