6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

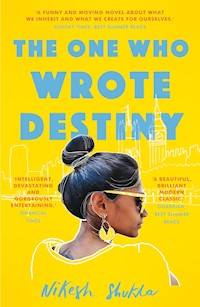

Evening Standard's Wander List Guide to 2019 Getaways Guardian's Best Summer Books, 2018 "A beautiful, brilliant modern classic." Sabrina Mahfouz, Guardian Neha has just been diagnosed with the same terminal cancer that killed her mother. Was this her destiny? She codes a computer program to find out, one that intricately maps out her entire life and the lives of those closest to her: her dad, who left Kenya for windblown northern England; her brother, a struggling comedian whose star is finally beginning to rise; her grandmother, who lost the man she loved to racist violence. By understanding the past, Neha hopes to come to terms with her present - and reckon with her family's and her country's future.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

THE ONEWHOWROTEDESTINY

THE ONEWHOWROTEDESTINY

NIKESH SHUKLA

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Nikesh Shukla, 2018

The moral right of Nikesh Shukla to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

P.335, reproduced with permission from Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London on behalf of The Beneficiaries of the Literary Estate of Henry Miller, copyright © Henry Miller, 1934

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is availablefrom the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 278 4EBook ISBN: 978 1 78649 279 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my sisters, kakis, masis, fais, mamis, faibas.For my kız kardeş. For Harrow ba, for otherhouse ba. For mum.

MUKESH

Keighley, 1966

What stories will they tell about me?

Or will I have to give people my own history?

Mukesh Jani

Stasis

I have no reason to be anywhere.

I find myself in an in-between world, with no purpose, except to lean with my back against the wall, across the road from Nisha’s amee and papa’s house. Not like a stalker, yaar. No, instead, I am posed like the poet I am, my pen poised to make ink marks and etchings on an open notebook page.

So far, all I have written is Nisha’s name: her first name, her full name, her first name with my surname, my first name with her surname, our names together. I write the openings of poems, but I never get past the first word of the first line. I have never written a poem before. I know that the first line starts with the word Nisha, though. Despite my lack of experience as a writer, her very existence inspires me, convinces me I was born to tell stories. Nisha means night. Maybe there is something in this for me to spin into poetry.

Nisha, tonight, you are . . .

Night.

I wear my best clothes because they’re all I have that isn’t my white pyjama lengha or my exercise shorts. And now that I’m not in school, I don’t need to subject myself to the level of humiliation that comes with wearing short shorts.

The damp breeze reminds me that I am alone in England, in a navy-blue suit jacket that used to belong to my father, which I cannot button up. Amee tried to find me blue trousers that matched it, but failed. In the grey of Keighley, the difference between the two is extremely noticeable. I have two white shirts which, due to the climate, I can wear all day every day as there is never any chance of getting hot enough to stain the collar. I look down at my father’s black tie, thin, with a pin that bears his name in Gujarati: Rakesh. I wonder what has happened to my wardrobe, now that I’m here. Amee has probably given everything to my younger brother. Because why take clothes invented for hotter climates to the wet and grey of England’s green and pleasant land? Neha, you were born here, but up until my teenage years, all I knew was Kenya.

Nisha, are you my destiny?

I scribble over this nonsense and stare at the half-empty page. I hope I seem deep in thought. Especially if Nisha is looking out of her window. The trick is to arrive twenty minutes before she is due home from school and stay until five minutes after she leaves for rehearsals for the big Diwali show. I practise my pensive face every morning in the mirror above the basin in my room. My thoughtful look, my deep-in-thought expression, initially looked constipated. It then went through a phase of looking as though I might have squirted lemon juice into my eye. Now I look blank. It is the best I can muster but I prefer it to looking as though I am in pain.

I glance at my watch again – my father’s watch; everything I own is my father’s. I have to preserve these heirlooms to pass on to my younger brother. Until then, I am the head of the family, and thus inherit all his fancy items.

The watch says 5.30 p.m.

On the nose.

The British have funny expressions for things. 5.30 p.m. on the nose. Everything has a nose, it seems. Everything has human features and human responses. They did not teach me this in school. I learned about verb conjugations, about vocabulary, about pronouns, adjectives, adverbs. I was never taught vernacular. Slang. The entire English language is composed of idioms. I feel lost most days when overhearing conversations at breakfast between the owners of the house where I lodge.

I never say anything.

They assume it is because I speak no English.

Actually, it is because I do not speak their version of English.

I hear keys in the door across the street and stare more intently than ever at my notebook. I want her to notice me and yet I do not wish to be seen. I can just about see Nisha in my periphery. Oh, Nisha, I write, changing my style, not having Nisha as the first word. Oh, Nisha, where is your head?

I frown. What does it mean?

Nisha closes her front door. I scribble over the line and try again.

Oh, Nisha, what are we going to do with you?

I cross this out. It sounds as though I am her dad.

Oh, Nisha, let me in.

I cross this one out too, as it borders on murderous.

