Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

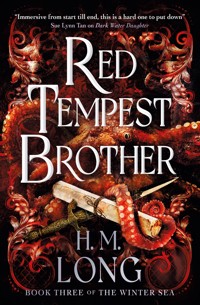

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: The Winter Sea

- Sprache: Englisch

The epic naval fantasy trilogy concludes, as Sam, Mary and Benedict play a deadly game of war and espionage on the high-seas. Perfect for fans of pirate-infested waters, magical bestiaries and battling empires, by authors such as Adrienne Young, L. J. Andrews and Naomi Novik. In the wake of the events of Black Tide Son, Hart flees into pirate-infested waters to shelter on the island where former rogue James Demery and the Fleetbreaker, Anne Firth, now rule. Reeling from their discoveries about the truths of the Mereish-Aeadine war, Mary and Sam hover on the precipice of a terrible, world-altering choice – they can stay silent and maintain their good names, or they can speak out, and risk igniting total war across the Winter Sea. Meanwhile, Benedict captains The Red Tempest, a lawless ship of deserters and corrupted mages in search of an Usti spy with incendiary stolen documents. Benedict is determined to make the truth known, consequences be damned. As rumours spread of a new Ghistwold sprouting in the Mereish South Isles, May and Sam sail once more into intrigue, espionage and an ocean on the brink of exploding into conflict. They must chart a course toward lasting, final peace, at the heart of the age-old battle for power upon the Winter Seas.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 553

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Map I

Map II

Part I

One: The Burning of Port Sen - Benedict

Two: Fire in the Fog - Mary

Three: The Liberation of the Hart - Mary

Four: Reckoning - Samuel

Five: The Red Company - Benedict

Part II

Six: Voskin - Samuel

Seven: The Fleetbreaker’s Daughter - Mary

Eight: Vachon - Benedict

Nine: The Convict’s Good Counsel - Samuel

Ten: Otherwalker - Mary

Eleven: Usti-Aeadine Relations - Benedict

Part III

Twelve: The Council of Lords - Samuel

Thirteen: Sister - Mary

Fourteen: The Oranmur Spur - Samuel

Part IV

Fifteen: A Trusted Advisor - Benedict

Sixteen: Ties of Spirit and Flesh - Mary

Seventeen: The Way of the World - Samuel

Eighteen: Correspondences - Mary

Nineteen: A Knife in the Dark - Benedict

Twenty: The Perils of Notoriety - Benedict

Twenty-One: Adrift - Samuel

Part V

Twenty-Two: The Cartographer’s Mark - Benedict

Twenty-Three: Whispers from the Cape - Benedict

Twenty-Four: Compass - Benedict

Part VI

Twenty-Five: The Sea of Spires - Samuel

Twenty-Six: Isla Ascra - Samuel

Twenty-Seven: Hidden Places - Mary

Twenty-Eight: The Ghisten Three - Samuel

Twenty-Nine: Forgotten in the Dark - Mary

Part VII

Thirty: Doldrums - Samuel

Thirty-One: The Balance of Power - Mary

Thirty-Two: Farland - Samuel

Part VIII

Thirty-Three: The Dreamer’s Wake - Benedict

Part IX

Thirty-Four: Southern Cousins - Mary

Thirty-Five: The Mirrored Deep - Mary

Thirty-Six: The Stone Forest - Mary

Thirty-Seven: The Shadows of Saints - Samuel

Part X

Thirty-Eight: Yissik Ocho - Benedict

Thirty-Nine: Elesi Artan - Samuel

Part XI

Forty: Thieves and Brigands and Brothers-in-Law - Mary

Forty-One: Comrades and Captives - Benedict

Forty-Two: The Market - Samuel

Forty-Three: The Blockade - Mary

Forty-Four: Mirror Twin - Benedict

Forty-Five: Return to Isla Ascra - Samuel

Part XII

Forty-Six: The Stranger - Mary

Part XIII

Forty-Seven: The Collared Beast - Benedict

Part XIV

Forty-Eight: Old Faces, New Threats - Samuel

Forty-Nine: Unexpected Allies - Mary

Fifty: Ice Bound - Benedict

Fifty-One: In the Well - Mary

Fifty-Two: Even Ground - Mary

Part XV

Fifty-Three: Two Summoners - Benedict

Fifty-Four: Regret - Mary

Fifty-Five: Tempest Choir - Samuel

Fifty-Six: The Indifference of Empires - Samuel

Fifty-Seven: A Fitting Gift - Mary

Fifty-Eight: Josephine - Benedict

Epilogue

Songs Referenced

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise for

THE WINTER SEA SERIES

“Black Tide Son was impossible for me to put down … I will devour every single book H.M. Long writes.”

