Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Variety Palace Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

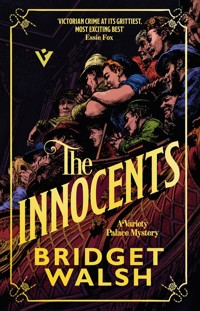

The thrilling sequel to the prize-winning historical murder mystery, The Tumbling Girl 'Historical crime fiction at its most beguiling' Financial Times 'Rich with theatrical detail and brimming with brilliant characters, this is a series not to be missed' S.J. Bennett, author of Murder Most Royal 'Victorian crime at its grittiest, most exciting best' Essie Fox Still reeling from the gruesome murders of the previous year, Minnie Ward is appointed manager of the Variety Palace. Times are hard, with performers shunning the 'cursed' music hall, and Minnie's relationship with detective Albert Easterbrook is more complicated than ever. But when another killer begins to terrorise the city's streets, Minnie and Albert are thrown together once more. The crimes seem connected to a notorious tragedy that left nearly two hundred dead-and with so many lives affected by the incident, practically everyone is a suspect...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 407

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

‘Walsh, who clearly knows her Victorians, writes with gusto… Time past is so vividly evoked that one can almost smell it. Highly recommended’

Laura Wilson, Guardian

‘Triumphant… Vivid period detail, clever plotting, and thoughtful characterizations. This series merits a long run’

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

‘Another entertaining, well-researched historical mystery… As before, the working people behind the scenes at the music hall are the stars’

Library Journal (starred review)

‘From the first dramatic and heart-breaking pages to the breathless final scenes, The Innocents is superb. Victorian crime at its exciting and grittiest best. Don’t miss it’

Essie Fox, author of The Fascination

‘A dramatic return to the music hall, as Minnie does it again. Rich with theatrical detail and brimming with brilliant characters, this is a series not to be missed’ ii

S.J. Bennett, author of Murder Most Royal

‘Bridget Walsh does it again. The Innocents is pacy, captivating and accomplished and I loved it… More Minnie and Albert, please’

Emma Styles, author of NoCountryforGirls

‘Once again, Bridget Walsh has pulled it off! She runs her writing through with such warmth and humour that it almost glows on the page. I am undecided whether I am in love with Minnie or whether I want to be her. Both, probably!’

Julia Crouch, author of The Daughters

‘A rollicking good yarn, full of fantastic and fantastical characters plus a real dash of magic’

Barbara Nadel, author of the Inspector Ikmen Mysteries

‘Richly redolent of the world of Victorian musical theatre, TheInnocentsis a twisty, turny, hugely entertaining mystery that will keep you guessing to the end’

Mark Wightman, author of Waking the Tigeriii

iv

v

vii

For Micky

viii

ix

Love is like a tree: it grows by itself, roots itself deeply in our being and continues to flourish over a heart in ruin. The inexplicable fact is that the blinder it is, the more tenacious it is. It is never stronger than when it is completely unreasonable

victor hugo

x

CONTENTS

TRAFALGAR THEATRE, LONDON

12 DECEMBER 1863

‘Cram them in,’ Taylor had said. ‘Every one of them kids is money in our pockets.’ But Freddy Graham was worried. There were so many, for a start-off. By his reckoning, at least a couple of thousand, squashed in together, sharing seats, little ones on older ones’ laps. And precious few adults to take care of them. The youngest weren’t much more than babes in arms, the oldest maybe ten or twelve. The worst age, in Freddy’s opinion. Too young to be responsible, but old enough to make serious trouble. There were a handful of the bigger lads now, up in the gallery, leaning over the rails and spitting on the kids down below. Little bastards.

He was only the stage manager. It weren’t his job to worry about front of house. He certainly wasn’t paid enough. And maybe he needn’t have bothered. The show was going well, after all, although most of it didn’t make much sense to him. It was the first time they’d staged a pantomime, and he wouldn’t be too concerned if it was the last. That scene where the King had fallen on the baby and squashed it, and then the Nurse had inserted a bellows in its arse and brought it back to life. Load of old nonsense in his opinion. The kids lapped it up, mind.

To give them their due, Williams and his crew all knew what they were about. They’d performed this show a hundred times, 2at least. And they were good. The children loved the ghost illusions, the talking waxworks. Although, to Freddy’s mind, the pantomime story seemed like a poor excuse to sling together a load of acts that didn’t really belong on one billing. Give him a nice melodrama any day. You knew where you were with a melodrama. Pantomime was just nonsense. Why have a conjurer at a baby’s christening? From his position in the wings, Freddy could see all the wires and ropes, the secret pockets, the suspicious-looking boxes that were just a little too large, or just a little too deep. But from a distance, down in the stalls, up in the galleries, it must have really looked like magic.

He hadn’t been too pleased when they’d released those pigeons, mind. He weren’t fond of birds at the best of times, and in an enclosed space they scared the hell out of him. And guess who’d be the one clearing up after them?

He looked at his watch. Nearly five o’clock. Only a few more minutes to go. He peeked out at the audience from the wings. They were growing restless. They’d been promised presents at the end of the show. Freddy had his reservations about that. The best part of two thousand kids in the theatre, half of them up in the galleries. There was no system, no way of making sure everyone got a present. But Taylor had shrugged. Said it weren’t his business. Well, whose business is it, Freddy had thought, if it ain’t front of house? Taylor had barked at him that Williams and his troupe had made a promise, and it was up to them to figure out how that happened.

