7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

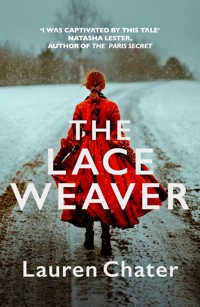

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

TWO WOMEN SEPARATED BY CENTURIES, THEIR LIVES DRAWN TOGETHER BY A BEAUTIFUL SILK DRESS Textiles historian Jo Baaker returns to the Dutch island where she was born, to investigate the provenance of a valuable seventeenth-century silk dress retrieved from a sunken shipwreck. Her research leads her to Anna Tesseltje, a poor Amsterdam laundress who served on the fringes of the Dutch court. But how did Anna come to possess such a precious dress? Jo is convinced the truth lies hidden between its folds, but as she gets closer to Anna's history, haunting details of her own past emerge.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 519

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

3

THE WINTER DRESS

Lauren Chater

4

5

For my husband Michael, who journeyed with me.

CONTENTS

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The Winter Dress was inspired by a collection of seventeenth-century artefacts discovered off the coast of Texel, a small island in North Holland in 2014. The most unusual artefact retrieved by divers – a well-preserved seventeenth-century silk dress – was later identified by leading dress historians as one of the most significant and exciting discoveries in textiles history. The story of the dress’s discovery spread to the Dutch mainland where it became an international sensation, attracting the attention of conservators and academics eager to unravel its mysterious origins. After reading an article about the dress published in The New Yorker, I instantly knew I wanted to write about it. Something about its ethereal, unearthly beauty captured my imagination and I was intrigued by the life of the woman who wore it as well as her fate.

In June 2019, I travelled to the Netherlands to interview the Texel divers who made the discovery as well as the historians and specialists charged with preserving the artefacts. Their theories formed the basis of The Winter Dress, however I have taken the liberty of inventing an entirely new cast of characters and fictionalising dramatic turning points to enhance the novel’s themes. I’m indebted to the staff at the Kaap Skil Museum on Texel (particularly Alec Ewing 7and Corina Hordijk), as well as members of the Texel Diving Club, for showing me around the island and sharing their stories. Thanks also to Rob van Eerden for allowing me to view the dress – a spellbinding and unforgettable experience I drew on many times during the writing of this novel.

Introductory note for The Winter Dress

Alec Ewing, Head Curator, Kaap Skil Museum, Texel

In 2014, local divers from the Dutch island of Texel stumbled onto a unique discovery: a nearly complete satin gown, dating back to the seventeenth century. The gown was found in a broken chest, located near the main mast of a wrecked vessel. Remains of other textiles were found alongside it, while nearby chests held silverware and rich book bindings. Locals had already given it a name: the Palmwood Wreck, named after the previously discovered cargo of boxwood.

The existence of the wreck itself is not unusual. The seas surrounding Texel are in fact littered with shipwrecks. Historically, the island was strategically located in the middle of several trade routes, with the eastern coast serving as a busy roadstead during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Several dozen wrecks have reappeared from beneath the sands in the last few decades. Due to their poor state, few can be historically identified. While parts of the rigging, weaponry and robust cargo can still be salvaged, textiles are a big exception. As organic material is usually the first to disintegrate, a decayed sock or sleeve is a rare discovery.

While all are heritage sites that yield important information about Dutch history, none have come close to 8matching the value of these discovered textiles. Remarkably, this gown has survived a nearly 400-year-long stay below the surface of the water rather well. While no undergarments remain, the gown itself is almost completely whole. Its silk still carries a shine and its floral patterning still clearly stands out. Its colours are reds, browns and cream, though it has clearly been contaminated by the dyes from other fabrics stored in the same chest. Parts of those other garments have been salvaged as well, though none are as complete.

Extensive research into the gown and the rest of the collection has been ongoing since 2016. Why did these textiles survive? Are they part of one wardrobe with a single owner? What was the ship’s name, and how was it lost? Not all answers have been found, but an image is taking shape: of a well-armed Dutch merchantman returning from the Mediterranean between about 1650 and 1670. Whatever its name, that ship took several chests filled with valuable goods on board somewhere along the way. They are rich, worldly, personal, and often feminine. Some carry an English connection, others a Dutch one, and some are more exotic. The textiles and silverware would not look out of place in the highest social circles of Western Europe, but who in Holland would be wearing a kaftan?

Though much room is still left for speculation, the value of the collection is already hard to overstate. In many ways, it is shining new light onto fashion, travel and material culture in North-western Europe during the seventeenth century and is spurring on new insights and research initiatives. Highlights of the collection will be put on permanent display in Museum Kaap Skil on Texel in 2022.9

1

Jo2019

The first thing I recall about that day is not the image of the dress nor Bram’s phone call. It’s the man’s clothes, arranged in a neat pile halfway up the beach. A pair of shorts folded over canvas sneakers. A white shirt fluttering in the breeze. The stranger had removed his watch before he entered the water. In the gathering heat, its glass dial blazed like a second sun. Two grim-faced paramedics knelt on the sand packing up their equipment, while a uniformed cop directed curious onlookers away from the poor man’s body, partially concealed under a plastic sheet.

I imagined the fleshy contours and rich, sun-tanned hues of the victim’s face – not the blanched, sunken look he’d worn when the lifeguards dragged him out of the surf, but that earlier version of him, the living, breathing one that had escaped my notice. After arriving at Bondi Beach an hour ago, I’d run as quickly as I could towards the water, paddling hard until I felt the vertiginous pull of the current grip my legs and arms, the sandy shelf giving way to a bottomless blue. I floated, waiting for the sea to work its magic and ease the knotted tension in my neck. 11

I’d spent most of the previous day hunched over my laptop, attempting to finish writing my book. The past eight months had taught me that it was one thing to write a dissertation on cultural dress theory and quite another to convert it into a digestible piece of creative non-fiction people might actually want to read. Before leaving my job as a lecturer at the London Metropolitan University, I’d applied for, and been accepted into, a research fellowship program at Sydney University. I’d written most of the first draft of my textiles book in a tiny office over-looking the university quadrangle, knocking out twelve chapters within six months in a kind of frenzy. Then, for reasons I found hard to explain to the Dean and my colleagues, my progress had stalled.

