3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Digital Deen Publications

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

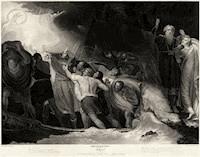

The Tempest is a comedy written by William Shakespeare. It is generally dated to 1610-11 and accepted as the last play written solely by him, although some scholars have argued for an earlier dating. While listed as a comedy in its initial publication in the First Folio of 1623, many modern editors have relabelled the play a romance.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

The Tempest

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare (baptised 26 April 1564 – died 23 April 1616) was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon" (or simply "The Bard"). His surviving works consist of 38 plays, 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and several other poems. His plays have been translated into every major living language, and are performed more often than those of any other playwright. Shakespeare was born and raised in Stratford-upon-Avon. At the age of 18 he married Anne Hathaway, who bore him three children: Susanna, and twins Hamnet and Judith. Between 1585 and 1592 he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part owner of the playing company the Lord Chamberlain's Men, later known as the King's Men. He appears to have retired to Stratford around 1613, where he died three years later. Few records of Shakespeare's private life survive, and there has been considerable speculation about such matters as his sexuality, religious beliefs, and whether the works attributed to him were written by others. Shakespeare produced most of his known work between 1590 and 1613. His early plays were mainly comedies and histories, genres he raised to the peak of sophistication and artistry by the end of the sixteenth century. Next he wrote mainly tragedies until about 1608, including Hamlet, King Lear, and Macbeth, considered some of the finest examples in the English language. In his last phase, he wrote tragicomedies, also known as romances, and collaborated with other playwrights. Many of his plays were published in editions of varying quality and accuracy during his lifetime, and in 1623 two of his former theatrical colleagues published the First Folio, a collected edition of his dramatic works that included all but two of the plays now recognised as Shakespeare's. Shakespeare was a respected poet and playwright in his own day, but his reputation did not rise to its present heights until the nineteenth century. The Romantics, in particular, acclaimed Shakespeare's genius, and the Victorians hero-worshipped Shakespeare with a reverence that George Bernard Shaw called "bardolatry". In the twentieth century, his work was repeatedly adopted and rediscovered by new movements in scholarship and performance. His plays remain highly popular today and are consistently performed and reinterpreted in diverse cultural and political contexts throughout the world.

Act I

SCENE I. On a ship at sea: a tempestuous noise of thunder and lightning heard.

Enter a Master and a Boatswain

Master

Boatswain!

Boatswain

Here, master: what cheer?

Master

Good, speak to the mariners: fall to't, yarely, or we run ourselves aground: bestir, bestir.

Exit

Enter Mariners

Boatswain

Heigh, my hearts! cheerly, cheerly, my hearts! yare, yare! Take in the topsail. Tend to the master's whistle. Blow, till thou burst thy wind, if room enough!

Enter ALONSO, SEBASTIAN, ANTONIO, FERDINAND, GONZALO, and others

ALONSO

Good boatswain, have care. Where's the master? Play the men.

Boatswain

I pray now, keep below.

ANTONIO

Where is the master, boatswain?

Boatswain

Do you not hear him? You mar our labour: keep your cabins: you do assist the storm.

GONZALO

Nay, good, be patient.

Boatswain

When the sea is. Hence! What cares these roarers for the name of king? To cabin: silence! trouble us not.

GONZALO

Good, yet remember whom thou hast aboard.

Boatswain

None that I more love than myself. You are a counsellor; if you can command these elements to silence, and work the peace of the present, we will not hand a rope more; use your authority: if you cannot, give thanks you have lived so long, and make yourself ready in your cabin for the mischance of the hour, if it so hap. Cheerly, good hearts! Out of our way, I say.

Exit

GONZALO

I have great comfort from this fellow: methinks he hath no drowning mark upon him; his complexion is perfect gallows. Stand fast, good Fate, to his hanging: make the rope of his destiny our cable, for our own doth little advantage. If he be not born to be hanged, our case is miserable.

Exeunt

Re-enter Boatswain

Boatswain

Down with the topmast! yare! lower, lower! Bring her to try with main-course.

A cry within

A plague upon this howling! they are louder than the weather or our office.

Re-enter SEBASTIAN, ANTONIO, and GONZALO

Yet again! what do you here? Shall we give o'er and drown? Have you a mind to sink?

SEBASTIAN

A pox o' your throat, you bawling, blasphemous, incharitable dog!

Boatswain

Work you then.

ANTONIO

Hang, cur! hang, you whoreson, insolent noisemaker! We are less afraid to be drowned than thou art.

GONZALO

I'll warrant him for drowning; though the ship were no stronger than a nutshell and as leaky as an unstanched wench.

Boatswain

Lay her a-hold, a-hold! set her two courses off to sea again; lay her off.