Genevieve Gornichec

“Deftly executed and highly entertaining … A tale that deserves to rank alongside RJ Barker’s The Bone Ships and Robin Hobb’s The Liveship Traders in the top rank of maritime fantasy.”

Anthony Ryan

“A wonderful adventure! Dark Water Daughter swept me to the high seas with its captivating story, rich original lore, fascinating characters, and slow-burn romance.”

Sue Lynn Tan

“Outstanding naval fantasy; Robin Hobb meets Master and Commander.”

Peter McLean

“Beneath the swashbuckling surface of the tale, Long includes a thoughtful exploration of the nature of love, from fraught familial bonds to a sweet – but fierce – romance that will make readers swoon.”

M.J. Kuhn

“Swashbuckling adventure, magic and a slow-burn romance – I loved returning to this icy, watery world.”

Kell Woods

“A unique and breath-taking slice of high seas fantasy … I didn’t know I needed these fantasy pirates and their freezing ocean until they sailed into my life.”

Jen Williams

ALSO BY H. M. LONGAND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

The Four Pillars Series

Hall of Smoke

Temple of No God

Barrow of Winter

Pillar of Ash

The Winter Sea Series

Dark Water Daughter

Black Tide Son

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Red Tempest Brother

Print edition ISBN: 9781835411377

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835413548

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: July 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© H. M. Long 2025

H. M. Long asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)

eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, Estonia

[email protected], +3375690241

For Marco

MEREISH SOUTH ISLES —Comprised of some three thousand islands south of Mere and the Cape, the Mereish South Isles officially fall under the rule of Mere. In practicality, however, the islands are broken up under the governance of dozens of local warlords, monarchs, trade companies and rulers of other distinctions. These rulers are everything from pirates to royal exiles, hailing from across the Winter Sea and beyond, and are united under the banner of a so-called Unified Council of Lords. See alsoMERE, MEREISH, MEREISH NORTHERN ISLES, MEREISH-CAPESH ALLIANCE.

—FROM THE WORDBOOK ALPHABETICA:A NEW WORDBOOK OF THE AEADINES

ONE

The Burning of Port Sen

BENEDICT

Sometime between learning of the Usti spy’s escape and returning to the docks, my temper snapped. I knocked a lantern into a pile of refuse, glass cracking, oil spilling. My crew began to enact similar vandalisms with willful abandon, the invisible threads of my Magni power compelling their minds to vengeance and their hands to destruction.

Naturally, there were attempts to stop us. A musketball skimmed past my ear, loosed by one of the port’s converging guards, so I turned my power upon them. As I strode out onto the sprawling docks, the guards, then civilians, took up our task with startled, frightened and ravenous urgency. A little girl hurled rocks through windows, burning hay scattered about her small feet. Fishwives set fires, cart drivers knocked aside the poles of the market stalls and laborers began to dump goods into the South Sea by crate and barrel and upended basket.

The Port Mistress survived only by her honesty.

“South,” she said when I stood in her door, the streets a riot behind me. “The last ship was headed south.”

There was only one dock fit for a vessel as deep and grand as my Red Tempest, and it was to the end of this long, barnacle-crusted arm we strode as the fires spread. My influence followed me like the billows of smoke that drifted across the bay, wrapping about the other ships and prompting men and women to load cannons, swivel guns and small arms. Then they, as I willed, turned the lot of them upon the shore.

The Red Tempest did not participate in the bombardment of Port Sen. We sailed out long before the Port Mistress’s mansion toppled from its stilts and the battery at the harbor mouth exploded. I observed the chaos from Tempest’s deck, listening to the thunder of the guns and watching the inhabitants of the port scatter like rats, leaping into the water, fleeing into the hills and putting themselves out in boats.

The smoke trailed us out of the bay. I felt the sphere of my influence slip from the last of the anchored ships, and my world narrowed once more. The deck beneath my boots. Blood on my hands, though I could not recall how it came to be there. Hot breath raking from my lungs. The taste of sweat and smoke on my lips. The chanting, rolling, rumbling voice of my Stormsinger, summoning the winds that swept us away and prevented pursuit.

