9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

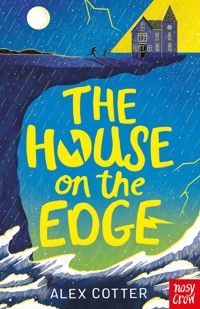

A tense thriller that's impossible to put down - perfect for fans of Emma Carroll and Fleur Hitchcock. Where has Faith's dad gone? Why has he left his family living in an old house perched on a crumbling cliff top? A crack has appeared in the cliff and Faith watches anxiously as it gets bigger and bigger each day... Her brother is obsessed with the sea ghosts he claims live in the basement, and when he disappears as well, Faith starts to believe in the ghosts too. Can she find her brother and bring her father back before everything she cares about falls into the pitiless sea below? A great mystery with real heart, from a captivating new voice in middle-grade fiction. With cover illustration by Kathrin Honesta and neon finishes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

iii

v

For Mae

One

Mum wasn’t always this way. Though without a TARDIS, I can see why you might find that hard to believe. You just see what’s in front of you. Like people walk along the beach and they’ll look up and spot The Lookout. Rising tall and uneven – teetering – right at the edge of the cliff. And their very first thought is: Blimey, that house is going to topple any minute! I swear I see those exact words written on their faces. Sheer fear. That our pebbledash cream walls, our stained slate roof might suddenly fall. Flatten 2them against the sand, like Dorothy’s house landing on the Wicked Witch of the East. When actually – things take much longer to fall than that, right?

“Noah! Answer me: Rice Krispies or Cheerios?”

You have to shout a question to Noah, and you have to shout it at least four times. Before he emerges from deep inside his head, like some hibernating hedgehog blinking into the light – Someone wants me? Away with the fairies, Dad calls it, when Noah glazes over like he’s fixed to a phone. Except Noah never needs a screen.

“Huh?” He lifts his eyes finally. They look bloodshot and swollen. I heard him creep downstairs again last night.

“Krispies or Cheerios?” I shake both boxes impatiently. I don’t even know why I give him the choice.

Noah mumbles, “Krispies,” in a tone like it’s the obvious answer. When last week all he ate was Cheerios. He starts studying me as I pour him a bowl, slop in milk.

“Did you hear it last ni—?” he asks carefully. 3

“No!” I say, before he can finish the question, rolling my eyes for extra measure.

“You really didn’t hear anything?” Noah sits back, incredulous, wedging both hands in his thick red hair so it stands to attention.

“Uh huh, that’s what ‘no’ means,” I tell him, ignoring the niggle in my tummy. What I heard, I remind myself stiffly, are the noises any ancient house by the sea makes: gulls shriek, radiators tick, waves crash, beams creak.

“You can shape sounds into whatever you want,” I tell him in the grown-up, sing-song voice I use a lot lately. “Like the way you can make star signs fit your life.” Which makes me think briefly of Asha (when I’m really trying my best not to), checking hers every day.

“I’m not making it up.” Noah pulls his sulky face. All eyebrows and bottom lip.

I shrug dismissively and turn to put the milk back. I’ve decided it’s best not to give him a “platform”. That’s the posh word this pamphlet in the school library used. All right, so the pamphlet was about OCD and phobias and stuff. But I reckon it’ll have the 4same result. If I don’t encourage Noah’s fantasies, if he’s no one to share them with, hopefully he’ll stop having them altogether.

“Aw, Noah, will you give off night raiding,” I groan, staring into the empty fridge. “I’ll have to shop again now!”

“I haven’t; it’s not me!” Noah complains. Before we both glance up at the familiar creaking sounds above. The house’s way of saying: she’s awake at last. I zip back to the cluttered kitchen counter: kettle for tea, bread in toaster; while I wait: load dishwasher, pack lunches.

“Eat!” I remind Noah what he’s supposed to be doing as I rush out with a mug of milky tea and some heavily buttered toast. Calling back, “You don’t want to be late,” because it’s something Mum would say. The Other Mum that is. The one you’d need a TARDIS to know about.

