3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Sprache: Englisch

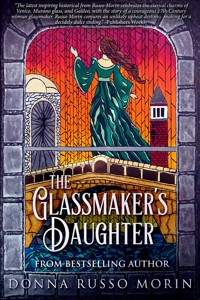

She was the only woman in Venice who knew the secret...and it made her a criminal.

The Murano glassmakers of Venice are celebrated and revered. But now three of them are dead, killed for attempting to leave the city that both prizes their work and keeps them prisoners. For in the 17th century, the secret of their craft must, by law, never leave Venetian shores. Yet there is someone who keeps the secret while defying tradition. She is Sophia Fiolario, and she, too, is a glassmaker. Her crime is being a woman.

Sophia knows her family would be crushed by scandal - or worse - if the truth of her knowledge and skill with the glass were revealed. But there has never been any threat...until now. A wealthy nobleman with strong connections to the powerful Doge has requested Sophia's hand in marriage, and her refusal could draw dangerous attention. Yet to accept, to no longer make the glass, would devastate her. If there is an escape, Sophia intends to find it.

Between creating precious glass parts for one Professore Galileo Galilei's astonishing invention and attending lavish parties at the Doge's Palace, Sophia crosses paths with influential people, including one who could change her life forever. But in Venice, every secret has its price. Soon, Sophia must decide how much she is willing to pay for her family, the glass, and love.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THE GLASSMAKER'S DAUGHTER

A NOVEL OF VENICE’S GLASSMAKERS

DONNA RUSSO MORIN

CONTENTS

Other Works by the Author

Praise for The Glassmaker’s Daughter

An Author’s Confession

Dramatis Personae

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

What Happened Next in Venice

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

A Reading Group Guide

You may also like

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2020 Donna Russo Morin

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Cover Design by CoverMint

Original Cover Painting by Donna Russo Morin (c)

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

Other Works by Bestselling Author

Donna Russo Morin

GILDED DREAMS

GILDED SUMMERS

BIRTH: Once, Upon a New Time Book One

PORTRAIT OF A CONSPIRACY: Da Vinci’s Disciples Book One

THE COMPETITION: Da Vinci’s Disciples Book Two

THE FLAMES OF FLORENCE: Da Vinci’s Disciples Book Three

THE KING’S AGENT

TO SERVE A KING

THE COURTIER OF VERSAILLES

PRAISE FOR THE GLASSMAKER’S DAUGHTER

(formerly The Secret of the Glass)

“One of the best written novels of Venice I have ever read.”

-HISTORICAL NOVEL REVIEW

“The latest inspiring historical from Morin celebrates the eternal charms of Venice, Murano glass, and Galileo, with the story of a courageous 17th Century woman glassmaker. Morin conjures an unlikely upbeat destiny…making for a decidedly dulce ending.”

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

“History comes to life! Like brilliant glass, her story swirls together colors of political and religious intrigue, murder and romance. Readers will be enmeshed in the lives of her fascinating characters.

-RT REVIEWS

“Filled with characters that are easy to like and a plot that twists and turns through history to a most satisfactory conclusion. Wonderful 5-star historical fiction.”

-ARMCHAIR REVIEWS

“Absolutely superb! Russo Morin does a spectacular job…a phenomenal historical fiction tale about an often disturbing time period. Outstanding Pick for 2010.”

-BOOK ILLUMINATIONS

“A beautiful story by master storyteller Donna Russo Morin; a tale that should not be missed.”

-SINGLE TITLES

“With elegant prose and alluring style, Donna Russo Morin brings 17th century Venice gloriously to life.”

-HISTORICAL FICTION.COM

“Highly recommended!”

-HISTORICALLY OBSESSED

Best Books Award Finalist: USA Book News

2010 Single Titles Reviewers' Choice Award

To my parents, my mother, Barbara (Petrini, DiMauro) Russo, and my father, the late Alexander (DeRobbio) Russo, for their love and devotion, for the Italian heritage of which I am so proud, and for the work ethic that has served me so well…

… and for my sons, Devon and Dylan, Always.

AN AUTHOR’S CONFESSION

I never planned to produce a revised version of this, my second book, originally released in 2010. I never expected that I would ever get this book written in the first instance. While I was fulfilling a contract to do so, my marriage was ending in the worst possible way. I was actually at the computer, writing this book, when the final decision rushed through me, careened from me.

I kept writing this book through the beginning of a horrid divorce, a demoralizing procedure that lasted seven and a half years. That I wrote not only this book but many more during that time still surprises me to this day.

At the end of this tale is my original Acknowledgement. In it, I make a vague reference to my muse. I’d like to make that less vague.

Teodoro is modeled after two men, both bearing the name Tom. The first is Tom B. Yes, that Tom B. He and the other wonderful New England Patriots brought me the definitive escapism from my troubled world. They gave me something to look forward to every week when there was nothing true to look forward to in it. They gave me something to hold onto…hope. Tom B’s determined and beautiful masculinity was a perfect model for Teodoro. But he was not alone.

There was another Tom in my life at that time, another gloriously handsome Tom. And while wholly innocent because of the nature of my situation, Tom G. also gave me hope…hope that at the end of all my tribulations, there could be something wonderful waiting on the other side…hope that while I was then in my fifties with two almost-grown sons, I was still a woman, I was still womanly.

The hope these two Toms gave me infused me with the ability to forge on, to be determined, and to find the core of strength deep within me. Ten books later, that strength and hope still serve me well.

To both men…thank you.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

*denotes historical character

SOPHIA FIOLARIO: Nineteen years old; the eldest daughter of Zeno Fiolario.

ZENO FIOLARIO: Glassmaking maestro and the owner of La Spada glassworks on Murano. VIVIANA, ORIANA, LIA, and MARCELLA FIOLARIO: Wife, sisters, and grandmother of Sophia

*LEONARDO DONATO: Ninetieth Doge of Venice; served from 1606 to 1612.

PASQUALE DA FULIGNA: The only son of a poor nobleman.

*GALILEO GALILEI: Physicist, astronomer, mathematician, and philosopher; born in Pisa.

*PAOLO SARPI: Venetian-born Servite friar, scholar, and scientist who served as a canonist and theological counselor for the Venetian Republic.

*GIANFRANCESCO SAGREDO: Venetian philosopher, diplomat, and libertine.

