7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

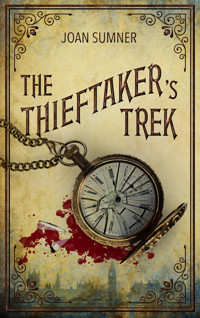

- Herausgeber: Bastei Entertainment

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Murder. Abduction. An attic full of frightened children.

London, 1810. The industrial revolution roars across England like a steam locomotive. Cotton mills and factories rake in profits thanks to cheap labor. Not from illicit African slave trade—but by enslaving little children.

When young Harry is lured from home with a penny, he can hardly believe his luck. Now he can help his widowed mother put food on the table. But Harry doesn't return home. Just another victim from the slums. Until Peter Frobisher takes on the case.

Frobisher has his own dark past. He's a 'thief taker,' a bounty hunter of sorts. He tracks down criminals for a living, so finding a child should be easy. But the more Frobisher unravels, the more sinister the reality becomes. The trail leads Frobisher away from the city, onto the English canal network, and beyond to Derbyshire.

When a dead body turns up, what started as a missing child case becomes a hunt for survival.

Author Joan Sumner spins adventure and mystery into The Thief Taker's Trek—a meticulously researched tale of London's industrial boom and the dark side of prosperity.

About the Author

Joan Sumner, MBA (Dundee)and Fellow of Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, has a working background across the private, public, and voluntary sectors. Semi-retired, she has settled in Midlothian, Scotland to write, closer to family and friends.

An award winning historical novelist, Joan formerly contributed self-help articles to a national weekly. Her travel abroad articles and occasional BBC radio contributions mostly starred her vintage MGB car.

Joan's small garden hosts a family of hedgehogs, giving enjoyment to everyone she knows! She is a member of the Society of Authors, the Edinburgh Writers’ Club, and the National Trust for Scotland. She paints, plays tennis and golf, and loves to travel - particularly by car.

But her passion is weaving mystery stories around little known historical facts.

Author Website: www.joansumner.com

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 415

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE BOOK

London, 1810. The industrial revolution roars across England like a steam locomotive. Cotton mills and factories rake in profits thanks to cheap labour. Not from illicit African slave trade-but by enslaving little children.

When young Harry is lured from home with a penny, he can hardly believe his luck. Now he can help his widowed mother put food on the table. But Harry doesn’t return home. Just another victim from the slums. Until Peter Frobisher takes on the case.

Frobisher has his own dark past. He’s a ‘thieftaker,’ a bounty hunter of sorts. He tracks down criminals for a living, so finding a child should be easy. But the more Frobisher unravels, the more sinister the reality becomes. The trail leads Frobisher away from the city, onto the English canal network, and beyond to Derbyshire.

When a dead body turns up, what started as a missing child case becomes a hunt for survival.

Author Joan Sumner spins adventure and mystery into The Thief Taker’s Trek—a meticulously researched tale of London’s industrial boom and the dark side of prosperity.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joan Sumner, MBA (Dundee)and Fellow of Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, has a working background across the private, public, and voluntary sectors. Semi-retired, she has settled in Midlothian, Scotland to write, closer to family and friends.

An award winning historical novelist, Joan formerly contributed self-help articles to a national weekly. Her travel abroad articles and occasional BBC radio contributions mostly starred her vintage MGB car.

Joan’s small garden hosts a family of hedgehogs, giving enjoyment to everyone she knows! She is a member of the Society of Authors, the Edinburgh Writers’ Club, and the National Trust for Scotland. She paints, plays tennis and golf, and loves to travel—particularly by car.

But her passion is weaving mystery stories around little known historical facts.

Readers can connect with Joan on social media:

Web: www.joansumner.com

Twitter: @JoanSumner_2018

JOAN SUMNER

»be« by BASTEI ENTERTAINMENT

Digital original edition

»be« by Bastei Entertainment is an imprint of Bastei Lübbe AG

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. This book is written in British English.

Copyright © 2018 by Bastei Lübbe AG, Schanzenstraße 6-20, 51063 Cologne, Germany

Written by Joan Sumner

Edited by Ray Banks, Al Guthrie

Project management: Lori Herber

Cover illustrations © thinkstock: DavidMSchrader | krzych-34 | Sirichoke | goir | Christine Zalewski | Ivan Kmit; © iStock: LoveTheWind

Cover design: Guter Punkt, München | www.guter-punkt.de

Map design: Lara Grabowski; illustrations © shutterstock: Color Symphony | In-Finity | LDDesign

E-book production: Dörlemann Satz, Lemförde

ISBN 978-3-7325-4802-6

www.be-ebooks.com

Twitter: @be_ebooks_com

For Rebecca

...for her unwavering faith and encouragement in my work

Michael's Map

CHAPTER 1

Even though he was only little, Harry knew when things were bad. First there was the letter, then Ma shouted at him about the milk, and then the man called Watkins came. The landlord had banged on the door after Ma shut and locked it, shouting words Harry wasn’t supposed to know.

She’d sat with her arms crossed on the table, put her head down and started to cry. Ma didn’t yell like his baby sister Meg – all loud and red. His mother’s tears just dropped on her hands without making a sound and her shoulders shook.

It frightened him.

Harry cuddled into her side, like she sometimes did to make him feel better, but she pushed him away without looking. Ma was probably still angry about the milk but he didn’t know what to say. Everything was different since his little sister had come.

It was better when Pa was here.