I slow my pace only when I’ve passed through our tiled, dim alleyway of a hall and I’m facing the stairs alongside our many-greats-grandfather clock. It started after Dad upped and left, I suppose, so 5that’ll be four months and two days ago. (I can give you hours if you want.) I started worrying about our house. Like, really worrying. Just like Dad used to. He says old houses have voices. Now all I hear are The Lookout’s creaks and groans whenever we move. Like every tread I take, up the wonky stairs, or across the uneven wooden floors above, gives it pain.

It’s called The Lookout because our ancestor, Tom Walker, who built it, lit his lantern to warn ships about the rocks below. But I like to think it’s because it takes care of us. Which is why it’s imperative! Quintessential! Unequivocal! And every other big word! That I look after it back. So I climb daintily, like it’s some test and if I fail monsters will get me – moving my feet to the part of the stairs I know are more solid; putting most of my weight on the scratched wooden bannister. Even though the extra strain in my arms makes me think of being little and on Dad’s back on walks; trying my best to be as light as possible so he won’t remember he says I’m getting too heavy to be carried.

The usual small animal noises are coming from 6the bathroom up on the landing. It’s where Mum does most of her crying. I think she reckons if she runs the sink we won’t hear. I pause outside; a weak hand to the door. Then I carry on. Into Mum’s bedroom, where it’s still night-time and it smells of oversleeping and stale breath; musty, like you get in charity shops.

I make space for the tea and toast on her cluttered bedside table, and quickly reach to draw back the curtain for, hooray, light. Hurriedly yank open the wonky window: an impatient burst of cold air rushes in, like it’s been waiting pressed up against the glass all night. The sea gets busy; salt and seaweed set to work on the stuffiness; the rush and smash of waves fill the silence. I’m watching a kestrel hovering motionless above the cliff edge and wondering how it stays so still, when there’s a creak of floorboard; a sniff; a sigh. And Mum appears in the doorway.

“Faith, I keep telling you, you don’t need to bring me my breakfast, love.” Her voice – it’s nothing like it used to be either. The sound of it makes my insides feel empty. It’s too whispery and feathery, like one cough or a sneeze and it’ll fly away completely. 7

And – err, yes, I do, otherwise she doesn’t eat.

“Mmm, yum,” she says, coming over to take a mouse bite of toast, her appreciation-smile looking as exhausted as her eyes and bones. She has on the same pair of Dad’s old blue pyjamas. She rarely gets dressed these days. She’s forever saying, “I’ll get up soon.” Yeah, right. She’s been in bed so long that the back of her hair’s a permanent nest. Her skin’s starting to look as grey as the sea mist outside.

She climbs back under the covers while I tell her I need money to buy food later. I try to keep my eyes from drifting to the side where Dad used to sleep. To his bedside table, where his reading glasses are still sitting on top of his book: Dorset Wreckers, whoever they are.

“Noah can come home by himself,” I say, adding an impatient, “Lots of Year Fives walk back alone,” when she makes a groaning sound.

“They all live right in town, not at the edge of it,” Mum says, fumbling for her credit card from her purse. She holds my eyes as I take it. Hers are watery. “I think I heard Noah going downstairs again in the 8night,” she says timidly.

I look away to roll my eyes. Hold the front page. Noah’s been going down to the cellar every night, for the past two weeks or so. I know that, because I’m the one who has to go out and shout, “Back to bed!” Yeah, OK, so lately, the one who pulls her covers over her head and ignores him. I hate going anywhere near the cellar, especially at night, especially after Dad told us it’s not safe to go down there!

Then why don’t you do something to stop him? Mean Me wants to tell her. Except I won’t, because I’m already fearing what comes next.

“Maybe you and Noah should go and stay with your Uncle Art and Aunty Val after all.”

My heart turns into a fist. I glance back at the perfectly-still kestrel and suck in a deep breath of salt and seaweed. I’ve got to play this right. Talking about it last week ended with me shouting and Mum sobbing uncontrollably.