Poetry is difficult.

The door opens again and I look up from my book. Nisha is struggling to balance a bag on her shoulder and a bundle of sarees under an arm. I look down again when I feel as though she’s spotted me.

Nisha steps out into the road and drops her keys. She bends down to pick them up. I don’t think she notices the bike coming along. Something overwhelms me and, fearing for her safety, I spring into the road, dropping my notebook and pen in my haste to get to her. I have to protect her. I have to save her. I have to stop her from getting hurt. I have to keep her out of harm’s way.

The bike crashes into my side and sends me smacking on to the cobbles of the street, my head banging against a jutting stone. I hear my name being called. I hear someone call me a bloody wog. I hear the click-click-click of a bicycle wheel in a free spin. Before things fade to black, I try to remember my happiest moment, just in case this is the end.

Amee’s aloo parathas could start wars. And they often did, between me and my brother. The trick to her aloo paratha was to slow-cook the potatoes all morning in water infused with ghee. That way, you could mash them with milk for a smoother texture. My younger brother and I fought over who got to have the first one, straight from the tawa.

I am sitting at Amee’s table. It is my last meal with her before I leave for England. Though I should feel jubilant, I am mournful. Naman and Amee have both privately scolded me for leaving them with each other. They hate each other so much. He’s at that difficult age where he’s old enough to be desperate for his freedom but young enough that he still needs her to cook and clean for him. She’s at the age where she would like some freedom from a teenage son who is old enough to cook and clean for himself, and responds to every request with an indignant groan like a cow being ushered from the middle of the road. They argue constantly.

I will not miss this.

I will not miss being the intermediary for two people who live in opposing camps. He wants freedom, fried foods, a football. She wants help around the house, a money earner, grades befitting a man of industry.

It’s tough being the clever one. The funny one. I do not complain, though. I’m also the quiet one.

According to Amee I was always destined to go and study in London. She knew that was always the plan. Before Papa died, after Papa died. Even in the brief moments when he was dying, we all knew this was the plan. Now that we are here, she is not so sure.

She dresses up her concerns with barbed comments about Sailesh, who is my reason for leaving. If Sailesh were not leaving, nor would I be. I did not want to go on my own. Because Sailesh is coming to do things other than study, she is concerned I will be distracted.

She is right, I will be.

If Sailesh is going to be working the Soho clubs, performing to rooms full of sheraabis, eating dinner with white people every night, meeting white girls, hanging out with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, am I really going to sit at home, quietly studying for my accountancy degree?

What Amee does not understand is that I can do both. I understand my responsibility: I just have to be twice as good as the other people studying to be accountants, so that I can have fun too. Why not? Why not have fun? Sailesh will be juggling for all these high-society people I’ve seen going in and out of the hotels in Mombasa, all wearing pearls and sparkling dresses or shirts starched whiter than an Englishman holding a milk bottle in winter.

Amee must know this, that as soon as I am in London I plan to have fun, to drink and party and meet girls and not study, which is why she puts the first aloo paratha, straight off the tawa, on to Naman’s plate.

He is so surprised, he looks from his plate up to me and then back down again.

Amee drips ghee on to the paratha.

I look at her. She is avoiding eye contact with me.

‘Bhai, would you like half?’ Naman asks.

Those five minutes that follow – with Naman and me sharing the aloo paratha the way brothers should, while my mother is too stunned by his moment of generosity to protest – that stillness, when all you can hear is the churn of chewing, that is the happiest I have been in a long time. Certainly since Papa died. Who can remember what life was like before he passed?

I can hear my name bouncing around in my eardrums.

‘Mukesh, Mukesh,’ I hear, in Nisha’s voice.

My half-conscious brain translates the tone of her voice as one of affection and concern, but as I open my eyes to the blindingly bright white clouds, I can see that she’s angry and impatient.

‘I’m late, Mukesh. You okay? Tell me you’re okay. Not today of all days, bhai. Not today.’

I open my eyes, pat my hands up and down my body, feeling myself, just to make sure I’m still intact. She is frowning at me. Her face is partially obscured by curls, but she is definitely frowning.

‘I’m awake, I’m awake,’ I say and sit up, as quickly as I can.

I have never spoken to her before. She knows my name. How does she know my name?

She offers me a hand, to pull me up. I hesitate, but she jabs it at me insistently. I take it. Her hand is dry. Lukewarm. I pull on it, but I’m too heavy and overbalance her. She lands heavily next to me, swearing in English. She scowls at me, swears again and then begins gathering the fabrics she has dropped. I try to help but she yanks them from my grasp.

‘What are you doing? I’m late,’ she says.

Announcing his presence, the man who crashed into me straddles his bike and starts cycling away, shaking his head, muttering about bloody wogs.

I call ‘sorry’ after him.

He continues to shake his head as he cycles away down the middle of the road.

‘Why are you apologizing to him?’ Nisha asks angrily. ‘He called you a wog.’

