5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Story Hill Publishing

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

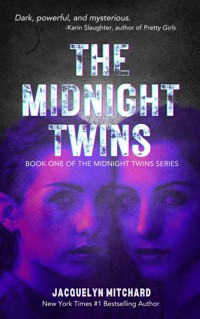

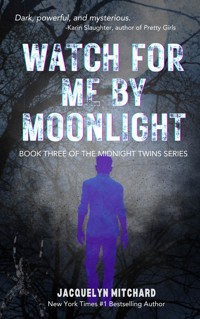

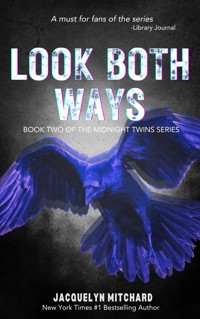

Psychic Twin Sisters Face Ominous Visions in Riveting Supernatural Tale

Mallory and Meredith Brynn seem like typical 13-year-old identical twins until they begin having vivid dreams and visions of ominous events in their small town. The sisters soon discover they have inherited an extraordinary psychic gift that runs in their family's female lineage - the ability to see into the past and future.

As the twins start coming to terms with their powers, their terrifying visions begin implicating people close to them in sinister acts. Mallory and Meredith find themselves on a dangerous quest to intervene in the fates they foresee and stop tragedy before it strikes.

Guided by their beloved grandmother, who helps them understand their gifts, the sisters navigate profound questions of destiny and sacrifice. Their bond is tested like never before as they shoulder the loneliness of being different and attempt to use their abilities for good.

This riveting supernatural tale follows the twins' poignant journey of self-discovery as they learn to cope with their blessings and curses. It explores the redemptive power of sisterhood in the face of unrelenting adversity.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Jacquelyn Mitchard

The Midnight Twins

Book One of the Midnight Twins

Title Page

The Midnight Twins

Jacquelyn Mitchard

Copyright

© 2018 Jacquelyn Mitchard

This book is licensed for personal use only. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes) prior written agreement must be obtained by contacting the author. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Publisher’s Note

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Dedication

For Kathy and Karen, and the single sentence that inspired this book,

and for their big sister, Deb.

Everything you say is funny or beautiful.

LOOK BOTH WAYS

Meredith and Mallory Brynn looked exactly the same.

So it was natural for people to expect them to be the same.

Of course, not all people who look the same really are.

Meredith and Mallory were identical twins. But they were opposites.

One person made into two by luck or by fate, until they were almost teenagers, they never, not once, thought of themselves as being two separate people. Identical twins often don’t. They knew each other as they would never know anyone else, before they understood even the fact that they were people, before they could talk, before they had names. Yet they acted differently from each other, spoke differently, thought differently, and wanted different things. They played with different toys, laughed at different jokes, excelled at different subjects in school. Their mother stopped dressing them alike when they were just two years old, because Mallory didn’t like dresses and pulled off all the buttons.

In their lives, being identical would be the easy part. Being different would bring them power, and power almost always comes paired with grief.

Most children love hearing the story of their birth, but the Brynn girls heard theirs so often that they got sick of it, even though it was, they had to admit, a pretty unusual story. Their mother, Campbell Brynn, a surgical nurse, went into labor at a New Year’s Eve party. She wasn’t due to have the babies for another three weeks. There was a mad dash to the hospital, where the girl’s father, Tim, and Bonnie Jellico, another nurse and Campbell’s best friend, held her hands while the babies came—with startling speed, quicker than anyone would have imagined for firstborn children. The doctor arrived with just moments to spare.

Meredith was older, born first at 11:59 p.m. Mallory came just two minutes later, at 12:01 a.m., the first baby of the New Year in the small town of Ridgeline, New York. With all the hands and machines and towels and instruments freewheeling around the delivery room (because when twins are born, there needs to be two of everything—two newborn specialists, two neonatal nurses, two warming beds), it took a while for someone to notice and exclaim, “They were born in different years! Identical twins, and they’ll never have the same birthday!”

