Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

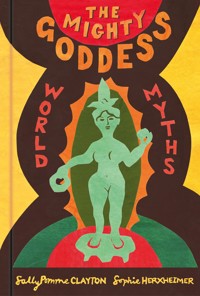

This stunning collection of myths is for adults, and brings together 52 goddess myths from across the globe: familiar, unknown, forgotten - spectacular! Pioneering storyteller Sally Pomme Clayton revitalises powerful goddesses, creating new perspectives and contemporary literature from fragments of myth. It features 52 papercuts by artist Sophie Herxheimer, juxtaposing the ordinary and fabulous. The Mighty Goddess reimagines ancient myths in poetic language, putting the goddess in the centre of the narrative, exploring the diverse ways in which goddesses are represented. Words and images delight and subvert, revelling in the female, exploring creativity, desire, destruction and death. This contemporary collection brings goddesses to life in all their glory. Journey from Alaska to Mesopotamia, and ancient Rome to Tibet, and follow the goddess from creator to crone in a collection where myth and art combine.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 242

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my sister, and all our sisters. SPC

For my daughter, and all our daughters. SH

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Sally Pomme Clayton, 2023

Illustrations © Sophie Herxheimer, 2023

The right of Sally Pomme Clayton to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-80399-298-3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Designed by Jemma Cox

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Journey of the Goddess

CREATOR

Maiden of the Air, Mother of the Water – Finland

Grandmother Spider – Hopi, Southwestern United States of America

Sun Woman – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Northern Territory, Australia

Nut, Sky Goddess – Egypt

Garden Goddess – Dinka, Sudan

Sedna, Goddess of the Sea – Inuit, Arctic

Saule Shining One – Lithuania/Latvia

Primal Mother of the Deep – Mesopotamia

Saraswati, Creator of Creation – India

VIRGIN

Vesta Virgin Flame – Roman

Arianrhod – Wales

Changing Woman – Navajo, Southwestern United States of America

Being Bears for Artemis – Greece

Fair Maid of February – Ireland

Idunn’s Apples – Scandinavia

Morning Star, Evening Star – Lithuania/Latvia

Goddess of the Hunt – Roman

Maiden, Mother of All – Christian

WARRIOR

Battle of Day and Night – Sumeria

Pele, Volcano Goddess – Hawaii

Mistress of Magic, Speaker of Spells – Egypt

Anahita – Iran

Durga Demon-Slayer – India

Pallas Athena – Greece

Amaterasu Sun Goddess – Japan

Sekhmet Lioness – Egypt

Lilith, Goddess of Night – Hebrew

LOVER

Aphrodite, Foam Born – Greece

Sisters in Love and Death – Mesopotamia

The Net of Venus – Roman

Freyja, Goddess of Sex – Scandinavia

Chang’e, Lady of the Moon – China

Aphrodite and Anchises – Greece

Isis and Osiris – Egypt

Erzulie Freda – Vodou, Haiti

Venus and Adonis – Roman

MOTHER

Pachamama – Inca, Andes

Cybele, Magna Mater – Roman

Oshun, Sweet Water – Yoruba, Nigeria

Green Tara – Tibet

Demeter and Persephone – Greece

Queen Mother of the West – China

The Seven Scorpions of Isis – Egypt

Lakshmi, Mother of Prosperity – India

CRONE

Asase Yaa, Old Woman Earth – Ashanti, Ghana

Baba Marta – Bulgaria

Great Lady of the Night – Māori, New Zealand

Fortuna – Roman

Cihuacóatl, Snake Woman – Aztec, Mexico

Cailleach – Ireland

Elli, Old Age – Scandinavia

Hekate, Goddess of the Three Ways – Greece

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Thanks

Journey of the Goddess

The goddess has multiple forms that resonate across the world in one mighty being. The oldest images of the goddess were carved in bone and stone around 40,000 years ago. Myths of the goddess appear and reappear in multiple versions and are both universal and local, containing motifs that are shared by all, while taking cultural and geographically specific forms. These myths are a precious hoard that echo from eternity down into our deepest selves. By bringing these global goddesses together I hope to honour these diverse stories, allowing their images and narratives to reverberate with each other, revealing our shared cultural roots and collective preoccupations. But her myths come with a warning – these stories have not been tamed! They are about lust and greed, rape and rage, death and destruction, jealousy and murder, transformation and rebirth. I have not softened the content but respected it and responded to it, exploring some of its many meanings.

