Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

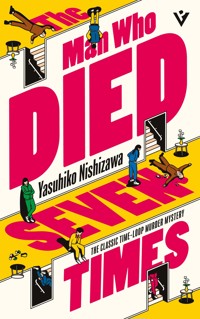

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

'Murder and time travel collide' Publishers Weekly In the middle of the family New Year's gathering at his home, Grandfather Fuchigami is murdered. But not for the last time. For his grandson, Hisataro, has fallen into a mysterious time-loop, in which he must relive the same day again and again. Every morning after his grandfather's death, Hisataro wakes up with a chance to find the culprit and prevent the murder. But day after day he fails, despite stumbling across clues aplenty in the shape of secret plots, illicit love affairs and jealous rivalries. With an extremely large inheritance up for grabs, everyone is a suspect - and Hisataro is beginning to wish he could leave this day behind...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 395

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

34

Contents

Character Tree

1

A First Glimpse of the Murder

We found Grandfather lying in the attic. It was a small, six-mat room, dark even during the daytime, its only window about the size of a piece of A4 paper. In the middle of the room, under the naked light bulb that dangled from the ceiling, was the futon mattress I’d left out that morning.

My grandfather, Reijiro Fuchigami, was sprawled face down on the futon. His left arm was trapped under his belly; his right hand grasped at the tatami mat. Just beyond his reach lay a large sake bottle. It must have been almost empty even before it fell over, because the spilt contents formed only a small dark patch on the tatami.

The few white hairs Grandfather had left, a sort of candyfloss-like swirl at the back of his head, were spattered a dark red. Lying in front of his face, hiding it from view, was a copper vase. Its former contents, a bunch of out-of-season moth orchids, were strewn across the tatami. Emi had bought them as a present for Aunt Kotono, knowing she liked orchids. So, really, they should have been in Aunt Kotono’s room. Not here.

He’s been hit with the vase. That was the thought that crossed my mind, and presumably everyone else’s. But no one—not 10Mother, not Fujitaka, not Yoshio, not Aunt Kotono, not Kiyoko, not Aunt Haruna, not Mai, not Runa—moved an inch. Even Ryuichi and Emi seemed to have frozen in the face of this momentous event. Everyone just stood there, jostling around the cramped doorway, barely able to breathe.

Eventually, after who knows how long, I found myself stepping forward into the room. This was my bedroom whenever we stayed at the mansion—a fact that seemed to have instilled a strange sense of duty in me. In any case, no one stopped me as I went to kneel at my grandfather’s side.

I took his wrist. It felt like a cut of ham that had been left out too long. There was no pulse. So he was dead. That much had been obvious from the moment we saw him lying there, but the confirmation still came as a shock. Or rather, it filled me with a fresh sense of despair.

I turned to look at my family, who were still peering through the doorway. I had no idea what you were supposed to do or say at a time like this. I must have had a pretty idiotic look on my face, but nobody was laughing. Instead their expressions were blank, as though all the emotion had been scoured from them. Watching them, I began to feel like bursting into hysterical laughter. For one thing, with the exception of Kiyoko, they were all clad in the bizarre combination of brightly coloured tracksuit and sleeveless chanchanko jacket that was the standard ‘uniform’ whenever we stayed at my grandfather’s mansion. Given the circumstances, there was something almost grotesquely hilarious about the mismatched outfits.

It was Emi who recovered first. She seemed to have received the silent message I was trying to convey, because she abruptly 11turned and clattered off down the stairs—presumably to phone the police.

Her departure broke the spell. There was a sort of collective sigh. Then, as if this was the cue they’d been waiting for, my mother, Aunt Kotono and Aunt Haruna suddenly turned on the histrionics. Father, Father! Oh no! How could this happen! That sort of thing. Sobbing and wailing as if trying to make up for all the time they’d been dumbstruck.

‘You mustn’t touch him!’ exclaimed Yoshio, restraining Mother as she tried to embrace my grandfather’s body.

‘We have to preserve the crime scene until the police get here!’ shouted Runa at her own mother, who was trying to do the same.

‘What crime scene? What are you talking about?’

I couldn’t even tell who shrieked these words—my mother or Aunt Haruna. In the close confines of the attic, all hell was breaking loose.

‘Isn’t it obvious?’ said Yoshio urgently. ‘Look at him. Just look at him! He’s been murdered!’

Murdered. That one word from Yoshio was enough to make everyone freeze again. Murdered, their fearful eyes said. Murdered, really? But how… how could something like this happen to us, of all families? This can’t be real. A murder, among upstanding citizens like us…?

But I was shocked for a different reason. The question on my mind was the same—how could this have happened?—but in my case it wasn’t just rhetorical. I really wanted to know how.

