0,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: J. R. Mathis

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

My wife died in my arms, the victim of a nameless killer's bullet. I should have died with her. But God had other plans for me.

Fifteen years later, I'm back where it all happened. I just want to forget, but the past won't leave me alone.

Now, I'm asking a woman who I left broken-hearted twenty years before to catch my wife's killer.

I'm Father Tom Greer, a Catholic priest, and I'm playing with fire.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

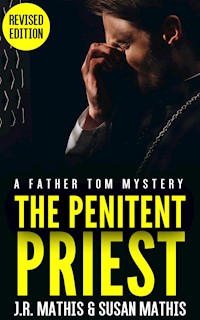

The Penitent Priest

The Father Tom Mysteries, Volume 1

J. R. Mathis

Published by J. R. Mathis, 2020.

The Penitent Priest

Copyright © 2020 by J. R. Mathis

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

For information contact :

J.R. Mathis

http://www.jrmathismysteries.com

Book and Cover design by J. R. Mathis

Cover Photo Adobe Stock Photos

Book Formatting by Derek Murphy @Creativindie

First Edition: June 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

The Penitent Priest (The Father Tom Mysteries, #1)

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Epilogue

For Susan

––––––––

SIGN UP FOR THE

MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

TO RECEIVE SPECIAL OFFERS, GIVEAWAYS, DISCOUNTS, BONUS CONTENT, UPDATES FROM THE AUTHOR, INFO ON NEW RELEASES AND OTHER GREAT READS:

WWW.JRMATHISMYSTERIES.COM

One

I hadn’t been at Saint Clare’s Parish since my wife’s funeral.

Now I was standing before the altar about to pour holy water over the forehead of the squirming infant in the arms of his proud mother. We got to the part I had been nervous about. I carefully took little Benedict James from his mother’s arms and held him over the font. I picked up the silver shell, dipped it in the water, and poured the water over his head. The little boy was still and peaceful, looking at me with wide-eyed wonderment. I had worried for days that he'd scream the entire time, and prayed that he wouldn’t. Fortunately, this one time, my prayers were answered.

I handed Benedict back to his mother, breathed a sigh of relief and turned to the assembly.

“Let us welcome Benedict James Reynolds into God’s family.”

The crowd applauded, punctuated by the cries and screams of the dozens of children in the pews.

The 10:30 a.m. Mass was a lively, well-attended one. From what I could tell, the church was almost to capacity. The pews were filled with young families, but all ages were represented. The earlier Mass was older, quieter, and not half as full. I recognized some of the people from years ago. Anna Luckgold, my mother-in-law, was there, third row from the front. Glenda Whitemill, the parish secretary, sat in the front row studying my every move.

She had also been at the 8:00 a.m Mass.

I made it through my first mass with more than an audience of five since—well, ever. Everything was fine until the end. I had just finished the prayers before communion when I saw movement out of the corner of my eye. Glenda Whitemill had left her seat and moved to the altar with the other Eucharistic Ministers.

Instead of lining up with everyone else, Glenda came right to my elbow and whispered, “Remind the parents to keep their children in the pews.”

“What?”

“They only come up if they’re old enough to receive communion. Otherwise they have to stay put.”

I looked at her and shook my head slightly. “I’m not going to do that. The parents can bring their children up for a blessing.”

“But Father Anthony—”

“Is not here,” I said, firmly. “Now please go back with the others.”

She looked at me, her eyes burning with indignation.

“Yes, Father,” she said quietly. She walked back and stood with the others.

After that, everything went smoothly. After the final prayers I said, “Please be seated for just a moment.” The congregation sat down, mothers and fathers wrestling reluctant toddlers and older children back into their seats.

“Before the final blessing,” I said, “I just want to say how happy I am to be here at Saint Clare’s. I look forward to the next four months with you, and I want to say that my door is always open if you have a need or concern. I’ll do my best, but I’m not planning on making any major changes, since I’ve never been in a parish on my own before, so please bear with me as I find my way.”

I heard a wave of murmurs through the church, intermingled by the fussy children. I tried to read people’s faces, I thought they looked approving—except, of course, for Glenda Whitemill.

I let the murmuring die down. “Most of you are newer to the parish.” I paused before going on. “Some of you may remember me from—from my previous life.” I saw Glenda jerk her head up at that. I heard more murmuring and thought I noticed a couple of signs of recognition. “I look forward to renewing old acquaintances, and making new ones in the short time I’m here.”

