0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

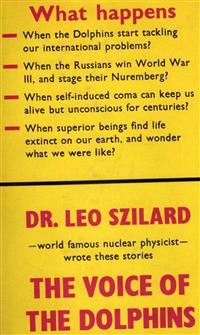

The Voice of the Dolphins derives its title from a television program of that name set up by a group of American and Russian scientists who conspire to save the world. Classic pulp fiction by one of the fathers of the atomic bomb. The lead story tells how the scientists who created bombs might have circumvented politics and created world peace.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Voice of Dolphins and Other Stories

by Dr. Leo Szilard

First published in 1961

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

The Voice Of The Dolphins

and Other Stories

by

Leo Szilard

The Voice of the Dolphins

On several occasions between 1960 and 1985, the world narrowly escaped an all-out atomic war. In each case, the escape was due more to fortuitous circumstances than to the wisdom of the policies pursued by statesmen.

That the bomb would pose a novel problem to the world was clear as early as 1946. It was not clearly recognized, however, that the solution of this problem would involve political and technical considerations in an inseparable fashion. In America, few statesmen were aware of the technical considerations, and, prior to Sputnik, only few scientists were aware of the political considerations. After Sputnik, Dr. James R. Killian was appointed by President Eisenhower, on a full-time basis, as chairman of the President's Science Advisory Committee, and, thereafter, a number of distinguished scientists were drawn into the work of the Committee and became aware of all aspects of the problem posed by the bomb.

Why, then, one may ask, did scientists in general, and the President's Science Advisory Committee in particular, fail to advance a solution of this problem during the Eisenhower administration? The slogan that "scientists should be on tap but not on top," which gained currency in Washington, may have had something to do with this failure. Of course, scientists could not possibly be on top in Washington, where policy, if it is made at all, is made by those who operate, rather than by those who are engaged in policy planning. But what those who coined this slogan, and those who parroted it, apparently meant was that scientists must not concern themselves with devising and proposing policies; they ought to limit themselves to answering such technical questions as they may be asked. Thus, it may well be that the scientists gave the wrong answers because they were asked the wrong questions.

In retrospect, it would appear that among the various recommendations made by the President's Science Advisory Committee there was only one which has borne fruit. At some point or other, the Committee had recommended that there be set up, at the opportune time, a major joint Russian-American research project having no relevance to the national defense, or to any politically controversial issues. The setting up in 1963 of the Biological Research Institute in Vienna under a contract between the Russian and American governments was in line with this general recommendation of the Committee.

When the Vienna Institute came to be established, both the American and the Russian molecular biologists manifested a curious predilection for it. Because most of those who applied for a staff position were distinguished scientists, even though comparatively young, practically all of those who applied were accepted.

This was generally regarded at that time as a major setback for this young branch of science, in Russia as well as in America, and there were those who accused Sergei Dressier of having played the role of the Pied Piper. There may have been a grain of truth in this accusation, inasmuch as a conference on molecular biology held in Leningrad in 1962 was due to his initiative. Dressier spent a few months in America in 1960 surveying the advances in molecular biology. He was so impressed by what he saw that he decided to do something to stimulate this new branch of science in his native Russia. The Leningrad Conference was attended by many Americans; it was the first time that American and Russian molecular biologists came into contact with each other, and the friendships formed on this occasion were to last a lifetime.

When the first scientific communications came out of the Vienna Institute, it came as a surprise to everyone that they were not in the field of molecular biology, but concerned themselves with the intellectual capacity of the dolphins.

That the organization of the brain of the dolphin has a complexity comparable to that of man had been known for a long time. In 1960, Dr. John C. Lilly reported that the dolphins might have a language of their own, that they were capable of imitating human speech and that the intelligence of the dolphins might be equal to that of humans, or possibly even superior to it. This report made enough of a stir, at that time, to hit the front pages of the newspapers. Subsequent attempts to learn the language of the dolphins, to communicate with them and to teach them, appeared to be discouraging, however, and it was generally assumed that Dr. Lilly had overrated their intelligence.

