Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: David McCloskey spy thriller

- Sprache: Englisch

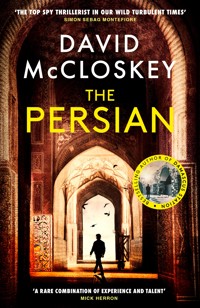

'A superb and compelling espionage drama inside the Iran Israel shadow war by the top spy thrillerist of these wild turbulent times' Simon Sebag Montefiore 'A great spy writer' Tim Shipman What happens when a spy is forced to reckon with the consequences of his deception? Kamran Esfahani, a Persian Jewish dentist from Stockholm, dreams of starting afresh in California. To finance his new life, he agrees to spy for Mossad in Iran, working with a clandestine unit tasked with sowing chaos and sabotage inside the country. When he's captured by Iranian security forces, Kamran is compelled to confess his experiences as a spy, in a testimonial dealing not only with the security of nations, but also with revenge, deceit, and the power of love and forgiveness in a world of lies. Mixing suspense with strikingly cinematic action, David McCloskey takes readers deep into the shadow war between Iran and Israel, delivering propulsive storytelling and riveting tradecraft. THE FOURTH NOVEL FROM FORMER CIA OFFICER, THE REST IS CLASSIFIED PODCAST CO-HOST AND THE BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF ***THE TIMES THRILLER OF THE YEAR***DAMASCUS STATION ('One of the best spy thrillers in years' THE TIMES) AND ***SUNDAY TIMES BOOK OF THE YEAR*** MOSCOW X READER REVIEWS 'A brilliant gripping read. This is one of his best books' 'An excellent read from the pen of one who has been there and done it all, especially in light of current events in the Middle East.' 'This is the best book I have read in years. A superb spy novel.' 'Couldn't put it down, this is an amazing book...This is a must read from a great writer!'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 563

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE

PERSIAN

ALSO BY DAVID Mc CLOSKEY

The Seventh FloorMoscow XDamascus Station

As always for Abby, my loveAnd for the people of Israel and Iran, for hope, and a new way

Love comes with a knife.

— R Ū M Ī

PROLOGUE

Tehran, IranFour years ago

IT DID NOT ESCAPE the Israeli watching through the hijacked phone camera that this very scene had unrolled that morning at his own breakfast table in Tel Aviv. His daughter was about the same age—even the nail polish had been pink.

—

ROYA SHABANI BLEW ACROSS her daughter’s freshly painted fingernails. Alya, ever a mimic, took a deep breath and huffed as hard as she could across the bright pink polish.

“Who’s coming to my party?” Alya asked, watching her mother screw the cap onto the polish.

“Everyone you wanted. The list we made, sweetie.”

She began to stand, but Alya held her wrist tight. “How many?”

“Six,” Roya said.

“Will there be cake?”

“You and I made the cake,” Roya said. “We are bringing that.”

“Can I bring my lamby?”

“Of course,” Roya said. “Your lamb can come.”

Roya stood and glanced at the clock. “Why don’t we draw while we wait for Papa to finish working? Go get your paper and crayons.” As Alya hustled off, Roya strode over to Abbas’s office and raised her fist to knock on the door before she thought better of it. They were going to be late, even if traffic was light, which in central Tehran it never was. But why bother Abbas, and add his agitation to the mix? So she turned around, and headed for the bathroom to check the rings of kohl around her eyes and reapply the bright red lipstick that Abbas had once complimented.

Back in the living room, Alya slid her mother a few crayons and a sheet of paper, and Roya aimlessly began drawing. Something had been wrong for a few months now—late nights in the office, overnights, last-minute travel, always to places he would not name, and always with Colonel Ghorbani, his uncle. When he was home, he was joyless and distracted. At dinner he would stare off into the distance, as he’d done in the thick of his dissertation, which meant he was trying to work out a problem. Then, it had been amusing, endearing. Now it was worrisome. Abbas was not the cheating type, but Roya could not help but wonder if he was having an affair, or had taken a temporary wife.

Halfway through Roya’s second distracted attempt at drawing a fountain, with Alya’s ire rising that Maman could not do it right, the door to the office swung open and Abbas walked out while sliding on his jacket and trying his best to smile.

Alya darted to him, hands outstretched, and said, “Papa! See my nails?”

“Absolutely beautiful,” he said, making a show of admiring them while gathering her into his arms. “Are you ten today?”

“I’m five, Papa!” He kissed her head. Roya heard his phone buzz, and when he set Alya down he was back on it. An hour earlier, while getting ready, Roya had entertained a brief fantasy that the night would offer some connection with Abbas, a chance to talk at dinner, to admire their daughter, and, if lovemaking wasn’t in the cards, at least to go to bed at the same time. But she could see his mind was elsewhere, and that made hers itch for cigarettes, which Abbas hated. He wasn’t a prayer-and-fasting type—though both Shabanis occasionally had to put on a show for his job. No, his objection was rather the smell, which he said made him queasy. Though maybe after dinner, and once Alya was asleep, he would return to the office? She hated that, which was where the cigarettes came in . . .

—

TRAFFIC WAS A GRIND as they inched northbound from Yusef Abad up to the restaurant off Jordan Avenue; not a drive any Tehrani wanted to make in rush hour, but this was where the Shabanis went to celebrate birthdays. Not the sort of ritual a newly minted five-year-old girl was likely to let you break. Alya was singing to the stuffed lamb in the backseat, occasionally interjecting, “Ugggh, why so slow, Papa?”

“Traffic, love,” Roya said. “Papa is going as fast as he can.” As they were passing a sycamore-lined median, Alya began singing again. This time it wasn’t nonsense, it was a nursery rhyme, the one about the little chicken and the pool, a bathtime favorite. For a moment, with all of them together in the car, the singing made Roya feel warm and cozy. Tonight they might actually have fun.

Abbas’s phone began to light up and buzz with incoming messages.

“I’m picking up the shoes tomorrow,” Roya said, while Abbas typed out a message on his phone.

No response, except a few angry honks from the car behind them.

“Abbas?”

“Oh, what?” Face still fastened to the phone.

“I said I’m picking up your shoes tomorrow. The ones I had made for your birthday.”

“That’s great. That’s great.”

No sooner had he put his phone down than it would blink and buzz again. The traffic, the toddler singsong—which was growing quite loud—the honks . . . Roya rifled through her purse and tossed it back at her feet in a huff. A mistake, she thought, not to bring the cigarettes.