The goddess repeatedly inhabits particular roles, frequently appearing as creator, virgin, warrior, lover, mother, and crone. This book follows the journey of the goddess from creator to crone, and her manifestations in these roles across the world. I have chosen to define the goddess as a supreme deity who is, or was, worshipped. The divine goddess appears as female, both male and female, or transcends gender. I have also chosen to focus on myth rather than fairy tale. Powerful characters, such as Baba Yaga, who have goddess aspects but appear in fairy tales, have not been included – forgive me Baba! Myths and fairy tales have distinct and very different structural patterns. Myth has tangents and back stories, like a family tree that spreads outwards. It has many possible routes through its narratives, with open beginnings and endings. It is linked to ritual and worship, and usually the narratives connect to a wider pantheon of gods and goddess and their stories.

This book is my version of the images and narratives of the one and multiple goddess. I have taken my own journey through the myths, placing the goddess at the centre of each story, not at the side or lost at the end where she often can be. I have sometimes chosen to leave out male characters or reduce their roles – there are plenty of collections where you can find their stories! By telling the myths from the point of view of the goddess I discovered new emotions, meanings and metaphoric realities.

I have been performing many of these myths for nearly forty years: starting as a young storyteller, feeling as though I was not equal to the material, trying to discover how I could bring ancient myths to contemporary audiences, both honouring the material and giving it new life. I continue this exploration. The myths in this collection arose from extensive research, finding multiple versions, looking at artefacts and locations, then weaving my own versions from sometimes disparate fragments of story and history that might not have been brought together before. Some of these versions have also been shaped through repeated performances and by the responses of audiences across the UK and beyond. Audiences help a storyteller find rhythms and patterns in the narrative, they inspire jokes and humour and bring out the drama and characters in a story. This book is a legacy to a life of living with, loving, and performing these myths.

All these myths were once spoken or chanted, some still are. Some of the myths exist as ‘urtexts’ – an earliest version, written on stone walls, clay tablets, papyrus or palm leaf. Most of the myths exist as multiple written versions, collected and transcribed or developed from oral sources, turned into books, translated, made into operas and films, rewritten, then turned back into performances on street corners. I continue this endless process.

I have been shocked to find how little narrative exists for some goddesses. Their stories are absent from even recent collections. I have found that goddesses who are part of major pantheons tend to have more narrative, more has been collected and written down, and more artefacts linked to them exist. While local or household goddesses who are on the edges of pantheons have less narrative, less has been written down and less remains. These goddesses were, and some still are, part of private rituals rather than public worship, they might have important shrines in the home or local landscape, but their lower status seems to mean less has passed from oral to written traditions. I hope their stories will be collected for future generations. For some goddesses very little narrative exists, instead there might be potent images, a few prayers or rituals. Some of these goddesses are so important I wanted to include them here. I looked at statues, patterns on shards of pot, textiles, songs or prayers to find fragments of narrative. Examining what a goddess holds and wears, the gestures she makes, what blessings she confers and what she represents are all clues to her story. Goddesses usually have several epithets (names) that describe her energies and powers. Epithets are a feature of myths, repeated in prayers and praise songs, inscribed on shrines and objects. They are useful in discovering more about a goddess and I have included some of her multiple names to evoke her different attributes.

The goddess often appears in multiple roles, all at the same time, in one myth! I chose which section to place each myth, according to which role was the most dominant. In the ‘Creator’ myths, the goddess often appears in all roles simultaneously. Grandmother Spider is both creator and crone, who spins the world. Sedna is lover, mother, warrior, but, most of all, creator – all the sea creatures are born from her body. The ‘Creator’ myths often have a violent aspect, body parts are cut away, goddesses are destroyed, sky is separated from earth, light from darkness, water from earth, so that something can be born. While the myth of Tiamat, ‘Primal Mother of the Deep’, describes a cosmic battle between male and female power that ends with the goddess’s own body becoming the Earth.