‘And now, ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls,’ Williams said, his commanding voice reaching across the packed auditorium, ‘Sleeping Beauty has been restored to life. Evil has been vanquished. Good has been rewarded. We have come to the close of our magical entertainment.’

Excited cries erupted across the theatre. Poor little buggers. From the looks of most of them, there were precious few treats in their lives. And this would only be some bit of old tat: sweets, 3most likely. Maybe a whistle or a cheap doll that would fall apart before the child got home.

Williams smiled, throwing his arms wide in a munificent gesture. ‘I believe you know what time it is. It’s present time!’

Shrieks exploded from all around the auditorium. The older kids started stamping their feet. Christ, Freddy thought, they’ll start chucking up in a minute, they’re that excited. As if on cue, a little girl two rows from the stage leaned to one side and vomited in the aisle.

Freddy swore under his breath, turned away and nipped down the short flight of steps to the cupboard where he kept all his supplies. His hand reached instinctively for the bucket and mop, but found only empty air. Some bugger had been in there, taking his stuff, not putting it back. Swearing again, louder this time, he headed down the corridor and found the bucket nestled under a rail of costumes, the mop upended next to it. There were a few inches of dirty water in the bucket; enough to clear up the sick. Freddy was mentally rehearsing his complaint to Taylor when he heard a noise.

Something wasn’t right. A great disgruntled roar from somewhere out front.

Freddy made his way back into the auditorium. Williams was randomly scattering small items into the audience, the other performers lending a hand. Children leapt across each other, hurling themselves in front of the sweets, grasping for them. The bigger kids, the boys mainly, were getting most of the bounty, grabbing and pushing smaller kids out of the way.

Freddy frowned, glanced around him. Williams and his crew were only throwing stuff into the stalls. How were they gonna get anything up into the gods? Freddy looked upwards and realised what the noise was. The children crammed in the galleries had noticed they were missing out and were heading for the staircase leading down to the stalls.

Even from a distance, Freddy could see they had a feral look 4about them. This could mean trouble, particularly from those bigger lads who were leading the way. He dropped his bucket and mop, gestured frantically to the ushers nearest the stage, but they were paying no attention, too busy trying to control the mayhem down in the stalls. Freddy looked behind him. Where was Taylor when you needed him? Or anyone?

The kids in the stalls were shrieking with delight, flinging themselves in all directions to grab the bits of nonsense. Freddy caught Williams’s eye, made a gesture for him to stop, but the actor just shrugged and carried on.

Another sound started to emerge underneath the screams of delight. More shouting, but different this time. Urgent. Desperate. It was coming from the stairwell. And then he realised, with a sickening lurch, that the door into the stalls was still bolted. A long bolt at the bottom that slid into a hole in the floor. Once bolted, a gap of exactly twenty-two inches was left. They’d measured it carefully, room enough to ensure only one person could get through at a time. The usher could check their tickets before letting the next one in.

Twenty-two inches. And maybe a thousand children trying to force their way through.

Freddy stumbled forward, tripped over and staggered down the aisle, only just managing to right himself. Some older kids laughed and jeered. Any other time he’d have given them a clip round the ear, but he needed to get to that bolt.

He ran, his breath coming in gasps, his lungs burning. No one else even seemed to have noticed. Two ushers were lounging on seats at the rear of the stalls, chatting. He shouted at them, gestured towards the door, but they laughed, mockingly cupped a hand behind an ear to show they couldn’t hear him, or didn’t want to, and turned away. They never bloody took him seriously. He shouted again, but his voice was lost in the shrieks and squeals and screams. How had no one else noticed the screams? 5

By the time he got there, a child had become wedged in the doorway, then another, and another. One on top of the other until they reached almost to the top of the doorframe. He bent down to the bolt and grasped the handle. Tried to wriggle and wrench it free. It was always a bit sticky; usually he had the knack but his hands were sweating and he couldn’t shift it. He tried again, pulling desperately at the top of the bolt. It wouldn’t budge. And then it dawned on him. It had bent from the weight pressed against the door. There was no way of pulling it free. The weight of one child, even half a dozen children, couldn’t have bent the bolt. So how many were there behind the door?

Freddy reached up and tried to pull one of the children out from the top of the pile. But they were so tightly wedged in. He was afraid to drag at them, pull harder, for fear of breaking their little arms or legs. Were some of them already dead? He’d lived long enough to know what death looked like, the blank eyes, the lips parted as if to speak. But they couldn’t be, surely? Fleetingly, pointlessly, he remembered the scene with the Nurse and the bellows.

Freddy couldn’t see past the wall of bodies in front of him, couldn’t tell for sure what was happening to the other children in the stairwell. But he could hear them. Children crying for help. For their mothers. And, above his head, the sound of hundreds of little feet clattering down the stairs. They were still coming. Three flights of stairs there were. Seven feet wide. He couldn’t think why he was remembering all these numbers now. The stairs turned onto landings, so that all those who were thundering downstairs couldn’t see what lay ahead. Until it was too late to turn back.