“Does your uncle know it’s her birthday?”

“What? I don’t know.”

The traffic was loosening; the car in front puttered ahead. Roya looked at Abbas, who was looking at his phone.

“Abbas, go.”

“Oh.” The phone clattered into the cupholder, Abbas jerked the car forward. They drove in silence for a few moments. Alya had stopped singing. All Roya could hear was the beep and buzz of his phone.

“Colonel Ghorbani,” Roya said, emphasizing his uncle’s rank, which Abbas hated, “told me at your birthday dinner that you might be his nephew, but you’re like a son to him. So how does he not know it’s her birthday?”

“I told you, Roya, I don’t know what he knows.”

“Maybe you could tell him, then? When the car stops again and you pick up the phone? So we can enjoy dinner.”

“Only some of it is my uncle,” Abbas said. He looked down at his phone and then seemed to catch Roya glaring at him. He drifted his eyes back to the road, chastened.

There had been plenty of times in the past month when Roya had wanted to take her husband by the shoulders and shout: You’re a scientist! You’re supposed to be sitting alone in a lab! She regretted his decision to reject the postdoc opportunity in Paris in favor of Colonel Jaffar Ghorbani and whatever his group was doing. “I design materials that radars can’t see,” Abbas had said once. That was all she knew. That was all she was going to get.

When they exited the highway they made a right and then, after a few blocks, turned down a road that would send them right back the way they’d come, but this time on the same side of the street as the restaurant. Roya looked out the window at a van up on the curb. One front tire was missing and it was up on a jack. Abandoned. Another Tehrani driver throwing in the towel.

“Auntie will be there?” Alya said.

“Yes, sweetheart, she’s already there. Auntie’s waiting for us.”

“I can have cake now?” Roya turned and saw Alya eyeing the cake, sitting beside her in the backseat.

“Not now, sweetheart,” Roya said. “We’re almost there.”

Abbas slowed the car for a speed bump, the restaurant just ahead. Alya began singing again. “Lili lili hozak . . .”

Roya spotted a little market she knew carried packs of cigarettes smuggled in from Dubai. Maybe she could send her sister, Afsaneh, to snag one for her, assuming Roya couldn’t slip away while pretending to use the bathroom.

Her thoughts were interrupted by a loud crack as the windshield spiderwebbed, and Roya thought someone had thrown a stone into the glass. Abbas let out a strange yelp. The car had been rolling so slowly that it bounced to a stop against the speed bump. There were pieces of glass on her lap. Air was rushing in.

“Abbas!” she screamed.

“I can’t see,” he yelled, “I can’t see.” Abbas yanked off his seat belt and smacked wildly at the door handle. Then Roya saw it, a shard of glass protruding from his eye, glimmering under the streetlights. Blood was trickling down his face.

“Abbas!”

When he got the door open Abbas fell out into the street. Alya was screaming in terror. Roya was, too, but their screams were drowned out by the roar of more gunfire. Abbas was flailing and jerking around, and then she saw a ruddy brown spray jet loose from his body, she didn’t know what it was, but the shooting stopped and the car was momentarily quiet except for Alya’s screaming. “Abbas!” she yelled, but he didn’t move, didn’t speak, and then she’d opened her own door and was crawling, reaching up to grasp around for the handle of the back door. The gun thundered again, a short burst, and then stopped. Roya was splayed across the cake, wrenching Alya free from her car seat, pulling her out. “Abbas!” she called. “Abbas!” The only response was another round of gunfire.

Papa, Papa, Papa, the girl was screaming. Roya was turning and twisting, trying to figure which way to run—she didn’t know where the shooter was—when her eyes fell on a blue Zamyad pickup. She felt the explosion in her teeth, in her bones. She was staring at its white-orange center, and it felt like the light was searing her eyes. A hulk of metal lifted from the bed of the truck, shooting skyward like the takeoff of a rocket.

With Alya slung over her shoulder, Roya turned and ran.

—

IN AN UNMARKED limestone building outside Tel Aviv, the Israeli squeezed the shoulder of a woman sitting at a computer terminal, and said she’d done well. A small group was clustered in the operations room, and no one was talking. The only noise had been the sound of gunfire in Tehran, nearly two thousand kilometers away. The woman lifted her hand from the joystick that was tethered, by satellite uplink, to a Belgian-made FN MAG machine gun. The kill order had been clear, as they always were: No collateral damage. And that included the young scientist’s family.

The Israeli watched the survivors run. In the grainy feed he made out a stuffed pink lamb flopping against the new widow’s back, clutched tight in the little girl’s pink-painted grip.

The Interrogation RoomLocation: Present day

“WHERE AMI, General?”

Kamran Esfahani loads his questions with a tone of slavish deference because, though the man resembles a kindly Persian grandfather, he is, in the main, a psychopath.

The General is looking hard at Kam. He plucks a sugar cube from the bowl on the table, tucks it between his teeth, and sips his tea. Kam typically would not ask such questions, but, during the three years spent in his care, hustled constantly between makeshift prisons, he has never once sat across from the General, clothed properly, with a steaming cup of tea at his fingertips, a spoon on the table, and a window at his back.

Something flashes through the General’s eyes and it tells Kam that he will deeply regret asking the question again. It has been over a year since the General last beat him or strung him up in what his captors call the Chicken Kebab, but the memories are fresh each morning. Kam can still see the glint of the pipe brought down on his leg, can still remember how the pain bent time into an arc that stretched into eternity, and how that glimpse into the void filled him with a despair so powerful that it surely has no name, at least not in Persian, Swedish, or English, the three languages he speaks. And he’s got more than the memories, of course. He’s got blurry vision in his left eye and a permanent hitch in his stride.

What is the spoon doing here? A spoon!

Two thousand seven hundred and twenty-one consecutive meals have been served, without utensils, on rubber discs, so Kam can’t help but blink suspiciously at the spoon. A mirage? An eyeball scooper? A test? Perhaps the General plans to skin the fingers that pick it up? The General calms his fears with a nod, a genuine one, which Kam knows looks quite different from the version he uses for trickery, for lulling him into thinking there will be no physical harm. Kam puts a lump of sugar into his tea and slowly picks up the spoon. He stirs, savoring the cold metal on his fingertips. He sets it down on the table and waits, listening to the soft metallic wobble as the bowl of the spoon comes to rest.