Enter Mariners wet

Mariners

All lost! to prayers, to prayers! all lost!

Boatswain

What, must our mouths be cold?

GONZALO

The king and prince at prayers! let's assist them, For our case is as theirs.

SEBASTIAN

I'm out of patience.

ANTONIO

We are merely cheated of our lives by drunkards: This wide-chapp'd rascal—would thou mightst lie drowning The washing of ten tides!

GONZALO

He'll be hang'd yet, Though every drop of water swear against it And gape at widest to glut him.

A confused noise within: 'Mercy on us!'— 'We split, we split!'—'Farewell, my wife and children!'— 'Farewell, brother!'—'We split, we split, we split!'

ANTONIO

Let's all sink with the king.

SEBASTIAN

Let's take leave of him.

Exeunt ANTONIO and SEBASTIAN

GONZALO

Now would I give a thousand furlongs of sea for an acre of barren ground, long heath, brown furze, any

SCENE II. The island. Before PROSPERO'S cell.

Enter PROSPERO and MIRANDA

MIRANDA

If by your art, my dearest father, you have Put the wild waters in this roar, allay them. The sky, it seems, would pour down stinking pitch, But that the sea, mounting to the welkin's cheek, Dashes the fire out. O, I have suffered With those that I saw suffer: a brave vessel, Who had, no doubt, some noble creature in her, Dash'd all to pieces. O, the cry did knock Against my very heart. Poor souls, they perish'd. Had I been any god of power, I would Have sunk the sea within the earth or ere It should the good ship so have swallow'd and The fraughting souls within her.

PROSPERO

Be collected: No more amazement: tell your piteous heart There's no harm done.

MIRANDA

O, woe the day!

PROSPERO

No harm. I have done nothing but in care of thee, Of thee, my dear one, thee, my daughter, who Art ignorant of what thou art, nought knowing Of whence I am, nor that I am more better Than Prospero, master of a full poor cell, And thy no greater father.

MIRANDA

More to know Did never meddle with my thoughts.

PROSPERO

'Tis time I should inform thee farther. Lend thy hand, And pluck my magic garment from me. So:

Lays down his mantle

Lie there, my art. Wipe thou thine eyes; have comfort. The direful spectacle of the wreck, which touch'd The very virtue of compassion in thee, I have with such provision in mine art So safely ordered that there is no soul— No, not so much perdition as an hair Betid to any creature in the vessel Which thou heard'st cry, which thou saw'st sink. Sit down; For thou must now know farther.

MIRANDA

You have often Begun to tell me what I am, but stopp'd And left me to a bootless inquisition, Concluding 'Stay: not yet.'

PROSPERO

The hour's now come; The very minute bids thee ope thine ear; Obey and be attentive. Canst thou remember A time before we came unto this cell? I do not think thou canst, for then thou wast not Out three years old.

MIRANDA

Certainly, sir, I can.

PROSPERO

By what? by any other house or person? Of any thing the image tell me that Hath kept with thy remembrance.

MIRANDA

'Tis far off And rather like a dream than an assurance That my remembrance warrants. Had I not Four or five women once that tended me?

PROSPERO

Thou hadst, and more, Miranda. But how is it That this lives in thy mind? What seest thou else In the dark backward and abysm of time? If thou remember'st aught ere thou camest here, How thou camest here thou mayst.

MIRANDA

But that I do not.

PROSPERO

Twelve year since, Miranda, twelve year since, Thy father was the Duke of Milan and A prince of power.

MIRANDA

Sir, are not you my father?

PROSPERO

Thy mother was a piece of virtue, and She said thou wast my daughter; and thy father Was Duke of Milan; and thou his only heir And princess no worse issued.

MIRANDA

O the heavens! What foul play had we, that we came from thence? Or blessed was't we did?

PROSPERO

Both, both, my girl: By foul play, as thou say'st, were we heaved thence, But blessedly holp hither.

MIRANDA

O, my heart bleeds To think o' the teen that I have turn'd you to, Which is from my remembrance! Please you, farther.

PROSPERO

My brother and thy uncle, call'd Antonio— I pray thee, mark me—that a brother should Be so perfidious!—he whom next thyself Of all the world I loved and to him put The manage of my state; as at that time Through all the signories it was the first And Prospero the prime duke, being so reputed In dignity, and for the liberal arts Without a parallel; those being all my study, The government I cast upon my brother And to my state grew stranger, being transported And rapt in secret studies. Thy false uncle— Dost thou attend me?

MIRANDA

Sir, most heedfully.

PROSPERO

Being once perfected how to grant suits, How to deny them, who to advance and who To trash for over-topping, new created The creatures that were mine, I say, or changed 'em,