He felt a change in the auditorium behind him. Williams and the other performers had noticed something was amiss and had stopped dispensing gifts. Then Taylor appeared from somewhere, and the ushers were behind Freddy, clawing desperately at the children. 6

‘Take them from the top,’ Freddy shouted. ‘You’ve got more of a chance of getting them out. Pull them from the top.’

But no one was listening. There was just a frenzy of arms, hands, trying frantically to pull someone, anyone to freedom. Grasping for any child they could reach.

Freddy moved away from the crowd of helpers, grabbed Taylor and gestured towards the west staircase. They usually kept it locked. Easier to control the crowd, Taylor said, if they only came through one doorway. Easier to stop anyone slipping in who hadn’t paid. Freddy fumbled in his pocket for his keys, found the one he needed, and unlocked the door. He raced up the stairs, Taylor wheezing behind him, then across the walkway linking the two staircases. Children were still pouring out of the gallery, heading towards disaster. Christ, would they never stop coming! Freddy ran past them, pushing them out of the way. He blocked their entrance to the east staircase and pointed them back towards Taylor.

Then he carried on across the walkway to the other staircase and looked down.

Freddy wasn’t a churchgoing man. He’d given all of that up years ago when a pastor assured him he was heading straight for hell. So he wondered if maybe he was already dead, because what greeted him was surely worse than any vision of hell he’d heard about at Sunday school. A sea of arms, legs, heads. Fingers grasping the air but no longer moving. Tiny mouths held open, emitting one last silent scream. Lips parted for a final desperate intake of breath that came too late. He stood for a moment, overwhelmed, not knowing where to start. They were dead. All dead.

Then he heard his own name. ‘Mr Graham? Please, Mr Graham.’

The voice was familiar. He followed the sound and glimpsed a twist of red hair peeping out from a pile of bodies. 7

His neighbour’s child. Six years old. She’d broken her ankle a fortnight ago, jumping off a wall, and had been walking with a crutch ever since. How had she survived? And what was her name? For the life of him, he couldn’t remember it.

Freddy lunged towards her. ‘I’m here,’ he said. ‘I’m coming. Hold on.’

He stumbled forward, felt something soft beneath him. He looked down. An arm, the child no more than four or five. He couldn’t see if it was a boy or a girl. He moved forward more tentatively, trying to avoid stepping on anyone. Then realised the pointlessness, and ploughed on, telling himself not to dwell on what lay beneath his feet, but only what lay ahead of him. A living child calling his name. There were bodies piled high around her, and he lifted them, pushed them aside, not allowing himself to think about what he was doing. How each of these bodies was somebody’s daughter. Somebody’s son.

He reached her. She was tucked into a corner of the landing. Her crutch had somehow got wedged in front of her and acted as a barrier. It had given her just enough space to breathe. He reached behind the crutch and lifted her out, cradling her head in his hand, her hair soft and fine as thistledown, her little heart thumping in her chest.

Holding her tightly, murmuring words of comfort all the while, he staggered back along the walkway, down the west staircase and carried her outside. He sat her down carefully on the pavement. There were other children, standing or sitting, moving aimlessly or not at all. It was raining, but no one seemed to have noticed. They huddled together instinctively, staring blankly into the distance, or reaching blindly for a hand to hold. Toys lay discarded on the ground. An older girl who seemed to know his neighbour’s child pulled her close. Freddy still couldn’t remember the little girl’s name.

He turned back. He had to rescue whoever he could. And some 8of them – lots of them, surely – were still alive. If they were making noise, they were alive.

Later, when they had finally freed all the bodies and laid them out in lines on the pavement, Freddy walked up and down the rows and counted them. He had to do it twice, because he figured he must have got it wrong the first time. But he hadn’t.

One hundred and eighty-three of them. One hundred and eighty-three kids who weren’t going home.

He walked back into the empty theatre. The air was thick with the sharp tang of piss; so many of the poor mites had wet themselves in fear or desperation. All down the stairwell were little caps and bonnets, torn from heads and trampled underfoot. Buttons with lengths of thread attached. The sole of a little boy’s boot torn from the uppers. A red hair ribbon ripped from a girl’s head. A hank of blonde hair with blood at the roots.

ONE

NOVEMBER 1877

She wasn’t their usual bookkeeper; he had six months left to serve if he kept his nose clean. This new woman – Mrs Dorothy Lawrence – was younger than Minnie had expected, somewhere in her twenties, maybe thirties, with a pleasant, open face, and rather beautiful hair which she wore elaborately dressed. Minnie peered more closely; if any of it was false hair, it must be the expensive stuff, ’cos it looked like it was all her own. She wore what seemed a simple, almost severe dark-navy dress. But Minnie could see it was cut perfectly to highlight her impressive figure. There wasn’t a straight line about her. She was all curves and magnificent hair. She belonged on the wall of a fancy art gallery.

Mrs Lawrence hadn’t shown any surprise that a woman could manage a music hall, which made a nice change. Now they’d spent twenty minutes in total silence as she’d looked over the books, wincing on occasion and peering at Minnie over her glasses before resuming her perusal.

