Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

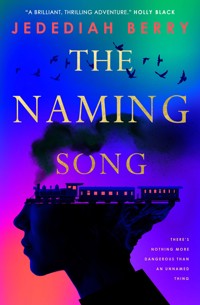

In a world where words are power, there is nothing more dangerous than an unnamed thing. Enter an epic world of ghosts and monsters, magical trains and nameless wonders in this gorgeous lyrical fantasy, perfect for fans of Susanna Clarke, The Starless Sea and the films of Guillermo del Toro. When something fell from the something tree, all the words went away. And the world changed. Monsters slipped from dreams. The land began to shift and ghosts wandered the world in trances. Only with the rise of the named and their committees―Maps, Ghosts, Dreams, and Names―could humanity stand against the terrors of the nameless wilds. Now, they build borders, shackle ghosts and hunt monsters. The nameless are to be fought, and feared. One unnamed courier of the names committee travels aboard the Number Twelve train, assigning names to the people and things that need them. Her position on the train grants her safety in a world that otherwise fears her. But when she accidentally pulls a monster from a dream, and attacks by the nameless rock the Number Twelve, she is forced to flee. Accompanied by a patchwork ghost, a fretful monster, and a nameless animal who prowls the borders between realities, she sets out to look for her long-lost sister. Her search for the truth of her own life opens the door to a revolutionary future―for the words she carries will reshape the world. At once a love letter to the power of language and an exploration of its limits, The Naming Song is the perfect fantasy for anyone who's ever dreamed of a stranger, freer, more magical world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 785

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

The Word For Trouble

The Black Square Show

The Farthest Border

The Named World

Acknowledgments

About the Author

PRAISE FOR THE NAMING SONG

“At the heart of this brilliant, thrilling adventure is an exploration of the power of words to transform the way we see ourselves, our history, and our possible futures. The Naming Song understands the fundamental magic of language, and breathes that magic onto every page.”

Holly Black, number one Sunday Times and New York Times bestselling author of The Book of Night

“A breathlessly enjoyable tale.”

Cassandra Clare, Sunday Times and New York Times bestselling author of Sword Catcher

“The Naming Song is a wonder. A masterful, marvel-filled journey of language and ghosts, of monsters and meaning and mystery. This is a haunting, glorious train ride of a novel that feels both new and old at the same time, a creature of post-apocalyptic myth.”

Erin Morgenstern, Sunday Times bestselling author of The Starless Sea and The Night Circus

“Every writer, of course, must make magic out of words—but in The Naming Song Jedediah Berry makes strange and wonderful magic out of the absence of words. This book is a parade of delights and nightmares, written with the kind of incantatory precision that the truest spells are made of.”

Kelly Link, author of the Pulitzer Prize finalist Get In Trouble

“Deeply immersive, magnificently imagined, Jedediah Berry's The Naming Song is an epic tale of the fantastic, where language—quite literally—has the power to remake the world. This is a vast and sweeping wonder of a novel.”

J. M. Miro, bestselling author of Ordinary Monsters

“With The Naming Song, Jedediah Berry offers a Genesis wrapped up in a Revelation—a mysterious, poetic, and invigorating post-apocalyptic adventure saga about how things can be reborn, and in some cases remade, after they have been undone. It's rare that a novel this substantial is also this strange and this fun.”

Kevin Brockmeier, author of The Ghost Variations

“In Jedediah Berry’s The Naming Song I perceive the simplicity and complexity of Richard Brautigan’s Watermelon Sugar, a structure that could have been borrowed from Berry’s own card game, The Family Arcana, and a nod to The Romance of the Rose. Still, it’s wholly its own engaging creature that engenders wonder and suggests a new kind of fiction.”

Jeffrey Ford, World Fantasy Award-winning author of The Shadow Year

“Berry creates both a familiar and unfamiliar landscape in a sweeping epic about the language and love between us, the humanity of the living and the dead, and the raw power of creation.”

J. R. Dawson, author of The First Bright Thing

“An anti-totalitarian, post-apocalyptic fable featuring mystical theater trains, impossible monsters, and the awesome power of story? Sign me the heck up. If we can rise against injustice even half as boldly as “the courier” and her friends, there might just be hope for humanity yet. Jedediah Berry has delivered a true epic, thrumming with life.”

GennaRose Nethercott, author of Thistlefoot and The Lumberjack's Dove

“The Naming Song is not just one of the best told fantasy novels of the last twenty-five years, it is a masterpiece of storytelling destined to be extolled as a classic.”

Howard Andrew Jones, author of Lord of a Shattered Land and The Desert of Souls

“Fans of Patricia A. McKillip’s The Forgotten Beasts of Eld or Marie Brennan’s Driftwood will be in awe of Berry’s (The Manual of Detection) wonderfully odd ode to language, story, and family.”

Library Journal, starred review

“Fantasy readers looking for a fresh and exciting new world to explore will be thrilled.”

Publishers Weekly

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Naming Song

Print edition ISBN: 9781835413937

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835413944

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: March 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Jedediah Berry 2024

Jedediah Berry asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)

eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, Estonia

[email protected], +3375690241

Typeset in Arno Pro 10.7/14pt.

For my sister Cait

A MAP OF

THE NAMED TERRITORIES

FEATURING

ALL MAJOR TOWNS, CITIES, AND ROUTES

*As prepared by the maps committee andapproved by its chair for general distribution

Travel beyond the borders marked on this map is forbidden. Failure to report discovery of unnamedlocations within these boundaries is punishable in accordance with the laws of the sayers.

PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

THE NUMBER TWELVE

The courier. A member of the names committee, tasked with delivering new words.

Book. The chair of the names committee, who brought the courier aboard.

Beryl. The diviner who finds words for machines and their parts.

Rope. The diviner who finds words for flying things.

Ivy. A courier who witnessed a vicious attack on Buckle Station.

