5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Magical Cambridge

- Sprache: Englisch

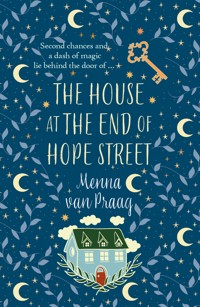

Second chances and a dash of magic . In Alba Ashby's hour of need, she finds herself on the doorstep of number 11 Hope Street, a house that has stood quietly in Cambridge for nearly two hundred years. But this is no ordinary house. Its walls are steeped in the wisdom of past residents including Virginia Woolf, Dorothy Parker and Agatha Christie. Alba accepts an invitation to stay under the condition she has ninety-nine nights, and no more, to turn her life around. Guided by the energy of the house, where portraits come alive, bookcases refill themselves and hot chocolate has healing properties, the enchanting experience Alba and her new friends share will transform their lives in unexpected ways. WHAT READERS ARE SAYING: 'From the very first paragraph I was hooked . it's warm and inspiring, thoughtful, wise and if you're needing a little hope in your life just now, please do yourself a massive favour and read this book, with a mug of creamy hot chocolate and ginger snap biscuits! . the words take you all the way to Hope Street, where I think I will stay for a very long time!' Reader Review 'This is, truly, one of the very best books I have ever read. I gobbled it up in a matter of days and was so impressed by the empathy, kindness and wonder with which each and every character was treated.' Reader Review 'Oh I so didn't want this book to end, it was truly delicious!' Reader Review 'I rarely leave a 5* review unless I've really loved a book but this was one of those! It's the story of... well... a house, at the end of Hope Street, and its occupants all of whom are, or have been, in need of its magic. I usually avoid 'magic' stories like the plague but something drew me to this one... and I'm very glad about it.' Reader Review 'Beautifully written with life lessons for everyone, threaded through with a sprinkle of magic!' Reader Review 'I absolutely LOVED this, I couldn't put it down, and it's a while since a book has had that effect. A good story line and pace, which doesn't give too much away and builds nicely . I totally loved the way real life, historical people had stayed at the house.' Reader Review 'It's a sweet story, written with a deft hand and I enjoyed the twists and the development of the characters. To the author: good job and thank you!.' Reader Review 'What a lovely, gentle, original and inspiring book. If you've ever loved the wrong person . or you can't see your way ahead . or if you have a dream that you are too scared to follow, if you love literature or music, or cats or chocolate or mystery . then read this book.' Reader Review 'From the outset, the language and imagery are enchanting, and once you enter the House, you simply must uncover the stories and secrets within . There is great sadness but, thanks to Peggy and Stella, great hope too. One to read and read again I think.' Reader Review 'This is the first book in a long time that I have read in just one day. I could not put it down.' Reader Review

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 441

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The House at the End of Hope Street

MENNAVAN PRAAG

For my father, to whom I owe everything!

Contents

Chapter One

The house has stood at the end of Hope Street for nearly two hundred years. It’s larger than all the others, with turrets and chimneys rising high into the sky. The front garden grows wild, the long grasses scattered with cowslips, reaching toward the low-hanging leaves of the willow trees. At night the house looks like a Victorian orphanage housing a hundred despairing souls, but when the clouds part and it is lit by moonlight, the house appears enchanted. As if Rapunzel lives in the tower and a hundred Sleeping Beauties lie in the beds.

The house is built in red brick, the colour of rust, and of Alba Ashby’s coat – a rare splash of brightness in a wardrobe of black. Alba doesn’t know what she’s doing, standing on the doorstep, staring at the number eleven nailed to the silver door. She’s lived in Cambridge for four of her nineteen years, but has never been down this street before. And there is no reason for her to be here now, except that she has nowhere else to go.

In the silence Alba’s thoughts, the ones she’s been trying to escape on her midnight walks through town, begin to circle, gathering, ready to whip themselves into a hurricane. How did this happen? How could this happen to me? She’s always been so careful, never inviting any drama or disaster, living like a very sensible seventy-nine-year-old: in a tiny box with a tight lid.

And while most people wouldn’t achieve much under such strict limitations, Alba achieved more than most: five A-levels at fifteen, a place at King’s College, Cambridge, to read Modern History, and full PhD funding at eighteen. All this by virtue of two extraordinary traits: her intelligence and her sight. At age four and a half, as well as being able to name and date all the kings and queens of England, Alba started to realise she could see things other people couldn’t: the ghost of her grandma at the breakfast table, the paw prints of long-disappeared cats in the grass, the aura of her mother moments before she entered a room. Alba could see smells drifting toward her before she smelt them and sounds vibrating in the air minutes before she heard them. So, because Alba knew things other people didn’t, they never noticed she lived her life in a box.

But ever since the worst event of Alba’s life, she’s barely been able to see anything at all, constantly tripping over pavement edges, falling down steps, and walking into walls. She still hasn’t cried because to stay in shock feels safer, it keeps a distance between her and the thing she’s trying to pretend hasn’t happened. The numbness surrounds her, a buffer against the outside world, through which Alba can hardly breathe or see.

Today is the first of May, just after midnight. The moon is full and bright. Vines of wisteria and jasmine twist together across the red bricks, their flowers hanging over the windows and above the door. Their scent puffs through the air and, though she’s sorry she can’t see their colours, the smell begins to fill Alba with a sense of calm she’s never felt before. Her shoulders soften as she reaches up to touch the flowers hanging in wispy bunches above her head. Soon she’ll feel strong enough to walk again. But then she remembers, she no longer has anywhere to go.

