The Inerrant Word E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crossway

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

The Bible stands at the heart of the Christian faith, but now more than ever many question its historical reliability and relevance for life today. In what may become the definitive contemporary evangelical resource on this foundational topic, John MacArthur and a host of pastors, biblical scholars, historians, and theologians defend the doctrine of biblical inerrancy from their various disciplines. With contributions from evangelical leaders such as Kevin DeYoung, R. Albert Mohler Jr., R. C. Sproul, John Frame, and Mark Dever, this comprehensive volume makes the case that God's Word is without error and therefore completely reliable. The contributors explore key Scripture passages, precedents for inerrancy in church history, theological responses to common challenges, and pastoral applications of the doctrine to everyday life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 825

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

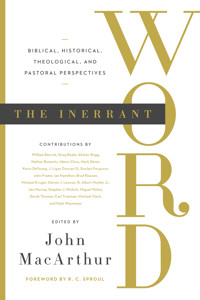

THE INERRANT

WORD

BIBLICAL, HISTORICAL, THEOLOGICAL, AND PASTORAL PERSPECTIVES

John MacArthur

General Editor

FOREWORD BY R. C. SPROUL

The Inerrant Word: Biblical, Historical, Theological, and Pastoral Perspectives

Copyright © 2016 by John MacArthur

Published by Crossway

1300 Crescent Street

Wheaton, Illinois 60187

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law. Crossway® is a registered trademark in the United States of America.

Cover design: Tim Green, Faceout Studio

First printing, 2016

Printed in the United States of America

Chapter 14, “The Use of Hosea 11:1 in Matthew 2:15: Inerrancy and Genre” by G. K. Beale is reprinted with minor edits from Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 55/4 (2012), 697–715, with permission of the publisher.

The Appendix, “The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy,” is reprinted with the permission of the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals.

Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked KJV are from the King James Version of the Bible.

Scripture quotations marked NASB are from The New American Standard Bible®. Copyright © The Lockman Foundation 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995. Used by permission.

Scripture quotations marked NIV are taken from The Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Scripture quotations marked NKJV are from The New King James Version. Copyright © 1982, Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission.

Scripture quotations marked NRSV are from The New Revised Standard Version. Copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. Published by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A.

Scripture quotations marked PHILLIPS are from The New Testament in Modern English, translated by J. B. Phillips ©1972 by J. B. Phillips. Published by Macmillan.

Scripture quotations marked AT are the author’s translation.

All emphases in Scripture quotations have been added by the authors.

ISBN: 978-1-4335-4861-1ePub ISBN: 978-1-4335-4868-0PDF ISBN: 978-1-4335-4862-8Mobipocket ISBN: 978-1-4335-4867-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The inerrant word: biblical, historical, theological, and pastoral perspectives / John MacArthur, general editor; foreword by R. C. Sproul.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4335-4861-1 (hc)

1. Bible—Evidences, authority, etc. I. MacArthur, John, 1939– editor.

BS480.I427 2016

220.1'32—dc23 2015023859

Crossway is a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

RRD 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16

15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Cover PageTitle PageCopyrightForewordR. C. SPROULIntroductionWhy a Book on Biblical Inerrancy Is NecessaryJOHN MACARTHURPart 1INERRANCY IN THE BIBLE: BUILDING THE CASE1The Sufficiency of Scripture25Psalm 19JOHN MACARTHUR2“Men Spoke from God”2 Peter 1:16–21DEREK W. H. THOMAS3How to Know God: Meditate on His WordPsalm 119MARK DEVER4Christ, Christians, and the Word of GodMatthew 5:17–20KEVIN DEYOUNG5Jesus’s Submission to Holy ScriptureJohn 10:35–36IAN HAMILTON6The Nature, Benefits, and Results of Scripture2 Timothy 3:16–17J. LIGON DUNCAN III7Let the Lion Out2 Timothy 4:1–5ALISTAIR BEGGPart 2INERRANCY IN CHURCH HISTORY: SHOWING THE PRECEDENT8The Ground and Pillar of the FaithThe Witness of Pre-Reformation History to the Doctrine of Sola ScripturaNATHAN BUSENITZ9The Power of the Word in the PresentInerrancy and the ReformationCARL R. TRUEMAN10How Scotland Lost Her Hold on the BibleA Case Study of Inerrancy CompromiseIAIN H. MURRAY11How Did It Come to This?Modernism’s Challenges to InerrancySTEPHEN J. NICHOLSPart 3INERRANCY IN THEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE: ANSWERING THE CRITICS12Foundations of Biblical InerrancyDefinition and ProlegomenaJOHN M. FRAME13Rightly Dividing the Word of TruthInerrancy and HermeneuticsR. ALBERT MOHLER JR.14The Use of Hosea 11:1 in Matthew 2:15Inerrancy and GenreG. K. BEALE15Is Inerrancy Inert? Closing the Hermeneutical “Loophole”Inerrancy and IntertextualityABNER CHOU16Can Error and Revelation Coexist?Inerrancy and Alleged ContradictionsWILLIAM BARRICK17The Holy Spirit and the Holy ScripturesInerrancy and PneumatologySINCLAIR B. FERGUSON18How the Perfect Light of Scripture Allows Us to See Everything ElseInerrancy and ClarityBRAD KLASSEN19Words of God and Words of ManInerrancy and Dual AuthorshipMATT WAYMEYER20Do We Have a Trustworthy Text?Inerrancy and Canonicity, Preservation, and Textual CriticismMICHAEL J. KRUGERPart 4INERRANCY IN PASTORAL PRACTICE: APPLYING TO LIFE21The Invincible WordInerrancy and the Power of ScriptureSTEVEN J. LAWSON22The Mandate and the MotivationsInerrancy and Expository PreachingJOHN MACARTHUR23Putting Scripture Front and CenterInerrancy and ApologeticsMICHAEL VLACH24“All That I Have Commanded”Inerrancy and the Great CommissionMIGUEL NÚÑEZAfterwordKeep the FaithJOHN MACARTHURAppendixThe Chicago Statement on Biblical InerrancyGeneral IndexScripture IndexForeword

R. C. Sproul

“The Bible is the Word of God, which errs.” From the advent of neoorthodox theology in the early twentieth century, this assertion has become a mantra among those who want to have a high view of Scripture while avoiding the academic liability of asserting biblical infallibility and inerrancy. But this statement represents the classic case of having one’s cake and eating it too. It is the quintessential oxymoron.