Harry wiped the floor with the mop. Ma stopped crying when he finished but her head was still down on the table and she looked asleep.

He wanted to go out to play but knew better than to leave without her say-so. He stopped watching her and kept quiet, batting a paper ball with a bit of stick in front of the fire where the pot was hung for supper.

When Ma finally raised her head, red-eyed, she made him promise never to go anywhere with Watkins.

“Cross my heart and hope to die,” he swore, but didn’t know what it meant. It was what his big brother George said when he was serious. Harry didn’t want to leave his friends and go up to live with Jesus but Ma looked happier.

She got up from the table. She emptied hot water from the kettle into the basin and started to wash the breakfast plates. Ma was staring out of the window above the sink at the tiny backyard beyond. He stood on his stool but couldn’t see anything worth looking at outside.

“Wiped those drips off the dresser?”

“Yes, Ma.”

“Boots.” She pointed at Harry’s feet. “You’ll need to go back to Betty and see if Daisy’s still got milk for the baby. Ask for just a little. Take a coin off the table and don’t forget to bring back the change.”

He was glad to escape.

He clattered up the cobbles to where their lane met the High Street and the cow.

Betty was sitting on her three-legged stool, dark hair and pink cheek resting on Daisy’s soft side, as her hands pulled on the dugs in turn, squirting milk into a jug.

“Back again?” asked Betty.

“I spilled it all.” Harry handed over his empty can. “Ma’s angry. Need just a little bit more from Daisy for the baby.”

“Well, let’s have a go. You’d best go and ask her nicely.”

“Daisy,” he called to the cow that gazed down at him. “Please can you give us a bit more for Meg?”

“It’s working, Harry! Don’t forget to thank Daisy.”

“You’re the bestest cow in all London.” He beamed and, when Daisy dipped her head and gave a short deep low, Harry patted her long face. “How much, Betty?”

“This one’s a present from Daisy to little Meg. Just get it home careful.”

“Ta, Betty.”

Harry carried the milk slowly over the slippery cobbles, holding the coin tight in his hand and hoping it would make his mother nice again.

“Ho there, Harry!”

Harry slowed and grinned at the man standing at the entrance to their street. “Can’t stop now, mister.” He burst through the door and laid the coin on the table. “Ma, Daisy gave it to Meggie as a present!”

“We’ll say no more about it then,” said Ma, putting Meg in her cradle, then she pulled him close in a gentle hug. “Good job it didn’t hit the mending! I’ll take the basket up to Mrs Jones and then I need to have a quick word with Widow Turner. Don’t you go opening the door to anyone.”

“Yes, Ma.”

“Be a good boy and watch the baby. She should sleep until I get back.”

After his mother left, Harry got out his slate and chalk and practised his letters and numbers. Meg snoozed. A while later he climbed onto a chair to reach for the family Bible on the dresser but the shelf was too high.

He noticed the letter lying lower down. It was opened but that didn’t interest him. He wanted to copy the fancy writing on the outside. Wiping off his slate, he tried to match the words. It wasn’t easy to make out what all the words meant.

He recognised Bisset and chalked his version as Harry Bisset just like Ma had showed him. He cleaned the slate and copied his name lots more times, wondering how long his mother would be.

When he got tired of copying the words, he put the letter back on the dresser and decided to draw the little elephant Pa had brought him from India.

When Ma came in, she looked at his picture and burst into tears. He dashed over and threw his arms round her legs.

“Don’t cry, Ma. What’s wrong? I been good, honest!”

“Oh, Harry,” she said. “It’s not you. I’m being silly, that’s all. Let’s have a cup of tea. I bought us a biscuit to share as a treat.”

He rushed to get the mugs and carefully carried their precious bowl of sugar to the table as Ma filled the teapot. They ate the biscuit with their tea, taking tiny bites to make it last as long as possible.

Harry looked at the change on the table. “Can I count it?”

Ma nodded. “Fetch down the old baccy pouch.”

He always had fun doing this. He upturned the ‘rainy-day’ bag and, as usual, sniffed the nutty smell of tobacco left in Pa’s empty canvas wrapper.

There weren’t as many coins as usual but he put all the farthings, ha’pennies, pennies and the very few silver coins into separate heaps. Harry added Ma’s mending money and counted how many coins were there.

His mother, slowly sipping her second cup of very weak tea, seemed to be dreaming before she did her own count.

But something was different. When the others came home for their midday meal, Ma sat down at the table instead of ladling the turnip broth straight away.

“More news, my lovies.” Ma sounded choked. “A letter came to say Pa’s got another medal coming soon and there’s a bit about the widows’ pension.”

“What good’s a medal now he’s dead?” Liza, his middle sister, kicked the table leg, tears streaming down her face. “I just wanted him safe home.”

“So did we all, lovey. So did we all.” Ma was rubbing her hand back and forward on the rough surface of the table. “I talked to one of the widows this morning and she told me how the pensions work. It’s not always the same amount, nor given regularly because it comes from donations, not from the army.”

“What’s donations mean?” Harry was pleased he’d got his question in before anyone could stop him.

“It means we’re not out of the woods yet, Harry, and we still need to be very careful with money. All the families of soldiers that died can get a share of the money collected from rich people,” Ma said. “But how much we get is worked out on how much the wealthy hand over each month. Trouble is there’s more and more widows after every battle.”

“It’s a bit like trying to cut up an apple so everyone’s got equal shares,” explained Martha, his biggest sister.

