Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

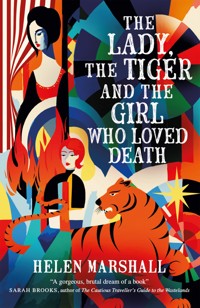

A young woman is seduced by the glamour of the circus and drawn into a dangerous world of violence, cruelty and revenge. For readers of Erin Morgenstern's The Night Circus and Helen Oyeyemi's Mr Fox. A dark fantasy tale infused with mystery and threat from the award-winning author whose work has been described by Paul Tremblay as "intelligent, dark, wildly inventive" As Sara Sidorova hovers between life and death, she is visited by Amba, the tiger god who will devour creation if he is released from the chains that bind him. Amba gives Sara an extraordinary gift: a glimpse into the future. Years later, her granddaughter Irenda will grow up in a war-torn country where survival means obedience. When a devastating attack robs her of her parents, she travels to Hrana City. There, her grandmother agrees to teach her the ultimate secret: how to tame death. In the circus, amongst the magicians, the strongmen and the contortionists, she will start down a dangerous road, to carry out a revenge decades in the making... and bring justice into the world for herself and for her family. Rich with glamour and strangeness, brutality and deceit and the dark magic of the circus, this haunting fable from a multi award-winning author will chill your bones and make your heart ache.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 493

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Contents

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

In the Beginning

1

And in the Beginning

2

Daybreak

3

The Evening Star

4

5

Morning

6

The Granddaughter

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Midday

15

The Beast Girl

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Afternoon

29

Lady Pale-Throat

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

Evening

48

The Mirabilist

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

Twilight

65

66

The Morning Star

67

68

In the End

69

And in the Beginning

70

Acknowledgements

About the Author

PRAISE FOR

The Lady, the Tigerand the Girl Who Loved Death

“This is a gorgeous, brutal dream of a book. It asks questions about power and belief, about time and magic and love, and every sentence pulses with danger and beauty. It will haunt me for a long time. I implore you all to lose yourself in its strange enchantments.”

SARAH BROOKS, bestselling author of The Cautious Traveller’s Guide to the Wastelands

“Extraordinary. Helen Marshall channels the best of Angela Carter then takes it up a notch or three. A gloriously bewitching new tale from one of our best fabulists.”

ANGELA “A. G.” SLATTER, award-winning author of The Briar Book of the Dead

“The Lady, the Tiger and the Girl Who Loved Death blew my mind, and forever changed how I looked at writing. Haunting and soaring, transcendent, and masterfully executed – Helen Marshall’s talent is unparalleled.”

TASHAN MEHTA, author of Mad Sisters of Esi

“Lyrical, beautiful and brilliant, The Lady, the Tiger and the Girl Who Loved Death is a magic puzzle box that surprises and delights with every revelation.”

KAARON WARREN, author of The Underhistory

“Chillingly beautiful, with wonder and dread in every word. Fans of Pan’s Labyrinth, The Night Circus and The Cautious Traveller’s Guide to the Wastelands should be first in line for the big-top spectacle of Marshall’s lyrical storytelling and wild imagination.”

CHRIS AND JEN SUGDEN, authors of High Vaultage

“It is a rare story which manages to be thoughtful and colourful at once. Angela Carter did that, and now Helen Marshall does it in her own way. A book which you can’t stop reading, and then you can’t stop thinking about.”

FRANCESCO DIMITRI, author of The Dark Side of the Sky

“Helen Marshall’s writing is, as ever, mesmerising. She has a vivid, keen-eyed vision of the past and its possibilities, of hope and hatred, of cold realities and dark dreams colliding. This is a sensuous, spellbinding read.”

ALIYA WHITELEY

“Gilded in bone-dust, with the breath of a predator, Marshall’s The Lady, the Tiger and the Girl Who Loved Death is a pageant of the masks myths and politics alike wear as they pace their cages, and the bloody chains that bind them.”

KATHLEEN JENNINGS, author of Honeyeater

Also by Helen Marshall

THE MIGRATION

THE GOLD LEAF EXECUTIONS

GIFTS FOR THE ONE WHO COMES AFTER

HAIR SIDE, FLESH SIDE

SKELETON LEAVES

THE SEX LIVES OF MONSTERS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Lady, the Tiger and the Girl Who Loved Death

Print edition ISBN: 9781803369518

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835413609

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: June 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Helen Marshall 2025

Helen Marshall asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)

eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, Estonia

[email protected], +3375690241

Typset in Fournier MT Std & Esmerelda Pro.

To Vince Haig and Malcolm Devlin.The Twins.

1

There is light. At least that’s how the story goes, isn’t it, my love?”

2

The girl follows the road past the hidden sunflowers. It was her husband who showed them to her, a field of dry earth that would blossom like cloth-of-gold in the height of summer. Dead now, he must be, though she hasn’t seen his body. Her name is Sara Sidorova; she is eighteen years old and a widow already.

Days pass as she searches the wildwood for his remains. She marks the hours as the sun rises in glory, then sets in a blue gloom. Birch and alder line the dusty track that brought her this way. Skeleton trunks. Alder is good for sleeping, she knows. Feliks taught her that. Before they were married, they’d lie beneath an alder as high as a steeple, listening to waxwings and bluethroats. Now she cares only for the shriek of the mourning birds, her guides in this terrible business.

She knows these woods well, all this beautiful, terrible sliver land. Mountains in the west, the impassable spine between this little world and the next. The lakes, the coastland, wild and dark, the plains, then the forest, the killing zone, and beyond it the border. Nothing here is easy. In Strana, her people say: We are small but we will make you bleed. We are the bone that will choke you if you try to swallow us. Her people say: We are invaded but it will cost you to take us.

Strana. Country.

If this thrice-tenth nation had another name once they have forgotten it as they have forgotten so many things.

She stumbles on, her clothes shredding to rags, her feet bloody, her painted nails gone wretched as talons. On the fifth day she discovers a body in the woods—not her husband. This one is too old, over forty. Tawny hair, thinning near the crown. Big shoulders, a big man. The hole in his woolen gymnasterka seems smaller than a thimble. She could dig out the bullet if she wished, but he is only so much meat now.