“I told you, we don’t need them. Noah and I’ve got everything covered.” I swallow back a stream of acid that enters my mouth. “I’ll stop Noah getting up in 9the night, OK? Just don’t even go speaking to Uncle Art!”

Uncle Art can’t know Mum’s in bed all day. He can’t know she’s wearing the same pair of pyjamas for weeks on end. He definitely can’t find out about Noah hearing weird voices in the cellar. My chest’s getting tight. He can’t know I’m doing all the work: cooking, washing, fixing. He’ll use it as an excuse. I know he will. A coldness spreads over my body that doesn’t come from the open window. Uncle Art is just waiting for a reason to get us out of here and have The Lookout condemned.

When I look back again, Mum’s biting her lip hard, like I do when I want to stop myself from crying. “I can’t … can’t … can’t,” she starts telling the bedspread. It’s something else she’s forever saying. You can’t what? Mean Me nearly snaps back, a sudden blaze of anger heating my stomach. Can’t work out the square root of pi? Can’t wait to watch Strictly? Can’t bear Facebook?

“Faith?” Mum pleads, like she can hear inside my head. 10

I drop my chin to my chest and mumble, “Promise you won’t call Uncle Art.”

The waves get louder, till she finally whispers, “OK, I promise,” and the coiled snake that lives in my stomach these days settles down again. I start being as busy as the sea. Showing her we can manage very well without Uncle Art and Aunty Val, thank you very much. I pick up a crusty cardy from the floor, a mug of yesterday’s tea; make a tower of some paperbacks. Before I take quick, soft steps across the floorboards to the door, with a la-di-da, how-responsible-am-I, “Can’t be late for school!”

“Send Noah up for a goodbye kiss,” I hear Mum call out as I reach the stairs. Even shouting, her voice stays fragile and flimsy. Like she’s miles away or sinking fast into quicksand. Whenever I try to remember the sound of her old voice, the way she used to belly-laugh, and sing daft songs and holler “Dinner!” – even the way she’d argue with Dad in the months before he left – I can’t. Maybe you only hear what’s in front of you too.

I’m back downstairs with our many-greats-11grandfather clock, when I start to feel dizzy. Something’s coaxing my stomach snake. I press my hand against the clock’s solid shiny wood to steady myself. It was passed down with The Lookout to our great-greats over three centuries. “And what about the many-great grandmothers?” Old Mum used to say. The fact The Lookout wasn’t passed to women, she said, was another reason to leave. Before Dad went, all she did was list reasons to go (“It’s too isolated!” “Too cold!” “Too unfixable!”). I hear Dad argue back (“It’s my home!” “I can fix it!”).

My stomach snake slinks upwards through my chest. I pincer my lips and fix my mind on the clock’s creamy-white face instead – the pastel picture above the numerals that I’ve always loved. It’s of an old house at sunset, leaning over the top of a cliff while a ship passes below. It never tells the time. The family story goes that ancestor Tom Walker stopped it working the day his daughter died. Removed the pendulum; threw away the key. I trace a finger where his initials T.W. and an X are carved into the wood. “Not a kiss,” Dad said ages ago when I asked, “but 12Tom’s reminder to keep the clock door locked and sealed shut ever since.”

My stomach snake hisses and attacks. Dad again. I pull my hand from the clock like it’s burned me. I don’t understand why my dad would just up and leave, without even a goodbye. If I listen to Mum, he needs time to himself; if I think like Noah, he’s been taken by pirates. But I don’t think like Noah.

I prefer not to wonder where Dad is. The snake retreats.

Like that OCD pamphlet said, it’s better not to give some thoughts a “platform”.

Two

“Is it any bigger?” I say, as Noah joins me in the back garden, finally done with saying goodbye. Mummy’s boy.

He exhales loudly and, typical Noah, doesn’t answer the question but asks one of his own. “Will Mum be OK?”