That was not really true. My real hope was that my brief return to Myerton would be quiet and uneventful. I was only at Saint Clare’s because the Archbishop had ordered me there to fill in for Father Anthony. I had no more desire to stay than I had when I left everything behind ten years earlier.

I gave the final blessing, the final hymn started, and I proceeded down the aisle with the altar servers. I thanked everyone, then went outside.

The day was one of those sunny, clear days in mid-September which has the last taste of summer and the first taste of fall. It was warm, but with a cool breeze that made being outside in full mass garb tolerable.

I placed my hand against one of the six white marble columns that lined the portico. Saint Clare’s was an imposing structure, said to be one of the largest churches west of Baltimore. The white Ionic building was constructed in the 1850’s to replace the earlier brick parish that had burned. Funded by the small donations of Irish immigrants who made their way into the Allegheny Mountains to work on the railroad, as well as the larger ones of benefactors who employed them, the church had seen untold numbers of baptisms, as well as weddings and funerals.

Joan and I had stood under its soaring vaulted ceiling in front of friends and family as we exchanged our wedding vows. She wore white, looking impossibly beautiful that day, her veil covering her chestnut brown hair as it flowed gently over her lace-covered shoulders. Father Anthony, whose place I was taking, had officiated that day.

He also said her funeral mass, not five years later.

People began coming out. Children ran past, chased by frazzled moms hastily saying, “Thank you, Father,” as they hurried by. I shook hands, said, “Thank you very much” to people who said, “We’re glad you’re here” and “Good homily, Father.” No one I recognized at first. Then, a large man about my age stopped. With him were two twin teenage boys. Leaning on a cane, he extended a beefy hand. I laughed, grasped his hand, and gave him a hug.

“John Archman,” I said, “how are you?”

“Good to see you, Tom,” said the big bear of a man. “Or maybe I should say Father Tom?”

“Tom’s fine. I didn’t know you were still living in Myerton.”

John nodded. “Chloe wanted to raise the kids here, it’s near her parents. And I like it too.”

“So, what are you doing now?”

“Consulting,” Archman said. “The new Tech Center outside of town.”

“Bit far away from DC for consulting, isn’t it?”

“Internet, teleconferences, you’d be surprised how little face-to-face time is required in IT consulting.” John turned to his boys. “John, Mark, say hello to your godfather.” The twins said hello then asked their dad if they could hang out with their friends until time to leave.

“Don’t make me come look for you,” John said as they ran off. When he turned back to me, he grimaced.

“You okay?” I asked.

“Yea,” he replied. “My leg still gets to me sometimes. I’ll have to get back into physical therapy.”

Soon after 9/11, John had enlisted. He served two tours in Iraq. During the second tour, an IED exploded as his squad was on patrol. He was the only survivor, and was himself severely wounded. “So,” he said, looking me up and down. “You’re a priest now. I’ve gotta tell you, I didn’t see that one coming.”

“You’re not the first one to say that to me. Is it that remarkable?”

“No, not remarkable, it's just—I remember what you and Joan were like together. You were inseparable. I envied you two that. Chloe and I—I’ve never seen two people in love as much as you two were—I knew how devastated you were after her—” John paused. “Joan was special,” he whispered.

“Yes she was,” I said quietly.

“Then you left and didn’t tell anyone where you were going. No one heard from you for a while. Then when Anna told us—none of us could believe it. ” He paused. “So how did it happen?”

It was a question I heard frequently, especially when people learned how old I was when I was ordained. Granted, most priests didn’t enter their vocation when they were thirty-six. Even fewer received the vocation after they were married. But my situation was different. So, I kept getting the question, one I was getting kind of tired of being asked.

“It’s kind of a long story,” I replied. “I don’t want to get into it right now.”

He held up his hands “Okay, okay. No problem. But you said you weren’t in a parish before here? What have you been doing?”

“I’ve been the archivist for the Archdiocese since my ordination, so I’ve been at the main office for five years. I was in a parish briefly at the beginning, but it didn’t work out.” Another subject I didn’t want to get into.

“Well,” he said smiling. “It is good to see you. Chloe will be sorry she missed you. Home with a sick kid. Hey, we’ll have to have you over for dinner. Catch up.”

I hesitated. “Maybe when I get the time. But give Chloe my best.”

John’s smile faded. “Sure, sure Tom. When you get the time. I’ll tell Chloe you send your best.” I watched as John, leaning on his cane, went off to find his boys.

“So you’ve seen John,” Anna said, having come up behind me. I turned.