On this day, the 2nd of January, no murder was supposed to take place at the Fuchigami household. Its non-occurrence was something I’d already established as fact. Yesterday—or 12more precisely, on the ‘first’ 2nd of January—nothing untoward had happened. The day had ended without incident. And yet today—or rather, on this second version of the same day—my grandfather had been murdered. Why?

As these thoughts swirled through my head, my eyes briefly met Runa’s. She didn’t seem to register my gaze. She was too busy staring fearfully back down at Grandfather’s body.

Even at a time like this, I couldn’t help noticing that she wasn’t wearing her earrings. When had she taken them off? Yesterday—the real yesterday, that is, the 1st of January—I was sure she’d been wearing them. Like everyone else, she’d been obliged to change into the ‘uniform’ when she arrived at the mansion for our New Year’s gathering. Worn with her bright yellow tracksuit and blue chanchanko jacket, Runa’s earrings always looked utterly out of place—and yet she made it a rule never to take them off. Which, of course, only made their absence all the more noticeable…

2

The Protagonist Fills Us In

It was in the early years of elementary school that I first became aware of my ‘condition’. Not that it started then. My memories are a little vague, but I have a feeling I was born with it. It just took me a while to notice.

My name is Hisataro Oba, but not many people actually call me that. ‘Hisataro’ is a fancy way of reading the characters, and most people opt for the simpler ‘Kyutaro’ instead, which they combine with my last name to get ‘Obakyu’. Which is fun. ‘Obakyu’ also happens to be the name of a character from a manga series that was popular in the sixties, one my generation has barely heard of, which means the older folks get to have a good chuckle at my expense, too. In any case, I wish people would leave my poor name alone.

I’m sixteen now, and I attend the Kaisei Academy, a combined middle and high school in the city of Atsuki. I’m in my first year of high school. It’s one of the more prestigious schools in the prefecture, with a good track record of getting its pupils into top universities, and if you walk around with your Kaisei uniform on, the adults tend to treat you with respect. I attended a local middle school until last year when, 14in accordance with my mother’s wishes—maybe ‘orders’ would be closer to the mark—I took and passed the entrance exam and transferred to Kaisei for the high school portion of my education. When I reveal this to most people, they tell me, with obvious admiration, that I must have a good head on my shoulders, but actually that’s pretty far from the truth. In fact, it would be more accurate to say that I have quite a bad head on my shoulders. Proof of this can be found in the fact that, when it comes to my grades, I consistently rank among the lowest-performing pupils in my year.

You often hear about kids who manage to get into elite schools and then, through a sort of recoil effect, start slacking off and underperforming. That’s not what happened with me. The truth is, I’ve never been very academically gifted. And if you’re wondering how I managed to pass the entrance exam for a school as exclusive as the Kaisei Academy, well, that’s where my ‘condition’ comes in.

When asked to describe me, there’s a phrase people love to fall back on. Old for his years. Apparently, talking to me feels like sitting opposite some elderly man sipping green tea on the veranda and telling yarns about the old days while he soaks up the sun. This can only be described as an accurate assessment of the situation, the reason being that, despite my tender biological age of sixteen, my mind is at least thirty years old. Just to clarify, this is not a figure of speech. It’s a mathematically provable fact.

It was food that first made me aware of my condition. As a young child, the only thing I showed much interest in was filling my belly. And even at that age, I’d found the occasional lack of variety in the menu a little odd. 15

‘Tamagoyaki and potato salad, again?’ I’d muttered one day.

‘What are you on about?’ my mother had snapped. ‘We had hamburger steaks yesterday.’

At the time, I could only remember us having hamburger steaks a few days ago. I thought this was strange, but there was eating to be done, so I gobbled down the meal—only for the tamagoyaki and potato salad to appear again the next day. You can see why I might mutter ‘again?’ again. And when I did, my mother narrowed her eyes again.

‘What are you on about? We had hamburger steaks yesterday.’

At this point, even an elementary school kid with nothing but food on his brain started to notice that the problem wasn’t limited to the dishes on the table. When I turned my attention to the conversation around the dinner table, it turned out my father and brothers were talking about the same thing as the day before. Something about how Westerners were obsessed with picking on other countries for what they ate, and what difference did it make if we ate a bit of whale or tuna every now and then? Now, maybe I only noticed because the topic involved food, but they talked about the same thing the day after that, and the day after, too. The exact same exchange. The weirdest thing was that they were even repeating themselves word for word.

Then I realized that it wasn’t just my family. My teachers and friends at school were all saying and doing the same things as the day before.

‘Alright, everyone, listen up,’ said our square-faced teacher, eyeing us sternly through her black-rimmed spectacles. ‘No going near the shrine on the hill behind the school, okay?’

