Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

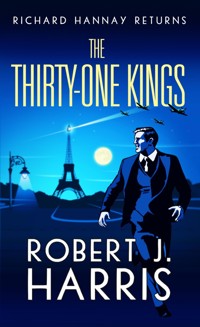

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: The The Richard Hannay Adventures

- Sprache: Englisch

June 1940. As German troops pour across France, the veteran soldier and adventurer Richard Hannay is called back into service. In Paris an individual code named 'Roland' has disappeared and is assumed to be in the hands of Nazi agents. Only he knows the secret of the Thirty-One Kings, a secret upon which the whole future of Europe depends. Hannay is dispatched to Paris to find Roland before the Germans overrun the city. On a hazardous journey across the battlefields of France Hannay is joined by old friends and new allies as he confronts a ruthless foe who will stop at nothing to destroy him. The lights are going out across Paris and time is running out for the world as both sides battle for the secret of the Thirty-One Kings.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 262

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE THIRTY-ONE KINGS

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Robert J. Harris 2017

The right of Robert J. Harris to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978 1 84697 391 8

eBook ISBN 978 0 85790 937 4

Design and typesetting by Studio Monachino

To the 78ers – my own personal Die-Hards

His thoughts had been dwelling on his reunion with friends. Those friends would all be scattered. Sandy Clanroyden would be off on some wild adventure. Archie Roylance would be flying, game leg and all. Hannay, Palliser-Yeates, Lamancha, they would all be serving somehow and somewhere.

JOHN BUCHAN, Sick Heart River

CONTENTS

PART ONE : THE PILGRIM’S ROAD

1 A Message from Icarus

2 The Stranger on the Train

3 The Imaginary Ex

4 The Eccentric Bibliophile

5 Encounter with a Wing Three-Quarter

6 Shell Game

7 The Flight of the Blessed Antonia

8 A Sporting Chance

9 The False Prisoner

10 The Special Reserve

11 Beside The Still Waters

PART TWO: THE CITY OF LIGHT

12 A Knight Errant

13 The Last Guardians

14 The Conjurer

15 The Blighted Spirit

16 The Oracle

17 Scavenger Hunt

18 A Matter of Kings

19 The Host of Heaven

20 The Hunting Party

21 The Return of Odysseus

22 The Final Beginning

Author’s Note

PART ONE

THE PILGRIM’S ROAD

1

A MESSAGE FROM ICARUS

We were hiking through the familiar landscape of my childhood when the sound of an aeroplane changed everything. That reverberation in the distant air brought back memories very different from my boyhood in the Scottish Lowlands, before my father moved us all to South Africa. It reminded me of a time many years ago when I had fled through these hills as a fugitive from justice, chased by the police and by agents of the Black Stone, who were the real perpetrators of the murder of which I stood accused.

Now, in June of 1940, my circumstances were very different. For one thing my wife Mary was walking at my side, the bright northern sun gleaming on her fair hair, swinging her arms as carelessly as a schoolgirl on the first day of a summer holiday.

For another, I was as far from being a wanted man as it was possible to be. Several times in the past I had been flung into the most extraordinary adventures, such as when the doomed Scudder waylaid me at my front door and pitched me into a deadly cat-and-mouse game with the Black Stone. More than once during the Great War, Sir Walter Bullivant had summoned me from the front lines in France to be sent off on a perilous mission across enemy territory. But now that a fresh conflict had broken out, it appeared that no one required the services of Richard Hannay.

Upon the declaration of war with Germany, I had immediately telegraphed the War Office, asking that my commission might be reinstated so that I could play a full part in the struggle to come. When this appeal met with no reply I wrote directly to Sir Walter Bullivant’s successor at the Foreign Office, Lord Charnforth, setting forth my qualifications and experience at greater length than I felt comfortable with, as it goes against the grain to sound my own trumpet.

The dispiriting reply I received was signed by a subordinate I had never heard of and was couched in the most bland and bloodless language. In short it advised me that a large number of requests from former service personnel were currently being processed and that it would require a considerable time to give them all proper consideration, especially in view of more pressing concerns.

My attempts to contact Lord Charnforth directly by phone were rebuffed at every turn by an impenetrable wall of secretaries and minor functionaries who were bent on preventing his lordship from being disturbed by anyone other than the king or the prime minister. I was advised repeatedly to ‘bide my time’.

Bide my time! With Europe going up in flames!