I haven’t spoken to anyone since my first day in Keighley a fortnight ago. Not since my landlords asked me if I had any questions after they had shown me around my room and the facilities. I said no, added a thank-you as an afterthought and sat on my bed, watching them both go into their bedroom across the hallway. I heard the door lock, and when I heard them in hushed urgent tones discussing their impressions of me – harmless, teeth, smell, were the words I caught – I closed the door and continued to sit on the bed, hoping for some inspiration.

How did I end up here, 213 miles away from London? I hope Sailesh hurries up, I thought. This is not where I was supposed to be.

I didn’t speak to anyone during my first week – not Nisha when I noticed I lived a street away from other Gujaratis, nor her brother nor her parents, not the people I bought eggs from, which I wasn’t allowed to cook until I provided my own pans, according to Mrs Simpson, my landlady. (She was worried about the smell of curry seeping into her own pans. Did she think I ate fried eggs with curry?) I didn’t speak to people I passed in the street, sat next to on benches, made eye contact with. I learned that I could be introverted when regarded as an alien by all who came across me. So I kept quiet.

In the evenings, I whispered certain words to myself that I had overheard during the day, to keep my English up to date. I whispered things like cummingwiv, outen, rutching, erwile, dook into my pillow, hoping that the more I repeated them, the more they would make sense to me, start to trickle off my tongue with ease. Down in London, when I eventually get there, I will talk like the locals, charm like the locals, make love like the locals.

‘Hello?’ Nisha is still looking at me. Her face is beginning to register concern.

I smile dumbly in response, showing all my teeth, nodding my head a little.

‘Why are you saying sorry to that man? He ran into you. He called you a wog.’

‘Sorry,’ I say to Nisha.

I’m mesmerized by the way her nose twitches when she talks. I have not seen her speak before. I’ve not seen her lips move with such careful deliberation to avoid an accent. I have not appreciated how low her voice is, as though she is humming into the wide mouth of a foghorn.

‘What is a wog?’

‘Are you stupid?’ she asks.

Nisha, my love, the object of my nightly fantasies and daily morning hygiene rituals, your talking voice is sending me into paroxysms of shivering explosions all over my body.

‘Stupid, like dropped on your head as a child?’ she continues.

I think I love her even more now that she is speaking to me.

‘I got in his way,’ I say.

‘You were crossing the road. He should have been looking where he was going. Fut-a-fut he was cycling. He didn’t see you. Or he did it on purpose. You never know with these English.’

‘How do you know my name?’ I reply, thrilled by the idea that she knows who I am. She knows exactly who I am.

‘You’re desi – we all know each other round here. And Mrs Simpson asked my mum if we were related to you. She pronounced it Mooooo-cash. Like she wanted money for a cow.’

She laughs. Her face changes. She has a smile that erupts from her chin, upwards, like a volcano of positivity. She has a serious face when she is thinking and a serious face when she is walking – I’ve noticed this in my various observations from afar. But this smile, it is utterly beguiling.

Oh, Nisha, you make me want to believe in destiny.

‘I guess there aren’t many of us here,’ I reply.

‘How did you end up in Keighley?’ she asks, starting to walk, turning her head back so that I can answer her.

I assume she wants me to follow her. So I do. And because I haven’t spoken to anyone in two weeks, and because it feels unnatural communicating, especially in the tongue I have been suppressing since I arrived, I tell her everything, much more than she needs to know, every excruciating detail. And bless her, Neha, you wouldn’t believe it, but your mother listens to me. Or, at least, she nods her head every now and then as if she’s paying attention.

‘My best friend Sailesh, he’s a juggler, one of the most famous jugglers in Mombasa. He has been playing the hotels for a few years now. His papa and my papa were best friends. But his papa died, you see. At the same time as my papa. It was a freak accident. They both drowned at the same time. No one saw it coming. They were trying to save my younger brother, Naman. And they swam out to get him. And they both . . . well, that’s not the question you asked. My brother’s fine, in case you are wondering. But my dad and Sailesh’s dad died. And Sailesh threw himself into juggling, obsessively. At first no one noticed how talented he was, because – you know how it is. We all look the same. Especially to the British expats and holidaymakers. Eventually Sailesh became so well-known he was offered work in the clubs over here. “Come and see the mysteries of the dark country.” He said yes because we’ve both watched movies. We know that this is the home of James Bond. Sailesh had to wait for his work visa to come through. He convinced me to come with him. I had always wanted to come to Great Britain to study. My papa had saved for years for me to study. And I applied to a college. In London. Sailesh’s work visa didn’t come through in time so he suggested I go on ahead and find a place for us both to stay. And he would arrive and pay for the rent and I could start studying. He told me that Keighley is a place near London that has lodgings accepting coloureds. He knows people who live here. So I came here. Here I am. In Keighley.’

Nisha stops walking and turns round to face me. She looks at my face, trying to read it, understand what is going through my brain. Then her lip quivers before that smile volcanoes upwards across the entirety of her face. She has a gap in her front two teeth that becomes more pronounced the closer it gets to the gum.

