The Haunter of the Dark

I have

seen the dark universe yawningWhere

the black planets roll without aim,Where

they roll in their horror unheeded,Without knowledge or luster or name.Cautious investigators will hesitate to challenge the common

belief that Robert Blake was killed by lightning, or by some

profound nervous shock derived from an electrical discharge. It is

true that the window he faced was unbroken, but nature has shown

herself capable of many freakish performances. The expression on

his face may easily have arisen from some obscure muscular source

unrelated to anything he saw, while the entries in his diary are

clearly the result of a fantastic imagination aroused by certain

local superstitions and by certain old matters he had uncovered. As

for the anomalous conditions at the deserted church of Federal

Hill—the shrewd analyst is not slow in attributing them to some

charlatanry, conscious or unconscious, with at least some of which

Blake was secretly connected.For after all, the victim was a writer and painter wholly

devoted to the field of myth, dream, terror, and superstition, and

avid in his quest for scenes and effects of a bizarre, spectral

sort. His earlier stay in the city —a visit to a strange old man as

deeply given to occult and forbidden lore as he—had ended amidst

death and flame, and it must have been some morbid instinct which

drew him back from his home in Milwaukee. He may have known of the

old stories despite his statements to the contrary in the diary,

and his death may have nipped in the bud some stupendous hoax

destined to have a literary reflection.Among those, however, who have examined and correlated all

this evidence, there remain several who cling to less rational and

commonplace theories. They are inclined to take much of Blake's

diary at its face value, and point significantly to certain facts

such as the undoubted genuineness of the old church record, the

verified existence of the disliked and unorthodox Starry Wisdom

sect prior to 1877, the recorded disappearance of an inquisitive

reporter named Edwin M. Lillibridge in 1893, and—above all—the look

of monstrous, transfiguring fear on the face of the young writer

when he died. It was one of these believers who, moved to fanatical

extremes, threw into the bay the curiously angled stone and its

strangely adorned metal box found in the old church steeple—the

black windowless steeple, and not the tower where Blake's diary

said those things originally were. Though widely censured both

officially and unofficially, this man—a reputable physician with a

taste for odd folklore—averred that he had rid the earth of

something too dangerous to rest upon it.Between these two schools of opinion the reader must judge

for himself. The papers have given the tangible details from a

skeptical angle, leaving for others the drawing of the picture as

Robert Blake saw it—or thought he saw it—or pretended to see it.

Now studying the diary closely, dispassionately, and at leisure,

let us summarize the dark chain of events from the expressed point

of view of their chief actor.Young Blake returned to Providence in the winter of 1934–5,

taking the upper floor of a venerable dwelling in a grassy court

off College Street —on the crest of the great eastward hill near

the Brown University campus and behind the marble John Hay Library.

It was a cosy and fascinating place, in a little garden oasis of

village–like antiquity where huge, friendly cats sunned themselves

atop a convenient shed. The square Georgian house had a monitor

roof, classic doorway with fan carving, small–paned windows, and

all the other earmarks of early nineteenth century workmanship.

Inside were six–paneled doors, wide floor–boards, a curving

colonial staircase, white Adam–period mantels, and a rear set of

rooms three steps below the general level.Blake's study, a large southwest chamber, overlooked the

front garden on one side, while its west windows—before one of

which he had his desk —faced off from the brow of the hill and

commanded a splendid view of the lower town's outspread roofs and

of the mystical sunsets that flamed behind them. On the far horizon

were the open countryside's purple slopes. Against these, some two

miles away, rose the spectral hump of Federal Hill, bristling with

huddled roofs and steeples whose remote outlines wavered

mysteriously, taking fantastic forms as the smoke of the city

swirled up and enmeshed them. Blake had a curious sense that he was

looking upon some unknown, ethereal world which might or might not

vanish in dream if ever he tried to seek it out and enter it in

person.Having sent home for most of his books, Blake bought some

antique furniture suitable for his quarters and settled down to

write and paint— living alone, and attending to the simple

housework himself. His studio was in a north attic room, where the

panes of the monitor roof furnished admirable lighting. During that

first winter he produced five of his best–known short stories—The

Burrower Beneath, The Stairs in the Crypt, Shaggai, In the Vale of

Pnath, and The Feaster from the Stars—and painted seven canvases;

