2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

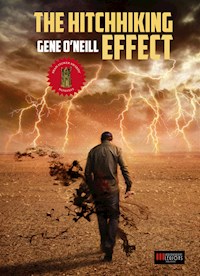

- Herausgeber: Independent Legions Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A new retrospective collection by the Bram Stoker Award Winner Gene O’Neill, containing some of his best known fiction: seven short stories, one new novelette, and two novellas, from which four Bram Stoker Awards finalists: 'The Burden of Indigo', 'Graffiti Sonata', 'Balance', 'Dance of the Blue Lady', 'The Confessions of St. Zach', 'Tight Partners', ‘The Hungry Skull’, ‘Rusting Chickens’, ‘Ridin The Dawg’ and ‘Firebug’, which was written as a endnote for this retrospective.

Also included an introduction by the Author. Cover Art by Vincent Chong.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Gene O’Neill – The Hitchhiking Effect

ISBN: 978-88-99569-05-1

Copyright (Edition) ©2016 Independent Legions Publishing

Copyright (Text) ©Gene O’Neill

1° edition epub/mobipocket: 1.0 March 2016

Proofreading by Jodi Renée Lester

Digital Layout: Lukha B. Kremo - [email protected]

Cover Art by Vincent Chong

Gene O’Neill

The Hitchhiking Effect

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Burden of Indigo

(appeared in the October 1981 issue of The Twilight Zone Magazine)

Graffiti Sonata

(appeared in the winter/spring 2011 issue of Dark DiscoveriesMagazine)

Balance

(appeared in issue 55, 2006, of Cemetery Dance Magazine)

Dance of the Blue Lady

(appeared in issue 53, 2005, of Cemetery Dance Magazine)

The Confessions of St. Zach

(published as a signed and lettered trade paperback in 2008 by Bad Moon Books)

Tight Partners

(published in 2013 by Written Backwards Press in Chiral Mad 3)

The Hungry Skull

(appeared in the spring/summer issue 2012 of Nameless Magazine)

Rusting Chickens

(published as a signed and lettered trade paperback in 2011 by Dark Regions Press)

Riding the Dawg

(published in 2014 by Thunderstorm Books in Mio Mojo)

Firebug

(a novelette original to this collection)

On the Right Side of the Road

(appeared in the Summer 2014 issue of Dark Discoveries Magazine.)

Transformations at the Inn of the Golden Pheasant

(published in 2014 by Cycatrix Press in A Darke Phantastique)

“Graffiti Sonata,” “Balance,” “The Confessions of St. Zach,” and “Rusting Chickens”

INTRODUCTION

by the author

In the summer of 1979 I spent six weeks at Clarion, which at that time was located at Michigan State University in East Lansing. It was one of the most intense six weeks in my life (almost comparable to the first part of Marine Corps boot camp).

It was the first time I’d been away from my young family for any extended period of time. It was my first time meeting a professional writer. It was the first time reading any unpublished writing other than my own. It was the first time anyone had ever critiqued my writing. It was the first time that I’d heard the term “plot skeleton.” So I soaked up everything, learned so many things about writing and the life of a writer… Perhaps the most important thing I learned was how to read my own material with a critical, objective eye; and then to make the necessary cuts, additions, and revisions, after going over the writing again and again and again. (What Hemingway called exercising the BS Detector.)

At the end of Clarion I was not in the top of my group of eighteen colleagues in terms of skill and writer development. But I must have demonstrated a spark of talent, because Damon Knight and Kate Wilhelm invited me to attend the monthly gatherings of writers at their home in Eugene, Oregon. I lived in Northern California, about an eight-hour drive away, but I was highly motivated to take advantage of the opportunity to learn more. They suggested I might get along with a young writer, Stan Robinson, who lived near me in Davis, California. Stan and I would make the trip up to Eugene eight or nine times during 1980. And as Damon and Kate suspected, the two of us got along fabulously. We became good friends.

Our routine: I’d drive over to Davis around 5:30 on Saturday morning, pick up Stan, and then we would power up to Eugene and arrive in the early afternoon, just in time to hunker down and read all the manuscripts that were scheduled to be critiqued that night.

I learned a lot during those weekends in Eugene—perhaps as much on those eight or nine marathon trips during 1980 as I learned full time at Clarion. We met a number of amazing young writers in Oregon, some who would soon become very well-known—John Shirley, William Gibson, Lucius Shepherd, Vonda McIntire, Steve Perry, Mark Laidlaw, and several others. Somewhere early on, maybe the fifth or so trip up, I took along a new short story entitled “The Burden of Indigo.” I knew it must be good because Stan broke the rule that we never talked in the car about material we were taking up for the Clarion-style group critique. He said some very enthusiastic, nice things. As did most of the others in Eugene—a rare thing, as the group was usually a very harsh critic of stuff.