In the ‘Virgin’ myths the goddess often appears as a warrior, passionately choosing virginity, then fiercely defending it. Virgin goddesses often suffer rape and the loss of their precious virginity and then turn to righteous fury and warrior rage. Virgins Arianrhod, Changing Woman and Mary miraculously become mothers. Many of the virgin goddesses are linked to the education of young girls, passing on the values and skills of the virgin.

In the ‘Warrior’ myths the goddess is born from anger that flashes out of an eye, turning into Durga or Sekhmet. Athena is born from Zeus’s head then goes to war with him. Goddesses Lilith and Isis both steal the unknown magic name of the ‘father’ god and gain ultimate power. The power and rage of these goddesses often cannot be stopped, as they defend their people, their land, the planet and the universe.

In the ‘Lover’ myths the goddess becomes creator, her desire and satisfaction spreading fertility across the world. In the myths of Isis, Ishtar and Venus dried sticks burst into blossom, bodies become flowers and trees. As a lover the goddess often becomes a warrior too. Lovers lose their beloved and undertake impossible quests and battles to get them back, while desire turns to vengeance for Freyja and Aphrodite.

In the ‘Mother’ myths the goddess is often the life-giving Earth itself. The mother goddess can also be a virgin, or eternally young, possessing the secret of immortal life. The mother merges with warrior as Isis furiously protects her son, and Demeter’s search for her daughter turns into a curse that punishes the world. The mother goddess, Cybele, transcends gender and all roles, and I have honoured Cybele with no pronouns.

The ‘Crone’ myths link old age with both birth and death, the crone is a mother and her birth canal becomes a tomb. Goddesses Asase Yaa and Hine-nui-te-pō are midwives who cradle the dying soul like a baby, so it can be born again. The crone is also a virgin, giving birth to herself endlessly, as winter becomes spring. Both Mexican Cihuacóatl and Ashanti Asase Yaa are connected to snakes who shed their skin and give eternal life.

Look out for the sparks that flash between these myths! I still find it thrilling and mysterious that so many parallel images, motifs and narrative elements reappear again and again across different cultures, languages and continents. These ancient stories connect us all. You will meet some goddesses and pantheons more than once as the journey of the goddess continues through the collection. I hope this book is a resource that leads you to explore other versions, to find the bits of narrative I have left out, and seek out the many, many other goddess myths I have not told here.

In goddess myths across the world humans often make the same great mistake: they do not recognise the goddess, and they are punished for it, losing the goddess’s blessing and gifts. So, keep alert, the Mighty Goddess is everywhere and in us all. May her images and narratives give us courage, inspiration, and hope.

Maiden of the Air, Mother of the Water

Finland

Forever has always existed. Darkness was always there. And the sea and sky were there too. There was no earth yet or light, just dark sky and rolling sea. In that time there was one girl, one girl all alone. She was Ilmater, Airess, Maiden of the Air. She lived by herself in the smooth, spacious fields of the air. The Wide-Wandering Goddess blew this way and that. For a long time, Airess played in the open meadows of the sky. Then she got bored, something was lacking. Ilmater was all alone and there was nothing for her to rest her feet on!

The Maiden of the Air swooped down and landed on the billows below. Ilmater floated on the empty sea, drifted on dark water without end. Then a blast of wind circled Ilmater. It was a hot wind, a lusty wind and it wrapped around her, pulled her close and squeezed her tight. The wind raised the sea into a foam and rocked the maiden. The wind kept rocking the girl. The wind blew through her, the wind blew into her, the wind blew Ilmater pregnant.

Maiden of the Air became Mother of the Water. She swam through the sea looking for land. She swam north, swam south, swam east, swam west. She was looking for a place to rest, looking for somewhere to give birth. There was nothing but water, no land, no home, nowhere to give birth. Ilmater floated in the darkness carrying her baby for a long time, a very long time. She swam across the sea for seven hundred years, seven hundred years passed and nothing was born.