She giggles with the whole of her body.

I smile with her, not sure where the hilarity lies, waiting for her to fill me in on the joke.

‘What’s funny?’ I ask about twenty steps later, stopping in front of a house and folding my arms.

She looks at me.

‘Have you gone mad? Keighley is two hundred miles from London. What are you doing here? You can’t get from here to college and back in a day.’

‘I know,’ I tell her.

I don’t know how it happened other than that I got sucked in by Sailesh’s enthusiasm.

Go to Keighley, he said. They take coloureds there. You will only be there a few weeks, a month, three maximum and then I will come and get you. And we will tear London apart looking for Tom Jones and Engelbert Humperdinck. Keighley is not that far. Your school does not start for three weeks after you arrive. You can wait for me. You have money, yes?

I said yes. It was the easiest thing to do. Arguing with this man is impossible. He talks like a machine gun. He will unleash a hail of words at you until you end up with your hands over your head, begging for mercy. Machine guns, they are bad for your health, bad for friendships.

I wish I had listened to my instincts and trusted my map-reading skills. England may fit inside Kenya four or five times, but even with that proportionally restricted map in mind, Keighley and London are far apart when you are in a strange country, on a limited budget, with no friends, family, job or idea of what to do by yourself.

This is the longest time I have been on my own.

I thought I would find myself in this month. Discover a love of novels or learn to play an instrument or write letters to my loved ones. And Sailesh. And Naman. Amee, I could have written to Amee.

Instead, I got distracted when I saw Nisha for the very first time. She was walking down my street, laughing with a friend, her hair shaking like palm trees from side to side, while I stood at my bedroom window, airing out my armpits after a hot night, tossing and turning and cursing the English for having central heating turned on all year round.

Nisha is the third person I have developed feelings for.

The first was my maths teacher. He seemed so cool, yaar. He was always singing the best songs, wearing the shiniest shoes and wore sunglasses at all times except when he was in class. I used to linger after every lesson, or turn up early hoping to spend extra time with him, hoping to get some bon mots, advice or recommendations on how to be so unbelievably cool in life.

The second was a girl called Sri, who I went to school with.

And now Nisha. Who I have been wanting to notice me for two weeks. And all I had to do was throw myself in front of a bicycle, trying to rescue her when she didn’t need rescuing.

‘So that’s why I’m here,’ I finish. ‘Because my friend told me to come here. Because the British would welcome me until he arrived.’

‘You know what else is funny?’ she asks. ‘I know Sailesh. Shah, na? Sailesh Shah?’

‘Yes,’ I say, rubbing at my chin and scratching my ear. ‘How did you know his name?‘

Nisha laughs. ‘He is my cousin. No wonder he sent you here. It’s probably the only place in the UK he knows. I didn’t know he was moving here.’

I nod.

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘He’s quite talented. Don’t you think?’

‘I have never met him,’ she says. ‘He’s just a cousin I write to and send a rakhri once a year.’

I nod again. My responses are slow. I can’t think of a thing to say to her. I feel as though every English word I’ve ever learned is useless because I cannot connect them together into a sentence. I’ve never spoken to a girl before. Even at school, I kept myself to myself. I let Sailesh have the relationships. I had the headspace. Sailesh could talk to anyone in any capacity. I was his mute sidekick.

I realize we are in a part of town I don’t recognize. We have left Nisha’s street and are approaching the church that dings a bell on the hour every hour, without fail. It wakes me up most nights. I’m constantly aware of the time, how slowly it is moving, how much I feel as if I’m in suspended animation.

‘Where are we going?’ I ask.

‘Where are you going?’ she replies. ‘Good question, yaar. I don’t know.’

‘I think I’m following you to where you’re heading. I don’t know where that is. I’m sorry. I will go home.’

She exaggeratedly rolls her eyes, but then smiles at me.

‘Will you come to our Diwali show tonight?’ she asks.

‘It’s Diwali?’ I ask, playing the innocent.

‘Yes, bhai. It’s November. We are putting on a show in the community hall. You were going to come to this, yes?’

‘I didn’t know it was happening,’ I tell her, my body tense with an excitement I’ve not felt since leaving Kenya.

‘Yes, bhai. Tonight. Seven p.m. People are coming from Bradford, from Huddersfield, to see our show. Did you not know about it?’

‘You are the first person I have spoken to in two weeks,’ I tell Nisha.

She laughs.

‘I do not believe you, Mukesh. You know what I think?’

‘What?’

‘I think you want to be in the show. That’s why you’ve been waiting outside my house for a week. You know I am organizing it.’

I stammer a protest. She has seen me. I thought I was invisible. I thought I faded into the white wall I’ve spent the week leaning against.

‘It’s fine, Mukesh. We can find a job for you. Maybe you can be the deer that Laxman kills? Or Hanuman’s gada. We could wrap you in gold fabric and you could make a clank-clank-clank noise when Hanuman wields you. Yes, the way you defeated that bicycle, you can be the gada.’