‘Why’s that, Miss?’ asked Oda, who at the time was my rival 16for biggest-dunce-in-the-class. ‘Is it haunted or something?’ he added quizzically.

‘How very unenlightened of you, Oda.’

‘What’s an “onion light” mean?’

‘It means you’re a very silly boy. No, there’s something much worse than your average ghost at the shrine.’

‘What, like a monster?’

‘There’s no such thing as monsters, Oda. You’ve been watching too much anime. No, some naughty kids have been going there and doing very naughty things. So, no going to the shrine on the hill. Otherwise you might see something you shouldn’t.’

‘What kind of naughty things?’

‘Well, that’s… erm… I… See, there was a girl from another school who went there to play, and she saw two older kids playing a funny game. The girl had taken her trousers off, and she was trying to make the boy do the same.’

‘Why did she try to make him take his trousers off?’

‘Well, it was all part of the game. I’m sure I don’t have to tell you what happened next.’

‘They swapped trousers?’

Just to be clear, Oda wasn’t trying to crack a joke. He was asking because he really didn’t know. In fact, I’d say that fewer than half the pupils in the class were precocious enough to decipher the teacher’s cryptic allusion. Even I had assumed they were just swapping trousers, as ridiculous as that seems now. Anyway, I digress, but the point is that this conversation was repeated verbatim in class the next morning.

‘Alright, everyone, listen up,’ said the teacher, her nostrils flaring like those of some beast scrambling after its 17prey—exactly as they had the day before. ‘No going near the shrine on the hill behind the school, okay?’

‘Why’s that, Miss?’ Oda’s voice sounded just as dopey as it had yesterday, too. ‘Is it haunted or something?’

‘How very unenlightened of you, Oda.’

‘What’s an “onion light” mean?’

‘It means you’re a very silly boy. No, there’s something much worse than your average ghost at the shrine.’

‘What, like a monster?’

‘There’s no such thing as monsters, Oda. You’ve been watching too much anime. No, some naughty kids have been going there and doing very naughty things. So, no going to the shrine on the hill. Otherwise you might see something you shouldn’t.’

‘What kind of very naughty things?’

‘Well, that’s… erm… I… See, there was a girl from another school who went there to play, and she saw two older kids playing a funny game. The girl had taken her trousers off, and she was trying to make the boy do the same.’

‘Why did she try to make him take his trousers off?’

‘Well, it was all part of the game. I’m sure I don’t have to tell you what happened next.’

‘They swapped trousers?’

This exchange happened in first period the next day, and the day after that, too—always starting with the teacher telling us not to go to the shrine on the hill and ending with Oda’s line about swapping trousers. And this wasn’t the only thing that kept recurring. In fact, everything that had happened the previous day—from the menu at breakfast to our teacher’s every word; from the specific details of the break-time dodgeball match to who got in a fight with whom, and who 18started crying, and who stepped in dog poo on the way home; from the menu at dinner to the programmes on TV—it was all exactly the same, day after day.

And then all of a sudden the repetition stopped, and the real ‘tomorrow’ arrived. No more tamagoyaki and potato salad for dinner, no more angry criticism of the views of Westerners on whale and tuna, and no more mention of trouser-swapping, except as something funny that the idiotic Oda had said the previous day.

As you’ve probably worked out, the same day was repeating itself over and over. Not only this, but I appeared to be the only one aware of what was happening. Like so many wind-up toys, everyone else would go around doing and saying exactly the same things as the day before—as though it were the most natural thing in the world and this was simply an ordinary day like any other. They had no idea they were acting out the same scenes over and over, like on a videotape caught in a loop. I was the only one who knew.

My secret name for this phenomenon is the Trap. Basically, once I fall into the Trap, I’m condemned to repeat the same day over and over until I climb back out of it. Like a scratched record where the needle keeps skipping back and playing the same passage over and over.

I never know when the Trap is going to spring into action next. As far as I can tell, there’s no fixed pattern for how often it occurs. It might be as often as a dozen times in one month, or only once in eight weeks.

But when it comes to the duration of each ‘loop’, and the total period for which I’m stuck in the Trap, there are clear rules. Each loop lasts one full day, from midnight to 19midnight—twenty-four hours, in other words. And the Trap always lasts for a total of nine days. Of course, that’s just my subjective experience of the situation, and in reality only one day has gone by—so strictly speaking, it would be more correct to say the day lasts for nine loops. It can also get confusing to refer mentally to ‘yesterday’ or ‘tomorrow’ while I’m in the Trap, so instead I tend to think in terms of the ‘first loop’, ‘second loop’ and so on.