“Benedict.”

I turned, squinting smoke-burned eyes. Charles Grant considered me from a pace away, one restless hand on the hilt of his smallsword.

My attention caught on him like fingers on a crumbling slope. I corralled myself and straightened.

“No need for that,” I said, glancing back towards the port. Something stirred in me at the scene, a lightness that might have been excitement, or shock, or unease. I could ill define the sensation, but I was swiftly learning that reflection was arduous and uncomfortable. Particularly with the stink of smoke and gunpowder in my nostrils.

I pulled my baldric over my head, taking my sword and brace of spent pistols with it, and tossed it to Grant. He caught it, then coughed a protest as my soiled coat followed the weapons.

“Am I your fucking valet?” the former highwayman demanded, shaking his blond hair out from beneath the coat.

I ignored him, heading for the companionway.

“Ms. Olles,” I called to my first officer, a black-haired woman in her mid-thirties. “What is the nearest port?”

“Aside from the one he just burned,” Charles interjected, following me with my coat draped over his shoulder and my weapons in his arms. His tone was dry but I recognized his disapproval.

“To the south,” I clarified.

Olles shot Charles a quelling look. She was a good-natured woman, evidenced by the crinkles around her eyes and the laugh lines on her cheeks, but she had little patience for interruptions. Or Charles. “I’d need to see the charts, sir.”

“Fine, I will do it myself,” I said. “Send Faucher to my cabin.”

“Yessir.”

A few more paces and Charles and I were swallowed by the shadows of the first gun deck. We made for the stern, where the grand cabin lay, passing row upon row of nestled guns and sea chests in the close, brine-scented gloom.

In the cabin, Charles dumped my coat and weapons on a chair and moved to the stern windows, where he peered out at the shrinking, smoke-blurred visage of Port Sen.

“There will be repercussions for this,” he commented.

“One enemy among a thousand islands and a hundred lords,” I said, pouring water into a bowl on the central table then beginning to work the blood from around my nails. “Port Sen is irrelevant. Once we find Alamay, I will be the only one with true power in these seas.”

Charles sank down in a chair on the other side of the table. “I am still unclear as to how a stack of unverified documents will satisfy your megalomania.”

“You need not know.”

“Ah, now, see,” Charles raised a finger. “That is where you are wrong. Friends share their minds, Ben. I know you have very little experience in these matters, so you will simply have to believe me. Unless I am a prisoner, in which case, perhaps you would consider a villain’s illuminatory ramble?”

I shook pink water from my fingers. “Handkerchief.”

Charles fished one from his pocket and tossed it over. I proceeded to dry my hands, only to slow when I saw the embroidery around the cloth’s edges. “What are these? Nooses?”

“Yes, and there I am, hanging in the corner,” Charles replied, leaning forward to point. “Mary made it for me. Try not to stain it.”

“Mary,” I muttered, disliking the reminder of my brother and his… whatever they defined themselves as nowadays. The thought of them stirred a host of feeling and, admittedly, conflict, that did not bear contemplation.

I had left them behind, and for good reason. They had done enough for me. And to me. It was time to part ways and carve our own destinies.

The blood around my nails refused to come clean. I frowned at it and scrubbed, much too hard.

A knock came at the door and Jessin Faucher strode in, shadowed by two crewmen who remained in the hall. We were nearly of an age, he marginally shorter than I and dressed in a simple shirt, breeches, stockings and a straight-cut Mereish waistcoat.

He closed the door on the guards without a word and joined Charles and I at the table.

Charles, reclaiming his handkerchief, sighed at its condition and tucked it away again.

“You know these isles,” I said to Faucher. “I need you to determine where Enisca Alamay is most likely to try to sell those documents. We cannot chase her like blind dogs—we must get ahead of her.”

“So, she did escape,” Faucher clarified, leaning back to cross one knee over the other. His Mereish accent was marked but not burdensome, and he spoke Aeadine for my benefit. “I heard a commotion from my quarters, but my… escort… was unforthcoming.”

“Kapper saw her board a ship leaving harbor. There was no time to get word to Tempest to stop her, and as I cannot fucking fly, there was nothing I could do.”

“Ah. And we have no notion of where she went?”

“South.”

“Nearly everything in the isles is south of our position. That is vastly unhelpful.”

“She may not intend to sell them,” Charles pointed out with an air of weary repetition. It was not the first time he had waged this battle. “She is more likely intent on some Usti stronghold where she can disappear or find aid. Send the papers home.”