‘Before you took up the reins, the Variety Palace was thriving under Mr –’ she said, glancing down at the papers, ‘Mr Edward Tansford. Why is he no longer in control? He is still the co-owner, I take it?’ 10

‘Mr Tansford was deeply affected by the tragic events of last year. He’s finding it difficult to return to work.’

‘Well, I would suggest he overcomes any emotional compunction and gets himself back to the Variety Palace quick smart.’

Emotional compunction, Minnie thought. Unbidden, an image flashed into her mind. Blood. A life leaching away before her eyes. Tansie’s cry. She bit her tongue. Right now, she needed this woman’s help. Once they were back on their feet she’d tell her what she could do with her emotional compunction.

Mrs Lawrence looked again at the papers. ‘You appear to have been haemorrhaging performers over the last few months. Any reason?’

‘They’re a superstitious lot, theatrical types. Some of them started to say the Palace was cursed. What with the murders and all.’

The other woman blinked slowly, then measured her words as if each of them was worth a shilling. ‘Murders? In the plural? How many are we talking about, Miss Ward?’

‘Three. Well, more actually, but three people who worked at the Palace were murdered.’

‘I see. Numbers like that might render the most confirmed sceptic a trifle superstitious. And these murders, they were solved?’

‘Oh, yes. We caught the killers.’

‘We?’

‘Me and a private detective. Albert Easterbrook.’

Mrs Lawrence frowned. Then sighed. ‘But you are not a private detective, Miss Ward?’

‘No. I’m a writer. For the Palace and a few other places, but mainly the Palace. And now I’m managing it. In Tansie’s – Mr Tansford’s absence. It’s complicated, I’ll give you that. But all you really need to worry about is the profit and loss.’ She nodded at the tattered notebook and bundle of papers on the desk.

Mrs Lawrence extended an elegant finger and tentatively 11touched the bundle, as if afraid of infection by association. ‘Judging by this, it would be correct to assume that bookkeeping isn’t one of your many talents.’

‘No,’ Minnie said, forcing herself to remain calm as her lips stretched to a thin smile. ‘In between writing enough to keep the wolf from the door, taking on a management role I ain’t suited to, and helping to solve the murder of my best friend, I ain’t had time for much else. I thought bookkeeping was what I’m paying you for.’

The other woman gave her a hard stare, and then started to explain – at great length – exactly where the problem lay.

‘Impending doom.’ The words hadn’t actually been used, to be fair, but that was how it felt to Minnie. Mrs Lawrence had definitely said ‘deficit’, ‘closure’ and ‘trouble’. The bottom line was they needed to pull in more punters, or the Variety Palace could be out of business before Easter.

She scurried through the back streets to the Strand, lowering her head against the chilly November winds, and ticking off everything she’d done that morning, alongside her painful hour with the bookkeeper: pacified the butcher who was waiting for his payment; hurried along the carpenters who’d been hired to produce a dozen hinged scenery flats, and so far had produced only two; nipped into the Gaiety and unsuccessfully tried to persuade Gertie Steadman, the juggling fire-eater, to do a turn at the Palace. Longingly, she thought of the days when all she’d had to do was knock out a few songs and sketches.

Pulling the stage door of the Palace behind her, she narrowly avoided colliding with Betty Gilbert in the cramped corridor. It was only twenty minutes to the matinee and, as usual, chaos reigned. Betty, dressed in form-fitting bloomers and corset for her turn as an acrobat, shouted in passing, ‘Bernard’s looking for you, Min.’ 12

Minnie sighed. If Bernard Reynolds was looking for her this close to curtain-up it couldn’t be good. Usually consigned to ‘thinking parts’, a few weeks ago Bernard had suggested a sketch where he dressed in an animal ‘skin’ and performed a song-and-dance routine. She must have had a sudden rush of blood to the head, because she’d agreed. Nothing had gone smoothly since.

She hurried down the flagstone corridor to her office, although she still thought of it as Tansie’s. Maybe she could hide there for the next twenty minutes.

No such luck. Lounging in the upholstered chair she’d installed for a little bit of comfort, with his feet firmly positioned on the desk, was Tansie. He’d regained the weight he’d lost after Cora’s death, and was slowly starting to assume some of his old flamboyance. Today’s choice of suit was a dark-green velvet which Minnie had to admit was rather smart.

‘Comfy enough?’ she barked at him. ‘Sure you wouldn’t like a little cushion? A blanket? Little tot of something while I’m up?’ He glanced up from the newspaper he was reading, refusing to rise to the bait. ‘Kippy’s looking for you,’ he said. ‘His favourite hammer’s gone missing. And there was something about the trapdoor not working again.’

‘And you couldn’t have seen to it, I suppose? Given it was your bleedin’ idea in the first place?’

Against her better judgement, Minnie had agreed to Tansie and Bernard’s ambitious plans for a star trap. It covered an opening in the stage, beneath which Bernard stood on a platform, ready for his entrance in what was ambitiously – and fraudulently – billed a magical menagerie. Kippy, the stage manager, released a counterweight, and Bernard was propelled upwards for a spectacular entrance, appearing to fly through the air. Rehearsals had not gone well.

Someone coughed gently behind Minnie. She turned to see 13Bobby, one of the stagehands, a lad of seven or eight, with a steaming mug of tea in one hand and a large pork pie in the other. He smiled at Minnie, then slid past her to place the tea and pie in front of Tansie, who nodded his thanks before breaking off the crust and feeding it to a small black-and-white monkey who sat on the desk in a miniature deckchair.