Still, needs must.

Sara Sidorova takes the dead man’s knife, misshapen from over-sharpening. His boots, which are too large. A week ago Captain Olender asked her to dance. Once she loved dancing. She knows she will never dance in these stolen boots, even as she hacks strips from the dead man’s uniform and stuffs the rags in her toes.

“‘Juniper, juniper, juniper, my juniper,’” she sings as she goes about her work. “‘Under the green pine, lay me down to sleep.’”

Then in the distance—the livid shadows of others approaching: a legion of soldiers. The dead man’s friends? His murderers? They all wear the same jackets, speak the same language, so how could she know? Sara Sidorova vanishes beyond the treeline.

Her grandmother told her a story about the devils in these woods who turn men into smoke. Remembering it, she fits herself between birches bleak as old houses—invisible. She doesn’t know these soldiers but she hates them anyway. She never knew hate before, but now it’s an animal inside her.

Storm clouds gather, drench the earth, and then retreat. Afterward, Sara Sidorova trails the legion with nothing but the knife in her hands. She could slit their throats while they slept in the mud if they weren’t so watchful—but they are watchful. And for all the days she has spent learning to hold herself straight, learning never to bend, still she is too weak.

At night, she howls her grief. The soldiers huddle round their campfires, blowing warmth into their hands, pretending it’s the damp that has prickled their skin.

“Listen, do you hear that?” says one. Local accent. He is sixteen, maybe. Younger than her and certainly younger than the others. A stripling with a mop of pale blond hair and a delicate, pointed chin.

“It’s nothing. The wind.”

“Listen, I said! There’s a tiger in these woods. A man-eater. I heard it tore through a camp not far from here. Gorged itself on the captain and ate everything but his heart.”

The boy is canny but all they see is a coward. Perhaps they’ll kill him on their own.

“Something is out there,” he says again.

The old reflex: “What kind of man are you then? Are you afraid?”

Soothsayer, prorok, elf-child. Sara Sidorova doesn’t expect anyone will listen to him.

This time she is wrong. Their commander doubles the guard and no one sleeps that night. In the morning they muck out pits and whittle birch spears to lay inside. One among them knows how to hunt a tiger.

The girl’s stolen knife isn’t sharp enough, her body isn’t light enough. She still leaves too many tracks. She abandons them for a time to hunt for cloudberries and the tender shoots of cornflowers. She chances the mushrooms with their delicate fringed veils and wonders whether she might poison herself. If it would matter. What is she living for anyway?

The baby kicks. Her name will be Else, if it’s a girl. If it’s a boy she will have to strangle him.

She hushes her hate. Back to the road.

* * *

It’s close to dawn when she makes her second mistake.

All around her, the wildwood is alive, first with warblers and rose-finches, then the rest of the noisy lot. Sara Sidorova moves through the undergrowth, letting the birdsong hide her business. But she isn’t as silent as she thinks. Suddenly, a bullet slams into her shoulder. The crack like thunder comes too late in warning.

She falls in a slow spiral. No pain, not yet.

Was this how it happened, husband? she wonders. Is this how they killed you?

Then there’s wet loam beneath her, sweet smelling. She wants to stay, sleep in her pain now death has come. She puts her thumb to the wound. Her blood is coming out in spurts, and, with it, her fury and helplessness.

The soldier boy’s face hovers over her: pointed chin, fey-blue eyes. “I thought you were one of them!”

Sara Sidorova doesn’t believe him. After all, she’s wearing the same jacket he is.

“You’re just a girl,” he says though she is older than he is. At eighteen strands of bone-white gleam in the tawny thicket of her hair.

“I’m sorry,” he mutters, staring at the knife.

“Go away!”

“If I do, you’ll die. Gangrene or blood sickness. I’ve seen it before. Why are you so dirty? Why are you so thin?”

Scarlet smears across his cheek as he tries to wrestle her up. Her belly is cramping, a deep, bleary pain that tightens and loosens. The child mustn’t come yet. Too soon.

“Leave me alone!” she hisses, for above all, she doesn’t want him to see the bulge beneath the jacket.

“I’ll take you with me.”

Now she is fumbling with the blade. She can’t work her right arm properly but all she needs is a bit of cunning.

“Who are you?” he cries as she stabs out wildly.

She doesn’t tell him she is the circus master’s daughter.

She doesn’t tell him how loved she was in these parts once. The tiger’s wife.

Instead she whispers: “My name is Baba Yaga and I’ll eat you if you stay. I’ll chop up your flesh and grind up your bones. I’ll put a candle in your skull and hang it from my belt as a lantern.” The knife point scrapes his thigh bone and he staggers away in fright. So young. She almost smiles. Dragging his poor limbs like that, leaving a trail of gore. She’ll find him later if she must.

For now, soft needles beneath her and the world going dark. Noises in the forest, the silken swish of something out there moving. Two golden eyes, like two bad moons. The pale curve of teeth.

“Hush now, my love. I’m with you,” says the Tiger.

“It’s you then, is it?” asks Sara Sidorova. She feels as if her spirit has already left her body. “Old man, Grandfather Death. The devil in the wood.”

“It was you who loosed me.”

“I told you to take them and you did. Thank you.” Somewhere else, her breath whistles between her lips in little gasps but she is smiling now.

“The boy was right. This wound will kill you.”

But she isn’t afraid. “I stuck him. Follow his blood and you’ll find a meal big enough to sate your hunger.”

“Is that what you want?”

“I want an ending,” she says.

“Good. Come away with me then,” the beast whispers in her ear.

Sara Sidorova watches as a magnificent, curved claw drags itself through the air, which parts like the stripling’s flesh. Then there is a road—a second road, shimmering black, winding, impossible. That second road becomes a staircase, a great twined chain thrown down to the earth. Inside her the baby moves like a song. Or is it a white bird? Smoke?

Sara Sidorova doesn’t remember standing.

She doesn’t remember setting her feet upon the path, but there, it’s done.

She is walking, then rising upward. She sees the black arc of the heavens, stretched like a widow’s veil above her, the forest beneath now, then all of Strana. She imagines the trembling of small creatures.

