5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

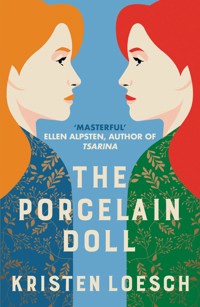

'A masterful debut' - Ellen Alpsten, author of Tsarina In a faraway kingdom, in a long-ago land ... Rosie's only inheritance from her reclusive mother is a notebook full of handwritten fairy tales. But another story is lurking between the lines. Desperate for answers to questions that have tormented her for years, Rosie travels to Moscow and uncovers a devastating family history spanning the 1917 Revolution, Stalin's bloody purges and beyond. At the heart of those answers stands a young noblewoman, as pretty as a porcelain doll, whose actions reverberate across the century .

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 491

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THE PORCELAIN DOLL

Kristen Loesch

For my family

So few roads were travelled So many mistakes were made

sergey yesenin

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

In some faraway kingdom, in some long-ago land, there lived a young girl who looked just like her porcelain doll. The same rusty-gold hair. The same dark-wine eyes. The girl’s own mother could hardly tell them apart. But they were never apart, for the girl always held the doll at her side, to keep it from the clutches of her many, many siblings.

The family lived in a dusky-pink house by the river, and in the evenings, the children liked to gather around the old stove and listen to their mother tell stories. Stories of kingdoms even further away and lands even longer ago, when there had been kings and queens living in castles; stories of how those castles had been swept away into the midnight-black sea. The many, many siblings would drift away to sleep on these stories, and then the mother would take the girl and the doll into her lap and tell tales of the girl’s father. He’d had the same rusty-gold hair, the same dark-wine eyes, in some other faraway kingdom, in some other long-ago land.

But one evening after supper, as the stove simmered and the samovar sang and the mother spoke and the children listened, there came the sound of footsteps outside the house. Stomp-stomp-stomp.

There came a knock on the dusky-pink door. Rap-rap-rap.

There came a man’s voice, which had no colour at all. Open, open, open!

The mother opened the door. Two men stood there, each carrying rifles.

‘You will come with us,’ said the men to the mother.

The mother hung her head so that her children could not see her cry. But the samovar ceased to sing and the stove ceased to simmer and the story stayed untold, and in the silence, the many, many siblings could hear their mother’s tears fall to the ground. They ran to stop the men.

Stop-stop-stop!

Bang-bang-bang.

The siblings fell like their mother’s tears. Their bodies lay as quiet and as still as the doll that the girl held.

‘Is that another one?’ said one of the men to the other, pointing to the girl, who had remained by the stove.

‘Those are just dolls,’ said the other man to the first.

The men took the mother with them. Their footsteps began to fade. Stomp-stomp-sto … The mother’s cries seemed far away and long ago. No, no, no … The girl began to breathe again. In, out, in. She stood, with her doll beneath her arm, and she walked, across the blood-red floor, over her blood-red siblings, through the blood-red door, out of the blood-red house, all the way to the blood-red river. She forgot to wash her blood-red hands.

For fear of those men, the girl did not stay at the river, nor did she stay in that land. For fear of those men, through all her years, along all her journeys, she carried her doll. But she carried it too long, so long that she could not tell the two of them apart any more either. So long that she could not be sure if she was the girl at all; if she was the one who was real.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

Rosie

London, June 1991

The man I’ve come to see is nearly a century old. White-haired and lean, with just a dash of his youthful film-star looks remaining, he sits alone onstage, drumming his fingers on his knees. His head is tilted back as he takes a hard look at the crowd, at the latecomers standing awkwardly in the aisles, their smiles sheepish. At the young couple who have brought their children, a toddler girl swinging her legs back and forth, and the older one, a boy, solemn-faced and motionless. At me.

Usually when two strangers make eye contact across a crowded room, one or both will look away, but neither of us do.

Alexey Ivanov will be reading tonight from his memoir, the slim, red-jacketed book sitting on a table next to his chair. I’ve read it so many times by now that I could mouth it alongside him: A hillside falls out of view, and voices, too, fall away … we are like castaways, adrift on a single piece of wreckage that is floating to sea, leaving behind everything that linked us to humanity …

Alexey stands up. ‘Thank you all for coming,’ he says, with the knife-edge of an accent. ‘And so I begin.’

The Last Bolshevik is an account of his time on Stalin’s White Sea Canal, told in short-story form so that people don’t forget to breathe as they’re reading it. Today Alexey has chosen the tale of a work party’s doomed expedition through a grim, wintry wilderness to build a road that no one would ever take. The holes that the prisoners dug were for themselves. It would be their only grave …

My hands feel clammy and heavy, and my toes begin to tingle in my boots. The middle-aged man seated next to me pulls his coat tighter around himself, while just up ahead, the young girl has stopped swinging her legs and is as straight-backed as her older brother.

In a lecture hall full of people, Alexey Ivanov has snuffed out every sound.

He reaches the end of the story and closes the book. ‘I am open to questions,’ he says.

There’s a faint shuffling of feet. Somewhere in the back, someone coughs and a baby begins to fuss. A quick shushing by the mother follows. Alexey is preparing to settle back into his chair when the man next to me suddenly lifts a hand.

Alexey smiles broadly and gestures to the man. ‘Go on.’

‘My question is a wee bit personal,’ says my neighbour, in a thick Scottish brogue. He shifts in his seat. ‘I hope you don’t mind …’

‘Please.’

‘You dedicated this memoir to someone you only call “Kukolka”. Is there any chance you will share with us who that really was?’

The smile slides off Alexey Ivanov’s face. Without it he no longer looks like the famous dissident writer, the celebrated historian. He’s only an old man, stooping beneath the burden of over nine decades of life. He glances around the room once more, just as the baby, somewhere out there, lets out another startled cry.

Alexey’s gaze lands on me again for half a second before moving on.

‘Hers is a name I never speak aloud,’ he says. ‘And if I did, I would shout it.’

I leave my row and head for the stage. The audience is filtering out, but Alexey is still shaking hands, chatting with the organisers. I’ve read all his writing, mostly while hunched over in a reading room in the Bodleian, and this is the effect of those musty hours, that pure silence: no matter how human the man might look, Alexey Ivanov has become almost a mythical figure to me. A legend.