“He’s missed you,” she said. “You were his best friend.”

“And he was mine.”

“He could have used a friend like you over the last few years.”

I looked at her, puzzled. “He hasn’t had an easy time since you left,” she explained.

“He seems fine to me, except for the cane.”

“Looks are deceiving. He’s struggling. Chloe tells me these last few years have been hard.”

I remembered how John was after he came home. The physical wounds were slow to heal. The emotional wounds festered. Joan and I were as supportive as we could be, but after a while John just withdrew.

I looked at her. I didn’t know how to answer.

“Anyway,” she smiled. “Good job. Everyone seemed really pleased.”

“Except Glenda.”

“Oh,” she waved her hand, “don’t worry about Glenda. She’s had the run of this place for years. It's about time someone stood up to her.”

“I didn’t want to cause a scene.”

“You didn’t. You did what Father Anthony should have done a long time ago. But Father Anthony isn’t inclined to confrontation. And Glenda is—”

“Yes, she certainly is.” The day I arrived Glenda Whitehall made it very clear what she thought of me.

“I don’t know why the Archbishop sent you,” she had said. “Father Anthony’s coming back. He doesn’t need to be replaced.”

“I’m not replacing Father Anthony,” I had said. “I’m just here for four months while he....rests.”

“We can get along just fine having a priest show up for mass,” she went on like I hadn’t said anything. “When I spoke to the Archbishop—”

“You called the Archbishop?”

“—I told him we didn’t need a resident priest. I asked him just to send one around for mass on Saturday nights and Sundays. He gave me some hogwash about a parish needing to have a resident priest. I told him exactly what I thought.”

She went on like that, all the while showing me through the rectory, a two-story house sitting next door to the church. A covered walk from the front door led to what I assumed was the sacristy. Another path led to the sidewalk. The first floor had a reception area, office, a meeting room and a small chapel. Upstairs were three bedrooms—Father Anthony’s and two guest rooms, including the one where I would be staying—a small study, and a kitchen and eating area. The furnishings looked like rejects from Mike and Carol Brady’s home, frankly hideous shades of brown, yellow, and that tried and true staple of the 1970’s color scheme, avocado. There was a worn and threadbear quality to the whole place, much like Whitemill herself.

I realized I had not seen Glenda coming out of the church. Not knowing where she was made me nervous. I looked around in the crowd.

I finally spotted her. She was standing on the corner, speaking to a man about my age. He was about my height and wore a pullover hoodie and jeans that hung loosely about his frame, showing he was quite a bit skinnier than I was.

“Who is that?” I asked Anna.

She turned. “Who?”

“That guy over there talking to Glenda.” They were too far away to hear, but she was shaking her right finger in his face, and he was shaking his head emphatically.

“Hmm,” Anna said. “I’m not sure. I know Glenda has a nephew, and that could be him, but I can’t say for sure. Not sure I’ve ever seen him.”

The man stormed away from Glenda, who just stood looking after him.

“He’s not a member of the parish?”

“I don’t know—he could be, and just comes to the earlier service. Or only shows up at Christmas and Easter, I really can’t say. I don’t know everybody, Tom.”

Glenda turned. She looked upset. Looking around to make sure no one had observed the scene, she walked quickly down the sidewalk to the Rectory.

The crowd had thinned out so there were only a couple of small groups talking to each other, their children running up and down the steps. Some had started an impromptu game of tag on the grass between the church and the parking lot. In a couple of minutes I’d be able to go inside, take my vestments off, then spend the rest of the afternoon resting.

“Why don’t you come over for lunch,” Anna said. “ Nothing fancy, just sandwiches.”

I hesitated. “Anna, I’m kinda tired—”

“I’m going to see her this afternoon,” Anna went on. She paused to let that settle in.

“It’s been a long day,” I said. “I’m really drained. Maybe another day.”

She looked at me, not saying anything. I saw the accusatory look in her eyes and braced myself. Then she smiled.

“It’s okay, Tom,” she patted me on the arm. “Some other time.” She began to walk away, then turned and said, “I’m sure she likes them.”

“Likes what?”

“The carnations,” Anna said. I shook my head. “The peppermint carnations?”

Peppermint carnations. Joan’s favorite flower.

“What about peppermint carnations?” I said, thoroughly confused.

“You really don’t know what I’m talking about,” Anna said. “You haven’t been sending peppermint carnations to her gravesite once a month?”

“No, it isn’t me,” I said. “Sorry.”