studies of nameless, unhuman monsters, and profoundly alien,

non–terrestrial landscapes.At sunset he would often sit at his desk and gaze dreamily

off at the outspread west—the dark towers of Memorial Hall just

below, the Georgian court– house belfry, the lofty pinnacles of the

downtown section, and that shimmering, spire–crowned mound in the

distance whose unknown streets and labyrinthine gables so potently

provoked his fancy. From his few local acquaintances he learned

that the far–off slope was a vast Italian quarter, though most of

the houses were remnant of older Yankee and Irish days. Now and

then he would train his field–glasses on that spectral, unreachable

world beyond the curling smoke; picking out individual roofs and

chimneys and steeples, and speculating upon the bizarre and curious

mysteries they might house. Even with optical aid Federal Hill

seemed somehow alien, half fabulous, and linked to the unreal,

intangible marvels of Blake's own tales and pictures. The feeling

would persist long after the hill had faded into the violet,

lamp–starred twilight, and the court–house floodlights and the red

Industrial Trust beacon had blazed up to make the night

grotesque.Of all the distant objects on Federal Hill, a certain huge,

dark church most fascinated Blake. It stood out with especial

distinctness at certain hours of the day, and at sunset the great

tower and tapering steeple loomed blackly against the flaming sky.

It seemed to rest on especially high ground; for the grimy façade,

and the obliquely seen north side with sloping roof and the tops of

great pointed windows, rose boldly above the tangle of surrounding

ridgepoles and chimney–pots. Peculiarly grim and austere, it

appeared to be built of stone, stained and weathered with the smoke

and storms of a century and more. The style, so far as the glass

could show, was that earliest experimental form of Gothic revival

which preceded the stately Upjohn period and held over some of the

outlines and proportions of the Georgian age. Perhaps it was reared

around 1810 or 1815.As months passed, Blake watched the far–off, forbidding

structure with an oddly mounting interest. Since the vast windows

were never lighted, he knew that it must be vacant. The longer he

watched, the more his imagination worked, till at length he began

to fancy curious things. He believed that a vague, singular aura of

desolation hovered over the place, so that even the pigeons and

swallows shunned its smoky eaves. Around other towers and belfries

his glass would reveal great flocks of birds, but here they never

rested. At least, that is what he thought and set down in his

diary. He pointed the place out to several friends, but none of

them had even been on Federal Hill or possessed the faintest notion

of what the church was or had been.In the spring a deep restlessness gripped Blake. He had begun

his long– planned novel—based on a supposed survival of the

witch–cult in Maine —but was strangely unable to make progress with

it. More and more he would sit at his westward window and gaze at

the distant hill and the black, frowning steeple shunned by the

birds. When the delicate leaves came out on the garden boughs the

world was filled with a new beauty, but Blake's restlessness was

merely increased. It was then that he first thought of crossing the

city and climbing bodily up that fabulous slope into the

smoke–wreathed world of dream.Late in April, just before the aeon–shadowed Walpurgis time,

Blake made his first trip into the unknown. Plodding through the

endless downtown streets and the bleak, decayed squares beyond, he

came finally upon the ascending avenue of century–worn steps,

sagging Doric porches, and blear–paned cupolas which he felt must

lead up to the long–known, unreachable world beyond the mists.

There were dingy blue–and–white street signs which meant nothing to

him, and presently he noted the strange, dark faces of the drifting

crowds, and the foreign signs over curious shops in brown,

decade–weathered buildings. Nowhere could he find any of the

objects he had seen from afar; so that once more he half fancied

that the Federal Hill of that distant view was a dream–world never

to be trod by living human feet.Now and then a battered church façade or crumbling spire came

in sight, but never the blackened pile that he sought. When he

asked a shopkeeper about a great stone church the man smiled and

shook his head, though he spoke English freely. As Blake climbed

higher, the region seemed stranger and stranger, with bewildering

mazes of brooding brown alleys leading eternally off to the south.