‘Hello there,’ he says, turning to me. He has a smile like a torchlight.

‘I enjoyed your reading so much, Mr Ivanov,’ I say, finding my voice. Maybe enjoy isn’t the right word, but he nods. ‘Your story is inspirational.’

I’d planned in advance to say this, but only after saying it do I realise how much I mean it.

‘Thank you,’ he says.

‘My name is Rosemary White. Rosie. I saw your advert in Oxford. I’m a postgraduate there.’ I cough. ‘You’re looking for a research assistant, for the summer?’

‘I am,’ he says pleasantly. ‘Someone who can join me in Moscow.’

I loosen my hold on my handbag. ‘I’d be interested to apply, if the position’s still open.’

‘It most certainly is.’

‘I don’t have much experience in your field, but I’m fluent in Russian and English—’

‘I’ll be in Oxford on Thursday,’ he says. ‘Why don’t we meet up? I’d be happy to tell you more about it.’

‘Absolutely, thank you. Only I’m leaving tomorrow for Yorkshire to visit my fiancé’s grandmother. She lives alone. We visit once a month.’ I’m not sure why I’m spewing information like this. ‘I’ll be back by the weekend.’

‘This weekend, then,’ he says. His voice is mild. All around us is nothing but people talking and bantering, a pleasing hum, but there is something in Alexey’s eyes that suddenly makes me want to brace against a biting wind. Maybe the excerpt he just read out, the details of the White Sea, those barren roads, those long winters, is still too fresh in my mind. Maybe it’s all people ever see, when they look at him.

It’s past my mother’s bedtime by the time I make it back to her apartment, but there’s a sound coming from her room, a low moan.

I knock on her door. ‘Mum? You awake?’

Another half-smothered noise.

I push the door open. Mum’s bedroom is filthy and gloomy, and she matches it perfectly. Unwashed, unmoving, she is sitting up in bed, slouched against her pillows, the musky scent of vodka rolling off her in waves. I drop in on her at least once a month, stay with her a night or two here in London. I’ve been visiting more frequently of late, but if anything, she seems to recognise me less. Mum carried on drinking even after the doctors said her liver was bound to fail, was failing, had failed. She’s drunk right now.

‘I was at a talk,’ I say. ‘Have you been waiting up?’

Her jaundiced eyes dart around the room before finding me right in front of her.

‘Well, goodnight then.’ I set the dosette boxes on her bedside table upright and wipe my hands on my slacks. ‘Do you want me to wake you in the morning?’ I pause. ‘I’m going up first thing to York, remember?’

She sucks in her bony cheeks and starts to grasp at her sheets for support. She wants me to come closer. I seat myself gingerly at the foot of the bed.

‘Raisa,’ she mumbles.

Raisa. My birth name. By now it feels more like a physical thing I left behind in Russia, along with my clothes, my books, everything else that made me, me. My mother is the only one who uses it.

When she dies, she’ll take it with her.

‘I know what you’re planning.’ Her breaths are staggered.

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

‘Yes, you do.’ Her gaze locks on mine, but she can’t maintain it. ‘You’ve been trying to get to Moscow.’

‘How do you—’

‘I’ve overheard you on the telephone with the embassy. Why do they keep denying you? Is it because of what you study?’ She tries to laugh. ‘I hope they never let you through.’

‘It’s because of the hash you made of the paperwork when we moved here,’ I say, bristling. ‘I’ve always wanted to return just once, to see it. I thought it’d be best to go before Richard and I get married. Get it done with.’

‘You’re lying, Raisochka. You’re going to look for that man.’

She must be drunker than she’s ever been, to mention that man. Fourteen years ago, as our rickety Aeroflot jet took off into a deep-crimson skyline, London-bound, I dared to ask her about him. Mum only stared straight ahead. That was her answer: There wasn’t any that man. I dreamt it. I might have dreamt all of it.

‘If you go away now, I won’t be here when you get back,’ she says.

‘Mum, please don’t talk like that. And if you would just let us—’

‘You mean let him. Him with his proper money. Thinks he’s better than me.’

‘What? Are you talking about Richard? Richard doesn’t think—’

‘The dolls.’ Her pupils dilate. ‘What do you plan to do with my dolls, may I ask, once I’m dead?’

I open my mouth and snap it shut. The vodka’s definitely talking now. Dolls? I’ve never once considered what I’ll do with her collection of old bisque porcelain dolls. They’re like an army of the undead, with their stiff faces, unseeing eyes. Luckily they’re stored on a shelf in the living room, or they’d be witness to this very conversation. To my wavering.

After she’s downed a few, Mum often sits and speaks to them.

‘I don’t know,’ I say, but she’s already nodded off.

At half eight in the morning, Mum is still asleep. Her face is slimy with sweat, but she appears so relaxed, so restful, that she might well have died overnight. I touch her wrist for her pulse, faint as a stain, and then reach over to her bedside table to fix the dosette boxes – she always knocks them over, groping for something to throw back – but the surface has been cleared. No boxes. No crumpled bills, either, and no bottles. All that lies there now is a leather-bound notebook.

It is open to a page as yellow as my mother.

I feel a burst of nerves as I lean over. The cursive Cyrillic writing is a tight, indecipherable scrawl. Handwritten font is nothing like the block letters of published Russian books or street signs. I am able to make out the first few lines:

A Note for the Reader

These stories should not be read in order.

‘Raisa?’

‘Mum,’ I say, with a jolt. ‘I was just looking at—what is this? You wrote down your stories?’

She claws for me, and I take her hand.

‘I …’ Something, maybe the bile from her liver, is so high in my mother’s throat that it cuts off her voice. ‘I … for you, Raisochka. Take with you. Read, please. Promise me.’

‘I promise. Let me get you some water, Mum.’ I try to pull away, but she’s the one holding my hand now. My palm against hers feels sticky.