TEODORO GRADENIGO: Youngest son of a poor nobleman from the Barnaba area of Venice.

ONE

Scalding heat rose up before her, reaching deep inside like a selfish lover grasping for her soul. Fiery vapors scorched fragile facial skin. Yellow-orange flames seared their impression in her eyes.When she pulled away, when she finally turned her gaze from the fire, her vision in the dim light of the stone-walled factory would be nothing more than the eerie specters of the flames’ flickering tendrils.

Sophia Fiolario performed the next step in making the glass in an instant of time, instincts and years of practice led the way; from the feel of the borcèlla in her hand, from the changing odor, to the color of the molten material as it began to solidify.

The crucial moment came; the glass barely still liquid…on the precipice of becoming a solid. Then, and only then, did she use her special tongs to conceive its ever-lasting form. If she didn’t perform perfectly, if her ministrations were inelegant or slow in this tiny void of time, she would have to start again.

The layers of clothing encasing her body wrapped the heat of the furnace around her. With a stab of envy, Sophia pictured the men of Murano who worked the glass, clad in no more than thin linen shirts and lightweight breeches. As a woman, forbidden to work the furnaces, particularly during these prohibited hours after the evening vigil’s bells, she had no choice but to stand before the radiating heat clad in chemise and gown.

Sweat pooled beneath her breasts and trickled down the small of her back. Down her forehead, perching precariously on her brow. Within minutes of stepping into the circle of the furnace’s sweltering air—a heat over two thousand degrees—sweat drenched her. Her body’s pungent odor soon vied for dominance over the caustic scent of melting minerals and burning wood.

Sophia pulled the long, heavy blowpipe out of the rectangular door, the ball of volcanic material retreating last. With a mother’s kiss, she put her lips to the tapered end of the canna da soffio and blew. As the ball of material expanded and changed, she knew the thrill unlike any other she’d known in all her nineteen years.

The time came…the moment. She brought the glass to life. The malleable substance glowed. The once-clear material absorbed the heat of the flames, turning fiery amber. It waited for—longed for—her touch as the yearning lover awaits the final throes of passion.

Quickly Sophia spun to her scagno, the uniquely designed table. She sat on the hard bench in the U-shaped space created by two slim metal arms running perpendicular to the bench on either side of her. Placing the long ferro sbuso across the braces, her left palm pushed and pulled against it, always spinning, always keeping gravity’s pull on the fluid material equal. With her right hand, she grabbed the borcèlla and reached for the still-pliable mass.

For a tick, she closed her eyes, envisioning the shape. When she looked up, it was there on the end of her rod. She could see it, therefore she could make it. Sophia set to her work.

The man moved out of the corner’s shadows. Sophia flinched. He’d been quiet for so long, she had forgotten him. As he stood to stoke the crugioli, she remembered his presence and felt glad for it.

Uncountable were the nights they had worked together like this. From her youngest days, he had indulged her unlawful interest in the glassmaking, teaching and encouraging her, until her skills matched those of his—Zeno Fiolario, one of Venice’s glassmaking maestri, her papa.

Zeno moved from furnace to furnace, adding the alder wood wherever needed, checking the water in the many buckets scattered through the factory. The glow of the flames rose and spread to the darkest corners of the stone fabbrica. The pervasive, sweet scent of burning alder tree permeated the warm air. For his daughter, Zeno often fulfilled the duties of the stizzador—the man whose sole function was to keep the fires of the furnaces blazing—and his old frayed work shirt, nearly worn out in spots, bore the small umber marks of the sparks that so frequently leaped out of the crucibles.

He shuffled about slower than in years past, with shoulders permanently hunched from so many years bent over the glass. Yet he jigged from chore to chore with surprising agility. As he made his way past his daughter, Zeno brushed a long lock of her deep chestnut hair away from her face, thick and work-roughed fingers wrapped it behind her ear with graceful gentleness. The touch succor to her soul and a jolt to her muse. Her wide mouth curved in a soft smile; her large, slanted blue eyes remained focused on the work before her.

“It was the Greeks you know…uh, no,” her father began, faltered, tilting his head to the side to think as he often did of late.

Sophia nearly rolled her eyes heavenward as young people are wont to do when their elders launched into an oft-repeated tale, but she stifled the impulse. She could have finished the sentence for him; she’d heard this story so many times she knew it by heart. She gifted her father the silence to tell it at his own pace.

She would work, he would talk, and though he feigned unconcern for her methodology, his narrow, pale eyes, framed by thick gray lashes, followed each flick of her wrist, each squeeze of her pinchers. Her smile remained, dampened by but a twinge of impatience; she had learned too much, been loved too well by this man to begrudge him his rapt study of her work.

“The Phoenicians, that’s it,” Zeno’s voice rang with triumph. “They had been merchants, traders of nitrum, taking refuge on the shore for the night. They could find no rocks to put in their fires, to hold their cooking pots. So they pilfered a few pieces of their own goods.

“This was years and years before the birth of our Lord and they were simple, uneducated people. When the clumps of nitrum liquefied and mixed with the sand, the beach flowed with trickles of transparent fluid. They thought they witnessed a miracle, but they were seeing glass…the first glass.”

Her father’s voice became a cadence, like the lapping of the lagoon waves upon the shore that surrounded them; its rhythmic vibrato paced her work. Her left hand twisted the ferro sbuso while the right manipulated the tongs…pinching here, shaping there.

“Our family has always made the glass. Since Pietro Fiolario’s time four hundred years ago, we have guarded the secret.”

Sophia stole a glance at him; young eyes found the old and embraced in understanding. This secret had been the family’s blessing as well as its curse. It had brought them world renown and an abundance of fortune greater than many a noble Venetian family. And yet it had made them prisoners in their homeland, and Sophia, a woman who knew the secret, doubly condemned.

Time became Sophia’s rivals; the glass grew harder and harder to contort with just gentle guidance. Already its form was a visual masterpiece…the delicate base, the long fragile flute, the bowl a perfectly symmetrical shape. Her hands flew, waves undulated on the rim; she captured the fluidity to the rapidly solidifying form.

A deep sigh, an exhalation of pure satisfaction. Sophia straightened her curled shoulders, bending her head from side to side to stretch tense neck muscles, tight from so long in one position. She studied the piece before her, daring to peek at her father. In his eyes glowing with pride, she saw confirmation of what she felt, already this was a remarkable piece…but it was not done yet.