Anna sighed. “Oh. I just assumed. Guess one of her friends.” She began to walk away.

“For how long?”

“It’s been a long time. Almost ten years,” she said over her shoulder. “I thought it was you. Guess I was wrong.”

I walked back into the church. In the sacristy, I took off my vestments and turned the lights off in the church. I looked around. The only light came through the stained glass windows and the candles. Incense still hung in the air; I could also smell the oil on my hands from anointing the Reynolds baby. The building was at peace.

I was not.

Two

Monday is a parish priest’s traditional day off. Since arriving at Saint Clare’s I had not had the time to learn about the parish or get my office organized. There were files on the desk, put there by Glenda I assumed, that I needed to go through. After my first cup of coffee and morning prayer, I sat down at the desk and began to familiarize myself with the parish. I knew I would have a couple of hours of silence because Glenda was out.

After thirty minutes, my eyes began to glaze over. I’ve never had much of a head for numbers, and trying to make sense of Saint Clare’s financial statements was taxing my limited powers to the utmost. I couldn’t tell if the parish was running a deficit, had a surplus, or was breaking even. From what I knew of other parishes around the country, the truth was probably somewhere in the middle.

I plowed ahead with another folder labeled baptisms and confirmations. While Saint Clare’s did not have a lot of money, it was rich with people. Since January, twenty babies had been baptized into the Church; also, four adults entered the Church the previous Easter and five more were preparing to join the next. The folder on religious education also showed good, healthy numbers. Whatever was going on in the parish, it was good.

The doorbell rang. I didn’t get up at first, because I thought Glenda would get it. By the third ring, more insistent this time, I remembered she was still out. I went to open the door.

On the front stoop was the man I saw Glenda talking with the previous day.

He seemed surprised to see me. “Good morning,” I said.

He didn’t speak at first. He looked like he was in a daze. I couldn’t tell if he was high or just confused.

I tried again. “Can I help you?”

“Huh?—Oh, yeah, sorry Father,” he finally said. “Is, ah, is—is Glenda here?”

“No, she’s out right now. She should be back soon, Would you like to come in?” I opened the door wider so he could come in.

“No, no, no, that’s—that’s okay, Father. I’ll, ah, I’ll just call her later—”

“—Is there something I can help you with?”

“You?” He seemed shocked by the question.

“It is kind of what I’m supposed to do, help people. Comes with the collar.” I smiled, hoping the joke would put him at ease.

It didn’t work. “No, no, I’ll just get Glenda later. Sorry to bother you.” He turned and walked off, looking back over his shoulder at me.

“What’s your name so I can tell her you stopped by?” I called after him. He didn’t answer me. I stood looking after him.

I went back to my desk and picked up where I left off. I had only been back at work for a half an hour or so when the doorbell rang again. I looked up from my papers to the general direction the sound was coming from.

“Some day off,” I said.

This time, it was a woman at the door, one I recognized.

“Hello, Chloe,” I smiled.

Chloe Archman smiled. It was the smile of a person who had the choice of either laughter or tears, and chose laughter only because it wasn’t socially awkward.

“Hi Tom—Father Tom,” she said.

“Tom’s fine, Chloe. Please, come in.” We hugged, and I showed her into the small sitting room opposite my office. She sat on the edge of the couch, hands folded in her lap. I sat opposite her in an ugly seventies-brown armchair. A spring poked me in the back.

“Sorry I missed you at Mass,” I said. “John told me one of the kids is sick. Are they better?”

“Oh, yes, she’s doing much better. A twenty-four hour thing. The kids are at home. We homeschool but someone comes in to watch them a couple of mornings a week. I teach one class per semester at the college.”

“So you’re back teaching. English lit, wasn’t it?”

“Yes.” She paused. “So, how have you been?”

“Fine, fine.”

“Good, good.”

There were a few moments of silence. We just looked at each other.

“Can I get you something to drink? Water, coffee?”

“No I’m fine.” She sighed. “Sorry, this is harder than I thought it would be.”

“What is?”

“Coming here. Seeing you—my best friend’s husband—for the first time in ten years. You know, I thought about what I’d say when I finally saw you—oh, I had some choice words in mind for you. Leaving without saying good-bye. Not coming back one day in ten years. Not a card, not an email, not so much as a text. The only thing we ever heard was from Anna—we couldn’t believe it when she told us—so at least we knew you weren’t dead. I was so, so angry, with so many things to say. But I can’t say any of it now because you—”she gestured with both arms “—are now a priest.”