Faucher shrugged. “You know her better than I. But I know the isles, yes. And I am glad to share that knowledge in return for greater freedoms.”

“I am not releasing you,” I stated.

“Freedoms,” the Mereish man repeated. “I have no interest in leaving my ship.”

I held his gaze, a reminder that The Red Tempest was now my ship poised on my tongue. But he knew that well enough, and I would not rise to his provocation.

He would, naturally, attempt to retake the vessel if the opportunity arose. I would have thought less of him otherwise.

“Give me a location to begin and we can discuss these freedoms,” I countered. “Particularly if you can tell me where to hire a Sooth.”

Faucher thought for an instant, tilting his head back to stare up at the beams of the ceiling. Then he sat forward and rested his elbows on the table. “I agree with Charles. If I were her, I would make for Usti waters. That likely means the Sea Hag, the Indry or Krekhafen. We can hire or buy a Sooth in any of them.”

“The Sea Hag,” Charles repeated with a snort. “Did she give herself that title?”

“Actually, yes,” Faucher’s lips turned in a small, dry smile. “Which tells you something of her nature.”

I had heard of the Indry, but neither of the others. I did not, however, admit my ignorance. “Which is the closest?”

“Krekhafen,” Faucher replied. “It is ruled by exiled Usti royals, from a dispossessed line. There are more than a few of them down here, vaguely allied with, and casually hostile to, one another and everyone else. All distant relations of the current queen. Krekhafen in particular would both be an easy place for an Usti to blend in, and a very, very good place to sell secrets that might overturn the current crown. If they so desired.”

“Very good. Where is Krekhafen? South, I presume.”

“In a manner of speaking. One must go south to get there.” Faucher moved to one of the bulkheads, where numerous charts were pegged. “This is Port Sen.”

“Was,” Charles corrected.

Faucher cleared his throat and moved his finger across the heavy paper. “This is Krekhafen, here, in the west. In between, here, is this arc of islands. This is under the control of the Mereish Trading Company, and thus the Mereish Navy. They have multiple strongholds throughout the islands, do be aware of that. I do not recommend catching the attention of either the Company or the Navy, particularly as they will have stronger ties to the Ess Noti and their augmented magecrafts. Also, the events at the Anchorage and the fate of my ship may be known already. The war will bleed south.”

“Company waters might provide an opportunity for your rescue,” Charles pointed out. He considered the other man dubiously, then looked at me. “Are you bewitching him?”

I felt a flicker of offense. “I need not always enthrall everyone in my company. You bear with me.”

“Our bond, as established, has been forged through great travail. And abduction,” Charles pointed out, a little distractedly.

Faucher laughed without humor. “As I said before, I have no desire to leave my ship. I, too, wish to find Enisca Alamay and those documents before they land in the wrong hands.”

The conversation continued for some time, including further discussion of charts and courses. Regardless, the first order of business remained to find a Sooth, so I sent Charles above with the word to make for Krekhafen. Faucher I banished back to his quarters, trailed by his guards, and I was finally left alone.

I remained at the table, where the bloodied bowl of water sloshed. It was more brown than pink now and made my stomach turn.

Or, perhaps, it was not the blood that made me ill. Perhaps it was the memories flickering through the back of my mind, glimpses of burning buildings, of people throwing themselves from the docks. Of a little girl, mindlessly throwing a rock at a window as flaming hay scattered around her skirts.

Another time, I might have cut that imagining off. But I found that I was drained, my mask of indomitability slipping. My discomfort grew.

I leaned forward and a Sooth’s talisman, warm from my skin and tarnished from constant wear, swung out over the table.

In a flash, I saw another little girl. Her face was vague, a mix of the infant I had once seen and the shadow of my mother. My eyes peered out of her small face as she became the girl from Port Sen, in my thrall, throwing stones and unaware of the fire around her, the danger on every side. Then she was elsewhere—tucked into a shadow. Beneath a bed? Behind a door?

I shoved the talisman back under my shirt, scrubbed bloody water across my face with brusque hands, and walked away.

TWO

Fire in the Fog

MARY

After surviving the greatest naval battle in a century and carving my name among the most powerful Stormsingers in history, being outwitted by pirates barely a day into the Mereish South Isles was, mildly put, demoralizing.