Now, it wasn’t as though Campbell forced this story on people. It came up naturally. (One thing twins learn early is that, for the rest of their lives, people are going to ask, “Which one of you is older?”) Campbell would try to get away with saying that they were born on New Year’s Eve and leave it at that. Or she would try to tell the funny bits, about how furious she got at Tim for ignoring her and watching the shimmering ball above Times Square on TV, as well as admiring women in the crowd who were dressed up in copies of early-twentieth-century finery (since the movie everyone was watching that year was Titanic).

At the hospital, as the moment of the birth grew closer, Tim looked up at the TV and said, “We could go there someday. Don’t you think it would be fun? Think about next year and how beautiful you’d look in one of those low-cut dresses. Or we could go there when the twins are three. For the new millennium. Would you like that?”

And Campbell, her face as red and swollen as a cartoon chipmunk’s, said, “I would like it. I would like it even more if you fell off a cliff.”

She told the nurses that they had planned to name the girls Andrea and Arden. But moments after their birth, Tim heard Campbell say, “Hush, little Meredith. There, there, Mallory.” And barely had he opened his mouth to object when Campbell snapped, “I know what we planned. But when you give birth to two babies in two minutes, you can name them Batman and Robin if you want. Their names are Meredith and Mallory!”

Campbell never forgot to mention that, technically, the girls were born in different years. It made them unique—and if Campbell wanted anything, it was never to diminish the twins’ uniqueness. At least as far as their mother knew, they had little enough of that to begin with—certainly when they were small.

But even before they were born, the babies knew how it was to be completely bonded and completely opposite. Meredith was happy by basic nature. She would always love pretty things, pretty people, and hopeful solutions. Mallory was intense and would always worry, even when she didn’t need to. She would look at questions in complicated ways and refuse to accept the easy answer. Merry would attract friends the way Velcro picks up tennis balls, while Mallory, unless she was playing sports, would spend most of her time with her sister or else alone by choice. Before they came into the great world, she was the baby content to float in the warm dark seas, examining her fingertips and stroking her cheek, trying to figure out what being a person meant. Meredith wanted to feel and find everything. Side to side and up and down she zoomed, like a mermaid in flight. All that zooming got on Mallory’s nerves as months passed, and the quarters got closer in there. She sometimes put out a tiny hand to slow her sister down. And Meredith always responded. At Mallory’s touch she settled down and, entwined, head to foot, they would drift into sleep, as the voices from outside slipped into their dreams.

These voices were ones they grew to recognize, as they bloomed from pink buds to babies fully formed—with fingers and toes and personalities—separated only by a wall of muscle from the great world all around them. They heard the voice of their mother, giving and taking orders all day, a quick, light, practical note in a room where the beeping and whooshing and clanging were the music. There was their father—friendly and loud, but also protective and calm. There was the voice of their grandmother, a soft voice that always alerted the babies to listen closely, even before they were horn.

One day, the twins listened as Gwenny told her daughter-in-law that both babies were girls. Much as she loved her mother-in-law, Campbell was annoyed. Like any new mother—or at least most of them—she wanted the surprise. So her voice was sharper than she meant it to be when she asked just how her mother-in-law knew the babies’ gender and why she considered this so important. Yes, she knew that all the women in her husband’s family supposedly had “the sight.” But at least back then, Campbell thought that “the sight” was a bunch of baloney. And so Gwenny’s prediction was just a lucky guess. Campbell wiggled her foot with impatience. She wished that Gwenny would get on with it.

“Well, they’re both girls. So they’re probably identical twins. Identical twin girls run in our family,” Gwenny said. “I thought you should be ready. Twins are different from other babies. And not just because there are two of them. They’re joined. Not joined like kids who are born sharing a hip or a rib. Joined by the spirit.”

Campbell still didn’t get why this was such a big deal. She’d read up on identical twins, in several authoritative books from the library. What Gwenny seemed to want to tell her was something else, something more; but she didn’t say anything else, or anything more. Finally Campbell decided that Gwenny was being unnecessarily dramatic. Being dramatic seemed to run in her husband’s family, too. The baby twins sensed, however, not with words but with feelings, that what Gwenny said about their being inseparable was important.

