7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Old Street Publishing

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

A family of Hasidic Jews dies suddenly while picnicking in Finsbury Park, and the finger is quickly pointed at a gang of Islamist youths. Too quickly, thinks local reporter Rex Tracey. Rex starts to investigate. But when his long-time colleague and friend is also accused of murder, the sleuthing journalist with a fondness for Polish lager and dry one-liners is catapulted out of his depth, into a disturbing world of religious fanaticism, false prophets and century-old secrets.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

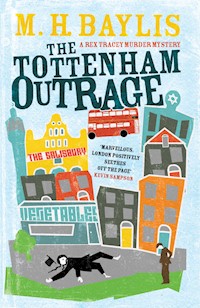

THE TOTTENHAM OUTRAGE

M. H. Baylis

To my beautiful wife, Emma

Contents

Chapter One

Terror, Rex knew, could strike at any moment. Not just any moment, in fact, but at the very moment of highest road-confidence and car-handling aplomb. He could blithely conquer the dozen tangled exits of the Great Cambridge roundabout, or the roaring spaces of the flyover – and then, suddenly, while trying to shift from 4th to 5th gear, glimpse one of those makeshift, flower-and-photograph shrines tied by the grieving to the grey metal barriers at the sides of the road, and think: No. I cannot be here. Doing this.

Sometimes there wasn’t even a trigger. He might just be idling in the traffic down Green Lanes, behind some van dropping off wads of pide bread and buckets of olives at one of the borough’s three hundred Turkish restaurants, when a snapshot of himself at the wheel would suddenly rise before his mind’s eye, and amidst the cold sweat and the thudding heart, it would be as if he’d never learnt to drive. Now, or before, in the old life.

If you were acquainted with the bulky, suited man at the wheel of the rust-coloured car passing slowly down the Lanes, you might understand a little of his dilemma. You would know that there was more to the predicament of this man of 41, about to take a belated driving test, than met the eye. If you didn’t know Rex Tracey, on the other hand, you might see only a faintly familiar-looking man, rather gaunt in the face, a little tubby round the middle, with a hangover and an understandable longing on this bright, blustery March Monday to be anywhere other than in a traffic jam crawling through the heart of Haringey.

Traffic jams were the worst. The longer he was still, the more time he had to ponder what the hell he was doing, and the greater the chance of that simultaneously cold and hot flush passing up and down his body, leaving in its wake the desire to crack open the door and flee. Out of the car, out of the borough. Perhaps out of the country.

The van in front moved forward. Rex started up – and stalled. Horns sounded behind him. He swore. Terry placed a calming, priestly hand on the dashboard.

‘Fuck ’em. Take your time. Everyone stalls. They won’t mark you down for it.’

He couldn’t run, of course, he knew that. He’d been caught in one of fate’s pincer movements, a little man swept up in big events. Like the simultaneous expansion and contraction of the borough he lived in, worked in and worshipped. There seemed to be more people arriving, certainly there were more flats being built. Yet more and more of the old bakers and grocers on the Lanes were closing down, with new signs appearing in their place, making dangerous promises like Cash4Gold and PayB4PayDay.

Meanwhile the local newspaper for which Rex worked, the Wood Green Gazette, had uneasily morphed into an online news site called News North London, whose territory expanded every day, while its dwindling staff were required to put in six days’ work for four days’ money.

A further development was that Rex’s boss, a formidable yet elegant New Yorker named Susan Auerglass, had strongly intimated that his extended news beat could no longer be covered on buses. He’d been able to ignore her until the photographer, his colleague Terry, had started moonlighting as a driving instructor to cope with the new mortgage he’d taken out shortly before the pay cuts.

Hence: Rex, a man with every reason never to get behind the wheel of a car again, behind the wheel of a car again. New laws said he had to re-take his test if he hadn’t driven for a decade, which was exactly how long he hadn’t driven for. So here he was, with Terry, in Terry’s 1982 Vauxhall Chevette, taking one final lesson before tomorrow’s test. They often combined these lessons with assignments, and today reporter and photographer were heading south to Finsbury Park to interview a local author.

The ancient thoroughfare they were on stitched a path from the high plains of Hertfordshire down to the stews of Islington, taking in a dozen ethnic enclaves in between. Green Lanes ought to have been, perhaps was, a symbol of the new, fast-moving, global society. But nothing, neither goods nor people, ever moved along it without a great struggle.

‘I swear they were digging the hole on the other side when I went by here first thing,’ Terry grumbled, as a bottleneck around some sewer-related digging finally eased.

‘What were you doing down here first thing?’

‘What’s this bloke written, anyhow?’ Terry asked, ignoring Rex’s query, as they passed under the railway bridge, with its greetings in seven languages. ‘Book about Finsbury Park is it?’

‘Something about the Outrage,’ Rex said tightly. He wasn’t comfortable talking while he was driving. ‘He insisted on meeting in the caff in the park.’

It was true. The man had insisted to the point of rudeness, in fact, seemingly unaware how lucky he was to get a free mention in the media for his self-published local history book. Rex was not looking forward to the interview.

After turning right onto Endymion Road, he reversed towards what had looked at first a very generous gap, but which seemed to have shrunk radically now that he was attempting to park in it. It didn’t help that the car behind contained a trim, elderly, bearded man, sitting in the driving seat and passing judgement on Rex’s parking skills with an assortment of rolling-eye and shaking-head gestures. Terry countered with a soft mantra of encouragement, but his pupil’s nerves grew increasingly frayed as he rued not just his failure to park today, but the inevitable failures of the morrow, which would take place under the gaze of an examiner, wielding a clipboard. With a sickening crunch Rex reversed into the bumper of the bearded man’s car. The man shot out of his vehicle as if he’d been jabbed with a spear.