“You will write it down again,” the General says. He is rubbing the gray bristle on his neck, and Kam follows his eye contact as it settles on the portraits of the two Ayatollahs looking down from the wall above. When Kam was a child the sight of the Ayatollahs frightened him—it still does. He looks away.

How many times has he written it all down? Dozens, certainly. A hundred is probably closer. As if reading Kam’s thoughts, the General lowers his eyes from Khomeini and says, “One more time.”

Only once more? Are they finally going to kill him?

“May I use notes from my past testimonies?” Kam asks.

The General clicks his tongue. Translation: Hell, no.

“General,” Kam says, with a slight bow of his head, “I have already confessed to my crimes. I’ve hidden nothing.”

“Those,” the General says, wagging his finger, “are not the same thing.” And he gives a great laugh. Kam does not feel the cup slip from his fingers. He only feels the warm tea seeping into his pants and for a moment believes he’s wet himself. Kam has never heard the General laugh. He had assumed the man lacked even the lunatic’s sense of humor. Together they watch more tea run off the side of the table. Kam knows better than to stand without permission, so he just looks at the mess, and the General looks at him, more from curiosity than anger. The General could motion to the camera for a rag, but he does not. Nor does he motion for a new cup.

He instead pops a sugar cube in his mouth and chews on it as if it were a cracker. The General is the only person Kam has ever seen do this. A few times he has seen the man eat entire bowls of sugar cubes and once Kam even dared to suggest, from his long experience as a dentist, that the General give it up. But, for a man who asks so many questions, the General is also a terrible listener. He eats one more, licks a few grains from the corner of his mouth, and says, “You have confessed, yes. And what a list, eh? Sowing corruption on earth. Serving as a witting agent for the Zionist Entity. Breaking-and-entering. Robbery. Impersonating an official of the Islamic Republic. Wire fraud. Assault. Accomplice to murder. Fornication.” He begins to chew on another sugar cube and stares down Kam with the look of a man who despises fornicators because he desperately wants to be one. “You will write it again. And you will leave nothing out. It will be comprehensive, and final.”

Final? Kam considers another question. The General’s silent gaze screams: Do not.

“You will be clear on the chronology,” the General says. “You will be more careful than last time.” Kam knows that one of the surest roads to punishment is to throw fog around what happened when. The man is a real stickler for dates.

Kam nods, and makes it a nice, meek one.

Then the General motions to the camera hung in the corner.

It has been at least a year since the General’s last request for testimony; since then, Kam has worked diligently to forget the more painful parts, the ones that lock him in the past, in fantasies of endings he will never write.

Colonel Salar Askari, one of the General’s underlings, enters the room. He wears a patch over his left eye. Bizarrely it very nearly matches the color of his own skin, but that is only one of the reasons Kam does not like to look at him, and it’s not even close to the top. Around Askari floats the smell of rosewater and a predilection for forms of violence that in most places would be seen as sadism but here are treated more like paintings, with great potential for innovation and beauty. The muscles in Kam’s arms and legs and back clench tight, but then he sees that Askari’s hands are mercifully free of pipe, razors, cords, mystery creams, knives, leashes, terrariums, belts, vials, bags, rodent traps, sandpaper, or—the darkest possibility—lugging a bucket of water.

Unless it is contained in a small rubber cup, Kam no longer likes water. There’s been unpleasantness with water. In here, certainly, thanks to Askari’s buckets, big enough to submerge your head but not so big that there’s room to move it around. But more than anything, water reminds Kam of how he got here. And most days he’d take the General’s pipe over thoughts about that.

Instead of a bucket, Askari is carrying a thick stack of A4 paper and a shoebox filled with crayons, all the same shade of dark blue. Crayons are used for the writing drills because it is tricky to kill yourself with one. Kam suspects it is not impossible, though, and in his first grim months he nearly summoned the courage to give it a try. He might attempt it now, but for the knowledge that however they choose to kill him, it will be swifter, gentler, and far more certain than jamming a sharpened blue crayon into his eye socket, face-planting into the table, and plunging it into his brain. Also, now he’s got the spoon.

To his relief, the General dismisses Askari. Then he says, “Remember: this is your masterpiece, your magnum opus, your Nobel Prize winner.”

The General has variously accused Kam of representing the intelligence services of Israel, America, Britain, and Sweden. Kam finds the Nobel mention, with its nod to Sweden, land of his childhood, a good sign. The General tends to be less violent when he pretends to be interrogating a Swede. Kam’s optimism soars when he remembers that the Nobel cannot be awarded posthumously, and then, not for the first time, he realizes he’s overthinking it. That happens a lot in here. He’s got way too much time.

The General stands and claims one more cube. Kam hears the crunching of teeth on sugar and then the click of the door and the man is gone. Kam sorts through the box for a good crayon. Three years of writing, and he’s got standards. It’s the one spot in his life where he’s got some control, so he’s developed strong opinions on the proper tools for a confession. The crayon must be long enough. No nubs! When your big toenail is the crayon sharpener you don’t want to look at the nubs any longer, much less be forced to write with one. So it cannot be dull from the start. But it also cannot be so sharp as to risk a premature fracture. After Kam finds the one, he slides a piece of paper off the stack.

The first drafts, right after his capture three years ago, were utter shit, like all first drafts. To call them stories would be like calling the raw ingredients spread across your counter a meal. No, they were just a bunch of facts. Information wrung from his tortured lips and committed to bloodstained sheets of A4. But he knows he’s being too hard on himself. As a dentist, his writing had been limited to office memorandums and patient notes. As a spy, his cables adopted similarly clinical tones.

Just the facts, Glitzman, his handler, the man who’d recruited him to work for Mossad, liked to say. Leave the story to someone else.

Mossad had preferred he write in English, not Swedish. The General, of course, demands that he write in Persian. And it is in Persian that Kam has found his voice.

In those early months the torture and the writing were coiled together. When Kam was tortured, or deprived of sleep, or put into small boxes, he fantasized about writing, and when he was writing, he fantasized about torture. That hothouse produced the story. Or, more accurately, the stories. Kam has written his confession so many times that he’s developed a few different styles.

His first attempt at offering more than just the facts was a piece of faux-literary garbage that dragged on for about two crayons before an editorial session in the Chicken Kebab set him straight. Sometimes you get to finish the stories, and other times they finish you.