In the silence Alba hears a low hum in the air, almost indistinguishable from the breeze. Still cupping the flowers in her palm, she listens. The hum grows louder and becomes a tune, the notes drifting toward her, and suddenly Alba is captivated. She knows the words to this song:

Sleep, sleep my sweet

Sleep and dream of butterflies …

The next line slips away as Alba thinks of the summer her mother sang that song, when she was eight years old, just before her father left. The tune grows louder, seeping through Alba’s skin, sending shivers down her spine. She knows she should be scared, but she’s not; she’s captivated.

Alba steps back to look up at the house, at its rows of dark windows, the panes of glass glinting. For a second Alba thinks she sees a face, a flash of white and blonde that disappears so the night is mirrored back at her. She notices a plant with flowers so purple they’re almost black. Its strangeness beckons Alba to come closer, rub its leaves, smell its flowers, slide her fingers into the earth … The charms of the house and its garden sink deeper into Alba and, without realising what she’s doing, she steps forward and rings the bell.

As Peggy Abbot scurries down the steps, pulling on her patchwork dressing gown, a picture of Alba starts to take shape in her mind: tiny and built like a boy, spiky black hair, intense blue eyes, a mouth that rarely smiles, a weight of sadness and self-doubt heavier than Peggy has ever felt before, but a sense of sight stronger even than her own. Suddenly she knows that this might be a dangerous thing indeed. The midnight glory is in bloom tonight. If Alba looks for too long she might see what makes its petals glow and, worst of all, sense what’s buried beneath it.

Wishing she were forty years younger, Peggy hurries along the hallway, slipping on the wood in her woollen socks.

When the door swings open, Alba steps back in shock, staring into the face of the oldest and most beautiful woman she’s ever seen.

The moment Alba steps into the house, she knows it’s different from any home she’s ever known. It is, quite clearly, alive. The walls breathe, gently rising and falling beside Alba as she follows the old woman down the hall. The stripped oak floorboards soften under her feet in welcome, the light bulbs and lampshades pull at the ceiling to get a closer look.

As she walks Alba gazes at the walls, weighted down by hundreds of framed photographs: black-and-white pictures of different women, in group shots and singles, wearing trouser suits and top hats, flapper dresses and flat caps, ribbons and pearls. Among the photographs are pictures, pencil drawings and silhouettes, and a few miniature oil paintings of powder-puffed female faces with curls piled high on their heads.

‘Wait.’ Alba almost stumbles into the wall. ‘That’s Florence Nightingale.’

‘Oh yes,’ Peggy says. ‘She stayed with us for a spell before she went off to the Crimea. When my great-, great-, great-aunt Grace Abbot ran the house. A lovely girl by all accounts, Flo, though rather strong willed and a little too fond of sailors …’ Peggy smiles.

‘Gosh, really?’ Alba whispers. ‘That’s … gosh.’

As Peggy ushers her into the kitchen Alba feels a flash of fear. She ought to think twice before entering the homes of complete strangers. Hidden under the folds of Peggy’s patchwork dressing gown could beat the heart of an evil witch who sees Alba as a modern-day Gretel. But when Alba enters the kitchen she’s enveloped in the scent of something magical: cinnamon, ginger, lavender and several spices she can’t possibly name, and her fears evaporate. She feels three years old again, transported to a wished-for childhood of baking biscuits with her mother on Sunday afternoons. If Peggy is bewitching her, then the spell is complete.

A few minutes later Alba sits at one end of a long oak table, watching Peggy search for a saucepan. The old woman is bent over, clattering around in the wooden cupboards, muttering swear words as she flings unwanted pans aside. Alba begins to wonder just how old Peggy is. With her white hair and papery skin, slight stoop and frail limbs, she might be anything from seventy to a hundred and seven. But her movements are quick and light and her voice doesn’t carry any quiver or depth from age.

Peggy stands, brandishing a saucepan. ‘Do you like hot chocolate, dear?’ she asks. ‘I don’t think tea will do, we need something more fortifying on such an auspicious occasion. Hot chocolate with fresh cream, that’s the thing.’

Alba nods, still captivated by the kitchen’s smells, still shocked by the turn her night has taken, not really registering Peggy’s words. While the old woman pours a pint of milk into the saucepan, Alba glances around the kitchen. It’s vast, the length of a long garden, with creamy yellow walls that reach up to meet black oak beams running across the arched ceiling. As in the hall, every inch of the kitchen is covered with rows and rows of photographs. Alba gazes at them, wondering who they are and why they are decorating the old woman’s walls.

‘They’ve all lived here, at one time or another.’ Still stirring the milk at the stove, Peggy speaks without turning around. ‘They came to the house, just like you, when they’d run out of hope.’

Alba frowns at the back of Peggy’s patchwork dressing gown, at the wild white hair reaching down to her waist, wondering how on the old woman knew what she was thinking.

‘They left to lead wonderful lives or, in some cases, afterlives.’ Peggy chuckles. ‘The old residents can inspire you, if you let them. One in particular, actually.’

‘Oh?’ Alba asks, only half listening. In a frame just above the kitchen sink she sees an oil painting of a woman with blonde hair twisted into knots at the sides of her head. Alba squints for a better look. ‘But, that’s—’

‘Yes.’ Peggy doesn’t turn to look. ‘She stayed here in 1859, suffering from a severe bout of writer’s block. She started writing Middlemarch in this very kitchen.’

‘No,’ Alba gasps, ‘really?’

‘Oh yes. Half the history of England would be quite different if this house had never been built, believe me.’

And although she can’t explain why, Alba does. She already feels closer to this woman than to her own family. Peggy stops stirring, steps over to the fridge, tugs open the door, sticks her head inside and takes out a china bowl. ‘This cream is the real stuff,’ she says, and smiles. ‘I whipped it up myself. I can’t countenance that synthetic crap one squirts from a bottle, can you?’

‘No.’ Alba agrees, amused to hear such a sweet old lady swear.