The patchwork ghost. The courier’s oldest friend.

The stowaway. A fierce hunter of vermin.

STEM

Lock. The courier’s father, a researcher of ghosts and monsters.

Ticket. The courier’s sister, who never responds to her letters.

THE BLACK SQUARE SHOW

The Gardener of Stones. The director of the show.

The Gardener of Leaves. A monster who guards the Black Square’s train.

The Gardener of Shovels. A quiet woman who supervises the making of costumes and sets.

The Gardener of Trees. Pilots the Black Square’s train and oversees the writing of stories.

The Two of Shovels. A monster who resembles the courier’s sister.

The Seven of Stones. A brilliant performer.

The Six of Trees. A difficult young man who writes stories.

The Scout of Stones. A ghost who operates the light machine.

THE DELETION COMMITTEE

Frost. A sayer, rising in power.

Smoke. Frost’s speaker.

The seekers. A pair of very old ghosts, identical and relentless.

HOLLOW

The glassblowers. A group of skilled artisans.

The junk dealer. A buyer and seller of nameless goods.

OLD WHISPER

Hand. The first namer.

Moon. The second namer, first courier of the names committee.

Needle. A child, precious to Hand and Moon.

The scavengers. Among the first named, seekers of useful objects in piles of nameless junk.

Bone, Blue, and the other one. Elders who were children when something fell from the something tree, they remember stories from before the Silence.

THE

WORD

FOR

TROUBLE

She delivered echo. She delivered echo into a nameless gorge at the edge of everything she knew. Water dripped from rock walls and from the limbs of trees by the river down there. She called out the word, and the word rolled back to her three, four, five times, the thing calling itself by name: echo.

Birds flew out of the gorge. One of the men who’d followed from Jawbone spoke echo quiet to himself. He said the word sounded strange to him.

“They always sound strange at first,” she said.

* * *

She delivered stowaway. She climbed aboard a freight train, hid herself in one of the boxcars, dozed as the train rolled east along the canal.

The doors slid open to gray light and the rumble of Hollow’s factories. Two watchers peered inside, ghost lenses flashing. She let one of the watchers see her, and he reached for his signal box. Before he could break it open, she stood and spoke the word for the thing she was, stowaway.

The watchers spoke the new word, to her and to each other, until they were sure they had it right. Then they helped her down out of the car. The watchers were happy to have a word for those people. Easier to catch them that way.

* * *

She delivered brass. In an empty house at the edge of Tooth, she found a brass doorknob, a dented brass bowl, a brass cup. She tested their weight, felt the metal grow warm in her hands. She filled the cup with water from her canteen and drank. With the taste of brass still on her tongue, she went outside and made the delivery.

From boxes and trunks, out of attics and basements, people brought brass clocks, brass locks, brass toys, brass rings for the fingers, wrists, and neck. Some made noise with brass horns while others covered their ears or smiled and shook their heads. Nobody knew how to play.

From the factories of Hollow came new things of brass. The couriers of the names committee were issued brass buttons for their uniforms. She sat alone at her desk, working with heavy thread.

* * *

She delivered moth. She wrote in her report that she had seen many kinds of moth out there. More kinds of moth, maybe, than they had numbers to number them with.

The diviner who found names for flying things sat with her at the morning meal. His name was Rope, and his arms were long with ropy muscles, and he used a length of knotted rope for a belt.

“We’re still finding more birds after all these years,” Rope said. “Moth could be bird all over again.”

She wasn’t sure how long Rope had been with the committee. Sometimes, when she saw Rope, it took her a moment to remember who he was.

“Starling, kestrel, magpie,” Rope said, rubbing his head as though the birds were within, trying to peck their way free. His pale hair was bristly, like frayed rope. “And those are just this month.”

He was often like this, she remembered. Unhappy and a little resentful. Was it because the others forgot about him, too?

“You seem tired,” she said.

Rope sighed and said, “Hard to sleep some nights. Especially since Buckle.”

“I try not to think about Buckle,” she said—trying, as she said it, not to think about Buckle.

“It’s best not to think about Buckle,” Rope agreed.

* * *

She delivered harrow. An old farmer had built one out of scrap and railroad spikes. It was a new thing, or a thing from before that was back again, which was probably more dangerous.

On the southern border, at the foot of a nameless mountain west of the Well-Named Mountains, the courier found the farmer in her barn. She was making modifications with a naphtha torch. The thing was all shadows and sharp points in flashes of hot light.

The farmer lifted her mask. Juniper, her name was. She looked at the courier’s uniform and said nothing.

The courier helped her hitch the heavy frame to an old horse. Juniper had no ghosts to work her land. Out in the fields, the courier walked behind, feeling the softness of the broken soil under her boots. She took an unbroken clod in her hand and broke it. She spoke the word for the thing the farmer had built, harrow.

Juniper did not repeat the word aloud, the way people usually did.

The courier told her that she should have filed a request. The sayers rarely made exceptions these days. “They told my committee to send someone,” the courier said. “They could have sent some of their own.”

Still Juniper said nothing. But she took the courier inside and set out two bowls, filled them with potato and onion soup. A moth flew in loops around the lantern while they ate.

* * *

She delivered whiskey. A sayer’s son had distilled barrels of the stuff in an old granary, then sent jars to senior members of the committees. Samples for your inspection, he wrote.

Book invited the courier to his office to share his portion of the nameless spirit. “Obviously a bribe,” he said, turning the jar in his hand. “Wouldn’t be right to drink it alone.”

Book served as chair of the names committee. He decorated his office with purple fabric and soft pillows. He owned a stack of phonograph records from before the Silence, along with a phonograph to play them on. He wore gray suits and vests, purple ties and handkerchiefs. There had been no word for handkerchiefs until Book himself requested one from the diviners, so he could stop calling it “that rag I keep in my jacket pocket.” There had been no word purple until Book delivered it, back in his own days as a courier.