Let us look again at this untenable theological formula. If we eliminate the first part, “The Bible is,” we get “The Word of God, which errs.” If we parse it further and scratch out “the Word of” and “which,” we reach the bottom line:

“God errs.”

The idea that God errs in any way, in any place, or in any endeavor is repugnant to the mind as well as the soul. Here, biblical criticism reaches the nadir of biblical vandalism.

How could any sentient creature conceive of a formula that speaks of the Word of God as errant? It would seem obvious that if a book is the Word of God, it does not (indeed, cannot) err. If it errs, then it is not (indeed, cannot be) the Word of God.

To attribute to God any errancy or fallibility is dialectical theology with a vengeance.

Perhaps we can resolve the antinomy by saying that the Bible originates with God’s divine revelation, which carries the mark of his infallible truth, but this revelation is mediated through human authors, who, by virtue of their humanity, taint and corrupt that original revelation by their penchant for error. Errare humanum est (“To err is human”), cried Karl Barth, insisting that by denying error, one is left with a docetic Bible—a Bible that merely “seems” to be human, but is in reality only a product of a phantom humanity.

Who would argue against the human proclivity for error? Indeed, that proclivity is the reason for the biblical concepts of inspiration and divine superintendence of Scripture. Classic orthodox theology has always maintained that the Holy Spirit overcomes human error in producing the biblical text.

Barth said the Bible is the “Word” (verbum) of God, but not the “words” (verba) of God. With this act of theological gymnastics, he hoped to solve the unsolvable dilemma of calling the Bible the Word of God, which errs. If the Bible is errant, then it is a book of human reflection on divine revelation—just another human volume of theology. It may have deep theological insight, but it is not the Word of God.

Critics of inerrancy argue that the doctrine is an invention of seventeenth-century Protestant scholasticism, where reason trumped revelation—which would mean it was not the doctrine of the magisterial Reformers. For example, they note that Martin Luther never used the term inerrancy. That’s correct. What he said was that the Scriptures never err. Neither did John Calvin use the term. He said that the Bible should be received as if we heard its words audibly from the mouth of God. The Reformers, though not using the term inerrancy, clearly articulated the concept.

Irenaeus lived long before the seventeenth century, as did Augustine, Paul the apostle, and Jesus. These all, among others, clearly taught the absolute truthfulness of Scripture.

The church’s defense of inerrancy rests upon the church’s confidence in the view of Scripture held and taught by Jesus himself. We wish to have a view of Scripture that is neither higher nor lower than his view.

The full trustworthiness of sacred Scripture must be defended in every generation, against every criticism. That is the genius of this volume. We need to listen closely to this recent defense.

Dr. R. C. Sproul

Former President, International Council on Biblical Inerrancy

Orlando, Florida

Advent 2014

Introduction

WHY A BOOK ON BIBLICAL INERRANCY IS NECESSARY1

John MacArthur

It was A. W. Tozer who famously stated, “What comes into our minds when we think about God is the most important thing about us.” The reason for this, Tozer went on to explain, is that deficient views of God are idolatrous and ultimately damning: “Low views of God destroy the gospel for all who hold them.” And again, “Perverted notions about God soon rot the religion in which they appear. . . . The first step down for any church is taken when it surrenders its high opinion of God.”2 As Tozer insightfully observed, the abandonment of a right view of God inevitably results in theological collapse and moral ruin.

Because God has made himself known in his Word, a commitment to a high view of Scripture is of paramount importance. The Bible both reflects and reveals the character of its Author. Consequently, those who deny its veracity do so at their peril. If the most important thing about us is how we think about God, then what we think about his self-revelation in Scripture is of the utmost consequence. Those who have a high view of Scripture will have a high view of God. And vice versa—those who treat the Word of God with disdain and contempt possess no real appreciation for the God of the Word. Put simply, it is impossible to accurately understand who God is while simultaneously rejecting the truthfulness of the Bible.

No church, institution, organization, or movement can rightly claim to honor God if it does not simultaneously honor his Word. Anyone who claims to reverence the King of kings must joyfully embrace his revelation and submit to his commands. Anything less constitutes rebellion against his lordship and receives his express displeasure. To disregard or distort the Word is to show disrespect and disdain for its Author. To deny the veracity of the Bible’s claims is to call God a liar. To reject the inerrancy of Scripture is to offend the Spirit of truth who inspired it.

For that reason, believers are compelled to treat the doctrine of biblical inerrancy with the utmost seriousness. That mandate is especially true for everyone who provides oversight to the church in positions of spiritual leadership. This book is a call to all Christians, and especially those who lead the church, to handle Scripture in a way that honors the God who gave it to us.

Here are four reasons why believers must stand firm on God’s revealed truth.

Scripture Is Attacked, and We Are Called to Defend It

First, the Bible is under constant assault.

Based on Paul’s description of false teachers in 2 Timothy 3:1–9, it is clear that the greatest threat to the church comes not from hostile forces without, but from false teachers within. Like spiritual terrorists, they sneak into the church and leave a path of destruction in their wake. They are wolves in sheep’s clothing (Matt. 7:15), characterized by hypocrisy and treachery, and motivated by insatiable greed and fleshly desires. Thus, every Christian must defend Scripture and use it properly.

The church has been threatened by savage wolves and spiritual swindlers from its earliest days (cf. Acts 20:29). Satan, the father of lies (John 8:44), has always sought to undermine the truth with his deadly errors (Gen. 3:1–5; 1 Tim. 4:1; cf. 2 Cor. 11:4, 14). It is not surprising, then, that church history has often been marked by seasons in which falsehood and deception have waged war against the pure gospel.

Consider, for example, the havoc created by the following six errors: Roman Catholicism, higher criticism, modern cults, Pentecostalism, clinical psychology, and market-driven church-growth strategies. Though each of these historical developments is very different, all of them share a common rejection of the authority of Scripture.