As a general rule, once I’m in the Trap, everybody else’s words and actions are identical from one loop to the next. I say ‘as a general rule’ because they can also be deliberately made to do something else entirely. Of course, the person making them do so is none other than yours truly.

Once the Trap is activated, the only person who can intentionally follow a different course of action to the previous loop is me, because I’m the only one aware that time is caught in a loop. If I speak differently to someone from one loop to the next, they can’t help but respond differently. If I don’t complain that we’re having tamagoyaki and potato salad again, the end result will be that Mother won’t have said her usual annoying line about how we had hamburger steaks the day before. This ability to alter the ‘end result’ is where my ‘condition’ really comes into its own. In other words, I can deliberately alter the course of reality.

The benefits of this first became clear to me one evening when I was watching a baseball game with my father and brothers. It was the Yomiuri Giants versus their biggest rivals, the Hanshin Tigers, and the Giants ended up winning by a devastating margin. The match had been billed as a pitcher’s duel, but in the bottom of the fifth inning the Giants managed 20to score an astonishing and record-breaking nine consecutive home runs, from the leadoff hitter right through to the pitcher batting ninth, after which they just had to hold on for the win. My father, a Giants fan, was wild with joy; Yoshio, who hated their guts, was writhing around on the floor in agony; Fujitaka, who supported the Lotte Marines, sat there trimming his nose hair and yawning. It was a pretty lively evening.

Seeing as I didn’t have a team myself, I just sat there scratching my head and went to bed as usual. But when I woke up the next morning, I discovered that this dramatic day had fallen into the Trap.

Just like in the previous loop, the baseball game started. My father sat there excitedly with his beer and edamame. Despite still being in middle school at the time, Yoshio swiped a mouthful of his beer. Fujitaka was cleaning his ears with a cotton bud. In other words, everyone was having a fun enough evening in front of the television, except me—I was bored stiff. How could I not be? I already knew the result. Nine-zero to the Giants, a runaway victory. With the added bonus of a record-breaking nine consecutive home runs.

Before I knew it, I had blurted it out.

‘The Giants have got this one sewn up.’

My father loved the enthusiasm. Yoshio was infuriated.

‘What are you on about?’ he said. ‘The game’s barely started.’

Then it got started, and the score was nine-zero. The mixture of elation and despair in the living room was roughly the same as in the previous loop, except this time Fujitaka just yawned, without trimming his nose hair. My comment had subtly altered reality.

In the next loop, I got a little mischievous. 21

‘Hey, you know what?’ I said as my father and brothers were getting ready to watch the game. ‘I feel like something crazy’s going to happen in the fifth.’ They had a good laugh at my expense, telling me to quit the Nostradamus act, but it played out just as I’d predicted.

Still, they didn’t seem that blown away. I decided to take things up a notch. In the next loop, I very clearly predicted that in the second half of the fifth inning the Giants would knock out a series of home runs. When they went ahead and scored their nine homers, Father was too busy whooping with joy to notice how right I’d been, but Yoshio sat there staring slightly suspiciously at me. Fujitaka must have been slightly taken aback, too, because this time he failed to trim his nose hair or yawn.

In the next loop I got a little cocky and announced that I’d cast a spell on the Giants so that every single one of them would hit a home run. This was greeted with jeers of derision, but then the fifth inning came around and they all went quiet. There was something subdued about even Father’s celebrations this time, while my brothers were just staring at me like I was some kind of freak. That I found a little nerve-wracking.

Realizing I’d taken things a bit too far, I spent the sixth, seventh and eighth loops simply watching the game in silence. Then, in the ninth loop, I suggested to my father that we make a bet. If the Giants managed the win with a shutout, he’d give me some extra pocket money that week. Then Yoshio, apparently feeling I needed to aim a little higher, made the following generous and somewhat rash remark.

‘Idiot. If they manage a shutout, you can have every single one of my manga.’ 22

The result, of course, was that I found myself with a cash windfall and Yoshio’s entire manga collection. Now, if this was still the third loop, say, or the fifth, reality would have reverted to its original state and I would have had to do the whole thing all over again if I wanted to score the pocket money and manga, but because this was the ninth loop, this became the ‘definitive version’ of the day’s events.

Basically, there are always nine loops in the Trap, and the first loop is the ‘original’ version of the day in question. After that comes the second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth and final loop. Whatever I do in the second to eighth loops, reality always reverts to its original state, but whatever happens in the final loop becomes, for everyone else, the only version—and for me, the ‘definitive version’—of the events of the day in question.

Of course, my actions during the final loop may cause the day’s events to differ significantly from their original version. On the other hand, if I so choose, I can ensure that the final or definitive loop matches the original completely. This is what I mean when I talk about deliberately altering the course of reality.