I had started sleeping badly, my dreams brimming with voices speaking all at once, as if half a dozen radio frequencies had been spliced together to torture me. Some of the voices I recognised as belonging to people I knew but many of them remained stubbornly vague. They prattled on about the most mundane subjects – what they were planning to eat for dinner, what mischief their children got up to, the kind of house they hoped they could afford once the mortgage rates fell. I’d tried everything to tune them out – meditation before bed, half a Valium before dinner. I even banned caffeine from my diet, although my resolution lasted less than a fortnight (the coffee withdrawals made me so irritable that my aunt, Marieke, insisted I resume the habit). And then, just as suddenly as they had started, the bad dreams lifted. For the past few days, my head had been clear. No more voices, no more headaches. Just peace. The terms of the 12university fellowship stipulated that the book I was working on needed to be ready for publication within a year. Meeting the deadline would be challenging after my health issues but, if I worked hard, not impossible. I’d pushed myself yesterday to regain some momentum. Now I was paying for it.

My neck had felt poker-stiff, the tendons stretched as taut as piano wire. Every turn of my head sent a ripple of pain shooting down a labyrinth of nerve-endings into my spine. I could have arranged a massage but that would have meant putting my body in a stranger’s hands and making the dreaded small talk, an ability I’d always admired in others since it was a skill I felt I lacked. The beach had seemed a far safer bet.

Marieke insisted the cure for any ailment was salt water. She swore by the restorative benefits of a good cry, vowing she always felt better afterwards. But crying had never affected me that way. I hadn’t even cried the night two police arrived from the Dutch mainland on Texel, the small island where I lived, to tell me that my parents’ bodies had been found in an isolated swamp in Southern Holland. Too numb and shocked to accept what they were trying to say, I assumed the tears would come later. I waited for them to arrive, the way I expected my parents to walk through the door again, their voices raised in perpetual argument over some slight committed years ago. But they never did.

When Marieke had showed up to make the funeral arrangements and organise the adoption paperwork so I could leave Holland and return to live with her in Australia, I’d asked if she thought it was odd I was yet to cry over my parents’ deaths. What if I was one of those strange criminals you read about in the news – a person devoid of empathy 13who tortures others without remorse? But Marieke had assured me grief has its own timeline.

‘Your parents died in a freak accident, Josefeine, something nobody could have predicted. It will take time for the shock to wear off. But one day, you will cry, and when that moment comes I’ll be there to console you.’

I’d never quite worked up the courage to tell her she was wrong.

I let the ocean cradle me and, after half an hour’s gentle rocking elapsed, raised my head and glanced back towards the shore. The southern end of the beach was already packed, although it was not yet nine. Teenagers splashed playfully in the shallows and a pod of surfers wove in and out of sight, their boards spearing the waves as neatly as needles through cloth. Bondi had been packed with tourists and locals for as long as I could remember. I could still recite the number of the bus that had conveyed me to the city interchange during the summer holidays, I could picture it wheezing to a stop outside Marieke’s Marrickville terrace where she’d brought me to live. There was a particularly cranky bus driver on the 412 route who always shouted at me to hurry, then sighed as if greatly put upon when I fumbled the unfamiliar coins. I once heard him mimic my Dutch accent to another passenger, exaggerating the vowels like a toddler learning their first rhyme. I accepted his mocking without complaint but promised myself I would work hard to be rid of the accent, casting off the fragments of my old life like an ill-fitting shell.

How strange everything had seemed in those early months. Even the light was different. It stung my eyes if I stared too long at the waves and it painted glowing after-images 14of striped towels and beach umbrellas on the back of my eyelids. That particular kind of light – that bright, unforgiving Australian sunshine – was a stark contrast to the soft ambience of my Northern European childhood. It marked, distinctly, the two phases of my early existence and allowed me to press on without worrying too much about the past. Moving to Australia with the only person in my family brave enough to leave the island of Texel, where generations of Baakers had always lived, seemed like a wild adventure, the fulfilment of a destiny I’d always sensed waiting. I felt reborn, as if I’d been given a second chance. I knew I had to be tough to survive and I wasn’t about to throw away my hard-won independence by dwelling on things that might have been.

I was still floating on my back when the screaming began. A woman’s voice, shrill, panicked. I’ve never been scared of sharks – you can’t be when you dive as regularly as I do. You’ve got more chance of being caught in a rip and washed out to sea than you do of ending up as a white pointer’s lunch. But the screaming rattled my nerves so I started paddling in, using the current to propel me through the surf. As I neared the shore, two lifeguards emerged, hauling something wet and heavy between them, water streaming off their shoulders and necks as they fought the tide. Spectators standing in the shallows watched the drama unfold, their faces frozen as if turned to stone.

I staggered back onto the sand just as the lifeguards laid the man down and began performing CPR. By the time the paramedics arrived, it was obvious to everyone that the man was gone. His profile was a pallid sculpture carved from bleached bone, save for his nose and lips which were purple-tinged: classic 15signs of oxygen deprivation. A few months after my parents died, I became obsessed with drownings and near-drownings. It was a morbid fascination; something I’m now a little ashamed to admit, although in my defence, I was sixteen and my whole world had been upended by their unexpected passing.

When I had first arrived in Australia, Marieke was working as an administration assistant in a community art gallery. It was the summer holidays. I was yet to make any friends. Each morning, I followed Marieke into town and she dropped me at the State Library. I spent hours there poring over books and old newspapers and dog-eared magazines, indulging in my strange infatuation. I learned that there are five stages of drowning, that clinical death can occur after four minutes of complete submersion. I learned that even after successful resuscitation, some victims continue to experience breathing difficulties, hallucinations and confusion. Approximately ninety per cent of drownings occur in freshwater lakes, rivers and swimming pools. The remaining ten per cent take place in sea water.