And they were inseparable.

After they were born, for example, they fretted and sobbed in their sweet little cradles. Meredith couldn’t bear to be away from Mallory. Mallory was cranky and tense if she couldn’t see her twin.

Their mother finally decided to ignore the experts’ advice.

Weary to the ends of her fingers, she put them together in one cradle next to their parents’ big bed. From then on, she found them each morning, one right side up and one upside down, each clasping the other’s tiny foot. At precisely the same moments, throughout the night, they made precisely the same sounds—chirping and cooing—turning over at precisely the same time. They never woke up for feeding, though they drained Campbell during the day. She didn’t realize it, but she had given them what they wanted most of all. They needed nothing, not even food, more than they needed each other. In fact, on the night they were born, Meredith, as excitable and bouncy in the world as she had been before she arrived, wriggled and shuddered with angry, piercing cries the moment she slid with a smack into the doctor’s hands. The huge, cold new place was bad enough. Being alone—without her other—was even worse. The doctor was just glad that this baby was a live wire, because twins who came early could be tiny and in trouble. But the first baby girl grew calm as soon as her sister arrived, just two minutes later, quietly gazing around her and breathing slowly on her own. He couldn’t have known why. Without being able to speak aloud, Mallory and Meredith were already speaking to each other in what would become their private language. Mallory thought her way to Meredith. Soso, Mallory thought to her sobbing twin. Soso . . . don’t cry. Everything is all right. Meredith heard and quieted down. It would always be “soso,” a word that meant nothing to anyone but to them. Soso . . . don’t cry. Siow . . . I’m scared. I’m hurt.

Bonnie Jellico, who had never witnessed twins born in such a short time except through a surgery, remembered thinking it was like seeing two copies glide out of the portal of a copy machine. They were beautiful, with thick black hair and softly pointed chins.

But they weren’t copies.

When they looked at each other, they saw what other people see when they look into a mirror.

It would be years before anyone except their mother noticed that Meredith was right-handed, while Mallory held her spoon with her left hand. Merry’s straight, silky hair parted on the right, Mally’s on the left. The family also assumed that as they grew, they would have similar personalities but spend more time apart.

Instead, they had dissimilar personalities but refused to spend more time apart: Merry even came home from sleepovers before breakfast. That was only one of many things people assumed about them—and which, like the others, was wrong.

When they were three, Grandfather Arness, their mother’s father, built them matching youth beds. On one headboard they pasted all their cartoon and holiday stickers and made their first attempts to write their names in crayon. After they fell asleep each night, Campbell tried moving one of them back into the unused bed. Though she didn’t scream as though she were being dissected, the way she had when she was born, Merry couldn’t be at rest until she was with Mallory, or at least knew that Mallory was nearby and okay. Outgoing Merry, happiest surrounded by all kinds of people, dancing when she could have walked and jabbering before she thought about what to say, seemed to be the natural “leader.” In fact, Meredith always waited, especially on important matters, to see what Mallory would do or say. It was she who was the clingy one, who crept every night into Mally’s bed—until they grew so big that they literally had no room to turn over without kicking the other onto the floor.

But that took years, because neither of them got very big, ever.

Their mother listened to their language and tried to learn what the words meant.

“Soso,” they told each other—and Campbell translated this to mean “Everything is fine. Don’t cry.”

“Laybite,” they told each other when one twin needed the other to stop talking—right that very minute.

But even as closely as she studied them, their mother couldn’t quite believe how often they didn’t need words at all.

She never knew that when one looked at the sky, or sprained her ankle, the other saw the star or winced at the pain. When they grew older, if one wanted to kiss a boy, the other felt the longing, even if she didn’t like the boy.

As the years passed, and Campbell felt sure that the girls talked to each other with their minds, she didn’t tell anyone, not even Tim. Of course Tim knew, too, or thought he did, but he didn’t tell Campbell. Campbell didn’t want to upset Tim. Tim didn’t want Campbell to worry. He was used to twin ways. Both his mother and his grandmother were twins.

