3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: BookRix

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

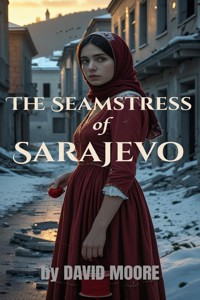

The Seamstress of Sarajevo is a haunting and tender historical novel set during the brutal Siege of Sarajevo (1992–1996). Aida Selimović, a young Muslim woman with a gift for sewing, risks her life to smuggle messages and supplies hidden in the seams of garments. As the city crumbles around her, she falls in love with Luka, a Serbian soldier whose allegiance may cost them everything.

Torn between survival and betrayal, Aida must navigate love across enemy lines, protect her family, and reclaim her future one stitch at a time. This is a story of war, identity, resilience—and the healing power of thread.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Chapter 1 – Needle & Thread

The sound of thread snapping was louder than the first distant thump of artillery. Aida Selimović, crouched on the wooden floor of her family’s small tailor shop near Baščaršija, let out a soft curse in Bosnian under her breath. Her fingers, calloused and deft from years behind a needle, paused over the torn lace of a wedding gown.

The needle had caught again. She tugged gently, trying not to damage the antique silk, but the thread had split right along the hem. Outside, the streets of Sarajevo pulsed with unease, like a lung holding its breath. The morning had brought rumors of troops surrounding the hills again, Serb soldiers with heavy boots and heavier weapons. But inside the shop, Aida worked as if normalcy could still be pieced together—stitch by careful stitch.

Her mother, Sabina, appeared in the doorway behind her, wiping her hands on her apron. “Still working on that dress?” she asked, her voice brittle from worry and cigarettes. Her eyes darted to the window, to the sky beyond.

Aida nodded. “She’s supposed to get married next week. I told her I’d have it ready.”

Sabina shook her head. “There won’t be any weddings, Aida. Not while the city waits like this.”

Another rumble sounded—closer this time. Aida looked up. The lights in the shop flickered as if the city itself shuddered.

She placed the needle down carefully. “If we stop sewing,” she said quietly, “we stop believing.”

Her mother didn’t reply. She simply turned and walked into the back room, where the radio played low and constant—updates no one trusted, voices no one believed. Aida sat in silence a moment longer, then lifted the dress again, its white fabric looking ghostly in the half-light.

Her fingers moved with instinct, rhythm. In and out, thread looped and tied. She had learned to sew at her grandmother’s knee, stitching buttons onto her father’s shirts before she was tall enough to see over the counter. Sewing was tradition. It was survival. It was faith in small things.

Suddenly, a scream shattered the morning calm.

Aida dropped the gown and ran outside. Down the narrow street, a plume of smoke rose where a mortar had struck. Neighbors were gathering, shouting. A boy—no older than seven—lay crumpled in the road, blood blooming from his chest like a crimson flower.

Someone yelled for a doctor. Another ran toward the boy. Aida stood frozen, heart pounding, nausea rising.

Her world tilted. The war wasn’t on the edge of the city anymore. It was here.

Back in the shop, her hands trembled as she folded the wedding gown and placed it in its box. Not to be delivered. Not now.

She walked to the window, drawing the curtain shut. Her mother lit a cigarette in the back, her face pale.

“They’ve started,” Sabina said softly.

Aida nodded. “Yes.”

Outside, Sarajevo was unraveling. But inside the shop, beneath the smell of ash and silk and fear, Aida reached again for her needle and thread.

If she was going to survive this war, it would be one stitch at a time.

Chapter 2 – City Under Fire

The next morning brought no peace—only smoke. Aida awoke to the sharp clap of mortar fire echoing across Sarajevo like the sky cracking open. Her mother had pushed a dresser against their front door during the night. It leaned at an angle now, books and pans piled on top like a fortress built by desperation.

Aida sat up on the mattress laid out in the living room. Her little brother Emir, only ten, slept curled beside her, his face pressed into a pillow. Their father had vanished two weeks before the siege began. One morning he had left for the bakery, and he never came home. No body. No answer. Just silence.

Now, there was only the three of them—Aida, Emir, and their mother—trapped in a city being strangled by snipers and shellfire.

She walked to the small kitchen, stepping over a box of canned beans and powdered milk. Outside, the once-bustling street was deserted. A corpse lay near the curb. A man. His jacket flapped in the wind like a flag. No one moved him. That was the rule now—don’t risk it. Not unless it was family.

Sabina sat at the table, counting batteries and matches with the precision of a surgeon.

“Go to the shop today,” she said without looking up.