“Welcome, princess,” says the Tiger.

3

Sara Sidorova climbs until her legs ache.

She climbs until her soles bleed and her lungs constrict like drying leather. The soldier’s boots aren’t made for such dainty feet as hers. For an hour she rests on the stairs. What is the world now? A tiny thing, dwarfed by chaos and the killing cold.

There are stars here, but she doesn’t recognize them. Too close, too many. Then comes the dawn like warm light spilled under a doorway—breathtaking. The blue hand of evening lifts away and an orange sheen burnishes the earth’s surface. It resolves itself into a form she can understand. A burning figure in the heavens. A man.

For one wild moment, she thinks she knows him. Feliks had a way of moving… Husband, she thinks. But no, it’s a foolish thought. Whatever she spies traveling through the gloom—a god, an angel, some immortal thing passing on through the black—it isn’t her husband. Feliks is gone now.

Perhaps there are impossible things in the world but when a man is dead, he stays dead.

* * *

Sara Sidorova climbs and the world falls away. The pain slips from her limbs. She comes to a gate with great spindles of ivory and bone and eleven chattering skulls. They whisper in a secret language she does not understand. She would stay to learn it but something pulls her onward, a silver thread anchored in her soul, winding tighter and tighter.

“Enter, my love.”

The Tiger’s voice fills her up.

Sara Sidorova has always had a rebel spirit, hating orders of any kind but the thread tugs her onward and—oh, mercy!—what an elegant place she has arrived at. She is accustomed to cramped hostels, the cuss of the wind against her traveling tent. But now a crenelated dome stretches above her. White marble, glossy and nacreous. It reminds her of a skullcap, the mollusk shells she’d rescue from the river.

Then she closes her eyes, opens them, and she is in a cave.

Limestone drips like melted wax, layering itself into fantastic shapes. The damp air steadies her, redolent with the rich smell of smoke. A blazing peat bonfire makes the walls dance with movement.

So. It’s all an illusion. She smiles.

The cave is empty, but for two women in animal-skin cloaks, crouched beside the flame. Despite the quivering glow, no light seems to touch their faces. Sara Sidorova knows they are queens, though she could not say how, exactly. Only that she remembers the stories her grandmother told her. Sweet Sara, little Sara, I know a place the birds go in the winter and our souls go after death.

There is a second gate set into the farthest wall of the cave but it’s nothing like that first one she passed through. This one is iron—and that means something, doesn’t it? Everything in this place means something. Isn’t that how stories work?

She tilts her head and blinks the palace back into existence.

Can she even call it a palace? It’s more like a mausoleum. A hundred passageways honeycomb outward. There are no tables here, no carpets, no soft furnishings of any kind, except for two iron chairs sat upon by two regal women with gossamer veils obscuring their features. Before them is the fire, but the fire is also…

Oh. Oh yes. There he is.

The Tiger is impossibly huge. His head is the size of a wagon and when she tries to follow the lash of his tail she finds no end to it, only the flame and the darkness, braided together, long enough to cinch itself around the world.

Fear freezes the breath in her lungs but she won’t let the beast scent it on her. She is still the circus master’s daughter. Even here she is the circus master’s daughter.

“I knew you once,” says Sara Sidorova. “You were flesh and blood and I held you in my arms, didn’t I? Such a small thing you were. Not anymore, it seems. You’ve come into your strength.”

“Devil, you called me. Have you no kinder words for an old friend?”

She lifts her chin. “Tell me: who are you? Who are you really?”

The Tiger huffs and the stink of ash is on his breath. “I am Amba. That great beast of legend who some say will devour the constellations when the storm blows in at last from Paradise.”

He is playing with her. She knows his moods, his affections, and his petty jealousies. She did raise him—or one like him, his shadow self. She remembers the scent of milk laced with brandy. How the cub used to suck it from the nib of the bottle she held.

“And these others?” she asks.

His tail twitches in amusement. “They are my sisters.”

“Of course,” murmurs the circus master’s daughter.

“Come now,” says the elder woman in a voice old and creaking. She moves slowly, raising a withered hand to her brow where sits a diadem with a single fist-sized fire opal at its center. “We can speak for ourselves. I know the circumstances are strange, but you are long awaited, Bright-Heart—and very much welcome. My name is Zorya Vechernyaya.”

Gently the old woman pulls aside the glittering widow’s veil, revealing a face weathered by the ages: crepe-like skin, hair the color of mercury, a pair of dark, burnished eyes.

“You know me then?” asks Sara Sidorova. Should she be surprised? Truly?

“We do,” the marquessa replies. “We are watchers. We know everyone our brother befriends.”

“Watchers?”

Zorya Vechernyaya lifts her hand. Beyond the iron gate, the light really is extraordinary. It summons the spirit of color into all it touches. The dense forests of the earth below, the sleeping fields, and the wide ocean beyond, the deepest blue the circus master’s daughter has ever seen. She would stare and stare, drown herself in that blue…

But then a story comes to Sara Sidorova, about two sisters bound to keep order and the beast who rests his head beneath their fingers. A story of destruction, the end of the world. A story of fire.

“I know all of this,” she says slowly. “It’s like a dream I once had, isn’t it?”

Suddenly she feels that moment—the moment that comes in every performance when the light shifts, the music swirls, and the story changes. The words are there, waiting for her to speak them.

“It is your duty to close the gate of heaven,” she says to Zorya Vechernyaya. Called the Evening Star in all the old stories. “And her,” she turns to the old woman’s sister, Zorya Utrennyaya, who has remained as still as a statue, “she will open it again, won’t she?”

“Perhaps,” says the Evening Star drily, “in a little while. When the time is right.”

Sara Sidorova contemplates the three of them. The two queens—the elder and the younger—and the fire-beast between. An iron chain is all that holds him back from devouring the world.

It’s such a little thing to do so much work, isn’t it?

Ah, but the Tiger, it seems, knows her thoughts. “To be chained thus is no great burden, my love.” His lips curve in mimicry of a smile.

“The one I knew was too proud. The one I knew hated any kind of confinement.”

“I’m not the one you knew, Sara Sidorova.”

