2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

1920's Mexico and the American Southwest hold many dangers, as the last Apache strongholds persist against the foreign invaders.

Hard as nails, Confederate serviceman Jock MacNeil receives an unexpected invitation to guide runaways from a reservation to a stronghold in Sierra Madre.

Facing both Mexican and American authorities, and the Apache Wars raging around them, Jock witnesses first-hand the terrors of war, and his own transformation from a man of faith to Apache spirituality.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

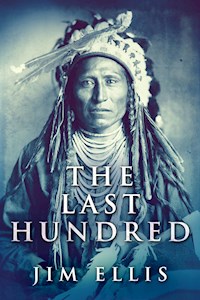

The Last Hundred

Jim Ellis

Copyright (C) 2011 Jim Ellis

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2019 by Next Chapter

Published 2019 by Next Chapter

Cover art by CoverMint

Edited by D.S. Williams

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

Acknowledgements

Dave King for editing The Last Hundred, contact [email protected].

Thanks to Cynthia Wiener, Libby Jacobs, and Miriam Santana for their support and encouragement; and a special thanks to my Good Lady, Jeannette.

“Jock never surrendered; not in 1865 or 1886, Cap'n. It's 1927 and he's fighting with his Chiricahua down in the Sierra Madre. A real Bronco Warrior.” —Joe MacIntosh, Scout.

Chapter One

The Apache call the Sierra Madre the Blue Mountains.

The range of nine thousand-foot peaks runs for a hundred miles from the Sierra el Tigre south to the Basvispe Valley. Three rivers bisect it: the Rio Aros, the Rio Bavispe, and the Rio Yaqi. The Rio Bavispe guards the isolation of the Sierra Madre. The continental divide flanks the range on three sides. The mountains mark the border between Chihuahua and Sonora.

Hidden deep in the mountains are small fertile plateaus. It is hot in summer, but the temperature can fall to freezing when the sun slips behind the ridges. It isn't a landscape for timid men – it's a vast, menacing land dominated by mountains and sharp rocks, precipitous cliffs, snakes, jaguars, and wild cats. It is a place for retiring armadillos and badgers; the benign white-tailed deer, brightly plumaged parrots. It was a killing ground where Apaches fought Mexicans and Americans with no quarter asked or given.

And it was home to the last free, independent Apache, who dovetailed with this wild place, snugger than a mortice lock.

Jock MacNeil, formerly of the Confederate Navy and Stand Watie's Mounted Rifles, stood at the cliff edge of the rancheria, raised his arms to the sun and sang the Morning Song. He was giving thanks to Ussen, the God of the Apache, for the heavenly gift of the love he'd known with his wife, Miriam, and for the lives of their son and daughter.

Jock wasn't a man who received divine grace on his knees. Ussen had given the land to the Apaches, even though the White Eyes took it from them, and their Government broke its promises. Ussen had also given Jock back his spirituality, replacing the primitive Catholicism which had slipped away when he was in his early teens, now nearly six decades past. Jock's voice, strong in the low registers, wavered on the higher notes, but strengthened as he offered his gratitude to Ussen for his protection from enemies and the bounties of the rancheria.

Suddenly, the heat of the sun vanished. A crushing sensation pierced Jock's heart, and he grew cold. Perhaps this was his time to die, and he hoped it wouldn't be painful. Slowly, his thighs gave way, his arthritic knees collapsed under him, raised arms dropped to his sides, and he fell to the ground. He lay, twitching and shaking, his legs jerking so violently that he thought they might separate from his body. A foam of saliva gathered at the corners of his gaping mouth and hung on his cracked lips.

But Ussen hadn't called Jock to the Happy Place, not yet. Ussen was sending the power. Jock could feel it. He was being asked to give another service for his people.

Suddenly, his soul left his body. He could feel a distant attachment to the shell lying on the ground, but he was transported to the old northern homeland. Homesickness and nostalgia swept through him as he saw his younger self with his wife and family, in beautiful Oak Creek Canyon. Oh, that sweet, happy time, that lost paradise.