Roman Catholicism exchanged the authority of Scripture for the authority of religious tradition. One of the earliest deceptions to infiltrate the church on a massive scale was sacramentalism—the idea that an individual can connect with God through ritualism or religious ceremony. As sacramentalism gained widespread acceptance, the Roman Catholic Church supposed itself to be a surrogate savior, and people became connected to a system, but not to Christ. Religious ritual became the enemy of the true gospel, standing in opposition to genuine grace and undermining the authority of God and His Word. Many were deluded by the sacramental system. It was a grave danger that developed throughout the Middle Ages, holding Europe in a spiritual chokehold for nearly a millennium. Because they recognized that Christ alone is the head of the church, the Protestant Reformers gladly submitted to his Word as the sole authority within the church. Consequently, they also confronted any false authority that attempted to usurp Scripture’s rightful place, and in so doing, they exposed the corruption of the Roman Catholic system.

Higher criticism exchanged the authority of Scripture for the authority of human reason and atheistic naturalism. Not long after the Reformation, a second major wave of error crashed upon the life of the church: rationalism. As European society emerged from the Middle Ages, the resulting Age of Enlightenment emphasized human reason and scientific empiricism, while simultaneously discounting the spiritual and supernatural. Philosophers no longer looked to God as the explanation for the world; rather, they sought to account for everything in rational, naturalistic, and deistic terms. As men began to place themselves above God and their own reason over Scripture, it was not long until rationalism gained access to the church. Higher-critical theory—which denied the inspiration and inerrancy of the Bible—infiltrated Protestantism through seminaries in both Europe and the United States. So-called Christian scholars began to question the most fundamental tenets of the faith as they popularized quests for the “historical Jesus” and denied Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch. The legacy of that rationalism, in the form of theological liberalism and continual attacks on biblical inerrancy, is yet alive and well. As such, it represents a continued threat to the truth.

Modern cults exchanged the authority of Scripture for the authority of self-appointed leaders such as Joseph Smith, Ellen G. White, and Joseph Rutherford. Arising in the nineteenth century, cult groups such as the Mormons, the Seventh-Day Adventists, and the Jehovah’s Witnesses preyed on the biblical ignorance of their spiritual victims. They claimed to represent pure forms of Christianity. In reality, they merely regurgitated ancient errors such as Gnosticism, Ebionism, and Arianism.

Pentecostalism exchanged the authority of Scripture for the authority of personal revelations and ecstatic experiences. Officially beginning in 1901 under the leadership of Charles Fox Parham, the Pentecostal movement was sparked when some of his students reportedly experienced the gift of tongues. In the 1960s and ‘70s, Pentecostal experientialism began to infiltrate the mainline denominations. This movement, known as the charismatic renewal movement, tempted the church to define truth on the basis of emotional experience. Biblical interpretation was no longer based on the clear teaching of the text, but upon feelings and subjective, unverifiable experiences, such as supposed revelations, visions, prophecies, and intuitions. The Third Wave movement of the 1980s continued the growth of mysticism within the church, convincing people to look for signs and wonders and to listen for paranormal words from God rather than seeking out truth in the written Word of God. People began neglecting the Bible, looking instead for the Lord to speak to them directly. Consequently, the authority of Scripture was turned on its head.

Clinical psychology exchanged the authority of Scripture for the authority of Freudian theories and clinical therapies. In the 1980s, the influence of clinical psychology brought subjectivism into the church. The result was a man-centered Christianity in which the sanctification process was redefined for each individual and sin was relabeled a sickness. The Bible was no longer deemed sufficient for life and godliness; instead, it was replaced with an emphasis on psychological tools and techniques.

Market-driven churches exchanged the authority of Scripture for the authority of felt needs and marketing schemes. At the end of the twentieth century, the church was also greatly damaged by the Trojan horse of pragmatism. Though it looked good on the outside (because it resulted in greater numbers of attendees), the seeker-driven movement of the 1990s quickly killed off any true appetite for sound doctrine. Ear tickling became the norm as “seekers” were treated like potential customers. The church adopted a marketing mentality, focusing on “what works” at the expense of biblical ecclesiology. Pragmatism inevitably gave way to syncretism, because popularity was viewed as the standard of success. In order to gain acceptance in a postmodern society, the church became soft on sin and error. Capitulation was masked as tolerance; compromise redefined as love; and doubt extolled as humility. Suddenly, interfaith dialogues and manifestos—and even interfaith seminaries—began to sprout on the evangelical landscape. So-called evangelicals started to champion the message that “we all worship one God.” And those who were willing to stand for truth were dismissed as divisive and uncouth.

As such examples illustrate, whenever the church has abandoned its commitment to the inerrancy and authority of Scripture, the results have always been catastrophic. In response, believers are called to defend the truth against all who would seek to undermine the authority of Scripture. As Paul wrote, “We destroy arguments and every lofty opinion raised against the knowledge of God, and take every thought captive to obey Christ” (2 Cor. 10:5). Jude similarly instructed his readers to “contend earnestly for the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3 NKJV). In referring to “the faith,” Jude was not pointing to an indefinable body of religious doctrines; rather, he was speaking of the objective truths of Scripture that comprise the Christian faith (cf. Acts 2:42; 2 Tim. 1:13–14).

With eternity at stake, it is no wonder that Scripture reserves its harshest words of condemnation for those who would put lies in the mouth of God. The Serpent was immediately cursed in the garden of Eden (Gen. 3:14), and Satan was told of his inevitable demise (v. 15). In Old Testament Israel, to prophesy falsely was a crime punishable by death (Deut. 13:5, 10), a point vividly illustrated by Elijah’s lethal encounter with the prophets of Baal on Mount Carmel (1 Kings 18:19, 40). God repeatedly issued strong denunciations against all those who undermined or distorted the truth of his Word (cf. Isa. 30:9–13; Jer. 5:29–31; 14:14–16; Ezek. 13:3–9).

The New Testament repudiates false teachers with equal force (cf. 1 Tim. 6:3–5; 2 Tim. 3:1–9; 1 John 4:1–3; 2 John 7–11). God will not tolerate those who tamper with divine revelation. He takes such an offense personally. It is an affront to his character (cf. Jer. 23:25–32). Accordingly, to sabotage biblical truth in any way—by adding to it, subtracting from it, distorting it, or simply denying it—is to invite the wrath of God (Gal. 1:9; 2 John 9–11). But those who love him and his Word are careful to handle it accurately (2 Tim. 2:15), to teach its doctrines soundly, and to defend the church from those who would distort its truth (Titus 1:9; 2 Pet. 3:16–17).

Scripture Is Authoritative, and We Are Called to Declare It

Second, the Bible comes with God’s absolute authority.