In contrast to this view, the very first bulletin from the Vienna Institute took the position that previous failures to communicate with the dolphins might not have been due to the dolphins' lack of intellectual capacity but rather to their lack of motivation. In a second communiqué the Vienna Institute disclosed that the dolphins proved to be extraordinarily fond of Sell's liver paste, that they became quickly addicted to it and that the expectation of being rewarded by being fed this particular brand of liver paste could motivate them to perform intellectually strenuous tasks.

A number of subsequent communiqués from the Institute concerned themselves with objectively determining the exact limit of the intellectual capacity of the dolphins. These communiqués gradually revealed that their intelligence far surpassed that of man. However, on account of their submerged mode of life, the dolphins were ignorant of facts, and thus they had not been able to put their intelligence to good use in the past.

Having learned the language of the dolphins and established communication with them, the staff of the Institute began to teach them first mathematics, next chemistry and physics, and subsequently biology. The dolphins acquired knowledge in all of these fields with extraordinary rapidity. Because of their lack of manual dexterity the dolphins were not able to perform experiments. In time, however, they began to suggest to the staff experiments in the biological field, and soon thereafter it became apparent that the staff of the Institute might be relegated to performing experiments thought up by the dolphins.

During the first three years of the operation of the Institute all of its publications related to the intellectual capacity of the dolphins. The communiqués issued in the fourth year, five in number, were, however, all in the field of molecular biology. Each one of these communiqués reported a major advance in this field and was issued not in the name of the staff members who had actually performed the experiment, but in the name of the dolphins who had suggested it. (At the time when they were brought into the Institute the dolphins were each designated by a Greek syllable, and they retained these designations for life.)

Each of the next five Nobel Prizes for physiology and medicine was awarded for one or another of these advances. Since it was legally impossible, however, to award the Nobel Prize to a dolphin, all the awards were made to the Institute as a whole. Still, the credit went, of course, to the dolphins, who derived much prestige from these awards, and their prestige was to increase further in the years to come, until it reached almost fabulous proportions.

In the fifth year of its operation, the Institute isolated a mutant form of a strain of commonly occurring algae, which excreted a broad-spectrum antibiotic and was able to fix nitrogen. Because of these two characteristics, these algae could be grown in the open, in improvised ditches filled with water, and they did not require the addition of any nitrates as fertilizer. The protein extracted from them had excellent nutritive qualities and a very pleasant taste.

The algae, the process of growing them and the process of extracting their protein content, as well as the protein product itself, were patented by the Institute, and when the product was marketed—under the trade name Amruss—the Institute collected royalties.

If taken as a protein substitute in adequate quantities, Amruss markedly depresses the fertility of women, but it has no effect on the fertility of men. Amruss seemed to be the answer to the prayer of countries like India. India had a severe immediate problem of food shortage; and she had an equally severe long-term problem, because her population had been increasing at the rate of five million a year.

Amruss sold at about one tenth of the price of soybean protein, and in the first few years of its production the demand greatly exceeded the supply. It also raised a major problem for the Catholic Church. At first Rome took no official position on the consumption of Amruss by Catholics, but left it to each individual bishop to issue such ruling for his diocese as he deemed advisable. In Puerto Rico the Catholic Church simply chose to close an eye. In a number of South American countries, however, the bishops took the position that partaking of Amruss was a mortal sin, no different from other forms of contraception.

In time, this attitude of the bishops threatened to have serious consequences for the Church, because it tended to undermine the institution of the confession. In countries such as El Salvador, Ecuador, Nicaragua and Peru, women gradually got tired of confessing again and again to having committed a mortal sin, and of being told again and again to do penance; in the end they simply stopped going to confession.