Then the chin-a-see-lee touched his soul, and he was in the Parjarita Wilderness, the place of deep sorrow, reaching with crooked fingers to touch the earth where the bones of his beloved, Miriam, and their son and daughter lay in the grave he'd dug.

He sensed danger nearby and looked up. An aged man sat beside him. Jock suspected he knew him, though the old man's face was blurred. Farther back, a group of Apaches waited. The young men and women looked at him expectantly, and the old people stared pleadingly, and he did not understand why this was so.

Then he was once again in his body.

Jock gradually recovered. Presently he got to his feet, wiped the saliva from his chin with the sleeve of his calico shirt. Kusuma the old woman, who looked after him – and who was younger than he –stood by the side of his wickiup and beckoned him to breakfast. Jock wasn't ready to eat and subdued his desire for coffee, pretending not to hear her calling. He adjusted the ties on his long moccasins, doubled over and fastened them at the knee. He admired Kusuma's deft work on the curled-up toes, which protected his feet from thorns and cactus spikes. Jock felt around the leggings, smiled as his hand rested on the pair of Derringers hidden there. The Derringers were old and well-preserved, each one primed with two .44 rounds; fatal at close range. If he were cornered and disarmed, he might fight his way out, or shoot himself if it came to that. Jock adjusted his long breech clout, unfastened and fastened the buckle of a leather Mexican Cavalry belt, and played with the position of the sheathed Bowie knife hanging at his left side.

“Jock,” Kusuma yelled. “The coffee'll be cold.”

He tried to walk confidently to his wickiup, ignoring the torment in his knees; but Kusuma was not fooled and spotted his ill-disguised limping.

Jock sat in the arbor of his wickiup, facing the sun and thinking. He liked to sit here when he had a decision to make. The vision from Ussen had added to his power, and he felt stronger, confident that he could do whatever Ussen desired of him.

Kusuma poured more coffee. Jock took generous swallows, washing down the last of the stewed hoosh made from the fruit of the prickly pear. He liked to watch the women gathering the fruit – using two sticks to save their hands from the spikes – then rolling the fruit on the ground to remove the barbs.

“You're going north again?” Kusuma said.

“Yes.”

“What if you're killed? Take Jim, or one of the warriors.”

“Jim's in worse shape than me. He knows what to do when I'm away. I don't need a warrior to protect me; my power to go north comes from Ussen.”

“I'll prepare food and water for your journey.”

“Pack some hoosh.”

Hoosh kept him regular. Piles did not go well with long days in the saddle and were he to get wounded up north, Jock didn't want enemies laughing at his stained breech clout. Or if he were killed, he didn't want his soul to know the White Eyes' contempt for an old, fiery-bottomed Apache.

Although he was troubled by what lay ahead of him, Ussen's mercy worked on Jock. He looked around, and a smile of satisfaction creased his habitually stern expression at what the band had achieved.

It was good to be up in the high places, deep in the old Apache heartland where Juh and the Nednhi Apaches roamed in the old days. The dome shaped wickiup behind him was built well, the best willow poles supporting the brush cladding and the roof of shingle-style bunches of bear grass, fastened with yucca strings. A wavering ribbon of faint blue slipped out through the smoke hole in the roof, drifting northwards in the southern breeze. Inside lay his weapons, the few belongings, and the comfortable grass and brush bed covered with a deerskin robe where he eased his old bones when the arthritis was acute. It was a sturdy permanent home, warm and dry in the winter and cool in the summer, not like the temporary, rickety shelters used in the eighteen-eighties when the Apache were on the run, pursued by American and Mexican soldiers.

In the small fields below him, corn and mesquite beans grew. There was lush grass for the horses, sheep and cattle. Water was plentiful, and a small stream was dammed, creating a pool for the animals to drink. Game was abundant. In autumn, berries were to be had for drying. Agave grew in the valleys and the women gathered it to make tiswin, a weak beer. The women and children risked the fury of wild bees to harvest honey. Lower down, aspen and scrub oak flourished; higher up, firs and oak grew thickly. Through that high forest was a secret path up and over the ridge which Jock had cut; an escape route if the stronghold were attacked. Food, weapons and ammunition were cached up there beyond the ridge. Stones were carefully positioned along the approaches to the stronghold, and a boy, a girl, an old man, or woman, could send an avalanche down on enemies. For now, his people were safe.