“It’s lucky Sir Gilbert’s been helping with the hampers, but we have to sort this out for ourselves.” His mother’s face went a bit pink. “So, we must keep quiet about it and not bother Mr Harper if he’s sent to see us.”

Harry looked at each face in turn. They were gazing into space, except his mother. She stared at the letter on the table. Eventually she folded it and got up to serve the meal. Quietly, they ate their soup before going back to work.

Then Jimmy arrived with his wooden sword and the ball his sailor father had given him and Harry was allowed to go out to play in the courtyard. His mother gave him the milk can and a coin for Daisy’s evening milking.

They had a sword fight until the other boys came out for a game with the ball.

“Look, Harry! That big fellow’s back. Wonder why he’s allus hanging round here.”

“Probably waiting for somebody.” Harry scarcely looked at the large man leaning against the vennel wall. His attention was fixed on the ball. “Watch out, Jimmy, or they’ll win!”

Their game didn’t need any rules; it was a way to play outside and still keep warm. Harry had already taken off his coat, making sure the coin was in his pocket. He was easy to spot in his colourful striped pullover.

“Ma asked me about him last night,” panted Jimmy. “I think she’s going to find out what he’s doing here. He seems to watch you most.”

“Cause I’m bestest! But I gotta go and get the milk. Won’t be long, so try and keep the ball till I gets back.”

Harry picked up the milk can from beside his coat and retrieved the coin. He glanced at the big man and saw him looking up and down the vennel, moving farther into the short tunnel as if he was checking on something.

Harry had spoken to the stranger a few times when out to play so he was almost a friend, although the man didn’t seem to bother calling over any of the others. He’d even asked Harry his name and which cottage was his.

It was beginning to get dark and Harry knew he should have got the milk earlier but their side was winning. He hurried towards the High Street, almost bumping into the big man inside the tunnel.

CHAPTER 2

The Big Man smiled cheerfully. “Having a good game today, Harry?”

“Can’t talk, mister. Got to get milk for the baby and we’s won the ball so I gotta be quick.”

“You know, Harry, I’m seeking a bright nipper. How’d you like to get a shiny penny doing a little job for me?”

Harry gazed back at the ball game. But, still, a whole cartwheel! Ma could put it in their rainy-day pouch and she’d like him again. He grinned and nodded. He was only five but he always said he was nearly six. Of course, he was big enough to earn the coin.

The Big Man’s smile was a bit different and he took Harry’s arm to pull him into the shadowed side of the vennel, hiding him from the cottage door.

“What sort of job is it, mister?” Happy to be singled out, Harry turned and waved back to his playmates.

“Put the can down just now and come away up the alley, little’un, so I can tell you all about it…”

“Ma’ll be angry if I’m late.” Harry hung back.

“It’ll only take a little while.” The man tightened his grip, urging Harry round the corner into the High Street.

Harry saw Betty smile at him.

The Big Man took the coin and held on to Harry, making him walk fast, almost running. Harry saw himself in the dirty glass of a shop window, trying to keep up.

***

The man’s building wasn’t all that far from home. Harry climbed the rickety outside stair far up off the ground and walked into a lantern-lit room where a woman was sitting. The Big Man lifted him up through a hole into a dark attic.

Harry saw ghostly shapes. He got scared. He tried to go back down but the Big Man pushed him up and a cold hand pulled him into the dim space.

“Easy does it.” A boy’s voice. “Sit down by the wall while the food’s doled out.”

“Who’re you?”

“Tom.”

“I’m Harry.”

“Just stay put till Piper closes the hatch.”

He saw children, lots of children, on their hands and knees round the open hatch, light shining up onto their faces. It was quiet when the lid fell.

Tom brought a piece of bread. “You’ll get used to it. The straw’s for sleeping in and there’s a bucket for us to use, see, by the hatch. We gets to eat morning and night. This weather, it’s better than a doorway.”

Harry’s throat was tight and the bread was dry. “Can’t eat it. You want it?”

He felt fingers lifting the food from his hand.

“Don’t want to waste it and there’s rats, big ones, that come out at night.”

That night, Harry tried to burrow down in the smelly straw like Tom showed him but he couldn’t sleep.

It was too cold. It was dark. He was hungry.

Harry didn’t know what was happening to him. He tried to pull the straw together and rolled over with it, like a blanket, hot tears running down his cheeks. Talking to the Big Man was a big mistake. Ma was going to be angry when she came for him.

She’d get his big brother to help and they would find him. He cried himself to sleep in the rustling blackness.

***

Harry woke to the sound of movement through the straw towards the hatch when the morning feed was pushed up. Grey dawn filtered through the gaps in the roof and he could see the others crouched around the closed hole in the floor. He crept behind them and wondered which one was Tom.

“No more than two swallows each,” an older boy warned softly as the flagon of water went round. “We don’t know when we’ll get more.”

Perhaps the boy was afraid the Big Man was listening below. After a short time, Harry heard a door shut. Breaths were let go in the attic and he guessed he’d been right.

“Why’s we here? I want my ma. Who’s Tom?” Harry was scared.

“I’m Tom. Not got a ma or pa. The big geezer picked me up from me corner.”

“What’s he called?”

“Mr Piper’s the bloke what brought you,” said Tom.

Harry nodded over his mouthful of bread, desperate for his two swallows. “What’s he want me for?”

“Dunno. Johnnie’s been here longest, he might know,” Tom whispered and Harry felt the boy’s breath on his ear. “Johnnie says Piper’s brought others, regular like, that’s already gone.”