There is a spy version, of course. He hadn’t read much spy fiction before becoming a spy, but he’d binged crime thrillers and figured the guts of the two genres were probably not so different. The General was very determined to get the spy story out of him straightaway—that is why the literary attempt drew such fury. The spy stuff is what the General wants most of all, and Kam’s polished it to pure gold over who knows how many drafts.

There is also a love story, though lots of it is made up. That one can easily devolve into supermarket erotica, with multiple romances strewn across scenes as toe-curlingly salacious as they are pure joy to write. Though the General demands the spy story above all, Kam believes part of the reason he is still alive is that the General enjoys these spicier offerings.

As time went on, Kam grew foolhardy, and one week got a good many crayons into a Scandi crime version. Though the political and social commentary was appropriately sharp, and the crime at its center was darkly warped, the General did not appreciate that Kam had written in the first person from the General’s perspective as the investigator. A visit from Askari dashed all hopes of completing the draft.

The storytelling, though, was not the only blade to sharpen, so to speak. Kam’s fingers would shake constantly, rendering the handwriting illegible, he often bled on the papers, and would forget the basics—no page numbers, for instance. That incensed the General, who said it was a great disappointment to his readers. Kam was soon flogged to new levels of professionalism and clarity in his writing.

Now the cell becomes Kam’s scriptorium. In his dragging, tedious Persian script, he writes the Quranic inscription, “IN THE NAME OF GOD, HONESTY WILL SAVE YOU,” across the top of the cover page. Kam knows that the General appreciates this self-talk reminder right up front. Beneath it Kam titles this as the first part of his sworn confession and then signs his name. Someone will fill in the date later, because, though he does not know the date today, he also knows not to ask. The General’s men will fill in the location, for their own files. He writes the number one in the top left corner.

But which story should he tell?

The General said it was to be his masterpiece. Perhaps the best of each, he thinks. Though not Scandi crime. If this is to be the last thing he writes, it cannot be as a Swede, because he fucking hates Sweden. He would also like to write something the General will let him finish. He would like to reach the end.

The end.

Across hundreds of drafts, no matter the type of story, Kam has only managed to write one version of the end. It is the part he fears the most. Someday, he has told himself, someday he will write a new beginning to the bleakness of the end. Will he find it here, on this last attempt? A prisoner can dream, he thinks.

As always, Kam completes a final ritual before he starts this draft.

He imagines writing down his last remaining secret, in crayon, on one of these A4 sheets right in front of him.

One secret.

Three years in captivity, Kam has held on to only one.

Then he pictures a wooden cigar box. He slides the paper with the secret inside. In the early days of his captivity, he locked the real secret written on imaginary paper in the imaginary cigar box into an imaginary safe, but the General’s men broke into every physical safe in his apartment, and Kam thought he should also improve his mental defenses. He now pictures the cigar box with his secret incinerated on a monstrous pyre, the light and heat so fierce that every dark corner of his brain burns bright as day. This way Kam’s not lying when the General asks him if he’s been truthful. If the story is complete. He’s written it all down, has he not? The prisoner cannot be held responsible for how management handles the papers.

Kam presses the crayon to the paper and begins.

CHAPTER 1

Tehran, IranFour years ago

MYA NCESTORS BEGAN their journey to Persia as slaves. We left as dentists.

Though it must be said, General, that dentistry is its own form of slavery, even if its entanglements are more benign. When I returned to Iran, I was still a dentist, but it was really more of a cover. I had high hopes of making myself something more.

—

THE NIGHT BEFORE I conspired in a kidnapping was nine months to the day before I was kidnapped myself. Though, General, regarding the latter, I know that you prefer the term apprehended.

That evening I swung into the bedroom of the hotel suite, three glasses of Mr. Chavez Blended Special Whisky in hand. Anahita stood to fetch her clothes while Amir-Ali lit his pipe. He was sprawled across the bed, and the sheets were stretched across his chest, the rest of him uncovered and hairy. Anahita was what the mullahs called a “special” woman, or temporary wife. She was Amir-Ali’s favorite, and we were celebrating because it was his birthday. We were also blowing off some steam because the next day we had to help with the kidnapping. It wasn’t our first time, but still: It’s kidnapping. In the run-up it can be hard to think about anything else.

Amir-Ali made no move for the drink, so I stood there, glasses in hand, watching Anahita sort through the pile of her discarded clothes. She moved slowly, seemingly disinterested in putting them back on. Amir-Ali took a long drag of opium. The habit is far more common among older men in the countryside, but my friend was a passionate collector of all vice, no matter how alien. I distributed the whiskey. Amir-Ali pronounced it Iraqi piss, though he still downed half of it in the first gulp.

I took a seat in one of the chairs by the bed. Anahita, apparently deciding against the clothes, joined me, taking a seat in the facing chair. She crossed her legs and gave me a look laced with suggestion and mischief, the sort of practiced stare that had doubtless prompted many men to lose small fortunes. I might have, too, if I’d had one. Chip in on a few more kidnappings, and I’d be on my way.

“A mullah finishes a sermon on the merits of good hijab,” I said, forcing myself to look Anahita in the eyes. “Covering your head is a badge of honor. A sign of your obedience to Allah. On and on. It’s a long sermon.”

Amir-Ali put his head back on the pillow and shut his eyes with a snort. He always liked this one.

I continued, “After the sermon, a woman runs up to the mullah and says, I’m so pious, I even wear the hijab inside my own home. How will I be rewarded? And the mullah tells the woman that the keys to Paradise are yours. And right behind this woman there is another.”

“Of course there is,” Anahita cooed.

“And this second woman says to the mullah, Sir, I wear the chador. I even wear it in my own home. I wear it to sleep. And the mullah says that she will also be given the keys to Paradise.”

“Is there a third woman, my friend?” Amir-Ali asked, momentarily lost behind a cloud of smoke.

“There is a third woman,” I said. “She is last in line to speak with the mullah. And she says, Sir, I don’t bother with any of it. When I’m at home I strut around naked. And the mullah says, Madam, here are the keys to my house!”

Amir-Ali belly-laughed, sending more smoke our way. Anahita was also laughing as she stood up, stretching provocatively. This time I could not look away. Catching my eyes, she grinned: “I like the last woman.”

There was a rough knock on the hotel room door.