“What for?” Aida asked, her voice thick with disbelief. “No one’s coming in for dresses.”

Sabina raised her eyes. “The neighbors still need clothes mended. Blankets, too. And I heard Fatima’s son needs a coat repaired. You still have your sewing kit there.”

Aida hesitated. Going out meant crossing sniper alleys. A wrong turn could kill you. Still, Sabina was right. The work, however small, kept people alive. And kept her sane.

She dressed quickly—layers of sweaters under a heavy coat, a scarf wrapped tight around her head. In her coat pocket, she placed scissors, needles, a half-spool of thread. The cold air outside bit into her skin, but the silence was worse. Sarajevo had once been a city of laughter and traffic, of students, musicians, poets. Now it was a hushed tomb.

Aida moved swiftly, keeping to the shadows. She passed the empty cafe where she and her father once sat for strong Bosnian coffee, the window now shattered. A painted mural of a dove was pockmarked with bullet holes.

She reached the tailor shop in ten minutes, heart pounding with every step. The building was intact—miraculously. Dust coated everything inside. She latched the door behind her and let out a slow breath.

The sewing machine was still on the table. Aida ran her fingers over it, then reached for the wooden box of supplies tucked beneath the counter. Everything was there: extra needles, old thread, scraps of fabric folded neatly in a plastic bag.

She sat and began to sew a tear in a child’s winter coat that had been left weeks ago. Her hands knew the pattern before her mind caught up. Stitch. Pull. Knot. Repeat.

An hour passed. Then a knock at the door startled her so badly she nearly stabbed herself with the needle.

She peeked through the cracked glass. It was Mrs. Avdić, an elderly widow from the next building. She clutched a wool blanket with a long gash through it.

“I didn’t know you were open,” the woman said with a bitter laugh as Aida let her in. “I figured the bombs got you.”

“Not yet,” Aida replied. She motioned to the table. “Let me see.”

As Aida sewed, Mrs. Avdić spoke in hushed tones about food lines, sniper attacks, and how she’d buried her dog to keep from starving. “I couldn’t do it,” she whispered. “I buried him instead.”

When the tear was repaired, the old woman touched Aida’s hand.

“Thank you, my dear. We may not have power or water, but stitches? Stitches are still sacred.”

Aida smiled faintly.

After she left, Aida stood in the doorway of the shop. Across the street, smoke curled from a shattered rooftop. Somewhere beyond that, gunfire cracked again.

She didn’t cry. Not yet.

Instead, she turned back inside, picked up her thread, and began to sew.

Chapter 3 – The Empty Streets

Aida had never known silence like this.

Not the soft hush of snowfall or the reverent stillness of mosques before prayer—but the silence of a city waiting to die. Sarajevo’s streets, once filled with merchants’ voices, students laughing, music drifting from cafes, now held nothing but wind and the distant thud of mortars.

She moved through the early morning chill like a shadow, her sewing kit wrapped in a faded scarf and tucked into a cloth satchel. She wore her father’s old coat, two sizes too big, and boots so worn her socks peeked through. In one pocket, she carried a small loaf of stale bread, bartered the day before for patching a wool shawl.

Each block she passed was a risk. Sniper Alley, they called it—Zmaja od Bosne Street. The name sounded like a storybook, but the danger was very real. Serbian snipers watched from the hills, picking off anyone who dared to move. Aida had memorized the safest paths: alleyways, broken fences, holes in concrete walls.

Today, she had two deliveries: a patched baby blanket for a neighbor named Jasmina, and a winter coat hemmed to fit the frail shoulders of her elderly husband. Both had offered sugar cubes in return—luxuries rarer than gold.

She reached the first stop and tapped lightly on the door. Jasmina opened it just enough for a whisper to escape. Her eyes were red and tired.

“Thank you,” she said, taking the blanket. “It’s for Faris. He cries less when he’s warm.”

Aida nodded. “Sugar, like you promised?”

Jasmina reached behind the door and produced three tiny cubes, wrapped in a strip of newspaper. “I saved them from Eid. I wanted them for tea, but Faris—he needs this more.”

As Aida turned to leave, Jasmina grabbed her arm. “Be careful near the square,” she said. “There was shelling this morning. They’re aiming lower now. Not just the hills—windows too.”

Aida thanked her and moved on, keeping low and quick. Snow began to fall lightly, dusting the rooftops in a deceptive layer of beauty. Sarajevo still had its charm, she thought. Even in ruins.

At the next stop, the old man took the coat with trembling hands. His fingers were blue at the tips.