What had been loosed upon the world was not, as the poet warned, mere anarchy, but a dreadful iron order that crushed all under the wheels of its relentless advance. Nations to the east and the north had fallen before its lightning aggression and now France, whose mighty army we expected to stand as a bulwark against the coming storm, had crumbled before it. Armour and manpower were flooding through her shattered defences like water through a collapsing dam.

And here was I, as useless as a sword left rusting in the scabbard.

When I could bear inaction no longer, I sought to soothe my frustrations by getting far away from the brass hats in London. Mary insisted on joining me, declaring that I was not to have all the fun while leaving her in the clutches of the local Ladies’ Literary Circle. She added that this would be an opportunity to visit friends in Scotland we had not seen in ages.

Tramping through the country where once I had played, fished in the streams, swum in the quiet pools, I hoped to find the calm I so ached for. But today, instead of being comforted, I found my thoughts turning to the very different fate of one of my oldest friends whose recent death haunted me like a melancholy ballad.

Mary’s voice broke in on my solemn reverie. ‘You’re thinking of Ned Leithen again, aren’t you?’

Though she was many years younger than I, she had always been the wiser of us two. ‘Do you always know what I’m thinking?’ I asked in surprise.

‘Not always, but when I see that pained crease form between your eyebrows, I can be pretty sure your mind is on thoughts of lost friends. I saw that look many times after the last war whenever you were remembering Peter Pienar or Launcelot Wake.’

‘I had no idea I was so transparent.’

‘Only to me, darling. Besides, it was just a few days ago you met with Lamancha, Palliser-Yeates and the others for your private memorial. It’s the sort of occasion it takes you a while to shake off.’

Indeed it had been only five days since that gathering in London where we toasted the memory of our late friend Edward Leithen. A noted lawyer and respected MP, Leithen had enjoyed his own share of adventures over the years, but the damage done to his lungs by a gas attack in the Great War had proved to be a slow killer, dogging his footsteps until his doctor gave him no more than a year to live.

Rather than spend the remaining months in comfort, Leithen determined to die on his feet and trekked off into the northern wilderness of Canada in search of a lost soul in need of rescue from more than the viciousness of the Arctic climate. That mission accomplished, Leithen had spent his final days among a brotherhood of missionary priests serving a native tribe devastated by a virulent outbreak of fever.

‘It’s true,’ I admitted. ‘I can’t help reflecting on the contrast between Ned’s final quest and my pleasant walking tour of Dumfries and Galloway.’

‘Speaking for myself,’ said Mary, ‘I’m perfectly happy not to contend with freezing blizzards and mountains of ice. Remember, Dick, he knew his time was up, whatever he did. You’re in the best of health with many good years ahead of you.’

‘Yes, but what sort of years? Am I going to carry on comfortably tending to the garden, checking the livestock, seeing to repairs around the house? There was a time I did want that, resisted any efforts to drag me away from the good life we’ve made together. But not now, not while other men are placing their lives at the ultimate hazard.’

‘You’ve done more than your share, you know that,’ said Mary. ‘But I don’t doubt that a call will come.’

‘When?’ I demanded impatiently. ‘Archie Roylance is back in uniform, game leg and all. Lamancha is a member of the War Cabinet with responsibility for munitions. Nobody seems to know where Sandy is, but I’ve no doubt he’s off on some mad jaunt aimed at bloodying Hitler’s nose. And me? By the time my call comes I’ll be too decrepit to answer it.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous, Dick,’ Mary responded with a chuckle. ‘You may have a few grey hairs, but you haven’t exactly gone to seed.’

‘Oh no? Let me tell you something. Just last week I ran into that dull fellow Welkins.’

‘What, the podgy banker?’

‘Yes. And do you know what he said to me? He suggested that I take up golf. I ask you, do I look like a man who’s so far gone that he’s ready to take up golf?’

‘No, not yet.’ Mary laughed. ‘But if you want to stave off that awful day, you can stay in shape by keeping up with me – if you’re up to it.’

She tripped off through the heather, so fleet of foot one would have thought the pack on her back weighed nothing at all. I hooked my thumbs through the straps of my own pack and followed as keenly as a man in an old folk tale chasing fairy lights through the gloaming.

