6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

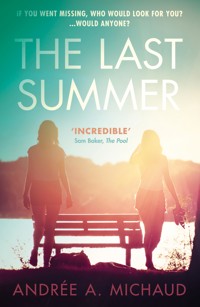

**Winner of the Governor General's Award for Fiction 2014 Winner of the Prix des Lecteurs at the Quais du Polar for Best French Crime Novel 2017 Winner of the Prix du Conseil des Arts and des Lettres de Quebec for Book of the Year 2015 Winner of the Prix Saint-Pacôme for Best Crime Novel 2014 Longlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize 2017 A chilling thriller as compulsive as Emma Cline's The Girls. It's the Summer of 1967. The sun shines brightly over Boundary lake, a holiday haven on the US-Canadian border. Families relax in the heat, happy and carefree. Hours tick away to the sound of radios playing 'Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds' and 'A Whiter Shade of Pale'. Children run along the beach as the heady smell of barbecues fills the air. Zaza Mulligan and Sissy Morgan, with their long, tanned legs and silky hair, relish their growing reputation as the red and blond Lolitas. Life seems idyllic. But then Zaza disappears, and the skies begin to cloud over... (Originally published in the UK in hardback and trade paperback as Boundary)

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

The Last Summer

It’s the Summer of 1967. The sun shines brightly over Boundary lake, a holiday haven on the US-Canadian border. Families relax in the heat, happy and carefree. Hours tick away to the sound of radios playing ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’ and ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’. Children run along the beach as the heady smell of barbecues fills the air. Zaza Mulligan and Sissy Morgan, with their long, tanned legs and silky hair, relish their growing reputation as the red and blond Lolitas.

Life seems idyllic.But then Zaza disappears, and the skies begin to cloud over…

About the author

Andrée A. Michaud is a two-time winner of the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction (Le Ravissement in 2001 and Bondrée in 2014) and the recipient of the Arthur Ellis Award and the Prix Saint-Pacôme for Best Crime Novel for Bondrée (The Last Summer), as well as the 2006 Prix Ringuet for Mirror Lake (adapted for the big screen in 2013). Bondrée also won the Prix du Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec for Book of the Year 2015 in Eastern Townships and the Prix des Lecteurs for Best French Crime Novel at the Quais du Polar 2017. As she has done since her very first novel, Michaud fashions an eminently personal work that never ceases to garner praise from critics and avid mystery readers alike.

PRAISE FOR THE LAST SUMMER

‘Atmospheric and unnerving… award-winning French-Canadian crime writer Andrée Michaud is my new crack’ – Sam Baker, The Pool

‘While it has an element of the whodunit, this lushly written, award-winning francophone novel is literary crime-writing in which the texture of period and place takes priority’ – Sunday Times

‘Brilliantly innovative in narrative and thrillingly readable… a splendid novel that makes high literature out of crime and suspense’ – Robert Olen Butler, Pulitzer Prize winner

‘Haunting in its simplicity… like the wood in the novel, it swallows you up’ – The Book Trail

‘Both intelligent and careful… a quietly considered, beautifully descriptive novel that looks at the devastating effect of tragedy on a community’ – Jaffa Reads Too

‘A slow burn of a tale with an edgy sense of place – I was extremely taken with this story, and it stayed with me’ – Liz Loves Books

‘A spectacular book… exhilarating. I feel reel enriched and rewarded as a reader from the experience’ – Reflections of a Reader

‘A truly atmospheric and captivating novel… one which slowly and quietly seeps into your consciousness. A book which will, on some level, haunt me for some time to come’ – Jen Meds Book Reviews

‘Michaud transcends the limitations of the crime genre’– L’Actualité

‘The writing is fiery and inspired’ – Le Devoir

‘Michaud has an undeniable talent for penning riveting and effective thrillers’ – Le Droit

‘The novel flirts with the thriller genre while toying with its rules’ – Les Libraires