“Now you will add our special touch, sì?” her father asked as he retrieved the special, smaller pinchers from another scagno.

This smile of Sophia’s came from indulgence. Keeping alive the delusion for her father was yet another small price to pay him. The technique she would do next, the a morise, to lay minuscule strands of colored glass in a pattern on this base piece, had made their fabbrica famous. Since its release to the public, her father had reveled in the accolades he received over its genius and beauty. Her father had never, could never, reveal that the invention had been Sophia’s.

“Sì, Papa.” Sophia lay down the larger tongs, flexing the tight muscles of her hands. She gathered the long abundance of brunette hair flowing without restraint around her shoulders, unbound from its usually pulled-back style, and laid it neatly against her back and out of her way. Taking up the more delicate pinchers from her father’s hand, she rolled her shoulders once more and set to work.

Zeno hovered by her shoulder, leaning forward to watch as her long, slim hands worked their magic, as she wielded the pinchers to apply the threads of magenta glass, smaller than the size of a buttercup’s stem, in precise, straight lines. Dipping the tip of the tweezer-like device into the bucket of water at her feet, releasing the hiss and smoke into the air, Sophia secured each strand with a diminutive drop of cool moisture.

“A little more this way,” Zeno whispered, as if to speak too loudly would be to disturb the fragile material.

“Yes, Father,” Sophia answered automatically.

“It’s patience, having the patience to let the glass develop at its will, to cool and heat, cool and heat naturally,” Zeno chanted close to her ear, his voice—the words—guiding her as they had done she was young. His muted voice small in the cavernous chamber; their presence enveloped by the creative energy. “As the grape slowly ripens on the vine, the sand and silica and nitre become glass on the rod. Ah, you’re getting it now, bellissimo.”

“Grazie, Papa.”

“Next you’re going to—”

The bang, bang, bang of a fist upon wood shattered the quiet like glass crashing upon the stone. The heavy wooden door at the top of the winding stairs jangled and rocked. Someone tried to enter, yet the bolted portal stymied the attempts, locked as always when father and daughter shared these moments.

Zeno and Sophia stiffened, bulging eyes locked.

“Are we discovered?” Sophia’s whisper cracked, strangled with fear. She shoved the rod into her father’s hands, dropping the slender mental pinchers on the hard stone floor below, wincing at the raucous clang that permeated the stillness.

“Cannot be.” Zeno shook his head. “It can no—”

“Zeno, Zeno!” The urgent, distraught male voice slithered through the cracks of the door’s wooden planks. “Let me in.”

Parent and child recognized the tone; Giacomo Mazzoni had worked at the Fiolario family’s glassworks since he was a young man, his relationship evolving into that of a dear and familiar friend. The terror in his recognized voice undeniable; the strangeness of his presence at such a late hour was nothing short of alarming.

With an odd calmness, Zeno pointed toward the door. “Let him in, Phie.”

The dour intent upon her father’s wrinkled countenance screamed that he would brook no argument. Gathering the front of her old, soiled gown, she sprinted up the winding stairs, glancing back at the wizened man who stood stock still, rod and still in hand.

Sophia pushed aside the bolt with a ragged, wrenching screech. The door gave way the instant she freed it. Giacomo rushed in, pushing past Sophia where she stood on the small platform by the door. Clad in his nightshirt, a pair of loosely tied knee-breeches flapping around his legs, he looked a fright with his short hair sticking out at all angles, and his black eyes afire…fear-ridden. Flying down the stairs, he ran to his friend and mentor, grabbing him by the shoulders.

“They’re dead, Zeno. Dead.”

Zeno stared at his friend as he would a stranger, pale eyes squinting beneath his furrowed brow. “Who, Giacomo? Who is dead?”

“Clairomonti, Quirini, Giustinian, those who tried to get to France.”

“Dio mio.” The words slithered from Zeno’s lips as his jaw fell. His legs quivered beneath him visibly. With a shaking hand, he reached into empty air, groping for a stool.

Rushing to his side, Sophia grabbed the wooden seat, yanking it forward, and guiding her father into it with a hand on his arm.

Zeno looked at his beloved daughter’s face. Once more, their eyes locked, frozen by fear. “They have killed them.”

TWO

They entered through the bell tower entrance, their footfalls echoing off the marble floor to rise up into the tall, confined space of Santo Stefano’s brick campanile. Dawn’s pale light kissed the land and the toll of the bells summoning all to work reverberated in morning’s fresh air. The warmth of the late spring day had not yet crept in to muffle the mesmerizing sound.

Men of all ages, shapes, and sizes filed in; their wondrous diversity as varied as their styles. Some wore the grand fashion of the Spanish, with embroidered doublets, sword and dagger hanging from their waist. Long hair flowed past their shoulders and thin mustaches or goatees adorned their faces.

The less ostentatious wore simple linen or silk shirts and breeches, with plain but elegant waistcoats. From the chins of the older, mostly bald gentlemen hung long, dignified beards. The younger, still pretty men preferred clean faces and closely cropped caps of hair.

They converged from almost every glassworks on the island, the owners and their sons, concern and fear tempering any joy to be had in their assembly.

The sun hovered at the horizon now, its rays imprisoned by the close-set buildings, and the gloomy shadows clung to the parish church’s interior. In the muted light, the solemn procession soon filled the pew’s wooden benches. These men, the Arte dei Vetrai, represented the members of the glassworkers’ guild. This league of artigiani united in self-preservation, to provide aid for the sick and aged in their profession as well as the widows and children of their lost loved ones.

Somber whispers rumbled through the incense laden air, a remainder of dawn’s devotions. In Murano, as in other parishes of Venice, there stood as many churches as there were winding canals. The Arte had chosen Santo Stefano as their home decades ago, selected for its simple grace and its centralized location on the Rio de Vetrai, the main canal running through the glassmaking district. Legend held that it had been built by the Camaldolese hermits at the time of the millennium, restored and renovated many times since.

A gavel’s hard rap upon the podium broke the quiet discourse; Domenico Cittadini, the owner of the Leone d’Oro glassworks and steward of the Arti, called the meeting to order.

