7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

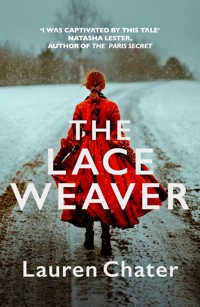

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

1941, Estonia. As Stalin's brutal Red Army crushes everything in its path, Katarina Rebane is desperate to protect her grandmother's precious legacy: the weaving of gossamer-fine shawls and the intricate lace patterns holding stories passed down through generations. In Moscow, Lydia Volkova is suffocating in a prison of privilege, yearning for freedom and hoping to rediscover her beloved mother's Baltic heritage. As the battle for their homeland intensifies, these two women are caught in a fight for life, liberty and love.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 625

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

3

THE LACE WEAVER

LAUREN CHATER

For the knitters of Estonia, wherever they are scattered

Each lace shawl begins and ends the same way – with a circle. Just like the stories we tell to keep ourselves warm. Everything is connected with a thread as fine as gossamer, each life affected by what has come before it and what will come after.

Sometimes a shawl is not just a shawl.

It is a voice, a force, a way of remembering. And every shawl we have made is precious, delicate enough to pass through a shining gold wedding ring.

This is our story.

Contents

Prologue

Elina December 1939

They say Estonia has five seasons.

Bitter winter. Pale spring. Autumn, when the forests are carpeted with mushrooms. Summer, with its blue cloudless skies and rich harvest of fruit. Lastly, my favourite: the thaw. That month of watery deluge when the ice floes break up to flood the land. In those weeks, it is impossible to get from place to place in the forest without a canoe or bog shoes to skim the marsh. The tide makes food scarce. One learns to get by on what exists in the pantry: lingonberry, gooseberry, juniper jam spread on thick slices of must leib – the black bread so prized by our people that a loaf, clumsily spilt, must be kissed to restore favour.

The pantry grows barer as the flood levels rise. The damp creeps into everything. And yet, I have always loved it. The isolation. I know that my granddaughter, Kati, feels the same. Forced inside, with the animals penned safely away and the outside chores impossible to complete, there is more time to be spared for the knitting of lacy shawls.

It is almost like winter, when the days are so dark the sun struggles to shine in the sky for an hour or two before fading away; but the thaw has none of winter’s cruel bite. Even now, closeted in my daughter’s house with the fire burning nearby, my hands are too stiff to take up the needles. The best I can do is hold the wool between arthritic fingers and let the spinning wheel do the work. Spinning wool is all I can be trusted with now, a job given to the infirm or the very old, and since I am both, this seems to be my fate.

The treadle beats softly on the floorboards in time with my heart.

What a pity I will not be here to see the thaw arrive this spring.

‘Grandmother?’

I look up. Kati is frowning, brows drawn down over eyes which are the crisp yellow-green of windfall apples. The knitting needles are held loosely in her hands, the wool a thin curtain of lace between them. I find a moment to be satisfied, to be proud, before her expression makes me frown in return.

What were we speaking of?

It’s so hard for me to follow a thought, a memory, these days. I’m never certain where it starts or where it will end. It might begin with the National Awakening; with the writer Carl Robert Jacobson and his rival Jakob Hurt, that collector of tales who set out in 1872 to record and preserve Estonia’s folk history. I might move on to the expulsion of the Baltic German nobles from their lands in the 1890s and then to the declaration of Estonia’s independence in 1918, the war with the Russians that followed, the victory and years of peace since. And of course there is my own history, less solid perhaps, the dates open to interpretation. A childhood in Haapsalu, a little seaside town on Estonia’s western coast. Warm days on the promenade sitting knee to knee with Mama, knitting shawls to sell to the tourists who poured in by ship or train beguiled by the promises of the local mud’s restorative properties. Folk songs at choir practice. Tales by the fireside. Dances at the local hall, where I met the man I would marry; the man who would convince me to trade the narrow streets and brightly coloured timber houses of my youth for a farmer’s life among apple orchards at the edge of the university city of Tartu.

‘You were talking about the War of Independence,’ my granddaughter prompts.

‘I was?’

‘Yes.’ A pause while she tucks away wisps of fair hair which have worked their way loose from her plaits. ‘And about Grandfather.’ Picking up her needles, she shakes them. The yarn is coiled in her lap, starkly white against the dark blue wool of her skirt. I recognise the skirt as a discard from her cousin Etti. Marta has lengthened it by adding a panel at the waist, so the hemline falls to brush Kati’s shins. The result is not fashionable. I may not see well, but it’s hard to miss the way girls get about in Tartu these days in skirts which barely graze the knees, displaying lengths of calf as smooth as buttermilk, even in winter. I don’t fancy Kati minds so much. Hasn’t she, after all, tasted the very thing those girls crave; the sweetness of a friendship which has blossomed into love?

I knew at once, of course. She didn’t even have to tell me. One look at the flush in her cheeks when she says her sweetheart’s name brings memories of my own courtship flooding back. The sweet smell of floor wax mixed with kerosene from oil lamps strung up around the hall. Eduard’s palm resting against my back as he guided me through the polka steps.

I let my foot pause upon the treadle. The yarn slackens in my hand. From outside the window comes the rhythmic thump of snow falling from the eaves. I let its meter dictate my words, thinking of my husband’s fate. It’s a story I’ve not told often and I wonder at my choosing it. ‘He was part of the Tartumaa Partisan Battalion.’ I pause. ‘He was killed in the Battle of Paju.’

We sit in silence. There is pain in talking about such things, but it will not be long, I suppose, before I join him. The ache in my bones is worse now. At times I find it difficult to move from my bed. On the coldest days, not even the tempting smell of Marta’s rye bread can shift me. Of course, I don’t complain. Estonian women are not given to moaning about their lot. My own mother was up and scrubbing linen mere hours after I was born; a story she used to tell with a shrug of her broad shoulders, as if such feats of female accomplishment were not worthy of admiration. They were simply facts, as certain as the seasons, as unchanging as the slaughter of sheep in spring or the harvest of hay in June.