Then a little bird came. It fluttered about looking for land. The bird flew north, flew south, flew east, flew west. The bird was looking for a place to rest, looking for somewhere to build her nest. There was nothing but water, no land, no home, nowhere to lay her egg. The lonely mother knew just how the bird felt so she raised her knee from the sea. The little bird saw something rise up out of the waves and thought it was a grassy hillock.

The bird swooped down and made her home on the knee of the Wide-Wandering Goddess. The bird pulled long strands of hair from Ilmater’s head and wove them into a nest. And there she laid her egg. A golden egg!

The bird sat on the egg, brooded the egg, turned the egg, warmed the egg. The egg grew hot. Ilmater felt her knee warming, her skin smouldering, her blood boiling, her sinews scorching, her bones melting. She could not help herself, she twitched her knee and the egg fell into the sea. The egg cracked. The golden egg broke into bits, and the bits turned into beautiful things. The universe tumbled out. The egg shell became the land. The egg yolk glowed as the sun. The white of the egg gleamed palely as the moon. The spots on the egg became the clouds. The speckles on the egg became the stars. And so the world was made!

Ilmater pulled herself out of the sea onto dry land. At last Maiden of the Air had found a place to rest, Mother of the Water had a home. The Wide-Wandering Goddess could give birth. We are all the heirs of Airess and that first egg.

This creation myth is from the Finnish epic The Kalevala. This poetic epic contains a series of spells, chants, myths, remedies and stories. It is sung as a duet between two singer-storytellers, one leads and the other follows repeating the last words and phrases. This repetition gives the performance an incantatory feeling.

Grandmother Spider

Hopi, Southwestern United States of America

Grandmother Spider thought, ‘make something!’ She was Thought Old Woman and whatever she thought came into being. She wove things out of nothing, pulling creation out of herself. She thought, ‘Earth is empty, silent, still.’ Grandmother Spider’s thoughts fluttered. She thought of green. She scooped up mud with her slender fingers and spat on it. She mixed soil with saliva and formed her thoughts into the shapes of trees. She thought of orange and blue and shaped birds. She thought of brown and white and formed crawling creatures. She moulded her thoughts into existence and laid the shapes out on the muddy ground. The shapes were silent and still.

Grandmother Spider began to spin, twirling her pointed fingers so silvery threads appeared. She wove lacy capes from her threads, fleecy and soft as clouds. She covered each shape with a white cape, wrapping the shapes in her web of existence. Then she began to sing, murmuring the song of life. The shapes stirred, breathed, rustled, grew, croaked, growled, squealed, cooed, crawled, swam, ran, flew.

Grandmother Spider’s thoughts flickered. She thought of hugging and holding hands, of laughter and song. She took more mud and formed human beings. She wrapped people in her life-giving capes and sang the song of creation over them. She gave humans beating hearts, breath and speech.

Grandmother Spider’s thoughts trembled. She wove long, shimmering threads around the world and set Earth spinning. She tied the ends of the threads to the tallest trees with the deepest roots to hold Earth steady. And spiders have been fixing their webs to trees ever since. The world was alive. Earth was no longer empty, silent, still.

Grandmother Spider has been weaving our fates ever since. She stole fire to keep humans warm. She wove baskets and nets for hunting and carrying. She taught humans how to spin, weave and play string games. She showed the direction in which to turn the spindle so it follows Earth’s rotation. And when Earth was overwhelmed with water and everything flooded Grandmother Spider wove a raft, a silver bridge so animals and humans were saved.

But most of all Thought Old Woman teaches us thought. How keeping the pattern in your mind as you write, draw, compose or weave will help it to appear. And Grandmother Spider is with you, if you just listen. She is hiding behind your ear, guiding you so that you reach the end of your journey. Thought Old Woman is always there, whispering her secret knowledge, showing us how to shape thought.

Stories of Grandmother Spider are found in the living myths and epics of many First Nations, especially in the south-west and along the west coast of North America. In the last paragraph the list of things that Grandmother Spider creates each have multiple versions of stories.