To my father

Bondrée is a place where shadows defeat the harshest light, an enclave whose lush vegetation recalls the virgin forests that covered the North American continent three or four centuries ago. Its name derives from a deformation of the word “boundary,” or frontier. No borderline, however, is there to suggest that this place belongs to any country other than the temperate forests stretching from Maine, in the United States, to the southwest of the Beauce, in Québec. Boundary is a stateless domain, a no-man’s land harbouring a lake, Boundary Pond, and a mountain the hunters came to call Moose Trap, after observing that the moose venturing onto the lake’s western shore were swiftly trapped up on the steep slope of this rocky mass that with the same dispassion engulfs the setting suns. Bondrée also includes several hectares of forest called Peter’s Woods, named after Pierre Landry, a Canuck trapper who settled in the region in the early 1940s to evade the war, to flee death while himself inflicting it. It’s in this Eden that ten or so years later a few city-dwellers seeking peace and quiet chose to build cottages, forcing Landry to take refuge deep in the woods, until the beauty of a woman called Maggie Harrison drove him to return and roam around the lake, setting in motion the gears that would transform his paradise into hell.

The children had long been in bed when Zaza Mulligan, on Friday 21 July, stepped onto the path leading to her parents’ cottage, humming A Whiter Shade of Pale, flung out, in the bedazzlement of that summer of ’67, by Procol Harum, along with Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. She’d drunk too much, but she didn’t care. She loved seeing objects dancing about her and trees swaying in the night. She loved the languor of alcohol, the odd gradients of the unstable ground, forcing her to lift her arms as a bird unfolds its wings to ride the ascending winds. Bird, bird, sweet bird, she sang to a senseless melody, a drunken young girl’s air, her long arms miming the albatross and those birds of foreign skies that wheel over rolling seas. Everything around her was in motion, all charged with indolent life, right up to the lock on the front door into which she couldn’t quite manage to insert her key. Never mind, because she didn’t really want to go in. The night was too lovely, the stars so luminous. And so she retraced her steps, crossed back over the cedar-lined path, and walked with no other goal than to revel in her own giddiness.

A few dozen feet from the campground she entered Otter Trail, the path where she’d kissed Mark Meyer at the start of summer before going to tell Sissy Morgan, her friend since always and for evermore, for life and ’til death do us part, for now and forever, that Meyer frenched like a snail. The slack memory of that limp tongue wriggling around and seeking her own brought a taste of acid bile to her throat, which she fought off by spitting, barely missing the toes of her new sandals. Venturing a few awkward steps that made her burst out laughing, she moved deeper into the woods. They were calm, with no sound to disturb the peace in that place, not even that of her footsteps on the spongy earth. Then a light breath of wind brushed past her knees, and she heard something crack behind her. The wind, she said to herself, wind on my knees, wind in the trees, paying no heed to the source of this noise in the midst of silence. Her heart jumped all the same when a fox bolted in front of her, and she started laughing again, a bit nervously, thinking that the night gave rise to fear because the night loves to see fear in the eyes of children. Doesn’t it, Sis, she murmured, remembering the distant days when she tried with Sissy to rouse the ghosts peopling the forest, that of Pete Landry, that of Tanager, the woman whose red dresses had bewitched Landry, and that of Sugar Baby, whose yapping you could hear from the top of Moose Trap. All those ghosts had now vanished from Zaza’s mind, but the sky’s moonless darkness revived the memory of the red dress flitting through the trees.

She was starting to turn off onto a path that intersected with Otter Trail when there was another crack behind her, louder than the first. The fox, she said to herself, fox in the trees, refusing to let the darkness spoil her pleasure by unearthing stupid childhood terrors. She was alive, she was drunk, and the forest could crumble around her if it wished, she would not shrink from the night nor the barking of a dog that had been dead and buried for ages. She began to hum A Whiter Shade of Pale among the swaying trees, imagining herself in the strong arms of someone unknown, their dance slow and amorous, when she stopped short, almost tripping over a twisted root.

The cracking came closer, and fear, this time, began to steal across her damp skin. Who’s there, she asked, but silence had fallen upon the forest. Who’s there, she cried, then a shadow crossed the path and Zaza Mulligan began to retreat.

PIERRE LANDRY

I remember Weasel Trail and Otter Trail, I remember Turtle Road, Côte Croche, and the loons, the waves, the docks suspended in mist. I’ve forgotten nothing about the Bondrée forests, and their green so intense that it seems today to have emerged full-blown from the radiance of a dream. And yet nothing is more real than those woods where the blood of red foxes flows still, nothing is truer than the fresh water in which I swam long after the death of Pierre Landry, whose presence in the heart of those woods still haunted the surrounding area.