Sometimes, it is as if I can already sense my husband; I might turn and find him sitting in his favourite chair, watching me with eyes the deep mirror blue of the Haapsalu tide. At such times, I am seized by questions. Am I ready to let go? My family still needs me. I still have so much to say. Who else will listen to the knowledge I have to pass on? Who else but Kati will care to remember that the finest yarn for knitting can be found on the back of a lamb in the soft depression at the base of the neck, or that the best needles are lilac wood, oiled with sheep’s fleece? And what of war? For the past months, there has been restlessness in the town. Rumours fly about like wayward flags snapping in a cold breeze. There are military demonstrations on the Russian border that suggest a time may soon come when the fragile peace in our land will be broken. I have seen the invasion in my dreams a dozen times; heard the rumble of tanks, tasted the gunpowder on the air. How will my family survive, my friends in the knitting circle? It will be as things were before the War of Independence. Estonian language outlawed. Old tales reinterpreted until they reflect a Russian taste. Who will keep our stories? Who will guard our history until it is safe to tell?

I sense Kati watching me, although she pretends to concentrate on slipping her stitches onto the next row. Her fingers dance around the needles, barely touching the fine yarn. She holds her hands slightly bent, thumbs flat, the way I taught her. In the lace already knitted I see my favourite shape leap out: wolf’s paw, a pattern I designed many years ago as a child, long before we moved into this farmhouse nestled among the firs.

Why a wolf?

In Haapsalu, we did not see wolves. The coastal air was too laden with salt for their taste. Such creatures prefer the scent of balsam. It was foxes who came to our doors and windows. Foxes who rummaged in the kitchen peelings for scraps and riled up the chickens, melting away through broken fence palings when we shouted at them from the window.

It was not foxes I dreamt of as a girl, though. It was wolves, travelling fleet-footed through the snow, dancing across the marshes, skirting farmhouses on their way into the deep forest. I’ve always wanted to see one but it has never occurred. Perhaps I knitted my desire into my work. I wonder if Kati, too, dreams of wolves or if she, in reverse, dreams of the sea. She travelled outside Tartu but once as a child and so can only imagine Haapsalu from my descriptions – the sweeping promenade, the lap of the tide, the narrow streets which all lead down to the sea.

It comes as if I have conjured it; a howl that pervades the room, a lone animal cry from the darkness beyond the window. I’m not surprised. Winter is wolf season. Best check the bolts and count the ewes, my husband would say. Yet I can’t help but think that the sound is symbolic, a portent meant for my ears.

Kati begins to rise to her feet, unnerved, but I shush her with a gesture and take up the yarn again. The wool unspools in my hands, the fibres separating briefly before the spindle draws them in, twisting them together in a soft rope. ‘When I’m gone,’ I tell her, ‘I will send you a sign. You will know it’s me. I will wear the pelt of a wolf.’

She makes a small noise of disbelief.

‘There will be no need to fear,’ I continue. ‘I will travel alone. Everyone knows a lone wolf is kind.’

‘You’re dreaming,’ she says softly. After a moment, her needles begin to click again. ‘You’re tired.’

I smile to myself. Let her think she is right.

In my mind, I turn away from my husband’s ghost. His face is full of sorrow, and for that I am contrite. He reaches out a hand to touch me, but his fingers find only mist. One day, I tell him, we will be together again. But not now. When he begins to fade, his eyes are last to disappear.

‘Grandmother,’ I hear Kati say again, but it is as if we are speaking from opposite ends of the forest. The trees form a barrier between us. The air is sharp with sap and silt. My limbs no longer ache. They pound the ground and blood thrums in my veins. Old songs and stories cry out from each twig and leaf. My breath is a plume of white mist.

It would be easy to lose myself in the intoxicating sense of freedom, but I hear Kati’s cries drawing me back. A weight settles over me like a mantle of snow. There are shadows up ahead. Horrors nobody else has foreseen.

I have made a promise I intend to keep.

Wolf’s Paw

Katarina June 1941

I saw my wolf again tonight.

She appeared at dusk, a shadow among shadows, slipping down the slopes on spindly legs to the edge of the forest where the trees begin to thin. The dying sun made a golden silhouette of her pointed ears and muscled flanks, her long whiskered snout.

I say ‘my’ but she no more belongs to me than does the wind that rattles through the ash trees or the soggy fields surrounding our house where people buried their belongings in haste before they fled the Soviet invasion. Tarnished cutlery, a child’s soiled leather shoes, a bound journal of spotty, dog-eared photographs. The churned earth spits up their treasures after a heavy rain as if to say, You see? Nothing stays buried forever.

In the room behind, Papa tapped his pipe against his hand, a familiar thwack-thwack.

Mama clattered the bowls into place on the table, humming a song beneath her breath. The rhythm of it rose and fell: an old folk song about the baking of bread. I knew the words. I longed to hear them. But I knew also that Mama would not sing them aloud.

I pressed my ribs against the sill, searching in the semi-darkness with my hand until I found the hard edge of the planter box on the other side where our herbs were kept, far away from the greedy maws of sheep. The sprigs of dill tickled my palm.

The soup was spluttering on the stove. Sprinkling the herbs over the broth, I let my mind wander to the sheep, already penned in the barn below us, the ewes separated from the ram by a thin timber wall.

Should I warn Papa about the wolf? Some said that to slaughter a wolf was to bring misfortune down upon your herd. There were better ways to deal with such things; smearing birch tar upon the sheep’s fleece to mask its scent. Scattering a sacrifice of bones into the forest when the first frosts came. In my great-grandparents’ time, perhaps a spell. My grandfather once told me of a wolf that had wandered so far from the forest that he became lost in the village, and my great-grandfather along with the other local men had driven him back, arms raised, calling at him: ‘Be gone, old grey streak eye, billygoat of the forest! Go back to the bogs, go rove in forests, scratch the trees, tear at stones.’

Yet none of those men had dared raise his gun at the creature for fear of the bad luck it might bring.