“It is with great sadness that we come here today to discuss the deaths of our colleagues Hieronimo Quirini, Norberto Clairomonti, and Fabrizio Giustinian.”

“Parodia! Terribile! Orrible!”

Outraged shouts cracked like thunder, ricocheting against stone walls, lofting to the high, vaulted ceiling, and out the windows where the women of the town stood and listened. Huddled together, their heads straining to get as close to the partially opened windows as they could.

“Silenzio!” Cittadini countered their din. Veins pulsed on his forehead, splotches of red burst upon his olive skin, dark eyes bulged under thick salt-and-pepper brows. “The Capitularis de Fiolarus is clear.”

He threw a thick wad of string-bound vellum on the floor. The men in the front pews flinched away from the loud thwack. The statutes imposed upon the glassworkers by the Venetian government were a long, imposing list.

“I am as ravaged by their demise as any of you, but our lost brethren knew what could happen when they left for France, when they allowed the foreign devils to entice them away with promises of riches and fame.”

The denunciation of the dead hung heavy in oppressive silence; almost two hundred men swallowed their distaste upon their tongues with respect for their leader. Cittadini had served but two months of his one year, elected stewardship, but he shouldered his duties with supreme dedication.

From the back of the church, wood creaked as a slight, elderly man rose, unfurling his curved and bent body as he slid a blue silk cap from his balding pate. Every head swiveled to the sound. Every ear strained to hear what Arturo Barovier, a descendant of one of the greatest glassmaking families in the history of Murano, had to say.

“For over two hundred years they have kept us prisoner and now they have killed.” His voice warbled like birdsong. “We must tolerate this no longer.”

Impassioned, angry diatribes erupted. Scarlet-faced men pointed fingers at one another, punctuating their arguments. Any semblance of order dispersed like smoke on the breeze of discontent. They did not debate the existence of the restrictive government control but whether or not it was warranted. Under the guise of protection, La Serenissima—the government of the Most Serene Republic of Venice—began its meticulous ascendancy of the glass working industry nearly four centuries ago. A fanatical Republic ruled by perversely tyrannical patriots, they deemed no action egregious did it benefit the State.

Their control spread as did the renown of Venetian glass. They spoke of fear for the growing population living in mostly wooden structures, the risk of fires posed by the glassmaking furnaces. The decree restricting all vetreria to the island of Murano came late in the thirteenth century and the virtual imprisonment of the glassmaking families began. The regime’s sophistry was an ill-fitting disguise; its true intention soon became clear.

Greed not safety motivated the regime’s concern. They meant to isolate the glassworkers, to inhibit any contact they might have with the outside world. As time passed, the pretense fell away; clear, unmistakable threats of bodily harm were made to any defecting glassworker and their families. The isolation intended—first and foremost—to protect the secret of the glass. That and nothing else, for the exquisite vetro of Venice brought the State world fame and filled the government’s coffers with overflowing fortune.

The statues of the Captularis quickly swelled to include the Mariegole, a statement of duty for all glassworkers. It told them who was allowed to work and when, when the factories could close for vacation and for how long, going so far as to dictate how many bocche a furnace must have as if the government knew better than the workers the best number of windows a crucible needed.

Now, in these infant days of the seventeenth century, the State’s malicious control had surpassed all acts that had come before; their hand of power had turned into a fist, one ready to pummel anyone who publicly defied them.

Sophia inched closer to the brick-trimmed opening as she could, straining on the tips of her toes as she nodded her head in silent, fervent agreement with Signore Barovier’s sentiments. As a woman, she could only make the glass—indulge her one true passion—in secret, another of the Serenissima’s dictates. She cared nothing for their dictates, held the politicians themselves in no esteem.

“Shh,” she hissed at the murmuring women around her, a pointed finger tapping against her pursed lips. She surprised everyone—herself included—with her boldness, too desperate to hear to remain hidden in her usual timidity.

Inside, Vincenzo Bonetti stood up, long face and nose bowed, one of the youngest men there but still the padrone of the Pigna glassworks. “I would like to hear what Signore Fiolario has to say.”

Wood groaned, fabric rustled; all eyes looked to Zeno, quiet, so far, amidst the boiling discussion.

The men often looked to Zeno for his counsel. Though he had not been the steward of the Arti for almost ten years, many considered him the best there had ever been; many still sought his wisdom like the child seeks approval from the parent. Like the others before him, Zeno stood, twisting his thin body to face the assemblage.

The morning sun’s first rays found the stained glass of the long, arched altar window. A burst of colorful streaks illuminated Zeno’s angular features with hues of shimmering moss and indigo. He appeared like a colorful specter, prismatic yet surreal.

“We are like precious works of art, cloistered in locked museums, trotted out for show when visiting royalty appears but kept behind bars otherwise.”

“Sì, sì,” incensed, agreeing cries rang out. Heads waggled in agreement, hands flew up in the air as if to beseech God to hear their entreaties.

Time after time, the Serenissima flaunted the talent and wealth of Venice in the faces of sojourning royalty, using the artisans of Murano for audacious displays. Not so long ago King Henry III of France had been the most exalted guest of the Republic. Many prestigious members of the Arte had been ceremonial attendants, including a younger Zeno just achieving the apex of his artistry, participating in exhibitions for the delight of the visiting monarch.

At the sound of her father’s voice, Sophia strained her toes, her neck, to see in the high windows. She waited now in rapt attention for Zeno’s next wise dictum.

Her father stared at the expectant faces all around him. His lips floundered, but no words formed. His head tilted to the side and his gaze grew vacant. He looked down at the space on the pew beneath him and, without another word, sat down.

Sophia released her straining toes and leaned back against the warm brick of the church. Her face scrunched; she didn’t understand why her father did not say more. He looked as if he would, but the words had been lost on the journey from brain to lips.

Inside the church, the same confusion cloaked the congregation; men shared their bewilderment in silent glances, faces changing in the shifting shadows as the rising sun found the windows and streamed in.

Cittadini took advantage of the lull. Stepping out from the podium, he crossed the altar and stood in line with the first of the many rows of blond oak pews, at the intersection of the forward and sideward paths.

“Tell me, de Varisco,” the steward addressed a middle-aged man sitting close to the front, Manfredo de Varisco, owner of the San Giancinto glassworks. “You are not a nobleman, yet you live in a virtual palazzo. You own your gondola, sì?”