People who have drowned and been brought back describe the experience as ‘surreal’. They liken it to sitting in a darkened theatre, watching themselves as actors going through the motions on screen. First comes disbelief – the mind and body struggling for dominance, one refusing to acknowledge how serious the situation is while the other searches frantically for a source of oxygen, rapidly leading to a semi-conscious state. Doctors describe this as ‘the breaking point’ – the moment where chemical sensors inside the body trigger an involuntary breath that drags water into the windpipe. After that comes shock and then the grave 16acceptance of their inevitable fate: a kind of surrendering.

These accounts had made me shiver even as I devoured them. Was this what my parents experienced in their final moments? The enduring mystery – that I would never know their last thoughts – had haunted me well into adulthood. There was one thing I was sure of, though. When death had rushed headlong into the salt plains of Saeftinghe, flooding the sea asters and scurvy grass verging the isolated hiking trail where they’d chosen to walk that day without a guide, their last moments hadn’t been spent worrying about what would happen to me. I was their burden. They’d always made that perfectly clear.

Swinging my bag over my shoulder, I walked towards the carpark, passing the small group keeping silent vigil over the man’s body. There was nothing to be done. The police would check his identification and notify his next of kin as they had when my parents had passed. I had been spared the horror of having to identify them because my best friend’s father offered to do it for me. I was grateful to him then, as I was grateful for a good many things Bram’s family did for me, providing stability where none existed.

I opened my car door and sat in the driver’s seat. As I lifted the key to the ignition, a great heaviness overcame me. My hand shook. I stabbed at the ignition, came up short. Tried again. Failed. Resigned, I let the key drop into my lap and took a few deep, steadying breaths, letting my mind wander to the images I’d been analysing yesterday. This kind of procedural sifting never failed to calm me. Thinking about clothes had always offered sanctuary, a safe place to retreat to when the harsh realities of life threatened to overwhelm. The chapter I’d 17been working on yesterday had focused on the impact of the English Civil War on seventeenth-century European fashion. I’d managed to track down a number of suitable examples of formal male dress, including some grisly images of the blood-stained shirt King Charles I had been wearing when he lost his head on the execution block outside the Banqueting Hall at Whitehall. There was also an exquisitely embroidered men’s hunting jacket, wearer unknown. While little was known about the origins of the embroidered jacket, the King’s shirt had become a relic after his death, understandably infused with the horrible import of deliberately killing the God-ordained English monarch: a kind of existential buyer’s regret. What I needed now were real examples of gowns – not something painted, since portraits couldn’t always be relied upon to convey the precise ways clothes sat on a person’s figure, but tangible artefacts through which I could explore the complexities of women’s lives. Unfortunately, few examples of clothing from that period existed now. The ones that did were housed in archives and museums far from Sydney. The Met in New York and the Musée de la mode et du textile in Paris held some extraordinary pieces of women’s clothing in their collections but organising to view them or requesting permission to reprint the images taken by their official photographers would take time.

My phone buzzed in the bottom of my bag, snapping me out of my contemplation. I fished it out and unlocked a message from an unknown number and drew in a small breath as a photograph of a late Jacobean court dress flickered to life on the screen. The colour was striking: rich ox-blood, overlaid with burnished copper. The elaborately embroidered fabric patterned with pale florets, caterpillars 18and bees, a common motif signifying birth, death and fertility. There was some obvious damage. A dark stain had turned the laces black, indicating the corrupting presence of iron mordant. Once prized as a fixative that brought out the glorious shades of natural dye, the metal salts could weaken the chemical structure of fabric over time.

I had no doubt that close examination under a micro-scope would reveal tiny holes in the delicate fabric. The damage would inevitably worsen, spreading like spores of mould on cheese until the entire composition eventually broke down. For now though, the undamaged parts of the brocade shimmered like fish scales, illuminated by an arc of rainbow light as if someone had sponged the panels with water to bring out the peculiar, dazzling shine of gold thread ribboned throughout the weft. The hem and sleeves were fringed with yellow-starched reticella lace, very fine meshwork which must have taken hours of back-breaking labour to produce. Excitement bubbled through me.

Under the image on my phone, the sender had written in Dutch: Wat denk je, Feine?

What do you think, Feine?

Only a handful of people knew me from my Texel days and only one, apart from Marieke, was bold enough to use my childhood nickname. Bram, is that you?

It’s me,he wrote back. I’ve changed phones. Glad this is still your number! Did you get the photo?

I did! What’s the time there?

A little after 5 a.m.. I’m at the clubhouse in Oudeschild. Sem’s here, too. He says congratulations on that piece you wrote for The New Yorker! We bought three copies and 19had one framed for the display room. You’re famous, Feine!

The article, a watered-down version of my PhD, had been published five years ago to coincide with the opening of an exhibition on Tudor women hosted by a London gallery. I’d argued that the intimate items of Elizabeth Tudor’s boudoir actually belonged to her lover, a woman. One of her ladies-in-waiting, to be precise, the daughter of a wealthy landowner who had made his fortune selling acres of oak forest cut down and repurposed into a fleet of naval ships. The story had been picked up by international media outlets and syndicated across the globe. It was the only article I’d ever written that had gone viral and, looking back, I was woefully unprepared for the fallout. For a few months, my phone was clogged with weekly messages from journalists demanding exclusive interviews or armchair historians wanting to discuss their own Tudor theories. Worst of all was the avalanche of hate mail I received from die-hard monarchists who despised the suggestion of homosexuality in any members of the institution, living or dead. The whole experience had left me wary of committing too early to a theory and espousing it publicly before I was mentally ready to deal with the outcome.

Tell me about the dress, I wrote.