I considered the depth of my misfortune in a bleary, half-feeling way as I lay like a starfish on the sand, staring up at cool drifts of fog. The wind smelled of brine and rotting seaweed, but also cedar and greenery, and the rich damp of deadfall. The latter, I suspected, was entirely my imagination. I had just been blown overboard, half drowned, and taken a solid knock to the head—it was only natural that my mind would retreat to where I felt the safest. A Wold in the mist, tucked at the feet of slate grey hills.

Something pinched me. I rolled my head to see an oddly opalescent, and rather gigantic, crab plucking at my sodden shirtsleeve. I squinted at it, still not quite rooted in reality, but the second pinch—or rather, the creature’s attempt to pull my flesh from my bones with one long, serrated claw—set me right.

I shot up, blacked out, and woke up again with the creature hauling me into the surf by the ankle. I shrieked, flailing and kicking, only to receive a mouthful of water and sand for my struggle.

My hands moved without my prompting, jerking a knife from my belt and twisting. I stabbed the blade down at the joint below the claw once, twice. My knife deflected, striking only sand and water. I writhed like a cat on a string and shouted my horror and defiance.

A third stab. I felt the blade dig into a chitinous limb.

The claw released. I flipped, crawling then stumbling back onto the shore. Just out of reach of the lapping waves I collapsed against a rock, hip high and oddly flat on top, then proceeded to gasp and curse and spit water, gritty sand between my teeth. My ankle bled freely, stinging with salt, but I had eyes only for the waves. I stared to and fro, sure at any moment the giant crab would come back to snap off my feet and crush my skull.

The waves simply lapped, smoothing away the signs of my struggle into a flat, pale beach.

“We should have stabbed out its eyes,” I rasped, but instead of sounding fierce I put myself into a fit of coughing. I set the knife down and braced on the rock, retching seawater and bile.

In its defense, you did look dead, Tane’s voice replied in the confines of my mind.

Hush.

Still coughing, I assessed my condition. I wore sodden trousers, belted, a torn shirt and stays. There was a swollen gash on my forehead—the source of the blood—and only one shoe had survived my swim. My hat was nowhere in sight, nor were my pistols, and the twists of powder and shot in a pouch at my belt were soaked.

I pulled off my useless shoe and set it beside my knife on the flat rock, still eyeing the waves.

“One shoe, a knife and five bits of wet shot,” I summarized. “Samuel had best find me soon. I am ill-equipped.”

The ghisting in my bones did not reply, but I knew her thoughts. They spun back to Samuel, Hart, and the battle I had been so abruptly removed from, tossed overboard by a cunning gust of wind as we fended off petty local pirates and their surprisingly deft Stormsinger.

My stomach began to turn. I could not fear for Hart, I told myself, not truly. He had survived far greater foes.

Then why could I not hear cannons, or bells, or voices? The engagement had been within sight of shore, at least before the fog had rolled in.

I surveyed my surroundings more intently. I stood at the center of a circle of stones on a flat expanse of sand, all of them knee-high and surrounded by the sea fog. The stones were narrow, weathered by centuries of exposure. The larger rock I leaned against was different, however: broad and flat, dark with damp and rimed with salt in the muffled light. It looked, oddly, like an altar.

No, it was an altar, complete with carved trenches for blood and wave-worn symbols.

That felt like a bad sign.

I snatched up my shoe and knife and limped from the circle.

I stared out at the veiled, disconsolate sea as I fled. It was growing darker and the water was cold, even this far south. I whistled to the wind and the fog shifted, granting me a clearer view. Inland, the sand continued as tidal flats, interrupted here and there by sheer shoulders of rock and sea stacks twice my height. These were capped by dense forest, blurs of green leaves and reddish bark. A few toppled trees lay here and there upon the sand, smoothed by time and the waves, and bleached by the sun.

There was no sign of Hart. No sign of Samuel. No sign that any human had trodden this shore, save the macabre stone circle.

We need to see further.

I began to hum, swaying slightly as I eased the weight on my clawed ankle.

New tendrils of wind stirred the mist into eddies about my sodden form. They brought a host of information, glimpses and sensations. Salt. The wash of waves on sand, their crash against rock, the slop of seaweed and debris. The dart of little birds in and out of crags in the sea stacks. The whispering of the forest and the distant cries of gulls.

Voices. Voices shouting.

An explosion.

I took off at a stumbling run.