The night Mallory and Merry were born, Grandma Gwenny couldn’t even wait until morning to see them. Their grandfather assumed that Gwen had to go running out into the snow (wouldn’t catch him doing that!) because she was finally a grandmother. But the reason was bigger than that. Gwenny crept into the room and kissed her son, Tim, who was asleep in a big chair with a hat that read “Super Male” over his eyes. Then she tiptoed over to Campbell’s side, hoping not to wake her or the babies, hoping just for a glimpse.

But Campbell had just finished feeding the girls. She felt shriveled as a raisin but happy to see Gwenny’s eager face.

“Don’t you know how to celebrate New Year’s Eve!” said Gwenny, shaking her finger at Campbell.

“They’re pretty cute. And I’m pretty overwhelmed already,” Campbell said with a sigh. “Well, at least we’ve got our whole family, all in one night.”

“No, I think . . . well, I know that you’ll have a little boy,” Gwenny said.

Campbell wrinkled her nose. There went Gwenny with her visions again.

“And you’ll be glad because identical twins are . . . they’re one person. You remember what I said that time. They’ll be closer to each other than anyone else, even closer than they are to you.”

How awful, Campbell thought.

She tried to smile, but had to bite her lip to stop it from trembling. Exhausted, and having just met two people she already loved more than her own life, she didn’t want to hear that she would never be as dear to them as other mothers were to their daughters. But she listened—and took a moment to reflect on just why—because something about Gwenny seemed so sad and yearning underneath the happiness. Gwenny sat down on the windowsill and gazed out at the veil of snow. “Isn’t snow beautiful? But so treacherous, especially on a night like this with people-swerving around like fools. We’re probably the safest people in Ridgeline right here. But you can’t deny that there’s something magical about snow.”

A scattering of little thoughts coalesced into a tiny whirlwind in Campbell’s mind. Her mother-in-law wasn’t thinking only of snow, or of her new grandchildren. Gwenny, she remembered, had been an identical twin, whose sister had died as a child. No one talked about the accident. After that night, for the rest of her life, Campbell would be able to picture the grief on Gwenny’s beautiful unlined face in profile, by the light from the window. How painful it still was for Gwenny, after fifty years, to be without her . . . other. Other? Campbell thought. What did that mean?

The babies, nearly asleep, heard Campbell thinking and were happy that their mother was smart.

But there was more to Gwenny’s stew of emotions than even Campbell knew.

She had to confess that she nearly hoped that these little girls would be regular kids, unusual only because they were twins—not in the strange, painful, potent, almost unbearable way Gwenny knew so well. But she sensed that they were, and confirmed that for herself the first time she looked into their round, curious, river-colored eyes. As proud as she was of her heritage, as much as she knew that the gift was important—to her, and if God gave it, she supposed, important altogether—it was a two-hearted bequest, a blessing with a sharp bite. If only she could explain to them what life held for them, in a way that would spare them fear or pain. But she couldn’t. She didn’t know, for certain, what the nature of their gift would be. She could not have guessed its supremacy over all the twins in previous generations of the Brynn family. But she did know that the little girls would never put faith in what they needed to know unless they learned the old and cruel way—on their own.

Four and a half years later, Campbell sat on a bench next to the cold ashes of the fire pit, her arms wrapped tightly around her two-year-old son, Adam.

Police swarmed the woods and clearings surrounding the Brynn family’s cabin camp, some restraining great wolf like dogs on leather leashes.

She had not watched Meredith closely enough. Meredith was dreamy and creative and liked to wander. So long as she held hands mentally with Mallory, she thought she was safe. Someone said that Merry had followed a deer and twin fawns down the hiking path two hours earlier. The sun hadn’t quite set then, and now darkness was closing in. She was such a little girl, and these woods and hills so vast, the cliffs above the river so steep.

Campbell thought she would like to die that instant. She blamed herself.