“There’s lots here,” said Harry. “What about that little boy?”

“I can count to ten. There’s more than that here,” Tom boasted. “That one’s Sid. Not sure why Piper brought such a wee nipper.”

Harry heard the others’ stories and Tom told him their names. There were several bigger than Harry but none as big as George and his sisters. When Harry asked, only a few knew how old they were.

“I was told to wait for my pa outside the gin palace,” said Susie, while several of the others nodded.

“What’s a gin palace?” Harry asked.

“It’s a place where people drink until they’ve no money or falls down drunk.”

“They’re smoky, too. And sometimes there’s fights,” added Alfie, hunched against the wall. “That’s when you sneak in and drain the glasses. That makes you feel better for a while.”

“But what happened to your pa, Susie?” Harry persisted. He could see she was dressed in odd clothes, her dirty hair tied back with what looked like a bootlace.

“Must’ve gone out the back way ’cause I never seen him no more.”

“Hope I never see our old woman again. She’d beat me for nothing.” Jane was bigger than the other girls. “One day, she was walloping me and I pushed a stool into her legs so she fell over. I ran out afore she could grab me again. Never went back.”

Harry felt bad. Ma worked so hard for them. He knew deep down that he was really lucky. She loved him, and she would come and get him out of this horrible place.

The others asked him questions. They wanted to know where he’d come from and how Piper had tricked him. Harry told them about the penny.

Tom asked him to tell them the whole story. Harry said it’d started with Piper promising the penny to show him the way to the next street.

“That’s what happened to me.” Susie nodded.

“He pulled me up our vennel and wouldn’t let go of my arm, saying we had to hurry. We passed the street he said he was looking for but he dragged me on, even though I said I wasn’t allowed to go any farther on my own.”

“Who tells you how far you can go?” asked Johnnie.

“Ma. She’s going to be cross and I missed supper, and it’ll make her crosser,” Harry continued. “He told me to stop whining or he’d get angry and I got scared. I asked him what he wanted me to do but he didn’t say nothing, just kept hauling me along making my boots slide against the cobbles.”

“That’s just what happened to me, though he picked me up and carried me,” said Susie, who was very thin.

“Lots of people saw us but when he slapped me for shouting for help, nobody did anything. Here’s not like home. The houses look all on top of each other with long stairs outside. I couldn’t see so I kept close to Piper, scared he’d leave me.”

“I can remember feeling like that. After Mum and Dad died, I ran away from the poorhouse and Piper told me he could find me a home,” said Johnnie. “I’ve been here for ages. He wouldn’t catch me like that now.”

“What else happened when you came last night?” Teeny was small and plumper than everyone else.

“There was a woman downstairs – a bit grumpy.”

“That’d be Ruth, Piper’s woman,” said Johnnie.

“I didn’t understand what they said to each other before he pushed me up here.”

“Tell us what he said and we’ll sort it out.”

“Piper told the woman something like ‘got him, sweet as a nut, but I don’t like the feel of this job’.”

“What did she say back?” asked Johnnie.

“Something like they could get the money and a bit more by selling me with the crew upstairs. Then the Big Man said, ‘What if they want proof?’”

“Proof of what?” asked Susie.

“Dunno. Don’t know what ‘proof’ is,” said Harry. “But she said they’d keep some clothes and say I’d gone in the river!”

There was a lot of muttering and then Johnnie decided they would think about it later. Tom showed Harry their morning routine. They took turns to use the empty bucket and then picked up the straw, tossing it in the air to dry and fluff it for the night. The group settled cross-legged on the boards against the opposite wall and asked Harry more, wanting to know about his home. He was the odd one out in the dusty, smelly loft. The way they looked at him showed Harry they thought he was soft to get caught, so he stopped talking.

Piper arrived with another boy, about Harry’s size.

The new boy was pushed into the loft and Piper took away the full bucket before locking the hatch. The latest arrival, called Colin, looked frightened as they gathered round him.

They split themselves by height into two groups and swapped life stories. It made Harry’s seem pretty tame. But he realised, hearing about his home was as interesting to them as their stories were to him.

“You got a ma and dad, Harry?” said Jane.

“Pa died in a big battle in Spain—”

“What’s Spain?” asked Alfie.

“It’s across the sea. They had to go there on a ship with all the horses and things. It’s a long way from Spitalfields but not as far as India where Pa was before.”

“Did he win the battle?”

“Yes. Pa’s a hero and we got his medal coming soon.”

Talking about his pa made Harry feel important and sort of made up for him not having to steal food like the others. The group huddled together in the chill.

“How come you’re here?” said Johnnie.

“Told you, trying to earn a penny for my ma,” said Harry.

“Gawd, you’re stupid! Gotta look out for tricks like that.”

“I’d seen him before, regular like, not like going off with a stranger.” Harry could feel himself getting red. “I’m not stupid.”

“So, clever clogs, how’d you get caught then?” sneered Johnnie.

“He asked me for directions.” Harry realised he’d been silly. He stared, daring them to say it.

“You got boots,” said Annie. “What you need a penny for?”

“When Pa died, the money stopped coming.”

“Not rich, then?”

“We got a house,” said Harry. “But rich people don’t worry about money like Ma does.”

“What’s she like?” Annie sat forward, elbows on the knees of her crossed legs. “Got brothers and sisters?”

“Ma’s nice, most of the time. She can read and write.”

