8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: adlima GmbH

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

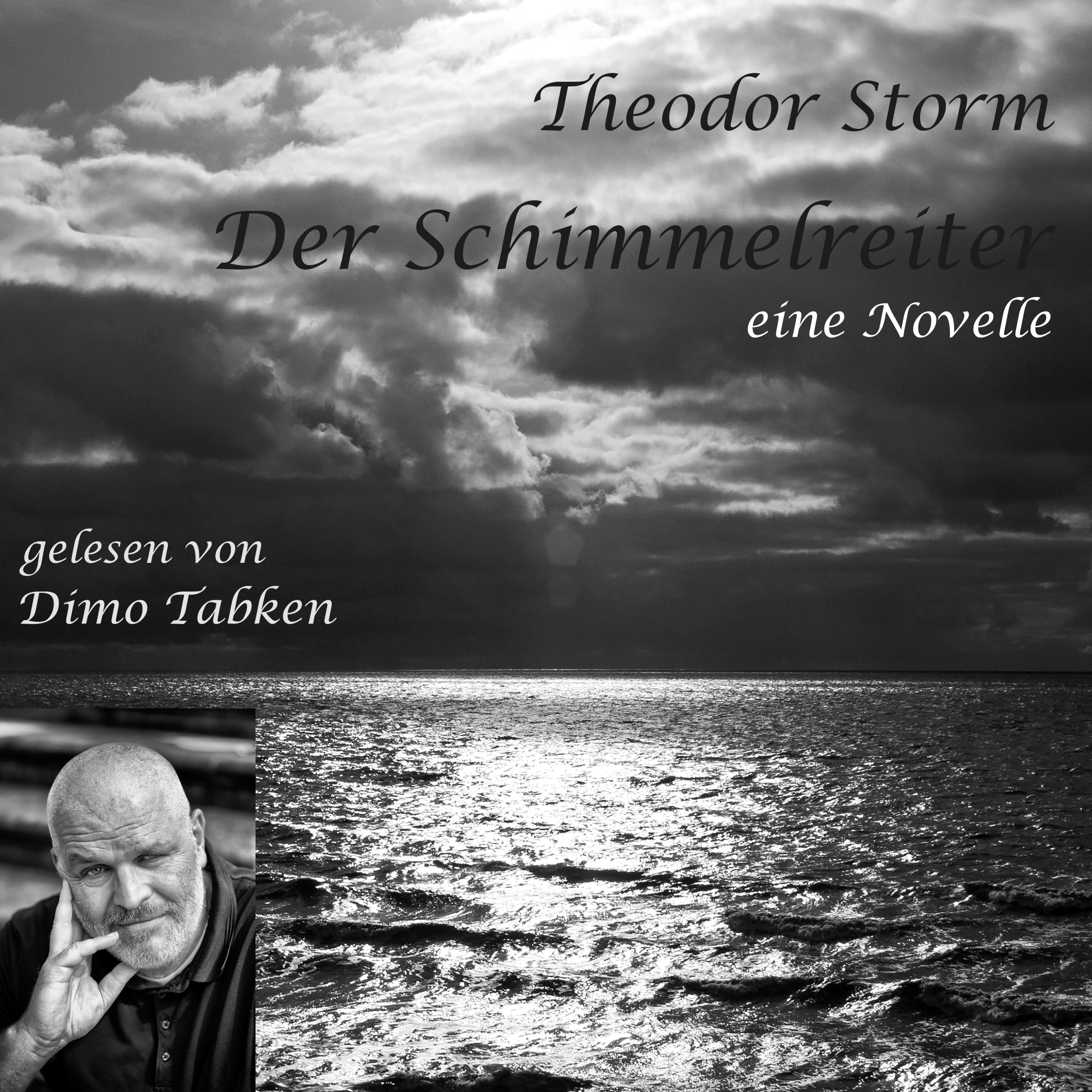

Klassiker in Englisch Niveau A1. Die Bücher dieser Reihe eignen sich für Jugendliche und Erwachsene, die mit klassischen Werken ihre Lesefähigkeit verbessern wollen. Englisch Niveau A1, durchgehend in englischer Sprache. "Der Schimmelreiter" ist eine der bekanntesten Novellen von Theodor Storm. Die Geschichte, angesiedelt in einem norddeutschen Küstendorf, thematisiert den Kampf des Menschen gegen die Naturgewalten und den Aberglauben der Dorfgemeinschaft. Die Geschichte dreht sich um Hauke Haien, einen ambitionierten und intelligenten jungen Mann, der innovative Ideen zur Verbesserung der Deiche hat. Hauke steigt durch seinen Fleiß und seine Intelligenz auf und heiratet Elke, die Tochter seines Vorgängers, was ihm den Weg ebnet, selbst Deichgraf zu werden. Nachdem er Deichgraf geworden ist, setzt Hauke seine fortschrittlichen Pläne um, einen neuen, besseren Deich zu bauen. Trotz seiner fachlichen Fähigkeiten stößt er jedoch auf Misstrauen und Widerstand in der von Aberglauben durchdrungenen Dorfgemeinschaft. Sein Kampf wird zusätzlich erschwert durch mysteriöse Vorfälle und das Misstrauen, das sein unheimlicher Schimmel bei den Dorfbewohnern weckt. "Der Schimmelreiter" ist eine tiefgründige Erzählung über Menschlichkeit, Isolation und den unerbittlichen Kampf gegen unaufhaltsame Kräfte. Storm verwebt in seiner Novelle Realismus mit Elementen der norddeutschen Sagenwelt und schafft so ein packendes, atmosphärisch dichtes Meisterwerk der deutschen Literatur.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Theodor Storm

The Rider on the White Horse

Englisch Lektüre A1

Chapter 1

I am riding across a dam in a heavy storm. To my left, I see empty land. To my right is the sea. All I can see are gray waves crashing against the dam. The water splashes me and my horse. The sky and the earth look the same. The moon is mostly hidden behind clouds.

It is very cold. My hands are cold, too. I can hardly hold the reins. It is getting dark. I can hardly see my horse's hooves. I don't see a single person.

The weather has been bad for three days now. I have been staying with a relative. Today I want to ride in to town. The town is a few hours away.

I set off in the afternoon.

My cousin called after me, “Wait until you get to the sea. Then turn back. Your room will be kept free for you!”

The wind is almost blowing me off the embankment.

I think briefly, “Should I turn back?”

