3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1950's Westburn, Scotland, Tim Ronsard only has a few months remaining until he leaves St. Mary's School.

Bored and listless, he's anxious to get away. His life changes when a new music teacher is appointed: Isobel Clieshman, a Protestant working in a Catholic school. Soon, Tim's feelings go well beyond a school boy crush, but at 23 years old the teacher is out of his reach.

Five years later, they meet randomly and soon, Tim thinks he has never been happier. But amid family issues, war and prejudice, can they find the road to happiness together?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

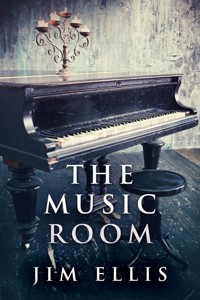

The Music Room

Jim Ellis

Copyright (C) 2018 Jim Ellis

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2019 by Next Chapter

Published 2019 by Next Chapter

Cover art by Cover Mint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Cynthia Weiner, Libby Jacobs, and Miriam Santana for their support and encouragement; and a warm thank you to Maggie McClure for proof reading. A special thanks to my Good Lady, Jeannette.

Well, honour is the subject of my story.I cannot tell what you and other menThink of this life…

Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, act 1

Chapter One: Apprentice Days

I was soon to be fifteen. I carried fantastic stories in my head. I held off the future dreaming of adventures in the Baltic Lands, imagined myself there fighting with Scots knights and mercenaries in the German service. And when I grew tired of that, I saw myself a Bronco Warrior, on the run with the last of the fighting Chiricahua. I was bored, but resigned to putting in the time until June. I wanted to be anywhere but St Mary's School. I dreaded what lay ahead when I left school: I wasn't going on the Baltic Crusade, or preparing to ambush the Cavalry; I was going down to Reid's foundry, a dirty noisy place where they built diesel engines for ships.

St Mary's was a school for boys, but on Sunday mornings at Mass I stared at the plump freckled girls. That helped shut out the soporific voice of the priest. Unexpectedly my life changed when I saw the new music teacher.

January 1954; the day school started after the Christmas holidays, the door of the music room clicked open and a lovely young woman came in. Her name was Isobel Clieshman. She was Springtime. I reckoned she was about twenty-three. She was lovelier than Hedy Lamarr or Joan Leslie, film stars I'd a crush on. Isobel Clieshman was real, and I wanted her to speak to me, but I'd have died had she. I felt so tender towards her; and guilty at the bulge in my pants.

There was hesitance in her walk; a movement of her sad eyes around the room. A look of regret that she had finished up in St Mary's and not some nice middle-class school in Glasgow.

To my class, she was 'The Proddy music teacher.' The verdict was 'Nae fuckin' tits.' For the wretched boys of St Mary's the pinnacle of female beauty was a fat arse and big knockers; a waspy belt pulled tight at the waist to give an hourglass shape. The boys lusted after Miss O'Hagen, a raven haired woman, run to fat. In her science class she talked about the body. She invited a boy to feel the pulse at her wrist; then squeezed her tit.

“The pulse beats in time to my heart.”

The boys loved it. I was glad I had Isobel Clieshman all to myself.

I adored the delicate points of her small breasts, the long slender legs. She arrived at the untidy time of school life, the end of Fourth Year. We loafed at our desks, idle, and impatient to be away from St Mary's. The music teacher was so different from the young Catholic teaching assistants, faces scrubbed pink, fresh from convent training where the nuns had wasted their heads with stories of Baby Jesus, The Blessed Virgin, and All the Saints. Miss Clieshman stood out from the sober female teachers shrouded in thick wool twin sets, tweed skirts, and sensible shoes.

I wondered what malfunction of fate had brought Isobel Clieshman to St Mary's. It was a bleak Catholic Technical School existing to feed boys to the doomed shipyards, foundries, and sugar refineries of the town. Sometimes she seemed so lonely, staring into space. I called her Cliesh and she belonged to me.

Most of the teachers in St Mary's looked down on the pupils. But from the start Cliesh showed an interest in us. In those few months, she taught us that there was more to music than bawling out hymns and sea shanties. We were surprised when she asked us to bring our records from home. Cliesh wanted to know where we'd bought them, and we told her about Saturday afternoons searching for bargains.