“Let’s drink until we’re both of us shabby,” Book said. Another courier had just delivered shabby, and Book liked to use the newest words. He liked to stretch them where he could.

They drank from small tin cups. Book smoked tobacco wrapped in dried tobacco leaves. He had told the diviners to take their time with that one, because sometimes Book liked the taste of something nameless.

He winced with each sip and was happy. As they drank, he told the courier about the assignment. Told her where the young man kept his still. Gave her an envelope containing the card on which was inked the word, divined by a diviner but still unspoken, unspeakable until a courier made the delivery.

“You know I’ll just have to drink more when I get there,” she said.

“Then you’ll need the practice,” Book said, refilling her cup.

The courier sank back into the cushions and Book put his feet up on his desk. It was late; most of the committee was asleep. Book wore gray slippers, his softest pair.

“You’re keeping up on your training?” he said. “Keeping fit?”

She was. The courier trained every day. She stretched and lifted weights and ran end to end in the committee’s small gymnasium. She read and read again what the old couriers had written down. Moon’s Words on Paper, Glove’s Deliveries—those texts she could recite from memory. She was the best the committee had, and Book knew it.

“I could deliver this right here,” she said.

“Better to go out and make a show of it,” Book said. “We can’t let the sayers think that what we do is easy.”

“Let the sayers think what they want,” she said.

Book frowned. He did not like this kind of talk. The sayers stood above all the named, and what they said was law. More than that: their words were the shape of the world.

So he switched to his favorite subject, the latest gossip about the other committees. A daughter of the maps committee chair had run off and taken up residence in the nameless quarters of Hollow, among the thieves and poets whose stray dreams slipped from open windows to wander the streets.

“Of those kids I am perhaps a little jealous,” Book admitted.

He smiled, but the courier could tell that something was troubling him. Not this assignment, not the other committees, not runaways. Something about Buckle, maybe. Something about her. She started to ask, but he downed the last of the liquor and interrupted her with a loud sigh. “I hope it’s still this good after you’ve stuck a name to it,” he said.

They both knew it wouldn’t be.

* * *

She delivered float. She lay face-up in water and let her legs dangle. She listened to her own breathing. She had done this as a child, in the pond behind the cottage where her father had studied ghosts and nameless things. Now, in another pond on the other side of the named territories, yellow leaves fell from maples and landed on the water. The sun warmed her face and belly, but the water was cold. It rippled from her shivering.

A crowd of people watched from the shore. The water made their voices small. Fish tapped her feet with their mouths. She lay there long enough to forget what she was doing. Then she spoke the word, swam ashore, and put her clothes on.

Float, floating, floated, floats. Once the word was delivered, anyone could speak it, or change it a little to suit what they needed to say. She floated. We saw her floating.

Her committee employed diviners to find the words in their quiet chambers, using tools and methods known only to them. Couriers to deliver the words into the world. Committee pages to add the words to the next broadsheet, to print and carry copies to every place with a name. To Whisper, home of the sayers. To Hollow, the largest city of the named, with its booming factories. To Tooth in the Well-Named Mountains, and to Tortoise on the shore of the Lake. To the cities built on top of cities from before; to the towns cobbled long ago from the nameless nothing; to the new towns on the borders, where settlers waited anxiously for words, because words were a better defense against those for whom the watchers watched than all their guns and palisades.

A cloud floats. Leaves float. The body floated.

She felt that the world might not keep a strong enough hold on her. A new word was a welcome weight, and each kept her stuck more firmly to the ground. But float, when she delivered it, was the opposite of weight. When she delivered float, the people laughed to hear it. They went into the pond themselves, some clothed and some naked, to say float while they floated, in spite of the cold. It worried her, how easy float had been.

* * *

She delivered a name for the ninth month. She went out on the first day and wandered. She watched what people did this time of year, and some stopped what they were doing. Stopped canning vegetables, stopped carrying wood, stopped sewing and tinkering and shoveling. They left fields and mills, left dream scraps drifting in the corners of their rooms. They followed the courier. They wanted to know how it would go. They wanted to be the first to hear.

From charts discovered on walls of structures built before the Silence, the named knew that the year was divided into twelve parts. It was the courier Glove who had delivered month and then, in his later years, names for most of those months. He had needed no diviner because he named the months for named things, as towns and people were named. Under, Ink, Copse,Cloud . . . But each time he named a month, he found it harder to deliver a name for the next. Now Glove was over one hundred years a ghost, and still the month between Axe and Stone eluded the committee. The named called it After Axe, but that was not its name. These were dangerous weeks, a span of time that made the nameless bold.

The courier wandered in the hills and in the forests, and the others followed her. They walked the rails, and for a while they followed the River. Rain fell, and she listened to the sound their boots made. She felt the bite of the wind on her face and hands.

In a frigid gully, among tall pines, she stopped walking. It was the last day of the month. She told the others what name to call it by. Light.

They were surprised. This time of year, light was something they had less of every day. They were cold and tired from their journey, but few of them left when the courier left. Most made fires by the banks of the stream there, and they hung lanterns in the pines. They tinkered and shoveled and chopped wood and built shelters. Later, when the sayers said that what lay in this gully was a village, another courier came and named it after the month of its founding.

The people who lived in the village had a saying: In Light, even the dark feels at home.

* * *

For the courier, home was with the names committee, aboard the train called the Number Twelve.

In the booths of the eating car, and between the broad windows of the common car, namers and crew gathered late into the night. They drank beer and wine and mugs of hot tea. Some brought fiddles and drums, and they had a piano, the one to which the courier Glove had delivered the word piano. The piano was never quite in tune.

In the kitchen car, cooks worked the ovens while ghosts carried water and cleaned, ducking the pots swinging from hooks. Whenever there was music in the common cars, some of the cooks came out to listen. One had a very good voice, and others would call for him to sing. A favorite was the song about the soldier who went over the border to fight the nameless, then went so far he forgot every word but the name of a woman whose smile still shone in his mind—but even that wasn’t enough to bring him home.