But now the power was on him. Today was the day to go north and overcome the sense of danger lurking in his soul. Unexpectedly, regret tugged at his heart, and his throat swelled. Perhaps Ussen was sending him up there to his death. Perhaps he might not see his beloved rancheria or his band again, but he kept his anguish hidden beneath an iron mask.

Cherokee Jim was crossing the open ground separating their wickiups. Jock waved him toward a folded blanket, and Jim sat down, resting his arms on his knees. He handed Jock a long, thin, dark Mexican cigar and simultaneously, they bit off one end. Jock held a hot ember to Jim who drew on his cigar until he was satisfied it was burning well. Jock lit his own cigar, and they smoked contentedly.

“You're all right, going north?” Jim asked.

“I'm fine. I want to visit the grave of my family. Oak Creek Canyon too. We were happy then.”

Jock let himself drift back more than sixty years to Miriam, his beloved wife, a petite slip of a girl who was fifteen when he first met her. She'd had an ebony complexion and walked so proudly, and she was so beautiful. As her face came back to him, he thought his heart might break. Tenderness surged in his heart as he recalled reviving her from near death by drowning, remembered his anxiety as he set the broken bone in her right arm; the relief in her lovely face when he made her drink laudanum to relieve the pain of her wound.

Kusuma, who looked after him, was good company; a gift from Ussen and he held her in great affection. But he was often lonely, and though he had Jim's friendship and the companionship of Kusuma, sometimes he craved the affection that came only from women. As leader, Jock might have insisted upon the company of younger women, but he knew he was ugly to the young, and he kept his honor by respecting all the women of the band. It was a respect which grew from his love for Miriam and their children.

The two men sat quietly.

Young voices came to them from the edge of the village and they turned to stare. A few older children in two lines, twenty yards apart, hurled rocks from slings at each other, dodging and weaving the flying missiles. One girl finished nursing a bloody forehead where a rock had struck, then slung a stone at her adversary. Jock nodded and saw Jim nodding, too. Simple games like these were preparations for the warrior's path. The noise and youthful energy reminded Jock of his own son and daughter, but they'd been murdered before they could learn to fight.

Jock chewed on his lip as he remembered finding their dead bodies, the top of their heads a bloody mess, where the scalp hunters had cut and wrenched away the hair. He looked up at Jim. “Might go to my secret stronghold in the Dragoons, look at some of our old places. The last time, maybe. Ussen has strengthened my power. I must overcome something dangerous. I saw some of our people, young and old, and I think I'm to help them, but I'm not sure. Ussen will show me when he is ready; He will protect me.”

“I'll come with you.”

“I need you here.”

“You know,” Jim said. “Once, your hair was copper, as mine was black. The hair on your face is no longer red, now it is white. But you are too young to die up there, maybe?”

“I'm seventy-seven years old, Jim, and you're well past eighty. Time we both thought about dying.” His knees ached from sitting still, but he was too proud to stand first. “Take care of things, Jim?”

“I'll do that, Jock. And I'm coming down the mountain with you.”

Jim reached for Jock's fifty caliber Sharps Rifle and, squinting out of his best eye, took the weapon apart, methodically cleaning and oiling it. Jock checked and cleaned a pair of Confederate Cavalry pistols, and the Derringers. He took a .45 Colt automatic pistol and shoulder holster, with extra ammunition for security.

Jock didn't want trouble and wouldn't look for it. But he wouldn't run from a fight either. He'd face enemies if they came at him.

Satisfied that his guns were prepared, Jock looked around again. It was a fine rancheria, and he was glad his Chiricahua had added farming to their raiding skills. Jock liked the Sierra Madre, especially the Sonoran side of the mountain, more fertile than the Chihuahua slopes. His band had been happy and safe since before 1920, raiding in Sonora and Chihuahua, fighting Turahumari who scouted for the Mexicans, trading with a couple of villages to which Jock gave protection from bandits. And there was the small mine where they extracted enough gold to pay for new weapons and supplies. Jock had strived to live well by serving his people, but he worried about the small numbers of warriors and young women and the survival of the band. And it grieved him, that given the resources of the rancheria, they couldn't grow by much.