‘Oh, and Bernard’s on the warpath,’ Tansie said. ‘He’s been asking after you all morning. Been anywhere nice?’

Minnie took a deep breath and recounted her morning to Tansie in language that would have made a navvy blush, before requesting that he shift himself or she’d be inserting the pork pie and the mug of tea up a certain part of his anatomy where even his own mother wouldn’t venture.

Tansie smiled broadly, revealing the flash of a gold tooth.

‘What?’ Minnie said.

‘It’s the first bit of fire you’ve shown in months, Min. Nice to have you back.’

He sprang up from behind the desk and the three of them made their way to the stage, the monkey seated on Tansie’s shoulder eating the remains of the pie crust and shedding crumbs behind him like a furry Hansel.

From the wings, they peeped out into the auditorium, which was filling slowly. This was the bit Minnie loved, those few minutes before a performance started. It reminded her of her own first visit to a music hall, sneaking out of the house against her mother’s instructions and hiding behind some woman’s skirts so she could get in without paying. Even though she’d known she’d be clobbered when she got home, it had all been worth it when the curtain went up and she was transported into another world, where everything seemed possible.

‘You could squeeze a lot more in,’ Tansie said. ‘Few more tables and chairs. Little ones on their mothers’ laps. We could charge the bloaters extra for wear ’n’ tear.’ 14

Minnie glanced down at Tansie’s stomach. ‘We don’t charge you extra.’

Tansie shrugged. ‘What was it that accountant said? “Financial peril”, weren’t it?’

‘Which reminds me. You know what you’d be really good at, Tanse? Running this place. Like you’re supposed to.’

Tansie shook his head. ‘Too soon, Min.’

‘I understand, Tanse. Really I do. I was there, remember? But it strikes me you ain’t finding it too soon to go poking your nose in at every opportunity. So, no offence or nothing, but is there any chance you could sling your hook? You’re either here or you ain’t. You can’t be both.’

He looked affronted. ‘I’m only trying to help, Min.’

‘Well, you ain’t. All you do is come up with hare-brained ideas that cost money and don’t work. I’ve got enough to deal with, Tanse.’

‘Like what? Besides running this place? You doing much for Albert?’

‘With Albert. I worked with him, not for him. Remember?’

‘No need to get the spike,’ Tansie said. ‘I only asked.’

Minnie sighed. It was herself she was angry with, not Tansie. Her relationship with Albert Easterbrook was complicated, and not something she wanted to spend much time thinking about.

‘To answer your question, Tanse, I’m too busy here to be developing a sideline as a detective.’

Tansie looked down at his shoes, a beautiful pair of highly polished oxblood brogues. He drew invisible patterns across the flagstones of the backstage corridor with one foot. ‘You can’t hide forever, Min,’ he said quietly. ‘You need to move on.’

‘Like you have, you mean? Your best mate is a monkey, Tanse. Even you must know that ain’t normal.’

He shrugged. ‘At least I don’t spend every minute of my life inside this place.’ 15

A few months ago, Minnie had moved into two rooms tucked away behind the upper gallery. It saved a lot on rent, but it wasn’t the healthiest arrangement. Some days she never left the Palace. Once upon a time that would have bothered her.

A bell rang. The show was about to start. Quiet descended backstage, punctuated by the opening salvos of Paul Prentice, the unfunniest funny man in London, who hadn’t taken any of Minnie’s hints that maybe his music hall career was over.

Minnie slipped out of the wings and back to her office. Frances Moore, one of the dressmakers used by the Palace, was waiting for her. An unassuming-looking woman, tall, with features so fine and dainty it looked as if her face had been drawn with a very sharp pencil. The kind of woman you might pass in the street and pay no mind to. But look more closely and you’d see she had a delicate beauty about her. She was one of the best dressmakers within five miles of the Strand and insisted on being called Frances, never Fran.

Frances gestured towards a package wrapped in brown paper and tied with string on Minnie’s desk. ‘Done,’ she said. Minnie knew before she even opened the parcel that the work was going to be exquisite. And she was right. Two tiny ballgowns with billowing tulle skirts covered in sparkles that would catch the light with every movement on stage. The Fairy Sisters were going to be delighted. Unexpectedly, Minnie felt tears prick her eyes. She must be going soft in her old age.

‘They’re beautiful, Frances. You could charge us twice what you do, you know.’

‘Don’t go letting Tansie hear you saying that. Besides, I like working for the Palace. Where else could I get free tickets and all the beef sandwiches I can eat?’

Minnie ran her eye over Frances’s slender frame. ‘I’m surprised you can manage even one of those sandwiches. And all I’m saying is, you could charge a lot more for your work.’ 16

Frances shrugged. ‘I do charge more. To those that can afford it. Word has it that the Palace might be in a little – trouble?’

Minnie sighed. You couldn’t keep anything a secret on the Strand. ‘Things have slowed down a bit. It’ll pick up again.’

‘’Course it will. In the meantime, you let me know when you need anything more.’