‘I … sorry …’

I want to say sorry too. I’m sorry that I’m the one who ended up here with her. I’m sorry that she wasn’t able to leave me behind, because if she had, maybe she could have left that man behind too. But I’ve had too much practice not saying things aloud. I learnt that from Mum herself. I can’t unlearn it now. Everything that has ever gone unsaid hangs in the air between us, as thick as the smell of decay that emanates from the strange, small notebook.

Or perhaps from what is left of my mother.

‘Promise,’ she says again.

‘I promise.’

‘I love you, little sun.’ Her eyes close to a sliver. ‘Sleepy …’

‘Mum … ?’

She lets go of my hand, still murmuring to herself.

As the train pulls out of King’s Cross I rest my forehead against the glass. Richard is already in York. It’ll be a decent drive out to where his grandmother lives, in a cottage that sits, or floats, in the nothingness of the northern moors. It is where Richard and I will marry in autumn. Mum has never been there, but she’d love how it looks rugged and angry one day, winsome and windswept the next. Like a landscape from her stories.

I’ve got her notebook in my handbag now. I’ll keep my promise. But I’ve always hated her stories.

They’re the single thing about her to become more vivid and not less, after a tipple. Strange little vignettes, fairy tales in miniature, often with a nightmarish tint. They all start with some version of her favourite line: Far away and long ago. That line is not a coincidence. Most of my mother is far away and long ago.

As Charlotte shows us where the musicians will be set up and instructs us not to venture anywhere near her rose garden, with a slight huff, a chilly gust of air whisks past. I shudder, and Richard’s grandmother glances at me, her smile just as chilly.

‘Does it not suit?’ she asks.

‘No, it’s—it’s beautiful.’

Richard shrugs off his coat and puts it around my shoulders. We approach the house from the back. Charlotte’s dog, some ankle-high breed of terrier, is yapping by the door, jumping up and down on all fours like a mechanical toy. Charlotte’s lips are pressed together. Her dog is usually to be found on his living-room cushions, sniffing at a tray of treats. He is not the sort of dog who sneaks out on purpose. He isn’t what most people would even call a dog.

‘Have you slipped him some coffee?’ I joke to Richard. ‘Or some—’

Garlic.

The air is laced with the smell of garlic, carrying further than it otherwise might, perhaps, on that brisk wind. For a second I worry it might be me, having just spent the week at my mother’s, because Mum adds garlic to everything she consumes. Maybe even her drinks. As a teenager, I used to make snide comments: Was there a garlic shortage or something when you were a kid? And she’d laugh like I was being funny, and not like she was pissed.

I was not being funny.

‘Ro? You OK?’ asks Richard.

‘Is it the roses?’ enquires Charlotte. ‘Their scent is peaking.’

‘I’m just cold, I think.’

The dog is still howling and now sounds deranged.

‘I don’t know what could be the matter with him.’ Charlotte places a hand on the brooch pinned to her lapel. ‘Would you go around front, Richie? Someone might have come by.’

I shrink into Richard’s coat. Someone is already there, right there by the back entrance. A visitor who has drawn the rat-dog from his morning nap; who has likely been watching us meander through Charlotte’s garden. A visitor who is often there in Oxford too.

Zoya.

Richard walks off. The dog quiets down, appearing satisfied that the racket has got his message across.

‘I feel that there’s something amiss with you today, Rosie,’ says Charlotte. ‘You’re not altogether yourself.’ She makes a tch sound.

The sound is everything she thinks of me, rolled into a syllable. I don’t know if she envisioned her favourite grandchild ending up with someone like me, but she also probably reckons it could be worse. Tch, tch.

Another tch at me for not replying straightaway. I try to smile at her, but she doesn’t try in return. What does she want, an apology for not being myself? Who is the Rosie who is herself? Rosie, whose name has not always been Rosie? Sometimes there’s a glimmer in Charlotte that makes me wonder if she suspects something to be wrong with my story. But she’s the one who retreated into a remote, rose-growing widowhood far from everyone she knows, from her old married life. Maybe there’s something wrong with her story too.

‘It’s my mother. She’s—she’s unwell,’ I say.

Charlotte draws herself up. ‘Of course. Richard did say. How terribly difficult for your family. Is your mother religious?’

‘She has … her views,’ I say. ‘She believes in the soul.’

Mum was once determined to make me and Zoya believe in it too. She’d try to wear us down, evening after evening, sitting at our bedside, smoothing down that favourite nightgown of hers, the only thing she wears nowadays. Some of her claims about the human soul came with solid moral lessons. Others were bits and bobs of morbid superstition, what schoolkids might circulate in the playground.

I didn’t believe any of it then.

The dog is glacially silent now.

‘No one,’ reports Richard, strolling back towards us. ‘Shall we go in?’

Charlotte bends with impressive flexibility and scoops up her pet. His tail whacks like a metronome against her arm. Before I can follow, the smell of garlic wafts by again, mixed with that of vodka now. A potent combination.

The particular combination that comes off Mum like radioactivity.

My breakfast turns in my stomach, threatens to rise. According to Mum’s folklore, there is only one hard rule: after death, the soul must visit all the different places in which the living person has ever sinned.

Didn’t Zoya commit sins anywhere other than right behind me?

Mum’s neighbour rings from London late in the evening. Mum has died. He brought in her shopping as usual and he could just tell, he says. I want to ask him to check again because Mum’s been passing for dead for a few years now, but I don’t. I crawl into bed and I think about this tiny ivy-slathered house and the moorland all around, wild and empty, extending in every direction, coming from nowhere, belonging to no one.

Moors. Moored. Unmoored.

Back in London, there is no funeral, no ceremony beyond the cremation. Mum had no friends. She didn’t know anyone who wasn’t being paid to know her back. I take her ashes with me in a nondescript urn and I decline Richard’s offer to stay behind to help.

I’ll only be an extra day, I say, because I have to be in Oxford by the weekend.

I try to tidy up her apartment. I start in the kitchen, with her grisly jars of home-pickled vegetables, not one of which I have ever seen her touch. I have a go at the living room next, but the glass eyes of her dolls follow me around like they’re waiting for me to turn my back – so I decide to deal with them next time and I open all the windows instead, to let some of the stale, vodka-soaked air out. To let Mum’s soul out.

