Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

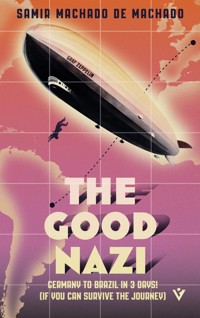

A zeppelin leaves Nazi Germany bound for Rio de Janeiro. For those on board it's a luxury holiday, until one of them is murdered.Police Detective Bruno Brückner, travelling on the airship, is immediately asked to investigate - and soon discovers that the murdered man was not the proud Nazi he claimed to be. What's more, he was carrying a stash of banned 'degenerate' material.As Brückner interviews his fellow passengers - a wealthy baroness, an antisemitic doctor, a debonair Englishman - his inquiries will uncover a startling story of fake identities, queer love and revenge, where nothing is as it appears, until finally the secret of the 'good Nazi' is revealed...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 153

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

2

3

4

5

Forget about what you are escaping from.Reserve your anxiety for what you are escaping to.

michael chabonThe Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

6

Diagram of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin and its gondola8

Contents

One

It emerged like a Valkyrie in the skies of Recife, advancing through the clouds with a serenity that concealed its rapid progress. Viewed head-on, it was just a silver disc, a shimmering shield. However, as it moved it was moulded by the light which struck its every surface, its graceful shape disguising the astonishing reality: at that very moment, sixty-seven tonnes were floating elegantly over the state of Pernambuco.

Three years earlier, its first passage through the city had been the occasion for a municipal holiday and had brought huge crowds onto the streets. But this was not the first of its many trips to Brazil, nor would it be the last. There were ten per year in total between the months of June and October, undertaken with German regularity, and there had never been any accidents. Although there were no longer any holidays or crowds, the airship still 10drew fascinated gazes, from people staring out of their windows, children on the street and anyone else whose routine was interrupted by the sight of that 230-metre colossus.

It was four in the afternoon when the ropes were tied to the mooring mast and the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin landed in Campo do Jiquiá, Recife. The first to board were the customs officers, the maritime police and the port health authorities, to carry out their inspection. Then the passengers disembarked. For some, it was their final destination. For others, taken by car to the Hotel Central, it was the last opportunity, after nearly three days spent crossing the Atlantic, to stretch their legs or smoke (which, naturally, was not permitted on board), before continuing their journey for a further day and a half to Rio de Janeiro.

Hotel Central was the tallest building in town, a yellow tower built in the style that had only recently come to be called art deco. Its seventh-floor restaurant provided a panoramic view over the city. A group of tables was reserved for the passengers of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, both those in transit and those still waiting to board.

Among them, seated alone at a table, was a man in a dark suit.

The passport in his breast pocket would have revealed the following details: Name: Bruno Brückner. Age: 11thirty-two. Build: medium. Face shape: oval. Eye colour: grey. Place of birth: Berlin. Occupation: Kriminalpolizei, police detective. A recent scar on the right side of his face, running from the temple to the middle of his cheek, lent a certain air of danger to his features, which, otherwise, gave off a neutral, distant look of indifference. The swastika pin attached to his suit showed affiliation to the party which was gradually permeating every aspect of German daily life.

Bruno was drinking his whisky and soda, reading a recent edition of Aurora Alemã (German Dawn), the Nazi party’s weekly magazine, published by the embassy in São Paulo. The news, several months out of date, reported how, after having gained a majority in the Reichstag and thus consecrating their leader as chancellor, the Nazis were now passing the Enabling Act, which gave absolute power to the Führer to create laws without being inconvenienced by parliament or the courts.

Bruno put the newspaper to one side. He took a brown paper envelope from his waistcoat pocket and, from inside it, removed a card his nephew had given him at the train station in Berlin before he departed for the LZ airfield in Friedrichshafen. In the child’s drawing, the airship was smiling like a big flying whale. Little Josef had drawn his uncle inside that whale, wearing a hat and with his hand raised in farewell, as if he were the proverbial biblical prophet.12

Bruno smiled, put the card back into the envelope, returned it to his pocket and picked up the newspaper again. The news was always delivered in the same tedious and optimistic tone of the party propaganda that was now the voice of a government which sought to fuse the party into the national identity: being German would necessarily come to mean being a Nazi. Faithful to its beliefs in German racial superiority, the newspaper adhered to its totalitarian motto: “Deutschland über alles. Germany above all… love it or leave it.”

Bruno grew tired of the newspaper and looked around the dining room, seeking to identify which of his travel companions from the days spent over the ocean would stay on as part of the group continuing to Rio. His discreet habits meant he had not interacted with them much. During the journey, he had chosen to rise early and have breakfast alone, before everyone else, and had spent most of his time reading, either in the dining room or in his cabin, which prevented others from striking up conversation with him. His gruff air was also justified by the lack of any sights to admire during the past few days: no matter which window you looked out of, all you could see was the tedious and endless Atlantic horizon. He had sought not to arouse the interest of any of the other passengers, who barely noticed him, or, if they did, took him for a shy recluse.13

There were some new faces among those present, but one seemed familiar. This man was of a similar age to him, with jet black hair that was combed back and set rigidly in place with gleaming Brilliantine. He was also sitting alone and, despite the heat, wore a black overcoat, as if he expected an improbable winter to arrive in the city at any moment. He was cradling a leather briefcase in his hands, protectively, and for an instant Bruno felt the other man was staring at him. He stared back at him and the man, out of instinct or politeness, looked away and went back to letting his gaze wander around the dining room, sombre and blasé as if in a Tamara de Lempicka painting.