For four days we had enjoyed the invigorating freshness of the air sweeping in from the Irish Sea and the unfailing hospitality of the local cottagers. Each morning we were sent off on a hearty breakfast of ham and eggs, while any daytime stops were met with buttered scones and treacle biscuits washed down with mugs of coarse India tea brewed strong enough for a mouse to walk on. And at night, of course, there was always the obligatory nip of whisky before settling into a rough bed for a welcome sleep.

It had rained heavily in the night but the morning sun had burst through the clouds to cast a bright sheen over the freshly washed landscape. Fed by the overnight rain, the streams bounced and gurgled over pebbles and rocks, as excited as children escaping from school. As the sun slanted towards the west, the cries of plovers and curlews echoed off the hills and the breeze carried a tang of burning peat from the hearth of a far-off cottage.

All at once, as if the musical piping of the birds were the introductory notes of an accompanist, Mary began to sing ‘Cherry Ripe’, just as she had when I came across her for the first time in the garden at Fosse Manor. It was then that she had identified herself as my contact with instructions from Sir Walter Bullivant. I had been gladly following her orders ever since.

Her song was cut short when we caught the noise of an engine approaching out of the eastern sky. The sound reminded me of how my enemies had once used a plane to pursue me across this very landscape. The memory quickened my pulse and I felt my heels itching to take flight. It was a ridiculous reaction, given that I was no fugitive, but a respected war hero living in comfortable retirement. And yet my instincts told me clearly that something was up.

‘Look, he’s turning this way,’ said Mary, shielding her eyes against the sun to examine the approaching plane.

I could see now that it was a two-man biplane, the two wings fixed together with an arrangement of struts and wires. It wasn’t unlike the plane Archie used to take me up in to reconnoitre the German positions before their big push of 1918. The pilot had completed his turn and was now flying directly towards us.

‘Yes,’ I agreed, ‘it’s almost as if he were looking for us.’

Mary laughed at my wary tone of voice. ‘Dick, I hardly think with all that’s happening in France, anyone would spare an aeroplane to seek out a pair of ageing hikers.’ She squinted at the approaching craft and pursed her lips. ‘It looks like a Tiger Moth. A DH.82, probably, with a de Havilland Gipsy III hundred and twenty horsepower engine.’

I knew she had been considering a position with the Observer Corps, which required the ability to accurately identify aircraft at a distance. To that end she had made an extensive study of aircraft design, both ours and those of the Germans. I also knew she had no intention of taking up such a post so long as I was forced to remain inactive, knowing that it would only exacerbate my own chafing frustration.

While I didn’t have her knowledge, my eyes were just as keen. ‘I don’t see any markings on it,’ I noted.

‘No, it’s a civilian plane,’ said Mary, ‘but the RAF are drafting them in to use as trainers.’

‘Yes, I can see it’s a two-man job,’ I said. ‘But it looks like there’s only the pilot aboard. You know, I swear he’s waving at us.’

‘Probably just being friendly,’ said Mary. ‘I don’t think I could be that casual while flying. I would keep thinking of Icarus flying too close to the sun and his wings melting.’

‘Icarus’s wings were made from wax and feathers,’ I said. ‘I’m sure that crate is fashioned out of something more durable.’

Even as I spoke, there came a dull boom, and a gust of smoke blossomed from the rear of the approaching plane. Immediately it began to sway and buck. As it roared directly over us we could see the pilot struggling desperately with the controls.

He plunged so low over the nearest hill that he panicked the sheep grazing there and put them to flight. As the plane disappeared over the hill, we raced up the slope as fast as our legs would carry us with our packs bumping against our backs. We were mounting the crest when we heard the sickening crump of the aircraft striking the ground.

We scrambled down the other side towards the wreck, fragments of loose scree flying up from our heels as we descended. The wheel struts were crushed, the fuselage was cracked in two, and the pilot lay slumped over the controls. As we drew closer I could see sparks sputtering from the electrics and smell the dangerous stink of petroleum in the air.

‘Stay back!’ I warned Mary.

She ignored my advice and followed me at a run to the plane. When we reached the pilot I undid his safety harness and the two of us hauled him out of the cockpit. Supporting him between us, we hurried to a safe distance. As soon as we laid him out on the ground, there came a stomach-wrenching blast as the fuel tank exploded, setting the ruined craft ablaze.

I snapped loose the strap of his leather flying helmet, pulling it off along with his goggles. The face that stared blearily up at me was youthful, and from its pallor and the blood oozing from his mouth, I could tell he had suffered terrible internal injuries from the impact of the crash.