The kind of knock that in Tehran immediately has you thinking about where the exits are. “Guidance Patrol, open up.” The voice was gruff.

We all looked at each other. The Hanna was a favorite haunt in Tehran. We’d given the usual “tip” to the guy at the front desk and shown him the temporary marriage certificate to allow us upstairs with Anahita in tow, no problems. So what was this?

“Guidance Patrol,” Amir-Ali muttered. “What the hell are they doing here? They’re supposed to be on the streets.”

“Maybe someone downstairs reported us,” Anahita whispered.

I offered a bewildered shrug. Amir-Ali began hiding the pipe. Anahita hurriedly pulled on her clothes. I flung open a window to help with the smell and then hustled to the door. “Yes?” I asked.

“Open the door now!”

I did as the voice asked and was greeted by two men wearing the dark green uniforms and black berets of the Guidance Patrol. They were staring, wide-eyed, at Anahita, who’d drifted into the living room behind me. “What’s going on?” I demanded.

“Who is this?” the smaller guy said, jerking his chin toward Anahita. His wispy beard and baby face made the uniform seem absurd.

Amir-Ali, clothed but reeking of opium, came to the door and assumed his power stance. “She is my wife,” Amir-Ali said.

Oh boy, I thought.

“And who are you?” the smaller officer demanded.

“I am a surgeon,” Amir-Ali said. “Here—” He pulled out a business card and his ID and waved them in front of the taller guard’s stubbly face. “Have a look at this. My name is Amir-Ali Mirbaghri. Doctor Amir-Ali Mirbaghri.

“Mirbaghri . . .

“Mirbaghri!”

He just kept on repeating his name, hoping it would register, because one of his brothers was a bigwig in the Interior Ministry, to which the Guidance Patrol reported. Another brother did something inside the Central Bank. The third was a judge. His sister had married an up-and-comer in Tehran’s mayoralty. Amir-Ali, after losing his medical license, had been trying to make money for this well-known clan—times had been tough as of late—but the downside of his backstage role was that these two Guidance Patrol goons had no clue who he was.

“Let’s have your IDs,” the tall officer said to me and Anahita. The two officers studied the papers and then the tall one studied me. “You are a Jew, yes? This name isn’t Jewish”—he smacked my national card—“but there is something about you . . . I don’t know. I can feel it.”

Before I could respond, the small guy was waving documents at Amir-Ali: “You said you are married. Yet this woman doesn’t have your name.”

“Sigheh marriage,” Amir-Ali said smugly. “Just for tonight.”

The drink and opium had made my friend forget that it was my name on the temporary marriage certificate, not his. The drugs had also apparently convinced Amir-Ali that he had the certificate in his jacket pocket. He patted for a while and then turned sheepishly to me. Anahita put her face in her palms. From my own pocket I removed the forged certificate and then handed it to the tall guy. One look at the names, and he bared his teeth into a nasty smile while handing the paper to his comrade.

“Well, well,” he said, leering at Anahita. “Hello, Mrs. Whore.”

The short guy took a threatening step toward Amir-Ali and tore the certificate to shreds right in front of his face. Then he looked around at each of us. “A Jew, a whore, and an opium addict.”

An opening to a bad joke. And, unfortunately, true.

“A shameless breach of public morals,” the tall one snarled, glancing at Anahita, then forlornly into the bedroom, like a man left out.

“He’s not a Zionist,” Amir-Ali said, gripping me resolutely by the shoulder. “He’s not even really a Jew.” Apparently, my friend believed this to be the most serious of the three labels, the one to nail down first. I did wonder where his rebuttal was going, but he never got the chance to explain. The short guy, who had wandered into the bedroom, now returned along with the handle of whiskey and a triumphant smile. Alcohol meant not only fines or jail time, but lashings.

Amir-Ali was shouting that this was a quiet evening of backgammon among friends, what the hell was going on anyhow, and didn’t they know who he was? They responded by way of bagging his head. They cuffed me and Anahita, and before they could get the hoods on us, I caught a glance of her stoic face. She’d been arrested before, she knew the drill. And then she disappeared as one of the officers slipped a hood on me. In the darkness I heard Amir-Ali droning on about the backgammon. Then it was light again, and the taller guard was tossing my hood to the floor before yanking off Amir-Ali’s.

“Backgammon, you say?” he asked. “Show me the board. Who was playing?”

I wasn’t sure whether to laugh or cry. Amir-Ali looked to me. I don’t know what my eyes must have said, so I murmured, “Second drawer down, under the TV.”

The tall officer bulled across the room and retrieved the board that the hotel kept there. “Why is it in a drawer, then?”

Anahita’s chin drooped to her neck. She made a strange noise.

“We finished playing before you knocked,” Amir-Ali said, with the confidence of a practiced liar. “Just a few minutes ago, in fact.”

The tall guy ran a hand across the case. What he saw on his palm made him smile. He made a fist and brought it close to Amir-Ali’s face. My friend’s nose twitched, from fear or irritation, I did not know. The officer unfurled his hand and blew a cloud of dust into Amir-Ali’s eyes.

CHAPTER 2

Tehran

WE RODE IN hooded darkness and silence broken only by Amir-Ali’s occasional protestations. We couldn’t see where we were, but after maybe a half-hour ride in a Guidance Patrol van, Anahita was separated from us, and we were hustled into a building that smelled of dust and ancient photocopiers. When the hoods finally came off, Amir-Ali and I were in a windowless room, seated across the table from the two officers. On it was a regulation one-meter-long leather whip and a Quran. Something inside a large bucket on the floor had caught the short guy’s attention. I peered over and saw the bucket was teeming with cockroaches.

“What the fuck is this?” Amir-Ali said. He was also looking at the bucket.

“If we properly arrest and try you,” the tall officer said, “you’ll be given ninety-nine lashes apiece for the drinking. Guaranteed. The judge will sort out the fornication.”

“What about my wife?” Amir-Ali said. I was proud of my friend. Stick to your guns, I thought. Good for you.

“Your whore,” the short one said, “will be dealt with separately.”

“But why have it all processed formally?” the tall guy said, then he smiled at the roach bucket. “Let’s instead do fifty lashes and you each stick your head in that bucket for a few minutes.”

Amir-Ali looked at the whip and the bucket and then the tall guy. “Are you serious?”

“Where’s Anahita?” I heard myself say.

“The whore is elsewhere,” the short one said.