By now you’ve probably worked out how I was able to pass the entrance exams for a school as exclusive as the Kaisei Academy. That’s right. If there’s one area where the Trap really shines, it’s school tests. And, in a complete stroke of luck, the Trap happened to activate on the day of the entrance exam. All I had to do was take the exam once, learn what questions came up, then memorize the answers afterwards. I got a total of eight chances to practise, too. There was no way I was failing that test. 23

A little unnecessarily, I scored full marks in every subject. This was partly to err on the side of caution, since I didn’t know the exact pass mark, but mainly just because I wanted to show off. My results caused a bit of a stir. The Kaisei entrance exam was famed for being one of the hardest in the country. No wonder people seemed to think my results heralded the arrival of a genius the likes of which the school had never seen—and might never see again.

But remember: the Trap is a ‘condition’ I’m subject to, not an ‘ability’ I possess. If it was an ‘ability’, I’d be able to enter the Trap whenever I felt like it. And if I wanted to really become a renowned genius, I could have made that happen. But it’s a ‘condition’, and I never know when it’ll affect me next. I can’t just decide to enter the Trap whenever we have our end-of-term tests, and even if I get lucky and the Trap happens to align with one of them, the tests are usually spread over several days.

As a result, my reputation at the school has taken a nosedive: I’ve gone from ‘greatest genius ever seen’ to ‘complete blockhead’. The disparity between my entrance exam results and those in my first end-of-term tests was so severe that it was even suggested I’d engaged in some sort of foul play. The school carried out a witch hunt among the teachers on the assumption that one of them must have leaked the question paper. Now that I think about it, the whole ruse was pretty thoughtless of me.

It wasn’t just the entrance exam. All the way through elementary and middle school, my results kept lurching between two extremes: exceedingly impressive and embarrassingly awful. Needless to say, the former I owed to the Trap. My report cards 24often featured comments like: Has ability, but effort seems to vary—Should aim for greater consistency.

The benefits of the Trap aren’t limited to tests, either. As I explained, with loops number two to eight, it doesn’t matter what I do during the course of the day: everything goes back to how it was the following morning. It’s a bit like hitting the ‘reset’ button on a video game: basically, I can do whatever I like. So, for example, when there was a girl in my class I was sort of into, I decided I’d ‘interview’ her over and over again. Over the course of eight loops, I asked her anything and everything. I found out her date of birth, who was in her family, her interests, even the story of the first time she fell in love. Then, in the last loop, I offered to give her a psychic reading. Girls love that kind of thing—so when I could apparently see into the depths of her soul, she was completely bowled over. Sure, I was only telling her things I’d asked in advance, but because of the ‘reset’, she didn’t remember a thing.

In my middle-school years, I used this trick to win the affection of quite a few different girls. Over time, though, it all got a little depressing. The main problem was that these dalliances never lasted. It was all well and good getting a girl’s attention with my ‘psychic’ routine, but afterwards they tended to lose interest pretty quickly. I don’t blame them, either. Even when a girl went out of her way to try to develop feelings, she’d soon realize that the object of them—me, in other words—had precious little to offer after the initial excitement.

It was the same with tests. When I aced an end-of-term test because it happened to coincide with the Trap, it wasn’t like I owed the result to my own ability. It was cheating, really—a sort of fraud. The result was that I could score a hundred per 25cent and still only feel the shallowest kind of satisfaction. At first I’d thought of my ‘condition’ as a source of amusement, but over time I began to realize that the truth was more depressing.

Still, even now, I never hesitate to exploit my condition when the situation requires it—as demonstrated by my stunning performance in the Kaisei entrance exam. I’d been expecting to fail the test, thus ensuring my mother’s transformation into one of those terrifying demons you see in a Noh play, so when the Trap happened to activate on the day in question, I was delirious with joy. It’s all pretty pathetic, really.

All this probably explains why people are always telling me I seem old for my years, or teasing me by calling me ‘Gramps’. I approach life with a sort of philosophical resignation, as though I’m convinced that in the long run, nothing really means anything. At the same time, it’s not like I have the drive to try to get by without the Trap. I’m sort of stuck, really.

On top of all that, as I mentioned, the Trap can sometimes happen upwards of ten times in a single month. If I had to guess, I’d say the average is around three or four times. In each Trap, I go through eight loops before I get to the ‘definitive version’ of the day. In other words, on a subjective level, I experience eight whole days that no one else does. Add up all that extra time, and a month lasts about twice as long for me as it does for everyone else. In other words, my mind experiences about twice as much time as my body. By now you’ll have realized why those comments about me having a mental age in the thirties weren’t just rhetorical.