Somewhere in me a ticking starts, a countdown timer to panic.

Nisha looks at me and laughs again, this time bending over, her hands on her knees.

‘I’m joking, yaar. We can’t make you be a gada,’ she says. She pauses for dramatic effect. ‘You don’t have the body type.’

‘Oh, okay,’ I say, a little disappointed.

‘Do you want to be involved?’ she asks me. ‘We need to finish sewing the backdrop together, someone to do all the make-up, someone to play tabla. All by tonight. It’s a disaster this show, I tell you. A disaster. Anyway. What are your skills?’

‘I am a poet and an actor,’ I lie.

Trigger

Somewhere, somewhere, Nisha, my heart is in a box

A box locked with your hair locks

I listen to the roll and I listen to the rock

You are the hole in my sock.

My brain clouds.

‘What do you know about the Ramayana?’ Nisha asks me as she opens the gate leading to the back door of the hall behind the Catholic church.

I can hear the drone of a harmonium making its long elephant trumpet of desperation. The person playing it is clearly not an expert. A beginner at best.

‘I read the comics of it back in Kenya,’ I say.

‘We are doing a performance where Sita dances for Rama, just before they return to Ayodhya. To show him everything she has gone through. Everything she has learned. Do you know it?’

‘No,’ I reply, then immediately regret it. I must say yes to everything. Ignorance does not make you needed. Knowledge does.

‘I made it up,’ Nisha says, smiling. She closes the gate behind me. I can hear the thump and pat of bare feet on parquet flooring. ‘It is not actually in the Ramayana. But we only have girls in our community. And my brother. And Prash, but he’s a bevakoof. So we had to come up with something. Have you met my brother? Chumchee? His name is really Chetan, but we call him Chumchee as he is always hanging around.’

‘Yes,’ I say.

‘Oh, you have? Perfect, yaar. I am so glad I spoke to you. He will be less nervous having another boy dancing next to him. Are you happy to be Rama? He refuses to be him, yaar. We promised him he can be Laxman. Not Rama. You have to be Rama. If you do not do it, we will have to ask Suresh uncle. No one wants to ask Suresh uncle anything. You know about Suresh uncle?’

‘Yes,’ I say.

This is proving an effective strategy.

‘Oh God, has he ever told you any of his stories?’

‘Yes,’ I say.

‘Which one?’

I shrug my shoulders and smile awkwardly as if to say, yep, that one. Nisha frowns as she opens the door.

We walk into the school hall.

I expect to be transported to Dandaka Forest. Instead I am taken back to my childhood days. Benches that you had to sit on for assemblies if you were in the top year. Everyone else sat on the floor. Getting to the age where you were on a bench was an honour to look forward to, till you realized it gave you splinters on the backs of your bare legs. Bench privileges did not mean trouser privileges as well.

The walls are bare and once were white, but now they’re scarred by decades of bored children picking off the paint, using it as target practice for flicked goongas, spraying it with shaken cans of soft drinks.

There are six people in the room. There is Chumchee. He is short and waddles like a penguin. He is pale and vacant, the type who would smile at clouds and old ladies. He looks like someone who cannot stop sweating. He smiles at the floor when we walk in.

There are three girls, dancing in a line, all dressed in sarees and wearing cat-like eyeliner, because each one wants to look like Mumtaz. They look like children playing dress-up with their mummy’s saree box.

There is an old balding man in an off-white shirt and black trousers. He sports a sequinned waistcoat from a jubo lengha suit. He sits in the lotus position, murdering the air with a single-note drone from his harmonium.

There is also a white man armed with a butter knife, scraping off chewing gum from the bottoms of chairs. He looks harassed, as though he should be somewhere else. And he should. What a job.

‘We have found our Rama,’ Nisha announces.

Suddenly, I realize the enormity of the situation. Especially when Chumchee stands up to clap at me.

The girls stop dancing, put their hands on their hips in synchronized aggression and look at me, expressionless. As if they are waiting for me to say something impressive.

I wave.

‘I am playing Rama,’ I say.

This is an important role, playing one of the incarnations of Vishnu, and I feel like a trespasser in someone else’s community. I am to stand up, in front of other people’s families, and parade myself for their judgement. Mothers and fathers will be assessing me as a potential son-in-law. They will want to know what I am studying, who my grandparents are and what side of the heart disease/diabetes spectrum I fall into.

Both, as it happens. My family likes to have all angles covered.

‘Him? He is playing Rama?’ one of the girls asks suspiciously.

Nisha turns questioningly to me. She smiles. It is a smile that could launch a thousand ships. Which is a strange comparison to make. I know about Paris and the Greeks, but I still do not know why anyone would launch a thousand ships after a girl. We now have commercial aeroplanes.

She is beautiful. My hips ache. My toes burn. My mind turns from cloudy to fizzy.

‘Yes,’ I say, looking at her.

Chumchee appears by my side.

‘Brother,’ he says, smiling. ‘My brother.’