“Of course you aren’t,” she says though she recognizes the scent of him: carnival musk and sweat and buttery sebum. “What is this place then? Where am I?”

“There are many names for it. Lookomorie, the Thrice-Tenth Kingdom. Sometimes it is called the Palace of Stories,” says the Evening Star. “Now come. I see you are cold and weary, half-starved, lovelorn. Please. Will you make yourself comfortable?”

Still her sister does not speak.

“I’m your guest?” asks Sara Sidorova. She knows there are rules for guests, special considerations. In a story, everything has a rule that binds it.

“You are my guest,” says the Tiger possessively. “None have rights upon you but me.” His tail lashes the air, a hook of flame in the darkness.

* * *

As it turns out, Sara Sidorova is cold and weary.

Her muscles ache but the practiced grace of her childhood returns to her as she settles herself against the warming flanks of the Tiger. There is no other place for her and he, at least, is not a stranger. Not fully.

Amba, the great beast of legend.

The sound he makes now is more like a barn cat given cream: contented. All at once he is no bigger than he should be, no bigger than her own tiger cub was when her father gave him over. She feels the bronze gaze of the elder sister upon her as she gathers him up in her arms and lays his gorgeous, striped head upon her lap. She expects it might burn to touch but it doesn’t.

They are still watching her. Waiting for something else.

What is it? What has she missed?

Sara Sidorova lets her eyes linger, soaking up their beauty.

She is used to being around beautiful women—Lil and Lis, the circus acrobats—but these ones… Their beauty is of an entirely different order, isn’t it? Their outer garments are of silk and fine brocade, indigo and violet, with sleeves folded back to reveal white lace cuffs, jeweled with garnets. Up her gaze travels to the dazzling headdresses formed of seed pearls and fountains of lace. Now she remembers sitting with her mother, listening to the radio for news from Hraná City, the progress of the war. Back then Sara Sidorova had lusted after such finery. A red corset with real whalebones, a comb adorned with ostrich feathers.

She touches the dead man’s gymnasterka, finds the buttons, then moves upward, searching for the bullet hole with her fingers. They come away sticky with her own blood. For a moment, she had forgotten she was dying.

“It seems I have no need for stories anymore. Watchers, you called yourself. Then you will have watched. You will know the world is nothing to me now.”

“We understand you have suffered,” says the Evening Star.

“Don’t demean me! Suffering I can bear. Thirst, hunger, pain, all of that speaks only to the body, but this is more. This is…”

“Desolation.”

“Yes,” Sara Sidorova answers slowly. “It’s only the living who suffer. And I’ve passed beyond that, haven’t I? If I’m here.”

There are cycles, aren’t there? Repetitions.

“The great beast of legend, the eater of worlds. I know you, don’t I?”

Her fingers land upon the soft fur of his ruff, gently exploring. Then she discovers the thing she was searching for. The collar that circles his neck is cold to her touch. Iron, like the gate. It’s always iron in such stories of binding. But who thrust the spike into the stone? Who could snare the Devourer? Her fingers creep further and she finds the catch. How simple it would be. Another little move and everything could be undone.

“So. This is why you brought me here,” she says to the Tiger. “To set you free upon the world. That’s the way, isn’t it so? In all the old stories the princess must choose…”

Now the beast’s muscles quiver with a killing spirit. That’s all the answer she needs. Even at the edge of the universe, it seems, there’s no escaping the past. Is it really a choice for one who has suffered as she has? For one who has lost what she has lost? She undid a collar very like this and there was blood after. She was glad of it.

“Take everything then. Take the world. Take the boy with his rifle, take his captain too, the soldiers, the trappers, the stalkers and huntsmen.”

Her thumb slides toward the catch.

“Wait, girl, don’t be so stupid!” cries the Evening Star. Her knuckles are bloodless and white as pearl.

“Ah, but she has chosen! It’s done now, and easily too.” The Devourer fixes Sara Sidorova with his yellow glare, urging her on. “Go on then, unchain me. You’re finished with the bone orchard. What could possibly remain for you down there?”

His eagerness is hot and heavy, a scent as strong as sex.

But then a thought comes to her. The burning man traveling through the darkness. And another memory fluttering: “Bitter, bitter, bitter!” the men shouted at her wedding dinner. They drank samogon afterward and she kissed Feliks, to chase the bitterness of the world away for all of them—

“The matter isn’t settled, brother,” says Zorya Vechernyaya more quietly now. “Not yet, not so easily.”

—and she knows this is a performance: the wonder and the strangeness, so shocking to her senses. It is all an attempt to astonish her.

“I’ve been forced,” she says. “Forced and forced, stripped of choice. But I won’t be your plaything in this, whatever it is. No more games now. Tell me everything.”

“Everything,” says the Evening Star with a note like irony. “That I cannot do. The world is too vast, my dear. But I can show you something.”

“Sister…” A warning note from the beast. Or perhaps something else—an echo of longing?

The moment is over too quickly for Sara to parse because now the light is blinding: first silver and then the color beyond silver, the color silver strives after. The sky is rent. Then Sara Sidorova is falling, falling through the night…

4

There is a light blinding the girl in the cage.

Perhaps you’d call her face common: a smooth forehead, pale skin, sharp cheekbones above flat cheeks. Long limbs, a slight dimpling at each elbow. She wears a corset of crimson silk. Girlish hips, a pretense of breasts. The girl is barely sixteen but already she is a beauty in the making.

Her name is Sara Irenda Lubchen.

“What do I care about this one?” demands Sara Sidorova. “You promised me an answer and I’m tired of games.”

“Be patient,” says the Evening Star. “There is a proper order to stories. Let me tell it my way.”

The cage is on a platform, lit by a spotlight, bordered by red velvet curtains. Beyond—in the darkness—is a sea of bodies, the girl’s audience. She senses them from the sounds they make, the rustling and nervous breaths.

Now she begins to move as if in a dream. She knows what she must do, what she has promised to do. Out there is the man she has promised to kill. She is frightened, poor girl, but she masters her fear quickly.