“You’re the girl with the needles,” he said, voice wheezing. “You’ve got magic in those fingers.”

She offered a smile, but it faded when he reached into a worn satchel and handed her a folded envelope.

“Deliver this for me,” he whispered. “To the other side.”

Aida froze.

The “other side” meant across the front line. Serbian-held territory. The envelope was sealed, but the paper was thin, nearly see-through. She could make out a name written in trembling Cyrillic.

“I can’t,” she said, shaking her head.

“You can,” he insisted, eyes shining with unshed tears. “You go through the checkpoints. You’re just a girl. They won’t suspect you.”

She opened her mouth to protest, but the old man pressed the letter into her hand.

“She’s my daughter,” he said. “Married a Serb. We haven’t spoken in three years. But war… war doesn’t care who we used to be.”

Aida looked at the envelope again. It felt like a stone in her palm. Heavy with history.

“I’ll see what I can do,” she said finally, hiding the letter beneath the lining of her coat.

When she returned home hours later, her mother was boiling a tin can of tomato paste with water—soup. Emir sat on the floor reading a torn comic book by candlelight.

“Busy day?” Sabina asked.

Aida nodded and handed over the sugar cubes. “Two repairs. And... someone asked me to deliver something.”

Her mother looked up sharply. “What kind of something?”

“A letter. Across the line.”

Sabina’s jaw tightened. “Aida…”

“I didn’t say yes,” she lied. “But what if it’s important?”

Sabina didn’t answer. She simply stirred the watery soup and turned her back.

That night, as gunfire echoed like thunder, Aida sat in the dark with the envelope still hidden in her coat. She couldn’t sleep.

The streets were empty. But her thoughts were full.

Chapter 4 – Sewing for Survival

By the fourth week of the siege, bartering became the city’s new currency—and Aida’s sewing skills were more valuable than money.

There were no more paychecks. No deliveries. No supplies. The banks were closed, and the shelves in every market had been stripped bare within days. But everyone still had clothes. Torn jackets. Ripped sheets. Dresses too loose from the weight lost to hunger. And Aida could fix them all.

Each morning, she bundled herself in wool layers and carried her sewing kit like a soldier might carry ammunition. In a way, it was. Her needle, her thread, her scissors—these were her weapons against despair.

The front room of the apartment had become her new workspace. The windows were taped to keep from shattering, but you could still see daylight slice through the cracks. Sabina had moved the old Singer sewing machine there, setting it beside a rickety table stacked with mending jobs. The hum of the pedal was familiar. Soothing.

Today, Aida was stitching the arm back onto a child’s teddy bear, its fur matted from dirt and ash. The girl who owned it had traded a tin of sardines and half a candle. Aida didn’t ask questions anymore. She just sewed.

She paused to flex her fingers. The cold made her joints ache. Her needles bent more easily now—they were all secondhand or rusted. Still, the rhythm of sewing grounded her.

Across the room, Emir drew tanks in the margins of a blank notebook. He’d stopped asking about their father. Stopped asking when the power would come back, or if school would ever reopen.

“Do you think God can see us from here?” he asked suddenly.

Aida looked up from her stitching. “Why?”

He shrugged. “Because everything’s dark. Even in the day.”

She crossed to him and sat by his side. “God sees everything,” she said softly. “Even in the dark.”

He nodded without really believing, then returned to his drawings.

A knock at the door broke the silence. Sabina opened it cautiously, revealing a man wrapped in a military jacket too large for him. His eyes were red-rimmed, his hands shaking.

“My wife said you mend things,” he said to Aida. “I have something that needs hiding.”

She blinked. “Hiding?”

He reached into his jacket and produced a sealed envelope and a small pill bottle. “This needs to get to the clinic near the cathedral. If the Chetniks find it on me, I’m dead. But if you… if you sew it into something, maybe I can get through.”

Aida hesitated.

“You don’t have to come with me,” he said. “Just make it so they don’t see.”

She nodded slowly and reached for a folded scarf on the table. She turned it inside out and began stitching a false seam along one edge. The envelope fit perfectly beneath the lining, and the bottle tucked neatly inside a small hidden pocket.

As she worked, the man watched her with something close to reverence. “People think soldiers win wars,” he murmured. “But it’s women like you. The ones who make things possible.”

Aida didn’t respond. She was too busy concentrating. One stitch, then another, then another.

When she finished, she handed him the scarf and nodded toward the door. “Stay off the main roads. Move with the crowds if you see any.”

He offered a shaky smile. “Thank you.”