Most days, though, few spoke above the creak and rumble of their ancient rolling home. Mahogany tables gleamed under the shaded naphtha lamps of the conference car. In the garden car, rain leaked through gaps between the ceiling’s glass panels, dripping onto plants and onto the plaques that bore their names. In the ghost car, the committee’s off-duty ghosts stared out the windows, or fiddled with the buttons on their dresses and shirts, or dozed in the way only ghosts dozed: perfectly still, emptying of color until you could see right through them.

When the Number Twelve came to a bend, anyone riding toward the back of the train might glimpse the engine out front, black and gold and spewing smoke, the oldest machine on the rails.

From Tortoise near the northern border, the Number Twelve could reach the mining towns of the south in one week. From Jawbone in the rugged hills of the west, four days to Hollow and the east’s green lowlands, its streams and mills. Book and the train’s chief engineer worked in secret to plan their route, keeping mostly to the main lines, constructed before the Silence, maintained now by crews of silent ghosts. The train’s route was always changing, and the committee stayed nowhere for long. That was old law, spoken by the sayers shortly after the founding of the committees—for the safety of the namers, or so they had said.

The other three standing committees—maps, ghosts, dreams—all had offices in Whisper, and in other cities as well. Their members came and went as they pleased, or as their work required. But the namers were the exiles, the strange people, cast out and feared and on the move forever. Moon, the second namer, who divined and delivered ghost and who brought upon the committee its great shame, had written: We do not belong to the world we name. We are only the words we deliver, and then we are not even those.

* * *

The cars closest to the engine were forbidden to the couriers. These were for the diviners and their work, for the chief engineer and the assistant engineers. The courier never went farther up the train than Book’s office, which filled one side of the seventh car.

After each of her assignments, Book summoned her there and kept her up too late. He never went farther from the train than a station bar, and he wanted to hear everything.

“Give me the finer details, won’t you?” he said. “Your reports are so dry I have to take them with whiskey.”

He drank whiskey anyway as she told him about the flying machines of the watchers, gliding silently into dock at the watchtower in Whisper. About dredgers hoisting sunken boats and old ghosts from the poisoned lakes north of Hollow. About the ghost wranglers, rough women and men, leading columns of their quarry from the border to the auction houses of Jawbone.

When she told Book what she saw while out on her last delivery, they could pretend that this was official committee work, part of her report. And when he talked about his own days with a courier’s satchel on his shoulder, they could pretend that it was part of her ongoing training.

Book had delivered official and ongoing. He had delivered perhaps and however, gossip and cajole and grudge, seethe and indulge and dissolute. But of all the words Book had delivered, he was most proud of shadow.

“We didn’t think of shadows as separate from the things that made them,” he said. “We hardly even noticed they were there. The nameless still hide in shadows, but it was worse when shadows weren’t shadow, just places where the light didn’t reach, and no one knew to look for them.”

The old words were gone forever. The diviners of the names committee found new words, arranged glyphs to capture sounds for them. But before a word could be spoken aloud by others, a courier had to speak it first. And to speak a new word, the courier had to know the thing it named. Had to hold it in mind like a perfect glass bead, had to become that bead—and then had to break it. What had Book done to hold, to become, to break shadow? He would never say.

He added a scoop of glittering black naphtha to his stove, and the fire blazed while the wind hurled cold rain against the windows. The courier thought of Hand, the first namer, who had divined and delivered the first word by thrusting one hand into a fire, somewhere in the vast wasteland that was then the whole of the world. Hand, said Hand, naming the thing that burned, naming himself. Or herself: Hand had been neither man nor woman, because there was no he then, no she. Most agreed that if you found the ghost that had been Hand, you would know it only by the scars of that first naming.

Outside, the winds picked up. The Number Twelve rolled alongside a river, the widest river they knew, the one called the Other. The courier knew that towns stood on the other side of the Other, but she could see no towns through the heavy gray rain.

“I wonder if this is what it looked like,” she said to Book. “Just after, I mean.”

“After something fell?” Book said.

“After something fell from the something tree,” she said, which was the closest anyone could get to saying what had happened to make the old words go away.

Book tapped ashes into the tray on his desk and said, “I am pleased to say that I have no idea what it looked like then.” But Book usually knew more than he said.

* * *

Behind Book’s car were the two cars where the couriers had their compartments. Hers was near the middle of the ninth car. Her curtains, stitched from an old dress that had belonged to her mother, billowed when it was warm enough to leave the window open. Now, in the cooler months, she kept windows and curtains closed, and the fabric dyed the light in her compartment blue.

She wrote letters and reports on a desk that folded down from the wall. She kept her satchel on a peg by the door, kept her uniform in the drawer below her bunk. She kept sketches tucked into the bottom of that drawer, and sometimes she took them out and looked at them. In one of the sketches, a man she was supposed to have forgotten stood alongside ghosts in the field, pointing with a stick at something in the dirt. In another, two young girls—she and her sister, who seemed to have forgotten about her—sat at a table with chalk and a slate between them.

The courier did not feel at home here in her compartment, nor amid the cluttered finery of Book’s office. If she thought about it—and the courier did think about it—she knew she felt most at home on the walkways above the couplings, with the wind rushing and the noise of the train pounding at her skin, for that moment it took to pass from one car to the next.

* * *

She delivered names to children. The younger the child, the easier the delivery. At the stations, parents held their children in their arms, rocked them when they cried, waited their turn on the platform. No one called the children nameless, they were only unnamed. The couriers consulted clipboards, looked into the children’s eyes, saw something from which they might hang a word.

At one stop, the courier named the children Ruffle, Scout, Chisel, Loop, and Onion. At another, Bobbin, Dash, Quick, and Bet. She named a set of twins Eager and Echo. She told one mother that her son’s name was Moth.