I just have no idea what to do with what’s left. Should I put the urn in storage? Or on display?

If I were going to scatter her ashes, it ought to be off the stage at the Bolshoi, over the musicians’ heads, as bravas ring out from every box. Mum was in the corps de ballet before getting married – before my sister and I came along, obliterating any chance she had of being promoted to principal – and she probably always hoped to die onstage, mid-plié. Zoya and I used to tease her as she practised in the mornings. We’d fall over our own feet trying to go en pointe alongside her.

Katerina Ballerina.

Later I swing by to meet her solicitor. He has a smart office and a sympathetic smile. He tells me she’s left me the apartment. It’s mine now. That can’t be right, I say, trying to argue with him. Richard and I have been paying rent on it. We send her a cheque every three months.

I have the mental image of cheques being stashed away, pickled in jars.

Her solicitor feels sorry for me. I can hear it in his voice. He has a posh accent, like Richard’s, the kind that can sand glass. He can show me the deed, he says. Katherine White, a property owner. For a second I think, ah, that’s it. He’s got the wrong person. My mother’s name wasn’t Katherine White. It was Yekaterina Simonova. Katerina Ballerina.

Richard stands in the rain without a brolly, his college scarf around his neck, his hands stuck in his trouser pockets. I step off the coach and look askance at the dark sky, starched and flat over all of Oxford. A raindrop lands on my eyelashes. I used to wonder if Mum chose England because it is so colourless. Because she never wanted it to be able to compete with her old life.

He kisses me lightly on the mouth. ‘You’re back so soon.’

‘I couldn’t stand being there a second longer,’ I say. ‘I’ll sort everything else out another time.’

‘Should we go get something to eat?’

Inside the dubious-looking eatery on the corner, I peel off my sour, wet layers and shiver. Richard lends me his scarf, which smells of him, of wood and ash and sherry.

‘How are you feeling?’ he asks, once the food comes.

‘I’m fine. Honestly.’ I stab with my fork at a mushy mountain of peas. Richard’s own mother died daintily over tea at Fortnum & Mason five years ago, the victim of a brain aneurysm. It’s almost hard not to be jealous, when Mum deteriorated over the better part of a decade.

Sometimes it felt like she was going to live for ever, that way.

‘Anything happening here?’ I ask, my mouth half full.

‘Not much. Dad rang yesterday, asked if I’m done yet,’ he says. Richard’s father seems to find it amusing, his son doing a doctorate in Classics, like Richard has to flush it out of his system before he can crack on with becoming a trader in the City, or whatever it is men in their family usually do. ‘He’s still upset that Henry and Olivia split up,’ Richard adds, referring to his older brother and his brother’s long-time, if not lifelong, girlfriend. ‘I didn’t say that Henry told me he’s planning to quit his job and travel Europe this summer.’

‘Right, about this summer.’ I swallow hard. ‘I’m thinking of applying for a short-term project in Moscow.’

His eyebrows rise. ‘I know you wanted to spend some time there, but – are you sure? Have you talked to Windle?’

‘You know how he is. I’ll make it up when I’m back. He won’t care.’

‘I wish my supervisor didn’t care.’

‘It is the best thing.’

Richard chuckles. ‘But would you be home in time for our wedding?’ he says, half joking. He doesn’t sound put off quite yet, but Richard is rarely put off. His sturdiness and his steadiness and his sameness are what endeared him to me in the first place. In Richard’s world, people die neatly of invisible brain aneurysms. They do not self-destruct. In Richard’s world, it is a shock when one’s childhood sweetheart is not, in fact, the love of one’s life.

‘Don’t be daft.’ The peas taste like bits of rubber in my mouth. Maybe I somehow knew Mum wouldn’t be attending our wedding when we first set the date. Maybe I purposely put it just out of her reach, thinking how she’d only arrive late, her face cherry red, how she’d start snoring at the ceremony, arms and legs flung over other guests’ chairs, her body draped over her own chair like a dishcloth.

How she’d still be in her nightgown.

‘I’ll need some extra time in Moscow anyway,’ I add. ‘You know. To let friends and family know about Mum?’ I can’t think what people normally do when someone dies. But people normally have other people.

I shovel in more peas.

‘Where’s the position?’ asks Richard. ‘There’s a rather famous university in Moscow, isn’t there, what’s it called—’

‘Lomonosov. It’s just an idea, really.’

Richard drops his gaze to his own platter of what might have been a shepherd’s pie in a past life. I can see him trying to work it out around the margins. He pushes around a glob of pie and clears his throat. ‘Why don’t I join you?’

‘You just started writing up.’ The peas sit like lead in my stomach. ‘You’re so busy. And maybe I … I don’t know. I need to get away for a bit.’

‘Is that all it is?’

‘That’s all it is.’ If Richard can just hold on for a few more months, then we never have to speak of Mum or Russia again. It’ll be a silent addition to my wedding vows: To have. To hold. To be Rosie and never Raisa, ever again.

‘Well, I’d miss you.’ Perhaps feeling guilty, he adds, ‘I understand. It was just you and Kate, the two of you, for so long.’

The two of us. He’s right. So why did it always feel like I lost my whole family over the course of one single night in Moscow? Like Mum’s blood was spilt there too, all over our living-room floor? Or at least her lifeblood, because she never practised ballet again after we left Soviet Russia. Defected, people would say, but we didn’t defect. We escaped. We fled.

The peal of bells from a nearby chapel tower is a ghostly sound. Bells have rung in Oxford for centuries. That is how long my nights often seem.

Next to me, Richard stirs, but I don’t move. I’ve been an insomniac for years, and often it’s the most awake I ever feel. My father would have understood. He often worked late at night, marking papers, doing exercises. Mum blamed the mathematician in him. It’s not good for numbers to run through a person’s head, she would say, because there’s no end to them.

But if it’s numbers that keep me up, they don’t go very high.

One, two.