Sun Woman

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Northern Territory, Australia

Wuriunpranilli makes a fire. Twigs smoulder and the first rays of dawn streak across the sky. She scrapes up red ochre, dips her finger into the dust and draws patterns across her body. She decorates herself with red dust, covers herself with red dots, red rays, red flames, red spirals, red circles. She cloaks herself in the land itself. The patterns begin to gleam, to move, to swirl and red ochre rises into the air. Red dust scatters and sparkles, becoming particles of light. The clouds turn red. The sunrise is on its way!

Wuriunpranilli twists bark into a torch and holds it to the fire. The torch catches and begins to burn. She lifts her torch high and sets off. Sun Woman walks up into the sky, her torch fills earth with light and she walks from east to west. Birds follow her, singing, calling up the morning. Her torch blazes as she journeys across the sky. It is burning hot at midday, then her fire fades and Sun Woman climbs down into the western horizon. She gathers twigs and lights a new fire. She scoops up red ochre and paints fresh patterns on her skin. Red dust rises, scattering, and the sky glows red. The sunset is on its way!

Birds stop singing, fluff up their feathers and go to sleep. But Wuriunpranilli does not sleep. She continues her journey. She clambers down a dark hole into a tunnel under the earth. She walks all night through the tunnel that connects west with east. She walks all the way back to her morning camp. And there Sun Woman lights her fire again and paints her body with spirals of blood and fire, circles of earth and air. In her endless cycle of rising and setting, living and dying, Sun Woman brings us all heat, light, life, forever.

Wuriunpranilli is a solar goddess who is part of the profound sacred mythologies and living traditions of the indigenous peoples of Australia. This is my interpretation inspired by several versions and the brilliant essay ‘Australian Aboriginal Myth’ by Isobel White and Helen Payne in The Feminist Companion to Mythology edited by Carolyne Larrington.

Nut, Sky Goddess

Egypt

Nut curves across space, her body arches up and over, as she balances on her fingertips and toes. Her body is sprinkled with stars. The Milky Way streams across her belly and breasts, along her arms, down her thighs and calves. The moon glitters in her hair. The Sky Goddess protects the world, all beneath are held in her embrace. Stretched out below is Geb, God of Earth. He lies on his side, one hand supporting his head the other hand resting on his knee. His body nurtures life. Forests grow from his thighs, mountains rise from his back, lakes flow from his lap, deserts spread across his shoulders.

Nut and Geb were created by Sun God Ra from his own potent semen, his own vigorous spit. The Sun God sails across Nut’s body every day in his golden boat of a million years. Ra embarks early in the morning when he is just a small boy with golden hair. He sails across the Sky Goddess and by the middle of the day Ra has become a burning warrior. By the end of the day Ra is a trembling old man with bright white hair. Goddess Nut opens her mouth and swallows Ra. He continues his journey travelling through the night of Nut’s body, through darkness to dawn. Then Nut gives birth to Ra. The Sun God is born again, a golden-haired baby. And the sky has been stained with the ruddy flood of Nut’s afterbirth, the rosy glow of dawn, ever since.

Nut arched over Geb and was forever filled with desire. The Sky Goddess was eternally looking down on the God of Earth and was consumed by longing. Until she could resist him no longer. She waited until Ra was travelling though the dark of her body then slipped down to earth. She lay down on top of Geb, at last they held each other, embracing so tightly that nothing could come between them. Sky and Earth coupled and Nut conceived.

Nut’s belly began to swell and Ra cursed her, ‘I did not create you to couple. I did not create you to conceive. You will never give birth. Not on any day, of any week, of any month, of any year.’

Nut’s belly grew large and round and hard as stone. She howled in pain and her cries echoed across the universe. But she could not give birth, not on any day, week, month, year.

Thoth, God of Justice, scribe to the gods, with the head of a black ibis and curving beak, heard her cries. ‘This is not justice,’ he said. ‘If Sun will not help, Moon will.’

Thoth knew Moon loved playing chess. He set up the board and arranged the pieces.

Moon glittered, ‘Let’s place bets,’ she said. She was sure she would win. ‘I will stake a tiny portion of my light.’

‘Then I will give a drop of my wisdom,’ said Thoth.

The game began. Thoth played as if he was at war storming across the board mercilessly taking Moon’s pieces one by one, pressing Moon to a murderous endgame. Then checkmate! Moon lost. Thoth collected his winnings, a sliver of moonlight.