Someone handed over a record of Cauliga by Hank Williams and the class sang along with it.

“Cauliga was a wooden Indian standing by the door…” It was good fun.

“Did anyone else bring a record?” Cliesh said.

I'd got to the point where I had to do something or go mad. Cliesh displaced my dreaming of Baltic Crusades and Chiricahua life on the frontier.

The evening before the music class searching for courage I'd walked The Cut, an aqueduct inserted on the hills above the town. I meant to lay my heart bare and to Hell with the taunts of the class hard men that I was nuts and sucking up; or the possibility that Cliesh might reprimand me, then have James Malone thrash me for impertinence. It was crazy one way love.

I stuck up my hand; a smart arse. ”Bessie Smith, Miss.”

She listened to the introduction of Careless Love; it was an old record, the lyric muffled. Cliesh caught the tune on the piano.

“Tim Ronsard, will you sing?”

“Yes, Miss.”

The hard men tittered.

She played; I sang, voice pure.

“Love, oh love, oh careless love,

You fly to my head like wine,

You've ruined the life of many a poor man, and you nearly wrecked this life of mine…

Night and day I weep and moan…”

Cliesh fluffed a chord change and stopped the gramophone. She handed me the record, “Thank you, Tim. You've all been very good.”

I caught her eye and she turned away. Cliesh dismissed the class a few minutes early.

The next class Cliesh played the orchestral suite from Carmen and The Flying Dutchman on the gramophone. She barely looked at me. Then she played a selection from the Siegfried Idyll on the piano; I had to look away.

She asked me to stay behind after class and put away the gramophone. I didn't want to leave. “I'll clean the black board, Miss?”

“All right.”

I cleaned the blackboard slowly, perfectly.

“Where is your surname from, Tim?”

“Donegal, Miss.”

“You've heard of Ronsard?”

“No, Miss.”

“He was a French poet. Did you know your name was French?”

“No, Miss.”

We stood at her desk close to the piano. She wore a finely tailored jacket and matching skirt of soft heather and mustard wool; a white silk blouse tied at the neck with a loose cascading bow. She glided across the floor, slender legs in sheer stockings, elegantly shod. That day her lips were red and full, eyes heightened with touches of blue, the eyelashes long, and black.

Cliesh told me about the French who'd fought with the Irish rebels against the English in the Rising of '98. The ships of the French Navy that landed General Humbert's Black Legion. After parole and repatriation some of the French stayed on.

“Perhaps you're a descendant of a Naval Officer, or a legionnaire.”

“Oh, I wish that was true, Miss.”

Cliesh smiled. She'd made me proud of my name.

I was stiff with desire after being so near her. I ran into the yard, ready for home. I was ambushed by the class hard men: McAllister, Burns and Montague. McAllister grabbed my shirtfront, his face close.

“Whit the fuck dae ye want wi' tha' Proddy bastard?”

His teeth had green stains and his breath stank; his neck around the shirt collar was stained with tide marks. McAllister grabbed hard between my legs “Ah! Ronsard wants tae hump the Proddy. Cunt's got a fuckin' hard on; an' her wi nae tits.”

I pushed McAllister away. Burns came forward.

“Ronsard; whit kin' a fuckin' name is that? Cunt's a swank; 'mon we'll gie him a right fuckin' kickin'.”

There was a scuffle. Montague pushed me to the ground. James Malone, Depute Headmaster, stopped us and sent me to clean up. “I'll deal with you later,” he said.

I heard the drag of leather on cotton as Malone drew his Loch Gelly tawse hidden under the left shoulder of his jacket. The tawse: a quarter inch thick leather strap, two inches wide, and two tongues. Malone's was pliant and oily-soft from over-use. Leather cut air as he made a practice swing.

“Right, McAllister. Hands up. You're a waster, boy. You'll be in gaol soon.”

I got away before Malone changed his mind and decided to thrash me too. I knew the drill. McAllister, hands crossed, right hand uppermost, waiting. The smack of leather on flesh as Malone gave him 'Six of the Best.' Pupils had a choice. They could take it on one hand; after three blows, change to left hand. McAllister's hands would be numb and useless for a couple of hours. The palms beaten raw, a spider web of blood blisters spreading across his wrists. I'd no time for McAllister and his mates. They were thugs, but I hated Malone when he punished pupils.