Smoke gusted past me as I staggered around the foot of a rocky peninsula. Beyond, the miasma dissipated into scattered banks, dragged across a tidal flat surrounded by rocky coastline, smooth beaches and lush, temperate forests of cedar, hemlock and spruce. Further out to sea the smoke relented to natural, wispy fog, revealing dozens of scattered islets.

My stomach lurched. There, on a barren tidal flat between rivers and listless pools, lay Hart. Beached by the tide and toppled against one of the rock towers, his wounds were laid bare: a toppled mast, another visibly cracked and threatening to split, and a shattered section of hull spewing fire and flotsam. The ship’s grand figurehead of a rampant hart was half-buried, rammed into ridges of sand. Indigo ghisten light flickered across the wreck, spasming, trying and failing to heal wounds that could not be closed.

Nausea overcame me and I doubled over. My mind felt numb, my ears ringing. Surely, this was not real. I was delirious, dreaming, still adrift in the waves.

But the horror continued. The crew were little more than specks at this distance, but the wind brought me their cries of coordination, panic and pain. Ripples of musket fire and the deep boom of cannons sounded again and again. The latter echoed through the stone towers and muffled in the fog as I sighted its source—a small, swift sloop anchored before an islet, masts separating from the blur of conifers that clustered its shores.

The mouths of long guns flashed again, echoing across the sands as I saw a second vessel, twin to the first. This one was much nearer, nosing along what must have been a steep drop in the seafloor. A flag rippled lazily from her maintop, bearing the empty-eyed profile of a wolf skull, stuck through with a vertical, thick-bladed machete. The field behind the head was yellow and blue—Capesh colors.

I hobbled into the shelter of the nearest sea stack and took a moment to calm my thundering heart.

“So much for petty pirates,” I muttered, my voice thick, my mind numb. “Why are they still firing? They’ll destroy Hart.”

Perhaps that is their intention.

Another volley of cannons made me peer around the stack just in time to see an explosion of sand near Hart. The moving specks that were the crew—my crew—scattered with more shouts and screams.

I had to act. I edged back out into sight, marking the position of our enemies as I dragged ragged air into my lungs and began to sing a chanting song. “And the coming wind did roar more loud, and the sails did sigh like sedge…”

The winds came, weaving, then rushing, then roaring. They whipped damp shanks of hair into my face and snatched up the sea fog, driving it into a protective barrier between Hart and the pirates. Other winds lashed out, sending the enemy ships creaking and rocking. Shouts and cries came from them now, along with the song of their Stormsinger.

I kept close to the stack. “And the rain poured down from one black cloud, the moon was at its edge.”

My fear and anxiety began to disperse into the wind, borne away and replaced with a grim exhilaration. It bloomed in my chest, pushing my shoulders back, making me a wind-harried shadow on the sand. I edged further out into the open, keeping my prey within sight as I reveled in the feeling. This was retribution. This was salvation. This was power—

A cannonball slammed into the stack behind me. Stone exploded, peppering me with fragments as my song turned into a shriek and I cowered away. Another, then another ball hurtled past me and I had no choice but to take off at a tottering, flailing sprint, barefooted as a billy goat but not a fraction as deft. My head ached. My ankle throbbed. The whistles of the shots gave me only momentary warning, particularly when those whistles turned into the deadly shrieking of canister shot. Rogue threads of wind blasted sand into my eyes before my own winds could stop them, and I flailed on in blindness.

I toppled behind a barnacle-covered boulder as shrapnel and musketballs peppered the area around me. Breathless, I cobbled together a few more lines of song. Fog immediately shrouded me and when more shots came, they were further afield.

That was foolish, Tane observed.

I realized I was still carrying my useless shoe and hurled it aside with disgust.

Gathering my courage I set off again, keeping low and pulling the fog around myself. I sprint-hobbled across an open expanse of tidal sands, leaving a drunkard’s path of dry-edged footprints in my wake. I splashed through pools and creeks rather than taking the time to circumvent them. Spurts of water from subterranean clams chased me as I navigated a rocky patch, darted around more sea stacks and squished over seaweed.

I saw the first body tangled in that seaweed, half-hidden by the fog. She lay face-down, more of the massive crabs converging on her spilled intestines in a pool of pink water.

I couldn’t tell who it was. I couldn’t look closer, could not afford to break down. I coughed back a surge of bile and carried on, giving her and the crabs a wide berth.

I passed other debris now, tangles of rope, pieces of hull—some from Hart, new and raw, others old and wave-battered and smooth—signaling we were not the only vessel to run afoul of this bay, or the machinations of the pirates who had driven us here.