‘I’ll sort it,’ Terry said, unbuckling his seat belt and reaching across to the wheel. ‘You get out and calm the old git down.’

The ‘old git’ was in his mid sixties, neatly turned out in a navy blazer and pressed grey trousers. It was an unfamiliar look in these parts.

‘Insurance details,’ he snapped. He held out a hand, and when Rex didn’t immediately put paperwork into it, he clicked his fingers.

‘Perhaps we’d better assess the damage first?’ Rex said.

Nothing had occurred to the man’s front bumper other than a slight scuff, but after some time spent on one bended, knife-creased polyester knee, scratching and sniffing and apparently tasting the damage site, the man felt otherwise. He stood up.

‘I’m assuming you do have insurance?’ he rasped charmlessly.

‘My friend has full cover,’ Rex said, gesturing toward Terry, seated in the now perfectly parked car. ‘He’s teaching me to drive.’

The man snorted, and was clearly about to offer some sardonic comment when the tough, wiry frame of Terry emerged from the car, and stopped him in his tracks. He froze. ‘You,’ he said quietly.

‘Aye,’ replied Terry, inclining his long, buzz-cut Viking skull. ‘Me.’

‘You two know each other?’ Rex asked.

‘This is the bloke who lives next door,’ Terry said bitterly.

Rex, and everyone in the office of News North London, had heard a great deal about the bloke who lived next door to Terry. About the dispute over the bins, and over the slamming of the shared front door, and how the tempers of both men had flared up within a day of Terry moving into the property eight months ago, and not receded since. They also knew about the man’s typewriter, and his habit of operating it, loudly, in the room adjoining Terry’s bedroom, between midnight and six am, and about the man’s habit of communicating his dissatisfaction with his neighbour’s transgressions via a stream of neatly-written Post-it notes.

After scrimping for years, and then dangerously over-extending himself to purchase a little Edwardian half-house in a street behind Turnpike Lane tube station, Terry had, as the editor Susan put it, landed himself a turkey.

‘Well since you’re here, I might as well tell you I’m not happy with the colour of that section of glass you replaced in the front door.’

Rex saw the Geordie’s fingers curl and uncurl, his bony chest rise and fall. He was displaying remarkable self-control, Rex thought.

‘Actually, could we just swap insurance details and talk about the other business later?’ Terry said. ‘I’m supposed to be photographing some local writer bloke in the caff, and I’m late.’

The man gave a thin smile. ‘If you went to “the caff” now you’d find your “local writer bloke” wasn’t there either. Because he’s standing on Endymion Road talking to the clowns who just crashed into his car!’

It was not a great start, and the three men made their way in silence to the park. There had been a time when the mere mention of Finsbury Park conjured visions of discarded needles and gang rapes. Yet, thanks to an injection of Lottery money and the council’s somewhat Blitzkrieg-like approach, that was all in the past. They’d put in lighting, bulldozed the reeking catacombs of sin that had once passed for lavatories, dredged the Boating Pond (finding, in the process, a human finger), and tamed the hedges.

Today, a bright morning after a long, stone-grey winter, the area around the café was buzzing with kids and parents enjoying themselves with the vigour of the newly-freed. Even though the air was cool, and the park had a chewed-up look after the ice-melt, it felt pleasantly warm in the new, octagon-shaped café, sitting in the sun that came through the huge windows. The man – a retired history lecturer named Dr George Kovacs – was about to publish a book about the Tottenham Outrage, an infamous, politically motivated wages-snatch that had taken place in the area back in 1909. The book wasn’t actually out yet, due to what Dr Kovacs called ‘stupid and inexcusable mistakes by the printers’. This meant that Rex hadn’t been able to read any of it, which, irrationally, made Dr Kovacs even more irritated.

‘So what new light is your book going to shed on the story, Dr Kovacs?’ Rex asked, doggedly sticking to the questions he’d prepared.

Kovacs had large, sad, spaniel eyes with prominent bags beneath them. He rolled them fractiously. ‘I’m not going to provide you with a synopsis of my book,’ he replied, in a prickly, precise manner that reminded Rex of Prussian officers in war films. His accent had a trace of Merseyside in it. ‘If you or your readers wish to know what’s in it, then you and they will shortly be able to purchase a copy from one of the three outlets I have already mentioned but will now mention again: the Big Green Bookshop, Muswell Hill Books or the Bruce Castle Museum Shop.’

Rex started to speak but Kovacs interrupted him.

‘Suffice it to say, Mr Tracey, I have interesting new information, which throws light on the Anarchist terror group to which the robbers were connected. And on what happened to the money they stole from Schnurrman’s Rubber Factory.’

‘I thought both of the robbers were killed as they tried to escape,’ Rex said, glancing up at Terry as he made his way back from the toilet.

‘A comment which merely demonstrates your ignorance of the subject. One, Josef Lapidus, shot and killed himself at the end of the chase. Another, Paul Helfeld, was shot by the pursuing police and died two weeks later from his injuries. Neither was found in possession of the money stolen from the rubber works.’

‘And you think you know what became of it?’

‘Historians assess evidence and draw conclusions.’

‘I see. So what evidence makes you conclude that people might be interested in a robbery that happened here in 1909?’