The truth is that if I don’t have some fun with the Trap, then it’s basically just a torture device. Repeating the same day eight times can get pretty mind-numbing. It doesn’t really matter 26whether the events of the day in question are pleasant or not; the torture lies in the repetition itself. Which is why, rather than simply repeating the events of the original loop, I tend to tinker with them slightly in the second loop. And rather than simply repeating myself in the second loop, I do some more tinkering in the third. And the fourth, and so on. Then it all gets very depressing, so that in the final loop I often end up doing exactly what I did in the original loop and making that the definitive version of the day. And every time that happens, I feel a strange mix of frustration and emptiness, and ask myself what on earth any of it means.

This is probably why people are always saying I have the aura of some jaded old man. It’s true that, if I had a choice, I’d probably just retire from life and spend my days sitting on my veranda and dozing, occasionally rousing myself to pick fleas from my cat. I mean, if my days are going to repeat themselves, I might as well spend them all doing the same thing.

But I’m still in my first year of high school. Retirement isn’t the done thing at my age. All I can do is bumble onwards, caught somewhere between resignation and pure apathy.

The one area in which the Trap seems like it might be a universal force for good is when it comes to preventing accidents. Provided, of course, that I happen to fall into a loop on the day of the accident in question. Earlier I mentioned someone stepping in dog poo on the way home from school. Well, that person was me, and my realization that I seemed to be stepping in it in the same place every day coincided with my realization that the food and conversation at dinner were also repeating themselves. But because at that point I hadn’t yet fully grasped the rules of the Trap—for example, how many 27loops it would take for the ‘real’ tomorrow to arrive, or the fact that the last loop would become the definitive version of the day—my brand-new trainers ended up stuck with the same yellowish and apparently indelible stain I’d inflicted on them originally.

These days, though, I have a pretty solid understanding of the rules. So, if I were to have some kind of serious accident and the Trap happened to activate on the same day, I’d be able to alter my destiny and save myself. If I get hit by a truck, all I have to do is stay away from wherever that happened on all the subsequent loops, and I’ll make it through the day in one piece. Of course, this doesn’t just apply to me—the same principle means I can save other people, too.

The thing is, I haven’t actually had many chances to take advantage of this aspect of the Trap so far. Since the dog-poo incident, my life hasn’t exactly been filled with drama. Neither have those of the people around me. It seems I’m just not destined to witness anything that exciting.

Of course, one glance at a newspaper is enough to confirm that plenty of accidents and crimes happen every day. There was a period where, whenever the newspaper on the day of the Trap revealed that some tragedy had occurred, I’d feel a sudden sense of duty. I’d tell myself that maybe the reason I’d been born with my ‘condition’ was that I had some divine calling to help those around me and make the world a better place.

But the world soon brought me down to size. To take just the example of traffic accidents, there would often be more than one of them reported in the newspaper, in which case I ran into the problem of which to prioritize. When they occurred 28at disparate locations within a short space of time, preventing all of them was physically impossible.

Still, if it meant I could save just one person, surely that was better than simply sitting around twiddling my thumbs. But the problem then became: how do I choose? At first I decided to focus on fatal accidents, but then it struck me that the ones where someone ended up in a coma were, in a sense, even more tragic. Once that sort of confusion had set in, I began losing all sense of what was right. It wasn’t just traffic accidents that featured in the newspaper, either. What about people getting lost at sea or in the mountains? Or burning to death in a fire? Gas explosions? Typhoons, earthquakes, other natural disasters? Murders, even? Some things seemed so far out of my control that it seemed ridiculous to even try.

In the end, after a great deal of agonized soul-searching, I simply gave up. There were limits to what I could achieve on my own. Instead, I decided to prevent only accidents that involved me or people I knew, or which I happened to witness directly.

In short, the Trap wasn’t quite the universal force for good I’d imagined it to be. It’d be more accurate to call it a force for my own good. Whenever I found myself gazing at a newspaper article on a Trap day, I’d remind myself of this and wait for the guilt of not saving lives to subside—drawing on whatever fatalism or agnosticism I could muster to convince myself that whatever happened in the world was always going to happen, and for reasons beyond human understanding. And so my ‘jaded old man’ persona became only more pronounced over time.

The conclusion my ‘condition’ has led me to is this: that our existence is predicated entirely on our own self-interest. 29I know that sounds like a very convenient excuse. But then of course it does—in fact, that very fact is compelling evidence for my claim. Much as it pains me, I have no choice but to declare that the only person I’m capable of saving, in the end, is myself. Maybe, at a push, my family and friends—but even then I’d still essentially be putting my own interests first.