“How much do you want for a tip?” Amir-Ali said. “Let’s settle this and be done.”

The short one leaned forward and said, “You’re in too deep for that. This is beyond money.”

“Beyond money,” Amir-Ali shouted incredulously. “Are you insane?”

They did look insane, I must admit. They looked like a couple guys who were going to have a hell of a time flogging us.

Amir-Ali’s desperation sharpened to anger: “If you want to play it this way, you’re both going to lose your jobs. You think I was inventing my brother at the Interior Ministry? And then, once you’re on the street, I’m going to find you and take your balls. You are making a huge mistake. So how about this: You let us go, plus the girl, and you keep your balls, eh? I have ways of getting to you people.”

The officers, undeterred and tiring of Amir-Ali’s threats, decided that he’d volunteered to go first. But, perhaps a bit queasy about the prospect of jamming a man’s head into a writhing mass of insects, the tall officer picked up the whip and tucked the Quran into his armpit.

The short one stood Amir-Ali up, stripped off his shirt, and made him kneel, facing the wall. I sat there, frozen, as he begged for mercy at the top of his lungs.

“Fifty lashes,” the tall one pronounced. “Half-price.” And now Amir-Ali was hollering about lawyers and judges and the tall one was saying that’s the point, we’re going to save the lawyers and judges the trouble. I was so entranced I didn’t even hear the cell door open. A woman in a black chador swept by me. She took a position between the officers, right behind Amir-Ali, who had not stopped shouting. The woman raised a leg to expose her studded Valentino heels. She stuck one into Amir-Ali’s upper back, as if requiring leverage for the flogging to come. She withdrew something, pink and poufy, from inside her chador.

“This is for your corruption,” the tall one said. “For your sins, Amir-Ali Mirbaghri.”

The woman lashed her poufy whip across Amir-Ali’s back. He was tense, twitching, waiting for pain that never did come. “One,” she said, imitating the low voice of a man. Then she dangled the whip over his head so the pink poufs bounced through his field of vision.

“Happy birthday,” I cried out. I stood and smacked Amir-Ali’s bare back. “Happy birthday, you sinner. You sower of corruption on earth.”

The two officers also laughed.

Anahita laughed. Amir-Ali spun around, looked at me, then up at Anahita in disbelief. He laughed, at first in relief, then in joy. Pure joy.

Back then, before all that was to come, I could laugh at such things. The maw of your Islamic Republic chewed up other people, not us. Jokes and sporting fun are possible at such a distance. No longer, of course. But that night none of us stopped laughing for a very long time.

—

WE ALL WENT BACK to Amir-Ali’s place and kept the party going, though this time, with Anahita in the car, we kept our eyes peeled for the actual Guidance Patrol. We all had whiskeys in Amir-Ali’s garden, and I settled up with the two guys while Amir-Ali and Anahita retreated for another romp in the bedroom. They were wannabe actors, currently employed at my favorite bakery, probably homosexuals, and I told them—quite honestly—that I thought they had great potential. Two gay bakers had managed to impersonate the fanatical floggers of the Guidance Patrol. “Great things,” I told them. “I foresee great things for you.”

Near dawn, after we’d bidden Anahita farewell, Amir-Ali filled our glasses once more and said he had something to show me. We went out through his courtyard, the trees covered in a thin layer of Tehran’s smog brought low as dust. In his garage he flicked on the lights and I saw that he was beaming.

I whistled and jokingly smacked his shoulder. “You shouldn’t have.”

He laughed, running his hand over the silver hood. He thunked open the driver’s door. “A gift to myself.”

“It’s beautiful,” I said. And it was. The coachline was a delicate blue, there were four proud rear exhausts, its shoulder line was sharp and well-defined, and the rear lamps, I saw, floated in the visual trickery of a transparent panel. Like Mirbaghri himself, with his scattered streaks of gray hair, the car sported only the gentlest whispers of patina: wrinkled, faded leather on the seats, a few places where the light glinted off the imperfections of dents. But mostly it was a thing of beauty.

“It’s a Khamsin,” Mirbaghri said, sitting in the front seat like a little boy, “ ’72.”

“Khamsin,” I said, letting the name gently roll off my tongue.

Amir-Ali smiled. “Named for an Egyptian desert wind. Guess who owned it.”

“The Ayatollah,” I said immediately, and with confidence. “He drove it to the airport in Paris on his way to Tehran. I’ve seen the videos.”

Mirbaghri’s confusion melted into a long laugh when he caught a glimpse of my eyes. I bent down for a better look inside. The interior was all blue. The dash was edged in blue leather and trimmed in gray. Below was an absolute riot of switches, slide controls, vents, and knobs that resembled the cockpit inside an Apollo space capsule.

He brought the engine to life. It was throaty; a deep, sonorous hum.

“This was part of the Shah’s imperial garage,” Mirbaghri said, his hands caressing the steering wheel. “The headlights pop up. Hydraulics. Look.”

He flipped them up. The beams brightened the white stone walls of the garage.

“Are we going for a ride?” I asked.

“I’m too drunk,” he said, quite sadly, and killed the engine. “It’s a bitch to drive here in the city. But on an open road? Paradise.”

“You should be saving your cash,” I said. “What would Glitzman say?”

“He’d scold me, too. He’d ask how anyone would think a failed doctor could afford such a thing.”

“And?”

“I’m too alive for this place,” Amir-Ali said, his hand stroking the wheel. “You’ve got your California dream. I’ve got right now.”

“What you’ve got is a problem holding on to money,” I said.

With a chuckle he wrapped his palm around the stick. “First you channel Glitzman, now my maman. Shame on you. Plus, once you buy a place in California, why would I need to? I’ll just sleep on your couch when I visit. How close are you to the number?”

“Two more years,” I said. “Give or take.”

We exchanged a quick glance that said, If we make it, and we broke eye contact because that was a grim and pointless subject, and why spoil the afterglow of a fine evening?

Amir-Ali whistled, rapped his fingers on the wheel, and lurched unsteadily out of the car. “Let’s go inside for some tea. Sober up and toast the morning. We’ve got a big day.” I helped him stand, and took a good long look at the Khamsin, though it was really more of a leer. A fantasy gripped me: I am driving this car, southbound along the Pacific Coast Highway. The windows are down. The air is silky, the palms stooped and proud all at once. Dusk burns orange and pink and the sea is glass. There is a woman beside me, faceless as she is beautiful. I am listening to the engine’s mellow voice, the road and its possibilities opening before me.