Throwing caution to the wind, I glanced back at the window and the gathering darkness filling the yard.

My wolf was gone.

I breathed again. Despite his reluctance, there was no doubt Papa would be obliged to take up his gun. While other farms were forced to hand over all their goods and livestock to the state when the Soviets first arrived last year, we were, by some fortune, permitted to stay. As long as the sheep were kept safe and the apple trees in our orchards continued to bear fruit, we were allowed to continue living as if our lives were not pieces on a chessboard, able to be scattered at will by the local Partorg, the Communist Party Organiser, whose job it was to ensure that the state’s property was in good hands. My father often said that the sheep were our angels and I their guardian.

If I was of good humour – if the weather had been mild, if I found a moment to add some stitches to my shawls and there was the prospect of meat or tender vegetables to line my belly, I would grit my teeth in a smile. But most of the time, I didn’t. Each bleat and baa echoing up through the floorboards was a reminder of how the stupid creatures were fed the best of each harvest, while we boiled chicken bones until they were bleached of every marrow scrap. Each snuffle and scrape of their horns, a reminder that they were worth more than we were. The only thing they were good for, the only thing that made me bless their ‘angel’ heads, was the fleece we sheared from their backs each spring. Sometimes in my dreams I saw blankets of fleece laid out upon the threshing-room floor, ready to be sorted and fed through the spindle to create the yarn we send to factories, after I have saved some for the knitting of shawls. In dreams, there was an endless supply, a bounty; as soon as the wool was spun, more fleece appeared to take its place. Even asleep, I was aware of this blessing. It meant our knitting circle would never falter. It meant my promise to my grandmother would not be broken.

Mama cleared her throat. ‘Katarina?’

‘What is it?’

‘Your sleeve is in the soup.’

I cursed and stepped back from the pot, flicking droplets of broth onto the floor. Mama sighed and nudged me away. ‘Here. Let me serve. You’ve got your head in the clouds again. What were you thinking of?’

She took the soup pot off the stove, sliding it onto the rough-hewn table that bore the scars of the childhood I shared with my older brother Jakob, who now lived ten miles away at the university dormitories in Tartu. Here was the deep groove where my sewing scissors had slipped. Here were the runes where my pencil had worn through my exercise books and left an impression upon the grain. I ran my finger along a chip in the timber. Literature and history. Subjects for which I would drag myself across snowy fields and the bog marshes to our little parish school, eager to learn more while Jakob dawdled behind, carving symbols into the trees with his knife. That was before everything changed. Before Grandmother passed, before the Russians marched in to seize the lands, before Oskar disappeared. Before Papa put me in charge of minding the sheep, and my dreams of studying stories and folklore at the university were extinguished.

I heard Papa’s voice, as clear as if he had spoken, although his pipe was clamped between his lips now and he was staring silently at the soup my mother had set before him. The words I remembered were an exchange between my parents from years ago, overheard one night as I sat up late reading.

‘You cannot allow them both to continue their schooling, Erich,’ my mother said. ‘We can’t manage the farm alone.’

The bed squeaked as Papa turned over. ‘There’ll be workers in June to help.’

A pause. I imagined my mother frowning.

‘One of them may go and one of them may stay to help,’ he said. ‘We can only afford to send one to the university anyway.’

How naïve I had been to think that one would be me.

The oak table was warm beneath my hand, as if it too could remember a time when life seemed full of potential. I slid into my chair and took a quick slurp of broth, forgetting to cool it first. The spoon clattered to the table as tears stung my eyes. Mama clucked under her tongue and thrust a cup of water before me. I gulped at the cool liquid until the burning in my throat eased.

Mama shook her head. ‘Really, Kati. You are nineteen. This daydreaming has to stop.’

She glanced across at my father, who slurped at his soup but did not look up.

‘Erich?’ my mother prompted. ‘Don’t you agree?’

‘Perhaps,’ he said. He set down his spoon. ‘Or perhaps it was Kati’s polite way of saying that the broth is not very good.’

Mama looked from me to Papa, lost for words. He picked up his spoon again and took a long, lazy slurp.

Finally, she said, ‘Well, it would not be so bad, Erich, if I had something other than old chicken bones and rancid turnips to cook with.’

Papa glanced at me and wiggled his thick eyebrows. Suddenly, the whole situation seemed humorous.

‘I just so happen to like turnips,’ he said. ‘But this tastes less like fresh turnips. More like water into which a turnip has been dangled and then snatched away.’

Mama’s shoulders relaxed. She smoothed back her hair and adjusted the shawl around her neck which had slipped a little as she moved about serving the food. The snowy white lace made even her threadbare dress, with its faded pattern of roses, seem almost elegant. Although she was thinner than last year, she was still beautiful with high cheekbones and an elegant nose which both Jakob and I had not inherited. We both had the Rebane nose; short and wide, with a sloped tip.

‘You are welcome to suggest something better, Erich,’ Mama said, her pointed chin lifted.

‘Perhaps tomorrow we could have turnip pie,’ he said, the corners of his mouth creasing. ‘And with it, a turnip salad?’

‘And … turnip ice cream,’ I supplied, my heart lifting.

‘Well,’ my mother conceded, ‘I could do better than turnip soup, if you would only allow me to buy a few of those black-market potatoes.’

‘Oh yes!’ I said, stirring my spoon round and round through the weak soup, allowing myself to dream, along with my mother. ‘Those fat, creamy potatoes … or thick, buttery carrots.’

It was the wrong thing to say.

Papa snatched up his spoon again, gripping it in his fist. ‘Put it out of your mind, both of you. I’ve told you; those items are banned. Do you want to go to prison? We can’t afford to be arrested.’

Arrested.

The word hung between us.

Below, the ewes bleated, the sound drifting up through the floorboards like laughter. Papa sipped his soup, but his smile was gone.