‘I’m glad to hear it.’ Peggy sets the bowl down on the marble counter next to the stove. ‘I can’t trust anyone who won’t take real cream, or real sugar. Those’ – Peggy searches for the word and shudders – ‘sweeteners, such a seemingly sweet, really are beyond the pale, don’t you think?’

Alba watches Peggy stirring cocoa into the milk. Suddenly she never wants to leave. She wants to sit in this kitchen, surrounded by the smell of spices, forever. Alba slips off her coat. ‘Why did you invite me in?’ she asks. ‘It was very kind, but I don’t see …’

‘You don’t?’ Peggy smiles. ‘Because I think you see an awful lot more than most people.’ She sets two giant mugs down on the table. ‘Don’t you?’

‘Thank you.’ Alba glances at her cup. It’s the first time in her life that anyone has ever guessed who she is and what she can do. ‘Yes,’ she admits softly, ‘I suppose so, though not since …’

Peggy takes a sip of hot chocolate. ‘Since what, my dear?’

Alba looks up. How can she possibly explain the devastating events of the last few days? Her head is so full of fury, her heart so steeped in sadness, that she can hardly make sense of anything anymore. All Alba knows is that she wants to undo time, run backward through the last seven months, unravel everything and begin again: finish her MPhil, write a groundbreaking thesis, publish papers, until she’s at the forefront of the next generation of great historical minds. And if she can’t achieve that, something truly brilliant, then what’s the point in living at all? Because in her family, being mediocre, ordinary, run-of-the-mill, simply isn’t allowed.

As though Alba had just spoken her thoughts aloud, Peggy smiles sympathetically. ‘You know, in my long and extensive experience, what we want isn’t always what will make us happiest,’ she says. ‘But we’ll come back to that. First, tell me what brought you to my doorstep. Start from the beginning, and don’t leave anything out.’ Peggy sits back in her chair, smoothing her patchwork dressing gown across her lap, hugging her mug of hot chocolate to her chest. This is her favourite part. After more than a thousand stories in sixty-one years, she never fails to get excited at the prospect of a new one.

‘Well …’ Alba stalls. ‘I don’t … I mean, I was just walking around town, not going anywhere, and then … and then I just found myself here.’ Nervous, she scratches the back of her neck, tugging at short spikes of black hair, hoping she doesn’t look as messy as usual, then realising she probably looks even worse. ‘I didn’t mean to knock on your door, it just sort of … happened.’

‘Take a sip of chocolate,’ Peggy suggests. ‘It’ll help to clear your head.’

As the warmth slips down her throat and into her belly, Alba starts to feel soft and snug, as if the kitchen has just hugged her. And, after a few minutes she isn’t scared to tell the truth any more. At least a little bit of the truth. But, where should she begin? History. Love. Trust. Betrayal. Heartbreak. Alba shifts the words around in her head, wondering what to hide and what to reveal.

By the time the last of the hot chocolate has gone, Alba has told Peggy about failing her MPhil and ending her career. However, she has carefully, deliberately omitted the single most important piece of information, the thing that slots it all together.

‘I can’t stay in college any longer, and I can’t go home,’ Alba says, though she stops short of explaining why. ‘So I was wandering the streets in the middle of the night.’

In the ensuing silence, the spices circle the kitchen, even stronger than before, and although Alba can’t see the smells, she can hear the hum of her mother’s song again in the back of her head. It rocks her like a lullaby.

‘You can stay here,’ Peggy says, ‘for ninety-nine nights, until the seventh of August, just before midnight. And then you must go.’

‘Sorry?’ Alba wonders if the hot chocolate was spiked with rum because she’s suddenly light-headed. ‘But I couldn’t possibly …’

‘No rent, no bills. Your room will be your own, to do with as you like.’ She smiles, and Alba can almost hear the old woman’s papery skin crinkle. ‘But take care of the house, and it’ll take care of you.’

‘Well, I …’ A thousand questions crowd Alba’s mind, so she asks the first one that comes to her lips. ‘But why ninety-nine nights?’

‘Ah, yes,’ Peggy says. ‘Well, because it’s long enough to help you turn your life around and short enough so you can’t put it off forever.’

‘Oh,’ Alba says, thinking it’ll be impossible to pick up the pieces of her shattered life in such a tiny amount of time, let alone get everything back on track.

‘Oh, it is possible,’ Peggy says. ‘I can promise you that. And you won’t have to do it alone. That’s the point of being here. The house will help you. It’s all yours, except for the tower, which is only mine. And you can never go there. That’s my one rule. Do you understand?’

When Alba nods, it’s clear to them both that she’s staying, even though she hasn’t yet said yes. But how can she say no? A secret tower. How deliciously intriguing. It reminds her of another fairy tale. When Alba first saw the house she thought of Rapunzel, then Sleeping Beauty and now Bluebeard. Alba smiles. She loves fairy tales.

‘If you stay I can promise you this,’ Peggy says. ‘This house may not give you what you want, but it will give you what you need. And the event that brought you here, the thing you think is the worst thing could have happened? When you leave, you’ll realise it was the very best thing of all.’

After showing a sedated, sleepy Alba to her bedroom, Peggy shuffles along the corridor toward the tower, creaks up her own stairs and hurries into her kitchen to find a pile of glittering presents and a cake. An enormous, three-tiered extravaganza, iced with thick white chocolate cream, decorated with sugar flowers and scattered with fresh ones: red and yellow roses, wisteria, sunflowers, bluebells and buttercups. Just as Peggy knew it would be, just as it has been every year for as long as she’s lived in the house. Along with the cake, the kitchen is decorated with a rainbow of balloons, streamers and a banner emblazoned with the words

HAPPY 82ND, PEG!

Still catching her breath, Peggy glances up at the clock and smiles.