Bruno did not remember having seen the man on board and thus assumed he was a guest at the hotel or a passenger waiting to be taken to the boarding gate. He finished his whisky and soda just seconds before a member of the hotel staff came to announce that the taxis that would take them back to the Zeppelin were waiting for them at the entrance. When he got up, he noticed the man with the briefcase had also risen and was heading to the lift with the others.

So, he was a passenger, Bruno concluded.

At half past six the sun went down and the taxis returned the passengers to Campo do Jiquiá. As they entered the Zeppelin, just as when they had boarded in 14Germany, each passenger was given a white linen napkin inside a personalized envelope, which each one of them had to keep and reuse until the end of the journey, apparently to reduce the weight on board. Bruno could not see what difference half a dozen napkins would make to the tonnage of that Leviathan and suspected that this was done to compensate for the lack of laundry facilities.

As soon as he entered his cabin, Bruno saw that another whisky and soda was waiting for him on the table by the window. It was one of those little details which had garnered such high praise for the service. Next to the drink was a typed list with the names of all the passengers on board. He noticed a greater number of Brazilian names, passengers with surnames like Botelho, Tavares, Correia, almost always men and almost all with the same occupation: commerce.

It was understandable. Just to go on that journey of a day and a half between Recife and Rio, sailing through the air, feeling like a character in a Jules Verne novel, would cost you 1,400 reichsmarks. The trip was a small extravagance these men had permitted themselves and, in some cases, their wives.

Likewise, Bruno had indulged himself. He could have come to Brazil by ship, it would certainly have been cheaper, but he did not like the idea of spending two weeks bobbing up and down on the high seas. And as 15there were no transatlantic passenger aircraft, the only other possible way for a passenger to cross the Atlantic from Europe to South America was to travel through the air on the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin.

When he looked at the list, he also noticed that a single new German name had appeared since their departure from Friedrichshafen: Otto Klein. This, he concluded, was the name of the fellow from the hotel.

Bruno sat down on the sofa, drank his whisky and soda and contemplated the turf on the airfield. The truth was, there wasn’t much to do on board except eat, sleep and socialize—the passenger gondola was not much bigger than a luxury train wagon. In the prow were situated the command deck, the navigation room, the radio room and the tiny galley for food preparation—which boasted of being the world’s first to be made of aluminium. And on either side of a narrow corridor running through the stern was a row of small but comfortable cabins. At the end of the corridor were the WCs and washrooms.

At eight o’clock in the evening, once the postbags had been delivered and collected and the sixteen enormous gasbags had been refilled with hydrogen, the ropes were cut and the Zeppelin departed. Soon after it had taken flight, the chief steward knocked on the door of each cabin, informing the passengers that dinner would be served shortly.16

Bruno pulled his suitcase over and unpacked his things before leaving the cabin, whose sofa would be dismantled by the room attendant and made up as a bed. He made his way to the dining room which dominated the centre of the Zeppelin’s gondola. After examining each one of the passengers in turn, Bruno sat at an empty table—the one nearest to the prow, next to the starboard windows.

The wooden chairs were upholstered with elegant floral prints, the tables draped with fine linen tablecloths, the wallpaper decorated with art nouveau arabesques and the windows framed by curtains. The place gave off a pleasantly nostalgic feeling as if, while on board, one could return to the world as it was before the Great War.

But a return to that world of abundant luxuries and comforts would also inevitably mean a return to imminent war, for that had been the natural consequence of those times. He had been twelve when the war began and sixteen when it ended. That had been his adolescence. And who in the world, thought Bruno, having reached adulthood, would really want to relive such an adolescence?

Two

Faithful to the nationalist spirit of the time, the gastronomic experience offered by Zeppelin on board its airships was not the best of global cuisine, but rather the best of German cuisine, which, we can safely say, no one ever accused of being light and refined, but to which all due respect must be given for having provoked in its people a persistent questioning of the meaning of existence, aiding the formation of many generations of great philosophers. Over the course of the journey, however, some concessions had to be made to local cuisines as they restocked at each stop, guaranteeing some variety at the dining table.

Bruno picked up from the table that evening’s menu typed out in German and Portuguese and printed on card with the LZ letterhead:18

Auf See zwischen Pernambuco/

Rio de Janeiro 16/10/1933

At sea between Pernambuco and

Rio de Janeiro 16/10/1933

Abendessen

Tapiokasuppe

Kalbfleisch in Sahnesauce mit Spaghetti

Geröstete Pfifferlinge

Salat aux fines herbes

Verschiedene Käsesorten

Nachtisch

Vanille Eiscreme

Dinner

Tapioca soup

Veal in cream sauce with spaghetti

Roasted chanterelles

Salade aux fines herbes

Selection of cheeses

Dessert

Vanilla ice cream

Bruno ordered an orangeade to go with his meal.