If Jakob were here, I thought, he would know what to do. He would tell a joke, a slightly inappropriate one that would make my mother exclaim, Jakob! and would make Papa’s lips curve in a secret, knowing smile. But I am not Jakob. I am Katarina, a girl considered not worth sending to the university to further her studies, a girl who must endure day after day of the same monotonous tasks, shackled to the responsibility of keeping a flock of guileless sheep safe from harm. A girl whose only pleasure comes from knitting and from remembering the stories her grandmother left behind.

Perhaps even Jakob could not make light of the way the Russians terrorised those of us who remained behind when the occupation started. There was nothing funny about the way our leaders had been arrested and parliament dissolved, or the seizing of radio stations so that the Russian occupiers could assure us all our government had been the enemy. There was nothing playful about the way their soldiers commandeered vehicles and houses, throwing Estonians and their children out of their homes and deporting anyone they suspected of holding ‘capitalist sympathies’. My grandmother would have wept to see Tartu now; all the lively cafés gone and Estonian businesses boarded up. Patrols of young Russian soldiers roaming the streets in packs, looking for any excuse to refer people to the NKVD Secret Police at the Grey House on Põder Street, the place where one could be tried and shot before their family even noticed they were gone.

This was the reality of our lives now. Everywhere I went and every action which took place outside the privacy of home was accompanied by an undercurrent of fear. Each stranger I spoke to could report me as a spy. Each knock at the door could be an agent with a warrant to search our house. There were no safe places left except the arms of my family and my private thoughts. There was no way of resisting except to stay alive and to fulfil the promise I had made my grandmother; to maintain our culture through the knitting circle, to keep sharing our stories and continue the tradition of making shawls.

I sighed and drained the last of my soup, stomach still tight with hunger, then I stood to help Mama clear away the things.

Papa shifted in his seat. He cleared his throat.

‘Katarina … I need to speak to you.’

I froze, the empty soup bowl suddenly heavy in my hand. ‘It’s not …’ I could not make my lips form my brother’s name.

‘No,’ my father said quickly. ‘Jakob is safe.’

Relief was instant. Demonstrations. Deportation. Death. It was hard not to let my mind wander to the worst, especially with Jakob staying away for months on end, avoiding trips home, spending all his time in the dorms with his friends. Mama had threatened to go to town herself but Papa dissuaded her.

‘Then who?’ I continued.

In my mind, I was flicking through the faces of the people I knew. Which one of them had been punished this time, or worse, had vanished without warning? Not Aunt Juudit, I prayed, thinking of her wide-set green eyes, so like Papa’s and my own. Not gentle Etti, her husband taken and killed at the hands of the Soviets while she remained, big with child, unable to push herself off the lounge unassisted. How could she run?

Papa, watching me, summoned up a weary smile. ‘Nobody has been hurt, Kati. Yet.’

I wanted to sink into my chair, but I continued to stand. My father had more to say. I could see him measuring the words carefully in his head, thinking of how best to frame them. His pipe was clutched in one hand, the embers turning to ash.

Whatever was coming, it was something he knew I wouldn’t want to hear.

‘Kati, the Partorg’s men were here earlier.’

I forced myself to remain standing. ‘What did they want?’

My father scratched at his whiskers. ‘I’m afraid there will be no wool for shawls this winter.’

I stared at him. ‘No wool?’

‘I’m sorry. The Partorg has increased our wool quota for the coming year. The only way we can meet it is to give up the fleece we use for your yarn.’

I blinked. ‘No wool,’ I repeated. I waited for the words to bring relief with them. Nobody was injured. Instead, an empty, hollow feeling opened up inside me.

No more wool meant no more shawls.

‘There must be a mistake.’ I glanced across at my mother, willing her to smile, to slap my father on the arm the way she had done earlier in that brief shining moment of camaraderie. But my mother’s face was pinched.

‘No mistake,’ Papa said. ‘I wrote the figures down myself.’ He reached into his pocket and drew out the small book in which he kept all the details of our farm. The tools, the position of the apple trees, the demarcations that divided our land. He had bought the book last year, when the Soviets first seized power.

‘We will not resist,’ Papa had warned us. ‘We will be model Soviets.’

Now the pages of that little book were black with soil and well thumbed, the green cover creased. My father flicked it open in the middle, holding the pages out for me to see.

I did not lean forward to confirm my loss. I couldn’t.

‘What about the reserve?’ I said, thinking fast, calculating how much wool was needed for one row of stitches, how much yarn could be stretched to piece together a shawl. ‘We still have the bales left over from last year.’

My father was shaking his head. ‘They already suspect us.’ He heaved a sigh. ‘They are questioning the sale of your shawls at the flea market. Claiming that what I’ve been handing over is too little.’

‘Ridiculous. We earned that money!’ It was hard for me to keep the righteous anger from my voice. Although there was a flea market in almost every village, and they were quite often raided, the Russians had not yet banned the sale of handicrafts, which were considered worthless, therefore less of a threat than foodstuffs and clothing, goods which were controlled and distributed by state-sanctioned factories. The Partorg had allowed us to continue operating our little market stall once a month provided most of the profits were handed over along with Papa’s quota of apples for the month. What we made was hardly enough to cover the cost of the wool. It certainly did not cover the time I spent dreaming up designs and the effort we all made to knit the shawls, but money had never been our motivation. When I stood at the stall, my head held high, and watched the Russian professors stop to admire the neat stitches in my shawls, I imagined a tiny bit of power kindling in my chest. When I took their roubles and placed them in the jar below the table, a warm feeling spread through my hand, knowing that we were, in a small way, defying the Russian government’s attempts to stamp out our past. I always smiled as I passed over the neatly-wrapped shawl and sent out a little wish as I watched the buyer’s departing back, hoping that the shawl would be cherished and admired, perhaps passed down through the family so that its link to Estonia was forever strengthened.

‘I know, Kati.’ My father sounded weary. ‘I know you did. And I was willing to overlook it. But they know us and they know the farm. Every last bit of it, every last blade of grass.’ He frowned at the little book. ‘Perhaps I should not have been so hasty in writing it all down.’