Tonight I think about Alexey Ivanov, whom I will meet tomorrow, and how much he and I have in common. The Last Bolshevik was published in Europe in the late 1970s and promptly banned in Russia, forcing him abroad for his own safety. But so much has changed in the USSR since 1985, under Mikhail Gorbachev. The era of political repression appears to be over. Alexey’s memoir was officially published in his homeland last year. He’s being courted by the Soviet government and has even been offered citizenship again.

I could tell him, Look, see, something had to end in order for me to go back, too.

In my case, it was Mum.

Richard lifts his head from the pillow, blinking drowsily. He’s used to this, seeing me wide awake, owl-like, in the darkness. Before I can say anything, he kisses my cheek, soft as down. Richard’s touch is always gentle, always generous; You’re safe here, he’s telling me, in his way, and soon all thoughts of Mum and Russia have faded into the shadows.

Later, the bells are ringing again on the hour. I try to sleep with my face turned into the pillow. Richard won’t be there, in Moscow. Only the shadows.

Alexey’s choice of cafe is cosy and low-lit, catering mostly to university staff and students. The leisurely atmosphere fits him. He seems to do most things easily, sitting back in his chair, flicking at the label of his teabag, looking out every so often towards the glass front of the cafe. Letting the conversation stall.

The quieter and more relaxed he appears, the more harried I feel, like I want to make up for it.

‘I’d love to hear about your new project, Mr Ivanov.’ I wrap my hands around my mug. ‘I know it’s not my background, but I’m a quick learner, and I’m keen. I’ve been doing a lot of preliminary reading this past month—’

‘Why?’ he asks.

‘I’m sorry?’

‘I looked you up. You’re in the first year of your DPhil at the Mathematical Institute,’ he says. ‘In cryptography, I understand. Codebreaking. This brings to my mind Bletchley Park. Very exciting. Why are you pivoting to Russian history?’

I was going to lie outright, but I think he’d see through it. I have to hedge.

‘I was born in Moscow,’ I say. ‘My mother has just died. Honestly, it’s made me rethink a lot of things. I want to get to know my own culture and history. My heritage.’

He gives me several seconds to elaborate, and when I don’t, he simply nods. I suppose he’s been surrounded all his life by people who didn’t want to share the long history of their pasts. I almost want to ask him: What is it like not only to share the past, but to broadcast it? To take a roomful of questions on it?

‘Alright. Well, to be frank, I could use a bit of a different perspective,’ says Alexey. ‘Because the task at hand is very different from my usual work. I’m trying to find a woman I used to know. That’s it. That’s the project. We’ll just have to see if I have enough time. Not free time,’ he adds, with a self-deprecating laugh. ‘Just time.’

I look down into my tea, let the steam sting my eyelids. Mum’s just died at age fifty-three. My father died at forty-four.

Zoya died at fifteen.

Alexey takes hold of his teabag’s wilted label, lifts the bag out, then lets it slide back in.

‘She went missing years ago,’ he continues. ‘I like to think she’s ended up somewhere in the countryside. She loved the land. She used to say she could bask in it, bathe in it, drown in it …’ He sits back, as if he wants the line to reverberate. ‘But let’s talk logistics. You may not be so keen when you hear the pay, though I’m prepared to take care of the travel paperwork and housing. You won’t have to lift a finger in that regard.’

That’s what his advert alluded to, and exactly what I’ve been hoping to hear.

‘I’ll have to do a fair bit of moving around when we get there, so you’d need to be capable of working on your own. You should also continue reading as much as you can. You’ll need a …’ He gestures vaguely. ‘An underlying knowledge base. But it’s good for young people to be exposed to history. They just have to take care.’

‘Take care?’ I repeat.

His blue eyes fix on me. ‘There is no enlightenment to be found in the past. No healing. No solace. Whatever we are looking for will not be there.’

It rings out like the chapel bells, the way he says this. Whatever we are looking for will not be there.

Can a historian really believe that?

It makes me think of Zoya, of how she’ll conjure the smell of rust and cheap candles, forcing me to recall my first winter in England, in that seedy short-term apartment. To recall how Mum would stand by the window, looking through the curtains, one foot curled up like she might dance away, lit candles on every surface, like she wanted the whole place to burn down. I’d be seated at the table, working furiously, surrounded by schoolbooks, thinking, If I can just make it to the end of this problem, if I can find this one solution, everything will make sense.

But is Zoya just trying to make me remember?

Or is she sifting my old, hidden-away memories, because she’s looking for something?

‘She’s the one who was mentioned the other night,’ says Alexey, folding his arms over his tweedy jacket.

He’s talking about the woman he hopes to find. I rub at my temples. Zoya’s not here right now, and I don’t want to think too hard about her or she might show up.

‘She was called Kukolka,’ he says.

Little doll.

I take a sip of my own tea. It’s gone cold.

Kukolka. It’s an unwelcome reminder of Mum’s porcelain prisoners back in London. I’d be happy never to lay eyes on them again, but it’s not just because they’re uncanny. It’s because Mum preferred her dolls to human company. She always did. Of all the things we could have brought with us from Russia – and we weren’t able to bring very much – she chose them.

I linger in the cafe after Alexey leaves, finishing the last of my tea, watching the flow of customers. Through the glass I can see rain peppering the pavement, slowly gaining momentum, while the awning flaps in the wind, looking possessed. People burst in holding soggy newspapers, shaking themselves off like dogs.

It rains constantly in Oxford. Nothing ever seems to dry, inside or out. But it doesn’t often storm like this, enough to empty the streets. If only I’d brought along some work, or something to do—

Mum’s notebook of stories.

I ferret it out of my bag. The spine bends with close to a creak.

The more the sky darkens outside, the brighter it feels in here. But that doesn’t make the coil of cursive any less excruciating to read. It doesn’t make anything clear.

A Note for the Reader …

A Noteforthe Reader

These stories should not be read in order.

After you have read all the others, in whatever order you like, you may return to the first one. This is, after all, a book of stories for those who know that the beginning can only be understood at the very end.

You must now close your eyes to see what I am about to show you.