I was just beginning to fear I had bypassed Hart entirely when figures burst around a massive sea stack, helping one another towards shore.

“Mr. Keo!” I shouted, as loud as I dared.

“Ms. Firth!” he called back. “They are coming ashore!”

My beleaguered heart slammed in my chest. “Where is Sam?”

“Gone for the ghisting with the Uknaras!”

Relief that Samuel, Olsa and Illya were alive collided with numb understanding. The ghisting in question was undoubtedly Hart himself, the spectral creature who inhabited the figurehead of our ship, guided and guarded it. But if they had gone back to the ship for the ghisting, that meant only one thing.

Hart, the vessel that had granted me freedom, where Samuel had found his redemption and where we had begun to build new lives, could not be saved. And, in fulfillment of a captain’s last duty to his vessel, Samuel would try to salvage the ship’s ghisting—even while the enemy advanced and the ship burned.

“Send us what hands you can!” I shouted to Keo. As far as the chain of command went, I wasn’t part of it, but he nodded his affirmation.

I took off again, following their footprints and cursing my ankle. I wanted to sprint, to fly, to already be at Samuel’s side.

My impatience, however, was unnecessary. With a swirl of fog the hulk of Hart loomed before me, figurehead tilted to one side, the great stag’s open, baying mouth soundless in the haze. My heart wrenched but I carried on, picking my way over broken sections of hull and fallen yards and spars.

“Sam!” I shouted as another explosion shook Hart. Fire plumed. Heat buffeted me, light blinded me, and all at once I was in another place, another time. Standing over another blaze, with Silvanus Lirr’s hand on my back.

I stumbled over a body, still twitching in a tangle of lines and torn sailcloth. I instinctively reached out to steady myself on a pile of debris, noticing too late that it was a cannon—hot and steaming and embossed with depictions of conquerors astride armored horses. I jerked back a scalded hand.

I froze in place, eyes pinned closed. I counted a handful of breaths, each one pummeled by the hammering of my heart.

Then, slowly, I forced my eyes open again.

The fire remained, but there was no Lirr. No frozen Ghistwold. No flames rushing over my skin.

Just the dying ship, the billowing fog, and Samuel Rosser.

THREE

The Liberation of the Hart

MARY

Samuel emerged from the murk like a specter. He was tall, his well-formed frame clad in a blood-stained shirt and his brown hair a tangle about his face. My relief at seeing him was tempered by the firelight that spilled around him, casting harsh shadows across his face, and glinting off the axe in his hands.

He didn’t appear to have seen or heard me, my calls drowned by the roar of the flames. Grim with determination, he mounted the wave of sand towards the figurehead’s great, baying head. Then, backed by smoke and fog and encroaching firelight, he began to hack.

“Mary.” I startled as Olsa Uknara appeared, followed by the larger figure of her husband, Illya. “You lost your shoes.”

“I have,” I huffed, and it felt like a sob. I clutched the wrist of my scalded hand, though Tane had mitigated the pain. “I’m glad you’re alive. Both of you.”

Illya saluted in reply, making for Samuel. As he joined the other man he hefted another axe, weighty and sharp, and spoke to our captain.

Sam turned, finally catching sight of me. Hart’s neck gaped open above him, chipped wood raw, and the creature’s great antlers spreading like the branches of the tree the ghisting had once inhabited.

“Mary,” Samuel panted. For an instant he was still, gaze flicking between me and the miasma around us, then he hefted the axe again. “Give us cover? They will soon be—Down!”

Olsa hauled me into the shadow of the hull.

My startled protest was lost in a cacophony of booming cannons and shrieking shot. Canister shot raked the wreck, lead balls slamming into wood, shards of metal tearing into sand. I saw the body I had tripped over twitch with impact—one of the bosun’s mates, I dimly recalled, and gagged.

“Thank you,” I panted to Olsa, pressing my back into the hull, then jolting away. The hull was hot, not to mention sharp with barnacles. They plucked at my clothes and the stink of green, briny growth assaulted me, along with the hiss and whine of heating wood.

This had to stop. I felt half mad, assaulted by threat and discomfort on every side. Sweat and seawater made my clothes cling to my body, sticky and hot. The fog felt like a weight in my lungs, too thick, and growing thicker with trapped smoke.

The thudding of the men’s axes resumed, faster than before.