The Bible repeatedly testifies to the fact that it is God’s Word. The men who wrote Scripture, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit (2 Pet. 1:19–21), recognized that they were writing God’s words under his direction (cf. Amos 3:7). They acknowledge that fact more than thirty-eight hundred times in the Old Testament alone. Speaking of the Old Testament, Paul explained to the believers in Rome, “For whatever was written in former days was written for our instruction, that through endurance and through the encouragement of the Scriptures we might have hope” (Rom. 15:4; cf. 2 Pet. 1:2; Heb. 1:1). The New Testament authors similarly recognized that their writings (cf. 1 Thess. 2:13), along with those of other New Testament writers (cf. 1 Tim. 5:18; 2 Pet. 3:15–16), were inspired by God and thus authoritative.

That the Bible is the very Word of God is spelled out in 2 Timothy 3:16. There Paul explains that “all Scripture is inspired by God” (NASB). The Greek word translated “inspired” is theopneustos, a compound word literally meaning “God-breathed.” It refers to the entire content of the Bible—that which comes out of his mouth—his Word. The inspiration and sufficiency of Scripture (vv. 16–17) provide the backdrop for the divine charge to preach the Word (4:1–2).

Because it is his inspired Word, Scripture perfectly conveys the truth of whatever God has said. The psalmist said, “The law of the LORD is perfect” (Ps. 19:7); “I hope in your word” (119:81); “Your word is very pure” (119:140 NASB); “Your law is true” (119:142); “All your commandments are true” (119:151). As these examples demonstrate, Scripture reflects the trustworthy character of its Author.

God is so closely linked to his Word that, in some passages, the term Scripture is even synonymous with the name God: “The Scripture . . . preached the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying ‘In you shall all the nations be blessed’” (Gal. 3:8); “Scripture has shut up everyone under sin, so that the promise by faith in Jesus Christ might be given to those who believe” (v. 22 NASB). In these verses, the Bible is said to speak and act as God’s voice. The apostle Paul similarly referred to God’s speaking to Pharaoh (Ex. 9:16) when he wrote, “For the Scripture says to Pharaoh, ‘For this very purpose I have raised you up’” (Rom. 9:17). Thus, believers can be confident that whenever they read the Bible, they are reading the very words of God.

Jesus implied that all of Scripture is inspired as a unified body of truth when he declared, “The Scripture cannot be broken” (John 10:35). The entire Bible is pure and authentic; none of its words can be nullified, because they are all God’s sacred writings (cf. 2 Tim. 3:15). Christ also stressed the divine significance of every detail of Scripture when he said in his Sermon on the Mount, “For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is accomplished” (Matt. 5:18).

Importantly, because God is a God of truth who does not speak falsehood, his Word is also true and incapable of error. The Author of Scripture calls himself the essence of truth (Isa. 65:16), and the prophet Jeremiah ascribes the same quality to him: “The LORD is the true God” (Jer. 10:10). The writers of the New Testament also equated God with truth (e.g. John 3:33; 17:3; 1 John 5:20), and both Testaments emphasize that God cannot lie (Num. 23:19; Titus 1:2; Heb. 6:18). Thus, the Bible is inerrant because it is God’s Word, and God is a God of truth (Prov. 30:5). Accordingly, those who deny the doctrine of inerrancy dishonor God by casting doubt on the truthfulness and trustworthiness of that which he has revealed.

Scripture Is Accurate, and We Are Called to Demonstrate It

Third, the Bible is demonstrably true.

Despite the attacks of the skeptics and critics, the testimony of Scripture has stood the test of time. It has proven itself to be accurate—historically, geographically, archaeologically, and so on—time and time again.

Though the accuracy of Scripture can be demonstrated in a variety of ways, two of the most compelling involve science and prophecy.

THE BIBLE AND SCIENCE

To any honest observer, the legitimate findings of science (meaning that which can be tested using the scientific method) correspond perfectly to what the Bible reveals. For example, Scripture presents the most plausible understanding of the origins of the universe and the existence of life. The Bible’s teaching that God created the world makes far more sense than the notion that everything spontaneously generated from nothing, which is what the atheistic presuppositions of evolution require.

The renowned nineteenth-century philosopher Herbert Spencer was well known for demonstrating the relevance of science to philosophy. He articulated five knowable categories in the natural sciences: time, force, motion, space, and matter. Spencer’s insights were applauded when he publicized them. Yet they were hardly innovative. Genesis 1:1, the first verse in the Bible, says, “In the beginning [time], God [force] created [motion] the heavens [space] and the earth [matter].” The Creator made the truth clear in the very first verse of biblical revelation.

The record of Scripture is accurate when it intersects with the fundamental findings of modern science. The first law of thermodynamics, which deals with the conservation of energy, is implied in passages such as Isaiah 40:26 and Ecclesiastes 1:10. The second law of thermodynamics indicates that although energy cannot be destroyed, it is constantly going from a state of order to disorder. This law of entropy corresponds to the fact that creation is under a divine curse (Genesis 3), such that it groans (Rom. 8:22) as it heads toward its ultimate ruin (2 Pet. 3:10–13) before being replaced with new heavens and the new earth (Revelation 21–22). Findings from the science of hydrology are foreshadowed in places such as Ecclesiastes 1:7; Isaiah 55:10; and Job 36:27–28. And calculations from modern astronomy, regarding the countless number of stars in the universe, are anticipated in Old Testament passages such as Genesis 22:17 and Jeremiah 33:22.

The book of Job is one of the oldest books in the Bible, written some thirty-five hundred years ago. Yet it has one of the clearest statements of the fact that earth is suspended in space. Job 26:7 says that God “hangs the earth on nothing.” Other ancient religious books make ridiculous scientific claims, including the notion that the earth rests on the backs of elephants. But when the Bible speaks, it does so in a way that corresponds to what scientific discoveries have found to be true about the universe.

Many additional examples could be cited. But this is sufficient to make the point: though the Bible was not written as a technical scientific manual, it is accurate whenever it addresses scientific phenomena. That is precisely what we would expect, since it is the revelation of the Creator himself. When God speaks about this world that he made, he does so in a way that accurately corresponds to reality.

THE BIBLE AND PROPHECY

Scripture’s amazing accuracy can also be seen by looking at the incredible record of biblical prophecy. The Bible’s ability to predict the future cannot be explained apart from the recognition that God is its Author. For example, the Old Testament contains more than three hundred references to the Messiah that were precisely fulfilled by Jesus Christ.