“I love you,” she whispers, to herself, to us. “I love you all.” And despite everything, despite the cage, despite the corset, and despite the package of death hidden inside, she does love them. But her love is a feral, violent thing. She tells herself what she has set out to do, she can still do in love…

“She hasn’t learned how to lie,” says Sara Sidorova.

“That will come in time.”

“Tell me, who is she? I think I know her…”

Carefully the girl steps toward the bars of the cage, her head cocked. It’s instinctive, an animal gesture. Her nostrils twitch. There’s a predator inside this cage with her, behind the secret panel. She knows he is there. She’s afraid of him, in her own way, but not as frightened as she should be.

“It’s him, isn’t it? Your brother. Why? What does he want with her? Stop pretending now!”

“Oh, but the self is changeable, Sara Sidorova. Your father taught you the rules of magic and that’s the very first, isn’t it? A thing is what it is only as long as belief holds it in place. And belief can make a thing larger than it is, like a light throwing out a long shadow.”

“Go on then. Show me what this girl can do.”

The lights go out. A hush falls over the crowd.

Sara Sidorova draws in a breath.

“Do you wish to linger?” asks the Evening Star gently. “Of course you do. You think you’re a renouncer, recanting life, cursing whatever your eyes fall upon—but I know differently.”

“Enough! Let the beast take her if he’s so hungry. What’s one more, then? That girl is nothing to me.”

“Has no one taught you patience? Never mind. I drank from the milk of the heavens and I have seen a thousand earthly kingdoms rise and fall. My years are infinite. I set the clock as I please. And I can turn it—like so…”

5

And so we have light.

The light of a new day, a new life.

Here is a babe—newborn and blinking. She has the same delicate skin, the same copper eyes. See that lovely brow? She knows no more of the miraculous than any other child. Yet all children are born miraculously. They emerge from a place of darkness and fall into—in the best cases—love.

“Would you tell me there’s love in the world then? Liar.”

“There was for you, Sara. Once you were in love and eager to greet the new day.”

“Once I was young and my head was full of nonsense.”

“What is this one’s filled with? A babe’s greedy anger and hurt. Someone must teach her to love, don’t you think? But here she is, arriving into a world of chaos. It’s good to watch from the beginning.”

“What’s that awful noise?” demands Sara Sidorova.

“Sirens. There’s been an explosion. Three blocks from the hospital…”

The child feels the vibrations and lets out a cry. Cold air, bright lights, sweet air. Her mother holds her to her breast. “You wanted to be born, little mouse,” she whispers, “and so here you are.”

Her papa asks, “What shall we call her?”

“Sara,” says her mother. It means ‘princess’.

“Irenda,” he replies, which means ‘peace’.

Thus, they name her according to tradition. For her mother’s mother.

“This is your granddaughter, Sara. Blood of your blood. If you choose to live.”

“If I live.” And Sara Sidorova’s hands move protectively to her belly as she looks at the child’s mother.

Else, her own daughter.

It is too much, too fast. She feels lightheaded.

“I think she sees us, don’t you?” says the other. “Hush now, sweet thing, you have your name. No matter the noise, no matter the dark, no harm will come to you this day, I swear.”

“And tomorrow? Don’t lie to her. Don’t let it begin with lies. Tell her what’s coming.”

“Tell her yourself, Sara,” says the Evening Star. “For now we’ll turn the clock again and leave the poor child to grow. When she is ready she will attend upon us.”

And so the light flashes and the world whirls away.

6

Look, Sara. The light really is quite wonderful…” says the old woman with a chuckle.

Zorya Utrennyaya, the Morning Star, her still silent younger sister, is moving. The glow of the rising sun limns the outline of her robes. Sara still cannot see that one’s face, but she breathes in the tangy air and tries to remember what she was thinking of. There should be a dawn song, shouldn’t there? Waxwings and bluethroats and… What else? What else?

But the thought has vanished. Her body feels like molten silver beginning to cool. No pain now. Beyond the gate the earth is washed in hues of lavender and coral, sunflower.

Crimson.

Heart’s blood.

There, now. Yes.

She remembers the seep of her blood through the jacket. How it felt for her heart to beat: the steady thudding, like the younger Estes’ drum summoning the circus performers to the ring. Thrum di dum, thrum di dum—but where is that rhythm now?

“I’m dead, aren’t I?” she asks. “That vision—it doesn’t mean anything. The boy shot me. I felt the bullet go in.”

“Dying, maybe. Yes. Almost certainly,” answers the Evening Star. “Oh, child, is that what you want? Of all the wishes in the world that one is easiest. If you ask me, I’ll unstop the hole in your shoulder and let your blood flow again. The birds will come for your body—”

Wings black as a seam of coal. Oh, she knows about the birds, doesn’t she?

“—Or the wolves, wild pigs. Anything with sharp teeth and a growing hunger.”

“That girl was my granddaughter. Irenda, they called her.” She tries to feel the kick of her daughter but there is nothing. “So it seems I live.”

“Maybe,” growls the Tiger from his position of repose, feigning disinterest. She has seen this tactic at work before in her own cub. “Maybe you live. Maybe you die. Pffft, does it really matter?”

“This is a place of stories, Sara,” says the Evening Star. Her copper eyes shine with reflected light. “Every story has a choice.”

“So maybe I live.”

“Yes.”

“Then show me the girl. My granddaughter. That’s what you want, isn’t it? Let her speak for herself.”

Now the old marquessa is smiling and Sara Sidorova knows she has stumbled into a trap. But how could she not? How could she know where the snare lies, the pits with their spears? All of this so far beyond what even she might understand of the world…

“Look again, Sara.”

Then the Evening Star reaches out and clasps her chin, directing her stare with fingers immeasurably cold. Their gazes meet with the force of an electric shock. That face, almost plain beneath the layers of finery, but impossible to ignore.

The same face as her granddaughter: common but somehow beautiful. Except this one is older, far older. And her smile is like Sara’s smile but… not. Less forced, yet it gives little away. The Evening Star tilts her head—Sara Sidorova has practiced the very same gesture a hundred times, a thousand—and it’s like staring into a looking glass.

Curiosity. Wonder.