I nodded.

“Worse, you’re my priest,” she continued. “So is it a grave sin to be angry at a priest?”

“No graver than being angry at anyone else.”

“Oh, okay, well—I’m angry at you, Tom. Really, really angry. You left Anna, you left John, you left me. You were the only connection I still had to my best friend. I was devastated when she was murdered. I was devastated when you left. But you know what, not nearly as devastated as John.”

“John?”

I could see tears beginning to form in her eyes.

“Oh, Tom!” She cried, and buried her face in her hands. I grabbed a nearby box of tissue and handed it to her. She took out a couple and wiped her eyes.

“Anna told me he’s had some problems.”

“Not just some problems, Tom. Oh, you don’t know, but then how could you—you weren’t here.”

“Well I’m here now. Tell me what’s going on.”

She exhaled. “After he came home from the hospital, he seemed to be doing well—I guess as well as could be expected. He was still in pain, but the physical therapy was helping and he was working hard at it. He got stronger, he was seeing a therapist to help him process what happened, he was becoming the John I knew. Well, you remember how he was.”

“I remember. After a while, he seemed like the old John.”

“He was doing so well,” Chloe said. “Then, he began to change. He became withdrawn, spending more and more time by himself. He didn’t want to see anyone or do anything. He spent all his free time either locked in his office or taking long walks by himself.” She paused and wiped her eyes as the tears began to return. Then she looked at me, rage returning to her voice.

“And, by the way, you and Joan were not much help. It seemed like everytime we wanted to do something, Joan was too busy with her new business.”

I lowered my head, knowing that what she said was true. Joan was so busy back then, trying to get her design business off the ground. But I also remembered a few times when I tried to get John out for a boys night, only to have him turn me down. I was hurt at the time, but now I realized I should have dug deeper, reached out to him more when he needed me.

I was wrestling with these thoughts while Chloe continued, now in the voice of spent, rather than active, rage. “Not long before you left, his leg began bothering him—he reinjured it somehow, he thinks when he tripped on the back stairs while taking the trash out.”

“That’s why he uses the cane,” I said.

Chloe nodded. “But before that,” she went on, “his mood changed. His depression got worse and he began having nightmares. He started drinking. When he reinjured his leg, he couldn’t get around without the cane. He’s been in pain ever since. He won’t do physical therapy anymore—says it's voodoo, doesn’t work, I don’t know when he decided that—just takes pain killers and drinks.” A tear snaked its way down her cheek. “But I can handle the physical pain. That doesn’t worry me as much as the other.”

“What other?”

“The moods. The depression,” she said. “He’ll be happy one minute, then screaming with rage the next.”

That didn’t sound like the John I knew. “Has he ever hurt you or the kids?”

“Oh no, no, he’s never laid a hand on us. He has the presence of mind to go scream in the garage when he’s really angry. I think he knows I’d leave if he ever did anything like that.”

“He needs to get help, Chloe,” I said. “Before he hurts someone.”

“I’m more concerned about him hurting himself. When he’s really down, he begins to talk about how he’s responsible. That it’s his fault people died. He says he’s a coward, how he should have done something to help instead of hiding, about how he betrayed them, about how the wrong people always die.”

“But that makes no sense,” I said. “He received a commendation. There’s no way any of that in Iraq was his fault.”

“I know. But he’s been carrying a big load of guilt for a long time.”

Guilt. That was something I knew about.

“Is he seeing anyone?”

“No, not anymore,” she said. “He did for a while, see both a therapist and a psychiatrist, right after he came home. It was helping.” She shrugged. “Then he stopped.”

“Why’d he do that?”

“Well, he told me he didn’t need to go anymore, but I don’t know the real reason.” She sat back and sighed. “I’m about at the end of my rope. I was wondering if maybe you could talk to him?

“I’ll try,” I said. “But I don’t know what I can do.”

“You were—are—his friend. He used to listen to you. I’ve run out of ideas. Besides, you’re a priest.”

“That doesn’t give me a magic skill. He’ll have to want to talk to me. He’ll have to want help. Do you think he does?”

She thought for a moment. “I don’t know. I really don’t know.”

I sighed. “Okay, Chloe. I’ll try talking to him. In the meantime, I’ll keep you and your family in my prayers.”

She smiled, a real smile this time. “Thank you, Tom. Thank you so much.”

After she left, I had settled back into my study with another folder, this time on the Knights of Columbus, when I heard the front door open. What sounded like two people came in.

“There’s no reason to bother the Father about this,” Glenda said.