By good fortune—if I can call it that—as I mentioned above, I don’t seem destined to witness many serious accidents, and in my sixteen years on this planet, neither I nor anyone I know has been involved in one personally. As a result, it would be fair to say I’ve never succeeded in making effective use of the Trap to achieve anything. Yes, I used it to get into my high school, but the drawbacks of that are beginning to look like they might outweigh the benefits.

Maybe my real mistake lay in thinking anything positive would ever come of this troublesome ‘condition’. Like I said, it’s not an ability, but just that: a condition. A disorder I have to live with for the rest of my life. There’s no reason why it should ever be remotely helpful to anyone.

Just live with it, and forget about trying to use it for good. That was my philosophy. Until, that is, the New Year’s holidays of my first year of high school.

3

The Characters Assemble

‘Happy New Year!’

Ryuichi Tsuchiya, my grandfather’s personal assistant and driver, bobbed his head at us, the friendly smile on his face seeming to hang in the air for a moment afterwards.

‘Happy New Year,’ said my mother, returning the greeting with a series of bows bordering on the obsequious, especially given that Ryuichi was about the same age as her sons. She seemed to bow a little deeper every time we visited my grandfather’s mansion for the New Year. ‘Thank you for everything you did last year, and all the best for the year ahead.’

‘To you, too. It’s been—’

‘Really, all the very best indeed. Ah, I almost forgot.’ Her voice dropped as she produced a decorative paper envelope and practically forced it into Ryuichi’s hands. Apparently she was giving him the otoshidama money usually bestowed on children at this time of year. ‘It’s not much, but I’d like you to have this.’

‘Oh, I can’t possibly—’ Ryuichi replied, even as his hands looked for somewhere to put the envelope. He appeared to be 31struggling with the fact that the clothes he was wearing had no pockets. ‘You really shouldn’t have…’

‘Really, it’s nothing at all. A trifle,’ she insisted, but I wouldn’t have been surprised if the amount of money she was handing him was far more than she ever gave her actual sons. ‘Now, where’s…?’

‘Ah. Mrs Kanagae?’ said Ryuichi, apparently grasping just from the way my mother was peering at the house that she was looking for her youngest sister. This sharpness, despite his young age, was probably why my grandfather had made him his right-hand man. ‘Already arrived. With the young ladies.’ He glanced surreptitiously at me and my two brothers, standing behind Mother. ‘By the way, your husband—is he…?’

‘Right. Yes. He’s, erm…’ Flustered, Mother began gesticulating wildly with her arms. One of them collided with Fujitaka, who was standing just behind her, though she didn’t even seem to notice him flinch in pain. ‘Yes, he, er… said he was feeling a little under the weather.’ She chuckled awkwardly. ‘Honestly, I don’t know what to do with him sometimes.’

‘Ah. So he’s… ill?’

‘Oh, I wouldn’t go that far. He’s fine. There’s barely anything wrong with him. Really. It’s probably just his age.’ She gave another forced-sounding chuckle.

‘What an unfortunate coincidence,’ said Ryuichi, wincing slightly at my mother’s shrill laughter. ‘Your sister’s husband is also unable to attend this year, as it happens.’

‘Really? Hitoshi’s not here, either?’ Mother gazed off into space for a moment, as if trying to quickly work out whether this was good or bad news, as far as she was concerned. ‘Why’s that? Is he unwell, too, or what?’ 32

‘Well, erm…’ began Ryuichi, but at this point Fujitaka suddenly broke in with a laugh.

‘I think I know why.’

Outraged by the fact that her son, who she seemed to view as her own property, would dare to hide even the slightest snippet of gossip from her, Mother narrowed her eyes fiercely at Fujitaka.

‘What, know something we don’t? Go on, then—out with it!’

‘How about going inside first of all, Madam?’ offered Ryuichi, who seemed anxious about the direction the conversation was taking. ‘The Chairman and President are waiting.’

‘Alright, then. But…’ Mother gave Ryuichi a fresh once-over with her eyes. He was clad in a loose-fitting black tracksuit, on top of which he wore a dark blue chanchanko jacket. It was a pretty amusing getup, all told—and also faintly absurd for someone to wear while politely greeting his boss’s family. ‘He won’t let us in unless we dress up like that, will he? It’s ridiculous… I mean, really… Is there no other way?’

‘I’m very sorry. I’m under strict instructions from the Chairman not to let anyone in until they’ve agreed to change clothes.’

‘My word. I mean, I know Father has his whims, but still…’ For all her complaining, Mother had still taken care to turn up in a casual outfit she could easily change out of. ‘Fine, then.’

‘Thank you. This way, please,’ said Ryuichi, gesturing towards the old house that stood apart from the main mansion. ‘Emi will see to you in there.’