‘Eighty-two years, two hours and twenty-nine minutes old.’ She eases herself into the little sky blue chair at the wooden table in front of her cake. After blowing out the candles and cutting herself an extremely large slice, Peggy slowly, methodically begins to devour the first tier and very soon, icing is smeared around her mouth and all over her fingers.

‘Delicious.’ She grins, displaying a mouthful of cake. ‘Even better than my eighty-first. I must say, you outdo yourself every year.’ Peggy looks up and the ceiling lights flicker in appreciation of the compliment.

Peggy’s kitchen is smaller and prettier than the one downstairs. The furniture is made of beech and painted white, excepting the blue chair. Vases, pots and jam jars sit on every surface, filled with flowers that alter according to Peggy’s moods but never wilt or die. The cupboards have glass doors to display a collection of crockery: bone china cups covered with tarot cards that read the future of whoever drinks from them, teapots and plates painted with characters from Alice in Wonderland, ‘Cinderella’, Don Giovanni, ‘The Frog Prince’, ‘The Lady of Shalott’ and ‘The Flower Queen’s Daughter’. The characters shift around at night, indulging in various games and love affairs. They are Peggy’s own celebrity magazines and, when she shuffles in for her first cup of tea every morning, she’s always curious to see who’s fallen in love and who’s split up overnight. Now, on the teapot, Rumpelstiltskin is slipping off Guinevere’s blouse while, on her plate and almost hidden by the remains of a third slice of cake, the Mad Hatter is kissing an Ugly Sister. The Star – the tarot card that always appears on her birthday – shines from her teacup.

Peggy celebrates her birthday twice. First, just after midnight, always alone. Then in the morning, with whoever is residing in the house. Peggy never knows how many guests she’ll have, sometimes as many as twelve. Today, with the arrival of Alba, she’ll have just three: a rare island of calm and tranquillity in a sea of usual confusion and chaos. Though, sadly, Peggy knows the relative peace won’t last. She can already sense several women whose hope is almost extinguished, who’ll be turning up on her doorstep before too long.

The house always joins in the birthday festivities, creaking its beams and rattling its pipes because it’s celebrating too. The house was completed, its last brick laid, on the first of May 1811, and every Abbot woman who has inherited the house since has been born on its anniversary. The house was a gift from the prince regent to his lover Grace Abbot. And when the prince moved on to his next mistress, Grace opened the house to women who needed it. Slowly they came, drawn by their own sixth sense, staying for their ninety-nine nights, and, with a few tragic exceptions, leaving with their spirits high and their hearts healed.

Peggy sips her tea. The tarot card on her cup has changed. Death looks up at her now: the card of beginnings and endings, sudden shifts and dramatic transformations. She puts down her cup.

And on the table is a note:

Congratulations on your 82nd and final birthday. You have been a beautiful landlady. One of the very best. We thank you for your service. Now it is time to find your successor. Then you will be free from this life and can move on to the next.

Peggy has to read the note nearly a dozen times before she can believe it. She knew she couldn’t live forever, but the shock has still left her a little shaken. If she were another sort of woman she might be scared, she might cry and wish for more time. She might look back on her life and be filled with regrets. But Peggy won’t. She is made of stronger stuff. She’s also in the rather unique position of being very well acquainted with a great many departed souls and knows that death is nothing to fear. It’s merely an adjustment in living conditions. In fact, if it wasn’t for Harry, she wouldn’t mind at all.

Peggy holds the cup to her lips, thinking of him, and wondering just how many days of life she has left.

Chapter Two

When Alba wakes all she can see are books. Thousands line every inch of every wall and the ceiling, some drift through the air like birds, lifting off from one shelf and settling on another; precarious stacks are spread across the floor like skyscrapers. For a moment, Alba thinks she’s dreaming.

Slowly, she slides out of the bed, stepping through the city of books to the nearest wall. She reaches up to touch the spines: Tractarians and the Condition of England, Disraeli and the Art of Victorian Politics, The Oxford Movement … Alba stops. When, a little drunk on sugar and cream, she’d stumbled into the room last night, it had been empty except for a bed. Now every historical text she’s ever read is at her fingertips.

Slowly Alba steps back, slips on a pile of books and hits the floor.

‘Shit!’ She snatches up The Liberal Ascendancy and hurls it at the wall. The room watches her silently, waiting. Whispered words float through the air. Alba shakes her head, wishing she could forget. But every seductive sentence Dr Skinner ever said has seared itself onto her skin. At last Alba’s tears begin to fall. She pulls her knees to her chest and sobs.

Peggy is putting off getting out of bed. It is her birthday, after all, so she deserves a little lie-in. From the corner of the room comes a plaintive meow. She smiles at the big fat ginger cat attempting, yet again, to dig his claws into a chair leg.

‘Oh, Mog, when are you going to give that up?’ Peggy pats the bed, feeling a little sorry for her pet who is forever trying and failing to mark the furniture. ‘Now, come and give your mama a hug.’ Lately Peggy has been missing her lover, Harry Landon, a little more than usual. She wants to be cuddled at night and kissed in the morning, though the archaic house rule of no overnight male visitors won’t allow it. And, after last night’s revelation, she’s missing him rather more. Not that she needs comforting. She’s resigned to her fate and isn’t scared. But since she might not have much time left, she’d rather like to spend some of it with him.

Peggy clicks her fingers at the cat. ‘Let it go, Mog, I haven’t got forever any more.’ The cat ambles across the carpet with a yawn. When Mog reaches the bed he stretches up to scratch his claws along the wood and Peggy just sighs, knowing he can’t make a mark.