Mallory sat nearby on the grass with her back to her mother, playing with a shell necklace. Tim’s aunt had given the girls the necklaces, identical except for the colors, earlier in the spring. Mallory’s lips were moving as she twirled the shells, but she made no sound that Campbell could hear. Unless she spoke to Meredith, Mallory wouldn’t say a thing, Campbell knew. Not for the second or third or fiftieth time, Campbell thought of Gwenny’s words on the night her daughters were born, about twins being one person. After a while, Campbell asked, softly, “Are you . . . talking to Merry?”

Mallory, absorbed, didn’t answer. Campbell asked again.

“Laybite,” she said softly. Campbell knew this meant, in twin code, something about the need to be quiet.

“Mallory?” Campbell asked again. “Are you talking to Merry?”

Briefly, but with an effort, Mallory answered, “Yes, Mommy.”

“Did you tell her to stand still and not be afraid of the big doggies?”

“Yes, Mommy.”

“Mally, do you know where she is? Is she afraid?”

“No, she’s not afraid,” Mally said. “I’m talking her, so she knows the doggies will come.” When Mally was upset, she slipped back into the kind of sentences she’d used when she was three. “By the water drops. Soso. Soso.”

“So what?” Campbell asked, forgetting a twin word she did know. “Are you sure you don’t mean down by the pond in the middle of the river?” Campbell asked, as she had half a dozen times before, her skin tightening with the fear she felt of the slippery, sucking mud on the riverbank. Meredith and Mallory could swim, but just, like puppies. “Is Merry at the river?”

“ No, Mommy,” Mallory said sharply, dragging her eyes up to meet Campbell’s. “I told you. The water drops. Not the swimming hole.”

“Rain?”

“Mommy!” Mallory snapped, suddenly angry. She had always been the more volatile, Merry the more . . . well, merry. Campbell felt a total fool, gingerly trying to avoid riling up a kindergarten child.

“Just stop you!” Mally cried out.

Campbell glanced around to see if Tim or his sisters and any of the cousins and their spouses, or his ancient aunties, had noticed Mallory’s outburst. Tim and his father and brothers, compelled by some ancient law of being men, were out following the police, probably messing up the dogs’ scent trails, Campbell thought in a moment of spite. The women remained behind, helplessly making and drinking gallons of coffee.

Campbell thought that the theory of relativity had never been better illustrated. Every minute was only sixty seconds long, but it stretched out like bubble gum until it sagged and tore and then it stretched again. Besides Campbell, only her mother-in-law, seated lightly on the arm of one of the big swings, never moved. She watched Campbell with an unwavering gaze of pity—though she did not venture closer. Campbell supposed that she was thinking about her own twin as well as her granddaughter.

Campbell didn’t want to know what her mother-in-law was thinking.

A half hour passed.

When Campbell glanced at her watch again, another three minutes had expired.

Suddenly then, Campbell heard the shouts from the woods: “We found her!” and “She’s fine! We’ve got her!”

She noticed, with a helpless sadness—how could poor Adam ever understand this?—she had actually gripped her little boy’s wrists so tightly, she had left red finger marks on his skin. Then she let herself take a full breath and began to cry for the first time since Meredith had disappeared.

A burly older officer carried Merry out of the woods and set her down. She ran toward Campbell’s open arms . . . and straight to Mally.

“Did you watch water?” Mally asked, reaching out to pull a burr from Meredith’s thick, shining, black bobbed hair that swung just above her shoulders. Mallory’s hair was short, swept back in a feathery cap.

“Beester!” Meredith said. “I watched so long!” Merry then reached up and patted Mallory’s face, as though she, Merry, were blind. To Campbell’s astonishment, Mallory began touching her sister’s elbows and wrists, then her knees, watching Merry’s face for a reaction. She was feeling for broken bones . . . she was making sure that Meredith was not hurt.

Out of breath from having jogged half a mile back on the pebbled trail down the ridge with his little bundle, the police officer finally caught up and said, “She was sitting still as a mouse, ma’am. Did you teach her to always sit still if she ever got lost? That was wise. She was watching a crack in a rock with the tiniest little—”

“Waterfall,” Campbell said, pulling Merry back into her lap, holding her close, inhaling the heavy scent of pine that rose from her daughter’s sweet head. “Thank you. Thank you so much.”