But Damon brought me back to earth with his sarcastic take on a critical scene in the story—he said the description of a young boy sitting by a pond reminded him of a cherub on a religious postcard. I transferred his criticism literally and incorporated it directly into the short story—the main character thinks the boy looks like “a cherub on a postcard.” In the kitchen later that night I knew I had made an important step as a writer—that moment when you know you have crossed over from being a typist to being a writer. Kate said to me in the kitchen after the critique, “I knew that you had something to say.” That was all she said, but it was enough.

I was to learn as much from Stan Robinson during the eight hours in the car up and the eight hours back—we rapped on all the time (at that time we likened ourselves to the Beats making one of their marathon trips). Stan was formally educated—an English/writing major. He would soon go down to UC San Diego and finish his Ph.D. And although we would often communicate, I lost my only first reader. On those long trips, he passed on a ton of the formal writing tips/theory that I’d missed by not formally studying English, literature, or writing in college. And I would arrive back home exhausted, but immediately jot down what I’d been exposed to both in Eugene and by Stan during the weekend. (For example, I’d never heard the term and importance of a story’s premise. I also heard Stan’s theory that an expository lump was just fine…if it was interesting—a contrast to what I’d been told at Clarion. We talked of future projects, and I heard the complete outline for the Mars Trilogy years before it was written.)

Information in the car didn’t travel only one way, though. I’d had a pretty well-rounded street education by then, beginning from when I was growing up in a working-class ghetto near a shipyard—boxing and playing other sports—to holding a number of blue-collar jobs, serving in the Marines overseas, working my way slowly through a small state college in Sacramento, and eventually teaching Adaptive P.E.

Stan, to his credit, took note of much of that colorful street stuff, even including relevant bits in his own writing. When he won his first Nebula for his novella The Blind Geometer, he mentioned one of his characters was informed by a real-life P.E. teacher, who had provided a great role model.

So the trips up and back were a major learning experience and influence on my development as a writer. But something I heard in passing in Eugene I stored away, and it would eventually inform the quality of my writing in a major way.

Kate Wilhelm, during one of those weekends, had briefly suggested in conversation that she thought all writing, including one’s fiction, was autobiographical in some way. At the time I completely dismissed that idea. After all, at the time, I was writing and would soon publish mostly a kind of hybrid science fiction—with other worlds, aliens, and some of the other tropes of SF. To me this material obviously wasn’t autobiographical.

It’s interesting how things stick in the back of your mind for years.

As time passed, my writing gradually matured, and I became more solidly a mixed-genre writer, even occasionally turning out a mainstream piece of fiction (this was hard to sell at the time—another story). But at some point, I began to wonder if Kate’s suggestion might not be actually profound. After due consideration, I had to admit that an important component in each of my best stories was the right-on, emotional reactions of the characters, and I realized that the reliability and validity of those emotional reactions came from a life-long experiment involving only one Subject—the experimental S was me, of course. So I carefully read back over all my previous published work, even the more-or-less early SF, and I eventually realized that Kate was probably correct. I found large pieces of myself in almost every story, often in the emotional reactions of the main characters—both male and female, gay and straight, good guy and bad guy, whomever. At some point in each piece of that early work—sometimes in several places—I found a direct parallel with my own life experiences.

For example, my first professional sale was to the Twilight Zone Magazine, a mixed-genre story, “The Burden of Indigo.” Readers have commented on realistically sharing the feelings of the Indigo Man, his lonely sense of isolation and being ostracized by both Shield residents and Freemen. When I was seven, I had polio and spent nine months partially paralyzed in a bed at San Francisco Children’s Hospital. After making an amazing full recovery, I returned to my grandparents’ home near the naval shipyard. At that time people were frightened by a lack of understanding of polio—much like the early fear of AIDS. The working class in my neighborhood thought it was an indication of being dirty and not sanitary, being low-class. I was mostly ostracized and left alone, except when I had to defend myself from being tormented and attacked on the way home after school.

Ironically, at this time the doctors recommended to my grams that I spend my afternoons lying down and resting in my bedroom for at least an hour. I hated this restriction and, of course, never slept. Instead, I made up stories about the shadows flickering on my bedroom walls when the venetian blinds were partially closed. (Damon said that all writers were little green frogs sometime in their life history, and I was, during that time.) Later on, perhaps as a reaction to this rough-and-tumble early time, I developed a strong interest and more than just a little expertise in contact sports like football, basketball, and boxing. Even now the memory of those lonely times back when I was eight or nine still causes an emotional reaction (I feel for that little boy).