Many stories circulated concerning this man who it was claimed lashed out with a mystifying rage, stories of bestiality, savagery, and madness, all to the effect that Landry, rejecting the war, had signed a blood pact with the forest. Some drew on these absurd legends to explain why Landry had hanged himself in his shack, but the most plausible version spoke simply of a love story and a woman Landry called Tanager, associating her red dresses with the flight of those scarlet birds. Recollections of this woman, whose name was linked inexorably to that of Landry, had bit by bit worked their way into Boundary’s collective memory. She had become a ghost to whom children cried out at dusk as they stalked the shadows dancing on the shore. Tanager, they whispered, fearful, Tanager of Bondrée, hoping to see the silhouette of this bird woman, born of a few shreds of red silk tossed together in Landry’s deranged mind, rise from the thin fog licking at the shoreline. I dared not, myself, conjure Tanager, fearing in my own muddled way that her ghost might materialise before me and give chase. I preferred, perched in a giant tree, to watch for the spectacular emergence of the tanagers in Bondrée’s dense forest cover, barely compromised by the construction of the road leading to the lake.

It was that road, they said, which had forced Landry to retreat deep into the woods, a road soon followed by cottages, and then the men, the women, the voices seconding the din from shovels and motors. Soon after these disturbances, patches of colour appeared in the still-virgin landscape, creating a small enclave where for a few months each year the colour took on life, to encroach on the greenery at the heart of which Landry had established his derisory empire.

Despite the relatively small number of vacationers, the human presence, while it lasted, detracted from the wildness of that place. From the beginning of June doors began to slam, radios to crackle, and sometimes you heard a child cry out that he’d caught a minnow. But it was in July that Bondrée really came alive, with its share of teenagers, tired mothers, pets, and family vehicles so loaded down with belongings that you could almost see them sending off fumes at the last turn onto Turtle Road, the gravel road circling the lake, which followed, it was said, the trail marked out by the slow exodus of turtles come from ancient rivers. All those people who were jolted along Turtle Road formed a mixed community of English speakers and French speakers from Maine, New Hampshire, or Québec, living side by side and barely talking to one another, often content with a wave of the hand, a bonjour, or a hi!, signalling their differences, but acknowledging the bond they shared in this place they’d chosen to assert their remote connection to a nature that excluded them.

As for us, we arrived right after the Saint-Jean Baptiste holiday and the end of classes, whatever the weather. That summer, however, my father treated us to three days of rides, cotton candy, hot dogs, and space travel at Expo 67, before, our heads crammed full of Africa and Sputniks, we got on the road for Bondrée and the familiar rituals that awaited us, without which no summer would be worthy of the name.

They never changed, and smacked of a freedom known only to a life that’s free from care. While my parents unloaded the car, I went down near the lake to drink in the smells of Bondrée, a mix of water, fish, sun-warmed conifers and wet sand, along with the slightly mouldy odours that permeated the cottage right into September despite the open windows, the aromas of steak and fruit pudding, and the pungent perfumes of the wildflowers my mother gathered. Those odours, which lasted from June until the nights grew cool, have no equal beyond the wetness in the air when it comes to unearthing my childhood memories, shot through with green and blue, with grey overtopped by foam. They are the custodians, beneath sunlit surfaces, of those summers’ humid essence during the years when I was growing up.

I was only six years old when my parents bought the cottage, built from cedar logs and surrounded by birch and spruce that shaded a windowed room from which we could admire the lake. That’s why they’d acquired the property, for the veranda and for the trees that gave them renewed access to a utopian dream that life had taken from them. They were only twenty years old when my brother Bob was born, twenty-three when I arrived, twenty-eight when Millie came on the scene, and even if they weren’t old their idea of happiness had contracted, had been reduced to a veranda and a cockeyed garden where parsley and gladioli grew pell-mell.

I knew nothing of those dreams that had vanished along with my mother’s virginity, dreams sacrificed to the scrubbing of diapers and the many unpaid bills piled up on my father’s desk, squeezed into a corner of the living room. I didn’t realise that my parents were still young, that my mother was beautiful, that my father laughed like a child when he could forget that he had three offspring of his own. Saturday mornings he jumped onto his old bicycle and did the tour of the lake in more or less forty minutes. My mother timed him, watched him dart through the trees and take the turn at Ménard Bay, and she gave a yelp of victory if he beat his own record. Thirty-nine minutes, Sam! she exclaimed with a delight whose ardour escaped me, because I didn’t know that my father was an athlete converted to hardware, and that he could have left in the dust that handful of adolescents coming down Côte Croche, Snake Hill to the English, feet perched on the handlebars of their bicycles, trying to impress the girls.