As Mary yanked open his heavy flying jacket to ease his respiration, he gazed at me with a glint of recognition in his eyes.

‘General Hannay!’ he croaked.

Somehow my intuition had been correct. He was looking for me.

‘Rest easy,’ I cautioned him. ‘We’ll find a doctor and get you to a hospital.’

He shook his head and took a feeble grip on my arm. Face contorted in agony, he forced out a hoarse jumble of words: ‘London trails . . . latest Dickens . . . missing page . . .’

I felt his fingers slip from my arm, as if he had summoned the last of his strength to deliver this incomprehensible message.

‘Please don’t strain yourself,’ Mary pleaded, gently brushing the sweat-stained hair from his brow.

I could hear in her voice that she was as aware as I that the young man was a goner. However, as a spasm of pain shook his body, he made a further effort at speech. If his words so far had been enigmatic, his final exhortation was utterly baffling.

‘Thirty-one kings,’ he whispered with his dying breath. ‘Find the thirty-one kings!’

2

THE STRANGER ON THE TRAIN

I felt for the pilot’s pulse as his eyes fixed sightlessly on the sky from which he had fallen. Turning to Mary, I sadly shook my head. She gazed down pityingly at the young man.

‘Dick, what on earth was he talking about? I can’t make head nor tail of it.’

‘Given the condition he was in, he might just have been raving,’ I said dubiously. ‘And yet he obviously knew who I was.’

‘You were right all along,’ she agreed. ‘He was looking for you. So that must be some sort of message, however garbled.’

I closed the young pilot’s eyes and we straightened up. I saw Mary’s gaze drift towards the burning wreckage of the crashed Tiger Moth and the plume of acrid smoke that floated above it. Her eyes narrowed and her mouth took on an atypically grim cast. I knew at once that she was thinking of our son Peter John who was now a pilot in the RAF flying sorties across the Channel.

It seemed only fitting that he – who so loved birds of prey that he had raised and trained several of them – should have become one himself. The terrible difference was that the quarry he hunted had talons of its own with which to strike back.

I knew that if Mary did take a post with the Observer Corps she would not simply be scanning the skies for enemy aircraft. She would, whether consciously or not, be keeping watch for the safe return of her son.

With an effort she tore her eyes away from the scene. ‘Do you think this was just an accident?’

‘It’s too much of a coincidence to swallow,’ I said. ‘I’d bet a pretty penny the plane was sabotaged.’

Before we could speculate further a voice hailed us from a hilltop to the north. A shepherd in a tartan bonnet was shaking his crook at us to get our attention. I waved back and he loped down the hillside towards us with a pair of excited collies scampering after him.

When he reached us he paused to catch his breath and stared down grimly at the pilot. ‘When I saw yon plane drappin’ oot o’ the sky, I kent well there was little hope for the man that flew it. There’s enough o’ they laddies lost o’er in France wi’oot this.’ He removed his bonnet as a mark of respect and stroked his shaggy beard at the tragedy of it. ‘It’s doonricht lamentable.’

‘We’re strangers around here,’ I told him. ‘Can you contact the local authorities to come and take care of him?’

‘Aye, Dougal Mackie’s place is no far off,’ said the shepherd. ‘He’s had a phone put in, swell that he is. I could fetch the polis on that.’

I indicated to Mary that we should be on our way and we started off at a brisk pace.

‘Where are ye off tae?’ the shepherd called after us. ‘The polis might ask efter ye.’

‘We’re going to London,’ I told him, ‘to find some kings.’

By nightfall we managed to reach a small rural station. Flower baskets hung over the platform and a Union Jack fluttered beside the tracks. There were fewer services running because of the wartime demand for coal, so we spent an uncomfortable night in the station waiting room until the morning milk train came chugging along. There were scarcely any passengers, so we easily obtained a carriage to ourselves where we stowed our packs in the overhead rack. The accommodation was luxurious compared to the wooden benches of the waiting room and we looked forward to catching a few extra winks of sleep on the journey to Dumfries.

‘I shall have to phone Barbara and let her know we won’t be coming after all.’ Mary sighed as she gazed out at the wooded glens and gleaming lochs.

‘We’ll do it another time,’ I said. ‘Perhaps by then Sandy will be home and we can have a proper reunion.’

‘Yes, let’s hope so,’ said Mary, stifling a yawn. She rested her head against the window and closed her eyes.