De Variso nodded his head, dirty blond curls bouncing, with an almost shameful shrug.

“And you, Brunuro, you are always wearing your bejeweled sword and dagger.” Cittadini strode down the aisle, approaching a handsome man, black-haired and ruddy, sitting a third of the way down. Baldessera Brunuro, with his brother Zuan, ran both the Tre Corone and the Due Serafini.

“Would you enjoy such privileges, such luxuries, if you were not glassworkers?”

No one spoke, though many shook their heads. The answer was most surely no; other Venetian members of the industrial class did not—could not—relish such refinements as did the glassmakers.

Jerking to his right, the robust and round Cittadini raised an accusing finger, pointing to another middle-aged man, one with finely sculpted features, the owner of Tre Croci d’Oro. “You, above all, Signore Serena, your daughter is to marry a noble. Your grandchildren will be nobles. For the love of God, your male heirs may sit on the Grand Council, may one day become Doge, Il Serenissima, the ruler of all Venice!”

Cittadini punctuated his impassioned plea, throwing his hands up and wide with dramatic finality.

Serena’s brown eyes held Cittadini’s, beacons shining from out of puffy, wrinkle-rimmed sockets. He struggled to stand, long white beard quivering from his chin onto his chest. For a few ticks of time, he held the steward’s attention in a unnatural quiet. The women outside captives, their noses pressed to the sills, all fussing and fluttering ceased once and for all.

“None of us wants to give up these things, these glories that make our lives so rich, so abundant,” Serena spoke of splendors yet with a brow furrowed, a frown upon thin lips. “But at what price? It is naught more than extortion. We should be—we must be—able to live as we please, go where we please. We have earned the right.”

Cittadini didn’t answer. He studied the face of a man he called friend. He turned, impotent, to the righteous faces all around, curling broad shoulders up to his ears. “Then…what are we to do?”

Within a house of God, amidst the aura of His benevolence, not a one of them had an answer.

THREE

Sophia stood at the tip of the eight-oared barge sailing at full tilt across the two kilometers of lagoon lying between Murano and the central cluster of the Venetian Islands. The wind blew against her face, lapping at the long folds of her best silk gown. At the rail beside her stood her two younger sisters, as eager and excited as she to reach the main island’s shore, to immerse themselves in the grandeur of Festa della Sensa. Somewhere on board the crowded transport, her mother, father, and grandmother mingled and gossiped with friends and relations, exuberance tempered by lifetime experience of the yearly celebration. The low flat islets of Venice appeared on the horizon as spiny church spires and round domes of cathedrals rose up like mountain ranges on the sea level earth. “Which kings and queens will be here do you think, Sophi? Which princes?” Oriana asked, lips close to her sister’s ear, thwarting the greedy breeze from snatching her words away.

Sophia grinned at Oriana; the seventeen-year-old’s exhilaration dispelled her often older womanliness. Rarely did Sophia feel like Oriana’s older sister. For a girl who had just attained marriageable age, Oriana’s dreams and fantasies of finding a noble husband never ended, never strayed. Sophia thought her charming, thought both her sister charming.

Oriana’s face held her own features, the same light blue eyes, the same chestnut hair. But on Oriana, Sophia thought them more delicate, a refined beauty rather than her own rustic plainness. Fourteen-year-old Lia still resembled that young a girl, but one with just a hint of promise at the woman she would become; she possessed not only her mother’s golden russet eyes but the natural golden copper hair so coveted by the women of Venice.

Sophia leaned close to their sparkling, captivated faces, squinting against the sun’s rays glinting off the ocean’s waves. In the incessant, potent rhythm of the barge’s oars, she heard the rhythm of her aroused heartbeat.

“One never knows which great personage will make an appearance at the Wedding of the Sea. They come from every corner of the world…France, England, Germany, sì, but China and India too.”

Her sisters squealed and giggled, clasping hands, and bouncing up and down. Sophia laughed with them; she loved them so much, to delight them was to delight herself.

The boat passed San Michele, and their laughter waned, they crossed themselves. This tiny square patch of land lay between the glassmaking center and the Rialtine group of islands, those forming the central cluster of Venice. San Michele might be its name, Venetians knew it as Cemetery Island.

Sophia made this short journey often; just as often she pondered what wonders of God created such an unparalleled anomaly as was her homeland. Much of the saltwater in the five hundred square kilometers of the Laguna Veneta was but waist-deep. Like the strands of a spider’s web, deep channels crisscrossed the water, allowing the heavy traffic through the waterways. Halfway between the mainland and the long, thin sandbanks known as the Lido, little islets of sand and marram grass had formed in the shoals as rivers and streams, like the Po and the Adige that ran down the Alps, discharged their silt. Over hundreds of years, each grain gathered, forming the world’s most uniquely beautiful, populated landmass.

Sitting snugly between Europe and Asia, Venice had held the purse strings of the world for centuries, reaping the benefits of her prime location by controlling its trade. At one time, not so long ago, it was more populated and productive than all of France, though equivalent to a quarter of its size. As new trade routes had opened, Venice’s power began to wane; its splendor and bounty and obsession with the best of everything the world had to offer continued to reign supreme. Its glitter had not yet begun to tarnish.

The passengers’ rumblings rose to raucousness as the boat pulled into the dock at the Fondamenta Nuove, depositing them at the largest landing stage in the north. The journey from here to the Bacino di San Marco, the basin at the eastern end of the Grand Canal, would be quicker and easier via canal and calle than to continue the journey upon the barge which would have to round the island’s jutting eastern tip.

The girls rushed from the vessel with unladylike haste, lingering with jittery impatience at the water’s edge for their family. Their formal summer gowns flapped like the wings of harried birds in the constant breeze wafting off the sea. Sophia in simple crème while her sisters popped in peony and aquamarine; her modest, almost severe hairstyle looked even plainer in contrast to their braided, pinned, and beribboned coifs. All three faces shone bright like glass beads beneath their small, lacy white veils obscuring their maiden faces.

The sisters pointed and gaped at the breathtaking beauty of the city, decorated in its finery for the ceremony and all the visitors it brought. The pale pink and flax stone buildings blossomed with flower boxes, a riot of color on balconies and rooftop altanes. The storied buildings seemed made of row upon row of lace, each row unique in itself. The graceful multi-shaped windows, spiny-topped roofs, gothic arches, and marbled columns shone twice in their reflections off the shimmering, undulating surface of the canal water at their feet. Blooming garlands festooned doors; servant in fine livery stood poised to greet any guests.