But the way back is longer than the way to the city. I ride on. Now I see a dark figure on the dam. It's a rider on a white horse. The rider is wearing a fluttering, dark cloak. I see his face. It is pale. His eyes are shining. They're looking at me. I don't hear any hoofbeats. I don't hear the horse breathing, but the rider rides right past me.

I'm still thinking about the figure when suddenly it flies past me again. The cloak almost brushes my arm, then it disappears silently into the darkness.

I ride slowly after it. Down in the marshland, I see water glistening. The water is moving rapidly. I can't see the rider anymore. But I see something else. I see many lights. Close in front of me, I see a large house. It is halfway up the dike. Lights are burning in the house.

I can see people inside. I can hear their voices. Glasses clink. My horse walks down the path to the house of its own accord. It stops in front of the door. The house is an inn. A servant comes to meet me. I hand him the reins.

I ask, “Is there a meeting here?”

The servant replies, “The dike reeve is here with a few other men. They are discussing the flood.”

I enter.

About 12 men are sitting at a table. On the table is a large bowl of punch. A particularly stately man is speaking. I greet all the men.

I ask, “May I sit with you?”

They nod.

I say, “Are you keeping watch? The weather is terrible outside.”

One man says, “Yes. We are safe on the east side, but it is dangerous on the other side. The dams there are old. Our main dam was reinforced in the last century. We have to hold out for a few more hours. There are people outside. They will warn us.” Someone pushes a glass toward me. It is steaming.

I thank them.

The man next to me is the dike master. We strike up a conversation. I tell him about my encounter with the rider on the dike.

Suddenly, all conversation stops.

The dike master listens attentively.

A man shouts, “The rider on the white horse!”

Everyone looks frightened. The dike master stands up.

He says, “You don't need to be afraid.”

I get goose bumps.

I ask, “What about the rider on the white horse?”

Behind the stove sits a small, thin man. He is wearing a black shirt. He hasn't said anything yet, but his eyes are alert. He is not asleep.

The dike master points to him.

He says, “That's our schoolmaster. He can tell the story best, but not as well as my old housekeeper Antje Vollmers.”

The schoolmaster replies, “You are joking, dike master. Don't compare me to your stupid dragon!” The dike master laughs, “Yes, yes, schoolmaster, but stories like that belong to dragons!”

The schoolmaster smiles smugly.