We were diving a wreck yesterday out near De Ezei – a galleon, a big old grandmother ship. She’s usually under a layer of mud but a storm uncovered her. Blew all the mud and sand away. Nearly blew us away! There was a sealed chest on the upper deck. We had to break it open with a knife. Then the wind picked up again and the visibility turned to shit so we grabbed everything we could and hauled it back to our boat. Sem unrolled the fabric and we 20realised it was a dress. We couldn’t decide what to do with it. Then somebody remembered your article. I haven’t even shown you the other stuffyet. Stand by.

I watched three tiny circles revolve while more photos loaded. The first was a seventeenth-century lice comb on a black background, the blond wood purled with knots, the edges needled with sharp, uneven teeth. I’d handled a similar one years ago in a lab in Oxford, cleaning the wood with a fine sable paintbrush before prising the desiccated bodies of centuries-old lice out of the tines. Next came a four-sided drawstring purse, the exterior worn so thin that the hard leather scaffold showed through the patched velvet like exposed cartilage. A woman would have tied those purse strings around her waist and stored her personal items inside – a sewing kit, perhaps, or a herbal pomander, something to ward off the foul stench of the city streets. The final image revealed a scattering of crimson carpet fragments piled up beside a damp leather book cover. The book’s pages had long since dissolved, leaving just the fragile bindings. A heraldic crest was stamped on the leather, but the camera had failed to capture the finer details so all I could make out was a blurred shape resembling a sword or a staff hemmed inside a scrolled cartouche.

I waited but there were no more photos, only a text message. So? What do you think of our treasures?

I hesitated for exactly ten seconds before pressing the tiny telephone logo. Bram picked up on the second ring. His voice was warm and familiar, despite the oceans and years separating us.

‘Feine! Or should I call you Doctor Baaker?’

I could tell he was grinning. I pictured his sparkling eyes 21and lopsided grin, the way his chipped right tooth always snagged on his bottom lip – the legacy of an adolescent encounter with a 40-pound scuba tank. I tried to remember when we’d last spoken. It must have been around four years ago. He’d called to invite me to a school reunion which I’d declined to attend, although I could have easily flown from London, where I was based, to Amsterdam and arranged a hire car. The reunion was to be held in the college gymnas-ium of our old high school on the Dutch mainland. When I’d lived on Texel, the student population was so insignificant that the local government didn’t feel they could justify paying a teacher. Instead, each morning Bram and I had taken the ferry together, crossing the deep, cold waters of the Marsdiep, the tidal race that thundered between Texel and the coastal village Den Hoorn, providing the only access to the island except by air.

At sixteen, Bram had towered over the sixth-form boys and some of the teachers, too. He was smart, a joker, always ready to laugh at his own expense. In the summer holidays, he could be found in the backroom of the scuba-diving shop his father owned, filling air tanks and washing wetsuits and kitting out the tourists with snorkels and masks. We’d lost touch a bit after I moved away, eventually reconnecting in our mid-twenties when Bram tracked me down via the staff website of the V&A Museum where I was working. He’d sent a cautious email, wanting to know if I remembered him. He had recently opened a pizza shop in Den Burg with his brother and was quick to reassure me he understood if I preferred not to reply. It might be too painful, after everything I’d been through. But I’d replied almost at once. Of course I remember you! I’d written, before going on to 22describe my work sourcing a series of traditional masque gowns to be displayed alongside the museum’s extensive collection of seventeenth-century Stuart furniture.

My enthusiastic response to Bram’s email surprised me. It was like rediscovering a fragment of myself I thought I’d lost. We’d always joked about running away, escaping the island and carving out a life for ourselves in South America or, yes, even Australia. Somewhere hot, where the long winter months couldn’t touch us. But somehow, despite the banter, I always knew he’d stay behind. Our friendship had been purely platonic and I’d trusted him with my life. We’d often dived together. Immersed between thirty metres of water and the ocean floor, we’d had only each other to rely on. The trust we’d built over our years of diving together had never faded, nor had the promise we’d once made never to lie to one another, if we could help it.

‘It’s just Jo,’ I said. ‘Not Doctor Baaker. Or Feine, if you prefer, although nobody’s called me that in a long time. As for the artefacts, I think they’re extraordinary. I’m not exaggerating when I say this could be a huge bloody deal, Bram. We’re talking international coverage, the pick of the world’s very best museums, the most outstanding textiles conservators and researchers.’

I paused to draw breath, aware of the budding excitement, the blood whooshing through my body, spurred on by my erratic, febrile pulse. I recovered myself enough to ask where the artefacts were.

‘The purse and the comb are in the display room. The dress is hanging up in the bathroom. We hosed it down to get the mud off.’ 23

‘Hosed it down?’ I sputtered, unable to conceal my shock. The idea of that fine silk surviving centuries of potential damage only to be blasted by chemically infused tap water and stuck on a wire coathanger to dry made me feel queasy. The temptation to scold burned. Mishandlings are common in the archaeological field. Any artefact dating back fifty years or more was bound to contain a litany of improperly applied conservation techniques, accidental mishaps and unsuitable storage methods. Sometimes there was a record, a series of notes kept alongside the item that could provide clues to its future management while telling the story of its past. But Bram and his brother were not conservators. They would not have known, for example, that the best way to store a dress retrieved from the bottom of the ocean was probably to keep it submerged in water for as long as possible, in a dark room. Oxygen, light and fluctuations in temperature were anathema to old fabrics.

As soon as that dress hit the surface, the process of deterioration would have begun. Invisible at first, the damage would eventually manifest as dark stains and tiny tears in the fibres of the fabric as the seams crumbled into a powdery dust. The leather book casing, already fragile, would probably suffer a similar fate. All too often, I’d taken possession of textiles that had warped due to high levels of humidity. Under such conditions, a fabric’s surface could be permanently deformed mere months after exposure, leaving the artefact completely unrecognisable. Antique cellulose, once used to glue together fabric seams, was viewed by rapacious silverfish as a free meal, while an infestation of carpet beetles, prized by conservators for stripping skeleton 24specimens of hard-to-reach flesh, could destroy an entire collection of historical garments in less than a week. Carpet beetles were voracious eaters, chewing through silk, fur, wool and leather indiscriminately. The discovery of an outbreak within a museum was always met with a flurry of anxious activity as conservators and curators rushed around trying to ensure the affected clothing was quarantined and frozen to kill the bugs and prevent the damage spreading.