I hid in the School Library. I'd a key given me by James Malone when he asked me to run it. I locked the door, unlocked the kitchen to the rear of the library washing the drying blood from my face, nursing my black eye, and bruised lip. I shouldn't have been there so late on Friday afternoon.

Footsteps thudded on the wooden stairs. The heavy tread of a man, the fluttering clicks of a woman's heels as she tried to keep up. The door to the library opened, I heard James Malone's voice and he had Cliesh with him. I eased the kitchen door open. James Malone, back to me, spread his arms.

“Come in, Miss Clieshman. You have not seen our room full of books.”

James Malone was a tough little man. He'd been under twenty when he won the Military Medal in France in the last month of the Great War. When he left the Army James Malone went to Glasgow University, winning a Double First in English and History. He dedicated his life to teaching. He was the cleverest teacher. A few of the staff respected him; many were in awe of him: the pupils feared him.

“Are you settling in?” James Malone said.

“Oh yes! I think so,” Cliesh said.

“Good. We have a library, and, at long last, a music teacher.”

Malone knew everything about St Mary's. He managed the school, patrolling the buildings and the grounds, gauging the mood of staff and pupils. He taught English and History. In the classroom, I often forgot that I feared him.

Before Cliesh came to the school, only James Malone showed any interest in us. His teaching was inspiring. He knew that a small group of Fourth-Year boys went to the cinema, and he would ask us about the films. Then he opened the door to the past. James Malone used The Grapes of Wrath to discuss the Great Depression, the New Deal, and American entry to the Second World War. When he knew that we'd just seen a Western, he'd describe the Frontier and Manifest Destiny. A dire film about Robin Hood and he told us about The Crusades and the peripatetic Scots knights and mercenaries hiring their swords to the Germans in the Baltic lands. I loved every minute of it.

“How is Fourth year doing?” Malone said. “It's a pity we do not have more time with them. They leave us when they are fifteen.”

“Yes, it's sad,” Cliesh said. They leave so young.”

“Ronsard looks after the library. I trust him. Last year he ran off all the exam papers for the school on the Gestetner.”

“Yes, I know.”

“He's fond of you, and when he sees you he's glad and embarrassed. But he's just a boy; when he can't see you, he's miserable.”

“Just what do you mean, Mr Malone?”

I cringed; there was a lump in my throat. My stomach shrank and the sweating started. I'd got her on James Malone's wrong side. Cliesh would hate me.

“Ah, Miss Clieshman. Don't be angry. You behave impeccably. It's hard for you, not among your own kind, and living away from home.”

“Will that be all, Mr Malone?”

“No, Miss Clieshman. I worked to bring you to St Mary's and I'd like you to stay. Not everyone in the school approves of a Protestant teacher; they'd have you removed.”

“I see.”

I wanted to strangle the teachers who hated Cliesh.

“Stay a moment. Ronsard has an injured face. Don't ask him what happened.”

I wanted James Malone to shut up.

“Was he fighting; is he all right?”

“Yes, but feeling sorry for himself.”

“What happened?”

“He objected to rude remarks the class hard men made about you. They attacked him. He blacked an eye and split a lip before he was knocked to the ground. That's when I stopped them.”

“That's awful, Mr Malone.”

“Miss Clieshman, the Age of Chivalry is not dead. It lives on in Young Ronsard; you must give him your beautiful silk scarf and tie it to the strap of his satchel. He is Your Champion.”

James Malone stifled a chuckle. It was hard to listen to him and Cliesh. The back of my shirt was wet. I blushed, face burning; felt a fool. My heart raced and thumped in my ears like a cannon on automatic. Cliesh and James Malone must hear it. I didn't give a shit about Malone, but how could I face Cliesh after this?

I stayed in the kitchen for another half hour to be sure they'd left the school. There would be trouble when my mother saw I'd been fighting. I walked home with an aching face and a sore heart.

The headmaster invited Cliesh to form a small choir to sing at the prize giving. I joined along with a few others. The weeks until the summer break merged as we rehearsed. The choir met most days and on some Sundays. I wanted to sing for her and see her.