“I just want to ask him if he would mind if we had one this year,” a young woman replied.

“Father Anthony has said no each year for the past five years,” Glenda continued. “It would be just too disruptive.”

“Well Father Anthony’s not here, and it will not be disruptive. We’re just talking about a small, simple production—”

“You will not talk to Father about this because—”

By this time I was standing in the doorway. The young blond woman with Glenda was one I recognized from the 10:30 a.m. service sitting with her husband and four blond children.

“Glenda,” I interrupted. They looked at me.

“Oh, Father,” Glenda said. “I was just telling Miriam that—”

“Thank you, Glenda, but why don’t you let Miriam talk. Miriam, you had something you wanted to ask me?”

“Well—yes, yes Father Tom,” Miriam said. “I wanted to ask—well, some of the other moms in the parish thought—you see, Christmas is in a few months—

“Yes, that seems to happen every year,” I said. Smiling, I added “What would you like?”

Miriam inhaled, then slowly exhaled. “We were wondering if you would approve us getting some of the children to do a nativity pageant.”

“You mean the children playing the various parts, Mary, Joseph, shepherds, kings. A few toddlers dressed as sheep.”

Glenda interjected. “I told her it would be impossible, Father.”

“Really, and why is that, Glenda?”

She seemed stunned that I would question her statement. “Well, well—it just would be. The Advent and Christmas season is just so busy, and the children would disrupt everything.”

“Now Glenda, if Saint Clare’s could survive being used as a hospital during the Civil War, I think it can survive a small nativity play.” I turned to Miriam. “Sounds like a fine idea, Miriam—what is your last name?”

“Conway. Miriam Conway. Thank you Father, thank you so much. Now we thought maybe Saturday, a week before Christmas.”

“Actually I have an idea. Isn’t there a Christmas Eve vigil mass, Glenda?”

“Yesss, at 5:00.”

“Good. Why don’t you do it at the Vigil Mass?”

Miriam smiled, “Really?”

“At the Vigil Mass?” Glenda was not smiling.

“Yes. I would think that mass would have a lot of children attending, parents wanting them to get to bed early. It would be fun for them. We’d do it instead of the homily. What do you think, Miriam, do you think everyone would go for that?”

“Absolutely! Thank you, thank you Father. This means a whole lot to us—more than you can know.”

Miriam shook my hand, made a face at Glenda, and left. After she was gone, Glenda turned to me.

“Father Anthony—”

“Is not here, Glenda. Let me ask you, just between you and me, did he ever actually tell the ladies he didn’t want a nativity play?”

Glenda hesitated. “Well, well, not exactly—”

“I thought so.” I paused. “Glenda, I understand that you spent a lot of time acting as Father Anthony’s gatekeeper. I’m sure he appreciated it. But you don’t need to do that with me.”

“You cannot spend your time talking to every parishioner who wants your attention.”

“I know, but I can speak to most of them,” I said. “From now on, I’m available for anyone who wants to talk to me during office hours.”

“Father Anthony didn’t keep office hours. People had to make an appointment.”

“Well they can make an appointment, but if they stop by and I’m here and I’m not in the middle of something critical, I’ll be available to them. Okay?”

Glenda stiffened. “Yes, Father. If you’ll excuse me, I have to put the groceries away and start dinner. You’re having chicken tonight.” She grabbed her bags and stormed out.

“Oh Glenda,” I called. She stopped in the doorway and turned slightly. “Someone stopped by to see you.”

“Who?”

“I don’t know his name. I saw you talking to him yesterday after church. Anna thought it was your nephew.”

The blood rushed from her face. “He, my, he stopped by the rectory while you were here?”

I furrowed my brow. “Yes, it was while you were out. Is everything okay Glenda?”

“What—yes,” she said, squaring her shoulders, “Oh yes, Father, everything is fine. I’ll call him after I finish lunch. I’m sorry he bothered you.”

“It was no bother, Glenda. I didn’t know you have a nephew. Does he live with you?”

“Yes, yes, Roger, he’s my sister’s son,” she said quickly. “He’s staying with me while he works a construction job at the College. I’ll call him in a bit.”

She had just cleared the doorway when the phone rang. I looked at the clock. It was just eleven. I had to be in the church by 11:30 to get ready for the Noon Mass.

“Lot more lively place than I thought it would be,” I mumbled to myself. I picked up the phone.

“Hello, Saint Clare’s rectory.”

“May I speak to Father Tom Greer, please?”