Bram knew none of this. While well intentioned, his expedition to retrieve items from the wreck was at best reckless, at worst deliberately provocative. I could have murdered him for being so foolish. But then I remembered all the times he’d shared his lunch with me in the schoolyard and the countless nights he’d slept on the floor of his bedroom, gifting me the comfortable bed so I’d be well rested when we rose at dawn the next day to go diving. I felt my frustration ebb. What was done was done. The important thing now was to ensure the artefacts were stabilised without subjecting them to further damage.

I explained to him that, based on what I could see, the items appeared to be early to mid-seventeenth century. The cargo had probably belonged to a merchant’s ship, one of the many that had been lost on the famous Texel Roads during that period. The Roads had been a popular shipping route used by Dutch sailing vessels to import wood from Norway and grain from the Baltic. The fabric for the dress could have been woven in Holland by Amsterdam silk-weavers or a family of French Huguenots who’d fled to London to escape religious persecution after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Or it could be Bursa silk, spun during the 25Golden Age of the Ottoman Empire when Turkey and Syria competed with China and Persia to supply fine textiles for use in both clothing and household furnishings. Intricate floral patterns woven onto silk panels in gold and silver thread were just as likely to be found on dresses as on cenotaphs, the waxy pomegranates and delicate peony blossoms twined through Qur’anic verses honouring the dead. ‘What you need,’ I said, ‘is a professional who’ll be able to stabilise the artefacts and make a proper assessment.’

‘Great. So, when are you available?’

‘You want me to do it?’

‘Of course! Why do you think I made contact?’

Ouch. That stung. Maybe my rejection of Bram’s invitation had bothered him more than I thought. He’d asked me to visit the island on other occasions but I’d always found some excuse. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to see him; I valued our friendship possibly more now than when we were children. While memories of my parents were like vague shadows glimpsed through smoky glass, the ones I retained of Bram and his family were vividly clear. His occasional updates were a reminder that I hadn’t sprung into the world fully formed at the age of sixteen. I had a past, a history, even if it was one I selectively chose not to think about. Cocooned in the cosy, protective warmth of Bram’s family, of which I was an honorary member, I’d had no reason to delve deeper into those experiences I’d shared with my parents that were potentially unstable and served no good purpose. Occasionally, if I was exhausted, my mind would seek them out, returning to old hurts and bitter accusations, replaying them over and over like scenes 26in a movie. Reprisal never brought relief. Bram had never harassed me to return to Texel. He had always accepted my excuses with mild diplomacy. Now I wondered whether the needle on his internal bullshit meter had been swinging wildly the whole time we were speaking, the current of my lies forcing the needle all the way to the right.

‘I’m not a trained conservator,’ I warned him. ‘I can do the rudiments – stabilise the items, assess the damage. My specialty is illuminating the cultural significance of an article of clothing, tracking down its origins. With luck, I can unlock certain key aspects of the wearer’s identity, the time and place where they were born, the things that shook their world – religious wars, revolutions, scientific advancements. I’d love to help, but we’re going to need to get someone else on board with experience in other aspects of conservation, not just textiles.’

I paused, mentally sifting through the profiles of former colleagues. My contact list was a little rusty since I’d moved back to Australia to work on my book, but I could think of only one person who could fulfil all our requirements.

Liam Pinney was one of the best conservators around. We’d known each other since we were undergrads and had kept up our friendship all the way through our admittedly colourful careers. Six years ago, we’d been asked by the London Met, where we were both working, to assess a collection of sixteenth-century French tapestries and silk brocade nightgowns discovered by a wealthy octogenarian in the attic of her Cambridge castle. The woman had contacted the London Met to request an assessment and they’d sent Liam and me out to investigate the artefacts. We ended up publishing our findings at the same time, but the university 27chose to promote Liam’s research into the tapestries, while my paper championing the delicate gowns as some of the earliest and best examples of royal dress was relegated to second and third-tier publications. This had resulted in a depressing lack of citations.

I’d confronted the Dean of Social Sciences, who’d said nightgowns simply weren’t in the same league as priceless tapestries. His insinuation, that the study of women’s fashion was unworthy of any real academic distinction, was one of the reasons I left academia shortly afterwards, vowing never to return.

Liam had rung me to apologise straight after I’d stormed out of the Dean’s office.

‘I’m so sorry. If I’d known what the university was planning, I’d have insisted on combining our research and publishing it together. You’ve got to believe me, Jo.’

He’d sounded so earnest, it was impossible not to forgive him. Last I’d heard, he’d been teaching at the Glasgow School of Art while working on his own research about the ‘self-made man’ and the rise of dandyism in early eighteenth-century Europe.

‘I have someone in mind,’ I told Bram. ‘There may be some complications over ownership of the artefacts. You’ll probably be asked to explain what you were doing down there, retrieving items from a known wreck.’

Bram sighed. ‘We expected as much. But what were we supposed to do, Feine? Just leave those things down there? Let the storm wash them away?’ His voice had risen an octave, fuelled by the force of his words.

There were no easy answers to his questions. They echoed 28the complex relationship between world heritage committees and amateur collectors that had been going on since the dawn of time. In Texel, scavenging had always been a way of life. Ships broken apart by storms spilled their cargo into the sea and the tides washed their goods ashore where eager locals waited to take their pick of the spoils. Sometimes rare and useful items materialised. One year, a midnight squall sank a tanker carrying luxury fur coats. Everyone showed up at church the next day dressed like glamorous movie stars. Locals had a name for this unique beachcombing tradition. They called it jutter: what the sea gives, the finder keeps. But even a remote place like Texel couldn’t escape regulation altogether. In 2007, the Netherlands had committed to an internationally binding agreement designed to protect sites of marine archaeological significance. If you found something valuable on Texel, you were supposed to report it to the Strandvonderij – the official beachcombing board – who would take possession of the goods, if they were valuable, and decide whether a finder’s fee should be paid. Penalties for violating the agreement ranged from a slap on the wrist to extensive jail time. I tried to imagine Bram sharing a cell with hardened criminals, trading heroic diving adventures for tales of bikie vengeance and corporate greed. The image refused to stick.