‘It was the first hint of the Tottenham we live in now. Global, multicultural, connected. Latvian anarchists committing crimes in London to fund acts of terror in Russia. Robbing a factory so dependent on a casual, ever-shifting immigrant workforce that the bosses weren’t even aware Helfeld and Lapidus had been on the payroll under false names. A rubber factory, I should add, that processed latex from our colonies in Singapore and India into bicycle-tyres for use on the cobbles of Tottenham.’ Kovacs paused. ‘I have no idea whether that interests “people”, Mr Tracey. I imagine most “people” would rather read a footballer’s biography. My book is not written for them. It is written for the sake of history.’

‘Good luck with the sales,’ Rex replied, brightly.

The bickering might have continued but for a sudden outbreak of shouting from the playground outside. They looked round. A tall, bearded youth in a combat jacket stood over a family of Hasidim picnicking at one of the wooden tables by the climbing frame. The youth said something, roughly, but not as aggressively as his first outburst, then laughed. Lobbing something into the bushes, he walked over to join his mates: a clutch of Asian lads dressed in a combination of long, Islamic-looking shirts and sportswear.

‘I just seen that lot out on the boating lake, giving it all this,’ Terry commented as he reached the table, snapping his thumb and fingers together to imitate a yapping mouth. ‘They don’t listen, do they – dressing up like that?’

‘Can we get on?’ Dr Kovacs groused. ‘I had an unexpectedly long walk this morning, followed by a traffic accident at your hands. I’d quite like to get home as soon as I can.’

Rex suggested they go outside to take some photographs. It was getting warmer, and they positioned themselves under a sycamore tree next to the main playground. Kovacs glowered into the lens as Terry snapped away and Rex took the opportunity to study the boys who’d allegedly been making trouble on the boating lake. They’d now gone into the café, where they’d swiftly become mired in some sort of dispute with the Polish girls behind the counter.

It was a classic Haringey tableau, he thought: kids at play, a United Nations force of knackered mums, gnarled old men with worry beads – and a small number of under-occupied young men spoiling it for everyone else.

He looked back at Dr Kovacs, squinting into Terry’s lens. The man was an anomaly. The blazer and the trousers had a grim sheen on them; old but not great when they’d been new, either. On his feet, though, was a pair of soft, dove-grey boots that might well have been made for him. His watch was an old-looking Rolex – again something quietly announcing wealth. A man who cared about the details, perhaps, but not about the bigger picture. Did that make a good historian?

Suddenly a scream pierced the scene, then seemed to drain it of life. It wasn’t the usual playground shriek, from a child going too high on the swings or being dragged reluctantly home. This was an adult scream. A woman’s scream.

Everyone stared towards the farthest of the wooden picnic tables. A slim blonde woman – her fashionable sheepskin boots and her high ponytail announcing which side of the park she lived on – held an identical-looking little girl by the hand. The girl gazed tearfully up at her mother, who in turn stared down at the table, muttering something over and over to herself.

Slumped inertly around the picnic table was a family: a mother, a father, a girl, a boy and an infant. Their heads rested on the slatted wooden surface, among assorted tupperware and bowls and cups. They might have all suddenly fallen asleep. But they were not asleep. The groups of people who fearfully approached the table knew it, as did all the people who had remained rooted to the spot with sudden dread. With a gust of spring wind, a black felt skullcap rolled from the table onto the sandy soil, picking up a shred of damp, pink blossom on the way. A child’s chubby arm dangled loosely in space.

‘They look like them freaky ones up in Gateshead,’ Terry whispered. ‘Orthodox.’

‘Not Orthodox,’ Dr Kovacs said quietly. ‘Hasidim. Hasidic Jews. From the Dukovchiner sect.’

‘How can you tell?’ Rex asked, staring in horror at the way the older boy’s blond ear-curls had spread out like seaweed across the table.

‘The woman. Most Hasidic women wear wigs. But not Dukovchiner. They keep their own hair.’ Kovacs’ voice appeared to choke up. Rex glanced up and was surprised to see how pale the man had gone. Their eyes met.

‘I have to go now. I’m sorry,’ Kovacs said suddenly. He hurried off towards the main gates, turning just once to look back at the picnic tables.

‘Has anyone called the police?’ Rex asked, realising as he spoke that a dozen people, including Terry, were doing exactly that. Meanwhile, the blonde mother who’d discovered the bodies was pointing a finger at the Muslim boys who’d emerged from the café. She began to advance on them threateningly, her little girl, for the moment, forgotten.

‘What did you do to them?’ she shouted, patches of red forming on her cheeks. ‘I saw you. I saw you spray something at them!’

Immediately, without answering, the boys scattered, two charging through the sandpit with their shirt-tails flying, one running out of sight behind the café building, and the big army-jacketed one – the one Rex had down as a sort of ringleader – bowling right past him along the path. Sirens began to wail in the distance. A child sobbed and an old, ship-sized Turkish granny recited ‘Horrible thing, horrible thing’, like an elegy.

* * *

I pray with them sometimes. I don’t know what E and T would say to that. I like that they don’t know – something of mine after all those years we three spent shivering together, knowing each fart and scratch and dawn-rising cock and nightmare of our fellows.