“You don’t have to give them the newest we have,” one of the other couriers snapped.

The couriers were permitted to use any word secure in the archives of the sayers. Most gave names delivered generations before, words sturdy in people’s minds. Stone, Run, River, Sun, Gather, Bone. The old names stuck better, they said. Kept a person’s feet on the ground.

But the courier chose names she thought the children might ask for if they were old enough to ask. New words with rough edges, names that felt good to shout during games of chase. They had long tethers, those names, and their teachers might struggle with them a little.

As for her name? When the others spoke of her, they called her the courier who delivered trouble. Trouble had been one of her first assignments, and they must have found that fitting. They couldn’t call her by name, because she was the only member of the committee—the only member of any committee—who didn’t have one.

* * *

Her father had known Book when Book still made deliveries. He had known others in the names committee, and even a few of the sayers in Whisper, because of his work for the war effort. His name was Lock, and he would have been able to get her most any name she wanted, any name that fit. She might have been Cup or Whistle. Or Troop, or Cap, or Blue—all names she had favored at one time or another.

But when the Number Twelve stopped in their town, Lock never took her to the station to see the namers. Once, after hearing the train’s strident whistle, she had run to him and begged to go. But he had only crouched beside her, straightened her collar, and said, “The work is more important than any name. Your work, daughter, and mine.”

The work was conducted in Lock’s cottage overlooking the pond. He studied ghosts there—the ghosts of mice and rabbits when he could catch them, the ghosts of people when they weren’t needed in the fields. He also studied the things that escaped from her dreams at night. And sometimes he studied her.

This was the most important part of the work—she could tell by his silence as he affixed the wires to her head and laid her down on the long metal table, which was cold even with the blanket he let her bring from the house. The wires ran across the floor to a row of bulky machines. Lock watched the machines as they blinked and hummed, and their humming followed her into dreams. She came to understand that her dreams were interesting to him only because she did not have a name. That if she were given a name, he might not be interested in her at all.

Years before she was born, Lock had taken her older sister to see the couriers of the Number Twelve. Ticket, her sister’s name was. A sly, quick-moving girl with black wavy hair and freckles on her nose and cheeks. At the edge of the wood, in the shadows of the trees, Ticket had recited old naming songs as though she had invented them—which was, she said, the best way to recite them.

The bear is woolly and full of blood.

Red is the blossom, red was the bud.

Ticket had gone to creche in Whisper, where she sang those songs alongside the daughters and sons of sayers. When she returned home to begin her schooling, she pretended not to see the unnamed little girl, who had appeared in their house just when their mother had become a ghost. The girl understood that this had not been a fair trade—that Ticket would gladly have given up her sister to get their mother back. And if the girl asked questions about their mother, Ticket would only tilt her head and frown, as though to say, Did I hear something? Then she would return to whatever she was doing—sewing or drawing or looking at maps.

At night, the girl the courier had been would speak her sister’s name to herself, whispering so that Ticket wouldn’t hear from the other side of their shared room. The girl imagined she could keep her sister with her forever, just so long as she remembered the shape of her name. Ticket was proud of that name. She collected train ticket stubs and put them in an album with the word Ticket written on the cover. “You need a ticket to get anywhere,” Ticket liked to say.

Now, seated at the desk in her compartment to write another letter, the courier asked about that album.

Do you still add new stubs when you find them, or are the pages full? Does it sit on a shelf beside the letters I write? Or do you toss my letters straight into the fire, so you can read the flames the way I read your silence?

* * *

She delivered walnut. She sat at the edge of a field, in the shadow of the tree she’d chosen for the delivery. The cold had turned its leaves bright yellow.

She ran her fingers along the hollows and ridges of the bark. She gathered the fallen fruit, tore the green hulls, broke shells with a rock, smelled and tasted the soft, sharp kernels.

With her back to the tree, she sharpened the axe she had borrowed from a workshop in the nearest village. She thought she could hear the tree hold its breath.

She swung the axe and felt its bite. She put her face to the wound and breathed the smell of the sapwood. She cut deeper and breathed the smell of the heartwood. She cut deeper and opened the tree’s dark pith. In spite of the cold, she began to sweat. She took off her coat and kept swinging.

The people of the nearest village gathered to watch. When the tree fell, the noise of its falling seemed to come from everywhere at once. Into the silence that followed, the courier spoke its name.

“Walnut,” the villagers said, trying it out for themselves. They wanted to hear it in their own voices. They wanted to say they had been among the first.

The courier returned the borrowed axe and put her coat back on. She left the wood for the villagers to cut and gather, but she kept one of the seeds—wrapped it up tight in a handkerchief and tucked it into her satchel.

* * *

She brought the walnut seed home to her ghost.

The ghost was called the patchwork ghost, and he looked like a skinny man Book’s age or a little older. He wore a gray suit and hat. Both had been patched so many times that the gray was barely visible. The ghost’s patches were brightly colored: red, yellow, purple, green. Even some of the patches had patches.

She found the ghost at work in the printing car, where committee pages set type for the newest words and inked them onto broadsheets—dozens of copies for every town in the named territories, hundreds for each of the larger cities. The ghost’s job was to draw things the new words named. He illustrated the broadsheets as quickly as the pages could print them, and the drawings were nearly identical from one sheet to the next.

Seated beside him, the courier unwrapped the walnut seed. The ghost’s eyes brightened. He shoved the broadsheets aside, set the seed on the table, and took a sketchbook from his jacket pocket.

The patchwork ghost had belonged to her father. When Book brought the courier aboard the Number Twelve, she had insisted that the ghost come with her, so Book had made arrangements. Finding a use for the ghost was easy enough. He was the only ghost who knew how to draw.