I offer my hand for him to shake but he looks at it as though he would rather not be touched. Reluctantly he offers me fingers, which I pull on once. In the years I knew him after, I learned that it wasn’t just me. Year after year, I saw him shrink when people approached, and stand two feet away from conversations, always listening, never part of the action.

He smiles, stepping back from me as quickly as possible, stumbling into some chairs.

Nisha, oh, Nisha, I would follow you anywhere.

She tosses something to me. It is a dhoti, green with pink sequins sewn into a makeshift paisley. It looks . . . big.

Chumchee hands me a domed crown, like the mound of a temple. It’s gold foil over a safari hat.

I hold both the dhoti and the crown and I look around the hall. The harmonium player has stopped playing his long endless note and everyone in the room is looking at me, smiling expectantly. The man removing chewing gum has disappeared. All eyes, however, are on me. I am here to save them all. I have to be their Rama.

‘Get changed then,’ Nisha says.

‘Yes, bhai,’ one of the younger girls says. ‘We have to teach you your moves. We open the doors in four hours.’

I drop the crown.

‘Four hours?’ I gulp.

What do you mean four hours? I have just arrived. I have never been in a theatre production. I cannot dance. I don’t know what anyone is doing. I don’t know what I am doing.

‘Mukesh bhai, are you sure you want to participate in this?’ Nisha asks quietly, walking towards me, her hand outstretched to put reassuringly on my arm.

I wait for her touch. I will melt into it.

I edge forward, so that my sleeve reaches her fingertips that much sooner.

‘Bhai saab,’ she says. ‘We need you to get changed. So we can teach you the dance moves and show you what you need to do. Where to stand. How to act. Who to look at. Yes? Is this okay? Can you do this?’

I take a deep breath.

‘Yes,’ I say.

This is not going well.

I was a quiet kid. I did not like anybody looking at me and sat in the classroom in the middle. Away from the clever boys at the front, away from the naughty boys at the back, away from the boys on the sides making hungama. The teacher never picked on anyone lost in the middle to answer a question. I would know the answers sometimes, but saying it out loud filled my heart with terror.

Talking in public was my greatest fear.

I grew up between a dust bowl and a blue sea. Where they met was an island, a booming port town called Mombasa. We lived there at an unremarkable time.

I do not believe in destiny. Not for our family. I do not believe in learning from the past. We live a life and then we die. I do not think there is anything remarkable about history. You know that, don’t you, Neha? You are aware that whatever we learn about the past doesn’t shape the future. We don’t exist in loops of time. Nothing repeats, except human nature. Not events. Not mistakes. We’re not pre-programmed to be dictated to by our past. All we can glean from it is that at some time at some point in some distant bygone era, someone will have done something to surprise you now.

None of this is by design. It is by circumstance.

My papa had the same routine every day. He and Amee rose at 5 a.m. for their yoga routine. This woke the rest of the house because they did sun salutations before clearing their nasal passages, one nostril at a time. This ak-ak-ak-akkkk noise signalled to the children that it was time to get up. Once yoga was over with and while breakfast was being prepared for my father, he did his calisthenics. He took a steel tray and balanced it on his head whilst doing hip rolls and knee bends. He stood on his head for a full minute and only then would he come to the kitchen for his garam chai and two sugar rotlis. Then, it was work – and work, for him, had to be hassle-free. He had spent most of his life in the family haulage business in Nairobi, staring at ledgers and signing cheques and having lunch with the bank manager every week. It was a clockwork existence, and he wanted to be free from such regularity. So he left the trucks to his brothers and moved to the coast to have me and Naman. And a hassle-free job. He opened a kiosk. He sold cigarettes to white men and newspapers to everyone else.

But he still had an accountant’s respect for numbers. He told me how his father had told him why it was important he understood them.

‘I want you to understand every process, every minor detail of every number, son,’ my grandfather had said to Papa. ‘Then nobody can take you for a ride.’

‘I understand, Papa.’

‘Numbers are life,’ my grandfather had continued. ‘You understand that. Without them, we cannot survive. They create patterns in life. We exist in patterns. Without them, life is chaos.’

‘I understand, Papa.’

As for me, the teachers told Amee and Papa, every time we had our school reports, He has not made an impression in class. His written work is good. But he does not speak. And his maths is terrible.

‘Why do you refuse to speak in class?’ Papa asked me.

‘I do not need to prove to the class that I know the answers. I prove it to the teacher.’

He seemed unconvinced.

My father told me, ‘You must never assume people know what you are talking about. You must never assume they even know you are alive.’

*

I ask where the changing rooms are.

Nisha smiles sheepishly.

‘This is the whole room. Here. You can change on the stage and we can all turn away. Yaar, the thing is, we are going to see it all anyway, bhaiya.’

Chumchee laughs.

‘I might look,’ he says. ‘We are brothers, after all.’