On their Sabbath, Widow Cutter and her daughter pray in their house. Remind me of Old Believers a little. Some I once hauled timber with in Yakutsk called themselves ‘priestless ones’. Widow and daughter won’t have any truck with the smooth, fat-faced, frock-wearing extortionists, either, and I admire them for that. Admire the way they kneel, on the hard boards, in front of the bare wall. Don’t even have a cross. So I kneel with them, a little way behind, out of respect. Don’t really pray, of course. Haven’t prayed since I was a boy, with Grandfather beside me. Stopped saying prayers when a soldier on a horse ran the old man through like a shashlik.

No, what I do is just look at the daughter. Leah. The soft, coppery hair on her long, slender neck. The grubby undervest and petticoat I can glimpse through the holes in her Sunday frock. It has been so long. So cold. And there is no warm like that warm.

Then I grow hard, and it feels wrong, in this bare, quiet, freezing room, with these solemn women and their made-up God. So I recite my own prayer. I remind myself who I am.

I am George Smith, a gas fitter. I was born in Goff’s Oak, county of Hertfordshire, year of Our Lord 1869, joined Her Majesty’s Navy at 14, sailing under the Union flag, and a few more besides, for 25 years. Now I reside at 11 Scotland Green, lodge with a Mrs Vashti Cutter and her unwed daughter Leah. I have a wife and six children, back in Goff’s Oak, send them a four-shilling postal order every Saturday evening. Here are the dockets to prove it.

No, I’m not a hero. I’m just an ordinary subject of the King, doing what comes naturally when he witnesses an outrage on the streets of this fine borough. Honest. Ordinary. Upright. Upright as I can be with a spine like a corkscrew.

* * *

Rex and Terry had been the first media representatives on the scene, but by the time they’d made it back up Green Lanes to the offices of News North London, Sky and the BBC already had an army of tanned and blow-dried anchor-folk doing live broadcasts all over the borough. Sky had gone for the panic-inducing ticker-tape legend, ‘Jewish Family In Suspected Muslim Poison Plot’, while ‘Terror In London Park’, was the more restrained message at the bottom of the BBC screen.

Susan had both channels on in the office, and was flitting back and forth from her own inner sanctum to Rex and Terry’s desks as they updated copy and uploaded fresh images to the website. They were busy and focussed, yet a faint sense of futility hung over the whole enterprise. They’d stayed at the scene as long as they were allowed, taking pictures, interviewing bystanders, waiting to give their own statements to the police. There was no doubt they had the best insight into what had gone on at the park. What difference did that make, though, when everyone would just click the little icons on their phones and their tablets, and get live footage from the big players? News North London’s budget didn’t stretch to an ‘app’. Even if it did, the chances were that few would download it.

Yet everyone in the room cared. From the Whittaker Twins in their little ad sales corner, to the vast, unshakeable Brenda on Reception, everyone cared about their jobs, about the end product, and most of all about the sprawling, teeming, unloved area they lived and worked in. It was just that no one was sure anymore, in this new, pixelated screen-filtered world, whether caring was enough.

At the bottom of the TV screens, to occupy viewers during the inevitable dead time and pointless waffle of rolling news broadcasts, there were texts, tweets and emails from the general public. On her way past, Susan stopped and peered at them, emitting a slight grunt of approval.

‘Outrage,’ she said, tapping the screen with her pen. ‘This guy uses the word outrage. We should get that in. New Outrage At Tottenham.’

‘People will think it’s about Spurs sacking their manager,’ Terry said.

‘Plus Finsbury Park isn’t Tottenham,’ Rex added. ‘And you know what’ll happen if we get the parish boundaries mixed up.’

Just about the only thing that could really goad the local populace into tweeting, texting, emailing or phoning in its views was a geographical error. Confuse Wood Green and Tottenham, Crouch End and Hornsey – mistake any ancient parish for the one immediately to the north or south of it – and you’d be on the end of a public onslaught. Melting pot this borough surely was, but it had its own peculiar code: you might be stateless, or hail from a global region continually changing hands and borders, but once you got to Haringey, you made damn sure you knew which part was which. Maybe that was why the gangbanger kids kept stabbing each other over postcodes.

On the TV screen, the BBC reporter, a Tamil woman, stood outside the recently-opened mosque on Brownswood Road, where, earlier that morning, the boys had, it was alleged, attended a talk by an inflammatory preacher. As she spoke to the camera helicopters hovered overhead, stoking up the pulse rate. It wasn’t hard to imagine the scene unfolding inside the building behind her, as well as in the cafés and the halal butchers of the surrounding area. It would involve jackboots and Tasers, and a distinct lack of niceties. And quite possibly it would turn more young men into the sort of young men who were being hunted.

The reporter repeated the descriptions of the missing men, then cut to an interview with the man who hired out the boats on the boating lake. Irish-looking, with a boozer’s nose, he seemed depressingly proud to have played a part in the whole affair, or at least to be on the telly talking about it. The Asian boys had hired out a rowing boat from him, he said, the same boat the as-yet-unnamed Jewish family had been on shortly before. The boys had rowed theirs over to a little island in the middle, where people weren’t supposed to go because it was for nesting ducks and geese, and he’d shouted at them. They’d obeyed him and rowed away, returning the boat earlier than necessary. He’d seen them walk over to the table where the Jewish family was eating, but that was all he’d seen. He’d had to go and answer his phone.

Brenda approached Rex with a cup of tea. She placed it at the very edge of his desk, and remained standing at a distance, observing him fixedly.

‘You look very pale,’ she announced.

Brenda, receptionist, sub-editor, mother of five and matriarch to the entire News North London staff, often accused Rex of looking pale. Or feverish, or thin, or bloated, or needing to have his bad foot looked at by another, better doctor. Today, though, her concern was tinged with something else. Something manifested by the way she avoided coming too close to his desk.