“Course, stupid!” I straighten up. He’s making his worried eyes. His hands are bunched in the pockets of his grey school trousers that are an inch too small for him, revealing odd socks (one red, one spotty; both holey).

“She just needs some rest still.” It’s 14my new I-have-all-the-answers voice. Cheery. I don’t even say anything when Noah takes Dad’s precious brass telescope out of his coat pocket, putting it to his eye. When Noah knows he’s supposed to keep it safe inside, in the lounge with the old lantern. Both are inscribed with T.W. just like on our many-greats-grandfather clock.

“I’m going to wish for something,” Noah says, as if I’ve just asked what he’s doing. “But there’s no point telling you what it is.”

“Suits me,” I say, my voice a shrug. Dad used to try and convince us Tom Walker’s old maritime telescope was magical. Which obviously I know now is a load of old rubbish. But Noah still likes to believe in lots of things.

“I’m wishing … that you’d listen for once,” he continues importantly, with a dramatic pause. “About the sea ghost in our cellar who I need to help. I told him that Dad—” He stops abruptly at the grunt noise from the back of my throat. We both know we never actually mention the Dad word out loud.

I try again: “Noah – I said, is it any bigger?” 15

There’s another pause while the question journeys to the responsive part of my little brother’s brain. Eventually, he pulls the telescope away and concentrates on The Crack by my feet. The three-metre gash in our back garden that we’ve been watching like it’s a sleeping python since it appeared overnight a week ago. Noah bends closer. The sky seems to come with him, elephant grey and sombre, as if it’s inspecting The Crack too.

He cocks his head to one side and says “Mmm” and “I see” like he’s some expert on Antiques Roadshow. Which he is in a way. Noah’s always been good at observing stuff, spotting things. Things that others don’t. He finds all the lost items people leave on the beach, and all the new objects the waves sweep in, when the sea’s having its spring clean. It’s why his bedroom permanently smells like an aquarium, and looks like a museum, since Mum stopped making him tidy it.

“I think it might have grown a little at that end – and got deeper there,” Noah points, scrunching his mouth up for “sorry”. 16

I clamp my thumbnail between my teeth and stare up at The Lookout. Half a dozen small windows gaze back at me, like it’s waiting for me to pass on Noah’s prognosis. There are only about seven metres between The Crack and our back door. About five the other way, from The Crack to the garden fence. Which is also the edge of the cliff. If it gets any longer, any deeper, it could split our garden in two. Our house too. I rip the end of my nail off and spit it out. Right as Vicious Wind starts circling. It whips brown strands out of my ponytail, using them to thrash my eyes. I never knew I could hate the wind so much. Hissing and howling like invading warriors. Rattling the pipes on the house, playing xylophone with the slates; bringing its friend, Storm, to shave the cliff below, as easily as stripping bark from a tree.

“Give me that,” I say, with a bite I don’t mean, and grab the brass telescope from Noah. Without really thinking, I lift it to my eye, hard against my socket, steeling myself to hear Dad’s voice. Like you hear the sea in a conch shell. Close your eyes and make your 17wish. Open your eyes, and – “Surprise!” Dad would sing – as a pile of presents magically appeared through its lens.

But there are no birthday fairies, like there is no magic – because The Crack in our garden is still there when I re-open my eyes. I grind my teeth, feeling stupid for making the wish in the first place, and swing the telescope around, anywhere but the house, The Crack, the cliff – to a giant tanker on the grey horizon; a fishing boat nearer shore; a couple of dog walkers on Redstone Beach; a boy in an oversized blue parka. I stay with the boy. He’s crouching, like he’s searching for something. He’d better not be a fossil hunter. I hate them almost as much as Vicious Wind. Chipping at the cliff face with their tiny hammers, not caring that the last landslip took away our old garden fence.

I hand the telescope back to Noah, pointing out Blue Parka. “You might have a customer.” Noah gets excited about helping people find their missing things. Except – maybe not today. “Mum’ll take you to school again soon, all right?” I translate his silence. Before I 18tug him towards the back door, Vicious Wind zipping in and out of our legs like it wants to trip us up. While, inside my head, I make another wish, probably for the zillionth time: that I wasn’t the oldest.