A pulsing, never-ending mass of people swirled and jostled the sisters; westerners in familiar attire, easterners in exotic saris and turbans…a painter’s palette of colors. Oriana spied her elders among the thinning throng trailing off the barge.

“Papa, Mamma, Nonna,” she called, waving her hand high above her head, gestures ever more expansive as Sophia shushed her.

“Sì. Hurry, hurry.” Lia picked up where Oriana left off, laughing as Sophia punished her with a scathing sidelong glance.

The elder Fiolarios waved back, making their way to the shore in their own good time; no matter how fast they moved it would not be fast enough for their excited children.

At the end of the ramp, Zeno gathered his family, putting on the silk cap that would protect the tender skin of his thinly-haired pate.

“We shall take a gondola today, sì? All the way to the piazza.” His pale eyes sparkled below bouncing brows.

“Zeno!” His wife’s shocked gasp rose above the trill of her daughters. Viviana Boccalini Folario’s elegant, dark features—still distinctive and beautiful as when she’d been a girl—blanched. She took three quick steps toward her husband. Even in her trepidation, her curvaceous figure moved with grace, hips swayed with seduction so particular to the women of the Adriatico.

“Is such expense necessary? All the way to the ceremony, even along the Canale Grande? Should we spend that much soldi, that many ducats?” She tortured her husband with a dark gaze, one particular from a wife to an errant husband. It held little of its power this day.

“Now, cara,” Zeno purred, slipping his wife’s hand over his thin, chiseled arms and that of his mother over the other. “Our profits have been larger than ever this year and today is one of the most profound for our people. If not today, when, eh?”

“Sì, Viviana,” Marcella piped in. “It would be so nice for these old legs to rest while they can today.”

Viviana cocked her head at her mother-in-law, a brow quirking upward. As strong and hearty as Viviana herself, there was nothing elderly about this sixty-eight-year-old woman. Shorter and rounder than in years past, gray hair and the lighter skin she had given her son, Marcella still possessed a vigorous constitution. She found great pleasure conspiring with Zeno. With a shrug and a nod, Viviana capitulated. “Very well, off we go. Let’s eat at every trattoria and shop all day while we are at it.”

“Sounds perfect, mi amore,” Zeno countered his wife’s sarcasm with sincerity. Viviana’s jaw fell; Zeno’s face cracked with a sheepish grin. “Come, come, mia famiglia, this way.”

Zeno led the procession of women along the fondamenta, chest puffed up grandly…a rooster leading his hens. He nodded to all the men staring at his bevy of beauties with a skewed, cocky grin. They arrived at the small canal of the Rio dei Gesuiti and mingled into the gondola waiting line.

Venice’s winding waterways teemed with the long, narrow asymmetrical boats; close to ten thousands of them floated on the city’s greenish liquid arteries. Those privately owned, so many belonging to the rich and noble, distinctive with bright colors and opulent cloth felzi. All black ones in the thousands floated for hire. The Fiolarios did not have long to wait.

“Buongiorno, signore. Where may I take you and your beautiful family?” the dark-haired gondolier asked as he helped each Fiolario onto his craft with a firm, large hand. Oriana and Lia giggled at his touch, their young, hungry scrutiny devouring his sculpted muscles so perfectly displayed under his Egyptian blue, skin-tight jerkin and crimson hose.

“All the way to the piazza, if you please,” Zeno called out with spirit and smiled playfully at his wife. He wielded his natural charm and merriment, enticing Viviana to catch the festive mood as successfully as he had when first seducing her and winning her heart, enticing her away from her family to live the sequestered life with him on Murano. She was as enchanted now as then. With a small huff of surrender, Viviana relinquished and laughed along with her husband and Marcella as they took their seats on the cushioned bench closest to the gondolier.

“All the way? Madonna mia, how wonderful,” their gondolier cried, bowing low over an offered leg. “I am Pietro and you will have the most wonderful ride of your life.”

The beguiled Fiolarios applauded as Pietro set the oar into the forcola, the elaborately curved wooden oarlock, and began to drive the craft along.

“A-oel,” he cried with a singsong cadence, announcing their departure and alerting the oarsmen on the nearby gondolas of their launch.

The girls sat in front of their elders on their own pillowed row of seats, staring in wide-eyed wonder at the mass of people floating by on the canals and walking along the adjacent fondamenti. With a closed-eyed sigh, Sophia inhaled the aromas of cooking food, blooming flowers, and the ever-present dung-like earthy odor of the canals. How different the city seemed today than most, when she ambled along these passageways with one companion or another, conducting business on behalf of the glassworks and her aging father, who had no son to send in his stead. Her sisters turned and twisted in their seats, thrilled by the metropolitan sights so infrequently glimpsed, straining to see all its attractions, including their handsome boatman. They sighed with girlish exhalations as Pietro began to sing, his sweet tenor serenading them, the dulcet tones joining in the chorus with those of the other gondoliers.

As they turned off the smaller waterway and onto the Canalazzo, the modest and charming homes lining the jetty became large and magnificent palazzi. On their balconies and through their stained glass windows, Sophia spied the sumptuously attired nobles in various stages of party preparations.

Passing beneath the Ponte de Rialto, they circled back inland on smaller canals, their muscular gondolier crouching deep beneath the low footbridges that crossed the thin waterways. Like bright and garish blossoms, the courtesans festooned almost every bridge and many of the balconies throughout the city, their powdered breasts bulging from their scant bodices, their young skin hardened and lined by layers of rouge and paint. Upon the quaysides, they streamed through the crowds, the tarnished jewels of the Republic’s obsession with pleasure.

“You must hurry now,” Pietro urged as he brought his passengers to the dockside and helped them from his vehicle, accepting his fee from Zeno with a quick bow. “High Mass will begin soon.”

“Grazie,” Zeno and Viviana called together, corralling their family, and stepping briskly away from the water’s edge.

“Arrivederci, Pietro.” Oriana and Lia waved daintily over their shoulders.

“Ciao, bellezze.” Pietro smiled at them with a devil-may-care smirk, and Sophia grinned behind a hand as her sisters giggled with glee.