Five minutes after Frances had taken her money and left, Minnie was hanging the two tiny dresses on the rail in the backstage corridor when she heard her name and turned to see Bernard bearing down on her. Behind him was Kippy, the two men clearly vying to see who could reach her first. Bernard was hampered by a pair of hooves on his feet but he still won.

‘I need to talk to you, Minnie,’ he said. ‘In private?’

‘I don’t know what Bernard’s latest gripe is,’ Kippy said, ‘but we need to discuss that bleedin’ star trap. It still ain’t right.’

When first installed, the platform had propelled Bernard upwards, but the trapdoor on the stage had failed to open. Bernard had been game, you had to give him that, but there were only so many blows to the head a man could take. Kippy had worked tirelessly to improve the mechanism until the trapdoor opened but Georgie Carter, who was playing the part of a zookeeper, kept forgetting where to stand and had fallen through the trapdoor with such astonishing regularity Minnie wondered if it wasn’t Georgie who’d taken the blows to the head. Endless rehearsals, and a series of chalked crosses on the stage, had finally impressed on him where not to stand. Foolishly, Minnie had thought the problem was solved.

‘It’s the propulsion on the platform,’ Kippy said. ‘There’s too much force, and I ain’t sure I know how to fix it. Bernard almost landed in the flies this morning during rehearsals.’

Laughter erupted from the audience. ‘Paul’s going down well,’ Bernard remarked, ‘given he learned most of his jokes from Moses.’ 17

‘So maybe we abandon the star trap altogether?’ Minnie suggested.

‘My sentiments exactly,’ Kippy muttered. ‘We’re a music hall, not bleedin’ Drury Lane.’

‘As if I need reminding,’ Bernard sniffed. ‘But I am not prepared to abandon the mechanism simply because we are suffering a few teething problems. Would Irving stumble at the first hurdle? Would Kemble? No. The star trap stays.’

‘So is that why you wanted to see me?’ Minnie said hopefully.

‘No. It’s a private matter. Your office?’

Paul had completed his act, and emerged backstage looking decidedly pleased with himself. Out in the auditorium Harry Gordon, Tansie’s stand-in as master of ceremonies, was regaling the audience with promises Minnie was pretty certain the next act couldn’t fulfil. Carlotta, a sheen of sweat visible on her upper lip, slid nervously past Minnie and waited for her cue from Harry.

‘Can it wait, Bernard?’ Minnie said. ‘We could have a chat after the show, if you want.’

‘Promise me you’ll make the time, Minnie. It’s important.’

She sighed. Everything was a matter of the greatest urgency with Bernard. Then it turned out to be a complaint about running order, or a mess in one of the dressing rooms, or whether he should make his entrance on the second or third bar of music.

‘I’ll make the time,’ she said. ‘Promise.’

‘I’ve been thinking, Min,’ Tansie said, sidling up behind her and making her jump.

‘I thought I could smell burning.’

‘There’s a mate of mine. Handy Mick. Reckons he could install a water tank and pump beneath the stage for a fraction of what you’d normally pay. We could have all sorts of fancy effects. Rivers, fountains, waterfalls.’

‘Is this the same Handy Mick who flooded the Star last month?’

‘It weren’t his fault that porcupine got loose.’ 18

‘You don’t think there’s a danger, if we start mucking about with rivers, fountains and waterfalls, that we’ll just end up drowning someone? Given that we don’t seem able to get a bleedin’ trapdoor to work properly?’

‘You gotta dream big, Min, if you want to achieve greatness.’

‘Well, I’d just like to achieve a single performance where no one ends up with concussion.’

As if on cue, a deafening crash from the stage made them all jump. The monkey grabbed hold of Tansie’s hair, resulting in a stream of whispered curses from Tansie. Minnie would happily have dispensed with plate spinners but Tansie was adamant the punters expected to see one. Carlotta was so inept she must be keeping the potters of Stoke-on-Trent in luxury biscuits. Luckily, the audience seemed to think it was deliberate and were whooping with delight. Minnie looked at her pocket watch. Only another hour and a half to go.

Two hours later, the Palace was blissfully quiet. The show had gone surprisingly well, the audience had departed, and most of the performers had nipped out for a quick bite before the later show. Minnie settled herself back in her comfy chair and removed a small card from her purse. ‘Ward and Easterbrook,’ it said. ‘Consulting Detectives.’ She ran her finger across the surface, remembering Albert’s joke about not being able to stretch to vellum. She’d been carrying the card around since the day he’d given it to her, removing it from her purse every now and then to gaze at the words and think about how different things might have been.

She had promised to help him. But every time he appeared, needing her help with a missing pet, a cheating husband, a stolen item of jewellery, she had told him she was too busy at the Palace. Which was true, but still. Lately, he hadn’t been coming around 19so much. It was probably for the best. Every time she saw him she felt herself slipping back into a world she had spent the last nine months escaping from.

But she missed him. Particularly at times like this, when she was so tired she felt like she was melting at the edges. Or when she felt completely alone, even though she was surrounded by people. What she wouldn’t give to have him close by. To lean into him. She had done that once. He had smelt of clean sheets, and she had wanted to stay there.

She held the card gently between her finger and thumb for a moment, then opened a desk drawer and dropped it in among the pencils, old song sheets and other detritus.