If you think your eyes are closed hard enough, then let us begin: In a faraway kingdom, in a long-ago land …

CHAPTER TWO

Antonina

Petrograd (St Petersburg), autumn 1915

Tea is served in the Blue Salon at four in the afternoon, every day. Most days there are also cream cakes, custard cakes, and puff pastries, laid out on platters, or buttered bread, freshly sliced, still steaming. Yet Tonya never feels hungry. She tells herself it’s because lunch was too recent, too rich. Or because of the hideous silver-blue wallpaper of this room, for which it was given its name, which makes everything within look sickly. Or because Dmitry hardly ever touches the tea service or the display of goodies himself. Today he is counting banknotes at the escritoire beneath his breath: Twenty, forty, sixty.One. Two. Three. Everything in this house has a number.

Everything has a price.

The caravan tea is black and smoky. Tonya drinks as silently as she can.

Dmitry puts aside his wallet. He turns to fish a cigar from the sweet-smelling cedar box he stores them in. It’s easy to wonder why they bother with teatime at all, except that they might not see one another all day without it.

‘Your nightmares are getting worse,’ he says.

Her tongue feels thick, twisted against her teeth. ‘No worse than normal.’

Dmitry takes a long puff. ‘I could hear you thrashing around yesterday, even from my quarters.’

‘I dream of home,’ she says tightly. ‘Of Otrada. Perhaps it’s a sign I ought to visit.’

‘It’s out of the question for you to travel alone.’

‘But I could accompany you, next time you go south—’

‘I have no such plans for the foreseeable future. There’s a situation here with the union.’ A sigh, softened by another puff. ‘I have several rabble-rousers in my employ.’

Tonya chokes back a reply. Dmitry makes frequent trips out of town, scouring this country in search of pieces to add to his beloved collection of rarities, oddities and other treasures. He sometimes leaves for weeks on end.

She has to be home by teatime.

‘Are you bored, Tonya?’ he asks. ‘Is that the problem?’

‘I—I occupy myself,’ she falters.

‘Perhaps if you cultivated an interest in philanthropy,’ he says. ‘I was thinking the other day that a tour of the factory, even the barracks, is long overdue. And it should be to my benefit for them to see that I am a married man.’ Dmitry works away at the cigar, appearing pleased by the thought. Against the watery hues of the wallpaper, his profile looks sharp, princely. Dashing, perhaps. Tonya has lived in this house long enough to overhear the giggles of the young housemaids, their swoons: how different their master is from the others of his station! He treats his inferiors with such respect, such benevolence! He is no hard-hearted despot, no devious tyrant, no cruel handler! They are right. He is none of those things.

Downstairs, at least.

Tonya is in the middle of reading Alexander Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin when Dmitry announces that it is time to take a drive. Did she accidentally feign interest yesterday in the idea of a factory tour? She isn’t even sure what his factory makes. Magnetos, she has heard people say in passing. Things to do with the ongoing war against Imperial Germany. In the motorcar Tonya closes her eyes and tries to recreate the stunning, romantic world of Pushkin,but her husband’s voice cuts through it.

‘You’ve let your hair down,’ he notes, as if he never instructed Olenka to keep it so. ‘I abhor those matronly updos. You might soon be seventeen, but you’re only a girl.’ Dmitry leans over and touches her ear, pulls on one pearl-drop earring. ‘I like you like this. The way you looked the day we met.’

‘Should married women look as I do?’ she says, trying not to sound morose.

‘Nobody looks as you do,’ he says.

His tone suggests that he will visit her bed tonight. It would be the first time since his return from his most recent trip. She knows from the chauffeur’s whispers to Cook that Dmitry pays regular visits to the docks, when he is here in the capital. That he likes the girls well-broke, like a horse.

Not all the staff are as blinkered as the housemaids.

Tonya turns to the window. The factory is on the Vyborg side, across the Neva, but the driver seems to be taking a long way around. She blinks, refuses to admire the cityscape. It has been nearly a year and a half since she married Dmitry, over a year since he brought her to Petrograd. Still the only thing she likes about the capital is the single aloof spire of the Admiralty, the way it catches the sunlight. The Neva is not terrible, either, though it stinks of cod and seagull. And sometimes she enjoys seeing the laundry hung on lines in the yellow courtyards, hearing it flap in the wind, flap-flap-flap. She wants it to blow away. She wants all of it to blow away.

Eugene Onegin, she tells herself. Think of Eugene Onegin.

The tour is deadly dull, led by the foreman, a stubbly man called Gochkin. Tonya runs her hand over the tables, tools, machinery for which she has no name. The workers give her hard stares, but then so do Dmitry’s society friends. Tonya might come from provincial gentry, her father might be a prince, but to the old St Petersburg elite, she is lowly country stock. Her home village is so deep in the country that it is hardly considered the same country.

Young and old, the faces of the workers are slick with grime, and unsmiling. Dmitry seems not to notice. He is friendly with everyone, shaking hands, slapping shoulders. Asking after babies. Tonya knows her husband fancies himself a liberal. He feels bad that his forefathers ever owned serfs.

He does not, however, feel bad for owning her.

After the tour Tonya joins Dmitry and Gochkin on the high platform that overlooks the factory floor. The men retreat to the office of the latter and Tonya strays to the railing. She plays with the ends of her hair, picks over her sleeve for the smallest threads. This stiff-necked dress is horribly stifling. Her jewellery feels weighty. Uncomfortable and restless, she shifts her attention to a group of workers who have gathered below. Young men, laughing, talking amongst themselves.

The rail is suddenly the only thing that keeps her standing.

Tonya doesn’t know who he is. He was not present during the tour. She would have remembered if he were. He is dark-haired, lean, but they all are, no doubt subsisting on cabbage soup and kasha. And he is handsome. So handsome that she feels itchy, like lice might have burrowed into her stockings.

‘You have an audience, Andreyev,’ someone says.

‘He always has,’ remarks another.

He is the one they are calling Andreyev. He looks up, barely, and meets her gaze. His smile is knowing – no, mocking – and her heart races. Perhaps some wealthy do-gooders have barged in here recently, hoping to elevate the sorry lives of the working classes, looking for a purpose for their pampered lives, and he is mistaking her for one of them. One such couple came to call at the house, just the other day. They were horrified at what they’d witnessed in a workers’ barracks, nearly foaming at the mouth as they described cockroaches clinging to plank beds, whole families jammed into spaces unfit for livestock, and the smell, oh, the smell!