When the decline in the numbers of those who went to confession became conspicuous, it came to the attention of the Pope. As is generally known, in the end the issue was settled by the papal bull "Food Being Essential for Maintaining Life," which stressed that Catholics ought not to be expected to starve when food was available. Thereafter, bishops uniformly took the position that Amruss was primarily a food, rather than a contraceptive.

The income of the Institute, from the royalties collected, rapidly increased from year to year, and within a few years it came to exceed the subsidies from the American and Russian governments. Because the Institute had internationally recognized tax-free status, the royalties were not subject to tax.

The first investment made by the Vienna Institute was the purchase of television stations in a number of cities all over the world. Thereafter, the television programs of these stations carried no advertising. Since they no longer had to aim their programs at the largest possible audience, there was no longer any need for them to cater to the taste of morons. This freedom from the need of maximizing their audience led to a rapid evolution of the art of television, the potential of which had been frequently surmised but never actually realized.

One of the major television programs carried by the Amruss stations was devoted to the discussion of political problems. The function of The Voice of the Dolphins, as this program was called, was to clarify what the real issues were. In taking up an issue, The Voice would discuss what the several possible solutions were and would indicate in each case what the price of that particular solution might be. A booklet circulated by The Voice of the Dolphins explained why the program set itself this particular task, as follows:

Political issues were often complex, but they were rarely anywhere as deep as the scientific problems which had been solved in the first half of the century. These scientific problems had been solved with amazing rapidity because they had been constantly exposed to discussion among scientists, and thus it appeared reasonable to expect that the solution of political problems could be greatly speeded up also if they were subjected to the same kind of discussion. The discussions of political problems by politicians were much less productive, because they differed in one important respect from the discussions of scientific problems by scientists: When a scientist says something, his colleagues must ask themselves only whether it is true. When a politician says something, his colleagues must first of all ask, "Why does he say it?"; later on they may or may not get around to asking whether it happens to be true. A politician is a man who thinks he is in possession of the truth and knows what needs to be done; thus his only problem is to persuade people to do what needs to be done. Scientists rarely think that they are in full possession of the truth, and a scientist's aim in a discussion with his colleagues is not to persuade but to clarify. It was clarification rather than persuasion that was needed in the past to arrive at the solution of the great scientific problems.

Because the task of The Voice was to clarify rather than to persuade, The Voice did not provide political leadership, but by clarifying what the issues were in the field of politics The Voice made it possible for intellectual leadership to arise in this field.

A number of political scientists were invited to join the Institute at the time when The Voice of the Dolphins went into operation, and the first suggestion of the dolphins in the political field was made one year later. At that time, the dolphins proposed that the United Nations set up a commission in every South American capital and that these commissions function along the lines of the U.N. Commission that had been in operation in Bolivia since 1950. That commission was advising the Bolivian government on all matters pertaining to the economic welfare of the nation; in addition, it made available trained personnel on whom the Bolivian government could draw, if it wanted to put into effect any of the commission's recommendations.

This proposal of the dolphins was generally regarded as wholly unrealistic. It was pointed out that the governments of the South American nations did not operate in a vacuum, but were subject to political pressures from private interests. It was freely predicted, therefore, that any attempt on the part of a U.N. commission to influence the action of the government to which it was accredited would be frustrated by the influence of the private interests, no matter how sound the advice might be. But such was the prestige of the dolphins that their proposal, formally submitted to the United Nations by Uruguay, was adopted by a two-thirds majority of the General Assembly, after it had been vetoed in the Security Council.

Still, the skeptics might well have turned out to be right, had it not been for the activities of the "special agencies" which the Vienna Institute established in every one of the South American capitals where a U.N. commission was in operation. Even though these special agencies had no policy of their own other than to support the proposals of the local United Nations commissions, and even though they operated on a rather limited budget—none spent more than $15 million a year—without their activities the U.N. commissions could not have achieved their ambitious goals in South America. The amounts which these "special agencies" spent, small though they were, were effective because they were spent exclusively for the purpose of bribing the members of the government in office to do what was in the public interest, rather than to yield to the pressures of private interests.