My parents’ lives began with me, and I couldn’t conceive that they had a past. The little girl posing in black and white on photos stored in a Lowney’s chocolate box that served as our family album didn’t at all look like my mother, no more than the boy with the shaved head chewing on a wisp of hay near a wooden fence looked like my father. Those children belonged to a universe that had nothing to do with the adults whose immutable image kept the world on its steady course. Florence and Samuel Duchamp’s entire purpose in life was to provide, to protect, and to impose limits. They were there and would always be there, familiar figures for whom I was their only reason to be alive, along with Bob and Millie.

It was only that summer, when things got out of hand and I began to lose my bearings, that I came to see that the frailty of those little people shut up in the Lowney’s chocolate box had endured down the years, along with the fears buried at the heart of every childhood, fears that resurface as soon as it becomes clear that the world’s solidity rests on a foundation that can be swept away with a single gust from an evil wind.

Sissy Morgan and Elisabeth Mulligan, called Zaza, the two girls who would prove to be the conduits for this calamity, were still only children when we moved to Bondrée, but they were already inseparable, Zaza always dressed like Sissy, and vice versa. You would have thought they were twins, one head red and the other blonde, tearing down Snake Hill crying Sissy, look! Run, Zaza, run! pursued by who knows what creature making them race until they were out of breath. Run, Zaza, run! My mother called them the Andrews Sisters, even if there were three Andrews Sisters and they sang a hundred times better than Sissy and Zaza.

My mother, whose maiden name was Florence Richard, loved everything old-fashioned, including the Andrews Sisters, and sometimes she even tried dancing to Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy. In the rare moments when she let herself go with what seemed to me a sort of exhibitionism, I did my best to remove myself as far as possible from the Andrews Sisters’ voices crackling away on the old cottage turntable, because I was ashamed to see my mother showing herself off. Dancing was not for mothers. Nor was youth. They were only for the LaVernes, the Maxines, and the Patty Andrews, for the kind of girls Zaza Mulligan and Sissy Morgan would become, like Denise Lachapelle, one of our neighbours in town, who dressed provocatively and had loads of friends who came by to pick her up on Saturday night in their convertibles or on their motorcycles, Kawa 750s that roared away in the mild air and made my father envious, he who couldn’t even afford to replace his old ’59 Ford.

Sissy and Zaza were for me Denise Lachapelles in the making who would turn boys’ heads and paint their faces on Saturday night. But for most people they were only spoiled children, spoiled rotten in fact, obnoxious kids for whom nothing was out of bounds, tilting whichever way the wind blew, goading each other on, and riding for a fall. Not bad seeds. Just wild plants, that’s all, whose weakness for the sun you could do nothing about. I would have loved to be the one to turn their duo into a trio, but they wouldn’t have anything to do with a little twerp four or five years younger than they were, trying to impress them with her collection of live insects or by catching toads. Yuk! they cried, is this your brother? Then they burst out laughing and gave me a candy or some bubble gum because they found me cute. She’s so cute, Sis. And they took off and left me with my toad, my grasshoppers, my crickets, and my treats. Sometimes I asked my mother the meaning of “frogue,” “foc,” or “chize.” “Fromage,”cheese, she replied, with her smile widening around the word “cheese,” and she executed a mother’s pirouette over the word “foc,” a wimpish pirouette that didn’t risk hoisting her skirt up over her thighs. She gave me a lesson on “phoques,” or seals that lived at the North Pole and spoke Eskimo, anything at all, answers for big people, adults, who’d forgotten how much a word divorced from its meaning can unsettle a childhood.