With a chuckle at my obvious lust, Amir-Ali killed the garage lights.

—

IN THE KITCHEN I put water on for tea and camped at the counter with my phone. I clicked into my calculator app, the one Glitzman’s people had loaded onto my phone during our training in Albania the previous year. I entered a seventeen-digit alphanumeric code which opened the partitioned hard drive.

“What does Glitzman have to say?” Amir-Ali asked, laying out a spread of flatbread, white cheese, and jam.

I read the short message. “We’re on,” I said, thinking I’d have to pass on the tea because there were threads of nausea coiling in my throat.

As if mirroring my thoughts, the kettle began to scream.

CHAPTER 3

Tehran

THE MORNING OF THE KIDNAPPING, the weather was so pleasant, Tehran’s usually smoggy skies so clear and open to the mountains, that after cleaning up at home I decided on a leisurely walk to my dental practice.

I often consider Tehran my foster home because it has kicked me around so much. But the analogy doesn’t quite work because I was actually born here. It is my native home, even if I am a Persian Jew raised in Sweden, and even if by that sunny morning ten thousand American dollars were flowing monthly to an escrow account established by a maze of shell companies created by the State of Israel.

And, quite honestly, Tehran is more alive than any home I’ve ever known.

It is hewn into the mountains, obnoxiously loud, and covered by a jagged skin of brutalist buildings. It smells of smoke and diesel. Developed haphazardly, growing in disorganized spurts, Tehran, like most of us, lacks any coherent center. And like us, it is also unpredictable. That morning I hoped the city would behave otherwise. That things would go to plan.

The breeze meant the smell of diesel and dust was instead baking bread, ripe fruit, and dried herbs piled in stall baskets. I passed a Super Star Fried Chicken and then crossed under one of the government-funded billboards urging Tehran’s bitchy citizens to stop bitching so much. This one read: let’s not spend so much time discussing society’s problems in our homes. But where else, really, could we complain? Not out here in the street, that’s for sure.

The buildings around my practice were that classic Tehrani jumble of concrete slabs, gaudy marble, and the occasional faux-Grecian pillars. My office was the concrete slab varietal, enlivened by a few scrawny sycamores that stood sentry along the sidewalk. Amir-Ali was working on a cigarette outside.

We went in and headed straight for the storage room. It was Friday, first day of the weekend, and the place was empty.

During one of our meetings in Sweden, before I’d opened the practice in Tehran, I’d drawn the proposed office layout on a napkin, and Glitzman had asked where the storage room would be, and how large. What size crates might it hold? What, he asked, would you say is the capacity? And I’d pointed to where we might install supply closets and he’d shaken his head and said that won’t do at all.

And so exam room three had become storage space. None of my employees had the key. I unlocked the room and we went inside and shut the door behind us. On the floor were a dozen or so boxes that had arrived in recent weeks. All were covered in shipping labels denoting European points of origin (Brussels, Paris, Frankfurt) and if anyone had bothered to investigate the sender, they would have found them to be dental suppliers with legitimate, if rather sparse, websites. Some of the packages had been delivered through the actual post. Others by unmarked vans at strange hours near an industrial park on the eastern rim of Tehran, where either I or Amir-Ali would duly collect them. I’d invented alibis for what might be inside based on the shape and weight, imagining conversations with a curious hygienist who might spot them, or, worse, with a nosy inspector arriving to make trouble for a bribe. Oh yes, sir, that bulky one there is a stool. That smaller one is a new chair-mounted kit for exam room two, here, I can show you, yes, the one in there is getting old . . .

As I peeled open the flap of the first box, I saw the glint of gunmetal and that nausea again began to climb my throat. I wasn’t exactly thrilled to be part of anything kinetic, to use a term Glitzman was fond of. Amir-Ali peered over my shoulder and whistled. There were five guns packed tightly inside. AK-47s or some variant.

In another box we found the banana-shaped magazines, hidden in individual brown packaging. There was a satellite phone in another. A case with vials of a clear liquid and syringes. Handguns. Another box with the magazines. Four cattle prods. Three sets of license plates with Tehrani registration. I did appreciate that they were pre-weathered, splattered in mud. There were three first-aid kits. A box of push-to-talks. A Toughbook laptop. Body armor. An assortment of duffel bags and a Pelican case. Microphones. Three webcams. Following the instructions in Glitzman’s cable, we packed everything up and then locked the storage room.

Both of us wanted a smoke, but Glitzman had told us not to loiter around outside, so we went into my office, where I had an ample supply of duty-free Swedish snus, and dipped while we waited. Stuffing one of the packets against my gums, I looked at Amir-Ali and could tell we were thinking the same thing.

We should have asked Glitzman for a raise.

—

THE OFFICE LINE RANG a few minutes later. When I picked it up I heard three clicks.

Amir-Ali and I went downstairs into the parking garage. The opening roller door slowly revealed an idling gray van, which clipped inside soon as it could, parking near the white Toyota van and the Peugeot sedan that Amir-Ali and I had bought two weeks earlier at Glitzman’s behest, in cash, from a smuggler out in Kerman.

Two Israeli women I did not know hopped out, both cloaked in chadors. I pegged them for Persian Jews, like me. They gave us aliases; only later would I learn their true names and scraps of their biographies. The short one with gunfighter eyes was Rivka Sadegh; she was Glitzman’s favorite, a bruiser, a Persian Jew of the self-loathing varietal. The tall woman, lean and beautiful with cheekbones high as heaven, was Yael. Next came her husband, Meir, who would ride with me and, I presumed, manage the eventual interrogation once our target, one Captain Ismail Qaani, fell into our grip.

The two Kurdish brothers in the front seat had trained with me and Amir-Ali in Albania.

Aryas, the driver, greeted me with his typical serious demeanor twinged with bitterness—scar of having recently lost the love of his life to another man back in Erbil. Unbuckling his seat belt, he stepped down from the van. I handed him keys for the Toyota that Amir-Ali and I had secured.

Kovan, his brother, was not one for seat belts. He was thick, in the transitional decade where he was no longer muscular, but not yet truly fat. When we opened the back of the van to toss in one of the Pelican cases, Kovan snickered when I startled at the sight of a dead goat wrapped in plastic. Kovan was a man who took pleasure in others’ discomfort— the sort who relish eating sandwiches in front of the family dog, or who don’t warn you about dead goats in the backseat.