I had promised Mary that after our tour of Galloway we would pay a visit to Laverlaw, Sandy Clanroyden’s estate in Ettrick, to spend a week there with his wife Barbara and their young daughter Diana. I was less enthusiastic than my wife, not from any lack of enjoyment of Barbara’s company or delight in the beauty of the place, but I knew that I would feel Sandy’s absence keenly. Knowing he was out somewhere in the world, playing his part in this conflict, made it doubly galling that I was not doing the same.

Sandy and I had served together in France and much further afield. During the Greenmantle affair he had infiltrated the organisation of the beautiful and brilliant German agent Hilda von Einem. She had been grooming a Mohammedan visionary to be the leader of a great uprising that would shift the balance of power in the East in favour of the Kaiser. When her pawn died of cancer, she was so taken in by Sandy’s assumed disguise as an Oriental mystic, that she chose him as a replacement. His betrayal of her incensed the woman – but it hurt him too.

When things came to a head, our little band were holding a ruined hill fort at the battle of Erzerum in Turkey. Hilda von Einem approached us under a flag of truce, offering us not only our lives, should we surrender, but renewing her offer to Sandy to stand at her side and become the ruler of a great empire.

The temptation came not from any desire for power on Sandy’s part, but from the strange, almost hypnotic attraction she held for him. To say he had fallen in love with her was to put it too mildly, but still he refused, then watched in horror as, while heading back to her own troops, she was killed by a shell from the attacking Russian artillery.

We buried her with honour, but I know her death haunted Sandy for years, right up to the time that he met Barbara during his visit to South America. I had a worrying suspicion that even now he was constantly subjecting himself to the most terrible risks out of a sense of guilt: that he had betrayed that fascinating woman and helplessly watched her die.

As I mused upon the many other scrapes Sandy and I had been through together, the train made a stop and a dozen assorted passengers boarded, some with dogs and one accompanied by a pig. The corridor door to our compartment slid open and in shuffled a tall man dressed in a heavy overcoat. A thick woollen scarf was wrapped around his mouth while the rest of his face was overshadowed by a wide-brimmed fedora.

‘Sorry to disturb,’ he apologised, his voice muffled by the scarf. ‘Got a bit of a chill. Need a quiet spot to shut my eyes. Other compartments full of noise.’

Mary stirred from her slumber and gave him a friendly smile. ‘Do sit down,’ she invited him. ‘We’ll do our best not to disturb you.’

‘Obliged,’ the stranger grunted.

He slumped into the seat opposite us in the spot nearest the door. His eyes closed, his head slouched forward, and his breath sounded slow and steady beneath the covering of his scarf.

We both knew without a word being said to confine our conversation to trivialities. Mary talked some nonsense about fashion while I pretended to be thinking of buying a new bicycle, both of us sotto voce.

Our silent companion did not stir, not even when we halted at a tiny station for a minor exchange of passengers. A florid countryman in grubby tweeds and a woman with two squabbling children passed in the corridor but were not inclined to join us, perhaps because the fellow in the coat gave every appearance of ill health.

As we pulled out of the station Mary gave a sigh. ‘Do you suppose there’s a dining car? I’m feeling rather peckish.’

‘I’m sure they’ll have coffee available at least,’ I assured her.

‘In that case I’ll go foraging,’ she said, standing up and straightening her skirt. ‘I’ll only be a few minutes.’

The moment she left the compartment the stranger raised his head and his eyes flickered open. He pulled the scarf away from his mouth and tipped back the brim of his hat to reveal a lean face with a large nose and sharp cheekbones. His moustache had turned completely grey, lending a certain affability to his intelligent features.

‘It’s a relief to be free of that scarf. I was feeling quite stifled.’

I recognised him at once and was not pleased to do so. ‘Joseph Bannatyne Barralty.’

He doffed his hat in acknowledgement. ‘Sir Richard Hannay. Delighted to meet you again.’

I knew Barralty from a previous encounter some years before. He was what many people would describe as a professional rogue, but in spite of his shady dealings he had never yet fallen into the clutches of the law.

‘I’m pleased to see you’re not as poorly as you first indicated,’ I told him. ‘In fact, you look quite well.’

‘Speedy recoveries are a speciality of mine. And you, Hannay – a few days in the wilds certainly seem to have put some colour into your cheeks.’

‘It’s very good of you to say so.’

He removed his hat and set it down on the seat beside him.

‘Well, now that the pleasantries are out of the way,’ he said, smoothing back his hair, ‘we can get down to business.’