Okay, what did I do with this discovery about my own writing? Throughout the last twenty or so years, I’ve made a conscious effort to capitalize on this observation.

Whenever appropriate during the story development, I insert some true-life event/character, trying to capture my own emotional response in words and transfer them to the page. If I’ve selected the correct words and efficiently completed the transfer to the page, the reader should experience the emotional content of the scene. Of course, usually I’m only partially successful, but the piece may still turn out to be pretty good. Sometimes I’m not talented enough to encapsulate any of the real poignancy I feel into words (romantic material perhaps becoming too sentimental). Or maybe something that caused a deep impact in my real life didn’t always translate too well, didn’t emotionally move the reader despite my writing ability (a harsh observation from the ghetto, or something in the boxing ring, or from my Marine experience—the violence perhaps not believable or too shocking, masking whatever intimacy I hoped to share).

As one might expect, I often had to disguise the real-life event. Damon used to say “You will never be a very good writer until you can strip naked and pirouette in front of your audience.” I take this to mean the very good writer takes chances, no flinching. Or something similar to what Hemingway meant when he said “The good writer, like the good bullfighter, fights in the terrain of the bullfighter; but the great writer, like the great bullfighter, fights in the terrain of the bull.” I’ve reached the point in my writing life where I have no problem figuratively shucking off my clothes and dancing—I don’t worry about reader judgments of my personal preferences/behaviors they assume from my writing. But I can’t, in good conscience, strip away all the clothes of a relative, colleague, or friend. So the actual scene transferred may itself sometimes be a kind of fiction, but its structure true nonetheless.

Those parts of my writing where the reader is able to pick up on the emotional transference and be truly moved are often recognized as my better work. And I would usually agree with the assessment.

I call what I attempt to do the hitchhiking effect—transferring the emotional load of an autobiographical experience from my own background directly into my fiction writing for the reader to hitchhike on. This seems to work well for me.

Nowadays I would fully agree with Kate Wilhelm that my fiction is indeed autobiographical.

THE BURDEN OF INDIGO

The road was a relic of the past: a six-lane highway complete with a wide, planted median. Overgrown, most of the plantings had died; only a few stubborn oleanders survived, battling the weeds, crabgrass, and summer drought. The lane-divider stripes had faded to a dull gray, and, poking through cracks in the asphalt, bunches of golden field grass decorated the pavement.

Bypassing the village, the highway stretched to the western horizon, separating fields of yellow hay, cutting between rolling hills dotted with black oak. Framed by the orange-pink sky, a dark figure walked beside the median. It was a man. He was burdened with a backpack and was ambling in the energy-conserving gait of an experienced wanderer.

Nearing the outskirts of the village, the man stopped. Shading his eyes, he glanced back, watching the sun disappear; then he turned and walked across the three lanes. He stopped on the shoulder of the road, looking down the main street—the only real street—of the village.

His shoulders were rounded and slumped as if he carried a much heavier load than a backpack. He grasped a carved and polished walking stick, his only adornment—except for his color. Clothes, backpack, hair, beard, all exposed skin: from head to foot, the man was the color of dark blue ink. Indigo.

The indigo man saw no one on the village street, not even a dog; suppertime.

Cautiously he walked into the village, inspecting the buildings as he moved down the center of the street. His search was specific, not the unmotivated curiosity of an idler. Above the general store a faded sign read Enjoy Coca-Cola. He’d seen the red-and-white signs in many villages, advertising a beverage that was no longer made. On both sides of the street, the houses were identical boxes peeling a grayish paint. He stepped around the hummer pad at the center of the town. The circular disc of concrete with steps, ramps, and railings was well maintained, at odds with the general appearance of other structures.

Continuing down the street, the indigo man passed a school, the post office, a few more houses, and finally paused at the edge of town before a small, dirty building. Yes, there was the sign over the door, dusty but legible: C.P. Hostel.

Sighing, the indigo man stepped up to the heavy oaken door. He placed the palm of his hand against a metallic sensor inset in the door and waited, knowing that somewhere a computer recorded his identity and noted his location.

A whirr and a click. The door swung in.

Taking one tentative step inside, the indigo man looked about the large single room. It looked and smelled like a barracks: neat and clean. At the far end, arranged in a row across the hall, were five old-style military bunks, all made up, with hospital folds. Behind the bunks were two doors labelled M and W. Immediately in front of him was a heavy wooden dining table with ten chairs of matching black oak. To his right was a recreation area: a card table with several open books and a half circle of folding chairs, ringing a blank holoview bowl.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!