A gentle knock at the door roused her. Bernard stood in the doorway, his costume swopped for a brown serge suit, although he had not been entirely successful in removing the last traces of his stage make-up. The whiff that wafted across the room told Minnie he had reapplied his goose-grease pomade to the remaining strands of hair he meticulously combed over his pate.

‘A moment of your time, dearest one?’

Minnie nodded and gestured towards a chair.

‘It concerns my brother, Peter. He’s on the missing list. We meet every Wednesday for an early supper between the matinee and evening performances. He didn’t appear last week.’

‘So something came up. That German fella – Otto something, weren’t it? – is he back in town?’

Bernard shook his head firmly. ‘Our Wednesday meetings are sacrosanct. No matter what the distractions, Peter is always there.’

‘You been to his digs? His place of work?’

‘His landlady hasn’t seen him in nearly a week. He’s been working at the Fortune, but they’re dark at the moment. Refurbishment. I tracked down one or two of his chums, and they haven’t seen hide nor hair of him since Tuesday, when the Fortune closed.’ He paused, playing with a gold signet ring on his little 20finger, the entwined initials of his parents engraved on the surface. He seemed uncertain of how to go on; Bernard was never normally lost for words. ‘This isn’t like him, Minnie. Not at all like him.’

‘I’m really sorry, Bernard, but I ain’t doing any more detective work.’

‘Of course, of course. I was just wondering if you could speak to Albert about it. Perhaps he could exert some influence with that police officer friend of his? I’ve reported Peter as missing, but the officer I spoke to seemed somewhat indifferent. I thought – perhaps – with your connections, you might be able to pull some strings.’

‘Why not have a word with Albert yourself?’ Minnie asked.

He shook his head. ‘I barely know him, dear heart. It wouldn’t take up much of your time, surely?’

‘I’ll ask. But I can’t promise he’ll do anything with it. He’s very busy these days, you know.’

‘Thank you,’ Bernard said. She waited for the Shakespearean quotation or the anecdote from his glittering acting career. But there was nothing. He simply gave her a gentle smile and left.

She sat for a few moments, questioning why she felt so reluctant to speak to Albert. It was purely business, after all. Simply asking a favour for a friend. She could be in and out of there in no time. Hardening her resolve, she rose, grabbed her bonnet and coat from the back of the door and made her way out into the chilly November evening.

TWO

Albert Easterbrook removed his hat and loosened his tie. He was glad to be home. The church had been bitterly cold, the graveyard even colder, an easterly wind whipping at the mourners’ ankles and making everyone huddle inside coats and scarves. But it had gone well, if such a thing could ever be said of a funeral. Now the real mourning would begin, when he would need to come to terms with his loss and all it meant.

‘Tea, Albert? Inspector Price?’ Mrs Byrne said, nodding towards John, Albert’s friend and former colleague. ‘Or something stronger?’

Albert nodded at the drinks cabinet. ‘Would you join us, Mrs B?’

‘I won’t if you don’t mind. Funerals always exhaust me. If I have even a sniff of brandy I’m likely to fall asleep, and I’ve still got tonight’s supper to prepare. Nice chicken, I thought. And maybe a lemon posset for pudding, if Tom remembers to bring me back some lemons from the greengrocer’s. I’ll leave you to it.’

Albert and John seated themselves by the fire, each nursing a large glass of brandy. The cold seemed to have permeated Albert’s bones, and he dragged his chair closer to the hearth.

‘A good send-off, Albert,’ John said tentatively.

Albert nodded. ‘It was kind of you to come. Particularly as you never even knew her. Work is busy as ever, I imagine.’ 22

John shrugged. ‘You know how it is, Albert. Always busy, just some times not quite as bad as others.’

‘The Hairpin Killer seems to have gone quiet,’ Albert said, grateful to talk of something other than the morning’s events.

The Hairpin Killer had stalked the streets of London for the last decade, preying on young women and murdering them with a knife to the thigh and then inserting seven hairpins into their hearts. Hence his moniker.

‘Quiet for now,’ John said. ‘He’s done this before, mind. Lain low for a while and then re-emerged.’

‘In prison, do you think?’

John nodded as if the idea wasn’t a new one. ‘That’s my theory. I reckon he gets nicked for something minor, spends a few months inside, then he’s back out again.’

The two men peered down at their drinks and John shifted in his seat. ‘Your father—’ he said, then winced as if his thoughts caused him discomfort.

‘You can’t think worse of him than I do, John. I learned long ago that he has a heart of flint.’

‘Did he speak to you at all?’

Albert shook his head. ‘Not even today. At my own mother’s funeral. I’ve no doubt he’s feeling her loss, but he couldn’t bring himself to offer a word of greeting or condolence. Just walked away when I tried to approach him.’

‘I liked your sister,’ John said. ‘Kind of her to take the time to speak to me, particularly when she was taking it so hard. But that husband of hers—’ He broke off again, not needing to complete the sentence. Albert had little time for his brother-in-law, Monty Banister, and had never made any secret of his feelings. The man was a pompous, self-serving ass. And that was on a good day.

They sipped their drinks, enjoying the fact that neither of them felt the need to speak. The quiet was broken by Mrs Byrne 23re-entering the room to hand Albert a small parcel. ‘It came while we were out,’ she said.