I never ate the candies. I put them away in my treasure chest, a rectangular tin box decorated with a Christmas tree, and also containing stones, feathers, twigs, and snakeskins. I did, however, save the bubble gum for special occasions, when I’d just spotted a raccoon rummaging in a garbage can, or a trout snagging a fly on the surface of the lake. The smallest rabbit dropping stuck to my red running shoes became a pretext to run and hide under a Virginia pine whose branches touched the ground, a shaded space I called my cabin, where I unwrapped the bubble gum, repeating here, a baby yum for you, littoldolle. With my tomboy air I was anything but a doll, but I was proud of projecting an image in the eyes of Bondrée’s two most fascinating creatures, grasshoppers and salamanders included, as perfect as their gilded universe. I squeezed the baby yum with my fingertips until it was nice and soft, and stuck it to my palate with a smile: here, littoldolle. Those globs of bubble gum were in some sense the ancestors of the Pall Malls I would later crave, the distinctive trademark of Sissy and Zaza, who were able to pop enormous bubbles without ever having them stick to their faces. In my cabin I practised bursting bubbles like you practise blowing smoke rings, then I buried the gum under pine needles and went back to the lake, to the squirrel paths, to everything that then delighted me, to those simple things rich with odours that would later help me to resuscitate my childhood and renew contact with a simple joy every time a rustling of wings stirred up a scent of juniper.

The last summer we spent at Bondrée was, however, suffused with another odour, one of flesh, both sex and blood, which rose from the humid forest when night fell and the name Tanager echoed on the mountain. But nothing hinted at that tenacious perfume when the campfires, one by one, were lit around the lake, those of the Ménards, the Tanguays, the McBains. Nothing seemed able to cloud the sunstruck indolence of Boundary, because it was the summer of ’67, the summer of Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds and the Montreal World’s Fair, because it was the summer of love, as Zaza Mulligan proclaimed while Sissy Morgan lit into Lucy in the Sky and Franky-Frenchie Lamar, with her orange hula-hoop, danced away on the Morgans’ dock. July offered up its splendour, and no one suspected then that Lucy’s diamonds would soon be reduced to dust by Pete Landry’s traps.

The springing of those traps resounded as far as Maine, because Zaza Mulligan and Sissy Morgan, who were considered the sort of girls to be forgotten after one night, would soon brand Bondrée’s memory with a red-hot iron. In the process, they demonstrated that people like Pete Landry, bound too tightly to the woods, never quite died. Like Landry, they headed down the tortuous paths of a forest well-trodden by man to become legends in their turn, in tales where the redhead and the blonde would in the end be confused, since there where you saw Sissy, you were sure to encounter Zaza. The urchins of the time even made up a silly song they chanted to the tune of Only the Lonely every time the two girls flounced by, but what did they care, they were Boundary’s princesses, the red and blonde Lolitas who’d made men drool ever since they’d learned to draw their gaze with their well-tanned legs.

Most of the women didn’t like them, not only because they’d one day or another caught their husband or fiancé ogling Zaza’s navel, but because Sissy and Zaza didn’t like women. Zaza tolerated only Sissy, and vice versa. The others were just rivals whose potential for seduction they appraised, elbowing each other and sniggering. Neither did the men like those girls, who seemed to have no better goal than to excite in them what they thought only lurked in other men. They were for them just fodder for their fantasies, conjuring the worst obscenities, Zaza with her thighs spread wide, Sissy on her knees, cock-teasers they would discard along with their Kleenex, ashamed, when their wives called them in for supper, of having behaved like all other men.

So they weren’t surprised to learn about what happened to them. Those girls had been asking for it, that’s what most of them couldn’t help thinking, and those thoughts sparked in them a kind of treacly remorse that made them want to pound themselves with their fists, to slap themselves until they drew blood, because the girls were dead, good God, dead, for Christ’s sake, and no one, not them nor anyone else, deserved the end that had been reserved for them. It took this calamity for them to think of those girls as anything but schemers, for them to understand that behind their rancour was only a vast emptiness into which they’d all stupidly thrown themselves, seeing nothing but the tanned skin camouflaging that emptiness. If life had not pulled the rug from under them, they might have filled that gaping hole and loved other women. But it was too late, and no one would ever know if Zaza and Sissy were rotten to the core, destined to become what they called “bitches” or “old bitches.” And so they resented them, almost, for being dead and for instigating that soul searching where you took the measure of your own ordinariness and pettiness, of the ease with which you were able to damn and judge others without first taking a good look at yourself in the mirror.