Mog has haunted the house since it was built. In life he’d belonged to Grace Abbot, but he has been loved and spoilt by her six successors, all Abbot women chosen for their psychic skills, selflessness and sense of duty. But with the passing of her niece last summer, all Peggy has left now are second cousins. And they, without a flicker of foresight or a touch of telepathic thought, will never do. So, for the first time, it seems as though someone outside the family will inherit Hope Street. Perhaps, with her extraordinary sense of sight, Alba might be the one. But she would need extraordinary strength, too, and she doesn’t have that. At least, not yet. The recipe for running the house on Hope Street is special indeed: four parts psychic ability, one part patience, two parts fortitude, three parts altruism, and Peggy has yet to find every ingredient in another woman.

Mog leaps onto the bed, making dips in the duvet as he pads to Peggy’s outstretched hand. When he’s feeling frisky Mog roams the house to startle the residents, who can feel but not see him. After he died, to his never-ending annoyance, Mog has only been able to brush his silky fur against skin and momentarily leave his paw prints on the softest surfaces, but never make satisfyingly solid scratches.

‘Hello, Moggy.’ Peggy settles back into a cloud of pillows to gaze up at the ceiling, while Mog pushes his nose into her armpit. A vast skylight is cut into the ceiling, so she can fall asleep studying the stars. She doesn’t know their real names, preferring mysteries to facts, but loves to trace her fingers along their shapes. She wonders if she’ll be lucky enough to land among them when she dies. Peggy closes her eyes and, a moment later, feels a scrap of paper land on her nose. She picks it up and reads:

I never knew a man come to greatness or eminence who lay abed late in the morning.

‘I need advice about my successor, Anne Abbot.’ Peggy rips the paper into tiny pieces. ‘Not a critique of my sleeping habits. And no one believes you had an affair with Jonathan Swift, no matter how many times you quote him.’

Entirely oblivious, Mog stretches and yawns. Peggy strokes his head, absently scratching his ears until he purrs and starts to drool. Watching the expanding patch of wetness on her sleeve, Peggy sighs. ‘You can sleep in my bed, you little minx, but I draw the line at drool.’

Mog opens a single eye and gives her a reproachful look. While they’re staring at each other, another note floats from the ceiling and settles between Mog’s ears. The cat shakes it off and Peggy picks it up.

Trust yourself and you shall know how to live.

Peggy hears a ripple of laughter through the walls, and sighs. ‘You are all entirely useless.’

Having finally stopped crying, pulled herself off the floor, and yanked open her bedroom door, Alba steps into the hallway. She has a headache, and needs fresh air. At the end of the hallway she finds a balcony and, hoping no one will mind, clicks open the French doors and walks out to lean over the railing. A low mist hangs over the front garden, floating beneath the branches of the willow trees and engulfing the cowslips. In the light Alba can see just how grand the garden is, and how far from the street. Wisteria twists over every inch of the house in a maze of branches and a blanket of flowers. Looking out across the town she can see the tops of every house and tree for miles. All of a sudden Alba is dizzy.

She turns, stumbles back into the hallway and trips over a small wooden stool. She steadies herself against the wall, perplexed because the stool wasn’t there a moment ago. Another wave of dizziness comes over her, and she sits down. She’s stepped into another world, one that makes no sense at all, with objects that don’t have the decency to obey the proper laws of physics. Just like me, Alba realises. Having felt odd and out of place all her life, she’s finally found somewhere she fits perfectly.

From the walls the photographs take surreptitious glances at Alba. She catches the curious eyes of two sisters: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first woman to qualify as a doctor in England, and Millicent Garrett Fawcett, co-founder of Newnham College in 1871. Though, Alba remembers, women weren’t actually awarded degrees until thirty-two years after that. She smiles. The idea that this house has been a temporary home to such prestigious figures sparks a tiny glow of hope inside her. Maybe, just maybe, it can help her too.

Suddenly aware that someone is coming, Alba jumps up off the stool and hurries down the corridor, away from the smell of cigarettes and sex drifting toward her. Alba is only halfway to her bedroom before a voice calls her back.

‘Espera, por favor, espera!’

Alba can’t help turning. At the top of the stairs stands a woman so striking that Alba has to steady herself while she stares. Carmen Viera is tall and voluptuous, about ten years older than Alba, wearing a dress that clings to every curve. She has thick dark curls that float over her shoulders and fall down her back. She makes Alba feel scrawny and unkempt. But as she stares, Alba starts to see something else. The woman is scared, wearing her self-confidence like perfume: a heavy, sultry scent to distract onlookers from the broken, blackened pieces of herself she wants no one else to see. Her body is bruised underneath the dress; purple shadows that linger on, her olive skin scarred with cigarette burns, her heart cracked in so many pieces it’s a wonder it still beats.

‘Hello,’ Alba says, pleased that her sense of sight is already getting stronger.

‘Ola.’ The woman reaches out a delicate hand with long fingers. ‘I am Carmen.’

Alba hurries forward to take it, noticing the manicured nails and suddenly feeling self-conscious of her bitten-down stubs.

‘Muitoprazer.’ Carmen smiles, wondering why this pretty girl is dressed so shabbily, why she hasn’t bothered to brush her messy hair or put on make-up. Carmen doesn’t understand why a woman would want to hide her own beauty. A gift from God should be put on display. Even though she barely believes in God any more, after all that she’s been through, she still believes in this. ‘Okay,’ Carmen says. ‘You come for breakfast now?’

‘Well, um …’ Alba stalls, not at all sure what she’s doing. ‘I—’

‘It’s a special day.’ Carmen cuts her off. ‘The day you come, and Peggy’s birthday. She will make a cake and – qual e a palavra? – yes, pancakes with cherries and cream. She is crazy for this stuff. You will stay for this, celebrate with me and Greer, nao?’

‘I’m not sure … I don’t know,’ Alba says. ‘Who’s Greer?’