‘Brenda, I am not radioactive,’ Rex said, reaching across the desk for his mug.

She wasn’t the only one to have had the idea. At the teeming crime scene, while technicians in chemical attack suits moved with balletic precision, and a unit of soldiers tented the centre of the park under yards of opaque plastic, Rex and Terry had been measured with a Geiger counter. Later, in a Portakabin that had suddenly appeared on the athletics track, a chatty, snub-nosed young doctor had taken blood, saliva and skin swabs. No one knew what, if anything, had been sprayed at the picnicking family, or even whether it was related to their deaths. No one, understandably, was taking any chances. A laminated card now in Rex’s pocket told him what to do if he suddenly experienced any palpitations, blackouts or shooting pains. The trouble was, Rex experienced most of those symptoms in the course of an average morning.

‘It’s great copy guys, thank you,’ said Susan, elegantly sipping green tea from a silver flask-top as she came out from her lair. She was attired in layers of light-coloured shirts and waistcoats and scarves, giving her the look of a priestess. ‘So where now?’

‘The mosques, get some local reactions?’

The boss shook her head, a dark ringlet coming loose from the central bun, and pointing to one of the screens on the wall. At that very moment, the fat bloke from Sky News was standing outside a different mosque, the larger and far longer-established one at Finsbury Park, talking to a group of silver-bearded elders in astrakhan hats and waistcoats.

‘Everyone’s doing that. Get over to Stamford Hill. Find out what they’re saying there. Community in shock, that kind of jazz.’

‘We don’t know they came from Stamford Hill,’ Terry said.

‘A Hasidic family, in Finsbury Park. Where do you think they came from, Terry? Chelsea? They’ll be Lubavitch or Satmar,’ she went on, mentioning the two main groups of Hasidic Jews in the area. ‘And they’ll have come straight down Seven Sisters Road.’

‘Aye, in a clapped-out Volvo,’ Terry added, with a hollow chuckle. Nobody laughed back.

‘They weren’t,’ Rex said, suddenly remembering what Dr Kovacs had said, just before hurrying away from the scene. ‘They belonged to a different group. Dukavitch or…’

‘Dukovchiner?’

‘Yes,’ he said, surprised, turning towards Brenda. ‘How did you know?’

‘Because that silly child Ellie couldn’t spell the word,’ Brenda said. ‘And I spent a month correcting it every time she wrote it. Rex won’t remember,’ she added, to Susan. ‘He was off in Thailand with that doctor girl.’

Last year Rex had taken a four-month sabbatical, after being stabbed. He’d spent much of it in Cambodia, in fruitless pursuit of a woman, and in his absence the Dukovchiner sect had apparently made the headlines. Susan leaned over Rex’s keyboard, calling up the relevant issues from the archive for him to see.

‘Micah Walther,’ she read out loud, as an image of a gap-toothed, ringleted teenage boy filled the screen. The paper was dated September 2013. ‘Fourteen years old. His family were Dukovchiner.’

‘All the same, aren’t they?’ Terry said. ‘Black hats and beards and Volvos.’

‘They have different groups, though,’ Rex said. ‘They all started in different towns in Eastern Europe and… I don’t know, some of them like Israel and some of them hate it. That sort of thing.’ He looked towards Susan for confirmation, but she merely shrugged.

‘Kids again,’ Brenda said sorrowfully to herself as she looked at Rex’s screen. ‘Always kids.’

‘What happened to him?’ Rex asked.

Susan shrugged. ‘CCTV on the railway station showed him heading towards the study-house to meet his father. He never got there.’

‘And they’re still looking for him?’

‘Someone is, I hope. We did a lot on it at the time, but… teenage frummer boys with skullcaps don’t get quite the same public response as blonde toddlers.’

Susan could sound hard. But Rex knew there was an intensely decent human being underneath. One who’d given him a job when all his other doorways had closed. One who cared about this grimy, fascinating patchwork-quilt of a borough as much as he did. ‘Read the archive,’ she went on. ‘Ellie couldn’t find out much about the community, but I’m not sure how hard she really tried…’

The mention of Ellie Mehta, formerly the paper’s Junior Reporter, had soured the air. She’d left after insisting on a pay rise just as everyone else was taking a cut, and then abruptly gone to work for far less money on the Daily Telegraph. Although Ellie was alive and well, living just down the road in a fashionably horrid part of Hackney and making daily appearances in a major newspaper, she’d become a sort of mythical pariah figure in the office. The regular malfunctioning of the printer was blamed on Ellie Mehta, as was any new computer glitch, and the recent disappearance of a Canon EOS 1DX camera.

‘Anyway,’ Susan said. ‘Let’s meet at six. We’ll refresh at eight tonight, okay, people?’

‘This was supposed to be my afternoon off,’ Terry grumbled, as the boss sailed back into her office. He wiped his forehead. ‘Is anyone else boiling hot?’

‘It has got a lot warmer outside,’ Susan said.

‘In March,’ Brenda said. ‘Climate change.’

The working day had changed in this new, digital age. In addition to meeting the traditional once-a-week deadline for the old Wood Green Gazette – which still existed, as a free ad sheet with a bit of news and comment slapped on the front – they had to update the website every evening, shifting the placement of stories, adding new material in response to the day’s events. A good hour’s work followed that, too, responding to tweets and posts, ensuring all the links were working and the old material correctly archived. Technology was supposed to make everything easier, but Rex found himself working harder than he’d ever done before. If he were honest, he didn’t always mind. It stopped him brooding about what had happened in Cambodia. And before. It meant less time for drinking, too.