Perhaps that was why Ussen wished him to go out again.

Deep in his heart, Jock was haunted by the knowledge that these were the twilight years of the free Chiricahua; they were a shadow of their former selves, their power broken by the wars with the Americans. The Apaches had been battered to defeat by the forces of Manifest Destiny as a horde of White Eyes surged west, bringing civilization, establishing ranches and putting up fences, building railways, erecting telegraph poles, and stringing wire, digging mines and settling the land. Jock kept a special loathing for those Apaches who scouted for the military. He knew that the Apaches could have survived for many more years had they remained united. From time to time, he dreamt that they would never have been defeated by the White Eyes.

For a moment, long discarded Catholic beliefs haunted him, and he worried that Ussen's power was less than the sound and fury of the Holy Trinity worshipped by the White Eyes. But without Ussen's guidance, the band would not have survived. Jock had learnt that the God of The People eschewed the pomp, the thunder and lightning of God the Father, Son and Holy Ghost; Ussen's power worked through mystery and nuance, guiding Jock, allowing no man to sully the honor of the People.

One time on San Carlos when the People were bottled up on the reservation, an agent by the name of Reyes refused rations to Sigesh, insulting and striking her. She was the wife of Capitano Leon, a great leader Jock had followed. Jock confronted the man.

“Fuckin' renegade,” Reyes said. “You and your nigger squaw. I'll have you arrested.”

Jock pistol-whipped Reyes, the barrel of the Confederate Cavalry pistol fracturing a cheek bone and breaking his nose. Then Jock blew Reyes' brains out.

No, if the People were to retain their dignity, they needed to be free.

But how was that possible in 1927? In the last few years Mexicans had begun settling in the Sierra Madre, threatening the rancheria. It was only a matter of time before Mexicans and bounty hunters found a way to attack, and the band might be reduced by the fighting or threatened with destruction. Jock would devote all his power to avoiding that calamity and trusted Ussen to help the band survive and move ever deeper into the Sierra Madre. But a sense of an ending of things hung over him and dampened any optimism.

But he would wait and listen for the coming again of Ussen's power which had allowed the band to flourish in desperate times. He would show Jock a way forward.

“You're going to wear that old jacket?” Jim said. “I thought you'd thrown it out.”

Jock brushed the sleeve of the patched and darned waist-length jacket of steel gray wool. He fingered the rolling collar. The braid had worn thin and few buttons remained, not enough to fasten the jacket; and the cuff buttons had long gone.

“It's an officer's jacket. Captain Semmes himself gave it to me when I signed off the Alabama.”

“I know.”

“If I meet any Americans, I want them to know what I am and where I'm from.”

Jim finally rose and Jock followed. Kusuma led out his stallion, packed and ready for the journey. Jock stood by it, confident and proud of his appearance, satisfied he was dressed suitably for this journey. An Apache would feel Jock's spiritual strength, perceiving that he was enthlay-sit-daou – one who endures and remains calm, clear headed, and courageous whatever danger he faces. Mexican peasants and vaqueros would see that he was well-armed and dangerous and stay out of his way. But to the White Eyes, dressed as he was in high moccasins, long white breech clout, blue calico shirt and red bandana, with the antique weapons, and the Confederate Navy jacket, he was just a shabby old fool from another age; a renegade who'd gone over to the Apaches.

“Tell everyone I'm going north,” Jock said to Katsuma.

Jock mounted his horse, and the agonies of arthritis fell away. Confidently working the reins, bringing pressure with his knees, thighs, and heels; offering a soothing whisper in the stallion's ear. Jock and this horse knew each other well.

Jim mounted a black gelding and followed Jock through the two lines of his followers. Jock absorbed the silent respect of the old people, but the warriors and the young fighting women raised Mulberry bows and rifles overhead, pumping them up and down; their cries of 'Yiii, Yiii' making Jock proud.