Tonya can only imagine the smell of someone like him. Of the revolting hand-rolled cigarettes that the natives of Petrograd love to smoke. Of the smog and soot of the factory pillars. Of the city streets. Of sweat.

They have looked too long at one another. She flushes. He wipes something from his eye, dirt, or just the sight of her, and turns away.

Since the start of summer Tonya has taken early, winding walks, all the way from the house on the Fontanka up to the Neva, one river to another. Dmitry usually sleeps late, and it’s a chance to be alone, unguarded, uninhibited, for no one else is about between five and six in the morning, except droshky drivers and soldiers. And a few troublemakers.

People like – him.

She is just passing the newspaper offices on Nevsky Prospekt when she sees him. Just by chance, for a remarkably sizeable crowd has formed around Andreyev: a clutch of students, in blue caps; workers with their tarred hats and unwashed heads; drivers in their signature mink stoles. Tonya is able to join the crowd at the fringes. He is the only one speaking: The old Russia shall make way for the new! And in this new world, all will participate, all will partake, even you lads, even you ladies, even you, comrade, even—

You.

He sees her now. Smiles, as yesterday, at the factory. She feels shaky, shivery. As if he is nearer than he actually is, near enough for his hands, his mouth, his body, to be all over hers.

Mama once warned her of feeling this way. Of inexplicably wanting something, someone, enough that your blood runs hot, until it bubbles. Everyone feels this when they’re young, said Mama, but it passes as quick as it comes,and Tonya only giggled, because it was unthinkable, both the bubbling of blood and such a feeling of wanting.

He is still orating to the crowd: Can you see the future that lies before you? Will you reach for it? Will you take it for yourselves?

But he is watching her still.

You will all of you live two lives, comrades! One is finished, and the other is now!

Tonya tells herself that it is easy to adore a performer, and to forget that they perform for everyone. She feels her own lips moving, saying this. But the voice she hears is his.

As the autumn cedes to winter, Anastasia Sergeyevna, Dmitry’s widowed mother, grows too weak to continue living in her dacha by Lake Ladoga. She is moved into their house on the Fontanka and decides to occupy the spare study on the ground floor, a wood-panelled, little-used space that stinks of death even with her in it. In her youth Anastasia was a popular hostess, a beloved wife, a saintly woman. At least that is what people say, the few friends who drop by, who depart with their faces drooping, like the branches on the maple trees outside.

Now she lies as still as the heavy, dark furniture of the room she has chosen for herself.

At Dmitry’s request, Tonya sits by her mother-in-law’s side for an hour every day. After the first few woefully awkward visits, she brings along Eugene Onegin, and reads aloud until the woman falls asleep. It is easy enough to do, in here. Anastasia suffers headaches behind her bad eye, and so the curtains are never drawn. The only light in the room, the only life, comes from the fireplace.

Today Tonya begins: ‘My whole life has been a pledge to this meeting with you—’

‘Have you read Pushkin before?’ interrupts Anastasia.

‘I enjoy his poetry,’ says Tonya, nervously. ‘I am particularly fond of—’

‘Olenka tells me you spend hours every day in the library. Have you always read so much?’

‘There weren’t many books in my parents’ home.’ Tonya tries to avoid looking in Anastasia’s bad eye. ‘Nothing like—’

‘Do you miss home?’

‘At times,’ says Tonya, trying not to think of Otrada; of the nearby village of Popovka; of the creek gleaming silver, the moon tossed over the trees. Of running barefoot; of breathing deep. ‘But I am happy here,’ she adds. She tucks in her skirts, turns the page, knows she’s giving away her lie with these small movements. Her mother-in-law has fallen silent again. Tonya blunders on, reading until she sees that Anastasia’s good eye has closed. The bad eye does not appear able to close, not like that. The lid has petrified in place.

Tonya puts the book aside and stands from her chair with a yawn of her own.

She has been waking up every day at five, to see him speak.

She has her hand on the door handle when she hears the rustling of blankets behind her. She dares to take another look at the divan, at the heaping of pillows and deerskins, the withered figure of Anastasia lost amongst them. The flames in the background, flickering low.

‘I mean to ask you, child. I know about your displeasing dreams. Your disturbed sleep.’ Anastasia’s voice is not unkind. ‘Is something troubling you?’

‘My dreams began in childhood.’ Here, at least, there is no need to lie. ‘I have suffered them as long as I can remember.’

‘Very well.’ The good eye is open again, pale, penetrating. ‘But if I can help, just tell me how.’

The good weather ends early here. A winter chill slinks through Petrograd like a serpent, without any warning. Tonya awakens one morning blue-lipped and hardly breathing. Unable to fall back asleep, she climbs out of bed. She draws the velvet-tasselled curtains, opens the doors to the balcony. Her bedroom overlooks the Fontanka, and the river is as lifeless as she feels. She inhales. The air bristles in her lungs.

She could ring for her breakfast and take it in bed. Olenka would tend a flawless fire. There is nowhere to go, nowhere she has to be.

Is this freedom? Or a spacious cage?

For a moment, she hesitates, but only a moment. She has become practised at this routine: dressing on her own, not bothering with her hair; tiptoeing out her own boudoir and past Dmitry’s rooms and down the central stairs; ignoring the noise of the servants, dim and chattery and echoed in the walls, like mice. All the way through, along every corridor, Tonya keeps her shawled head bent. She goes out the grand foyer, shutting the bronzed doors gently behind her.

Outside, a hostile wind blows, bites at her face. Snow blankets the parquet along Nevsky, and is still falling, soft and sugary. Although the streets are mostly empty, Tonya can hear the quivery jingle of sleigh bells, the whinny of horses. Petrograd is waking up. Her hands buried in her sable, she hurries now to cross Nevsky at the Anichkov Bridge and continue up Liteyny. It is close to a forty-minute walk to the Neva, but by the time she reaches it, she has warmed.

There is an overturned sleigh dug into the muddy slush of the embankment, surrounded by people. He stands somehow balanced upon it, on the runners. He gestures to the bridge, to the river, as if he can see across that growing expanse of ice the very future he is taking pains to describe.