With the congested stream of people, the Fiolario family rushed into the stone-paved Piazza San Marco, the largest and most opulent open square in all of Venice. As the bells of the towering brick campanile began to peal, they surged forward with the jostling crowd toward the domed Basilica and its distinctive façade and huge golden domes that dominated the Venetian horizon. Squeezing tightly against the throngs of worshippers, the family filtered through the massive Romanesque arching doorways and into the glowing interior, illuminated by thousands of candles whose light reflected off the gold mosaics and colored marble.

Only a smattering of empty seats remained, and the girls surrendered them to their elders with respect. Standing in one of the many rows of people along the back, Sophia strained to see the front of the church. People filled every space of the building, uniquely designed in a cross of four equal arms, as opposed to the more popular Latin style found in most churches. She bowed her head to give thanks, allowing the chanting of prayers and singing of hymns to engulf and fill her. The cloying scent of the incense, emanating from the tendrils of smoke rising from the swaying, clacking gold censers, did little to mask the musky and bitter stench of so many bodies.

Sophia’s own whispered yet fervent prayers mingled with those of the hundreds of other parishioners. Her gratitude overwhelmed her, for the beauty of this day, the magnificence of her country, and, most of all, the love of her family. She felt a moment’s repentance, for choosing the life she had, for forsaking marriage and motherhood as both society and the church insisted was her duty. She squeezed her clenched hands together, feeling the slim, hard bones within them. God had given her the gift in these hands; surely he forgave her and loved her for using it.

Sophia sent a special prayer to Saint Mark, he who gave his life to spread the word of Jesus and whose remains lay entombed below them. His body—smuggled out of the heathens’ land by Venetian sailors and hidden amidst a cache of pork, rendering it untouchable to the Muslims—came to these shores hundreds of years ago, and his capacity to ignite the people’s passion remained as powerful as the day he arrived. He was their patron and the source of their strength.

The mass ended and cheerful voices joined rustling fabrics and the now restless and cramped congregation filled the aisles. Behind Doge Leonardo Donato, a tall, somber man and the Republic’s ninetieth ducal ruler, they emptied out into the already crowded piazza, where more celebrants, too many to fit into the Basilica, waited. Surrounded by black-robed senators and council members, bishops and priests, Doge Donato, sweating under full ducal regalia—a scarlet brocade robe, cape, and doge’s cap—strode past the Palazzo Ducale and into the smaller Piazzetta where they stopped between the two majestic marble columns.

The twelfth-century stone projectiles—“acquisitions” from Constantinople—marked the aperture of the Molo, the waterfront—the majestic gateway—of the grand city. Atop one stood the winged lion of St. Mark while upon the other St. Theodore, the former patron of the Republic, battled a crocodile.

Sophia refused to look up to the top of the long, bright stone pillars. As a frightened child, she had seen men hanging upside down from a gibbet strung between them, and the horrifying sight had forever blighted their beauty in her eyes.

The Fiolario women slowed as they neared the shore, but Zeno urged them on.

“No, not this year. Today we will not just watch. We will be a part of this celebration.”

He smiled infectiously, urging them forward through the teeming masses to the ramp of a plumed and festooned barge. He dug in his pocket for the many gold coins to pay the family’s fare. Viviana opened her mouth to protest, snapping her jaw shut, offering a serene, if forced, smile in place of any harsh words.

With a wave to the crowd packing the piazzetta and overflowing into the larger piazza, Doge Donato stepped through the mammoth arch formed by the columns to board the Bucintoro with his chosen special guests. Among the contingent were not only the most powerful senators and council members of the land, but also the visiting kings, queens, and princes that Oriana so longed to see.

She grabbed Sophia’s arm. “Can you see any of them?”

Both young women strained to see across the water from where they stood near the rail of their garlanded craft and onto the ceremonial galley.

Sophia pursed her lips and narrowed her eyes as she looked off into the distance. “Sì, I see someone. Oh, he is very handsome, very slim, and muscular. What’s this? He’s stopped … he’s looking around for … for something.”

“What?” Oriana popped with excitement. “Che cosa? What does he look for?”

Sophia stood on tiptoe and craned her neck back and forth to see over and around the heads in front of them. “He looks … he looks … for you.”

“Uffa!” Oriana slapped Sophia’s arm, annoyed but laughing.

“Shh,” Sophia insisted with an indulgent sidelong grin. “The best and last part is coming. Wait until it’s over and we’ll find your prince for you.”

Oriana quieted, chastised, but took her sister’s hand in hers as the ceremony began.

Venice’s Festa della Sensa, Marriage to the Sea, had been celebrated for almost six hundred years. What began as a commemoration of the Serenissima’s naval prowess was now a tradition on Ascension Day to pay tribute to the sea that held their land in its loving embrace, a ceremony that paid homage to the power, prestige, and prosperity each brought to the other and their interdependence.

All the members of the procession were aboard, the bells began to peal, a cannon exploded on shore, and the Bucintoro began to sail out into the glistening blue waters amidst the cheering. The burgundy and gold ducal galley, constructed in the renowned Arsenale, was a floating palace, rebuilt once every century. Its wood shimmered, polished to a glossy finish, its flags bright and flapping in the midday sun. Now and again, the golden trim sparkled as if kissed by the sun. The gilded mythological creatures rose in stark relief along the bright red sides of the long slim vessel. Forty-two crimson oars, each eleven meters long and manned by four arsenaloti—the craftsmen of the Arsenale, one of the greatest industrial complexes in the world—propelled the flagship, named for the ancient mythological word meaning “big centaur,” out toward the port.

The waters around them churned and a flotilla of boats of every shape and size, including the barge carrying the Fiolarios, whirled around the Bucintoro, worker bees buzzing around the queen. Eagerly they followed it out to the Porto di Lido, where the deeper waters of the Adriatic waited, where the tip of the long curved sandbar ended. As the large boat stilled, the Bishop of Castello, the religious official who had presided over the ceremony since its inception, stood beside the Doge on the bow. Below them, adorning the prow, was the gilded wooden sculpture representing Venice dressed as Justice, with both a sword and scales.