While the ghost drew the walnut, the courier reviewed the newest words on the broadsheet. For cirrus, he had drawn wisps of cloud above a high mountain peak. For plum, a dark round fruit hanging from a branch. She had tasted a plum shortly after another courier delivered the word. The named would like plums, she thought.

A shadow fell over the words. Three committee pages were standing over her. They were young, two boys and a girl. Their uniforms fit awkwardly, and they looked tired. They had probably stayed up too late, likely together in one of their compartments, maybe with whiskey—some of Book’s stash had recently gone missing. Now they were rushing to finish the broadsides.

The girl’s name was Sun. “He has hundreds left to do,” Sun said. “You can take one when he’s finished.”

The courier wanted to tell the pages that she had delivered half of the words on that broadsheet. That she would take a copy when she wanted one. But then she saw how the boys wouldn’t look at her, saw how Sun’s hands were shaking.

They were frightened of her.

It had been this way since Buckle.

So the courier took a breath and said, “Of course. You all have important work to do.”

She slipped the walnut back into her jacket pocket. The ghost blinked and turned from side to side, overcome with panic. The courier closed his sketchbook and moved the stack of unfinished broadsides in front of him. A moment later, he resumed work on the illustrations. The panic was gone, but so was the brightness in his eyes.

The boys looked relieved and returned to the printing machine. Not Sun, though. Her friend Wheel had been with the courier at Buckle that day. Sun kept her arms folded over her chest, watching the courier until she stood and left.

* * *

In the eating car, the courier listened to the others discuss their assignments. The couriers talked about how long they had been out there, they talked about the word, about the weight of it, about what they had done to make the delivery. They talked about those others, the people without names. How they saw or thought they saw a band of them at the edge of the forest, on the side of the road, by the banks of the river, in the shadows, in the middle of the night. How they felt them watching, following.

And they talked about Buckle.

She tried not to listen. But Ivy, who had also been there that day, was seated at the table across the aisle, telling her audience how it happened. How she had been about to leave Buckle Station with a new word in her satchel. It should have been an easy one, Ivy said. But to speak the word now made her shudder.

“Imagine, after seeing what I saw, having to deliver giggle.”

The other couriers at her table shook their heads.

Ivy kept her straight yellow hair cut to her jawline, kept her uniform pressed and neat. She had a sharp-looking smile and bright green eyes that missed nothing. Ivy had been born on the Number Twelve. She began training for the names committee on her first day back from creche, and she could trace her family line through generations of couriers. Her mother’s mother had marched alongside soldiers on the southern border, naming towns and territories, naming prisoners. Now Ivy, too, had seen firsthand what the nameless could do.

A cold morning early in the month of Ink. At Buckle, a quarrying town on the canal called the Ribbon, the namers let off five of their own, an unusually high number. Ivy, the courier, and three committee pages.

The courier had gone to the watchers on the platform to show them her papers. She had lingered long enough to let Ivy get ahead, knowing she wouldn’t want company. Once the three pages were cleared, she walked behind them into the station.

The pages’ satchels were full of broadsheets, and they laughed at how strange it felt to walk on steady ground after so many weeks aboard the train. They would travel together through Buckle, then split up to cover the smaller towns along the canal.

Wheel was the eldest of the three. She hoped to become a diviner someday. Paw never wanted to be anything but a page, though he preferred working the press to delivering broadsides. Thumb had just celebrated his fourteenth name day. He was the youngest member of the committee, and Buckle was his first assignment.

They had just gone out among the benches when the nameless appeared. They slipped into the green light of the station, shadows dividing from shadow. They were seven or eight in number, faces hidden behind plain white masks.

Later, some people would say that monsters had come with the nameless, but Ivy and the courier agreed on this much: there was only the one monster. It looked like a round mushroom the size of a child, but shiny, like something made of glass.

Two of the nameless carried the monster between them. At first the courier didn’t think it was dangerous. She’d thought it was something the nameless had captured. She’d thought it was afraid—and maybe it was.

They set the monster on the floor in the middle of the station. One of them knelt beside it and did something. Nudged it, maybe, or caressed it. The courier couldn’t see clearly, and Ivy was already at the door to the street.

Now Ivy said to the others, “At first I mistook the screams for a train braking. I turned just in time to see what was really happening.”

When the monster woke, it expanded. A thing like a living detonation, gathering the glassy stuff of itself into spines and sharp edges, jagged stalks unfurling. Without a sound it sliced and bounded, spreading through the station in shuddering bursts, the way ice spreads over glass.

Ivy had been standing just beyond the monster’s reach. The nameless were untouched—as was the courier without a name. Most others in the station fell.

The pages writhed at the courier’s feet, their bodies pierced by spines, slashed by the monster’s knifelike limbs. The courier knelt beside them, reaching first for one and then for another, wanting to hold them, to piece them back together.

“Wheel, Paw, Thumb,” Ivy said. “All ghosts now. And how many others? The two watchers running from their checkpoint, taken apart before they could open their signal boxes. Four machinists waiting for the train to Hollow, ghosts before they understood what was happening.”

The courier had stared at the nameless, their boots on the limestone floor, their rustling gray robes. She saw them see her, saw them blink behind their masks. She felt their minds seeking hers, wondering at what she was. As one they drew their weapons—then turned their backs on her, going for Ivy instead.

The courier remembered thinking how beautiful Ivy looked as the nameless surrounded her. How her eyes flashed in the light that shone through the station windows. The nameless came at her with knives and clubs, and with stranger weapons. Hooked blades, metal bars linked by chains, long poles fitted with spikes. All Ivy had were words and the threat of a name that might stick. The courier admired the sound of her voice, the roughness of it. Dirt was one of the words she spat at them, and crooked was another. Burn. Split. Break. Ivy’s cap fell from her head, freeing her pale hair as she ducked and wheeled. The courier wanted to help her, but the other end of the station seemed miles away.