Fortunately September had arrived, because by the end of summer no fewer than half the members of the small community despised themselves enough to have to acknowledge it, while the other half, in taking stock of themselves, were learning to value the merits of mendacity. As for me, I was sheltered from the guilt gnawing away at the adults. I did not know the true meaning of the word “bitch,” nor the burden of sin contained in a simple thought, the awful temptation that can poison one’s mind as much as a done deed. If I avoided mirrors, it was not because of Sissy or Zara, but because I was twelve years old and I found myself ugly. But I revered those two girls with silky hair who smelled of peach and lily of the valley, who read photo-novels and danced rock’n’roll like the groupies who waggled their hips on TV to songs translated by the Excentriques or César et les Romains. To me they represented a quintessence of femininity to which I hardly dared aspire, a magazine femininity reserved for girls who had long legs and lacquered nails. I observed them from afar, and tried to mimic their moves and their poses, their way of holding a cigarette, all the time dreaming of the day I would exhale into the air around me the smoke from a Pall Mall the way Zaza Mulligan did, tilting my head back and making an “o” of my lips out in the midday sun. I picked up a wisp of straw and held it delicately between my index and middle fingers, saying foc, Sissy, disse boy iz a frog, until the cry of a loon or the hammering of a woodpecker brought me back home to the lake, the river, and the trees.

I dreamed of also having a friend, to whom I could say foc while swinging my hips, but the only adolescent my age at Bondrée was a girl from Concord, Massachusetts, who took herself for Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind, and who spent her days fanning herself on her parents’ porch. Taratata! In any case, I could only manage a few words of English in those days, see you soon, racoon, and other such fooleries, and I was sure that Jane Mary Brown, that was the girl’s name, couldn’t even translate “yes” or “no” into French. Franky, I not gave a down, I’d retorted the day she shut the door in my face, cheerfully butchering Clark Gable’s famous comeback to Vivien Leigh in the dimming light of a Virginia in flames. “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.” Jane Mary Brown had been dealt with.

Françoise Lamar, whose parents had bought the cottage next to us the year before, spoke for her part an English as impeccable as her French, despite a first name that drove her crazy every time an anglophone tried to pronounce it. It was her mother, Suzanne Langlois, who’d insisted that her daughter have a suitably French name, even if Franky was born of an anglophone father right in the heart of New Hampshire. At the beginning of summer 1967 she’d risen from the chaise longue where she baked herself from morning to night, to cozy up to Sissy and Zara, and she’d begun to smoke Pall Malls she concealed under the elastic of her Bermuda or polka dot shorts when she left the family cottage, slamming the screen door. I don’t know how she managed it, but it only took her a few days to be accepted by the Sissy-Zaza duo, which I’d thought was impregnable. From that point on there were no longer two pairs of legs stretched out on the rail of the Mulligans’ motorboat, but three, wrapped in a cloud of white smoke, as the radio blared out the hits of the day.

So began, long after the tale of Pierre Landry, the story of the summer of ’67 and Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, starting with that friendship and the three pairs of legs you saw everywhere, that you saw too much of, that were omnipresent, with the dirty jokes and guffaws that followed in their wake, dropping with the Kleenex into the open drains.

For the merchants of Jackman and Moose River, to whom he sold his pelts, Pierre Landry soon became Peter or Pete Laundry, a wild man jabbering a rudimentary “franglais,” and scenting himself with beaver oil. And that’s what he was, a wild man, an exile, but one who had not yet severed all ties with his fellows. Near Moose Trap he sometimes received visits from a hunter in October, a fisherman in June, with whom he shared a forty-ounce Canadian Club, but he spent the winters on his own, taking pleasure in the frozen beauty of Boundary, which, with his Canuck accent, he’d rebaptised Bondrée, the rough country of Bondrée. Among his more loyal visitors there was a young man who went by the name of Little Hawk, a rangy type with a nose like an eagle’s beak, to whom Landry had taught the rudiments of trapping, which he himself had learned from his father and grandfather, both of whom had lived off what the Beauce had to offer in furred and feathered creatures. Little Hawk was his friend, the only man he allowed to tend his traps, the only human being, in fact, with whom he was prepared to share the reality of death. He and Little Hawk didn’t talk the same language, except for a few words, but they shared a language all the same, that of the gestures and silences survival demands. When Little Hawk stayed for the night they sat on Pete’s shaky deck and listened to the forest, the growling and squealing of animals devouring each other. It was from the way Little Hawk then inclined his head that Pete had seen that they were the same, two people acknowledging the sad necessity of what some called cruelty, but which was only an echo of the earth’s ancient breathing. Then one day Little Hawk stopped coming. Landry waited for him, and concluded by his absence that he’d fallen into the trap that he himself had avoided by leaving Québec, refusing to be thrown into a war about which he knew nothing, and where death for him had no meaning. Little Hawk hadn’t been so lucky. Like thousands of other young Yankees, he’d won Roosevelt’s lottery for a one-way trip to Europe, called up along with all those who were deemed fit to fight and who asked themselves no questions about their aptitude for dying or for rubbing shoulders with death.