‘I’m afraid I’ve no business to offer you,’ I said. ‘I’m on holiday, in case you didn’t know.’

‘I’m sure you’re familiar with Milton’s dictum, “They also serve who only stand and wait”. Unless I am much mistaken, your waiting time is over.’

I felt a prickling at the back of my neck, such as often warned me of approaching danger. ‘You are much mistaken,’ I told him evenly. ‘I’ve been a civilian for many years now and intend to continue in that avenue. I would advise you to do the same or one day you will be tripped up by your own supposed cleverness.’

He tutted and shook his head. ‘Would that things were as you say, but in a time of crisis such as we are living through now, there will be precious little peace for either one of us. There are too many pressures, too many opportunities, and in your case the call of duty.’

Barralty spoke pleasantly but I was not deceived.

‘You know, I really preferred your company when you were still asleep,’ I said pointedly. ‘You’re proving to be rather tiresome.’

He leaned forward and fixed his shrewd eyes upon me. ‘There is no reason for any antagonism between us. You will recall, Mr Hannay, that although we were on opposite sides during that Halverson affair, we nevertheless parted on reasonable terms.’

My hackles rose. ‘If you’ve turned Nazi, Barralty, I don’t think we’ll be parting quite so amicably this time.’

‘I’m no Nazi,’ Barralty scoffed. ‘You surely can’t think that.’

‘No,’ I conceded, ‘but I do know you always have an eye for the main chance, and I suppose their money is as good as anybody’s, provided there’s enough of it to quiet your conscience.’

Barralty looked pained. ‘I assure you, Hannay, that my . . . associates in this matter are patriots of the highest standing.’

‘Patriots who don’t mind killing their own,’ I reminded him with some bitterness.

‘That chap in the plane?’ Barralty cocked a dismissive eyebrow. ‘As soon as he realised something was up with the engine, he should have put down or bailed out. Instead he pressed on with his search for you, even to his own destruction. Which suggests to me that he had a message of some import to pass on.’

‘It would have been better if you asked him about that yourself. Unfortunately that’s no longer an option.’

Barralty spoke in a measured voice, but there was a threat underlying it. ‘I’d be very much obliged if you would share that message with me.’

‘If you’re looking for a letter,’ I said, spreading my hands, ‘I swear I haven’t got one.’

‘It wouldn’t be written down,’ he countered. ‘I’m sure it was passed on by word of mouth.’

‘You’re out of luck there,’ I told him coolly. ‘He didn’t survive the crash. And dead men have very little to say for themselves.’

‘If you received no word, no call to arms, then what possessed you to abandon your pleasant holiday and head south in such haste?’

‘I’m tired of eating burnt ham and greasy eggs for breakfast,’ I said. ‘I got a sudden yearning for kippers and French toast.’

The side of his mouth twisted unpleasantly. ‘I’m afraid flippancy really won’t serve, Hannay. You know I have the deepest respect for you, but I am in the employ of men who expect results, not witticisms.’

As he said this, his right hand slipped into the pocket of his coat. I had no doubt as to what was concealed there.

‘Would you really go so far?’ I queried.

Barralty’s eyes narrowed. ‘Mr Hannay, it is not to my taste to have your lovely wife return to a scene of violence, but you really mustn’t press me. Now tell me what message that unfortunate man brought you.’

I saw the muscles tense in his neck and knew his finger was tight against the trigger.

‘I wish I could oblige you, old man,’ I responded with mock affability, ‘but I really have no idea what you’re talking about.’

‘In that case I will have to insist that both you and Mrs Hannay get off at the next stop with me. Some friends of mine are waiting there with a car to take us to an isolated location where you can enjoy a period of quiet seclusion.’

‘I’m sure the peace and quiet would be restful, but I couldn’t put you to all that trouble. Besides, my wife has her heart set on lunch at Claridge’s tomorrow.’

‘I am doing my best to be civilised,’ said Barralty through gritted teeth, ‘but you are making it impossible. My instructions are clear. You are to leave the train with me, or you will not leave it at all. Neither one of you.’

It was at that moment that the corridor door slid open and Mary entered.

3

THE IMAGINARY EX

Sliding the door shut behind her, she flashed a casual smile at Barralty. ‘Oh, I see you’re awake,’ she observed pleasantly. ‘So glad you’re feeling better, Mr . . . I’m sorry, I didn’t catch your name.’