“Exactly,” the heavyset officer continued. “You know the place, then.”

“Her sister knows,” Campbell told him. She smiled across the yard at her mother-in-law as the relatives swept forward. The older woman nodded, the fingers of both her hands lifted, the fingertips meeting at her lips in a kiss.

THE LAST BEST NIGHT

Two nights before New Year’s Day, which would be her thirteenth birthday, Mallory Brynn was certain that she died before she could wake.

The burning golden panel of cloth fell on her like a great web, sealing her in a searing cocoon. When she tried to breathe, the filaments and sizzling threads of the fabric scorched her throat. Her lungs collapsed into charred, useless flaps. Her last thoughts were of Adam, so little, and her younger cousins. She was sure that Meredith had gotten out with them in time. . . .

“Sit up!” Meredith shouted. Mallory mumbled, her hands flailing, still fighting the dream. “Mally!” Meredith said again. “I’ve tried to wake you up three times! Could you be more limp? Do you really want to sleep through your own birthday party?”

“Oh my God!” Mally whispered, sitting up and pinching her forearms to verify that she was still flesh and bone and not ash. “I forgot all about it. I had the most horrible dream! I dreamed I died in a fire, Merry. I dreamed I was dead.”

“You were out of it like you were dead, Mallory! I hate when you go random like this. You just don’t care.”

“I’m tired from practice,” Mallory, who played indoor soccer in the off-season, said. She pulled off her socks and added, “Plus, I hate parties.”

She did not, but she was so deeply shy that being introduced was, for her, like being scraped with the tines of a fork.

“You hate parties? How can we be related?”

“I just . . . don’t know what to say. I can’t say, ‘Oh, Alli’s wearing white and so is Crystal. How totally dorky, hanging with the trendies,’ “ Mally simpered in what she considered a good imitation of her sister’s friends.

“My friends don’t talk like that.”

“They do so.”

“So do yours.”

“I don’t have any friends like that,” Mallory said.

Merry realized, with a pang of sympathy, that this was true. Now that they were in junior high, boys didn’t want to hang with Mally for the same reasons she still wanted to hang with them. Mallory’s best friends were high-school girls from the Eighty-Niners, the traveling soccer squad. They liked her enough. But there was no such thing as a high-school girl who would want to sleep over with a thirteen-year-old if she wasn’t babysitting her.

“Well, when you see people, just say, ‘Thanks for the present,’ “Merry said, soldiering on. “Say, ‘Thanks for coming.’ Are you stupid or something?”

“We told them not to bring presents.”

“But nobody pays attention to that. They’ll bring some anyway,” Meredith said hopefully, examining her reflection in the long mirror their father had glued to the back of their door. Her blunt-cut black hair shone like a new boot. A box-pleated melon miniskirt, the light wool tweed crisscrossed with pale blue strands, worn over white tights, topped off by a cami and a man’s blue twill cuffed shirt, matched her alternating white-and-melon fingertips and toes perfectly. She sighed in hard-earned pleasure. It had taken four hours at the Deptford Mall—an expedition that would have excited Mallory as much as shopping for batteries. But the effect was worth it—casual, not too on-purpose, dressed up a little bit by the three matching pearl studs their parents had given each girl. Their mother had pierced their ears—taking care to put two holes in Mallory’s left ear and two in Meredith’s right ear—to tell them apart. A trio of tiny, perfect pearl studs was their parents’ present to each girl.

When the girls turned out to be mirror twins, and the piercings corresponded to the correct side for each girl, Campbell was astonished. When she’d chosen the spots for the piercings, she’d had no idea.

Merry wondered for a moment if she should ditch her pearls for her white-bead chandeliers. But that would hurt their parents’ feelings.

Mally was wearing her pearls. That was at least a start.