‘We’ll sort it out when I get there,’ I promised him.

2

An hour later, I was back home and packing when Marieke burst in. ‘I’ve got tickets to a play tonight at the Sydney Theatre Company! Margaret was supposed to come along but her daughter’s sick so she’s watching the grandkids. I thought you might like to join me instead.’

Her gaze swept the room, taking in my documentation folders and the camera lenses cushioned in their fabric packing cubes. The wardrobe door stood ajar, revealing the gaps where clothes once hung. In the open duffle bag at my feet, a cross-section of jeans and jumpers was layered between the delicate paintbrushes and fragile fibre-optic lights to protect them from damage during the flight.

Marieke’s smile faded.

‘You’re leaving,’ she said, sinking onto the bed. She was wearing a tight, sleeveless shift dress patterned with purple hyacinths which showed off her tiny waist. A green sweater tied around her shoulders softened the sharp protrusion of collarbones.

‘What about the university? I thought they were expecting you to stay on until the book’s finished.’ 30

‘They are,’ I said. ‘But I’ve been offered an opportunity I can’t really refuse.’ I plucked a pair of copper pliers off a shelf, dropped them into a ziplock bag. ‘Bram Lange called earlier. You remember Bram? He wants me to visit him on Texel. I agreed to go.’

Marieke pressed a palm against her thin chest.

‘At last! What changed your mind?’

I told her briefly about Bram’s phone call and the shipwrecked items. I didn’t elaborate on the specifics of why Bram and his friends had been diving. If Marieke discovered there might be legal trouble looming on the horizon, she’d only come up with some unhelpful suggestion about putting things back where they belonged.

‘So you understand why I have to go,’ I concluded. ‘I’ll still be working on the book. In fact, if everything goes to plan, I might be able to use the research on the dress to write the final chapter.’

It was the first time all morning I’d let myself say those words aloud and, as soon as they were out, I knew they were true. I had the strangest sense of peering down through time, as though I was gazing into the ocean, trying to puzzle out sinuous patterns carved in sand. I wanted the dress for myself. Not to wear – I would never dream of committing such a sin – but simply to hold it and smell it, to experience first-hand its craftsmanship, its perfections as well as its flaws. There was something seductive about the way the silk fabric flowed, as if the dress, even on land, remembered an earlier version of itself. As if it were more fish than fabric. It would be the perfect example to support my argument that women’s historical clothing was just 31as worthy of scholarship as men’s. Women’s dresses were less likely to survive because they laboured harder, making do with what they had, altering or selling their gowns to compensate for disasters like the death of a protective male figure, a father or husband. They lived their lives at the mercy of other people’s whims. This dress was a survivor and I had the spookiest premonition that its owner had been, too.

Marieke could not possibly understand.

I went and sat beside her on the bed and held her hand. Up close, I could see the deep grooves her thick makeup hadn’t been able to mask, the ropey tendons in her slender neck. Although she was barely sixty, she looked much older. I’d always assumed this was due to the psychological effects of having to raise a child not her own. She’d spent years trying to convince my mother to uproot our family and join her in Australia, but she had been wasting her breath. My parents would never have moved away from Texel. They were like the island, entrenched in their ways, shaped by winds and tides that had blown into existence long before I was born.

‘It’s good you’re going back,’ she said, quietly. ‘It might bring you some closure. You know your parents loved you very much. They didn’t always show it, but they did. They only wanted what was best for you. Your mother always said your favourite time of the day was dusk because that was when she’d take you down to the beach to look for shoes. You were obsessed with shoes! They used to wash up quite regularly, especially after a storm, but somehow you always found left shoes, never right ones. You’d beg her to take you, even when it was still storming outside and she 32always let you convince her. She was soft-hearted like that.’

I stayed silent. There was no point arguing that, by the time my parents passed away, I was a stubborn sixteen-year-old who had long ago given up relying on them for either comfort or entertainment. I assumed the story about the shoes had come to Marieke via the long-distance phone calls my mother took at the same time each week at our kitchen table. Crouched on the other side of the door, I listened to Marieke espouse the wonderful freedoms of her new life in Australia, enamoured with the vision she painted of summer days and shiny, freckled faces, of the Opera House sails like shards of broken porcelain, gleaming against a Delft-blue harbour. I tried to convince my parents to let me visit but they refused to let me travel alone. Maybe they were afraid that I’d fall in love with the world beyond the island’s borders. My aunt had returned to Texel just once when I was born, staying only long enough to hand over a christening gift before driving back to Schiphol Airport and taking the first available flight back to Australia. She told me years later that people had treated her differently after she left Texel. It made her feel uncomfortable, as if two versions of her existed, sharing the same body, but neither one was whole.

‘Do you remember the lullaby?’ she said now.

‘No,’ I said, flatly.

I sighed. That damned lullaby. We’d been sparring over it for years, dancing around each other like boxers looking for our opponent’s weaknesses. The argument had gone on for so long, I could barely remember how it had started.

Marieke cleared her throat. I could tell she was getting worked up, assembling her reasons, laying strong defences 33in anticipation of my inevitable scorn.

‘It started with a wooden shoe,’ she sang, in a wobbly, off-key voice.

‘Okay,’ I said.

She waited for me to say more and when I didn’t, continued. ‘They sailed off, into the night, on a river of crystal light, into a sea of dew. “Where are you going?” the old moon asked. “To fish for herring,” replied the three. “Nets of silver and gold have we.” The old moon laughed and sang a song as they rocked in the wooden shoe, and the wind that sped them along that night ruffled the waves of dew. All night they threw the nets, to the stars in the twinkling foam, then down from the skies sailed the wooden shoe, bringing the little fishermen home: Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.’