Cliesh changed with the season. Summer was the time of her opening. She wore light dresses of delicate red and yellow, her hair flowing as she let it down, or, bound loosely with a wisp of silk. She was at ease, her features gentle and beautiful. It was joy to be near her.

Loving Cliesh made me careless. I dreamt about her every day. I was idle in the woodwork class, toying for weeks making a wooden crucifix, staring into space, and thinking about the clothes Cliesh wore, the tailored jackets and skirts, the sheer stockings, her shapely legs, and the elegant shoes, I went into forbidden territory and thought about her delicate breasts and more. Lust blotted out guilt.

A hard hand hit me twice on the back of the head.

“You're useless, Ronsard,” the woodwork teacher said. “Plain lazy. Hands up.”

The bastard gave me six of the best with his Loch Gelly. My hands were raw and numb. He wanted me to cry, but I kept staring at him, thinking fuck you.

“Get out of my sight,” he said.

I walked home, suffering for love nursing my sore hands, rubbing life into numb fingers, bruised palms and wrists, whispering “I did this for her.” I was crazy.

I sat at the kitchen table and wrote Cliesh in Gothic letters in my notebook. I drew a heart round her name, and pierced it with arrows. My mother picked up the notebook and shook her head.

“Who's that? I hope she's a Catholic. You're a soft lump, Tim Ronsard. You see and behave your self.”

I tried not to think of leaving school at the end of June. I devoted myself to rehearsals.

The audience liked the songs. The enthusiasm for Handel's Where're you Walk was unexpected. Everyone loved I Met Her In The Garden Where The Praties Grow. The chorus stayed with me.

She was just the sort of creature, boys,

That nature did intend

To walk right through the world, me boys,

Without a Grecian Bend.

Nor did she wear a chignon,

I'd have you all to know.

And I met her in the garden

Where the praties grow.

I sang for Cliesh from my heart.

She shook hands with each one of her boys that last day and said farewell. I held onto her hand, and saw affection in her eyes. Cliesh's fondness crushed me; I'd wasted my love, my dreams broken glass. School days were over.

I left school and started work at Reid's foundry. My parents were very pleased. I was not. Discontent began in the Apprentice School.

Each morning I walked through the machine shop, deafened by screeching lathes, drilling, and milling machines and overhead whining crane motors. The stench of cut steel and cast iron flying from tool points; sparks shot off grinding wheels. I could barely stand the noise; the stink of machine suds spraying on hot metal jolting me awake. From day one, I hated Reid's.

The sole consolation at work was my friendship with Sam Minto. Sam was small and thickset, with a low centre of gravity. I was gangly, all arms and legs. We were awkward in our hand-me-down shabby adult clothes.

The School lasted three months. There were twelve apprentices. We spent our days inside a wire-mesh cage lit by blue arc lights, working at benches made from chequered engine plate, vices set on the edge. There was a lathe, two small drilling machines, a milling machine and an engraving machine on the floor. For one week each apprentice cleaned the urinals at the end of the workday. The place reeked of piss, disinfectant and lube oil.

The classroom was at the back of the School. We were instructed in basic engineering skills, elementary mathematics, using hand tools and calibrated tools. Instruction was crude. Apprentices bashed hands, lacerated knuckles, and mashed fingers hammering, chiselling, filing. The School was a grim chapter of bruised fingers, cut hands, chipped, filthy nails: in a week my fine hands and long fingers became coarse engineer's fists.

And the routine humiliation. Willie Cain, Supervisor, and Joe Tolly, Charge Hand, governed the School. Cain a small corpulent man in a three-piece suit and stained felt hat that was his badge of office. I dreaded his approach, puffing on Turkish cigarettes watching me work. Cain had been a star apprentice and he never missed an opportunity to preach the benefits of an apprenticeship in Reid's.

“Ye can achieve anything,” he said.

Cain held up a small electric drilling machine and an automatic centre punch for our admiration. I can see Cain yet, gloating over his achievements. “Ah made these masel' when ah wis your age.”

Cain had spent years working with boys. Outside the foundry he was a Captain in the Boys Brigade, a quasi-military organization for Calvinist boys. Cain should have inspired all apprentices, but had become a Career Protestant.