‘She lived here a few weeks already.’ Carmen leans against the wall with a little sigh, apparently tired from standing for so long. ‘She is an actress, tall, long red hair, green eyes. I not met her yet but Peggy say she very glamorous.’

Oh, great, Alba thinks, another beautiful one. I’ve stumbled into a cult of extraordinarily beautiful women and I’m their sacrificial virgin. ‘Greer’s a funny name.’

Carmen shrugs, swallowing a comment about pots and kettles she recently heard but can’t now quite recall. ‘She is named from an actress, English with also red hair and many awards.’

‘Oh.’ Alba frowns. She finds films frivolous and knows nothing of actresses. ‘I’ve never heard of her.’

Carmen regards Alba curiously, still not quite able to make sense of her. The new girl seems so timid, so careful, shut up tight as a clam, that Carmen longs to shake her up. She wants to take this little mouse to the bar where she works, get her drunk and see her dance on table tops. Resolving to fulfil this ambition before she leaves the house, Carmen smiles, flashing bright white teeth against olive skin. ‘You will join us for this, nao?’

Unsettled by the directness of the question, Alba gathers herself and considers her options: she’d rather live on the streets than see her family again or, more specifically, her siblings, who will be utterly horrified by what happened. They will interfere, demand to know the truth, and she can’t tell them. Her mother is a different matter. She won’t throw around threats, in fact she won’t say a thing, she’ll just stare at her daughter until both are soaked in sadness. And that is more than Alba can bear at the moment.

‘Yes,’ Alba replies, ‘I’ll join you.’

Greer is nearly forty and has no home, no career and no fiancé. Two weeks ago the abysmal play she was struggling through finally closed. That same night she’d come home to find her fiancé with a twenty-two-year-old on the kitchen table. After throwing saucepans while he declared his love for this new girl, Greer ran out of his flat, wandering through a fog of tears until she finally found herself on Hope Street, standing in the garden of a house she’d never seen before.

After nearly two weeks Greer still isn’t completely used to its strange ways, but it no longer scares her. Like every other resident who lives there – breathing its air, eating its food, drinking its water – she has become entirely enchanted by her new home. Slowly, her heart is beginning to beat in time to its gentle pulse, and her lungs fill with its soft breath.

Now she sits up in bed to see something new in her bedroom: an enormous wooden wardrobe filling the opposite wall, with its doors flung open. Greer stares at rows and rows of clothes, at every kind of theatrical costume she could possibly imagine. To the left are those from her favourite era, the screwball comedies of the 1940s: dozens of A-line dresses and flared trousers, fitted shirts and pencil skirts. To the right, costumes from the 1950s: puffball skirts, halter-style tops and sweetie swing dresses. And in the middle, a row of Jane Austen: empire gowns and summer dresses with matching coats in linen, velvet and silk. Along the floor are vintage shoes, heels and flats, and hanging above the clothes, rows of hats.

‘Oh my God,’ Greer gasps. Of everything she’s seen so far, this is without a doubt her absolute favourite. The wardrobe beckons, enticing her out of bed. In a gap between a blue dress and a red skirt Greer can see the wardrobe is several metres deep. Tentatively she reaches out to the blue dress, hesitant to step inside behind the curtains of cotton and silk, almost expecting to see Mr Tumnus trot out from behind the veils.

A delicate pea green dress catches her eye and the memory rises up again, the one that never really leaves, that always flutters at the edges of her mind. It pushes forward now, and suddenly Greer is numb to everything except the past. Standing in front of a hundred colours, all she can see is her daughter’s face, the bright green eyes blinking up at her. For, despite the doctor’s saying it was impossible, that all babies are born with blue or brown eyes, Lily’s were green. Bright shining green, like leaves lit by sunlight. Greer will never forget gazing into them for the first and last time. The one person she loved more than anyone in the world, she met for only a moment.

Greer bites her lip and swallows the memory, pushing it back to where it belongs, locked in her heart and held there, a private pain that is hers and hers alone. She has to focus on the present now and find something to wear. She’s hardly in the mood to socialise, to shine and smile, but now it’s time. After twelve days of hiding out in her bedroom with a broken heart, she must finally meet her housemates. Greer takes a deep breath. She can do this – she is an actress, after all.

Alba sits at the kitchen table, pushing the remains of a barely touched piece of birthday cake around her plate, sneaking looks at Greer, who’s dressed in a green silk gown with red satin heels and matching bolero, looking as though she’s attending the Oscars, except that she’s hardly smiling. Alba studies the two women: where Carmen is stunning and sexy, Greer is more subtly beautiful. They both dress impeccably. Feeling self-conscious and out of place, Alba tries to think of something to say. Carmen munches her way through the bowl of cherries, Greer chats half-heartedly about a production of Twelfth Night at the theatre in town and Peggy licks out a bowl of cream.

‘How many people live here?’ Alba ventures.

‘That depends on the season.’ Peggy lifts her head up from the bowl, a peak of cream on the tip of her nose. ‘On the weather and the amount of despair in the air. We’re always the most crowded around Christmas.’ She swipes off the cream with her finger. ‘But right now we’re virtually empty. Before you turned up last night it was just the three of us, wasn’t it?’

She looks at Greer, who flashes Alba a film-star smile, and at Carmen, who nods, then accidentally swallows a cherry pip and coughs. Alba glances around the kitchen at the multicoloured helium balloons floating around the room, bobbing in midair just above their heads. How funny, Alba thinks, that they don’t float up to the ceiling.

‘We’re very happy to have you here,’ Peggy says. ‘Aren’t we, girls?’

‘Absolutely.’ Greer grins, momentarily blinding Alba, who blinks. ‘The more the merrier.’