After he left, Sabina sat beside Aida.

“You’re going to get yourself killed,” she said quietly.

“Then I’ll die doing something that matters,” Aida replied.

Her mother looked away. “You’re too young to talk like that.”

Aida didn’t feel young anymore.

That night, as the city trembled under another round of shelling, Aida sat by the window with her needle and a small strip of cloth. She began to stitch a pattern from memory—something her grandmother taught her, long ago. A protective symbol sewn into linings and hems, for luck. For life.

Outside, Sarajevo burned.

Inside, Aida sewed on.

Chapter 5 – A Request in Code

It was late afternoon when the knock came—three short taps, a pause, then two more. The signal.

Aida opened the door to find Lejla, a young woman from the building next door. Her scarf was pulled tight around her face, but her green eyes were unmistakable—nervous, darting behind her like she expected to be followed.

“I need something stitched,” she said quickly, pushing past Aida into the apartment.

Sabina looked up from the stove, where she stirred boiled cabbage with the end of a wooden spoon. Emir sat silently nearby, poking at a torn book with a pencil stub.

Lejla unwrapped a bundle from under her coat—a men’s jacket, wool, slightly frayed at the cuffs.

“It’s not for me,” she whispered. “Can we talk alone?”

Aida nodded and led her into the bedroom.

Once the door closed, Lejla turned, her voice barely above a breath. “The resistance needs help. They’re trying to move messages past the Serbian patrol near Koševo. We need someone who can sew in… special compartments. Small things. Folded paper. Coordinates.”

Aida didn’t speak. Her fingers clenched slightly around the hem of the coat.

“We’ve seen your work,” Lejla continued. “The scarf last week. That wasn’t just a hem.”

Aida’s pulse quickened. “Who saw it?”

“Enough to trust you,” Lejla said. “We’re careful, Aida. But we need people like you.”

“What’s in the message?”

Lejla hesitated. “I don’t know. Only the runner knows. You just sew it into the coat lining. That’s all.”

Aida turned the jacket over in her hands. It was too big for a civilian. Military, maybe—an old uniform repurposed for someone trying to blend in. Her fingers found the inner seam beneath the left lapel. Loose enough to be unpicked and resewn without notice.

“You’ll have it by morning,” she said finally.

Lejla exhaled, relieved. “Good. Someone will come by to pick it up before dawn.”

After she left, Aida returned to the kitchen, her face unreadable.

“What did she want?” Sabina asked.

“A coat mended,” Aida lied.

Her mother studied her closely, but didn’t press. There were new rules now. Don’t ask. Don’t speak unless necessary. Truth had become a dangerous thing.

That night, as the city shivered under another blanket of darkness, Aida worked by candlelight. She turned the coat inside out and carefully opened the seam. Then, from her sewing kit, she removed a folded square of rice paper Lejla had handed her. It was thin, nearly weightless, but scrawled with tiny lines and symbols.

She didn’t try to read it.

Instead, she slid the paper between layers of lining, added a second stitch pattern to disguise the alteration, and sewed it shut.

Every movement was careful. Quiet. She couldn’t afford a mistake.

When she finished, she smoothed the coat flat and whispered a silent prayer over it.

Just before sunrise, a soft knock sounded on the door—two taps, one long pause, then two more. Aida answered, handing the jacket to a boy no older than fourteen. His eyes were sunken from hunger, but his shoulders were squared with something harder than youth.

He said nothing. Just took the coat and vanished.

Sabina entered the room as Aida closed the door.

“You’re part of it now,” her mother said quietly.

Aida turned. “What do you mean?”

“I’ve seen that look before. In your father’s eyes. Before he disappeared.”

For a long moment, neither spoke. Outside, a single gunshot cracked through the morning calm.

“I won’t let them use me,” Aida said finally.

Sabina’s eyes welled with quiet tears. “No, my daughter. You’ll use yourself. And that’s more dangerous.”

Chapter 6 – Checkpoint Tension

By mid-morning, Aida was threading her way through Sarajevo’s skeletal streets again, the cold cutting through her layers like broken glass. The sky was gray and low, promising more snow. She kept her satchel tight under one arm, her sewing kit tucked beneath layers of fabric like contraband.

Today’s errand was simple on the surface—deliver a mended shawl to a widow in the Hrid district. But the real test came halfway there: a checkpoint manned by Serbian soldiers, newly posted along a stretch of Vojvode Putnika Street. It had gone up just three days ago. Rumor was they were inspecting everything now—papers, bags, even people.

Aida had no choice but to go through it.