I don’t want Nisha to see my frustration with the situation I have agreed to. I want her to think I am cool and breezy. Like Jimi Hendrix, man. That kind of thing. I want her to think, look at this guy. He strides into my life, hurling himself in front of a bicycle to protect me, and now he is saving my play at the last minute by playing the hero, because my bevakoof brother is being difficult – so I should definitely kiss him and cuddle him and promise him that, for ever and ever more, I will be his, whatever he wants me to be.

My girlfriend, I think. I want you as my girlfriend.

Oh, Nisha, Nisha, I unbutton my shirt.

Nisha, seeing I am doing her bidding, turns back to her dancers.

‘Anjali,’ she says wearily. ‘You are not in time.’

‘Come on, Nisha. It’s a lot to learn. We only started this morning.’

I pause. This morning? Nisha, baby, darling, your organizational skills leave a little to be desired. I take off my shirt.

I stand topless, my hands planted on my hips, my shirt bunched in my fist. I am in hero stance.

No one pays any attention. Except Chumchee. He hovers in front of me, mirroring my pose. The little suction cups of my breasts tingle in the cool air. My nipples harden. I wish I had started from the shoes and socks and worked upwards. Disappointed in the lack of response, I start unlacing my shoes.

I hate being barefoot. Especially in places my toes are unfamiliar with. The ground feels crusty and unknown. My foot feels untrusting. I rock back on my heels, lifting my toes, keeping the surface area of foot-to-ground to a minimum.

I unbuckle my belt, watching Nisha instruct the girls, who peep at the wispy upside-down triangle of hair on my chest instead of following the choreographed steps. The harmonium player oozes out a melody, a slow droning piece, centred around three notes.

I start to pull my trousers down before I stop and realize.

I am not wearing underpants.

They are, the three pairs of them that I own, bathing in the basin in my room, waiting for me to beat the water out of them until they are dry.

I stop undressing and begin to edge into the corner.

One of the girls, seeing the bare curve of my bottom as I pull the trousers back up, sniggers. Nisha calls a halt to their rehearsal.

‘What’s the problem?’

Anjali points. She turns around.

I shuffle backwards in a panic but manage to stand on the hem of my trousers, tripping myself up and falling to the floor, bare bottom first.

‘No, no!’ I cry, protecting my modesty with my hands.

The girls burst out laughing. Nisha buries her eyes in a hand, her entire body shuddering with silent laughter.

Chumchee leaps to my defence, waddling over and attempting to help me shield my crotch. I try to bat his hands away but he is firm in his efforts and surprisingly strong.

I look at Nisha, openly laughing now, as if this is not the first time someone has exposed themselves to her.

I rue the day I decided to say yes to everything.

When the girls return, ten minutes later, smelling of tobacco and factory smoke, I have composed myself and changed into my outfit.

I wear the green sequin-and-paisley dhoti.

Again, I stand with my hands on my hips, my back ramrod straight, because if I move my head the crown will slip off.

I am formally introduced to the dancers – Anjali, Shilpa and Mala. I shake their hands and none of us makes any reference to what happened ten minutes ago.

I never remember the okay things. Only the good things and the bad things. They are what form me, what propel me through life. Surely, it is the okay, the mundane, the everyday that makes me more than the good and the bad times. When I first arrived in England, I was nervous, anxious all the time, panicking, because Sailesh was not here. He chose my path for me at all times. He knew our best move as a team. This was our dynamic. He would decide what was next for us and I would emphatically agree.

I haven’t seen him for two weeks. I miss him. I have only my memories of our happiest times. I think about this a lot. Those happy times made me who I am. And yes, Neha, you will never know Sailesh. He made me into the person I was.

Without him, I would not have met your mother.

When he started becoming famous at the hotels, it didn’t change him. I was worried he would leave me behind for a more exciting life but he remained my best friend. His dad was disappointed that he was straying from the family business. But, see? We had an end-game. Our ultimate goal was to head to Nairobi.

In the big city, we could be who we wanted to be. I had a cousin – Manish – who lived there, working in the family’s maize business. He used to write me letters about what Nairobi was like. He told me about the girls, the music, the clothes and the freedom in general. Despite living in our family’s compound, he said, there was a freedom in having access to the city. We were seduced. We wanted what he had.

Sailesh’s career at the Casablanca hotel was entirely ruled by the assumption that one day we would move on to a bigger city. Nairobi. London. Certainly not Keighley, 213 miles north of London, the nearest place that advertised friendly lodgings for coloured workers.

I went a couple of times to watch Sailesh juggle. He would sneak me in through the kitchens and I would watch him stand in the centre of the room, an Indian, surrounded by the British Empire. This is something you cannot appreciate – I grew up while history was being made, during an occupation. I watched Independence unfurl before my eyes. I witnessed the last days of the British Empire. All these white men, eating and drinking as though they were destined to own us for ever. All those men, with their furry white chests and moustaches, their hats and their beige clothes, their young girlfriends and their strait-laced wives, all of it coming to an end. Man, it was a scene.