She sang the last line again, softer this time, trailing off into uncomfortable silence.

‘That was it,’ she said, wiping her damp eyes. ‘Your parents were Wynken and Blynken and you were Nod, the one who was always falling asleep. I can’t believe you don’t remember. It’s simply not possible, Josefeine. How can you hear something every day of your life and not remember it?’

She was guilting me, expecting me to respond the way I always did. Truth be told, I didn’t remember the lullaby. Maybe that was why I could refute her claims with such absolute conviction. There was a hollow emptiness where that memory should have been. If my parents had sung me the same lullaby every night without fail before I went to bed, wouldn’t I have remembered it? According to Marieke, they’d stood outside my room crooning the song together, 34my father’s booming tenor balanced by my mother’s soft contralto. They’d met at an audition for the church choir when they were seventeen and married a few years later. I don’t know when, precisely, things had soured, whether the rift occurred soon after the wedding or if some other event was the catalyst for the marital disruption. Had my birth been an accident or had they hoped it would save their foundering marriage? If so, the experiment was a failure.

Marieke insisted my recollections of that time were wrong, that I deliberately skipped over all the good things about my parents. She claimed we’d once been inseparable, like the three fishermen from the lullaby, sailing our shoe into the sky to catch falling stars. I didn’t remember it that way. Even as a child, I knew I was different, a changeling belonging to another family. I wished I could give Marieke what she wanted. It would be so easy to lie and say I remembered only kindness and warmth, safety and protection. But it would not be true. And the truth was important to me. It was what drove me to uncover the stories woven into the clothing I was charged with preserving. Human history and textiles were inextricably linked; one could not exist without the other.

‘It doesn’t matter now.’ Standing up, I jammed a pair of archival gloves into the suitcase, hoping she’d take the hint and leave me to finish packing. By some extraordinary stroke of luck, I’d managed to nab one of the last flights out of Sydney today. The plane didn’t board till six, but I wanted to get there early so I could sit in the lounge and write out the contingency plan I was formulating – an emergency response to counteract damage inflicted on the improperly handled artefacts. I needed to try contacting Liam again, too. His 35mobile had gone straight to voicemail. He was probably up to his elbows in lab work or stuck in some dusty archive.

Marieke sighed. ‘I always thought Hilde would run off with you to the mainland,’ she said. ‘But she stayed on the island, against all the odds.’

I crossed the hallway to the bathroom to retrieve my toothbrush, ‘Maybe you didn’t know her as well as you thought.’

‘It wasn’t that. She met someone. They were together for years.’

I froze. ‘Like … a boyfriend?’

I couldn’t say lover. It didn’t gel with the image I had retained of my mother in her stiff blouse and humble cotton skirt. At the same time, Marieke’s declaration that she’d been carrying on an affair did not altogether shock me as it probably ought to have done. I’d known for years about my parents’ extramarital dalliances. They loved to fight about – not the affairs themselves but the way my father went about it. He was often careless, forgetting to hide hotel and restaurant receipts or encouraging strange women to leave cryptic messages on our answering machine. One night, a particularly bold paramour showed up at the house. She parked her car, with its mainland numberplates, in the middle of the drive, the idling engine louder than a speedboat. From my bedroom window, I watched my mother cross the lawn and peer into the driver’s side. I heard her knuckles rap the glass, the retort echoing like a gunshot through the cold night air. When the car drove off, I climbed back into bed and tried to sleep. But it was impossible to block out my parents’ raised voices. When I came downstairs the next day, they 36were eating breakfast as if nothing had happened. Ignoring me, my mother handed my father the milk and asked what time he would be home so they could take their evening walk across the dunes. My father said he had some business to take care of in Horntje but he planned to be back no later than five. Everything was so calm and placid; if I hadn’t caught the glare that passed between them, I might have convinced myself I dreamed the whole thing. I forgot all about it, although things between them grew increasingly cold.

They died a year later.

At the funeral, I half-expected a few strangers to come forward and lay claim to their affections. Nobody did. If my mother’s suitor was in attendance, he was indistinguishable from the neighbours and colleagues who crowded into the packed churchyard, stamping their feet to shake the damp clods off their boots, hugging themselves to ward off the winter chill. In books, revelations always take place at weddings and funerals. Jane Eyre discovers Rochester’s dark secret, Hamlet is driven mad with grief over Ophelia’s suicide, Miss Havisham stops the clocks at twenty minutes to nine and spends the rest of her days eating rotten wedding cake and corrupting impressionable young minds. In real life, people take their secrets with them when they die.

I walked back into the bedroom and knelt beside Marieke.

‘Who was he?’

‘His first name was Gerrit. I don’t know his surname. They met at a café in town, but he worked at the ranger station.’

‘He was a scientist, then.’

Marieke shrugged. ‘Maybe. Your mother never said.’ 37

I tried to recall the faces of my mother’s friends. Had this Gerrit been the reason for my mother’s increasing distraction in the last few months of her life. She’d been even more closed off than usual. I was living almost permanently at Bram’s, returning to my parents’ house only on weekends.

Bram’s mother Carlijn had taken me under her wing. With four boys and one husband to care for, I think she saw my presence as a way of counterbalancing the male energy within the household. She kept a bed made up for me in her craft room, her fortress of femininity – floral armchairs and chenille quilts and pressed flowers blooming in gilded frames. She loved to sit with me and talk about what I planned to do once I graduated high school. One summer, she taught me how to sew but, although I enjoyed the practice, I abandoned it quickly in favour of the much more thrilling hobby of scuba diving.