He crossed two or three broad avenues, and once thought he glimpsed

a familiar tower. Again he asked a merchant about the massive

church of stone, and this time he could have sworn that the plea of

ignorance was feigned. The dark man's face had a look of fear which

he tried to hide, and Blake saw him make a curious sign with his

right hand.Then suddenly a black spire stood out against the cloudy sky

on his left, above the tiers of brown roofs lining the tangled

southerly alleys. Blake knew at once what it was, and plunged

toward it through the squalid, unpaved lanes that climbed from the

avenue. Twice he lost his way, but he somehow dared not ask any of

the patriarchs or housewives who sat on their doorsteps, or any of

the children who shouted and played in the mud of the shadowy

lanes.At last he saw the tower plain against the southwest, and a

huge stone bulk rose darkly at the end of an alley. Presently he

stood in a wind–swept open square, quaintly cobblestoned, with a

high bank wall on the farther side. This was the end of his quest;

for upon the wide, iron–railed, weed–grown plateau which the wall

supported—a separate, lesser world raised fully six feet above the

surrounding streets—there stood a grim, titan bulk whose identity,

despite Blake's new perspective, was beyond dispute.The vacant church was in a state of great decrepitude. Some

of the high stone buttresses had fallen, and several delicate

finials lay half lost among the brown, neglected weeds and grasses.

The sooty Gothic windows were largely unbroken, though many of the

stone mullions were missing. Blake wondered how the obscurely

painted panes could have survived so well, in view of the known

habits of small boys the world over. The massive doors were intact

and tightly closed. Around the top of the bank wall, fully

enclosing the grounds, was a rusty iron fence whose gate—at the

head of a flight of steps from the square—was visibly padlocked.

The path from the gate to the building was completely overgrown.

Desolation and decay hung like a pall above the place, and in the

birdless eaves and black, ivyless walls Blake felt a touch of the

dimly sinister beyond his power to define.There were very few people in the square, but Blake saw a

policeman at the northerly end and approached him with questions

about the church. He was a great wholesome Irishman, and it seemed

odd that he would do little more than make the sign of the cross

and mutter that people never spoke of that building. When Blake

pressed him he said very hurriedly that the Italian priest warned

everybody against it, vowing that a monstrous evil had once dwelt

there and left its mark. He himself had heard dark whispers of it

from his father, who recalled certain sounds and rumors from his

boyhood.There had been a bad sect there in the old days—an outlaw

sect that called up awful things from some unknown gulf of night.

It had taken a good priest to exorcise what had come, though there

did be those who said that merely the light could do it. If Father

O'Malley were alive there would be many a thing he could tell. But

now there was nothing to do but let it alone. It hurt nobody now,

and those that owned it were dead or far away. They had run away

like rats after the threatening talk in '77, when people began to

mind the way folks vanished now and then in the neighborhood. Some

day the city would step in and take the property for lack of heirs,

but little good would come of anybody's touching it. Better it be

left alone for the years to topple, lest things be stirred that

ought to rest forever in their black abyss.After the policeman had gone Blake stood staring at the

sullen steepled pile. It excited him to find that the structure

seemed as sinister to others as to him, and he wondered what grain

of truth might lie behind the old tales the bluecoat had repeated.

Probably they were mere legends evoked by the evil look of the

place, but even so, they were like a strange coming to life of one

of his own stories.The afternoon sun came out from behind dispersing clouds, but

seemed unable to light up the stained, sooty walls of the old

temple that towered on its high plateau. It was odd that the green

of spring had not touched the brown, withered growths in the

raised, iron–fenced yard. Blake found himself edging nearer the

raised area and examining the bank wall and rusted fence for

possible avenues of ingress. There was a terrible lure about the

blackened fane which was not to be resisted. The fence had no

opening near the steps, but round on the north side were some

missing bars. He could go up the steps and walk round on the narrow

coping outside the fence till he came to the gap. If the people

feared the place so wildly, he would encounter no

interference.He was on the embankment and almost inside the fence before

anyone noticed him. Then, looking down, he saw the few people in

the square edging away and making the same sign with their right

hands that the shopkeeper in the avenue had made. Several windows

were slammed down, and a fat woman darted into the street and

pulled some small children inside a rickety, unpainted house. The

gap in the fence was very easy to pass through, and before long

Blake found himself wading amidst the rotting, tangled growths of

the deserted yard. Here and there the worn stump of a headstone

told him that there had once been burials in the field; but that,

he saw, must have been very long ago. The sheer bulk of the church

was oppressive now that he was close to it, but he conquered his

mood and approached to try the three great doors in the façade. All

were securely locked, so he began a circuit of the Cyclopean

building in quest of some minor and more penetrable opening. Even

then he could not be sure that he wished to enter that haunt of

desertion and shadow, yet the pull of its strangeness dragged him

on automatically.A yawning and unprotected cellar window in the rear furnished

the needed aperture. Peering in, Blake saw a subterrene gulf of

cobwebs and dust faintly litten by the western sun's filtered rays.