Nodding, Carmen drains her glass and coughs again. ‘Sim, I never have sisters, I always want some. I can take you drinking, we can go shopping, get makeups, go dancing.’ She grins. ‘We will have much fun.’

‘Oh.’ Alba tries not to look too horrified at the suggestion of socialising with someone so luscious and loud, someone with whom she has absolutely nothing in common, excepting the broken heart. ‘Well, um, I don’t really know …’

‘Cream?’ Peggy hides a smile and offers Alba the bowl.

‘No, thanks—’

‘Pancake?’ Greer says perkily, wishing she were upstairs in bed.

‘No, I’m—’

‘Cherry?’ Carmen drops one onto Alba’s plate.

‘No, but’ – Alba eyes it – ‘thank you.’ As she pops the cherry into her mouth, Alba feels a prickle of anticipation along her spine, the same sensation she used to get as a girl the moment before seeing her grandmother’s ghost. She glances up and there, sitting in the kitchen sink, is a young woman: tall, thin and entirely transparent. She’s in her early twenties, very pretty, with long blond hair and blue eyes, wearing a long dress dotted with daisies. She gives a little wave, kicks her transparent legs against the kitchen counter and smiles.

She reminds Alba of hippies, flower power and feminism, of an essay she once wrote about the effects of the pill on the liberation of working-class women in 1960s Britain. The young woman waves again, and it’s only then that Alba realises she is the only one who can see her.

Chapter Three

Alba has scarcely left her bedroom for three days. She’s pulled on a pair of pyjamas and a safety blanket of books and lost herself in the dark labyrinths of Victorian history. The song she heard that first night still floats through the house every night and Alba senses that it’s somehow connected to the ghost. She can’t prove it, but something about the ghost’s smile made her wonder. It was a knowing smile, the sort someone makes when she has a secret and wants to give a hint of it.

Alba shuts her biography of Gladstone, sits up in bed and rubs her eyes, brushing away the last traces of sleep. On the bedside table, atop a pile of books, sits a little slip of white paper. Alba thinks of Alice at the threshold of Wonderland as she picks it up and reads:

You Are Loved

She frowns. What does it mean? Is it a generic statement, or a message of hope suggesting Dr Skinner loves her after all? Both are unlikely, since her ex-supervisor was a fraud, her family barely acknowledge her existence and, being a freak genius with no social skills, she has no friends. In fact, the only person Alba can remotely claim as any sort of friend is Zoë, assistant librarian at the university library, the only human being she’s shared more than three words with on a weekly basis. When they met, Alba instantly liked the short, skinny, spiky-haired girl who looked so much like her, just a little older, prettier and far more friendly. But Alba has never gone beyond small talk and the formalities of book requests, so she really can’t claim to know anything about Zoë beyond her name.

Alba folds the note and tucks it into her pyjama pocket. Perhaps if she keeps it close to her heart for long enough, she’ll be able to work out its message. Or, she could ask someone else. As soon as that thought floats into her head it is followed by another. All at once Alba senses that the ghost is sitting in the kitchen sink, and that she knows something, something worth knowing. Alba loves mysteries. It’s one of the reasons she studied history, the chance to solve all the grand questions of the past. And now she has one on her own doorstep. It’s enough to get her out of bed.

Three minutes later Alba catapults through the kitchen door, the lights flicker on and there is the girl, smiling from her spot in the sink. A little embarrassed at her eager entrance, Alba slides slowly into the nearest chair.

‘Hello,’ Alba ventures, wondering if the ghost can talk.

‘Hello.’

They sit in silence for a few seconds when Alba, too nervous yet to ask about the note, stands and walks to the nearest wall, searching for a familiar face among the photographs to give her something to talk about. She stops at a picture of two women: one tall with curly black hair and a wide-brimmed feather hat, the other with trousers and a pageboy haircut.

‘That’s Vita Sackville-West and Dora Carrington.’ Alba feels the ghost just behind her. ‘This is where they first met, great friends by all accounts, perhaps even a little more than that …’

‘Really?’ Alba asks softly, still conscious of the ghost’s being so close.

‘Oh, yes, you’d be rather surprised by all that’s happened here, stuff you’ll never read about in your history books.’

Alba feels the ghost float away and turns to see her sitting cross-legged in the middle of the kitchen table. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Stella.’

‘Why are you here?’

‘Why are you here?’

Ignoring the question, Alba pulls the note out of her pocket. ‘Do you know what this means?’ She steps forward and slips the paper onto the table. Stella leans down to read it.

‘Ah,’ she says. ‘Yes.’

‘What?’

‘Someone loves you.’

Alba resists the temptation to raise her eyebrows. ‘Yes, that’s what it says. But I was wondering … Well, who?’

‘Ah.’ Stella smiles. ‘That would be telling, now wouldn’t it?’

Greer wakes to find, much to her surprise, that she’s actually feeling rather happy. After two weeks of tears she no longer longs for the fiancé or even cares she lost him at all. It’s possible, she’s starting to realise, that she never really loved him at all. Or maybe it’s that the house is the most comforting, strangely healing place she’s ever been.

She slips out of bed, steps carefully over the piles of clothes strewn across the floor and walks out onto the balcony, her very favourite place in the house. She stands and looks out at the garden. Wind blows a mist of drizzle through the air, dusting Greer with drops, but she doesn’t care: the air is warm, and the water on her face isn’t tears. She can close her eyes without seeing the philandering fiancé. She will sleep without dreaming of him. She will wake without thinking of him. It’s over and done.

An unfamiliar urge nudges Greer and, wiping the misty rain from her face, she turns back to her bedroom and, reaching the bedside table, stops. Next to the red velvet-shaded lamp is a note.