Glitzman, finished barking in Hebrew over a satphone in the van, now jumped out and greeted us.

Glitzman. What to say of Arik Glitzman, the man who recruited me? By then I’d come to learn that he was Chief of Mossad’s Caesarea Division, the group responsible for sowing chaos and mayhem in Iran.

Glitzman was rather Napoleonic, short and paunchy with a thatch of black hair and a round face bright with a wide smile. There was fun in his eyes and if they had not belonged to a secret servant of the State of Israel, they might have belonged to a magician, or a kindergarten teacher. Nothing in his mouth was really straight; his front teeth, the implants, were blazing white, while the rest were quite stained. I had assumed the implants to be the result of an accident, perhaps a tumble down the stairs, and only later would I learn I was half right: it had been stairs, but he’d been pushed. Also the stairs had been in Dubai.

“You feel good?” he asked. Though we had everything planned, Glitz-man was fond of looking his assets—people like me and Amir-Ali—in the eyes before a collective leap off the cliff.

“I feel good,” Amir-Ali said, putting on his body armor.

“And you?” Glitzman asked. “All good?”

“I feel how I feel,” I said.

“And how is that?”

“Ready to get on with it.”

“Are you going to be okay?”

“I’ll be fine,” I said. “But I’d like to know why we’re after him.”

“What’s the point of you knowing?”

“I’ll feel better.”

Glitzman gave me a piteous look bleeding to anger. “That’s what the money is for. Keep your eye on the work, and soon enough you’ll have your waves and sun and surfer girls. Let me keep it simple for you. I’ll handle the questions.” He’d begun smiling, but it was one I did not like.

“Something,” I said. “Give me something, Arik.” I unzipped my jacket to slide on my body armor.

“Something would be nice,” Amir-Ali said, “for a change.”

For a moment Glitzman watched the two women inspect the cattle prods. At the zap of electricity he turned to us and said, “Captain Ismail Qaani, as you know, is a member of the Qods Force. A new group called Unit 840. It’s run by a colonel named Ghorbani. His unit is out to kill Jews. I’m out to stop him.”

Glitzman walked us a few paces away from the van while the team loaded the gear. His arm was on my shoulder, and he spoke to both of us with the intensity he can muster for conversations when he wants you to believe there’s no one else in the world but you and him. “Captain Qaani has been tasked with supporting operations to kill Jews in Turkey and Europe. And we’d like to ask him a few questions about that.”

“How do you know?” I replied, and immediately wished I hadn’t. Glitzman treated me to a look of sadness bordering on condescension.

“Special collection,” he said, and hit my shoulder, flashing that same unkind smile.

All of us huddled briefly around the vans, and we went through it all once more. Meir ran a final check to confirm that the feeds from the cameras hidden in the blue Peugeot were linked to the Toughbook that Glitzman would operate from the back of the Toyota. I was going to drive the Peugeot, Meir my passenger. Our job was to pull off the road right by the patch of scrub in the roundabout, the one I’d been studying so intently that it had begun appearing in my dreams.

As we finished loading everything, I caught a final glimpse of goat hooves entombed in plastic. Glitzman, monitoring the target’s phone from a tablet he’d brought with him, barked that it was time.

The three engines kicked to life. Meir and I went first, in the Peugeot laden with hidden cameras. Amir-Ali drove the gray van, Kovan beside him, the two Israeli women wearing chadors and sporting cattle prods behind, alongside the goat carcass, a couple buckets of blood, and most of the guns. Aryas drove the Toyota with Glitzman and his command center, link to unseen masters in Tel Aviv, hidden in back. We clipped out of my parking garage and set off to kidnap a bad man bound for a pleasant weekend with his family in the countryside. A few more of these, and soon enough I’d be trading the thrilling anxiety of espionage and the tedium of dentistry for the warmth of the California sun.

My midlife crisis was shaping up nicely, I thought.

CHAPTER 4

Tehran / Absard

THE JOURNEY TO ABSARD wove through a landscape of brown-green hills and mountains, some wrinkled and naked, others thatched with scrubby bushes and trees. Wispy clouds scudded along an otherwise brilliant blue sky, untainted by smog, and I imagined Glitzman pronouncing the weather perfect for a kidnapping. Not a single reason for Qaani to stay in his car, he would say, or something like it. Traffic was light, mostly families on their way to weekend picnics or hikes, and I was glad no one I passed paid us much mind, because I was white-knuckled and sweaty for most of the ride, feeling that if anyone looked me up and down they’d have reasons to think I’d just fled some gruesome crime scene back in the capital. Wrong, I thought (and even then the thought felt insane). I’m going to the crime scene, not coming from it.

Meir and I did not exchange more than a few words but there was a softness to him, a candle of amusement brightening his face, and in less awful circumstances we’d have found much to share. While I drove, in his flawless Persian Meir occasionally mumbled shreds of Rūmī and Hafez, the poets my mother had read to me when I was very young. Meir ejected each verse with his arms pretzeled across his chest, searching the scrubby hills and passing orchards for enemies that never did show themselves.

The drive took ninety minutes. It felt like a thousand. I spent a lot of it thinking about Captain Qaani, who at this point I knew well from the surveillance package we had assembled over the past few months. He was a workaholic, but at home he was affectionate and attentive to his family. He had two younger brothers and their WhatsApp thread was full of what I found to be genuinely hilarious ribbing and fraternal comradery. He despised Israel, Zionism, and, more particularly, Jews. According to Glitzman’s special collection he was working feverishly to kill more of us.

Captain Qaani also liked to take his wife and two sons to their home in Absard for the weekends. He was not senior enough for a bodyguard or security detail, and, critically, Qaani liked to drive himself. The family always took the same route.

All along this route Aryas and Glitzman had duly—and clandestinely—followed, keeping the vehicle in sight the entire way. Meir and I stayed well ahead, out of view.

Outside Absard I pulled the Peugeot onto a patch of dirt at the far end of a roundabout the Qaanis would whirl through in . . . I checked the time . . . an hour. Maybe an hour fifteen depending on bladders. I positioned the car so the cameras snuggled into the left rear brake light, headrest, and dash would have clean views of the road. Meir clicked the push-to-talk three times and received three in return.