My mother patted his arm. ‘You are the reason we are still here, Erich. Without you, the farm would not have survived. We would not have survived. Kati understands, don’t you?’ She flicked a warning look at me. ‘They are just shawls. Just bits of cloth. Shawls are a luxury these days. Nobody can afford to buy them anyway – or sell them, it seems.’

I stared at her, but my mother shifted her gaze, still patting my father’s shoulder in a comforting manner. A slow burning heat spread across my skin. Just bits of cloth?

My grandmother had been right. Mama had never loved knitting the way we did. She was born of a generation where freedom cost dearly; her own father and brothers were killed trying to drive out the Red Army and the Baltic Germans during the War of Independence. We were but a tiny country, a stone cast between the Gulf of Finland and the vast landmass of Russia. Even with the aid of our Baltic neighbours, the Latvians and Lithuanians, we did not have enough people to defend our borders from attack. We’d been lucky to defeat the Red Army back in 1920 and, although many would not say so, it was likely that such a victory would never have taken place if the rest of Europe had not been preoccupied with their own struggles. At the mercy now of the great Soviet powers, how could Estonia hope to remain free? All we had was ourselves, our history, our stories of the land. Papa had told us when the Soviets arrived that our survival depended on our compliance. He could remember a time when resistance was met with the end of a bayonet. Better to sign away some of your rights than to lose your life, he had said. Better to stay and try to make it work than to flee to unknown shores, leaving behind your family and your friends, everything you had worked so hard to gain.

I tried to imagine what my life would be like without shawl-making. Sometimes it seemed as if shawl-making was all I had left. It was my lineage, my passion. It anchored me not only to the knitting circle but to my grandmother. Widely acknowledged as a master knitter, she had started the circle when she moved from Haapsalu, gathering women first to our little croft and when that became too small, convincing Aunt Juudit to host the group at her apartment in Tartu. I’d been accompanying her to their gatherings since I was five years old and had successfully knitted my first lace shawl; a miniature version of the pasque-flower design for Maimu, my doll. With endless patience, my grandmother had teased out the latent talents of her friends, restoring confidence when required or providing challenges whenever the knitter seemed ready to move on to a more difficult stitch. Since her passing, I had done my best to live up to the legacy she left behind. I missed her most when I had a question about how she achieved a particular effect in one of her prized lace shawls. How she was able to keep the tension in her yarn as she sewed on the lace nupps, the small lacy bobbles that told a buyer that a shawl had been sewn by hand. How she could join two pieces of lace as if they had always been one.

If she had not passed away, she would still be organising the production and sale of the shawls for the knitting circle. Instead, she had appointed me to distribute the yarn for carding and spinning, to assign the various designs to each woman depending on what I thought would sell.

Although it had not been easy to step into her shoes, I knew she would not wish the circle disbanded. How could we give up knitting now, at this crucial point in Estonia’s history, when the Soviets wanted to wipe our culture clean as if it never was? Even the usual forms of communications were forbidden now. Radios had been confiscated, type-writers banned. With no way to contact the outside world, the Soviets imagined we had no choice but to comply, that we would forget the glorious freedom of expressing ourselves. I could almost hear her voice, creaky with age, whispering encouragement into my ears. Every shawl we make will be laced with defiance. Every stitch will carry a message out into the world.

Now that would be lost too.

Bitterness churned within me. ‘We should have gone,’ I said, banging the bowls together. ‘We should have left here like the others while we still had a chance.’

‘Kati!’ My mother blinked hard. ‘Don’t say such things! What about Jakob?’

‘You could have called him back.’ I glared at her. ‘Where has it got us? We have done everything they asked and still, it’s not enough. What about Oskar? What happened to him? What happened to Imbi Mägi? To Aime?’ My parents were silent, but I noticed my mother’s eyes glimmer with sudden moisture. I snatched up Papa’s bowl, unwilling to relent, unable to hold back the flood of anger that had grown inside me since the Partorg’s men had first set foot on our property. ‘This year it’s wool. Next year it will be apples.’

I waited for them to argue, but nobody spoke.

‘Aunt Juudit will expect me tomorrow.’ Disappointment dulled my voice. ‘At least let me go and explain to the knitting circle in person.’

My father spread his hands on the table, gripping the edges with his thumbs. ‘Fine. But you will go there and tell them and come straight home. No dallying. No sitting around until dusk wagging your tongue.’

‘But—’

‘Enough!’ Papa slammed the book down on the table. ‘Kati, I’m not asking for your opinion. I’m telling you the way it is. Do you understand?’ His chair screeched as he scraped it back.

Words died in my throat and I lowered my gaze. Somebody, my grandmother perhaps, had dropped something hot on the floorboards some years before and the burn had penetrated the thick hardwood, leaving a charred, black ring to stain the varnish.

‘Kati? I am waiting for an answer.’

Although my cheeks burnt, I forced myself to nod.

‘Good.’

The wooden floor creaked beneath Papa’s feet as he moved away, lurching towards the worn couch where he would sit for the next half-hour, going over the inventory of the farm in his book, before exhaustion overcame him and he retired to the bedroom. I was left facing Mama, who could not meet my eyes. Instead, she grasped the remaining cutlery and turned away, hunching her back against me in disapproval.

Cutlery splashed and sank in the tepid grey suds that filled the sink. The only other sound came from the wind that sounded against the windows, rattling them in their panes.

Knock, knock.

The sound came again.

Knock, knock, knock.

A knife slipped from my mother’s hand and clattered to the floor.

‘Stay here.’ Papa’s voice was sharp. We listened to his feet pound down the stairs, the groan of the barn doors being opened. My heart bumped painfully against my ribs.

Muffled voices echoed in the stairwell below, then silence.

Moments later came the sound of footsteps, slowly ascending the staircase that led into the living space. Mama reached out and squeezed my hand, her palm unsteady.

When at last Papa emerged at the top of the stairs, a thin sheen dampened his pale skin and his eyes were drawn. It was the same look he had worn the night we heard the Soviets arriving, when the sound of tanks and shouts echoed across to us from the main road that ran alongside the farm, when the truth of the rumours flying around Tartu had finally hit home with staggering force.