Not that he felt much healthier for it. In fact, now that Terry had mentioned it, he did feel hot. Outside, the sun was now shining in a cloudless sky, and down on the High Street below shoppers were strolling about in T-shirts. Rex wasn’t reassured, though. He took the card out of his jacket pocket and read it. It didn’t mention fever. He glanced across and saw that Terry was looking at his own card. They grinned at one another, partly from embarrassment, partly from something else.

‘Why don’t we go out and take a few pictures, then you can get off home?’ Rex suggested. ‘I’m sure you’re aching to get back to your lovely neighbour.’

‘Did I tell you what the scabby bastard said to me last week?’ Terry said, sniffing loudly as he started assembling various bits of camera kit in a canvas bag. ‘Instead of sitting up in your bedroom typing all night, right next to the end of my sodding bed, why don’t you just go downstairs and do it in your living room? And you know what he says?’

‘Why don’t you go sleep in your bathroom?’ Rex said.

The story had already acquired legendary status. As had Terry’s response, which he’d written on a Post-it and stuck in the shared hallway. Meeting the notorious neighbour in the flesh had done nothing to diminish his image – quite the opposite. Except for that final moment in the park, when his prickly manner had evaporated. It hadn’t just been sadness or shock on Dr Kovacs’ face. Rex was sure he’d seen something else. Something closer to fear.

The lower part of Green Lanes had been screened off behind tall metal barriers, forcing Rex and Terry to pick their way southwards through Tottenham. They were less than a mile away from a suspected terrorist murder in a much-frequented park and yet, at least from his seat in Terry’s Vauxhall, Rex could see no sign that the local population knew, or cared.

Things were different once they headed down the broad Edwardian slopes of Stamford Hill into what had been, since the early 20th century, the heartland of the Hasidic Jewish community. The shops were all open as usual: Minsk Housecoats selling the distinctively Hasidic range of long Puffa coats and modest, navy-striped knitwear; Richler Fish with its windows of carp and herring. Plenty of customers were passing in and out: homburg-hatted men in what must have been, for the day, impossibly heavy overcoats; women with bobbed, dark-brown wigs and pushchairs; and kids, dozens, hundreds of kids, everywhere. But outside every Jewish business, as well as several of the vast, beetling villas used as prayer-houses and schools, were the shomrim.

The shomrim were one aspect of the community that did occasionally make the news. Dressed in distinctive fluorescent orange tabards with Hebrew lettering on the back, they acted as a subscriber police force for the community. Occasionally, they were accused of racism when they challenged and chased black and Turkish youths who often hadn’t done anything wrong. More rarely, a shomer became a media celebrity when he interrupted a mugging or rescued a baby. Amidst the rollercoaster of controversy and congratulation, few people recognised the day-to-day business in which the shomrim were engaged, for little or no money: patrolling school crossings and guarding buildings.

‘Last time I seen them all out like this was during the riots,’ Terry croaked. He’d coughed and wheezed the whole way there. ‘This has got to be something to do with the park, hasn’t it?’

‘Let’s ask them,’ Rex said. ‘Can we park up somewhere?’

‘Why don’t you have a go? You’re the one who needs the practice,’ Terry said. Rex ignored him. He shifted about in his seat. He’d gone from feeling hot in the office to shivering in the car. Now he felt as if his hair hurt. What was wrong with them him??

They stationed the car down a side street, next to a small business whose bright, egg-yolk-coloured sign said: ‘Solly Scissorvitz Haircuts: classic, fashion and ritual’. As always before a long walking session, Rex swallowed a couple of painkillers to numb his left foot. Ever since a car accident a decade ago he’d had arthritis in it, and he walked with a limp, which grew more pronounced as the day wore on.

Terry commenced taking snaps with a practised discretion which Rex had never ceased to admire, holding his camera at chest height, and appearing to be examining something on its top control panel whilst actually photographing passers-by. Periodically, to establish his innocence, he took long, wide shots of roofs and sky and street signs. It was a vital subterfuge in this borough, where people’s reasons for being camera-shy ranged from the cultural to the criminal.

Rex looked around for people to talk to. He soon recognised a face amid the lines of guarding shomrim. Outside the Beis Rochel Satmar Girls’ High School stood a short, almost tiny, dark-featured man, legs wide, arms folded, a fedora cocked back high on his head. You might have thought the man slightly comical, if you hadn’t heard of Mordecai Hershkovits.

Hershkovits, whose small ear-curls and modish hat announced him as a scion of the forward-looking, politically active Lubavitch sect, ran classes for the local kids. Not Hebrew classes, but workshops in the deadly art of krav maga. This was a martial art developed by the Israeli Army, in which, it was said, disciples could learn six ways of paralysing an opponent with only their thumbs. True or not, Hershkovits’s offer to teach it to the Stamford Hill boys, and even the girls, had divided the religious Jewish community, and a considerable chunk of those outside it. At the height of the debate, he’d rather spoiled his case – or perhaps strengthened it – by using krav maga on a pair of Bulgarian scaffolders who’d refused to move their truck from the entrance to a Clapton synagogue. Both had spent time in hospital.

Mordecai Hershkovits looked now as defiant as he had on the day he’d received a two-year suspended sentence and 300 hours’ Community Service. Rex had interviewed him then, on an icy morning a few years ago, and found himself liking the man. He wondered if Hershkovits would remember him.