Jock felt young again and reined the horse round to face his followers. With rifles held overhead they steered the horses back in dignified dressage to the start of the trail down the mountain, Jock filling the air with the cry of She Wolf, and Jim singing out the Old Rebel Yell that in the days with General Stand Watie had scared many a Yankee shitless.

They camped at a quiet place before the aspen and scrub oak faded, close to the start of the Sonoran desert, sitting in darkness and sharing a meal of beef jerky and water. Neither of them wanted to risk a fire so far down the mountains.

“Traveled far, Jock.”

“You too, Jim.”

“I remember the stories about the ocean back in the old days,” Jim said. “I saw the water at Galveston, and one time we went down to the Sea of Cortez, but I never saw the ocean. You've crossed it. You've come further.”

“You're right Jim. Scotland is a faraway place.”

Jock's White Eyes name was John MacNeil. He was born in 1850 in Westburn, a tough seaport on the River Clyde on the west coast of Scotland. Jock's family were Highlanders from the island of Barra. When he was thirteen, his mother died, and in despair his father killed himself, leaving Jock an orphaned apprentice blacksmith and farrier.

Wrapped in his blanket, Jock remembered going to sea soon after his father's death, signing on as Galley Boy aboard the Jane Brown, a schooner trading in home waters. His job was to assist the cook, a slovenly man. Jock smiled. Before long, his skills surpassed the cook's, much to the delight of the small crew. Because he had experience looking after sick and injured horses, and because the steward was usually too drunk to deal with them, Jock began to treat crewmen who were knocked about and felt poorly.

Jock let a hand warm his thigh, gently rubbing heat into an old injury, a legacy of his seafaring when he fell into the hold of the Jane Brown and convalesced for a month ashore in the care of Doctor James Gunn, a retired Royal Navy surgeon. Gunn had taught him to clean and dress wounds and bruises and to use the cautery and the suture needle.

James Gunn had washed the wound in Jock's leg with alcohol. It stung.

“Keep still, Jock,” James Gunn said. “An Irish surgeon told me about this when I was in the Royal Navy. I don't know why, but the spirit reduces infection. Use it on your patients.”

He never forgot James Gunn's advice.

Jock marveled at the direction his life had taken; when he was fourteen, sailing back and forth across the Irish Sea, he couldn't have imagined the path he'd choose, or the life he'd lead.

Jim rubbed his stomach and pulled the blanket closer. “Wish we'd a fire. Could've had rabbit and biscuits and coffee. This damned cold's hurting my arm.” Jim pushed back the sleeve of his calico shirt, rubbing his left wrist which had been broken in a Civil War battle. “You fixed this old arm good, but it still reminds me.”

Ach, Jim wanted to pick over old times, keeping them awake half the night. Jock's shoulders slumped, weighted by fatigue. Tomorrow, he faced a long day on horseback crossing the Sonoran Desert. He was in no mood for conversation but forced a vigorous nod.

“Then you found 'The Cause',” Jim said.

Jock needed to stretch out; his backside hurt from several hours in the saddle, and his knees sent out warning stabs of pain. Jock was so tired he risked an attack of piles and suppressed an urge to evacuate, leaving the motion dormant until early morning.

The hell with it. He stretched out, tucked the blanket around him. “I was rated Loblolly Boy, helping the Assistant Surgeon on the Alabama.”

“We met outside Galveston, and you bought the Hawken Rifle before we headed north to join Stand Watie. 'Ol' Rebel Soljers', eh?”

Jim kept talking, but his voice was growing more distant, odd words dropping out of the chatter, marring the sense of what he was saying.

And then Jock drifted into sleep.

Chapter Two

Both men said the morning prayer to Ussen, facing the sunrise, arms raised. The sunlight dispelled the chill and Jock was glad of the warmth as they ate their cold breakfast of beef jerky and water. Jock wanted a firm grip of his surroundings before he'd risk a small smokeless fire to brew coffee and prepare hot food.