Now we’re really running late. Because: no, Noah hadn’t brushed his teeth. And then: oh, no, he’s not remembered to put underwear on. “Would you forget to wee if I didn’t remind you?” I ask breathlessly. We’re having to run-walk and that’s making the worry-pains in my gut worse. They usually come as soon as I can’t see the house any more. When the town starts to gradually creep up on us, after we’ve taken our shortcut along the cliff path above Redstone Beach; round the Second World War pillbox; across the field near the disused well; past Halfpenny Farm and the giant oak; through the metal kissing-gate into St Swithun’s church. Before we rejoin the main road and its rows of brick houses with blank faces and people in coats and cars, on bikes and phones. Noah and I both jump at the thrum of the number 44 passing too close to the pavement, on its way to the bus 19station, then Tesco, then the big town – where Uncle Art lives. Uncle Art. My guts threaten to explode.

We start running for real as Noah’s school bell rings in the distance, sprinting as we round the playground to his class door. I shove him inside when he comes to an abrupt standstill, even though I know just how he feels. I make one of Old Mum’s cheesy thumbs-ups when he looks back uncertainly, holding it till he’s lost to the cloakroom. Then I check the time on my phone – five minutes till my bell goes – and launch back into run mode.

“Noah’s sister! A word, please!”

I should have known this day was only going to get worse.

Mrs Hollowbread. Noah’s ancient teacher. Tight hair bun; broad shoulders; wrinkled prune-mouth sucking on a lemon. She knows my name. She just chooses never to use it. I’ve an urge to keep going, pretend I’ve not heard, but I’ve got to seem responsible, so – “Yes?” I say, bright-and-breathless. Out of the corner of my eye, I notice a boy around my age move down the other side of the railings. I recognise the oversized 20blue parka he’s wearing – the boy on the beach before.

“I told you last week, I need your mother to come in and speak with me,” Mrs Hollowbread says, her voice as brittle as the cuttlefish you find dried-up on the shore. “I’m concerned about Noah.”

“Still?” I ask innocently. “Umm, she can’t right now. A cold.”

Mrs Hollowbread narrows her sharp eyes to paper slits, but I can still read them. I can read all the gossip that’s spreading through the town, as fast and furious as Vicious Wind. That no one’s seen Mum for months. That they’d do this or that, if it were them. That ah, the poor children. And oh, what’s to be done!

“Everyone should make time for their children,” Mrs Hollowbread eventually answers, using a tone aimed to sting. I swear I can see tentacles growing out of her body.

Parka Boy is leaning over the railing now, frown lines on his forehead, like he’s straining to hear the conversation. What’s his problem?

“I’ll get her to call you,” I say, already trying to work out how I’ll make Mum’s feathery voice be heard 21down the phone. How I’ll force her to say the right things: Yes sir, no sir, three bags full sir. What if she cries? What if she starts her, I can’t, can’t, can’t? What if they decide together, we should go to Uncle Art’s? My heart pumps faster. I clench my hands into fists to stop them shaking. Mum can’t call anyone. Not yet.

“Maybe I can help instead?” I say, employing grown-up, sing-song voice.

Which doesn’t wash with Mrs Hollowbread. The lemon in her mouth turns to cyanide; she brandishes a folder from under her arm. I realise too late that she clearly planned this ambush. “I suppose you’ve seen these?”

I gaze down at the pictures she’s showing me, recognising them as Noah’s handiwork straight away. Pencil drawings of distorted faces; flowing hair and missing teeth; popping eyes that look bloodshot even without colour. He’s a good artist, my brother, but I can see Mrs Hollowbread’s not interested in his talent. I sniff and try to keep my expression casual, even appreciative. “He has a unique perspective,” I primly 22repeat something I heard Mum tell his last teacher, when she was Old Mum and taking care of all things Noah.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)