‘Ah, same blue suit,’ the little man said, as Rex approached. ‘When are you going to get a new one?’

‘This is a new one,’ Rex said. ‘I had it made.’

‘Who by? A plumber? What do you want?’ Hershkovits demanded, in a way that might have seemed unfriendly if you didn’t know better.

‘I wondered what people are saying about the Dukovchiner family.’

Hershkovits wiped sweat from his brow. ‘They are not “the Dukovchiner family”. It’s not their surname,’ he said in the same brisk, argumentative tone. ‘You want to print that, go ahead and print it, but you’ll be printing dreck.’

‘I know. I mean – I don’t know what they were called, but I know Dukovchiner wasn’t their name. That’s the name of where their original rabbi came from, right? Like the Lubavitcher follow someone from, er… Lubavitch?’

‘It’s Lyubavichi. And Rebbe. You say Rebbe for a Hasidic leader. Yes. Okay, so you’ve looked at Wikipedia, good.’ He paused to nod to a pair of book-clutching, black-hatted men passing by, so serenely detached from the worldly buzz around them that they seemed almost to float above the ground. ‘What else did your website tell you?’

‘Erm… that Hasidism is a mystical sect formed in Poland in the 17th century, since when it’s split into hundreds of different groups, some focussed on a strict revival of Jewish law, others more on direct communion with God. But all of them expecting the imminent return of the Messiah.’

‘You said that without taking a breath.’

‘I’m good at memorising,’ Rex said. ‘I was an altar boy.’

Hershkovits smiled faintly. ‘The family name was Bettelheim. Yaakov and Chaya Bettelheim. Three children. Eytan, boy of thirteen. Simcha, girl of ten. I don’t know what the baby was called, but it was small. Not even a year old.’ He whistled sadly through his two, slightly prominent front teeth. ‘Their families will be… I don’t know. Destroyed.’

‘They have relatives around here?’

‘Not many, I think. She came from somewhere… I don’t know, maybe Brooklyn. Yaakov’s family are in Manchester. He moved down here because he divorced, I think.’

Although he’d struggled to grasp the unfamiliar names and words in the man’s rapid recital, Rex was pleased. This was useful. Unprintable, of course, before the police had told the relatives. But helpful for his own enquiries. He glanced around for Terry, to ask him to take a photo of Mordecai and saw that he was leaning against a lamppost. He looked exhausted. Rex realised he was starting to feel pretty weird himelf, but he pressed on with the interview.

‘Only three kids, twelve years between the first and the last. Isn’t that quite an unusual family, by Hasidic standards?’

‘Not by Dukovchiner standards.’

‘So are they not really part of the community? I mean, as much as the Lubavitch or the Satmar?’

‘They’re Jews, so they’re part. But…’ Hershkovits frowned, as if caught by a twinge of toothache. ‘Different in a way that if I was to describe them to you so you would understand we would need to start with the forests in Poland in the eighteenth century, and I’m not going to do that because I’m busy here looking after my people this afternoon, okay?’

The line reminded Rex of Moses in the Cecil B. DeMille film: ‘Let my people go.’ You had to admire any man who could talk about ‘my people’ outside of a Hollywood epic and carry it off. ‘So what do your people make of what happened?’

‘We want those Muslim boys caught and punished.’

‘If those Muslim boys did anything.’

‘Sure,’ Hershkovits replied, curtly. ‘So with messages on the TV and the radio every hour, why don’t they come forward, if they did nothing?’ He responded to a crackling call on his walkie-talkie, before adding with a vague wave: ‘By all means quote me, but if you want to talk to Dukovchiner people I’m no use, okay? Try vegetables.’

He left Rex pondering this strange utterance for some time before realising that there was a dimly-lit food shop called ‘Vegetables’, more or less in the direction Hershkovits had waved. Its name – or perhaps another, catchier one – was also written in Hebrew letters, along with a telephone number starting ‘01’, suggesting that telephone calls from the general public were not of crucial importance.

Terry shook his head when Rex mentioned the vegetable shop. ‘Feeling too rough, mate,’ he said, wiping sweat from his forehead across his scalp. ‘I’m going home for a kip. You don’t look too good yourself.’

‘As long as I don’t experience palpitations, blackouts or shooting pains, I reckon I’ll stick at it,’ Rex said.

Terry forced a smile. ‘See you in the nearest A&E.’ As he shouldered the heavy bag, his expression changed. ‘Rex. You don’t honestly think…’

‘What? We’ve been poisoned? Come off it. Look. They’ve got our numbers, and they said if anyone started feeling ill, we’d all be called in. Has anyone called?’

‘Maybe everyone else carked it before they could dial the helpline.’

‘Maybe we’ve got both colds coming on, the weather’s suddenly turned ridiculously sodding hot, and your imagination’s working overtime.’

‘Aye. Mebbe. I’ll email the snaps in.’

Rex watched him go, suddenly worried. Terry seemed an unlikely hypochondriac. And he did feel slightly dodgy himself. Then again he nearly always did, more so lately than ever before. But it had nothing to do with mysterious sprays, everything to do with the arthritis in his foot and the stream of Polish lager and painkillers he took on board every day to numb it. He headed over the busy road to the shop.

Outside ‘Vegetables’ was a brand-new van: a jazzy, modern version of the old, corrugated silver Citroen vehicles you’d sometimes see rusting in the grounds of French farmhouses. Rex wondered if it belonged to the business, which was a shabby place, with grimy windows and a single, fluorescent tube casting a bluish light over the interior.