I closed my hand around Mama’s, a child again, seeking a path out of the unending nightmare that was the Soviet occupation. Would it never come?

A figure stepped out from the shadows behind Papa. The golden lamplight streamed over his features so that he seemed to glow at the edges, a figure conjured from a dream. Hope and longing collided in my chest.

Oskar. He was back.

Apple Pattern

‘Oskar Mägi … Can it really be you?’

In the living room of our farmhouse, Mama dropped my hand and took a hesitant step forward, her gaze fixed on the visitor before us as if she expected him to disappear the moment she looked away. ‘I can’t quite believe it.’ Her voice was quiet, equal parts fear and joy. ‘I feel like I’m staring at a ghost.’

Oskar’s face remained impassive but he lifted his chin. ‘Ma ei ole kummitus,’ he said, in Estonian: not a ghost.

I heard my mother’s indrawn breath and knew that she too felt the fluttery strangeness of hearing our language spoken again. The long Uralic vowels, the rhythm like a song. Hearing it awakened an unexpected longing in me. We had spoken only Russian since the Soviets arrived, even at home; it was safer that way. It was only now I realised how much I had missed it. How bleak and empty the world seemed without the comfort of those familiar sounds.

‘It’s good to see you, Marta,’ he said, still in Estonian. The realisation that he refused to speak Russian made my skin tingle, made the memories flood back.

The light from the oil lamps glinted on his face. Half-hidden behind Mama, I was able to study him.

His face had lengthened, the angled cheekbones more pronounced, although we all looked thinner. He wore a uniform of mushroom brown in a style and texture I had not seen before. It was wool; I could tell from the way the material absorbed the light, muting it so that if he stepped away, into the shadows, he might disappear altogether. His hands were encased in gloves. Crimson yarn, woven through with a pattern of white winter berries.

Somewhere in my body, an invisible, familiar drum began to beat, its steady rhythm pulsing outwards until I could no longer hear the snuffling sheep below us, nor taste the greasy residue of my mother’s turnip broth. There was nothing else.

I put out a hand and gripped the back of the nearest chair. The oak beam was solid, but a loose chair leg wobbled beneath the weight and squeaked. The sound made Oskar turn his head.

‘Kati.’

Our gazes connected, and a wave of memory caught me up.

Burnt sugar. The mournful lowing of cows waiting to be milked. A band of golden sunlight illuminating the varnished floor. And blood.

I turned away as nausea filled my stomach.

Swallow. Breathe.

Oskar’s mouth twisted. He took a step towards me but Papa coughed and he froze.

‘The Russians say you killed your mother and sister.’ Papa’s voice was heavy.

My mother flinched and glanced away. I too, wanted to turn my head, but could not bring myself to do so in case Oskar thought I believed what the Russians said. In the awkward silence that stretched on, I heard again the voices of the soldiers in my mind when they came to see us the day of Imbi and Aime’s deaths. The harsh guttural sound of their words. Murderer. Outlaw. Criminal. I remembered their faces as they spun us their version of what had happened, telling us that Oskar must have killed his family after arguing with them about resisting the order to hand over all weapons. It was not so surprising, they’d said, considering his socialist sympathies. Some passing soldiers heard what was happening and chased after him, but it was too late; he had already run into the forest so they went back into Tartu to alert their superiors. Those socialists would kill their own grandmothers given half a chance, one soldier had told us. If anyone from town was caught helping him, they would be arrested and tried at once.

All through their speech, I had wrestled with my desire to shout that they were wrong, to defend Oskar’s innocence but Papa’s hand on my arm was firm and so I kept my own thoughts locked away. But in my heart I was grieving, not just for Imbi and Aime, but for Oskar, too. They had covered up their own crimes by pinning the murders on him. They might as well have shot him.

‘I didn’t kill them,’ Oskar said softly now. His gaze darted to Mama. ‘Please, Marta. You must believe me.’ Beneath the hard lines in his face, I caught a glimpse of the old Oskar, the one who had played Vikings and built castles with me in the rambling orchard beyond his house and walked me home each day after school. The boy who turned his face away at choir practice so the other children would not see how the music moved him. The boy who had endured the teasing of my brother and his friends without ever raising his fist in retaliation. The boy who always brought his mother the first sprays of wildflowers when they appeared in Spring and gave his sister half his roll at lunchtime to ensure she had enough to eat.

Mama could remember that boy too. Her eyes were wet with tears. She brushed them away. ‘Of course we believe you,’ she said softly, ignoring Papa’s warning look. ‘Erich and I discussed it, once the soldiers were gone. Poor Imbi. And little Aime. She was too young.’ Her eyes filled again. Averting her face, she scurried to the cabinet and snatched up a mug. Filling it with water, she thrust it into his hand.

‘Thank you,’ Oskar said. He looked down at the mug, as if surprised by this sudden kindness. ‘I heard that you found them, Erich,’ he said. ‘I’m sorry. I wish I could have done something to spare you the shock.’

Papa shook his head. ‘It wasn’t me, Oskar,’ he said. ‘It was Kati.’

Oskar’s eyes widened. ‘Kati? Is that true?’

I dropped my gaze, afraid to look up and see the suffering this news might cause him. It was hard enough to face the memories I had to endure alone.

It had been spring when I found them, warmer than the one we were now experiencing. The wildflowers had bloomed early. Their spiciness mingled with the green scent of the rain that had left the river swollen and washed the sky a clear, cloudless blue. As I’d trudged the forest track that led between Oskar’s house and our own, I had brushed my hands along the edges of the fir trees. Their trunks soared above my head. They had set down their roots long ago, before the first settlers arrived, when Estonia was just a belt of wild forest filled with beasts. That Estonia was the one of Vikings and of the sagas of Iceland, her coasts a harbour to shelter in on the way to hunting waters, her islands stepping stones among the tides. It was the Estonia of men with the strength of ten plough horses and women who foretold their own destiny in dreams.