“Oh, Sara,” says the Evening Star. “Grandmother. You were so different when I knew you in life. Omen of ill luck, I called you. Teller of tales, outcast, thief… Well, I never meant it cruelly!” Sara hears a young girl’s laugh in that age-scarred throat. “In the lands of the living we’re seldom our best selves.”

“That child you showed me—it was you. My granddaughter? How can it be?” demands Sara Sidorova.

Still the smile.

“So I am. So I will be. A story can change as well as the self, can’t it? It was you who taught me that. It grows as the teller grows, alters as the world alters it, sheds its skin like a snake—we are very like a snake, aren’t we? You and I? A snake the devours its own tail… oh yes. I think so—”

Sara Sidorova blinks. She expects the other to vanish, for the world to change again, but still the old woman stands before her.

“—stories are like that,” continues her granddaughter. “Sometimes they are a knife that cuts the master’s hand. Sometimes they live and in living breathe new life into others. Sometimes they kill and sometimes they die. Would you know my story then, Sara?” Coyness, at the last, and something else: hunger.

“Yes,” whispers Sara Sidorova.

“Good,” comes the reply. “Then listen, my sweet.”

7

“Shall we begin the old way then?” asks the Evening Star.

Once there was a girl. The girl was on a train headed to the capital, to Hraná City—best of all cities in the best of all possible worlds…

“I see green, nothing but green for miles,” says Sara Sidorova. “Where are we?”

“In the east now, crossing through the wildwood. But perhaps you’ve never been this way. You always kept to the coast, didn’t you? The harbors and the ports, the blue places. It’s different inland: all evergreens, oaks, and black gum, a thicket of savage weald our people still haven’t managed to tame. The land fights us. It always has and always will, so they say—but just wait a little and the shape will change. Soon the land will grow flat and tameable, chalky fields of monocrops, then rivers again and the summerhouses of the wealthy, then the industrial estates, the munitions factories…”

The girl in the carriage was an orphan. The girls in these stories always are, aren’t they?

She clutched a letter in her hand and her heart was filled with death. The letter said very little she could understand, nothing of grief and even less of love.

The girl, of course was me.

I was a good girl but my parents had died anyway. I was a smart girl, a pretty girl. All the papers said so. They remarked on how somber I had looked at the assembly for mourning, how very beautiful in my black scarf and silk dress, kneeling before old General Cvetko’s ikon.

In stories these things matter, don’t they? Being good and wise and pretty. Being an orphan, even. In stories these can position a girl in a certain way: for marriage, if one is lucky—or happiness after certain violent trials. It is the good girl who tames the witch. Lady Pale-Throat, the loyal daughter, willing to serve if she must to get what she wants. She might be possessed of special talents. She might speak the language of birds or have a cloak that can turn her feral, claws and teeth and a taste for man’s blood…

Well. What are those but stories?

“Tell me. How did she die? How will my daughter die?” says Sara Sidorova, her hands curling around her belly.

“A bomb blast in Assembly Square. Separatists, they said, and agitators. Seditionists, treasonists, collaborators, demagogues. It was widely reported at the time. So widely, some said, that a story emerged months later claiming certain news outlets had reported the explosion before it had technically occurred.”

“Did she… suffer?”

“I can’t answer that, I’m afraid. Not all travel the same road when their spirit slips away.”

Mama and her dying…

In those early days after the blast I used to try to imagine it. How she must have seen a brilliant shingle of light and all the world receding. I like to believe she felt nothing though in truth my mother had never been afraid of pain. Pain, she often told me, lives only in the body. The mind forgets pain, which is why mothers have second children.

And Mama desperately wanted another child. Not because she didn’t love me—no, she was a rare woman of love, my mother. She was much remarked upon in Stary, the little town where I grew up. It was not a place where there were many such as her: full of laughter, love for my father, love for me. Her house had wild dill in the yard and chamomile blossoms whose puffed-up lemony hearts she would dry in the cellar. She adored all the small, fragile things of the world and every kind of singing delighted her:

That love shining in your eyes.There’s the missing moon.No harm done I know…

Sometimes I wonder if she would have liked another daughter better than me. Even back then I was a difficult child, stubborn as a crab, my papa used to say, and secretive as all the children of Stary were.

Well, what else was to be expected? I had grown up in the shadow of a war I never understood. At school I was taught to love death. I wrote endless compositions about how I’d like to die in the name of… By the age of twelve I’d earned a reputation. My teachers took an interest and often I read my compositions at assemblies.

I was a good girl, you see? So very well-informed.

* * *

In Stary, for a time, my grief made me special.

I was the daughter of heroes. All the dead were heroes. I was told this daily by Miss Boban, my caretaker. She stayed in the house with me after. Her lessons included regular grieving exercises. Jumping jacks and journal writing. I wrote every morning in our parlor, rubbing my big toes together when I couldn’t think what to say next. Grief-addled, she called me. She insisted I give her the journal for safekeeping before I slept.

“How proud you must be,” she would tell me, brushing my hair, thinking the shock had left me feeble. Sometimes she’d whisper that she loved me and she wasn’t the only one to do so. Eyes followed me when I ventured outside, a chorus of whispers. It seemed I’d become a rare object of fascination. Certain apparatchiks took to remarking on the paleness of my cheeks. These weren’t lewd comments, you understand, not then—but comments of particular note, nonetheless.

Their attentions were observed, of course. Stary was a place of observation. Every glance was documented and disclosed to the proper authorities. Before long it was deemed an intervention might be necessary. Though we were many miles from Hraná City, it didn’t take long for word to arrive. It would be better, everyone agreed, if I should find a home elsewhere. For my own sake.

So. My journey.

On the train now I was no one. Unloved, dispossessed. Poor too despite the promise of a state subsidy when I arrived where they had told me to go. I slept seldom and when I did it was fitful and anxious. Often I woke in tears. Sometimes a woman—often a mother—would take my hand and try to comfort me but I was afraid of strangers and didn’t easily give myself over to their kindnesses.

In my hand I clutched a letter. The letter was handwritten on cheap paper and every so often I would press it against my knees to smooth the creases.