“I brought this.” Jim held up the wooden-handled cartridge loader, a device resembling oversized pliers with crooked handles. “Make ammunition for the Sharps.”

“I'll find a place for it.” Jock packed the cartridge loader and the accompanying capper and bullet setter in the saddle bags. “Thanks. Extra bullets for the Buffalo gun never go wrong.”

They embraced in farewell.

“You'll be back in the stronghold tonight,” Jock said.

“Yes. Take care out there; watch out for the White Eyes.”

Jock watched as horse and rider diminished and prayed to Ussen that Jim would have a quiet ascent of the mountain. It would have been good to have Jim with him on the journey, because Jim was an unnerving adversary and knew how to deal with enemies. But Jock knew he had to watch his last friend from the old days slipping into the thickets of aspen and oak. He knew the risks of the way the last free Apaches lived: at any moment they could be killed by enemies. The band needed Jim with them more than Jock did. It grieved him that his friend of more than sixty years might die and he'd never see him again. But Ussen had willed it.

Jock hoped that it was Ussen's will that they'd meet again.

It was the morning of the second day and Jock rode across a prairie of short yellow grass. He relaxed in the warm air and dismounted to gather dried yucca wood. He favored yucca, so easy to start a fire with and burning smokeless. He'd chance a fire and have hot food that night.

Jock remounted and wheeled the chestnut, riding a short way to admire a flowering creosote bush –from a short distance, because he disliked the smell. Ahead, he could just discern the shapes of meadow foxtail and remembered the days, forty and more years ago, when the People rode freely across this land. Riding on he passed agave plants used to make the distilled spirit, clandestino or lechuguillaby, an opaque, heavy flavored spirit. In his younger days he'd tasted it; but these days he drank little or not at all, and never in the company of Mexicans, who'd been known to get Apaches drunk and then massacre them.

Jock felt good that morning as he rode north-east towards the Rio Bravo and Texas. The desert was beautiful, and he was at one with the land; his arthritis had eased, his bowel motions were soft and regular, and he'd stopped worrying about an attack of piles.

The tranquility of the early morning was shattered by the report of a heavy caliber rifle and the whip-crack of a bullet shooting past his head. He wheeled the chestnut around and was faced by an open motor car leading a posse of horsemen across the plain towards him. Mexicans most likely; hunters after game but prepared to scalp an Apache and collect the bounty money.

He'd let his guard down, swept away by the beauty of the desert. He was far too old for that kind of mistake.

Jock leant low in the saddle, and with knees and heels urged his horse around and into a gallop towards a dip in the ground, four hundred yards to his front. Jock had first mastered the dread of combat serving the Confederate cause, and his fighting skills were honed to perfection by his life as a Chiricahua. So he set aside his anger for allowing himself to be surprised by adversaries and drew from deep within himself a calmness as still as the eye of the storm. He drew the pair of Confederate Cavalry pistols from the saddle holsters as he rode, turned in the saddle and fired a couple of shots at the Mexicans. Jock was at long-range, but the shots might distract them.

The arthritis in Jock's knees stabbed painfully as he dismounted, guiding the stallion to the prone position just below the rim of the hollow ground, a maneuver learnt while riding with Stand Watie. Calmly, Jock rested the Sharps rifle across the saddle and laid a few rounds from his bandolier beside it. He got out the long glasses –his eyes weren't so sharp now that he was closing in on eighty years.

The pistol shots had killed the man now lying on the ground. One down and seven to go.

The Mexicans and Americans –surprisingly, he saw three of them dressed in khaki and stiff-brimmed campaign hats –stopped, and stupidly crowded around the car, not even taking cover. From the exaggerated movements and loud voices carried to him by the breeze, it seemed some members of the party were drunk. Perhaps the drink had given them the confidence to attack an old, lone Apache.

Jock wanted no trouble, and hoped they'd withdraw, and he'd get on his way across the Rio Bravo. But if not, he was ready. He was weary of being despised as an Apache, abhorred and feared for becoming a Chiricahua: loathed; a renegade in the eyes of Mexicans and White Eyes. Jock was ready to kill them all for their bias and stupidity.