Then he waited. The table he had chosen had room for five: three chairs and a two-person banquette were arranged around it. Since he was feeling expansive that evening, he had sat on the banquette to get a good view of the people entering the dining room from the cabins.

As more passengers came in, it wasn’t long before the empty chairs at his table were filled. They were all people 19with whom Bruno had conversed only in passing over the previous two days.

The first to take a seat was Baroness Fridegunde van Hattem. Although her age was a state secret, a glance at her passport would have revealed that she was fifty-four years old. Build: medium. Face shape: oval. Eye colour: blue. Place of birth: Vienna. Occupation: Hausund Familienarbeit, though she had never carried out any of the domestic duties of a housewife—she relied on the help of countless servants, all of whom had been left behind in her mansion.

The baroness had the strong, domineering personality of someone who, having been born into a good family, and having frequented high society since childhood and married well, expected to have her every whim satisfied. Her voice was slightly husky, almost masculine, the result of the many cigarettes she was in the habit of smoking in long cigarette holders and which, much to her displeasure, she had abstained from while on board the airship. It was her custom, or at least this is what she had told Bruno, to travel every year to escape the European winter, staying for long spells at the Copacabana Palace.

‘I haven’t seen winter for five years,’ she said.

The second person to sit down was Dr Karl Kass Voegler. His passport gave his age as forty-five. Build: slender. Face shape: triangular. Eye colour: blue. Place of 20birth: Düsseldorf. Occupation: Sanitätsarzt, public health physician. His forehead was immense, an impression reinforced by his hair loss, which had left hair only on his temples. He sported the narrow ‘toothbrush’ moustache, trimmed at the edges, that was popular from north to south across the globe, stamped upon the lips of everyone from Chancellor Hitler to the Brazilian writer Monteiro Lobato, and, of course, Charlie Chaplin.

He somewhat resembled an actor in an expressionist film, with his fair, almost pale skin that would not fare well in the heat and Brazilian sun. His hands, with their long fingers and knobbly joints, moved across the table like a pair of trained albino spiders that scuttled to fetch him a piece of cutlery, a glass, his napkin, before dying with their legs seized up as his fist closed over the item in question.

The doctor had the hearty manner of a rousing public speaker and was travelling at the invitation of the German embassy in Brazil to take part in the Brazilian Eugenics Congress, where he was to give a lecture to the São Paulo Eugenics Society about the dangers of racial mixing to a nation’s health.

‘I didn’t think that a country like Brazil would be so interested in the topic,’ Bruno said. ‘But I must confess, I know very little of her people.’21

‘The country is modernizing!’ Baroness van Hattem said. ‘Rio de Janeiro is beautiful! And they’re most interested in questions of hygiene. Naturally, with the number of half-breeds there… That’s why they have done so much to encourage European immigration, especially from Germany.’

‘Yes, it’s imperative that the nation’s blood be whitened,’ Dr Voegler agreed. ‘That is precisely the topic I intend to expound to my Brazilian colleagues. They believe that by prohibiting the arrival of Asian and African immigrants, and encouraging that of Italians and Germans, the superiority of white over negroid blood will be sufficient to whiten the race.’

‘But it isn’t?’ the baroness asked.

‘No, of course it isn’t,’ Dr Voegler said. ‘It’s also necessary to promote eugenic awareness among young people. They must be encouraged, for example, not to marry members of inferior races and social classes, so that the pure races have more children than the degenerate ones, thus avoiding the proliferation of half-breeds.’

Chief Steward Kubis came to the table and the two ordered their drinks. The baroness asked for a gin and tonic, Dr Voegler just water.

‘Of course, one must also sterilize the undesirables,’ Dr Voegler continued. ‘That was what I said in my correspondence with Dr Renato Kehl. The Brazilians are 22extremely enthusiastic about our work. I hear that a proposal is underway to insert an article into the new constitution making it the state’s obligation to “encourage eugenic education”. That is, if it hasn’t already been done. I don’t follow Brazilian politics.’

‘And how exactly does one encourage that?’ asked Bruno, more out of politeness than interest, since his attention had been captured by someone asking if the remaining chair was free. ‘Of course, make yourself comfortable,’ he urged the newcomer.

‘By sponsoring beauty contests, for example,’ Dr Voegler explained, immediately turning to the new arrival.

The young man who had sat down between them was blessed with an athletic build and Apollonian beauty, the kind only found in fashion shoots and on nationalist posters. He demanded attention, and he seemed to know it.

‘Dr Voegler, baroness. What a pleasant evening, isn’t it just?’ he remarked, taking his seat. ‘Why, sir, we have not yet been introduced. Charmed, I’m sure. I’m Mr Hay. William Hay. But you can call me Willy.’

A peek at his passport would have revealed his age to be twenty-seven. Build: slender. Face shape: square. Eye colour: brown. Place of birth: London. Occupation: (blank). He had the bold, louche gaze of a silent film lead and, as they would soon discover, the irony-laden, sharp 23