Harry decided not to say he could too, in case they thought he was showing off. “Got a big brother and two big sisters. And now there’s the baby too. Meggie cries a lot.”

They made signs to tell them more.

“George and the girls go to work so I wants to help too. Ma’s started mending shirts and sheets to pay the rent. She has to do it before it’s washed and ironed so it don’t smell very nice.”

“What’s ironed?” asked Alfie.

“You wipes a clean shirt with a hot iron to make the cloth smooth and soft.” Harry made an iron shape with his hands.

“Mean like a blacksmith’s?”

“Dunno. What’s a blacksmith?” said Harry.

“It looks a bit like a shop with a fire in back to bend metal for horse’s shoes.”

“That’s called a farrier when it goes with the troops and horses. Our smoothing irons are flat on the bottom and heavy. We got two. Ma uses one and puts the other to heat over the fire, then she swaps.”

“Go back to what you said about them downstairs,” said Johnnie.

“Said I don’t know what they meant.”

“Tell us again, maybe we’ll know.”

“They could make more money than throwing me in the river by selling me with you.”

“Gawd,” said Tom. “Sounds like they meant to kill you.”

“Kill me?” squeaked Harry.

“Aye. But more important, we’re being sold,” said Johnnie.

“Any ideas about the buyer?” asked Jane.

“Who’d want us all?” said Tom.

“Maybe a big estate for working on the land,” said Johnnie.

“Sir Gilbert Milne’s got a big estate,” Harry remembered. “He’s a friend of ours.”

“Where is it?”

“It’s in the country and we went over the river. But there’s loads of children on the farms.”

“The country might be better. They’d have food,” said Tom.

“Being killed’d be worse than sold,” said Harry.

“Maybe to you,” said Johnnie.

Harry hoped that Ma would come soon.

The older boys had been bunching straw and tied it together with longer strands to start a game of catch. Harry played well, weaving between the older children and jumping to steal the bundle. They made the old floorboards shake.

Suddenly, the hatch flew open with a ferocious bang. A voice screeched at them. “What the bloody hell are you doing? I got enough to do without cleaning up after you lot. This floor won’t stand all of you dashing about. Sit down and keep quiet or I might forget to fill your basket tonight.”

The boys shuffled to the wall and sat down. The girls had been talking quietly and making little dolls from whatever bits of clean straw they could find. Ruth’s head disappeared as the string dragged the lid back over the hole.

There was silence. None of them wanted to risk being without the next meal.

“Looks like we need to get Harry to tell us another bit of his tale,” whispered Susie.

“Yes, peease,” said tiny Sid.

They tended to forget the infant was there but Harry looked round the others and saw them nodding. His tummy started to rumble and, as a stink floated across the straw, he realised Colin was using the bucket.

“My job with the mending Ma takes in is sorting out what bits need stitching or darning. I looks for holes or splits in the dirty stuff so that Ma can fix it before it goes to the washerwoman.”

“What’s darning?” said Tom.

“It’s filling in a hole in a stocking or something by working thread back and forward and almost making it part of the cloth,” explained Harry. “Most of it smells fusty as though it’s been lying wet in a heap but some of the collars smell nice. The shirts got long tails but they’re mostly black and pong real bad. Sometimes Ma has to shake out grubs from the sheets.”

“I always wanted to sleep in a bed with real sheets,” said Jane. “But if it’s going to be full of grubs, I’ve changed my mind.”

“My other job is picking up bread sold cheap at the end of the day. If I can, I wheedles the baker’s wife into letting me have a half-loaf that’s not too hard. Usually, by the time I gets home the turnip soup is nearly soft enough to eat and we each get two slices for dipping.”

Bert, one of the older boys, laughed. “Dipping here means picking pockets.”

“How d’you do that?” Harry asked.

Two of them got up and, one acting the thief and the other the victim, showed how it was done with a handful of straw. Tom said it was easier done in pairs with one pushing into the mark to lift a purse and the other distracting him.

Tom then showed them some variations of thieving. Practising was great fun though they were careful not to kick up any straw. By the time their food arrived, they had been sitting in the dark for ages and were cold.

After they’d finished eating they settled down in the straw and Harry thought about home. He dug deeper into the prickly stuff and as he drifted off, said his nightly prayers, asking Jesus to send Ma to rescue him soon.

CHAPTER 3

The black silk cap, gleaming squarely atop his white full-bottomed wig, was lifted from the judge’s head as he delivered the jury’s verdict. It was a hanging offence. The judge rose, bowed to the court and left.

The public gallery at the Old Bailey, London’s main criminal courthouse, broke into cheers and thumping of feet as the highwayman made a courtly bow before being led to the alley linking the courtroom to Newgate Gaol. As he passed Peter Frobisher, the thieftaker, the prisoner made a succinct and flagrant gesture towards his captor.

Frobisher’s case of theft with violence on the King’s highroad had taken minutes to prosecute and sentence. He collected his mandatory payment from the clerk and returned to push his papers into a black bag.

He was aware that lamps would soon be lit against the gloom of the winter afternoon, creating a dramatic backdrop of light and shadow in the courtroom. Felons, witnesses, judge and jury provided entertainment for the ticket-buying audience.

Peter Frobisher was not proud of his occupation but at graduation he had abandoned the pursuit of a slow career in engineering as his lover, Mary, was pregnant. They needed a steady income, so he used his talents to catch felons for prosecution. Tragically, Mary died in childbirth, bequeathing him a son. With an infant to feed, he had no choice but to work hard as a thieftaker to gain substantial and regular fees from the Crown for successful cases. He eased his instinctive distaste for the job by doing the thieftaker’s work fairly and with greater respect than many others of his kind.