On land, Bram’s father, Tomas, seemed awkward and reserved, but he transformed in the water. He was warm and effusive, eager to share the diving skills he’d spent a lifetime perfecting. Although he was careful never to endanger us, he consistently pushed us beyond our comfort zones, taking us to dive sites that even more experienced divers might have found challenging. We returned home happy but exhausted, eagerly anticipating the hot chocolate Bram’s mother always had waiting for us. I doubt my own mother even noticed what I was up to. When I’d mentioned to her, the day before that ill-fated trip to Saeftinghe, that I planned to stay at Bram’s so we could get up early to go diving, she blinked as if I were a stranger or someone whose face she recognised but whose name was now forgotten. She’d been fiddling with her wedding ring, twisting it this way and that, turning it so the metal caught the light from the kitchen 38windows and refracted it into a thousand tiny rainbows.

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘Be careful.’

The lukewarm warning irritated me even more than the compulsive fidgeting with the ring. I remember shouting at her, accusing her of parental negligence (I would not, under normal circumstances, have chosen that phrase, but I’d overheard Carlijn say it and I liked the way it sounded, the irrefutable recrimination it implied). My mother only stared at me for a long moment, looking sad, before turning away.

My thoughts returned to the present at the sound of Marieke’s voice. ‘Gerrit wasn’t from Texel, originally,’ she said. ‘He was a southerner, I think. Somewhere near Middleburg.’

I ran a damp palm along my thigh. ‘Why didn’t you tell me before?’

‘You never asked. Besides, I wasn’t sure it was my place. But since you’re going back, I thought it best to warn you. If he’s still there, you’ll probably run into him. Texel isn’t a big place. When are you planning on coming back to Sydney?’

It was my turn to shrug. ‘I’ll stay as long as I’m needed. Once the items are stabilised, there’ll be some diplomatic stuff to negotiate with the Dutch government. The media will probably be involved, which will require some careful handling.’

She looked suddenly worried. ‘I’m glad you’re going. But what if there’s an accident? A break-in?’

Her voice was edged with panic, but I was wise to her ways. Her anxiety was mostly performative – an unsubtle device designed to trap me into staying home. There was no malice attached to her behaviour. She couldn’t help herself.

‘You’ll be fine,’ I said, tryingto make my voice as soothing as possible. ‘Call a friend, if you’re worried. 39Call Margaret; she’s supposed to be your best friend. You managed on your own for years when I lived in London.’

‘That’s because you were only ever a phone call away. The reception’s probably terrible on Texel. It took weeks sometimes for your mother to reply to my emails.’

‘She was probably too busy flirting with Gerrit,’ I said. ‘I don’t understand why two people who were clearly miser-able together didn’t just get divorced.’

Marieke looked pained. ‘It was a different time. And there was you …’ She touched my arm gently and I didn’t react, even though my first instinct was to pull away. ‘Isn’t it time you let go of all those old hurts and just listened to me for once?’

Her gaze was pleading. I glanced away from her towards the bookshelves filled with beach-worn paperbacks, their spines bowed, their covers bleached from prolonged exposure to the noonday sun. Those books – mostly historical romances – had been my companions when I first arrived in Sydney. Although I’d loved the stories themselves, I often found myself perusing the badly Photoshopped images of medieval knights and coquettish Victorian mistresses on the covers, searching for hidden meanings about the lives of the characters between the pages. Only later did I realise it was the clothes themselves I found so irresistibly alluring. Clothing held the key to thousands of years of human history, everyone from anointed kings and queens to humble washerwomen and midwives. It was my duty to follow the clues, wherever they led.

3

Anna Amsterdam, 1651

On the last day of her old life, Anna Tesseltje wakes to find the water in the washstand has frozen solid. She uses a knife to jam the blade against the porcelain until the ice breaks apart, the cracked halves glisten like oceans trapped inside a storm glass. After dropping to her knees to pray, she dresses quickly, eager to fashion a barrier between her skin and the frigid air, even if that obstacle is only the addition of a cloak. After a wet autumn, winter has finally settled over Amsterdam, bringing frost and wild winds and stinging sleet. She has learned to sleep in whatever clothing she can find, shivering as cold seeps through the windowpane. But she refuses to sleep in the cloak. The cloth reeks of the bleach her sister Lijsbeth rubbed into the worst of the stains as well as some lingering, unidentified malodour – the sweetness of rot. The sleeves hang past Anna’s fingers. She folds them back, trying to ignore the spectre of the cloak’s former inhabitant. The dame at the second-hand clothing market swore that the owner sold it to her on her way to her new situation to work as a maid at a grand house on the Golden Bend. She suggested the cloak would bring Anna luck, too. You can’t put a price on 41luck, Anna knew she should quibble over the cost. If Lijsbeth had been with her, she would have. Instead, she handed over three stuivers and prayed that, whatever the owner’s real fate, she had not died of the plague.

Slipping the protective pattens over her thin-soled shoes, she tightens the leather straps and ties a freshly starched cap over her hair. There. She is ready, except for her face and hands. She runs a finger along the hard spine of half a frozen slab. Her once-white hands are now permanently stained with ashes, the nails cracked from all the lye Lijsbeth insists on pouring into the copper pans they use to launder other people’s collars. Their friends have been kind, under the circumstances. There is always work for them. Not the kind of labour Anna once imagined, but what choice does she have? At least Cornelis de Witt, the successful engraver who lives on the Kalverstraat, doesn’t look down on her when she arrives at his door clutching a bucket under one arm and a basket under the other. One of the city’s favoured artisans, he once offered to tutor her – to show her how he made the engravings in their metal frames come alive, the shadowed planes of a woman’s face, the caulked ceilings of a church. It would be a leisurely distraction, something to fill in the time before her inevitable engagement. It wasn’t hard to convince her father, Lodewijk, to give his permission. Lijsbeth would need to be married first and they had not even begun entertaining suitors. Then Lodewijk had his first bad spell, the one that led to his rapid decline. Now her father is gone and, each week, instead of following Cornelis de Witt into his workshop, Anna follows his maid into the washroom 42to collect the household’s soiled nightshirts and stained collars. Sometimes, as she’s brushing down his shirts, a fine layer of copper shavings sifts like grains of sand onto the tiles. Sometimes, she shuts her eyes and imagines she is standing on a beach, watching ships battle a raging storm.