‘Right, then, you three,’ said Mother, fixing me and my brothers with an imperious glare, as if to compensate for all 33the toadying she’d done to Ryuichi. ‘Hurry up and get changed. No dawdling, you hear!’

With these harsh words—as if our ‘dawdling’ was somehow to blame for all her problems—she disappeared into the old house. Meanwhile, Ryuichi led us into the annex that stood across the courtyard from the old house, and which served as the men’s changing room.

‘Sheesh,’ sighed Yoshio as he pulled on the yellow tracksuit that he found waiting for him. ‘The same lame outfits, year after year. Ryuichi, don’t you think we should be wearing something a little, I dunno, fancier for the New Year?’

‘You may have a point,’ said Ryuichi, apparently unsure if he should fully concur. He nodded vaguely. ‘For the gentlemen it’s one thing, but for the ladies…’

‘Exactly. I mean, we only meet up like this once a year. I’m sure they’d prefer to look a little more glamorous while they’re at it, right? Instead, just look at this…’ Yoshio gave a dramatic sigh as he pulled on his blue chanchanko. ‘I just don’t see why we have to sit around celebrating in clothes that, frankly, I’d be embarrassed to be seen nipping out to the convenience store in. I mean, I’m not some penniless student any more… And it means I don’t get to see Runa in a kimono…’

With that last comment, a strange tension seemed to suddenly fill the changing room. This was getting interesting. Runa was the second daughter of Aunt Haruna—in other words, our cousin. I’d long known that Yoshio was infatuated with her—he seemed unable to hide it—but the charged atmosphere in the room indicated that Fujitaka, without ever having expressed his feelings in so many words, was also not immune to her charms. It wasn’t just Fujitaka, either. Ryuichi, 34of all people, must also have fallen under her spell, because he’d joined Fujitaka in staring somewhat menacingly at Yoshio.

‘You’re lucky—at least your tracksuit’s yellow,’ I said, in an attempt to lighten the mood and avoid being embroiled in this bizarre standoff. ‘Mine’s red. A red tracksuit and a chanchanko. It’s so… decadent.’

My branch of the family—the Oba family, that is—had only started joining my grandfather, Reijiro Fuchigami, for his New Year’s celebrations a few years ago. Before that, we’d been estranged from him for various reasons. It wasn’t just the Oba family, either. The family into which his third daughter, Haruna, had married, the Kanagae family, had also distanced themselves from him completely. Like us, they had only begun attending these New Year’s gatherings in the past few years.

At this point I should probably explain a little about my grandfather and his company, the Edge Restaurant Group. Originally, Reijiro and his wife, Fukae, had run a small restaurant serving Western-style cuisine on the outskirts of the city of Atsuki. It seems he was quite the talented cook; at the same time, he was a pleasure-seeker with a weakness for the three cardinal sins of any husband—drinking, gambling and philandering. When it came to gambling, in particular, there was a period during which he would happily squander the restaurant’s entire monthly earnings in a single evening, causing my grandmother all sorts of grief.

They had three daughters. My mother, Kamiji, was the eldest. After that came Kotono, followed by Haruna. As children, all three of them resented their father for the hardship and poverty he brought on the family. However much he angrily insisted that they do so, they could hardly be expected to respect a 35father who couldn’t afford to buy them proper clothes and diverted the money that was supposed to pay for their food into his gambling. On top of that, he never missed an opportunity to demand that one of them marry a man who would be happy to be adopted into the family in order to carry on the Fuchigami name. In other words, they were expected not just to put up with years of hardship, but also to become the successors to a family which had nothing to offer them but a name and mountains of debt. Who could blame them for desperately wanting to escape a house like that—a father like that—as soon as they possibly could?

My mother, Kamiji, was a model daughter in one area only: her grades. Fending off her father’s spiteful insistence that high school was a waste of time and she’d be better off helping him at the restaurant, she graduated top of her class and received a scholarship to study at Atsuki National University.

The truth of the matter was that academic success was my mother’s only escape route. Running away from home would probably only have meant swapping one form of misery for another. If she wanted a decent job, or a husband she could depend on, first she needed to get herself to university: that seems to have been the thought that kept her going.

As if in support of this determination to escape, my grandmother died from a stroke just before my mother graduated. Once the funeral was out of the way, my mother never returned to the family home, instead marrying a man her age she’d met at university. That man was my father, Michiya Oba. My mother didn’t even invite her two younger sisters to the wedding, never mind her father. It was her way of showing that she intended to permanently sever all ties with the Fuchigami family. 36

Meanwhile, her sisters panicked. Not only had their mother—their ally, at least up to a point—died on them, but their older sister had run away, leaving them to handle the burden that was Reijiro on their own.