So she snatched up one of the watchers’ signal boxes and smashed it hard against the floor, freeing the pigeon within. The bird flew through an open window high in the station wall, out over the city toward Buckle’s watchtower. The moment the signal was spotted, more watchers would come.

The nameless saw, and they hesitated. For a moment, the station was silent except for Ivy’s ragged breaths.

Only then could the courier bring herself to run, but by then the nameless had scattered. Some rejoined the shadows while others fled through the doors and into the winding streets of the old town.

Their monster, spread too thin to sustain itself, struck out with a final convulsive lash before falling to shards. Ivy collapsed to the floor as ghosts rose to their feet all around them.

“Twelve ghosts, I heard,” one of the couriers at the next table said, and another, almost to himself as he sipped his tea: “I heard eighteen.”

But Ivy was shaking her head. “I met someone from calibration on my last run,” she said. “He told me they took twenty-six ghosts from Buckle Station that day.”

The others were silent. Twenty-six was more than anyone had guessed, more than anyone wanted to believe. The courier, seated alone at her table, turned and looked out the window.

Ivy leaned toward her across the aisle, yellow hair hanging to her chin. “I’m still amazed that you and I made it,” she said. “But then, the nameless didn’t go after you, did they?”

When the courier didn’t answer, Ivy turned back to her table. “They always recognize their own,” she said.

* * *

Beryl’s advice was simple. “Ignore them,” she said. “They push you around because they know they can’t beat you.”

Between assignments, when the courier wasn’t visiting Book or her ghost, she mostly kept to herself. When she did invite a woman or a man into her compartment, or to share her bunk, she rarely invited a fellow courier. Most of the time, she invited Beryl.

Beryl had big hands and a big laugh, and she liked to take her hair down the moment she came through the compartment door. She was a diviner, one of those who found new words for the couriers to deliver. Now Beryl lay sprawled over the courier’s mattress, bare feet up against the wall. For days afterward, the courier knew, she would find strands of red hair on her pillow and between her sheets. She didn’t mind.

“They push me around because I never took a name,” she said. “And because they think I’m Book’s favorite.”

“You’re my favorite,” Beryl said. “That’s more important.”

The couriers and the diviners had long maintained a rivalry that was not always friendly. The question, usually unasked but always in the air, was who did the real work of naming. The diviners, behind the locked doors of the divining car, employing secret arts to hunt new words and snare them with glyphs? Or the couriers, who traversed city, forest, and field, seeking those things—difficult to find because they were unnamed—to which the words might finally be bound?

But Beryl and the courier didn’t trouble themselves with any of that. The courier never boasted of her deliveries, and Beryl never complained the way the other diviners did when the headaches came, never sat in the eating car after divining a new word, sipping thin broth, eyes squinted against the faintest light.

Beryl divined names for machines and machine parts. She kept a pencil tucked behind one ear and her tobacco pipe in her shirtfront pocket. She had divined cylinder, counterweight, hydraulic, and weir. The courier was rarely assigned words that Beryl divined, but she knew that harrow had been one of hers, because they had talked about Juniper, the old farmer who built one in the shadow of those unnamed mountains.

Now the courier sat beside Beryl and took a deep breath. She wasn’t sure what it meant to be someone’s favorite.

“Tell me what you’re feeling,” Beryl said.

“There aren’t words for half the things I feel,” the courier said, and Beryl laughed.

Each new thing was a danger, a tool the nameless might use against the named, but Beryl was thrilled by them. She told the courier that when the names committee put the Number Twelve into service, no one really knew how the engine worked. Even now, parts of the engine were still unnamed. And because the Number Twelve had served as model for many of the machines built or rebuilt since—for other engines on the rails and for the churning giants that powered Hollow’s factories—the named were steaming along on the back of principles they barely understood.

“It’s part numbers and part guesswork, built with tools dug up from the other side of the Silence,” Beryl said. “It’s enough to make you think the world could end all over again.”

She spoke this way often enough that the courier was not wholly joking when she said, “You’d like that, wouldn’t you?”

“What I’d like,” Beryl said—and she finished the sentence by pulling the courier down onto the mattress with her.

Beryl’s skin was pale against the courier’s hands. The courier breathed in the scent of her, sharp and smoky, like naphtha and cedar burning together. Beryl turned the black curls of the courier’s hair on her fingers, searching her eyes, and the courier knew she was seeking a name, trying to claim her as the namers claimed each new thing. It pleased her, this attention, though they both understood that if she were named, she would cease to be what she was. This had grown into a game between them. Undressing on the narrow bunk, they played it without words: a search, a retreat, a surrender.

“You are a puzzle,” Beryl said into the courier’s ear, speaking the word as though it were the finest word they had. And when Beryl said it, the courier thought that maybe it was.

* * *

Alone, she puzzled things over. The body, too, was a machine they did not understand, housing parts, capacities, sensations for which they had no names. The named pretended not to know. The courier tried, too.

But sometimes, especially at night, and especially when the chief engineer got the furnace burning hot, she imagined she could hear a question in the engine’s roar, and feel an answer in the ache of her own body. Together, she and the engine made a music, soaring and strange, and she was afraid that everyone aboard the train could hear.

On the other side of the glass, cinders flew with the smoke, flashing orange before they vanished into the ditch beside the rails. She dreamed she was one of those cinders, streaking over the fields, never letting herself land, because if she landed she would burn the world.

* * *

She delivered tapestry. She delivered stoat and custom, outrage and shortcut. In Book’s office, she said, “You could just read my reports. It’s a lot of work to write them down.”

“It’s a lot of work to read them,” he said. “Indulge me. I’m an old man, and the sound of your voice is a comfort.”

So she indulged him with the story of shortcut, telling him of the narrow route, favored by the children of Leaf, that wound through alleyways and under balconies, connecting the center of town to the wooded gully where they liked to swim in summer and sled in winter. But she had only just begun speaking when the roar of an engine on the opposite tracks silenced her.