Tolly looked after hands on training. He was a sour wee man in a brown overall and a large flat cap. Often there was an overpowering smell of stale whisky from his breath. Sam and I figured the pair of them had been confined to the School to keep them from the real business of the foundry.

Cain and Tolly acted from deep conviction: they would do what was necessary to mould young minds. Most apprentices did not fight back. Boys averted their eyes, as Cain or Tolly berated some wretched apprentice for a minor infraction.

“See you, ya wee bastard. Ye should have been a fuckin' butcher. Then, ye could eat a' ye scrapped.”

They threatened anyone caught looking. “Whit the fuck are ye lookin' at? Huv ye no' enough tae dae? Ah'll soon find ye somthin'.”

Humiliation was routine in the classroom. Catholics and Protestants who were friends got the treatment. I was the token Catholic and Sam was the renegade who befriended me. We dreaded lessons in the use of the Micrometer and the Vernier gauge. Cain would light a Turkish cigarette.

“Ronsard! Can ye no' count? Whit the fuck did they teach' ye in St Mary's?”

Then he'd turn on Sam. “You, Minto! Yer a fuckin' disgrace; a right disappointment. Did ye no' go tae the Mount School? Keep back fae him and get on wi' yer work.”

It was hard to cope with these onslaughts. Adolescents plagued by acne, clumsy movements, too many hormones and worst of all, sudden intense blushing.

Cain and Tolly believed that they could transform unpromising youths into useful employees. Often they were right. A few miserable boys resisted but surrendered in exchange for a measure of peace. I overheard Cain. “Aye, Joe. They'll know their stuff when we're done wi' them. We'll huv remade their heids.”

“Aye; right enough, Boss.”

Cain and Tolly couldn't manage apprentices. It had never dawned on them that a word of praise, a gesture of recognition, the faintest smoke signal of generosity might have altered things in their favour and brought all the apprentices to their side. Cain and Tolly were experts at remaking heads, and knew how to deal with hard cases.

Working for Cain and Tolly was misery, and there was no sympathy at home. Our parents felt that getting an apprenticeship at Reid's was a privilege. They had no idea what it was like in the Iron Cage. We learnt to rely on ourselves; Sam and I were the last two resisting.

I liked the Chiricahua Apache. I told Sam about their bravery and we tried to be like them, Bronco warriors, defiant and out of control. But our counter attacks were feeble.

When Cain and Tolly were working in the classroom we hurled two-foot long inch square files twenty feet into the roof space, burying the tang into the wooden supports. We told Tolly we had the shits and vanished into the disgusting jakes for ten minutes reading comic books.

Cain and Tolly used the job to punish us. There was no justice in that place. Had we been smart, we'd have conformed and Cain and Tolly might have lain off. But we were not smart. It went against the grain to conform and we fought on. Our strongest defence was dumb insolence and delay. Sam was last-but-one to finish the trades test. I was last. Sam ruined a valuable brass nameplate by cutting in a period not on the drawing. Tolly gushed his stale whisky breath over Sam's face.

“Fuck off, Minto! Yer bloody useless.”

Sam shrugged and walked back to the workbench.

One morning Cain ambushed me. I was filing a brass nameplate to shape. Cain thrust a Turkish cigarette into the corner of his mouth and lit it. “That looks like a fuckin' sausage. Too bad ye canny eat the fuckin' thing.” The master craftsman wrenched the file from my hand.

“Why don't ye' just finish it?” I said.

Cain's jaw dropped. He almost lost his cigarette, and he lost the place. “Another fuckin' word oot o' ye and yer suspended fur a week. Ah've a good mind tae sack ye.”

He thumped me on the chest with the back of his right hand. Tolly looked on, a vicious grin spreading over his boozy old face. The threat of suspension or the sack subdued me; not that I gave a shit. It was the row at home that terrified me. My mother would take me apart and complain to my father. “Whit are we gonny dae wi him? He's right oot o' control.”

And Tolly let us know who was boss. It was Sam's turn to clean the urinals. “A fuckin' disgrace. Dae them again,” Tolly said.

I was waiting on Sam to finish. Tolly turned the screw on me. “You! Gi'e him a hand.”

It was a wet night, and we missed our bus. It was a long walk home; we dragged our heels over black pavements, slouching in and out of circles of light from the street lamps. “Let's get that fucker, Cain and that cunt, Tolly,” I said. Sam smiled.