The God of Justice carried the moonlight to Nut.

‘This light does not belong to any day, of any week, of any month, of any year. Use it to give birth.’

In the silver light, the tiny slip of time, Nut gave birth. She was relieved of her great burden and gave birth to four children, two males, Osiris and Set, and two females, Isis and Nepthys. Nut had brought the four great gods of Egypt into being. But ever since then Moon has waxed and waned each month because she lost a tiny bit of her light and will never get it back.

Garden Goddess

Dinka, Sudan

Lush increase, green flourish, make our gardens grow Abuk. First Woman teach us how to dig and plant, to water and tend. Garden Goddess show us how to spread fertility across the world.

Abuk was there from the beginning when sky was so close to earth a rope connected the two realms. First Woman Abuk and First Man Garang could climb up the rope into the sky whenever they liked. They visited Sky God Nhialic and his infinite pile of seeds. Sky God would pick out a kernel of corn or a grain of millet and give first humans one seed each. Abuk and Garang would plant, harvest and grind their single stalk of grain. They took care when they were digging the ground or tending their tiny crop, because sky was so close to earth they did not want to strike the great Nhialic by accident.

There was barely enough food for two and when children were born the first family went hungry. Abuk raged, ‘Sky God wants us to starve. Nhialic desires earth to be barren.’

Abuk was filled with grit. And the next time they climbed the rope, as Sky God gave First Man a grain of millet, Abuk bent and seized a handful of seeds and tucked them into her dress. This time she dug the ground deeper and wider and planted all her seeds. Corn grew, millet spread thick, green, golden. There would be enough food for them all.

Abuk raised her staff to harvest the crop, grit had produced goodness. She was so excited she forgot to take care of the sky. Her staff cut through corn and clouds, and struck Nhialic on his big toe!

The Sky God let out a cry, ‘Curse you below!’

Nhialic began to pull up the rope.

‘May you suffer pain just like me!’

Nhialic kept on pulling up the rope, until sky was separated from earth. ‘I leave you all down there, to die alone.’

Nhialic set the sky free, and it floated upwards, far away from earth. And the sky has been a long, very long way from earth ever since. And from that moment onwards all humans have suffered pain, and each one of us faces death on our own.

Abuk tilled the soil, watered and tended her crops. Her harvest was abundant and she fed her family. After the harvest Abuk collected the seeds and named each one for the future. Abuk gave her seeds to the world so that life would continue. Then she taught her children the skills of cultivation.

The ancestors of Abuk wove stalks of wheat into a crown, decorating it with fragrant flowers and placed it on Abuk’s head. ‘Garden Goddess spread green across the world. Abuk make our gardens grow in plots and pots, windowsills and allotments, backyards and tubs, parks and commons, fields and furrows. Garden Goddess make lush increase, green flourish, spread fertility across the world.’

Versions of this myth are found in many countries and cultures across Africa, especially in Nigeria and Ghana. One version includes the Goddess Asase Yaa.

Sedna, Goddess of the Sea

Inuit, Arctic

Sedna gave birth to the sea creatures from her body. They are her children, she cares for them and calls us to care too.

In the beginning the ocean was empty and there were no sea creatures. In those days Sedna lived by the icy sea with her five brothers. She had long black plaits, rosy cheeks and many suitors. She refused them all. No one matched her brothers. Sedna spent the summer hunting moose and caribou alongside her brothers, and when winter came feasted with them beside the fire. When the meat ran out, there were no fish to catch, and so they would often go hungry until spring.

One day Raven flew across the world looking for a wife. His beady eyes spied Sedna. ‘She is for me!’ Raven – shapeshifter, trickster, god, king – fluttered his wings and there stood a man with raven black hair, reindeer skin boots and a parka of white wolverine fur. He looked at his reflection in the sea. ‘Tasty,’ he preened. ‘Except the eyes.’

His eyes were still beady bird’s eyes. Raven stamped his foot and a pair of snow-goggles appeared made of white bone with a tiny slit for each eye. He put them on.

‘She’ll never know,’ he squawked. Then he called up a canoe and paddled across the bay.