From the car came a burst of fire from a Browning Automatic Rifle, aimed from the shoulder of a man in a campaign hat who stood in the rear of the car. The rounds flew harmlessly over Jock's head, but the gunner might find his range eventually, so Jock got him in the scope sight of the Sharps, and matter of factly killed him with one round to the chest.

Jock ejected the spent cartridge and reloaded the Sharps, then reloaded the Colt pistols and again examined his pursuers through the long glasses. They appeared to be rattled and frightened. Jock waited, keeping the Sharps trained on them.

The head of a pinto pony came up over the edge of the plain; then a man's head with black hair, bound with a familiar red bandana, streaming behind. A Chiricahua. The unexpected appearance of this lone horseman made him euphoric and although he could deal with his tormentors, he was certain with this newcomer's assistance he could destroy his adversaries. Ussen had surely sent this rider, and together they would triumph.

The pony came into full view, and no sound came from its hooves which were shod in short buckskin boots as they sent up spurts of dust. He got to within one hundred yards of the Mexicans and the Americans before they sensed the rider's presence. The Chiricahua worked the bow beautifully, and four arrows were in flight before the first one hit. Two Mexicans went down, one with an arrow through the neck, the other pierced in the torso.

Jock put two rounds from the Sharps into the radiator, immobilizing their car.

Jock executed an old cavalry maneuver; bringing the stallion's head up by the reins, getting into the saddle as his mount rose and he holstered the Sharps. Drawing the Colt pistols, he galloped towards the enemy while they were confused by the attack from both front and rear. His new ally killed one with his Winchester rifle and Jock got another with the Colt pistols. The one remaining Mexican and two Americans scattered. Jock met his new ally at the car and dismounted – gasping at the arthritic pain in his knees – and unholstered the Sharps.

“Hold the horse's head,” Jock said.

The riders moved fast, but Jock got a Mexican in the scope sight and was satisfied when his sombrero lifted as a round smashed into the back of his skull, and he flew out of the saddle.

He looked up to find the Chiricahua gathering the horses near the motor car.

“You shoot well,” the Chiricahua said.

“Two of your arrows missed. Let's get those two Americans.”

In a few minutes, they were in rifle range and brought the horses to an abrupt halt. Jock nodded to the Chiricahua, and they dismounted. This time he held the horses steady. The Chiricahua rested the Winchester across the saddle; with two rapid rounds the American riders were down. As they rode over to make sure they were dead, the horses drifted back to where the bodies lay. They were two officers, a Major and a Lieutenant in Army uniform; Arizona or New Mexico, maybe Texas National Guard, riding with these hunters.

So somebody must know the hunting party was out, but it was unlikely there would be a search party looking for them for several days. Had these two got back to where they'd started, there would have been a posse chasing them before nightfall.

“Kill the horses,” Jock said. “They might find their way home.”

The Chiricahua cut the horses' throats and they collapsed in fountains of blood. Jock regretted leaving good saddles, but it wouldn't do to over-burden themselves with loot. But they took the ammunition and the guns and returned to the massacre at the car.

“I didn't want trouble, but I guess we're a war party now.”

A thin smile creased Jock's face at the memory of an old Indian killer's words back in the eighteen eighties, “Apache war parties come in all sizes, from two to two hundred.”

Jock dismissed his first thought of burning the car and the supplies they couldn't carry; smoke spiraling into a clear sky would draw attention. They took flour, coffee, sugar, and meat from the supplies.

He told the Chiricahua to keep a piebald mare to carry the loot and had him hold the horse's head and whisper and soothe the animal. When the animal calmed, Jock removed the horseshoe nails and discarded the iron horseshoes which would leave clear tracks, then smoothed the hooves with a file.

“Put these on him.” He handed the Chiricahua a spare set of buckskin boots. “Can you jerk beef?”

“Yes.”

Quickly they cut beef into thin strips and hung it to dry from the saddle of the pack horse. Then they cut the throats of the remaining horses; releasing more gushers of blood. Jock hated doing it, but he couldn't let them drift back to where they'd come from.