Tall, muscular and fit, Frobisher looked like a sportsman. He had little memory of childhood beyond begging for food on the streets but, as an adult, he was thankful his mother had succumbed to a man who unknowingly provided his child with good physical characteristics. Regular training sessions in one of Bethnal’s boxing clubs put a classic touch to his strength and posture.

He shrugged into his well-tailored topcoat and felt a clap on his shoulder as he pulled down his cuffs. Turning, he smiled at his shorter friend.

“We should talk.” Benjamin Goldziher ran his hand over the fine cloth of Frobisher’s coat. “Something interesting has come up.”

Nobody of any importance had yet been sent to Newgate Gaol so the crowd was content to wait in the warmth, hoping for a salacious case. Other thieftakers, generalised as disreputable by the barrister Garrow, lounged by the entrance waiting their turn to prosecute captives.

Sly, surreptitious and scruffy, they whistled mockingly at Frobisher’s immaculate turnout and doffed their hats as he exited behind Goldziher. Ignoring them, he tracked the policeman through the crowd by his battered brown tricorne hat.

The Old Bailey was first built in 1673 against the ancient fortified walls of London, in close proximity to Newgate. It had been remodelled several times and now was secured behind a formidable brick wall. Its narrow entrance was designed to deter the entry of riotous mobs.

Frobisher followed Goldziher into the damp fog, and they turned left to weave their way towards Covent Garden.

“What’s it all about?” Frobisher asked.

“Let’s stop off at Arne’s.” Goldziher tapped the side of his nose. The slightly built detective worked as a principal officer in the Bow Street police office.

In Drury Lane, Arne’s sign, suspended above the coffee house, was barely visible from the pavement but the rich aroma of coffee and cigars hit them at the door.

Inside the coffee house, the lenses of Goldziher’s wire-framed spectacles instantly misted up in the warmth. The policeman removed the obscuring glasses, stopping at one side of the queue of impatient gentlemen and signalled to a man in a long white apron.

The waiter pointed at a small table near the fire.

“Free as usual, Ben,” said Frobisher. “But have a care with that umbrella stand…”

“Lead the way.” Goldziher dried his lenses on a pristine handkerchief.

“Afternoon, gents.” The waiter met them with a smile and a tray, wiping the table before setting down clean cups and a tiny bowl of sugar. “Anything to go with the coffee this morning, sirs?”

“Not at the moment, Roberts, thank you.” Goldziher removed his hat, revealing fair curly hair above lively blue eyes, a strong nose and high cheekbones.

Resettling his spectacles, he grinned across the table. “Just as well Bow Street often uses this place to think.”

“Tackling a knife-wielding scruff threatening Roberts for the tips box was beyond thought!”

“Must say, I even surprised myself.” Goldziher’s smile was modest.

“I’m amazed the damned thing’s still sitting by the queue. It’s simply asking for another attempt.”

“Hmm. Thought your case went well today.”

“Ignore me. Been feeling philosophical lately,” Frobisher said, watching the waiter arrive with a pot of coffee. “Unwise when dealing with the judiciary.”

Roberts poured half of the thick dark brew, then left them with the pot.

“Perhaps I can lift your spirits.” Goldziher handed over a newssheet and pointed to an advertisement. “That was placed yesterday but it’s garnered no response, despite the reward. Mr Harper came into the office today asking if we could help. Of course, the deskman had to tell him Bow Street doesn’t rescue lost children but I dropped your name as I passed.”

“Who’s this Harper?” Frobisher tapped the printed block and returned the paper.

“Sir Gilbert Milne’s man of business.”

“Never heard of him.”

“Minor gentry. House in Mayfair and country estate near Wimbledon village.” Goldziher leaned to one side to pull a pipe and tobacco pouch from his coat pocket. “Looks like a well-paying investigation in the offing—”

“Got another highwayman to pick up,” Frobisher muttered. “Forty pounds clear profit.”

“Milne’s willing to pay for a discreet and reliable thieftaker to find a kidnapped five-year-old. Why not let someone else take the robber? This is the sort of business you’ve been saying you want to do. Success with a baron will be worth more to your reputation and money than any amount of thieftaking.”

“You recommended me?”

“Of course not! Bow Street can’t be seen to favour individual thieftakers.” Goldziher began to pack his pipe with dexterity.

“Tell me about the missing child.” Frobisher added a little sugar to his cup before taking a satisfying sip of the strong hot brew, redolent of foreign parts and dark mysteries.

“Not certain, really. It’s strange… I can’t put my finger on it. The case sounds straightforward but there’s something intriguing, out of kilter.” Goldziher puffed steadily. “The agent, Harper, will doubtless have picked up your name if you call on him. He said his employer was acting on behalf of the child’s mother, a war widow.”

“Boy or girl?”

“Young boy from Spitalfields. Lost a couple of days ago. Your background makes you a natural for this one, Peter, and it’s local so you could let Michael get involved.”

“I’m trying to distract my son from his fascination with thieftaking.”

“You’ve heard from Cambridge?” Goldziher leaned forward enthusiastically. “He’s for university after the summer? Wonderful. And only just seventeen by then. Well done!”