Consider the following messianic prophecies from just one Old Testament passage—Isaiah 53. In this chapter, written some seven hundred years before the birth of Christ, the prophet Isaiah explained that:

•the Messiah would not come in the trappings of royal majesty (v. 2); consequently, he would be despised and rejected by the nation of Israel (v. 3);

•he would be a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief (v. 3), yet he would bear the griefs and sorrows of the nation (v. 4);

•he would be pierced through for the sins of others (v. 5);

•he would be scourged (v. 5);

•God would place the iniquity of the people on him (v. 6);

•though oppressed in judgment and falsely accused, he would not open his mouth in self-defense; rather, he would be like a lamb led to slaughter (v. 7);

•he would be killed for the transgressions of the people (v. 8);

•though he would be assigned a grave for wicked men, he would be buried in a rich man’s tomb (v. 9);

•he would be crushed by God as a guilt offering for sin (v. 10);

•after his death, he would see the fruit of his labors (implying that he would be raised from the dead) (v. 10);

•he would bring justification to many by bearing their iniquities (v. 11); and

•he would be richly rewarded for his faithfulness (v. 12).

Isaiah 53 clearly describes the Lord Jesus Christ. Yet it was penned seven centuries before the events it describes. It is difficult to imagine a more vivid illustration of the divine quality that Scripture possesses, since only God could know the future with such detailed precision.

The Bible includes many other prophecies as well. For example, Isaiah 44–45 predicted the rise of a Persian ruler named Cyrus who would allow the Jewish people to return from their captivity. That prophecy was fulfilled one hundred and fifty years later, exactly as it had been foretold. Ezekiel 26 foretold the total destruction of the Phoenician city of Tyre. That prediction came true some two hundred and fifty years later, during the conquest of Alexander the Great. The Assyrian city of Nineveh serves as a similar example. Though it was one of the most formidable and feared cities of the ancient world, the prophet Nahum predicted that it would soon be destroyed (Nah. 1:8; 2:6). Its collapse occurred just as the prophet declared.

These and hundreds of other examples prove the Bible to be exactly what it claims to be: revelation from the One who knows the beginning from the end (Isa. 46:10).

Scripture Is Active through the Power of the Spirit, and We Are Called to Deploy It

Finally, the Bible is not a dead letter, but the living and powerful Word of God (Heb. 4:12).

Some books can change a person’s thinking, but only the Bible can change the sinner’s nature. It is the only book that can totally transform someone from the inside out. When God’s Word is proclaimed and defended, it goes forth with Spirit-generated power.

It is the Holy Spirit who empowers the proclamation of the gospel (1 Thess. 1:5; 1 Pet. 1:12), convicting the hearts of unbelievers through the preaching of the Word (cf. Rom. 10:14) so that they respond in saving faith (1 Cor. 2:4–5). As the Lord himself promises, “So shall My word be that goes forth from My mouth; it shall not return to Me void, but it shall accomplish what I please, and it shall prosper in the thing for which I sent it” (Isa. 55:11 NKJV). The apostle Paul similarly describes the Word of God as “the sword of the Spirit” (Eph. 6:17). And the author of Hebrews declares: “For the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (4:12).

Thus, the proclamation of the Word is far more than empty noise or lifeless oratory. Because it is empowered by the Spirit of God, the truth of Scripture cuts through barriers of sin and unbelief. Yet, God’s Word is more than just a sword. It is the means by which the Spirit of God regenerates the heart (cf. Eph. 5:26; Titus 3:5; James 1:18), sanctifies the mind (John 17:17), produces spiritual growth (2 Tim. 3:16–17; 1 Pet. 2:1–3), and conforms believers into the image of Christ (2 Cor. 3:18).

It is the Spirit who makes it possible for “the word of Christ [to] dwell in you richly” (Col. 3:16), a phrase that parallels Paul’s instruction to “be filled with the Spirit” (Eph. 5:18), so that believers can manifest the fruit of a transformed life by expressing praise to God and love for others (cf. Eph. 5:19–6:9; Col. 3:17–4:1).

The Holy Spirit not only inspired the Scriptures (2 Pet. 1:21), he also energizes and illumines them, meaning that he enables their life-giving and life-sustaining work. As a result, sinners are rescued from the domain of darkness and transferred into the kingdom of the Savior (Col. 1:13). They become new creatures in Christ, having been born again through the Spirit’s power (John 3:1–8). Their lives are changed forever: they are given new desires, motives, and affections. That internal change of heart inevitably manifests itself in an external change of behavior, such that they are no longer characterized by the lusts of the flesh but instead exhibit the fruit of the Spirit (cf. Rom. 8:9–13; Gal. 5:16–23). Only the Bible can effect that kind of change in people’s lives, because only the Bible is empowered by the Spirit of God.

Conclusion

In a day when the Word of God is under assault, not just from those outside the church but also from those who profess to be Christians, it is the sacred duty of all who love the Lord to contend earnestly for his revealed truth. As we have briefly discussed in this introduction, we ought to do so because when sound doctrine is attacked, we are duty-bound to defend the faith. We take our stand boldly, knowing that we do so on the basis of God’s very authority. Moreover, we advance with confidence, not only because the veracity of Scripture can be convincingly demonstrated, but also because the Word we proclaim is empowered by the Spirit of God. Though God’s truth may be unpopular in our modern age, it will never return void, but will always accomplish the purposes for which God designed it.

To preach, teach, and defend the Scriptures is both our sacred privilege and our solemn responsibility. My prayer is that the pages that follow will instill both certainty and courage in your heart and mind—the certainty that comes from knowing God’s Word is absolutely true, and the courage that is needed to stand for that conviction.

1 In places throughout this introduction, I have adapted material from the following: John MacArthur, “Preach the Word: Five Compelling Motivations for the Faithful Expositor,” The Master's Seminary Journal 22, no. 2 (Fall 2011): 163–77; John MacArthur, Nothing But the Truth: Upholding the Gospel in a Doubting Age (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 1999); John MacArthur, Strange Fire: The Danger of Offending the Holy Spirit with Counterfeit Worship (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2013); and John MacArthur, You Can Trust the Bible (Chicago: Moody Press, 1988).