In the quiet of the forest, it was possible to imagine not much had changed at all.

The scent of fir needles lifted into the air, engulfing me as I walked the track I knew as intimately as the pattern of my grandmother’s lace. There was no chance I would linger idly, enjoying the breeze as it wafted through the trees. Oskar was waiting.

I could picture him pacing the small porch that wrapped around the farmhouse, eager to escape his chores, perhaps rubbing his toe against a loose board, eyes searching the track. His mother too would be awaiting my arrival. She’d always been fond of me, but lately she had been nervous. The presence of the Russians in Tartu disturbed everyone. She would grab my arm when I arrived and pull me indoors, her worried expression clearing until her round face was again as smooth as the dough resting in its bowl in the sun.

The dozen apples in my knapsack jostled and bumped against the small of my back. Mama had sent them for Oskar’s mother, a gift. In exchange, Imbi would send back the berries that she and her daughter Aime had picked. Thinking of Aime always brought a smile to my face. Although there were six years between us, I’d known her so long I sometimes felt she was my little sister, too. Once during the autumn holidays, Oskar had fallen ill with the measles and Aime had come to stay with us. She shared my bed and risen early to help me prepare breakfast and unpen the sheep. Although she found knitting difficult because of the long hours of sitting, it was a pleasure for her to tramp into the forest to harvest fruit. She delighted in showing me how to peel back the moss to reveal a clutch of fenberries hidden beneath. Imbi had taught her which berries were safe to eat and which must be left behind. Cloudberries, small orbs of shiny copper with a lingering honey flavour, were the most prized, for each plant only grew one stalk.

‘You should make a cloudberry shawl,’ Aime had once advised, her eyes sparkling as she dropped one of the precious globes into my hand and tucked the rest away in a soft sack for her mother to preserve.

Imbi was the queen of preserves. My mouth was already watering in anticipation of the sweet seeded strawberries she soaked in elderflower wine and served with thick slices of malty brown bread. She was my champion, always encouraging Oskar to invite me over, pressing jars of pickled blueberries into my hands. I had given her a knitted scarf for her last birthday, covered with vikkel, travelling stitch, the edges woven through with braided ribbon. I could tell Oskar was pleased, although he would have preferred for us to meet in the wild, overrun orchard beyond the house or in the paddock where they kept a few straggly cows. Imbi was not one to be argued with, though, and she liked my company so the farmhouse was where we spent most of our time, telling stories or helping Aime with her schoolwork while Imbi plied us with small battered cakes she had fried on the griddle and doused in her own special syrup; an assortment of berries steeped in the honey of wild forest bees. It was only in the midst of preserving that Imbi seemed to forget we were there, too busy preparing the sugar-water and instructing Aime on how to steep the fruit to notice the sound of our footsteps and the squeak of the door as Oskar and I slipped into the forest to be alone.

Once there, we could sink down among the mossy tussocks and watch the clouds race by, imagining how our lives might be, if nothing stood in our way. Although I couldn’t go to university, I wondered aloud if I could one day write a book, a collection of all the stories my grandmother had told me. I would still have to mind the sheep, of course, and help my parents with the farmwork, but in my spare time, I would run the knitting circle and perhaps even take trips outside of Estonia to see the world. Oskar would be a carpenter like his father had been before he grew ill and died, leaving Imbi to raise their children alone. Imbi had been forced to sell Oskar’s father’s tools at the flea market to make ends meet but that did not dampen Oskar’s plans to one day rebuild his mother’s cottage from the finest oak, with heart-shaped windows and a grand kitchen where Imbi could spend her days preserving without worrying about milking the cows and churning butter until her hands ached. There would be a shelf in the parlour so Aime’s dolls could watch over her as she studied and a room with large windows facing the garden which let in plenty of light so I could knit in comfort, without ever having to squint down to check that my stitches were even. It was a dream-house, a fantasy built from years of refinement and the countless hours Oskar and I had spent lying side by side, lost in our thoughts beneath the peace of the clouds.

In all our dreaming, we always spoke of our future as if we intended to live it together. Our pairing felt as natural as the shifting of seasons. My parents, I hoped, would not deny the match. Imbi, I felt sure, would be overjoyed.

A grin spread over my face. A twig snapped beneath my boots, pulling me out of my daydream.

And then I heard the cows.

The sound echoed across the forest, slipping in between the trees, filling the space and freezing me in my tracks. Their cries were loud, desperate.

I paused at the edge of the clearing that held Oskar’s farmhouse. From where I stood, it looked unchanged. The funny crooked windows, the small barn tacked on to the side, the fragrant herb beds nestled against the path that led up to the front door. But then that sound came again, loud and shrill, full of pain. The cows were trapped in their barn. There was nobody to milk them or set them free.

My feet seemed to move of their own accord, propelling me towards the house. My breath came in short, sharp bursts. When I reached the door, it swung open.

I bent my head, listening. I wanted to call out. I wanted to hear anything but those pitiful cries from the barn. But my voice was trapped in my throat.

I stepped inside. Sunlight slanted across the floor, illuminating the dust on the old floorboards, carving up the room into light and shade. I squinted, waiting for my eyes to adjust. That was when the smell reached my nostrils, the cloying scent of burnt sugar. Something had been left bubbling on the stove, now nothing more than a blackened sugar crust.

I moved towards it, intending to lift the pan but as I skirted the table, my boots met something soft. I looked down.

Imbi lay on her back. Her face was frozen, eyes staring up as if she could see through the roof to the sky. Bullets had torn holes in her dress and there was a wound near her forehead. Her arms were flung out in warning or surprise. In contrast, Aime was curled on her side, arms wrapped around her middle. Her eyes were closed, the skin on her eyelids a pale crinkled blue like the crushed fabric of her doll’s dress. The sun streaming in caught the rosy highlights of her hair. She might have been sleeping.

I squatted down and reached out my hand to touch her shoulder. It was stiff and unyielding. Understanding struck and I shot to my feet, gagging.

Oskar, where was Oskar?