When you come to me, leave no trace ofmy daughter. No hair, no blood!Burn the clothes you cannot carry.Burn her books. Burn her bedsheets.Burn this letter.There is the body and there is the body.Bring only ashes.

This letter was from you.

I was a good girl and so I had tried to do as you demanded. Beside me was a suitcase filled with my mother’s refuse: old cotton dresses, her bedsheets, her most loved books. All of them had been shredded or torn—her samizdat, the few forbidden Rosettis and Ravenskayas she had hoarded—all cut to pieces by my own secret hand. I’d had no idea how to burn them without Miss Boban seeing.

“Let it be enough,” I’d said to myself as I ripped through the delicate pages, “let it be enough.”

I had loved my mother fiercely but now she was dead. I’d been forced from my home: wild dill and singing and yellow blossoms like little victory wreathes. I must forget the dead, they told me, it would be better that way, easier for me. Strana was a country that looked forward, only forward, ever forward. Here love grows tired, history vanishes, and nothing needs to linger past its day.

“I see something on the horizon,” says Sara Sidorova, “what is it? It seems like a fortress of light... a thousand winking eyes in the darkness… I never saw such structures in my life. Is this the capital then?”

“Oh, we are coming to it, Grandmother. To Hraná City, the best of all cities. To Baba Yaga in her palisade of bones.”

8

Morning arrived with a steamy blast from the engine that frightened the rooks from their perches. A cloud of dizzying blue-black wings met us as the train pulled into the station. Bad luck, if you were the sort to fear such things.

Not me, of course.

I’d left Stary but my grief had followed like a kind of glamour. That was clear right away from the face of the civil servant who had been called upon to usher me into my new life.

“I trust your journey was well?” he asked politely but his eyes lingered, searching, scrutinizing, attempting to suss out whatever it was that made me shine so.

Orphan, orphan, orphan I wanted to shriek, but the travel had cast a spell of silence on me. I nodded imperiously. He was a functionary—and that was enough for both of us. He took his place behind the wheel of a black armored sedan and slid shut the privacy partition. I suppose he was used to driving around a different class of passenger—the Deeps, perhaps. The Department for the People’s Protection. Even in Stary I’d heard stories about them. How they were human lie detectors, how they didn’t need to sleep.

In any case it didn’t matter. I had nothing to say and was happy for him to drive in silence.

The outskirts of Hraná City were sprawling and the sprawl was both ugly and bleakly impressive. A shivering afternoon light slid between ashlar facades twenty stories tall. From time to time a bridge would cross us and in its blue shadow handkerchiefed women hawked mushrooms the size of lamb hearts.

The engine bled gasoline and the driver took his time. There were no sights to point out. Victory Square lay further west as did the fabled Fountain of the Princes, the Winter Palace with its thousand rooms and courtyards, its sea-green copper spires, the Capitol Buildings, the seat of the senate, of General Cvetko himself—but those weren’t for me. I was the daughter of heroes but we were no longer in Stary. Already my mother’s time was passing, she was passing, out of the realm of living and into…

Somewhere else.

As we drove along the magistrale, I set about making my own plan to join her. A rope would be best to end my life. Braided from my bedsheets, perhaps, if nothing better could be found. Poison would be hard to come by and painful if maladministered. Drowning would be difficult and fire more terrible than poison. Falling would be acceptable though the building must be high enough to guarantee certainty. At least there were enough of those around.

Thinking this way made me calmer so I dozed as the car carried me into my new life. My almost certain death. The light was weak and yielding. The asphalt whispered its secret song as it sped into the distance.

* * *

Then:

“Who’s this one? Speak up, girl, at my age I don’t hear so well. What are you? A lump? A parcel? What’s your name? What are you doing on my doorstep?”

“Well now, Granddaughter. I suppose you’ll say that old crone is me,” demands Sara Sidorova.

“What can I tell you, Baba? The years are seldom kind.” A trace of a smile on her lips.

“But how old is that one down there? A hundred? A hundred and two? Her face looks like a pickled onion! I swear to you, my own mother was beautiful, even in old age she was beautiful! But her… her…”

“Oh, I confess my first impressions weren’t good either.”

You clutched the doorframe as if I’d woken you from a deep sleep. Rheumy eyes, a shapeless black frock and a briny aroma that followed you out into the hallway. One long severe braid hung like a noose from your scalp. But still you held yourself like a boyar-wife—mad perhaps, but your back was straight, your gaze fierce.

“The girl’s name is…” my driver started but you yanked up my hand and held it an inch from your face as if you might read my fortune quicker than he could tell it.

“Sara Irenda Lubchen. Yes, yes, of course, I’m not a soft skull. Consider her safely delivered. Tell whoever you need to she’s with family.” With that you hauled me inside and slammed the door.

The smell was worse here. It hung like a sweat in the air. Thick preserving jars balanced on unsteady shelves: eggs and walnuts, beets swimming in magenta vinegar, cucumbers, cabbage, and tiny sour green apples. But I didn’t have time to take it in.

“Did you do as I asked? Did you burn my daughter’s things?” You were stamping your feet on a shapeless saffron-colored rug. “Come now. Irenda—” you tasted my name in your mouth “—you must answer me quickly.”

I shook my head.

“Foolish girl.”

You snatched up my suitcase and set about unlocking it. Out came a strip of bed linen as long as my arm. A few scraps of poetry fluttered to the ground.

“This was my Else’s, wasn’t it? It tastes of her. Like lemons and apple blossom,” you said as the ribbon traveled from your fingers to your cracked coral lips. “You should have consigned these to the fire, girl. You should have let her find her rest. Did no one teach you anything of value in that stinking place she raised you?”

I kept my silence.

“Answer when I ask you a question. I won’t live with a mute.”

“In Stary, I had excellent scores,” I told you stiffly, “in geometry and history. I know how the seven princes died and the name of every man who fought at Cheyory Bridge.”

“Trivia, trivia, trivia, just as I expected,” you shot back with a scowl. “What a bad start you are off to, Granddaughter. But I’ll do what I can. I’ll have to, won’t I?”