From the Fiolarios’ perch a few boats away, the distinct figures of the two men were visible, the short one in a black robe, purple sash, skull cap, and beard, and the taller one, with his gold, embroidered cape furling out in the wind and distinctive headdress upon his skull. Nevermore than when seen in profile did the ducal cap cast a unique silhouette; rising from the flat top front of the head, the back rising majestically to peak in a small horn shape, the elongated flaps extending down to cover the Doge’s ears.

Sophia and her family could see the Bishop raise his hands and form the sign of the cross, blessing the waters of the sea in peace and gratitude. His hand lowered, fumbled amidst the folds of his robes, and rose back up, the Blessed Ring now in his hands. As he turned to address the Doge, his words took wing on the wind. Mere mutated snippets of sound found the pilgrims on the shore, the melodious tones blending with the strains of madrigals performed by two groups of singers, one on each side of the towering columns. Every man, woman, and child in attendance knew the ancient words the Bishop intoned to Il Serenissima on behalf of his people.

“Receive this ring as a token of sovereignty over the sea that you and your successors will be everlasting.”

Doge Donato stepped forward, accepted the token, and bowed in thanks. Gesturing to the crowd on the banks of the water, he held it high and his archetypically dour countenance broke into a grin.

“We espouse thee, O Sea, as a sign of true and perpetual domination.” The Doge’s pledge carried across the blue and green waters to the boats and farther on, to the shore, and the sea of anxious captives.

With a short swing of his long arm, he hurled the ring into the sea. For a moment it glittered against the bright azure sky, a reflection of the golden sun as bright as a star in the black heavens. It arced and fell into the waiting sea, the splash small yet resounding, sealing the marriage. The crowd roared, erupting into cheering jubilation as the small piece of jewelry splashed into the waters, to sink forever into its depths.

The Fiolario family hugged and kissed each other and many of the crowd around them, strangers who were no longer unfamiliar as they shared this moment of renewal and blessing, cheering and crying as one. These Venetians, forced together by the physical confines of their land, were bonded spiritually, perhaps more than the inhabitants of any vast kingdom. The applause and adulation continued until La Maesta Nav, the ship of majesty, returned to shore, disposing of its passengers amidst the exultant crowd. Only when the Doge, the Bishop, the government officials, and honored guests passed through the throng, embracing and shaking hands, did the horde begin to disperse.

“Come.” Zeno gathered his women as they lit ashore and onto the piazzetta. “Now to enjoy ourselves.”

“It is so wonderful to see you, Signore Fiolario.” Doge Donato shook Zeno’s hand with both of his large paw-like ones, his strong voice almost inaudible over the cacophony around them; music of all types, from all corners of the square, mingled with thousands of voices, strange and familiar languages blending into one stream of human sound. Bowing over their hands, brushing a kiss on those of Marcella and Viviana, the imposing ruler acknowledged each of the Fiolario women one at a time.

It had been a day of wonder and delights, filled with all that the ostentatious celebration had to offer, the bountiful banquets, processions and performers, the jugglers, dancers, and acrobats. Oriana and Lia had glimpsed a prince or two, mooned over their handsome faces and opulent dress, but in the end, had been too shy to approach them. The sadness and turmoil of the past few days, though not forgotten, had been kept at bay like water behind a temporary dam, but the Doge’s presence had loosened the flood gates once more. The powerful leader would not have deigned to give a moment’s thought to a family such as theirs if Zeno were not a prestigious member of the Arte dei Vetrai.

Mother and grandmother gave small, respectful curtsies to the Doge and the group of powerful men behind him, Sophia and her sisters following suit. The small bevy of men offered bows and nods in return.

“It is a great day for all Venetians.” Zeno’s wide mouth curled up in a ghost of a smile. “A day of compassion and understanding for us all, is it not?”

Viviana tugged on her husband’s arm, a stiff smile crinkling her plump, flushed cheeks.

Doge Donato nodded and smiled, agreeing, showing no outward response to the bitter undertone of Zeno’s words.

“Sì, sì, certamente, of course. I hope you enjoy the rest of this wonderful day.”

He bowed and the Fiolarios, recognizing their dismissal, bowed or curtsied in reply, happy to return to the merriment.

The family withdrew, merging into the rambunctious crowd.

“Their displeasure is palpable, do you not think?” Donato asked of his obeisant entourage.

“The glassworkers are angrier than they have ever been,” an older man responded, stooped and gray, his bent body a shapeless form under his mantled black robe.

“All of them, Cesaro?” the Doge asked.

“For the most part, yes,” the statesman said with obvious hesitation. “There are a few who help us, who are as concerned as we that other lands will not develop the technique and take away some of their revenue, but they too grow leery of our methods.”

“If they unite, their power will grow,” said a simply robed, younger man, a member of the larger Maggior Consiglio. “We must pull the strings tighter.”

Doge Donato’s head spun to the fair-haired, fresh-faced man before him. “We are already a land divided by our difficulties with the Pope and the Empire. How many more confrontations can we balance at once?” Donato put his hands together, closing the long fingers, one upon the other. What looked like a clasp of prayer was, in truth, a gesture of impatience, an attempt to contain his growing frustrations. “What began with the sordidness of Saraceno, the Canon of Vicenza, now rages over two perverted clerics, but the essence of the dispute is the same. We must retain control of our citizens, clergy or not. We are Venetians first, Christians second.”

A short and husky man robed liked his colleagues, shifted his gaze between his leader and the retreating flock of Fiolarios. “The divisions are distinct—those who align themselves with you and Father Sarpi and those who pledge devotion to Rome through the Papal Nuncio. It is no longer a secret who among the senators is on which side. There are meetings every moment of every day. It is clear who is with whom and who receives the couriers from Rome.”

“Sì, Pasquale.” Donato nodded solemnly. “I am besieged with their admonitions myself, and now I am castigated over the senatorial decree forbidding all gifts and bequests to churches and monasteries.”

“They see the loss of taxes, nothing more.” The man attempted to calm and soothe the disturbed Donato.

Pasquale da Fuligna was no longer young but not yet old. He had been a part of the large Grand Council, comprised of every nobleman over the age of twenty-five, for eleven years. He had learned much in that time and his loyalty and devotion toward Doge Donato solidified in their like-minded beliefs. That Pasquale’s father, Eugenio, a council member for more than thirty years, hated the Doge and everything he stood for, added to Pasquale’s inducement to stand by Donato.