“Speaking.”

“Oh, Father Greer, good. My name is Nate Rodriguez. I’m a freelance documentary filmmaker.”

“What can I do for you?”

“I was wondering if I could interview you for my next film project.”

“Me? Why would you want to interview me?”

“Well, you see, my project concerns an unsolved murder.”

I froze. “An unsolved murder?” I said slowly.

“Yes. The unsolved murder of Joan Greer.”

Three

“I know this was short notice, but I really appreciate you agreeing to talk to me,” Nate Rodriguez said, adjusting his glasses.

“Let me be clear, Mr. Rodriguez—”

“Nate, please call me Nate.”

“Okay, let me be clear, Nate,” I said. “I have not agreed to anything. I only said I would meet with you.”

It was two hours after he called the rectory that I found myself sitting across from this very earnest young man with a hipster beard and glasses, wearing a red plaid shirt at a coffee shop, the Perfect Cup, across Main Street from Myer College. The stone archway people considered the main entrance to the campus was just opposite where I sat.

Dominating the scene was the statute of Winthrop Myer, founder to Myerton and the College. Myer had arrived in the Western Maryland mountains having gained and lost one fortune in Baltimore. On the frontier, he built another on lumber and the railroad. He had dreamed of the mountain town rivaling Baltimore or Pittsburgh in size and wealth, with Myer College becoming the Johns Hopkins of the Alleghenies.

I looked at the young boys and girls, books in hand, backpacks on their backs, walking to class or back to their apartments. It was not far from that spot that I had met Joan.

I had just started working at the college’s archives, my first job after getting my Master of Library Science degree. One day in early March I was walking along, not paying attention to where I was going—I was reading something, don’t remember what—when I walked into a young woman, knocking her down and sending a large drawing portfolio flying out of her hands. The portfolio had a broken zipper, and it was a windy day, so in the next moment drawings and watercolors began flying all over the place.

“Hey, clumsy oaf,” she yelled, “why don’t you watch where you’re going? Look what you’ve done!”

“I’m sorry,” I said, still trying to process who would use the phrase “clumsy oaf” in a small mountain town in the twenty-first century. “I’ll help you get them back.”

“Yes, you will,” she replied as she began chasing after her drawings. I followed after her, grabbing sketches and watercolors cartwheeling across the lawn, all the while keeping my eye on this woman. Unlike most of the female students and faculty on campus, she didn’t wear jeans; instead she wore a long denim skirt that flowed after her as she ran and was blown by the wind. That day she had paired it with a red turtleneck. Covering her long chestnut-brown hair was a wide-brimmed black cloth hat that managed to stay on, I later found out, through the use of a long and formidable looking hat pin.

We managed to get the drawings gathered up, and we sat on a nearby bench. I handed her my stack. “I hope they’re okay,” I said.

She looked at each one as she placed them back in the portfolio. “They look no worse for wear, no thanks to you.”

“I did say I was sorry,” I replied. She looked at me, her blue eyes still flashing irritation. I smiled, trying to disarm her. It worked, because her frown turned into a smile and her eyes softened.

“Well, thank you for helping me get them back,” she said. “I don’t have time to redo this project.” She stood up to go. “I’m Joan Luckgold , by the way.”

“Tom Greer,” I replied as I stood. We stood there on the sidewalk, students passing us on their way to or from classes, looking at each other.

“Okay,” Joan said, “I guess I’ll see you around campus.” She turned and took two steps away from me.

“Are you hungry?” I called out. She turned. “I mean, I haven’t had lunch yet, and I thought—-”

“Come on,” she said, sweeping past me. Over her shoulder she said, “You’re buying.”

We wound up at Marlowe’s, a restaurant in a small Victorian house not far from campus. She had the Cobb salad, I had the tomato bisque and four-cheese grilled cheese. I didn’t know why I had asked her to lunch. I had been in a long-term relationship that had ended less than ideally, and I wasn’t looking for another one. But I had knocked her down, and I was responsible for her almost losing her artwork. Lunch seemed an appropriate apology. That’s all it was.

We were married a year later.

“I’ll be glad for any help you can give,” Rodriguez said, bringing me back to the present.

“Let’s just slow down a bit,” I replied.

“Sure, sure, okay.”

I stirred my coffee. “So, you make documentaries?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“Anything I might have heard of?”

He shook his head. “No, no, nothing—well, actually, I’ve only done a few small projects for my classes at Myer, so this is the first big project I’ve worked on.”