Albert read the card: ‘A token of my gratitude – Lord Ballantyne’. He unwrapped the parcel and held out the item to John, who turned it slowly in his hand.

‘Are those real?’ John asked.

‘Oh, yes. Although what Lord Ballantyne imagines I’m going to do with a diamond-encrusted snuffbox is anybody’s guess.’

‘Well, your investigation did save his only daughter from running off with that dodgy fella with the dicky eye. Although something a little more practical might have been handier. You could always flog it, I suppose. Work’s going well, I take it?’

Albert felt relieved to be on the safer ground of his detective agency, rather than discussing his uncomfortable relations with his family. ‘Almost too well. I’m having to turn cases away. I’ve hired Tom Neville – that lad who worked for Lionel Winter, remember? Which reminds me. Any sign of Tom, Mrs B?’

‘He was here when we got back, and then he heard me muttering about lemons and he decided I was also running low on tea so he’s popped out again. Can’t stand funerals, that lad. When he saw me in my mourning dress he went a very strange shade of green. I expect he’ll be back in an hour or so.’

‘Is that young lady at Fletcher’s still sweet on him?’

Mrs Byrne nodded. ‘And he’s too soft-hearted to tell her no. Still, I imagine it takes his mind off Daisy, if only for a while. God rest her soul.’

She closed the door behind her. John lit a cigarette, offering one to Albert, who declined. Although surely, today of all days, Mrs Byrne could have no objection.

‘Been working on anything interesting?’ John asked. ‘Anything that would explain why I ain’t seen you in the ring for weeks?’

Albert winced. He and John had been regular sparring partners 24for several years now, but Albert knew he was guilty of sometimes allowing work to take precedence over friendship and boxing.

‘Next week, I promise,’ he said. ‘And yes, I have had an interesting case. Or a puzzling one, at least. Client came to see me about her husband’s death. William Fowler. He was found hanged. His wife thought it was suspicious and she said there was never any hint he’d been suicidal. I’ve looked into it, but it’s the old problem: I came too late. Didn’t see the body when it was first found, and the man was buried before his widow even thought to speak to someone about it. There’s nothing to suggest foul play. But also nothing to suggest he was unhappy enough to take his own life.’

There was a knock at the front door. A few moments later, Mrs Byrne entered, a smile playing at the corners of her mouth. In her wake was Minnie, removing her hat and coat as she came in.

‘Well, if it ain’t Inspector Price,’ Minnie said.

John grinned and looked mildly embarrassed. His promotion was still very new.

She turned to Albert, took in his mourning suit, noticed his hat on the table, the black band encircling it.

‘Who’s died?’ she asked.

‘My mother.’

Her face softened and she reached forward to take his hand. ‘Oh, Albert, I’m so sorry. Was it sudden?’

‘A short illness,’ Albert said, struggling to keep his voice under control. Minnie’s obvious sympathy had released an unexpected wave of emotion.

‘And the funeral?’ she asked.

‘It was this morning.’

Minnie frowned, pulled back from him. ‘This morning? Why am I only hearing about it now?’

Albert shrugged. ‘You didn’t know her, Minnie.’

‘Neither did John, but by the looks of his suit he’s come from 25the same place as you. Besides, I might not have known your ma, but I know you, Albert. You should have told me.’

It had been his first thought on hearing of his mother’s death – to tell Minnie. And then he had reminded himself of how cold she was with him these days, pushing him away, refusing to help with the business, although she had promised she would. What were they now to each other, other than two people who had once worked together, once dreamed of something more. He wanted to tell her this, but what was the point?

‘You’re so busy these days, Minnie. I didn’t want to trouble you.’

Her frown deepened. He knew the truth of his words had hit home, but she would never admit it. ‘I ain’t so busy I wouldn’t have time to pay my respects, offer some comfort. And you know that, Albert. So don’t go putting it all on me.’

An uncomfortable silence descended on them for a few moments, then Minnie continued. ‘Anyway, I didn’t come here for a barney, Albert. I need to ask you something. A favour.’

‘Anything,’ he said. ‘You know that.’

‘It’s Bernard. Or, rather, his brother.’ She outlined what she knew of Peter Reynolds’s disappearance.

‘Has he done anything like this before?’ Albert asked.

‘Not according to Bernard. He’s really worried, Albert, or I wouldn’t ask.’

‘Tell him I’ll look into it, of course I will. Top priority,’ Albert said, trying to assuage his guilt for the pain he’d caused her.

‘And me,’ John chipped in. ‘Can’t hurt, can it?’

Minnie gave them both a thankful look and then turned away. Her eyes darted round the room, lighting on the snuffbox John had left on the mantelpiece.

She walked across, picked it up and traced a finger over the jewels before holding it up to the light for a closer look.

‘Very la-di-da. Surprised you can find time for the likes of me and John these days.’ 26

‘It’s because of you I have clients like that, Minnie.’

A shadow crossed her face. So fleeting most people would have missed it. Albert didn’t. He knew Minnie struggled with any mention of the previous year’s events.

‘Take it,’ he said, as she placed the trinket back on the mantelpiece.

She shook her head, the slightest smile flickering across her lips. ‘I’ve been trying to give up the snuff. Plays havoc with the old nasal passages.’

Albert smiled and the mood lightened between them.