Anyway, I would stand in the door of the kitchen and watch the routines. Sailesh’s look of concentration was a smile with a tongue in the left cheek. He wore one of Papa’s old suits which had been discarded because of a tear in the left shoulder and wear in the crotch from overuse. Papa cast off the suit but Amee was resourceful and knew how to tailor it into something wearable. She re-sewed the crotch and worked the sleeves into something deliberately torn, to make Sailesh look like a dishevelled juggler. It was part of the act. He walked on stage – well, the centre of the room – playing a drunk hobo, with an empty bottle of beer. He pretended to trip, threw the bottle of beer into the air and as it reached the peak of its arc, he would remove another from his pocket, try to sip it, realize it was empty and then throw that into the air as well. He would juggle the two. Then a nearby waiter would walk past him with a tray carrying two bottles of beer; he would grab one, down the contents and fling it up to give him three bottles in the air. The third was a plant. It was half-filled with water. He juggled the three bottles, stumbling about like a drunk. People applauded. This was just his first routine, one that he savoured because it offered the maximum showmanship for minimum skill. It required no concentration – even though each bottle was weighted ever so slightly differently, muscle memory allowed him to throw them up with the precision of a master.

Things happened quickly after those first few performances. He was given a regular job at the hotel and left school to pursue the juggling. His father was terrified that Sailesh would never amount to anything. There was a quiet rule in his family: a chance is only a piece of chance; hard work is worth more than chances. It doesn’t make sense but his father liked to think of himself as a philosopher. He wrote these motivational messages on the board outside Cheap Ration Store. Many times people would mistake his shop for a church.

Sailesh was granted an opportunity to come to London and work. He was contracted by the owners of the Casablanca hotel, who had interests in London, to play cabarets in Soho for a trial of one month, if successful extended to six months and then potentially permanently.

We had had dreams of Nairobi for so long that London seemed like a walrus; we knew what it looked like in books but assumed we would never see one in our lifetimes. Nairobi for us was a lion, a once-in-a-blue-moon sighting from the window of a car.

Sailesh was excited. This surpassed any expectation he had for his life, which had already been overtaken by his small success at juggling. We were expected to walk in our fathers’ footsteps, to go and work in their businesses, continue their success, and survive to pass on even more to a future generation. We were not meant to live our own lives. Our desire to escape was real.

We wanted something more than what was on offer. Mainly because our letters from Manish showed what else was out there in the world, what life there was to be lived. It wasn’t just the thought of girls, or the thought of drinking or anything like that. There was just this feeling that in Nairobi we would be free to explore our options. Maybe through the arts or through other people’s businesses. It felt freer than where we were.

Nairobi, that’s where I always thought we would end up. But with no tangible plans to go, other than the general desire to escape, I started to feel as though I would live out my days running my father’s kiosk and fighting with Naman over parathas. So when Sailesh told me about the London contract, he asked if I would come.

I said, of course, bevakoof.

When he broached the subject with his amee and I with mine, I had more success. This was because I presented it as a chance for further education. When I told my amee that Sailesh was heading to the UK to work and that I could go with him, maybe to study, maybe at a university, she practically exploded with happiness. She told me that before he died Papa had saved a special fund of money to give to either Naman or me should we want to continue our education. I would need to work to pay my rent, the caveat was, according to Amee, but I would be the first Jani boy to go to a university. A real university with professors and lectures and learning to better one’s self. My father had wanted to get a degree in accountancy but instead had had to work for the family business. And that job, the stress of working with his brothers, nearly killed him. So he moved to Mombasa. Which did kill him. Because who lives by the coast but cannot swim properly?

Sailesh, on the other hand, broke his father’s heart. We were two months away from finishing school and Sailesh’s papa wanted to start taking it easy, while his son assumed more responsibility at the shop. Sailesh was unsure whether his father would let him go. But then the tide intervened and took our fathers from us.

This is why I do not believe in destiny, my child. Destiny has one single agenda: to force you to make decisions. Had Papa lived, Neha, you and I would be speaking in Swahili right now. Not this terrible English. Papa made a choice to run into the sea to rescue Naman. I made a choice to leave Kenya. I am not trapped by destiny. I command my choices.

I had to find something to study and I wanted it to be poetry. I liked poems. I liked reading them and the idea of writing them. Especially the rhyming ones. But I didn’t think my father’s money would be paid out for me to learn to write poetry. Naman was also encouraging me to go, saying, brother, you have to go and you have to get set up so you can bring me over. I want to walk through Leicester Square.

So I told Amee I would go to London to do my A levels and then I could pursue an accountancy degree. This made her so happy. She paid the money for my ticket – one way because, she said, when I was done I would be able to pay my own way to come back and visit.

Nisha leads me into the centre of the stage.

‘Stand still,’ she says. ‘With your hands on your hips. Look like a hero.’

She counts in – ek, bey, thrun, char – and the harmonium blasts out a slow trance-like melody. The girls dance behind me. I can feel their shuffling steps, hear the jangle of the bells around their ankles.

I am bewitched by Nisha, playing Sita, my wife.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)