2 A. W. Tozer, The Knowledge of the Holy (New York: HarperCollins, 1961), 1, 3–4.

Part 1

INERRANCY IN THE BIBLE

Building the Case

1

The Sufficiency of Scripture

PSALM 19

John MacArthur

Psalm 19 is the earliest biblical text that gives us a comprehensive statement on the superiority of Scripture. It categorically affirms the authority, inerrancy, and sufficiency of the written Word of God. It does this by comparing the truth of Scripture to the breathtaking grandeur of the universe, and it declares that the Bible is a better revelation of God than all the glory of the galaxies. Scripture, it proclaims, is perfect in every regard.

The psalm thereby sets Scripture above every other truth claim. It is a sweeping, definitive affirmation of the utter perfection and absolute trustworthiness of God’s written Word. There is no more succinct summation of the power and precision of God’s written Word anywhere in the Bible.

Psalm 19 is basically a condensed version of Psalm 119, the longest chapter in all of Scripture. Psalm 119 takes 176 verses to expound on the same truths Psalm 19 outlines in just eight verses (vv. 7–14).

Every Christian ought to affirm and fully embrace the same high view of Scripture the psalmist avows in Psalm 19. If we are going to live in obedience to God’s Word—especially those who are called to teach the Scriptures—we need to do so with this confidence in mind.

After all, faith (not moralism, good works, vows, sacraments, or rituals, but belief in Christ as he is revealed in Scripture) is what makes a person a Christian. “Without faith it is impossible to please him, for whoever would draw near to God must believe that he exists and that he rewards those who seek him” (Heb. 11:6); “For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works” (Eph. 2:8–9a).

The only sure and safe ground of true faith is the Word of God (2 Pet. 1:19–21). It is “the word of truth, the gospel of [our] salvation” (Eph. 1:13). For a Christian to doubt the Word of God is the grossest kind of self-contradiction.

When I began in ministry nearly half a century ago, I fully expected I would need to deal with assaults against Scripture from unbelievers and worldlings. I was prepared for that. Unbelievers by definition reject the truth of Scripture and resist its authority. “The mind that is set on the flesh is hostile to God, for it does not submit to God’s law; indeed, it cannot” (Rom. 8:7).

But from the beginning of my ministry until today, I have witnessed—and had to deal with—wave after wave of attacks against the Word of God coming mostly from within the evangelical community. Over the course of my ministry, virtually all of the most dangerous assaults on Scripture I’ve seen have come from seminary professors, megachurch pastors, charismatic charlatans on television, popular evangelical authors, “Christian psychologists,” and bloggers on the evangelical fringe. The evangelical movement has no shortage of theological tinkerers and self-styled apologists who seem to think the way to win the world is to embrace whatever theories are currently in vogue regarding evolution, morality, epistemology, or whatever—and then reframe our view of Scripture to fit this worldly “wisdom.” The Bible is treated like Silly Putty, pressed and reshaped to suit the shifting interests of popular culture.

Of course, God’s Word will withstand every attack on its veracity and authority. As Thomas Watson said, “The devil and his agents have been blowing at scripture light, but could never prevail to blow it out—a clear sign that it was lighted from heaven.”1 Nevertheless, Satan and his minions are persistent, seeking to derail believers whose faith is fragile or to dissuade unbelievers from even considering the claims of Scripture.

To make their attacks more subtle and effective, the forces of evil disguise themselves as angels of light and servants of righteousness (2 Cor. 11:13–15). That’s why the most dangerous attacks on Scripture come from within the community of professing believers. These evil forces are relentless, and we need to be relentless in opposing them.

Over the years, as I have confronted the various onslaughts of evangelical skepticism, I have returned to Psalm 19 again and again. It is a definitive answer to virtually every modern and postmodern attack on the Bible. It offers an antidote to the parade of faulty ministry philosophies and silly fads that so easily capture the fancy of today’s evangelicals. It refutes the common misconception that science, psychology, and philosophy must be mastered and integrated with biblical truth in order to give the Bible more credibility. It holds the answer to what currently ails the visible church. It is a powerful testimony about the glory, power, relevance, clarity, efficacy, inerrancy, and sufficiency of Scripture.

In this chapter, I want to focus on a passage in the second half of the psalm—verses 7–9, which speak specifically about the Scriptures.

This is a psalm of David, and in the opening six verses, he speaks of general revelation. As a young boy tending his father’s sheep, he had plenty of time to gaze at the night sky and ponder the greatness and glory of God as revealed in nature. That’s what he describes in the opening lines of the psalm: “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork” (v. 1). Through creation, God reveals himself at all times, across all language barriers, to all people and nations: “Day to day pours out speech, and night to night reveals knowledge. There is no speech, nor are there words, whose voice is not heard. Their voice goes out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world” (vv. 2–4). God declares himself in his creation day and night, unceasingly. The vastness of the universe, all the life it contains, and all the laws that keep it orderly rather than chaotic are a testimony to (and a manifestation of) the wisdom and glory of God.

As grand and glorious as creation is, however, we cannot discern all the spiritual truth we need to know from it. General revelation does not give a clear account of the gospel. Nature tells us nothing specific about Christ; his incarnation, death, and resurrection; the atonement he made for sin; the doctrine of justification by faith; or a host of other truths essential to salvation and eternal life.

Special revelation is the truth God has revealed in Scripture. That is the subject David takes up in the second half of the psalm, beginning in verse 7. Having extolled the vast glory of creation and the many marvelous ways it reveals truth about God, he turns to Scripture and says the written Word of God is more pure, more powerful, more permanent, more effectual, more telling, more reliable, and more glorious than all the countless wonders written across the universe:

The law of the LORD is perfect,

reviving the soul;

The testimony of the LORD is sure,

making wise the simple;

The precepts of the LORD are right,

rejoicing the heart;

The commandment of the LORD is pure,

enlightening the eyes;

The fear of the LORD is clean,

enduring forever;

The rules of the LORD are true,

and righteous altogether. (Ps. 19:7–9)

In those three brief verses, David makes six statements—two in verse 7, two in verse 8, and two in verse 9. He uses six titles for Scripture: law, testimony, precepts, commandment, fear, and rules. He lists six characteristics of Scripture: it is perfect, sure, right, pure, clean, and true. And he names six effects of Scripture: it revives the soul, makes wise the simple, rejoices the heart, enlightens the eyes, endures forever, and produces comprehensive righteousness.