“I see,” I replied. “You went to Myer?”

“Uh-huh, graduated two, three years ago. Got my degree in journalism.”

“Are you working for the Myerton Gazette?”

“Ah, well, not exactly.” He took a drink of coffee. “I actually work here.”

“Here,” I repeated. “At The Perfect Cup. As a—?”

He shrugged. “Whatever my uncle tells me to do—wait tables, bus tables, barista. Listen, Father, can we get on with it? I only get thirty minutes for lunch.”

I wondered even more what I was doing there. “Let me see if I understand correctly,” I said. “Your project is to investigate—-”

“Okay, well, investigate is probably too strong a word. I’m not really investigating your wife’s murder—can I call her your wife, I mean, with you being a priest?”

I sighed. “Obviously I was not a priest when I was married to Joan. You can call her my wife.”

“Okay, okay, well, your wife. So the project isn’t to try and find who killed her—though I gotta tell you Father, that would just be so cool.” He stopped himself when he saw the expression on my face. “I’m sorry, I don’t mean cool cool, just, you know, finding justice after all this time—”

I held up my hand. “So what exactly is your project?”

He took a deep breath. “I was looking for a project for my next film, so I was doing research in the files of the Myerton Gazette and came across stories about the murder. You know, Myerton is a relatively small town. Murders don’t happen every day. The way it happened, no one was caught—it got a lot of attention.”

I nodded. He was right. At the time, Joan had been the first person murdered in Myerton in a couple of years. The paper covered it extensively. Reporters from as far away as Baltimore came and did stories for a few days afterwards.

“So it got me thinking,” Nate continued, “about what happens after the news cameras leave and the paper stops writing articles. What about the people left behind? How do they cope? How did it change them? I mean, in your case—”

“Yes, yes, I see what you’re getting at.”

“So I’ve already done several interviews, researched the case, looked at the police file—”

“You got a copy of the police file?”

“Oh yes, you can get almost anything through a Freedom of Information request. There’s some portions blacked out, but it's been helpful. So I have that.”

“Who have you interviewed?”

He pulled out a notebook. “Let’s see, some people who knew her from college, her mother—”

“You interviewed Anna?” I wondered why she hadn’t given me a heads up about this guy.

“Yea, Mrs. Luckgold was great—very helpful. Gave me some great pictures and video to use.” He looked through his notes. “The owner of the gallery up the street, the Painted Lotus, she did an interview.”

“Bethany Grabble’s still in town?” She was a friend and colleague of Joan’s from Myer’s Fine Arts Department.

“Yea, she gave me all sorts of insights about who she was.”

One name was conspicuously absent. “Did you interview Chloe Archman?”

Rodriguez sighed. “No. She refused to talk to me.”

“Really? Did she say why?”

“No,” he shook his head. “She just said she didn’t want to talk to anyone about Joan Greer.”

I found that very odd. They were best friends, after all. Practically inseparable. Chloe had been Joan’s Matron of Honor at our wedding, like John had been my best man. If Anna would agree to participate, why wouldn’t Chloe?

And if Chloe didn’t, why should I?

I took a sip of my coffee. I’d let it get cold.

Putting my mug down, I said. “Nate, I wish I could help you, but—”

“Oh please,” he said, looking at me anxiously. “Don’t say but. Look, I’ve done a lot of work. It’s good, I mean I think it’s good, but there’s a big hole in it. That’s why I was so glad that Mrs. Luckgold called and told me you were back in town.”

“Anna told you I was back in town?”

“Yes, and I was so glad. I had tried to track you down, but after you left Myerton you kind of disappeared for a while.”

“Yes, I wanted it that way.”

“So then you came back here, and I thought, wow, just in time, he’s exactly what I need to really finish this. The victim’s husband. The man whose arms she died in.”

The night was a blur. Joan laying in my arms, gasping, the blood. Cold steel against my forehead. A painful throbbing in my temples. And the sound.

Click. Click. Click.

“I really, really need you for this, Father Tom,” Nate concluded.

I shook my head. “No. That night is not something I want to talk about. If you have the police report, you have my statement. I can’t help you.” I got up to leave.

Nate stood. “Father, please, just think about it. You know, one thing I keep coming back to in this, everyone I’ve talked to says how much they needed closure, how her murder not being solved never gave them closure. How it was just so senseless, the attempted rape, there not being another case like it. What if this film, well, maybe jogs someone’s memory? Maybe it could give the cops a lead. Who knows, maybe this film could help finally solve your wife’s murder?”