“No. The results aren’t out yet, but Henry is optimistic. Michael’s already struck a bargain with him. So long as a good degree is in the offing, Henry’s agreed to let him work with me during the holidays. I’m not sure it’s a good idea – thieftaking is a dirty business.”

“Henry’s influence on you from childhood has been successful. It’s only natural for him to want a crack at your son.”

“I let my benefactor down with Mary’s pregnancy and, in some ways, getting married disappointed him more.” Frobisher gazed at his coffee; he sounded uncharacteristically melancholy.

“Nonsense,” Goldziher said. “You dealt with the situation honourably. Mary’s early death in childbirth might have quashed Henry’s ultimate ambitions for you but how many former street urchins gain not only an honours degree at an ancient university but win a boxing championship? Never doubt that Henry Inglis is proud of you, both of you. It shines out of the old man.”

“Maybe you’re right, Ben. Now that Michael’s immediate future is more or less settled, perhaps it’s time to move on and risk a business plan.” Frobisher finished his coffee, staring at the fire thoughtfully. “I’ll pursue the kidnapping case this afternoon and let you know how it goes.”

***

Frobisher mounted shallow steps to the front door and let the brass doorknocker drop with a clatter. Any connection between a widow woman living in Spitalfields and this house in Mayfair, seemed bizarre.

When a stately-looking butler answered, Frobisher presented his visiting card. “I should like to see Mr Harper.”

The butler’s bushy eyebrows rose at the name on the card and Frobisher realised that his reputation as a thieftaker had reached Mayfair or, at least, its lower orders.

“I will ascertain whether Mr Harper is available.”

Frobisher entered, removed his hat and upturned it to drop his leather gloves inside. The walls were panelled in lightly stained wood, which reflected daylight from the glass cupola. The oak staircase rose against a wall that held still-life paintings at regular intervals. A footman loitered, presumably to deter casual visitors from pilfering the objets d’art.

The thieftaker was announced into a substantial room, overlooking the street. It seemed to function as study, office, and library. Harper, a neat man dressed conservatively with his light brown hair brushed straight back, looked to be in his mid-thirties. He rose from behind a bright mahogany desk and indicated an armchair in front of the coal fire.

“Please, take a seat.”

Frobisher sat and waited.

“I gather you find people.” Harper took the chair opposite. “And that you have a solid reputation for fair dealing.”

“That’s reassuring to hear but what exactly is the issue?”

“Sir Gilbert Milne, my employer, seeks the return of an abducted child. He insists, however, on staying in the shadows.”

“I’m afraid I must be able to deal with him. There are details—”

“I’m in Milne’s total confidence,” said Harper. “I can supply all the information you need.”

“Very well,” said Frobisher. “But, in order to confirm that I am in a position to help your employer, I must first talk to the child’s mother.”

“Of course. This is Mrs Bisset’s address.” Harper handed him a note. “When do you intend visiting her?”

“Directly. Speed is critical in such cases.”

“I can take you, or do you prefer your own carriage?”

Frobisher was not about to admit to a wary client that the cost of taxing horses in town was beyond his means. His private enquiry business was a fledgling but, with a little financial prudence, it had the potential to fly high.

“Excellent.” Frobisher stood. “I shall have to ask fairly personal questions, so having you there to vouch for me would prove most helpful.”

CHAPTER 4

The drive took them from the tree-lined squares of Mayfair to the cobbled warrens and working lanes of Spitalfields, the runnels choked with household waste and rubbish from the market stalls. Acrid odours of the tanners and charcoal burners penetrated the comfortable carriage.

“What happened to Mrs Bisset’s husband?” asked Frobisher.

“Killed in Spain last summer,” said Harper. “She has two sons and three daughters, the youngest born after Bisset’s death. It’s her younger son, Harry, who is missing.”

“And her current situation?”

“She struggles financially, despite the older children working.”

“But surely she is entitled to a widow’s pension?”

“Wages from the army stopped once Bisset’s death was confirmed. The pension for army widows comes from charity, distributed by the Chelsea Hospital.” Harper seemed angry. “The amount varies in both frequency and amount. The poorhouse is an ever-present threat.”

“I was unaware of such difficulties.” Frobisher considered the situation further. “It’s unlikely, then, the child has been kidnapped for ransom. How does Sir Gilbert Milne fit into this?”

“Mrs Bisset’s father lives on Milne’s estate in Surrey. He has offered to finance the recovery of his tenant’s grandchild. There was no response to the reward information. Generously, he sanctioned a search.”

Harper knew little about the family, and Frobisher learned nothing more about the lost child. They walked to the row of cottages that comprised one side of a small courtyard.

A young woman answered Harper’s knock and stared hopefully at the agent. Harper shook his head. Her shoulders slumped.

“Sir Gilbert has enlisted Mr Frobisher to find little Harry.”

“Good day, ma’am.” Frobisher smiled at her. She gestured for them to come in. He removed his tall, dark blue beaver but still had to bend to enter the house. “Try to stay optimistic. I feel sure I’ll be able to find your son but I’ll need your assistance.”

“Of course, sir.” Mrs Bisset moved a pile of mending from a chair to a laundry basket on the floor. “Please, take a seat.”

Frobisher was surprised to see curtains and glazed windows instead of the usual cottage shutters. A small sofa dotted with brightly coloured cushions sat behind the front door. Two armchairs had been pushed back from the fireplace to accommodate a clothes horse, which was draped with shirts and towels.

The room displayed comfort at odds with the large basket of mending. A simple wooden cradle held her baby.