Thus, the Holy Spirit—with an astounding and supernatural economy of words—sums up everything that needs to be said about the power, sufficiency, comprehensiveness, and trustworthiness of Scripture.

Notice, first of all, that all six statements have the phrase “of the LORD”—just in case someone might question the source of Scripture. This is the law of the Lord—his testimony. These are the precepts and commandments of God himself. The Bible is of divine origin. It is the inspired revelation of the Lord God.

By breaking down these three couplets and looking at each phrase, we can begin to gather a sense of the power and greatness of Scripture. Again, the opening verses of the psalm were all about the vast glory revealed in creation. Thus, the central point of this psalm is that the grandeur and glory of Scripture is infinitely greater than the entire created universe.

God’s Word Is Perfect, Reviving the Soul

David makes his point powerfully yet simply in the first statement he makes about Scripture in verse 7: “The law of the LORD is perfect, reviving the soul.” The Hebrew word translated as “law” is torah. To this day, Jews use the word Torah to refer to the Pentateuch (the five books penned by Moses). Those five books, of course, are the starting point of the Old Testament—but the Psalms and Prophets are likewise inspired Scripture, equally authoritative (cf. Luke 24:44). So when David speaks of “the law of the LORD” in this context,” he has the whole canon in mind. “The law,” as the term is used here, refers not merely to the Ten Commandments; not just to the 613 commandments that constitute the mitzvot of Moses’s law; not even to the Torah considered as a unit. David is using the word as a figure of speech to signify all of Scripture.

Throughout Scripture, “the law” often refers to the entire canon. This kind of expression is called synecdoche, a figure of speech in which part of something is used to represent the whole. You find this same language in Joshua 1:8, for example. That verse famously speaks of “this Book of the Law,” meaning not just the commandments, but all of Scripture as it existed in Joshua’s time—Genesis and Job as well as Leviticus and Deuteronomy. Psalm 119 repeatedly uses the same figure of speech (cf. vv. 1, 18, 29, 34, 44, etc.).

When used this way, the language stresses the didactic nature of God’s Word. “Blessed is the man whom you discipline, O LORD, and whom you teach out of your law” (Ps. 94:12); “Graciously teach me your law!” (Ps. 119:29). David is thinking of Scripture as a manual on righteous human behavior—all Scripture, not merely Moses’s law. After all, “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work” (2 Tim. 3:16–17).

And all of it is “perfect.” Many years ago, I researched that word as it appears in the Hebrew text. It’s the Hebrew word tâmîym, which is variously translated in assorted English versions as “unblemished,” “without defect,” “whole,” “blameless,” “with integrity,” “complete,” “undefiled,” or “perfect.” I traced the Hebrew word through several lexicons to try to discern whether there might be some nuance or subtlety that would shade our understanding of it. I spent three or four hours looking up every use of that word in the biblical text. In the end, it was clear: the word means “perfect.” It is an exact equivalent of the English word in all its shades of meaning.

David is using the expression in an unqualified, comprehensive way. Scripture is superlative in every sense. Not only is it flawless, but it is also sweeping and thorough. That’s not to suggest that it contains everything that can possibly be known. Obviously, the Bible is not an encyclopedic source of information about every conceivable subject. But as God’s instruction for man’s life, it is perfect. It contains everything we need to know about God, his glory, faith, life, and the way of salvation. Scripture is not deficient or defective in any way. It is perfect in both its accuracy and its sufficiency.

In other words, it contains everything God has revealed for our spiritual instruction. It is the sole authority by which to judge anyone’s creed (what they believe), character (what they are), or conduct (what they do).

More specifically, according to our text, Scripture is perfect in its ability to revive and transform the human soul. “For the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (Heb. 4:12). For believers, the piercing and soul work described in that verse is a wholly beneficial procedure, comparable to spiritual heart surgery. It is that process described in Ezekiel 36:26, where the Lord says: “I will give you a new heart, and a new spirit I will put within you. And I will remove the heart of stone from your flesh and give you a heart of flesh.” The instrument God uses in that process is the sword of the Spirit, which is the Word of God. “Of his own will he brought us forth by the word of truth” (James 1:18). Jesus said, “The words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life” (John 6:63b). David acknowledges the life-giving principle of God’s Word by saying, “The law of the LORD is perfect, reviving the soul” (Ps. 19:7).

In the Hebrew text, the word for “soul” is nephesh. As used here, the idea stands in contrast to the body. It speaks of the inner person. If you trace the Hebrew word nephesh through the Old Testament, you will find that in the most popular English versions of the Bible, it is translated in a dozen or more ways. It can mean “creature,” “person,” “being,” “life,” “mind,” “self,” “appetite,” “desire,” or “soul”—but it is normally used to signify the true person, the you that never dies.

So what is the statement saying? Scripture, in the hands of the Holy Spirit, can revive and regenerate someone who is dead in sin. Nothing else has that power—no manmade story, no clever carnal insight, no deep human philosophy. The Word of God is the only power that can totally transform the whole inner person.

God’s Word Is Trustworthy, Imparting Wisdom

The second half of Psalm 19:7 turns the diamond slightly and looks at a different facet of Scripture: “The testimony of the LORD is sure, making wise the simple.” Here Scripture is spoken of as God’s self-revelation. A testimony is the personal account of a reliable witness. That word is normally reserved for formal, solemn statements from firsthand sources—usually either in legal or religious contexts. An eyewitness gives sworn testimony in court. A believer relates how he or she came to faith, and we call that a testimony. The word conveys the idea of a formal declaration from a trustworthy source.

Scripture is God’s testimony. This is God’s own account of who he is and what he is like. It is God’s self-disclosure. How wonderful that God has revealed himself in such a grand and voluminous way—sixty-six books (thirty-nine in the Old Testament, twenty-seven in the New), all revealing truth about our God so that we may know him and rest securely in the truth about him.

“The testimony of the LORD is sure.” That is its central characteristic. It is true. It is reliable. It is trustworthy.

The world is full of books you cannot trust. As a matter of fact, any book written by man apart from the inspiration of the Holy Spirit will contain errors and deficiencies of various kinds. But the Word of the Lord is absolutely reliable. Every fact, every claim, every doctrine, and every statement of Scripture comes to us in “words not taught by human wisdom but taught by the Spirit” (1 Cor. 2:13a).