My face was hot. I forced myself to lurch towards his room. It was empty. Relief was quickly followed by terror. I needed to find him, but I could not do it alone. My hands shook so hard I could barely turn the door handle to fling myself outside.

I stumbled home in a fog of panic.

My father was inspecting fruit in the apple orchard. One look at my face and he ordered me to go into the house and find Mama and wait for him to return. Mama was in the laundry shed behind the house, plunging Papa’s soiled shirts into a bucket of grimy water. She looked up in surprise as I ran towards her. The shirt fell from her hands and splashed back into the bucket.

‘Kati! We weren’t expecting you back till tea time.’ She wiped her hands on her apron and came towards me. ‘What’s wrong?’

I tried to speak. My teeth chattered. Nausea churned from the base of my stomach up to my mouth. The words finally came in gurgles and gasps, like water running from a broken tap. I watched Mama’s face grow ashen and then her cold hands wound around me and she held me as if I was a child, smoothing back my hair with fingers which smelt of soap and tea.

‘Oskar,’ I managed to say. ‘Papa must find him!’

We went together into the house and I stood at the window at the back, my gaze fixed on the far paddock where the path which led to Oskar’s farmhouse began.

It was less than an hour before Papa returned, but it felt like so much more. Every moment he was gone had shown me Imbi and Aime’s bodies on the farmhouse floor interspersed with visions of Oskar lying bleeding somewhere in the forest. Even the warm milk Mama pressed into my hands could not melt the chill that spread through my body. I couldn’t imagine my life without him.

At last, I saw Papa emerge from the forest and cross the fields towards the house. His movements were slow, his body bent inwards as if he was walking into a strong wind. We hurried down the steps to meet him.

‘Well? Did you see them?’ Mama said when he reached the farmhouse. ‘It can’t be true. They’re not—’

She stopped, caught herself. Papa’s skin was the colour of oatmeal. ‘It’s true.’

Mama began to cry. A wave of dizziness made my head spin and I clutched at Mama’s hand to steady myself.

‘Did you find Oskar?’ I said.

Papa’s gaze swivelled towards me. There was a strange look in his eyes. ‘No,’ he said. ‘No, I did not.’ He said the words carefully, sounding each one out as if he was speaking for someone else’s benefit. ‘When I got to the farmhouse, there were NKVD agents already inside. They are coming to speak with us later.’

‘Perhaps they will find him.’ I hugged myself. ‘They will look for whoever killed Imbi and Aime, start an investigation.’

My parents exchanged a look.

‘We don’t have long,’ Papa said to Mama. ‘Let’s bring the sheep in. The cars might startle them.’

Something about his tone made me search his face. ‘Papa?’

He was already turning away. He looked back and his shoulders slumped. ‘Kati, there won’t be an investigation.’ I stared at him blankly. His mouth twisted. ‘Think; there can only be one group of people who hate Estonians enough to slaughter innocent women and children.’

I felt sick. A curl of anger twisted inside me.

‘We must be prepared for the worst,’ he continued. ‘Oskar is gone. We may never know what happened to him.’

‘But what reason would anyone have to hurt him? To hurt Imbi and Aime?’

Papa’s face darkened. ‘I ran into Johannes Tamm this morning. Did Oskar tell you that he whistled an Estonian song as the Russians marched past the market in Tartu last week? The soldiers did not hear but Tamm’s Russian neighbour did and he recognised Oskar and reported him. Tamm told me so himself.’

‘No.’ I tried to conceal the surprise and hurt in my face. Oksar had voiced his disapproval of the Russians to Imbi and me in private but I had not thought him so foolish as to publicly endanger his family. I could only guess that he’d thought the Russians would not hear him. If he considered himself in trouble, he would surely have told me. We had promised we would not keep secrets from each other. ‘He didn’t say a word.’

Papa looked towards the road, as if he heard the crunch of tyres. ‘When the soldiers arrive, we must say nothing to incriminate ourselves. You understand? You saw what happened to Oskar’s family. That is what happens to anyone who opposes them. Or worse. Think of your mother.’ I flinched. His voice gentled. ‘You must forget that boy, Kati, and hope for his sake and ours that he never returns.’

He wrapped me in a tight embrace. I wanted to hug him back, but I could not force my hands, my limbs stiff with shock and fear, to move.

Now, a year later, here was Oskar standing before me. How many nights had I dreamt of him, willed him back? But I had never imagined it like this; my parents standing silent, my father’s wary gaze. So much was different. So much had been altered by the continuing Soviet influx. Estonian families exiled or deported, their properties broken up into collective farms. Others ordered to leave their office jobs to work in the fields or consigned to the darkness of the mines. Villagers had been encouraged to join the Communist Party; anyone who didn’t was viewed with suspicion. Cars and horses, even bicycles, were confiscated. Families came home to find their belongings flung out into the street and strangers sleeping in their beds. Whatever the Russians needed, they took for themselves. Anyone who resisted was beaten violently or taken to the NKVD headquarters for interrogation. Papa was right; it was best to try to forget. If only it was so simple.

‘I’m sorry,’ Oskar said. ‘I’m so sorry, Kati. I didn’t realise.’ His voice was low, edged with pain.

I glanced up and our eyes met again.

I’d forgotten the paleness of Oskar’s blue eyes. In the lamplight, they were almost grey, a stream reflecting an autumn sky. They were the eyes of the man who knew me best. They could see past the thin barriers I had built to protect myself. Once, I had been able to read Oskar too. Now there was a veil drawn between us, a darkness that clouded my judgement. I had no way of knowing; had he missed me as desperately as I’d missed him?

Papa spoke suddenly. ‘Why are you here, Oskar? It’s late. We are tired. You’ve risked our lives by coming back. Tell us what you want and then leave. If it’s money, we have none.’

‘It isn’t money,’ Oskar said. He stole another glance at me before turning back to Papa. ‘Change is coming, Erich. It affects us all, but it will affect, most especially, your family. I have come to warn you that the war is coming to Estonia.’

‘Ridiculous,’ my father replied.