So Meredith ransacked her sister’s closet. There were only two remotely possible shirts. The best hope was a cream-colored thing with a hint of a ruffle at the shoulders. It was clearly meant for summer, but Mally could throw it over a long-sleeved tee, if Mally had a tee that didn’t look as if it had gone under the lawn mower. Meredith could lend her a real silk gray turtleneck, but she would spend the whole night watching Mally like a hawk. Mally was such a slob. She threw herself around like an eleven-year-old guy—still! She wore hockey skates! She rode her bike to school in nice weather, to Meredith’s utter humiliation. She slept in Bugs Bunny boxers. Mally’s definition of “dressed up” was wearing something she hadn’t already worn twice—in the same week! And still, all she had to do was brush her hair and zip! Mallory was as beautiful as Merry, except that for Merry it was a full-time job.

Merry was too young to have any idea that all the washing grains and crunches she inflicted on herself were unnecessary—that both girls’ basic elfin cuteness was genetic. She liked seeing herself as a slave to her appearance. It justified how much she spent on things just because she liked how they smelled. It justified the hours she spent simply stroking her soft, textured garments, nearly in tears because they were so beautiful and they would last long after she, Merry, got old and died. She would never have considered it a selfish thing that she locked the box where she kept her jewelry or crossed elastic bands over the front of the shelves where she stored her sweaters, folded in order not just by color but by shade.

She wanted to forbid people to touch her things, but couldn’t bear to admit it. It was at odds with her generally sentimental and loving self—about which she was also vain.

Finally, knowing it would be wrong to let her twin go down to the party looking like a homeless person, she pulled down her silky turtleneck, the color of moonlight on a summer lawn, trying to put the picture of it with a mustard stain on the middle out of her mind.

“Here, Mal,” Merry said. “You can wear this under your nice cream blouse. . . .”

“I hate that blouse. It’s too tight!”

“It’s supposed to be tight, duh! It’s supposed to show you have a waist!”

Mally grumbled as she rolled out of bed and headed for the shower. “I barely do have a waist.”

This was true. At four feet and ten inches, neither of the girls had yet what would be termed “figures.”

Meredith did her best to cinch in at the middle what basically went straight up and back down. Despite the personal distinction she made between herself, a cheerleader, and her sister, a jock, Merry also was a committed and agile athlete. Only eighty-eight pounds, she was the team’s cocaptain and a “flyer,” tossed five feet into the air above the gymnasium floor to land in a basket catch, lifted on the thighs and shoulders of bigger girls of the pyramid.

Mallory emerged from the shower with wet hair and an alarmed expression.

“Why did you have to invite guys?” she asked. “Everyone thinks I’m an idiot. I probably dreamed I was on fire because of unconscious free-floating anxiety or something.”

“Free-floating what? They’re not sleeping over! And no one thinks you’re an idiot,” Meredith explained. “How could they? You never say anything. They probably just think you’re gay.”

“Maybe I am gay.”

“Well, then dress up for the girls. Jeez, Mal. You’re trying to drive me crazy,” Meredith finally said, spinning Mallory around, tucking and fussing. “And it’s working. Stand up straight!”

“Ugh,” Mallory said, and flicked at the ruffles that flattered her strong, broad shoulders. She stood up straight and her natural grace took over. “I look like crap. I wish I was wearing a tracksuit.”

“You look normal, Mal. You’re not used to normal. Most people don’t wear gym shorts in December with T-shirts that have stupid graffiti jokes on them.”

“I love my shirts! Drew gave me those shirts.” The girls’ next-door neighbor was a boy three years older, but had grown up with the twins. When Drew’s mother, Hilary, wanted to torment them, she brought out photos of all three of them wearing diapers and nothing else. Now, Drew had a special place in their hearts because he had recently acquired both his older sister’s Toyota truck and his driver’s license.

Table of contents

Title Page

Copyright

Publisher’s Note

Dedication

LOOK BOTH WAYS

THE LAST BEST NIGHT

UNLUCKY THIRTEEN

FOREVER TWO

HEROES AND VILLAINS

DOUBLE VISIONS

ALONE IN THE MIRROR

MEETING PLACES

NO TAKE BACKS

SICK SENSE

BAITING THE TRAP

A DATE WITH DRAGONS

THE LONELIEST PLACE

HEAR LIES

THE TWO-HEARTED GIFT

Acknowledgments

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)