I hadn't forgotten Cliesh, but I'd given up hope of ever seeing her again. How could a daft apprentice find her? Because of Cliesh I loved music. One night I came out of a cinema where I'd watched Carmen Jones. My head was full of the beautiful Dorothy Dandridge.

“Tim! Tim Ronsard.”

My eyes locked onto Cliesh's eyes; Oh Sweet Jesus, just to see her. I felt my face reddening and looked away. She was lovelier now. I wanted to impress her, say something that would make her laugh, but I could hardly breathe.

“Hello, Miss Clieshman, how are you?”

Cliesh was dressed in a light wool coat, belted at the waist, a beige silk scarf knotted sailor fashion at her neck. She was statuesque in her elegant heels. I shook her gloved hand awkwardly.

“I'm fine, Tim. I'm so pleased to see you. Walk with me. Tell me how you've been getting on.”

I told her that I was an apprentice in Reid's foundry and she picked up how unhappy I was. I made a few shy remarks about the film.

“I turn here, Miss.”

“Come and have coffee, Tim. Come on Sunday afternoon. Let's say two o' clock?”

“That'd be nice, Miss.”

The days dragged until the weekend. On Saturday I bought a cheap razor, soap and a brush for my first shave. I pressed my Sunday clothes and polished my shoes. On the Saturday night I walked the streets to save money. I wanted to bring her a small present.

Sunday morning I got out the new shaving kit.

“Will ye look at him shavin'. You're no goin' tae visit a teacher; you're meetin' some lassie.” My mother didn't want me to grow up. I ignored her.

I appeared at Cliesh's door promptly. I was smart in suit and white shirt and one of my father's sober ties. But I was awkward standing at her door clutching a small box of chocolates wrapped in brown paper.

Smiling, Cliesh undid the wrapping. “Thank you, Tim. How thoughtful of you. I love Terry's chocolates.”

We had tea, chatted pleasantly about school, and my apprenticeship. She glanced at the chipped, begrimed nails, the deep, unhealed nicks, and the cut finger joints; the ingrained dirt, and one nasty gash on the heel of my right hand.

I could've stayed until midnight, but had to be home by six.

“Will you come next Sunday, Tim?”

“Oh, yes. I'd like to come.”

I took the long way home stopping at the old reservoir, staring into the dark water until Cliesh's face appeared. I'd never been happier.

I loved the Sunday afternoon visits to Cliesh: the bright coal fire; the copper and russet of autumn trees, visible from her windows; the late roses and Icelandic poppies bunched in vases on the sideboard. Her living room was comfortable. Stuffed sofas in front of an Adam fireplace, a copy. Heavy wallpaper brought the walls closer. A plaster cornice of duck eggs picked out in delicate blue. Mogul Miniatures of dancers and courtesans hung on the walls. The largest picture was a copy of Burmese Girls, by Russell Flint. The floor was dark varnished wood, a few oriental rugs placed advantageously, one of them a gorgeous Hatchli. In one corner there was an upright piano, a Petrof finished in deep polished rose wood. When she told me about the furnishings, the carpets, and the paintings, my love for her grew.

When my father was away at sea on the Irish boats there was a death chill between the Old Lady and me. She was sore that I hated working at Reid's, and she resented that I was growing away from her.

By mid-week I was fed up and Sunday, seeing Cliesh, was out of reach. To get to the cafe for a few hours I wound myself up to ask my mother for the price of a soft drink.

“Yer out far too much. Ye spend yer pocket money at the weekend. Dae you think I'm made o' money?”

I'd read and brood in my bedroom. But satisfied that she'd drawn blood she'd hand me a shilling or two to get rid of me, yelling as I went out the door. “See and get back here at a decent hour.”

In the cafe, I'd nurse a Coke or an orange juice and think about Sunday.

I wanted to believe that Cliesh looked forward to the visits as much as I did. Did she grow fond of me? She seemed to dress to please me. I would wait for her to open the door listening for the faintest sound of her footsteps. Each time I longed to see her, catching her fragrance. The textures of that autumn were silk and wool: silk blouses, and scarves holding her hair back. Then I could see her small delicate ears. Cliesh loved simple wool dresses and skirts that showed off her slender legs. I could not keep my eyes from them and she caught me looking. I loved her beautiful legs.