First of all, find a job

Greer sits on her bed with a little sigh. Truthfully, she’s exhausted with her career, if you can call it that. She still adores the thrill of the theatre, but her passion for acting is becoming bloody and bruised from the severe beating it’s taken over a lifetime. Acting has always been everything to Greer. At age six, after being a donkey in the school play, she had wanted only to act every day for the rest of her life. But now, after nearly twenty years of countless failed auditions, innumerable rejections and lacklustre roles, Greer is almost ready to give up. The problem is, having focused on it for so long and having tried so hard, she can’t quite bear to let it go. Anyway she has absolutely no idea what else she could do.

Greer falls back into her pillows, burying her face in them. She wants to keep hiding, to wrap herself up in a ball in the dark. But she can’t. She’ll be out of the house by August and needs gainful employment before then. On the positive side, she thinks, looking for a job will enable her to debut her new dresses. So far, excepting the morning with her housemates, she hasn’t shown them to anyone, which is a shame. Beautiful things are supposed to be worn in public, not hidden away in a wardrobe. It’s not fair to the clothes not to show them off.

Greer has always loved dressing up to go onstage, delighting in the transformation of slipping on a costume. She always preferred glamorous roles to dowdy ones, but even the thrill of pretending to be someone entirely new is something she’ll never tire of. If only the journey from her heart to the stage was an easier one, less fraught with disappointment and heartache. If only she’d fallen in love with a profession that wasn’t so damn difficult to sustain. She could have been a doctor, a lawyer, an architect, earning oodles of cash and enjoying a life of security and success instead of struggle.

With a theatrical sigh, Greer pulls her head out from the pillows and is surprised to see something else. Close to the balcony windows stands a purple dressing table, every inch crowded with bottles: polish, lipsticks, blushers, pencils, eye shadows – all in a dozen different colours. The mirror is huge and edged with light bulbs.

Greer stares at it, speechless. Not taking her eyes off the lights, she untangles herself from the sheets, steps out of bed and tiptoes to the table, as though approaching the last living bird of paradise about to take flight. She reaches the velvet purple chair, presses her palms on its upholstered back, then sits. She picks up a bottle of perfume, sprays a few puffs into the air and lets out a happy sigh. She sweeps her hand over the nail polishes and picks one. In an hour, with nails as red as her hair and a dress to match, Greer will be ready for her next role.

Peggy stands in front of the door to the forbidden room. She’s been knocking for nearly thirty minutes and has had no answer. She’s being ignored. Which is very odd. Ever since she received the note she’s been trying to get into the room, seeking a little advice about what to do next. She needs some help. But, for some reason she’s quite unable to make sense of, the powers that be aren’t giving her any. Peggy’s frustration mounts and she sighs. Then she clenches her fists and gives the door a swift kick. She waits for some sign of life, a sound from the other side. But there is nothing. Just silence.

‘You can’t lock me out forever,’ Peggy snaps. ‘I’ll bash down that bloody door if I have to.’

Carmen is dreaming. She’s three years old, standing at the bottom of her childhood garden, hiding behind her favourite tree. She gazes up at the apple blossoms scattered along the branches: a thousand tiny moons against the evening sky. Her throat is tight and dry and Carmen realises she hasn’t yet spoken a single word aloud. She leans one pudgy hand against the tree trunk, kicks off her shoes and plucks at the grass with her toes, waiting.

A moment later she takes a deep breath and starts to sing. The notes are soft and sweet, their echoes dancing through her tiny body long after they’ve disappeared into the night air. Everything is silent. Carmen looks up at the blossoms, then opens her mouth to sing another note. It sweeps out of her and, caught by a breeze, floats gently through the air. Carmen watches it drift upward, wishing with all her heart she could follow it, gliding above the garden, past the chimney tops and into the clouds. Instead she stands perfectly still, utterly captivated by the sound that has come from within her but seemed to come from somewhere else altogether. It’s so surprising, so beautiful, she laughs. Then, behind the tree, she sees a shadow. Someone else has stepped into her dream. And the sight of him so scares Carmen that it wakes her up.

When Alba opens her eyes she can already feel her sense of sight getting stronger. The hurricane in her head has stilled. She’s stopped shaking. The parts of herself that have been breaking off and scattering into the air are, piece by piece, coming back and beginning to settle. She can see sounds and smells again, just as before, long before she hears or sniffs them. And very gradually, as though looking through an out-of-focus telescope, she’s starting to get a picture of what’s buried under the midnight glory.

Alba knows her senses are stronger now because of the healing powers of the house, and because of Stella. That the ghost appears only to her at least makes Alba feel rather special. They now meet every night, just after midnight.

Alba isn’t intrigued by Stella because she’s a ghost, she’s seen ghosts before, but because she’s a complete mystery. Stella talks about everything but nothing personal, she asks questions but never answers them. So far all Alba really knows is her name; everything else is guesswork. Alba’s fascination with Stella has achieved what, so far, no living person has done: tempt her away from books. In the last few days she’s read only two biographies and three novels: Great Expectations, The Mandarins and Far from the Madding Crowd. Considering her average is usually thirty textbooks a week this is a significant slow-down. And she’s visited the library only once. Now, except for the hours when she reads, Alba talks to Stella all night and sleeps all day.

They talk about everything: literature, history, philosophy, politics, science, art … But most of all, they talk about books. Stella, it seems, has spent her death working through every great work of fiction ever written.

‘What are your top ten books of all time?’ Alba asks. Talking about her greatest passion doesn’t exactly heal Alba’s heart, or solve the problem of what she’s going to do next – but it certainly lifts her spirits.

‘That’s an impossible question.’ Stella laughs. ‘What are yours?’

‘Rebecca. Middlemarch. Mrs Dalloway. Those are my top three, after that I’m not sure,’ Alba admits. ‘Okay then, which books have changed you?’

‘The Golden Notebook,’ Stella says, ‘probably more than any other.’