“Sir Gilbert is frustrated that he can do no more to help.” Harper put the provisions on the dresser and sat. “Now, if you would, please answer Mr Frobisher’s questions.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Very well,” said Frobisher indicating the table. “Tell me what happened from just before Harry went missing.”

She sat and took a deep breath as she recalled what was clearly a painful memory. “We’d had a bad morning that day. Harry spilt fresh milk on the floor when the landlord called.”

“Did the landlord upset you, ma’am?” Milne’s agent asked.

“Watkins has an unnatural interest in little Harry so I keep him out of the monster’s way.”

Harper swore, then apologised, looking embarrassed.

“Do you believe this man could have taken him?” said Frobisher.

“No. I’m sure not. I’ve told my son to come inside as soon as he sees Watkins doing his rounds. Harry’s only five but he’s generally obedient. And the other children would have said something before now.”

“What next?”

“I made Harry wipe up the milk while I answered the door.” Mrs Bisset started to weep, covering her face with her hands. “I dread that Harry went because he knew I was angry.”

“I raised a son on my own too, Mrs Bisset,” said Frobisher. “Things flare up but they pass. I believe it would take more than a ticking off to make him leave home.”

She smiled at him gratefully and glanced at Harper.

“Children are often very observant. What did the others say?” Frobisher asked.

“Not much.” She caught herself rubbing her hand against the grain of the table and stopped. “Just that Harry and his friend Jimmy had been playing outside until the others came out. A big man was in the lane to the High Street but they’d seen him before and assumed he was waiting for someone. The fellow spoke when Harry passed him with the milk can and they walked out through the vennel together.”

Frobisher looked up from his notes. “Why didn’t they tell you Harry had gone?”

“They knew it would get him into trouble.” She sighed. “Then the children got involved in their games and simply forgot about it until they were called indoors. It was getting dark and they spotted his coat. Little Jimmy came to bring it in and let me know.”

Frobisher persisted. “That’s all Harry’s friends said?”

“They just kept telling me the man was very big, but then they’re so small.” Tears filled her eyes.

“Can you give me a description of Harry?”

“Well. He’s bright. Tends to be the leader of mischief with him and Jimmy. Harry’s still on the short side, about this high.” She put her hand out at approximately forty inches. “But he’s strong for his age and a quick mover. He’s missing two front baby teeth—”

“Upper or lower?”

“One of each but the lower one is growing in, you can just see it shining through.” She hiccupped and bent her head. Harper went to pour a cup of water from the jug by the sink. She took a sip, a deep breath, and continued. “Sorry. His hair is lightish brown, ordinary and straight. His eyes are blue and sort of noticing things, if you know what I mean.”

He checked that she had already spoken about the abduction to the district’s voluntary constable, the milkmaid and local neighbours. Nobody had seen the little boy.

“Very well,” said Frobisher, rising from his seat. “I’ll send word whenever I have any news.”

As he was leaving, he glanced back to see Mrs Bisset easing her hand from under Harper’s before she unpacked the basket of provisions.

And the thieftaker wondered…

***

Frobisher returned to Spitalfields, bringing his son with him to draw rough portraits of Harry and the large man for their enquiries.

Leaning against the Bissets’ low front wall, Michael gathered a coterie of curious children. They wanted to see what he was sketching, and eagerly contributed details.

Jimmy raced home when he saw Frobisher lifting his hat to call on his mother. The little boy, staying close to her, was forthcoming so Frobisher took out his notebook, licked his pencil and asked the child about Harry’s disappearance.

“He was glad to be let out,” said Jimmy. “He’d been in trouble in the morning.”

“What did you do when he came out to play?”

“We was being army and navy with swords. Pa’s at sea fighting bad sailors, and Harry’s pa’s a soldier, so we takes turns to be Frenchies till all the others come out.” The little boy showed him two sturdy sticks with cross-bar handles. “This one’s Harry’s. See, he’s put his name on it!”

“Mrs Bisset said you were kicking a ball?”

“After the others came out.” Jimmy obviously thought Frobisher was a bit slow. “That’s when Harry took off his coat.”

“What did the big man look like?”

“He’s high, like you, but soft.” Jimmy closed his eyes and frowned. “He had a black hat. Proper hat with a brim all round, but flatter than yours.”

“How about his face? Thin or fat, big nose…?”

“Round and fattish. Don’t ’member his nose.”

“Clothes?” He gave the child time to think.

“Topcoat.” Jimmy’s eyes were still closed. “It’s green, I think. Heavy boots cause they were louder than Harry’s.”

“You’re doing really well, Jimmy.” Frobisher waved towards his son by the wall through the window. “D’you think you could tell Michael all that and see if he can draw faces that look like Harry and the stranger?”

“Yes, mister.” Jimmy moved out towards Michael, then he stopped. “You’ll bring Harry back?”

“Yes, Jimmy, I’ll find him. You’re the best witness I’ve ever had.” Frobisher rustled a poke of boiled sweets. The little boy twirled back to take one before rushing to talk to Michael and tell his friends.

“Well, Mr Frobisher, I hope that helped,” said Jimmy’s mother.

“A clear description always helps.”

“Harry’s real fond of his ma. Jenny worries he’s run away but it’s not how I read things. He’s been taken and now we’re all feared for our little ones. Never had nothing like this afore.”

He finished his notes and pocketed the book. “I’m obliged to you, ma’am. I’ll go and talk to some of the shopkeepers on the main street.”