Inside, it was cool and dank, and a welcome change from the freak Mediterranean weather outside. A huge, yellow-haired man arranged potatoes and carrots and some twisted root vegetables on a series of tables, while a slender woman stared into space behind an ancient till. Rex was greeted by a smell of male sweat, mixed with brewer’s yeast and a top note of soil. The man stared, open-mouthed, as Rex went in, but the woman seemed not to notice.

‘Nice van,’ Rex said to the man. ‘Is it yours?’

After a pause, the man jabbed a thumb in the direction of the woman. ‘Hers,’ he said hoarsely.

Rex smiled vaguely towards the woman, whose face didn’t move. He tried again. ‘How much are the red potatoes?’ he asked, alighting upon the first item he saw. He’d remembered the advice of his first boss, who’d been much given to aphorisms and bons mots: the shopkeeper who can’t sell you anything, won’t tell you anything.

Rex had addressed the question to the large man, but he just continued staring, wiping a hand on his dirty white shirt and silently mouthing words to himself.

‘One pound, one pound,’ said the woman suddenly, as if waking from a trance. She had straight brown hair, a weary tone, and her accent was that of someone who’d spent her life in this part of London.

‘I’ll take two pounds, please.’

‘Yitz.’ At her command, the big man noisily weighed out the required amount, a single tuber at a time, muttering to himself and puffing. The woman returned to her trance, twisting a lapel of her work-coat over and over, while Rex looked around the shop. Its pale green, tiled walls reminded him uncomfortably of a hospital, and were entirely without adornment, save for an ink drawing of a young boy with the same long, tumbling ear-curls that the man wore. There were a few other provisions for sale, besides vegetables: candles in little tin holders, a pile of something or other in neat little brown cones, and some cans covered in Hebrew writing. It was another century in there.

‘Your son?’ Rex asked amiably, pointing at the picture as the potatoes were poured from the weighing-scale dish into a carrier bag. The man shook his head. The woman asked him for two pounds, which Rex counted out and held out to her. The silence grew increasingly tense. She refused the money. He didn’t understand.

‘You don’t want the money?’

‘I don’t want to touch you,’ she said.

He felt himself blush. ‘Sorry.’ He put the money on the counter. ‘I’d read somewhere that you had rules like that, but…’

She held up a finger. She had a long face with wide nostrils – sombre, somehow, but attractive. ‘I’ve got dirty hands.’

Was she teasing him? He wasn’t sure. The shop was so dark and her manner so unfamiliar.

‘Can I ask you something?’ he said. ‘I notice there’s no shomer outside your shop. But they’re everywhere else today.’

The man and the woman exchanged short sentences in Yiddish. ‘We don’t pay shomrim,’ the man said at last, very slowly, brushing some soil from his baggy black trousers. ‘So they don’t stand outside.’ He spoke in a more obviously Yiddish way than the woman, with a guttural r and a luxurious s.

‘When you say “we”, do you mean just this shop, or all the other Dukovchiner shops?’

The woman tutted. ‘There aren’t any other Dukovchiner shops.’

‘You know Dukovchiner?’ asked the man suspiciously.

‘I heard about the Bettelheim family,’ Rex said. ‘Did you know them?’

The woman coughed.

‘Police?’ the man asked.

‘A journalist. My name’s Rex Tracey. From News North London.’ The woman put a hand up to the collar of her high-buttoned blouse. He smiled at her and asked again. ‘Did you know them?’

‘Yes,’ replied the man, adjusting his carrots. The woman – his wife, Rex assumed – admonished him, but he ignored her. ‘I used to work with Yaakov. Quiet man. The wife I don’t know. From Peru.’

‘Peru?’ Rex echoed.

‘Yitzie! She was from Sydney,’ the woman interjected, in a weary way, like a mother tired of a child’s nonsense.

The bear-like man shrugged. He even seemed to do that slowly, with great effort. ‘Some place crazy. She was crazy.’

‘She wasn’t.’

‘She comes in looking like a zombie drug-person!’ Yitzie suddenly roared at his wife, growing red at the neck. ‘Remember? When the little girl ran in the road and she just stood here, staring at the beans?’ The big man paused, out of breath, sucking back the bubbles of saliva that had formed on his lip during his speech. He slowly tapped the side of his head. ‘Crazy.’

‘She has problems,’ the woman said to Rex. ‘Poor health. Three young children to care for. A husband she barely knew before she married him, and her family’s all in Australia! Anyone would stare at beans, don’t you think?’

Rex sensed that she was taking him a short way into her confidence. He smiled. She gave the faintest of smiles back. Yitzie, meanwhile, just sighed – out of words, it seemed, for the moment. He shuffled over and locked the shop door, pulling down a dirty, pale-green blind. As Rex watched the big man lumbering across the shop, he realised there was more to the vegetable offering than spuds and carrots. On another table were long, speckled red runner beans; elsewhere, a stack of crooked, hairy, yam-like items. He was about to ask what they were when Yitzie spoke again.

‘Who is alone here, Rescha?’

Rescha made a disgusted noise. Sensing a further chink in the armour, Rex addressed her directly. ‘Did you know Chaya?’

‘Yes,’ she said, in a thick voice. Rex could see tears forming in the woman’s eyes, because of the dead family, perhaps, or because of the set-to with her husband. ‘I liked her,’ Rescha went on briskly, seeming to put her emotions to one side. ‘But she didn’t come in much.’