With no one to talk to about the beauty of the forest and the wildlife procreating there, Landry walled himself off in silence. At first he still talked to the trees and animals, and addressed the limpidity of the lake. He also talked to himself, commenting on the weather, describing the storms, even telling himself some lame jokes, stories of fishermen tangled in their own lines, but speech bit by bit abandoned him. He thought in words, but they stayed inside him, melted into his thoughts, lost themselves in the shapes of things there was no more point in naming. If the idea survived, it no longer expressed itself in sounds. During the time when Little Hawk paid him visits and shared his speckled trout, he’d rediscovered the true meaning of speech in the nights punctuated by silence. Little Hawk was not talkative, but he’d revived in him the desire to say things about the sky, to utter the word “blue” or “cloud,” midnight blue or thunderclouds. Once Little Hawk left, the blue no longer had any reason for being, nor did the smiles he tried to muster in the little mirror over the mottled basin where he washed himself and his pots and pans.

Then the blue was suddenly back with the arrival of the picks and shovels, the throbbing engines putting up cabins and putting down a road, blue and all the colours of creation, what with the sudden appearance of Maggie Harrison running along the lake in her scarlet dresses, dancing beneath the moon, and setting the skies to reeling. If he’d had the power Landry would have sent packing those infernal machines that seemed to have no goal other than to destroy everything that belonged to him, the silence, the clear water, the ethereal flight of the loons, but Maggie Harrison’s long black hair soon muffled the constant din. He instantly fell in love with this woman whose skin was too pale, and in his imagination he rebaptised her Marie in a stream’s pure water. Right away he began to watch her, swimming out from shore, striding along the beach with her dog Sugar, Sugar Baby my love. Concealed behind trees, Landry saw her dance with the waves, and whispered Marie, Baby, my love. Softly he repeated the words that expressed his love, softly, not to startle her, my love, because Maggie Harrison, along with the colours of creation, had given him back the longing for rapturous words, Marie, sweet bird, Tanager of Bondrée.

The honeymoon lasted for a time, then other, brutal words silenced Pierre Landry’s love song, obscene words, bastard, savage, uttered by men who’d seen him step out of the woods to walk on the beach. Bastard, savage, when he’d only wanted to come near, when he was just trying to stroke the contours of what had restored to him the spoken word. He’d stretched out his arms and Marie had pushed him back, get away from me, just when he was going to touch her hands, her eyes, her red lips that said don’t, her glistening lips that gave onto a great black hole and cried don’t, go away, don’t touch me!

That same day Pierre Landry buried himself in the woods, and he was never again seen near Boundary Pond. It was Willy Preston, a trapper people called The Bear, who found him in his shack a few weeks later, probably dead about the time of the new moon, his corpse eaten away by flies and maggots. Near the shack lay the body of Sugar Baby, Sugar Baby my love, disappeared that morning, disembowelled by a trap. A little after sunset Preston was seen coming out of the woods, holding to his body Sugar Baby’s remains. Maggie Harrison’s lament was then heard tearing through the ethereal flight of the loons, its echo merging with their complaints and sending shivers down the spines of even hard-working men. After two or three nights the echo went silent on the slopes of Moose Trap, and Maggie Harrison left Bondrée, leaning her shadow on the stooped shoulder of her husband. Like Landry, they were never again seen in the region, neither him nor her, crying out the name of Sugar Baby.

Among all the people who visited Bondrée at the time, only Don and Martha Irving, along with the Tanguays, Jean-Louis, Flora, and old Pat, had known Pete Landry, as far as you could know a man who came out of the woods only to melt back into them. They’d seen him not there but in the bay later called Ménard Bay, grumbling as he demolished his shack in order to rebuild it farther on, where the shovels and machines would not reach. They’d also seen him at the mouth of Spider River, stark naked, scrawny, his hip bones forming a bowl for his hollow belly, washing his clothes in clear water, without any soap to dislodge the grime.