She will be no more, this frail Russia! She will be born anew!

He is a Bolshevik.

Tonya has stood in enough of his crowds by now to know that his name is Valentin Mikhailovich Andreyev. That he is twenty years old, a disciple of Vladimir Lenin, a revolutionary. She has learnt far more about their small but vociferous political party than she probably should; only yesterday she found a published pamphlet by Lenin, What Is to Be Done?, in one of Dmitry’s libraries, and read it aloud to Anastasia, hoping Dmitry’s mother might understand everything Tonya could not. Revolutionary theory. Class consciousness. Social democracy. A world of strange, new, meaningless words.

She prefers the ones that Valentin Andreyev uses in his speeches.

Tonya wanders now to the rail of the bridge. She will remain until Andreyev has finished. They will exchange a wordless glance. He will smile as he does, and then she’ll walk on, and it will all happen again tomorrow and the next day. He is only a silent, secret fantasy, one that she guards. She has nothing of her own in Petrograd. Not her furs, her lace. Not her hair, her skin, her breath. Nothing except this.

She has started to recognise his closing lines, the things he wants people to remember. She removes her muff and wipes a layer of snowflakes off her shawl. The cold seeps into her gloves. Bells begin to ring in the distance, high and haughty, while the wind swoops by, even higher. She leans against the cast-iron cladding of the rail, glancing in the direction of the Kresty Prison, on the opposite bank of the Neva. Infamous home of the Tsar’s political prisoners, it is made of faded red brick. Yet today it looks shiny, scratchy-white, like a Christmas ornament.

That is where people like Valentin Andreyev end up.

‘You are devoted to the cause, comrade,’ says a voice from behind her.

Tonya turns, but fails to reply. There’s a slight rush in her ears. He is standing there. The other onlookers have dispersed, and the crowd has scattered. She observes him mutely, almost at a gape. His wool jacket is strewn with holes, and the wind from the river must sail right through. The flurries dust his dark hair, his shoulders, even his smile. Yet she is the one trembling.

‘I was certain you’d stop coming, now the weather’s turned,’ he says.

He must know she is Dmitry’s wife. He’s being disingenuous, but then she has been, too, acting like she is free to be here, standing with him, staring at him.

‘What’s your name?’ he asks.

‘Antonina Nikolayevna,’ she says without thinking. It’s too many syllables. Too formal. He is already too close for that.

‘I’ll be on the other side of the bridge on Saturday,’ he says. ‘Will you come?’

‘I don’t—I don’t know.’

‘We’ll see, then. Antonina.’

He says it like a challenge, like he doesn’t expect to see her again, now that they have spoken. Now that he has come down to her level. She doesn’t know whether she wants to prove him wrong or not. She watches as he saunters off, hands in his pockets. Modestly, like he was never atop that sleigh, never addressing the people, never promising a thing. Quietly, like maybe there is more to him than that: Valentin Andreyev, the Bolshevik.

At teatime there is a caller: the Countess Natalya Fyodorovna Burzinova, heiress and socialite, mother and widow, friend and foe. Dmitry and Natalya met as children, and the intimacy between them is old and obvious. He calls her Natasha, a familiar name; Tonya doesn’t dare. She used to imagine that the Countess would be something of a mentor, an older sister, a replacement for Nelly and Kirill, her dearest friends back home.

By now she knows better.

Dmitry isn’t home for tea, which has often been the case of late. More trouble at the factory, if the servants are to be believed. Once the Countess has swept herself into the Blue Salon, Tonya rings for a tray. The two women regard one another until Tonya backs down, looks instead at the wallpaper, at the places where it curls, where the ends do not quite meet.

The Countess is a regular visitor, yet somehow she always catches Tonya by surprise.

Natalya is older, self-assured, sly. She has the habit of rubbing the silver Orthodox cross that hangs around her neck. Rub, rub, rub. Today it matches her snake-like silver earrings. Natalya often accessorises with silver, perhaps to offset – or to accentuate – the flaming redness of her hair. People say that the Countess must paint her hair, for everything else about the woman appears deliberate, even the contours of her face. But anyone acquainted with Natalya’s two children would know the beetroot colour is indeed a family trait.

Rub, rub, rub.

‘I was hoping to speak to you alone,’ says the Countess. ‘Is it true that you set off every morning and walk the city?’

‘I enjoy the quiet.’

‘It’s not quiet any more.’ Natalya taps her falcon-claw fingernails on the arm of her chair. ‘It’s anarchy. And perhaps you’re unaware, being a country mouse, but when a young woman regularly ventures out on her own at odd hours, rumours tend to follow.’

Tonya has heard her own share of rumours by now. She’s heard, for example, that the young Natalya was desperately in love with Dmitry; that Natalya’s scheming, social-climbing parents intervened, marrying their daughter off to the decrepit Count Burzinov. Oh, if only the Count had died earlier than he did! For by that time Dmitry had already departed on a fateful sojourn to the lower provinces, and was soon to return with, amongst other trinkets, his new bride.

Gossip abounded about that too, of course; about Tonya. The only child of a notoriously reclusive family, not seen in the Imperial Court for decades—

There are rumours enough to float a barge, in this city.

‘Dmitry knows about my walks,’ says Tonya. ‘He doesn’t mind.’

‘He forgets that a wife is different than a pet, a servant or an employee.’ Rub, rub, rub. ‘He’s had too many of all those. Anyway, I’ve come to say that you’d do better to stay home, darling, what with the demagogues, the radicals, the demonstrators on the streets. And you yourself so inexperienced, so young, so provincial …’

The Countess is still speaking – Tonya? Tonya? – but Tonya is no longer listening. The demagogues, the radicals. There he is, every morning, standing up there, speaking of freedom. Looking like freedom. She thinks of the way he said her name, Antonina, the way it came off his tongue, his way.

Anastasia remarks that Tonya looks different lately. Maybe it’s the good eye going bad too, seeing things, but Tonya doesn’t say so. Your face is so bright, child, Anastasia says, like you don’t view me as a chore any more