* * *

Your apartment was five stories up, made of red brick balanced on rusted steel struts. Its spatial features were peculiar, the partitioned remnants of a communal style of living long since abandoned: narrow hallways and jigsaw rooms. The balcony held a glassed-in bathroom along with strings of dried red peppers.

“This is yours now,” you told me as you pushed me toward a cramped room behind the kitchen. Inside it was a mattress. The rest of the furniture was modular: a standing mirror that doubled as an ironing board, a stack of four boxes I was told could be anything I wanted: a stool, a sofa, a bed, a table for the old sewing machine that took up half the closet. Immediately I hated it.

“It’s make-believe,” you snapped. “Just make-believe the furniture.”

“Yes, Baba,” I whispered. Imagine dull lead softening. Impossible? Well, your face did. Not much, but I swore I saw it. You thought I knew nothing but Stary had made me a careful observer.

“Well, girl, do you want tea? Do you need to pass water?”

I shook my head.

“You must be hungry at least, with all the miles you’ve traveled. Eat when you have the chance or starve later.”

“No,” I intoned. A hunger strike would do as well as anything else. I wanted to deny my body.

But then my stomach rumbled gassily and you were pulling me into the kitchen before I could refuse you again, saying, “Good, good. Only shadows don’t eat.”

Well, so what if I was hungry? It had been three days on the train and I dearly missed my mother’s cooking. But in your kitchen were only more preserving jars stuffed with mummified cranberries, horseradish, and thick-skinned tomatoes. Did you live on these? It seemed intolerable. I’d have to kill myself soon and spare myself a horrid breakfast.

While you set about collecting specimens to fatten me up, I was left in an airless living room where a masonry heater piped warmth through a maze of black pipes. The bottom third of each of the walls had been painted moss-green, the work abandoned evidently. Above the divide, dusty cupboards hid an assortment of worn crockery and knick-knacks.

In Stary, snooping on one’s neighbors was a time-honored tradition. When I opened one drawer, I found a blown-glass bulb that launched a snow-swirl of confetti as I shook it. Next was a fading picture of a girl. She stood barefoot in the flooding gutter, her knees splayed, gripping a pair of dancing shoes while a soldier with a black umbrella stood some paces behind. Seventeen or eighteen, rail-thin with a wild elation in her eyes. She had my mother’s delicate, heart-shaped mouth. I pried the picture from its frame to search for some hint of when it had been taken. ‘Mirko, after the war’ was all I could find written there.

“I married that one,” you said from behind me.

Who knew you could move like a panther when you wanted? I spun around to find you holding a board with buttered rye bread toward me. “Your deda was kind in his own way. You won’t remember him, I expect. You grew up too far away. Put the picture back, child. The light will spoil it.”

It was you then. Not my mother at all.

“But that can’t be right,” says Sara Sidorova. “My husband was Feliks.”

“It hasn’t come yet, Sara. The girl in the picture is still ahead of you.”

“Why did you send me that letter?” I demanded. In truth, I suppose what I really meant was, what’s to become of me now? I had no one in the world but you and by that point it was becoming clear to me you were a grotesque, a witch woman, a fossil gone grotty in the head. I had seen war widows like you in Stary. The state madhouse was full of them.

“You look like my daughter,” you murmured as you sank into the wing-backed chair near the stove, balancing the board on your knee. “Else was so skinny when she was your age, like a little boy.”

Oh, but just hearing Mama’s name was a release. “Will you tell me about her? Will I sleep in her room?” I would have knelt at your feet had there been room enough.

“You want stories, go find a storyteller.”

“Please!”

You pressed your lips together and said nothing.

“Tell me about her childhood, Baba. How was she born? What kind of girl was she?” I could see the questions were an affront but I couldn’t stop asking them.

Suddenly rage pooled in my stomach, the back of my throat. Then I was thrusting the old photograph toward the stove.

“Tell me,” I hissed, “or I’ll burn this picture! I swear I will!”

Who were you supposed to be to me anyway? My grandmother? Mama had never spoken of you, neither her nor my father. All I had was your name and even that they’d never bothered to use. You had been happily abandoned and now you inched round the room like a whelk and I wanted badly to hurt you further.

Ah, but I was wrong about you—and not for the last time.

In a flash you were out of the chair. The bread flew, the board clattered, and the metal grate hissed like a cat as you flipped it open to show me the glowing orange flame. I swear your fingers must have been blistering from the heat but you didn’t even flinch.

“Oh, child, you think I’m so easily cowed? There’s a beast at the heart of the universe,” you spat, “and he’ll gorge himself on your wanting, if you let him. Some call him the fire in the night, the great devourer but not me, oh, not ever me. I tamed him, Granddaughter…”

The heat jellied the air and I took a step back. You smiled then, and that crooked smile of yours was worse than the heat because I could see you weren’t lying.

My hand dropped slackly to my side and the picture floated to the floor.

But then your face changed, your smile twisted and a terrible coughing racked your body. On and on it went, bending you over like a question mark. When the fit passed, whatever it was I had seen in your eyes was gone. You slumped into your chair, boneless, just another old woman, just another husk who had held on long past her purpose.

This was why they had told me to forget. Some things lived too long. I swore I wouldn’t make that same mistake.

Carefully you plucked the picture from the floor. “Your mother thought the world was a place for singing. Now she’s dead. Let me mourn her. Tomorrow, we’ll talk, Granddaughter. Tomorrow we’ll set things right…” Then your eyelids drooped, slid shut and your body went slack as a windless sail.

You were asleep.

Was I sure?

You could have been pretending… but no. It was as if your age had crept up on you. Your skin was translucent as onion paper, the veins a crosshatch of velvety blues and purples. Maybe you thought you’d tamed the beast but it was clear as still water that Death had sunk his teeth into you.

But the anger was inside me, a red flush creeping up my neck. I took the iron poker and imagined bludgeoning you to death. I dreamed of driving you into the oven myself as all the brave girls did when they met a witch in the forest.

A beast at the heart of the universe, was there? Let him feed, I thought, let him take it all. What need had a girl like me to resist him? There was nothing for me here. No love, no kindness, only the great millstone of pain I’d carried around since the day my mother had left me.

* * *

So.

I tied the bedsheet carefully under my chin, then tested the running knot.