Some people had hounded Don and Martha Irving, urging them to relate whatever they knew about Landry, but Don just mumbled that it was no one’s business, none of your goddam business, while Martha blew smoke in their faces from her fortieth Player’s of the day.

The same thing for Pat Tanguay, who refused to talk about Landry out of respect for the dead, he said, his basket of dead fish in his arms, and because he hated the inevitable gossip born of what people said, whatever it might be. Flora, his daughter-in-law, however, enjoyed circulating stories about Landry. She’d one day paid him a visit at his shack, neighbours had to get to know each other after all. Met by Landry’s cold gaze she’d retreated as far as the door, where she’d torn her pink cotton dress, a few threads of which stayed behind, caught on the door frame. Flora Tanguay never missed an opportunity to talk about that expedition, describing the beaver skins hanging on Landry’s walls like so many cadavers staring at you with their milky eyes. She invested the cadavers with the heads of lynx or wolves, and talked of blood, excess, and bestiality. She was the source for the story of Tanager, which she embroidered every which way, and altered according to her listener’s degree of captivation.

Several people claimed that Flora Tanguay ought to have been gagged for running off at the mouth and further sullying the good name of a man who, as far as was known, had never done any harm to anyone, not to Maggie Harrison or Sugar Baby, whose death was no more than a deplorable accident. Landry was just another of the forest’s victims, lost in his fascination for the beauty of flowers and birds. There was just one point on which everyone agreed with Flora Tanguay, and that was Landry’s feral behaviour, which got worse during the freeze-ups of his last winter, and brought disarray and disorder the following summer.

Still, no one thought after Landry’s death that anyone around the lake would turn deviant just from consorting with animals. The few oddballs still on the loose in the area were not really dangerous. There was old broken down Pat Tanguay, of course, who spent all his life in his rowboat, most likely to spare himself the endless prattling of his daughter-in-law, who could herself qualify as one of the local eccentrics. There was also Bill Cochrane, a veteran who heard the roaring of war engines on stormy nights, and Charlotte Morgan, who walked around in her pyjamas all day long, and, to preserve her white skin, only went out at dusk. But there was no one with an affliction similar to that of Landry, who’d ended up at one with the forest. As for Zaza Mulligan and Sissy Morgan, they were just different. Yet it was through them that the savagery had returned, because of them, they thought, without daring to say it out loud, because those girls were dead, good God, dead, for Christ’s sake! It was thanks to their beauty and Maggie Harrison’s, and to that of all happy and desirable women, that Pete Landry’s traps had emerged from the dark earth, and with them the violence of other men.

ZAZA

Who’s there? Who’s fucking there? Zaza Mulligan cried, before a man’s shadow, enormous to her eyes, crossed the path, its back bent. For a moment she felt the coolness of the ground numb her legs, like a long wet animal rubbing against her skin, and she sought support nearby, a tree to hold on to. This was not the time to faint, not now, Zaz, not now, please. She dug her nails into an oak’s bark, took a deep breath, and again cried who’s there? Who’s fucking there? trying to keep her cool, so the man wouldn’t sense the fear oozing from her every pore, but her voice was already cracking and tears were burning her eyes, tears she wiped away with the back of her hand, to restore to the dark and eddying night some semblance of brightness.

Who are you, for Christ’s sake? And the shadow remained silent, mute and motionless. All that reached Zaza was the sound of her own breath, which she tried to connect with that of the fox that had burst out in front of her a while ago, wind on my knees, fox in the trees. This kind of thing couldn’t happen to her, not to her, not now. It’s a fox, Zaz, you’re drunk, it’s a fucking fox, or a bear, that’s it, a damned bear, because Zaza would have much preferred to face a bear than this unseen and silent man. Talk to me, please! You’re not funny!

Warding off the images flashing through her mind, one more frightening than the next, she clung to the idea that someone just wanted to give her a good scare, that’s it, a bloody scare. Mark, is that you? Sissy? Frenchie? But the shadow stayed mute, shrouded in its own slow breathing.

Keeping her eyes on the dark, hushed stillness where the animal’s shadow had slunk away, it’s a fox, it’s just a bear, Zaza Mulligan began to retreat, silently, one step following on another, over the spongy soil. It’s a fox. Then a hand came down on her shoulder and Zaza Mulligan screamed.