Debris, old barrels, and ruined boxes and furniture of numerous

sorts met his eye, though over everything lay a shroud of dust

which softened all sharp outlines. The rusted remains of a hot– air

furnace showed that the building had been used and kept in shape as

late as mid–Victorian times.Acting almost without conscious initiative, Blake crawled

through the window and let himself down to the dust–carpeted and

debris–strewn concrete floor. The vaulted cellar was a vast one,

without partitions; and in a corner far to the right, amid dense

shadows, he saw a black archway evidently leading upstairs. He felt

a peculiar sense of oppression at being actually within the great

spectral building, but kept it in check as he cautiously scouted

about —finding a still–intact barrel amid the dust, and rolling it

over to the open window to provide for his exit. Then, bracing

himself, he crossed the wide, cobweb– festooned space toward the

arch. Half–choked with the omnipresent dust, and covered with

ghostly gossamer fibers, he reached and began to climb the worn

stone steps which rose into the darkness. He had no light, but

groped carefully with his hands. After a sharp turn he felt a

closed door ahead, and a little fumbling revealed its ancient

latch. It opened inward, and beyond it he saw a dimly illumined

corridor lined with worm–eaten paneling.Once on the ground floor, Blake began exploring in a rapid

fashion. All the inner doors were unlocked, so that he freely

passed from room to room. The colossal nave was an almost eldritch

place with its drifts and mountains of dust over box pews, altar,

hour–glass pulpit, and sounding–board and its titanic ropes of

cobweb stretching among the pointed arches of the gallery and

entwining the clustered Gothic columns. Over all this hushed

desolation played a hideous leaden light as the declining afternoon

sun sent its rays through the strange, half–blackened panes of the

great apsidal windows.The paintings on those windows were so obscured by soot that

Blake could scarcely decipher what they had represented, but from

the little he could make out he did not like them. The designs were

largely conventional, and his knowledge of obscure symbolism told

him much concerning some of the ancient patterns. The few saints

depicted bore expressions distinctly open to criticism, while one

of the windows seemed to show merely a dark space with spirals of

curious luminosity scattered about in it. Turning away from the

windows, Blake noticed that the cobwebbed cross above the altar was

not of the ordinary kind, but resembled the primordial ankh or crux

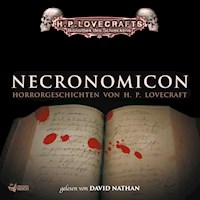

ansata of shadowy Egypt.In a rear vestry room beside the apse Blake found a rotting

desk and ceiling– high shelves of mildewed, disintegrating books.

Here for the first time he received a positive shock of objective

horror, for the titles of those books told him much. They were the

black, forbidden things which most sane people have never even

heard of, or have heard of only in furtive, timorous whispers; the

banned and dreaded repositories of equivocal secret and immemorial

formulae which have trickled down the stream of time from the days

of man's youth, and the dim, fabulous days before man was. He had

himself read many of them— a Latin version of the abhorred

Necronomicon, the sinister Liber Ivonis, the infamous Cultes des

Goules of Comte d'Erlette, the Von unaussprechlichen Kulten of von

Junzt, and old Ludvig Prinn's hellish De Vermis Mysteriis. But

there were others he had known merely by reputation or not at

all—the Pnakotic Manuscripts, the Book of Dzyan, and a crumbling

volume of wholly unidentifiable characters yet with certain symbols

and diagrams shuddering recognizable to the occult student.

Clearly, the lingering local rumors had not lied. This place had

once been the seat of an evil older than mankind and wider than the

known universe.In the ruined desk was a small leatherbound record–book

filled with entries in some odd cryptographic medium. The

manuscript writing consisted of the common traditional symbols used

today in astronomy and anciently in alchemy, astrology, and other

dubious arts—the devices of the sun, moon, planets, aspects, and

zodiacal signs—here massed in solid pages of text, with divisions

and paragraphings suggesting that each symbol answered to some

alphabetical letter.In the hope of later solving the cryptogram, Blake bore off

this volume in his coat pocket. Many of the great tomes on the

[...]