An army train. Behind the hulking locomotive came flatcar after flatcar, green and gray and black. The cars were freighted with war machines, their ghost-burning engines new from the factories, armor plates gleaming like the shells of beetles in the bright winter sun.

“So many,” the courier said.

“Are we at war again?” Book said. “I can never remember.” He was trying to sound bored but not quite succeeding.

The wars with the nameless had begun shortly after the rise of the sayers and the exile of the names committee. It was the courier Rain who had delivered war, then marched with the first soldiers into battle against the enemy, in the wilderness west of Whisper.

For a long time, the nameless had the upper hand. Monsters, bred in nightmares and seething with hatred for named things, poured over the borders to break walls and buildings and people. Only after the named learned to build and pilot war machines were they able to push the monsters back.

The courier counted three types of machine on the train. The biggest were the brutes, slouched like dozing bears, clawed hands resting in their laps. Only slightly smaller were the mantises, which the courier knew from the stories to be very fast, their forearms lined with jagged blades. Smallest were the lizards, sleek and nimble, serving mostly as scouts.

None of these machines were primed. That was the word the committee had delivered to describe the process that made a war machine operable. Each would have a monster burned in its furnace, to transfer something of its spirit into the machine. Only then, with a pilot trained to negotiate with the monster in its bones, could a war machine stand against the living monsters of the nameless. The process had been refined by her father when he worked for the army, years before she was born.

Lock had told her stories of the battles. Of machines roaring and coughing steam while launching explosive shells and belching flaming naphtha, fields and meadows lit by the burning of monsters the size of train cars. Some of the oldest machines still patrolled the borders and railways, but most had been decommissioned. The cost to keep them running was high. Once the machines were primed, only the ghosts of people, pure and unrefined, were potent enough to fire those great engines.

So instead of war machines, the named sent maps committee surveyors to chart the land. The couriers delivered names to hills, rivers, and meadows. The sayers spoke law and established settlements on the borders. The borders shifted outward, and with them the outposts of the wranglers, who trekked deeper into nameless territory to capture ghosts for the auction houses.

And hadn’t the borders been quiet for many years? Most of the monsters encountered by the named were sorry, ragged things—a shouted word would send them scampering into the shadows. Yet here were new machines, the train that bore them stretching on and on.

“Because of Buckle?” the courier asked.

“There have been other attacks,” Book said quietly. “Some among the sayers think the only way to stop them is with a show of force.”

She knew which sayers he meant. The one named Frost would be first among them. But Book didn’t like to talk about Frost, and neither did she.

“But where are they going?” she asked. “Who will they fight?”

Book looked uncomfortable. “There are reports—which I do not necessarily believe—that the maps committee is on the verge of a major discovery. Their scouts speak of a city. A city that stands at the edge of the world.”

“I don’t understand,” the courier said.

“I think you do,” Book said. “A city. And beyond the city, nothing at all. Nothing to be mapped. Nothing to be named.”

There had long been rumors—even before Book delivered rumor—of the last great city of the nameless. It appeared in a few old songs and stories, mostly those told by the Black Square Show or swapped by ghost wranglers and dreams committee hunters in their remote outposts and lodges.

“If the reports are mistaken, then why so many new machines?” she asked.

Without thinking, she had prompted Book to admit that the sayers could be wrong. But what the sayers said was law, and it was their law that bound the names committee to the train, that granted Book his power as committee chair. Who was he to speak against the sayers?

Still the cars of the army train swept past, the metal skin of war machines flashing in the sunlight.

“Maybe that’s enough for now,” Book said, closing the cover on her report. “Another one for the archives, yes?”

His voice was steady, but as he swiveled in his chair and drew the curtain closed, the courier could see that his hand was shaking.

* * *

She delivered melody. She delivered jumble. She delivered oxbow, and gibbous, and mustard, and sanguine.

“Sanguine,” Book said, savoring the excess. He took her by the waist and danced her around his office. “Let’s you and I be sanguine together.”

Before something fell from the something tree, there were words for everything, and if something new came along, anyone could find a word for it. No names committee, no diviners, no couriers. No ghosts either, some said, and others said that all the borders were more certain before, clear as lines on a map.

But those were just stories, and who could be sure? When something fell from the something tree, the old words went away, and most of the stories went with them.

This much the courier knew: some words were border words, and they did something more than name a thing. Only a few border words had been found, but each was a line drawn through the heart of the world, changing it forever. The first was word, divined and delivered by Hand long ago, so the named would know what to call the sounds that meant hand and fire, light and moon.

Years later, sleep was delivered by a namer named Drum, now remembered for little else. At first sleep hardly seemed to matter; the named saw almost no difference between what happened while they slept and what happened while they didn’t. Then, years later still, the courier Glove—on assignment and asleep—delivereddream. Only then did the named understand that sleep had been a border word: a border between us and the place the monsters came from. Some believed that if sleep and dream had been delivered before Moon delivered monster, then monsters would have remained always on the other side of sleep.

It was Book’s opinion that all the border words had been found, that none were left to divine and deliver. The courier knew he was wrong. In the corridors of the Number Twelve and in the streets of the named world, she listened for gaps and pauses, for a voice hesitating at the edge of something—something so big, no one knew it was there. She felt it in the air as an empty hole, dumb and hungry. She felt it when she heard new words, those bright jags of sound, rough and warm and strange. She felt it when she heard a word she had delivered—moth,brisk, calf,trouble—and the hair on her arms stood up. It was the word at the bottom of everything.

She delivered gossamer. She delivered burdock and snoop. She delivered switchback and glee, fluster and twine.

Some of those words might find their way into the naming songs, for children to sing at creche. But the courier wanted more. Someday, she would deliver a border word of her own. And only then—when she was old and tired, tired of everything she was—would she give herself a name and become something else, something for which she didn’t yet have a word.