He says, “We have different opinions on that.”

The dike master whispers in my ear, “He's a little proud. He studied theology, but his engagement fell through. Now he's a schoolmaster here.”

The schoolmaster comes out of his corner. He sits down next to me at the table.

Some young men shout, “Tell us! Tell us, schoolmaster!”

The schoolmaster says to me, “All right. I'll gladly tell the story, but there's a lot of superstition in it.”

I say, “Please don't leave out the superstition. I can tell the difference between truth and superstition.”

Chapter 2

The old man smiles at me kindly. He says, “All right! I'll tell you now.”

This is his story:

Many years ago, a dike master lived in this area. He knew a lot about dams and locks, but he hardly ever read books. He taught himself everything. Perhaps you have heard of Hans Mommsen. He was a farmer, but he built compasses, clocks, telescopes, and organs.

The dike master's father is similar. He has a few fields and a cow. In autumn and spring, he measures the land. In winter, he sits in his living room and draws.

The boy often sits with him. He watches his father.

One evening, the boy asks his father, “Why do you write everything down so precisely? Why can't it be any other way?”

His father says, “I don't know. That's just how it is. Do you want to know more? Then look for a book on the floor tomorrow. It is called ‘Euclid.’ The book will explain everything to you.”

The next day, the boy goes to the floor. He quickly finds the book. The boy puts the book on the table.

His father laughs. It is a Dutch Euclid. Neither of them understands Dutch. The father says, “Yes, yes. That book belonged to my father. He understood it.”

The boy looks at his father. He asks, “Can I keep the book?”

The father nods.

Then the boy shows him a second book.

He asks, “This one, too?”

The father says, “Take both. They probably won't help you much.”

But the second book is a Dutch grammar book. The winter is still long. By spring, the boy has almost completely understood Euclid.

The schoolmaster says, “That's what they say about Hans Mommsen, but in our story it's about Hauke Haien. That's the boy's name.”

Then the schoolmaster continues.

The father notices that Hauke is not interested in cows and sheep. So his father sends him to the dam. Hauke is supposed to shovel earth with other workers.

His father thinks, “The hard work will distract him from thinking.”

The boy shovels earth, but he always has Euclid in his pocket. The workers take a break, but Hauke sits on his wheelbarrow with the book.

In autumn, the work stops. Hauke stays at the dam anyway. He stares at the water for a long time. He sits there for hours. He sees the murky water. It keeps hitting the same spot. The water digs into the dam. Sometimes the water reaches his feet, then Hauke moves up a little. He sits there again. He doesn't hear the water. He doesn't hear the seagulls either. He only sees the edge of the water.

Sometimes he nods. Sometimes he draws a line in the air with his hand. He wants to give the dam a gentle slope. It gets dark. He can't see anything anymore. Only then does Hauke go home. His clothes are wet.

One evening, Hauke enters the living room. His father is sitting at his measuring instruments. His father is startled.

He says, “What were you doing outside? The water is dangerous today.”

Hauke says, “Yes, but I didn't drown.”

After a pause, his father says, “Not this time.”

Hauke says, “Our dams are bad.”

His father asks, “What do you mean?” Hauke says, “The dams! They're no good.”

His father laughs.

He says, “What do you mean, boy? You must be a child prodigy.”

Hauke doesn't let himself be distracted.

He says, “The water side is too steep. We could drown behind the dam.”

His father takes some chewing tobacco. He asks, “How many carts did you push today?”

He is annoyed.

He realizes that the hard work has not stopped Hauke from thinking.

Hauke says, “I don't know. As many as the others. Maybe more. But the dams have to be different!”

His father laughs and says, “Maybe you'll become a dike master one day, then you can change everything!”

Hauke says, “Yes, Father.”

Even after work in October, Hauke continues to go to the dam. He waits for the storm in November. He waits for it like a child waits for Christmas. During a spring tide, he lies alone on the dam. Wind and rain whip him. The seagulls cry. The waves tear grass from the dam. Hauke laughs angrily.

He shouts, “You can't do anything. People can't do anything either!”

Sometimes he brings soil home with him. He sits down with his father. He kneads small dams out of soil, then places them in a shallow basin filled with water. He watches the water and soil, or he draws on his slate. He draws a dam.

Hauke doesn't talk to the other children. They don't want anything to do with him either. In winter, he goes out onto the dam despite the frost. In front of him lies a sheet of ice.