And what is the impact of this? Scripture “mak[es] wise the simple.” “Simple” is the translation of a Hebrew expression that speaks of naive ignorance. It can be used as a disparaging term, describing people who are callow, gullible, or just silly. It’s the same Hebrew word used in Proverbs 7:7, “I have seen among the simple, I have perceived among the youths, a young man lacking sense,” and 14:15a, “The simple believes everything.” The term signifies someone without knowledge or understanding.

But the derivation of the word suggests the problem is not a learning disability or sheer stupidity. The Hebrew root means “open,” suggesting the image of an open door. Many Hebrew words paint vivid images. As a rule, Hebrew is not abstract, esoteric, or theoretical like Greek. This particular expression is a classic example. It embodies the Hebrew idea of what it means to be simpleminded: a door left standing open.

People today like to be thought of as open-minded. To an Old Testament Jew, that would be the essence of half-wittedness. To say that you have an open mind would be to declare your ignorance. It would be very much like modern agnosticism. Agnostics pretend to have an enlightened worldview, and the typical agnostic likes to assume the air and attitudes of an intellectual who is privy to advanced understanding. But the word agnostic is a combination of two Greek words meaning “without knowledge.” To call oneself an agnostic is to make a declaration of one’s ignorance. The Latin equivalent would be ignoramus.

It’s neither healthy nor praiseworthy to have a constantly open mind with regard to one’s beliefs, values, and moral convictions. An open door permits everything to go in and out. This is the attitude that makes so many people today vacillating, indecisive, and double-minded—unstable in all their ways (James 1:8). They have no anchor for their thoughts, no rule by which to distinguish right from wrong, and therefore no real convictions. They simply lack the tools and mental acuity to discern or make careful distinctions. That way of thinking is nothing to be proud of.

If you were able to tell a devout Old Testament believer that you are open-minded, he might say, “Well, close the door.” You need to know what to keep in and what to keep out. You have a door on your house, and you close it to keep some things in (children, heat, cooled air, or the family pet) and other things out (burglars, insects, and door-to-door salesmen). You open it only when you want to let something or someone in. The door is a point of discretion. It’s the place where you distinguish between what should be let in and what should be kept out. In fact, your door may have a peephole that you can look through to help you in discerning who’s going to get in and who’s not.

Our minds should function in a similar fashion. There’s no honor in letting things in and out indiscriminately. We need to close the door and carefully guard what goes in and out (Prov. 4:23).

The Word of God has the effect of making simple minds wise for that very purpose. It teaches us discernment. It trains our senses “to distinguish good from evil” (Heb. 5:14b).

The Hebrew word translated as “wise” in Psalm 19:7 is not speaking of theoretical knowledge, philosophical sophistication, intellectual prowess, smooth speech, cleverness, or any of the other things that define worldly wisdom. Biblical wisdom is about prudent living. The word wise describes someone who walks and acts sensibly and virtuously: “Whoever trusts in his own mind is a fool, but he who walks in wisdom will be delivered” (Prov. 28:26). The truly wise person recognizes what is good and right, then applies that simple truth to everyday life.

In other words, the wisdom in view here has nothing to do with intelligence quotients or academic degrees. It has everything to do with truth, honor, virtue, and the fruit of the Spirit. Indeed, “the fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom, and the knowledge of the Holy One is insight” (Prov. 9:10).

There’s only one document in the entire world that can revive a spiritually dead soul and make him spiritually wise. No book penned by mere men could possibly do that, much less give us skill to live well in a world cursed by sin. There is no spiritual life, salvation, or sanctification apart from Scripture.

We all desperately need that transformation. It is not a change we can make for ourselves. All the glory on display in creation is not enough to accomplish it. Only Scripture has the life-giving, life-changing power needed to revive a spiritually dead soul and make the simple wise.

God’s Word Is Right, Causing Joy

Psalm 19:8a gives a third statement about the perfect sufficiency of Scripture: “The precepts of the LORD are right, rejoicing the heart.” The Hebrew noun translated as “precepts” (“statutes” in some versions) denotes principles for instruction. Close English synonyms would be canons, tenets, axioms, principles, and even commands. All those shades of meaning are inherent in the word. It includes the principles that govern our character and conduct, as well as the propositions that shape our convictions and our confession of faith. It covers every biblical precept, from the basic ordinances governing righteous behavior to the fundamental axioms of sound doctrine. All of these are truths to be believed.

That’s because they are “right.” David does not mean merely right as opposed to wrong (although that’s obviously true). The Hebrew word means “straight” or “undeviating.” It has the connotation of uprightness, alignment, and perfect order. The implication is that the precepts of Scripture keep a person going in the right direction, true to the target.

Notice that there is progress and motion in the language. The effect of God’s Word is not static. It regenerates, restoring the soul to life. It enlightens, taking a person who lacks discretion and transforming him into one who is skilled in all manner of living. It then sanctifies—setting him on a right path and pointing him in a truer direction. “Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path” (Ps. 119:105).

But Scripture is not only a lamp and a light; it is the living voice that tells us, “This is the way, walk in it” when we veer to the right or the left (Isa. 30:21). We desperately need that guidance. “There is a way that seems right to a man, but its end is the way to death” (Prov. 16:25). Scripture makes the true way straight and clear for us.

The result is joy: “The precepts of the LORD are right, rejoicing the heart” (Ps. 19:8a). If you are anxious, fearful, doubting, melancholy, or otherwise troubled in heart, learn and embrace God’s precepts. The truth of God’s Word not only will inform and sanctify you, but it also will bring joy and encouragement to your heart.

This is true especially in times of trouble. Worldly wisdom’s typical answers to despondency and depression are all empty, useless, or worse. Every form of self-help, self-esteem, and self-indulgence promises joy, but in the end, such things bring only more despair. The truth of Scripture is a sure and time-tested anchor for troubled hearts. And the joy it brings is true and lasting.

The life-giving, life-changing power mentioned in verse 7 is the reason for the joy mentioned in verse 8. David, who wrote this psalm, knew that joy firsthand. So did the author of Psalm 119, who wrote, “This is my comfort in my affliction, that your promise gives me life” (v. 50); “When I think of your rules from of old, I take comfort, O LORD” (v. 52); “Your statutes have been my songs in the house of my sojournings” (v. 54). Clearly this is a major theme in Psalm 119, the longest of all the psalms: “I find my delight in your commandments, which I love” (v. 47).