They were innocent Sunday afternoons. We drank a small glass of Sherry. Then she played the piano. She was fond of Ravel, Debussy, and Poulenc. But her delight was Albeniz. She played selections from Iberia with spare, erotic passion.

Cliesh served afternoon tea; small cucumber sandwiches, or sardines on toast. She infused Darjeeling, Lapsang Suchon or the strong dark leaf from the Nilgris Hills. Near the end of the afternoon before I left, she brewed Kenyan, Java, or Columbian coffee. I loved that last half hour sitting with her, nursing a china cup and already looking forward to the next Sunday.

We often exchanged shy looks. When we talked she lowered her eyes suggesting innocence and invitation. Our hands touched as she offered plates, and glasses or cup and saucer. Sometimes, her long, cool tapered fingers, with the polished nails, would linger on mine.

She didn't know that I called her Cliesh. I'd not the nerve to call her Isobel. I managed to avoid calling her Miss Clieshman. When I had to I called her Miss.

Her clothes flattered her slim figure and small delicate breasts, the long slender legs; god, she was sexy. I desired her and felt guilty. She was so far above me and I adored her. One Sunday she sat beside me as we had afternoon tea.

“I like Sunday afternoons, Tim. I like being with you.”

I nodded; not sure how to respond.

“Do you like coming to my rooms?”

“Yes.”

“You know, Tim, it's not easy teaching music at St Mary's. The teachers; oh, some of them mean well. Polite and all, but they're not warm. I don't feel I belong.”

The room was quiet, the coals in the grate hissing and cracking; wavering fingers of yellow flames casting shadows.

“I'm looking for another job. There must be schools that respect music. You know I give piano lessons?”

“Yes.”

“I have a little money of my own. That helps.”

She was making me miserable. I prayed. “Please, please don't let her leave.”

“I loved the choir. You and the other boys, so open and friendly. You changed with me. It was so sweet, the way you sang.”

“I liked the choir.”

“What was I called in school; what was my name?”

“Miss Clieshman.”

“Really?”

“They called you The Proddy; The Proddy music teacher.”

The vexed look on her face; not that I meant to, but I'd cut her to the quick.

“And you, Tim. What did you call me when you thought about me?”

I shrugged; think about her? All day every day; I flushed a deep shade of pink, “Cliesh.”

“Is that my special name ?”

“Yes.”

“Tim, Tim, that's so lovely.”

Westburn men kept tenderness out of their lives. They talked about humping, shagging, or fucking. But not love; not being in love. I'd never heard a woman speak of the heart. Perhaps when they're alone women talk about it. Love was scant in Westburn.

My love could have brought a photograph of Cliesh to life. But I was chained to the hard words of my people. I couldn't say what I felt for her. How could I tell Cliesh that I loved her?

Her fingers left warm tracks on my face. I was going crazy, a lump in my throat, swallowing, fighting tears. How could Cliesh ever love me, awkward, gangly, acne scars newly healed?

Cliesh dried my eyes. “Oh, Tim my sweet boy; I love you; I love you very much.”

I knew it was all right. “I love you.”

She smiled, radiant; sweet laughter. ”I know, Tim; and I do love you.”

The best words I'd ever heard.

We sat on the edge of her bed.

“It's my first time.”

“I know, I know, Tim.”

Then a lingering kiss, her tongue opening my lips.

“My shoes, Tim. Help me with my shoes.”

I caught her smell on her new-worn shoes. I wanted her breath, her body, and her secrets. I came in her hand.

“Oh, Tim!”

I lay with Cliesh and she gave me what I longed for. We didn't undress. We lay together half-undone. Cliesh sensed my next shudder and her stockinged feet brought me closer, then she held me with warm, firm fingers, startling me.

“Touch me. Like this, Tim. Wait for me.”

We crossed a frontier when we became lovers. Sundays changed. Cliesh eagerly opened her door and once inside her rooms, we kissed and touched. Some Sundays, we were so glad to see each other after a week apart, that we made love at once. After we'd drunk coffee, just before I had to leave, we made love, again, tenderly.