“There’s no chance of saving the ship?” I asked Olsa as she took a knee, unslinging her rifle and beginning to load it.

“No. Just the ghisting.” She shoved a ramrod down the barrel of her gun and deftly clicked it back into place. She nodded out towards the enemy. “Which is all the Capesh care about.”

I looked up at Hart again, eyes burning with more than smoke. Suddenly, it made sense. The Capesh and Mereish were allies, largely due to the fact that the Capesh had no Ghistwold and relied upon the Mereish for their ghistings.

To a people with no Ghistwold, Hart would be the greatest treasure.

A protective instinct—Tane’s or mine, I could not tell—made me reach out. I rested my fingers on a bare, hot portion of hull between cracking barnacles and melting oakum. Light skittered across the wood in response. Another light wreathed my fingers as Tane began to whisper to Hart, their words susurrating back and forth in a language of imagery and emotion too fast for me to follow. But I felt Hart’s distress, his rage, his drive to protect his ship. So too I felt Tane’s need to save him—the desperation and determination of a Mother Ghisting.

Child, she soothed, before her will rushed through me like a gale. Sing, Mary.

“Samuel!” I shouted over the noise, backing away from the ship—lingering strings of luminescent ghisten flesh stretching between my fingers and the wood. My eyes stung, but I blinked the smoke and tears away. “I intend to sink them! Are you opposed?”

Wood exploded somewhere above and the ghisten light skittered away from me and back to the figurehead, casting Sam and Illya’s laboring forms into cavorting silhouettes.

“Leave one, destroy the other,” Sam bellowed in return. “They took my ship from me. I will fucking take theirs!”

The rage in his voice was enough to make me pause. For half a breath I stared at the fury in his half-lit face and the taut lines of his body. I hardly recognized him—or rather, I recognized someone else. Benedict. Wrathful. Unchecked. And even as my blood rose, my own rage boiling in sympathy, I was uneasy.

“Now,” Olsa urged. Her eyes had a distant quality, one that told me she looked beyond this tidal plain, into the Other. “They are nearly here.”

I shifted my shoulders purposefully, pushing away the image of vengeful Sam, my worry for Hart and our own lives. Remaining in the shelter of his beached hulk, I began to sing again.

“About, about, in reel and rout, the Death-fires danced at night.”

The first wind came swift and cold, dispersing the fog between me and the enemy vessels. I saw their forms as shadows in the deepening twilight, their lanterns extinguished. There were figures on the sand between those ships and I, advancing at a jog. Muzzles flashed again, this time smaller and closer—rifles and muskets.

“The water, like a witch’s oils, burnt green and blue and white.”

Another wind came, arching over the islands and seastacks with a great rocking of trees. It swept what was left of the fog and smoke out to sea, momentarily suspending us in a genuine, windy twilight, cold and brisk and tasting of salt.

Clouds rippled out across the newly visible sky like a shaken cloak, and the hail began. It rushed past us in pelting arms, pummeling the sand and converging on our enemies.

“And some in dreams assured were, of the spirit that plagued us so,” I sang.

Another voice began to clash with my own, equal parts breathless and urgent. The enemy Stormsinger, here, on the sand.

I squinted through the growing murk, searching for my counterpart. That figure? No, that was a man. That one? No, she could hardly sing so steadily at a run. She must be further back, sheltering behind her crew. Hiding.

“Come wind and sleet and woe...” Her words snatched at the wind and tossed it back upon us. Smoke wafted into my face, hammering hail advanced upon us, and my song stifled in a fit of coughing.

“Mary!” That was Illya. “Stop them!”

“Nine fathom deep he had followed us,” I rasped. By now flames had completely engulfed Hart, its light blinding and the heat rolling out in great, sickening streams over our heads. “From the land of mist and snow.”

Figures burst into view—but not from the direction of our enemies.

“Captain!” shouted the familiar form of Mr. Penn, his bald head streaked with blood and soot.

A dozen crewmembers led by Mr. Penn joined us beside the wreck, bearing muskets and a torn section of sailcloth. Some immediately sheltered behind piles of debris and trained muskets on our attackers, cracking off shots at will. Others joined Samuel, our helmsman spotting him out with the heavy axe.

“About, about, in reel and rout, the Death-fires danced at night,” I cried again. I flung the wind back at the enemy, blood racing, my face flushed with frustration and exertion.

The hailstorm swirled, now trapped between the wills of two Stormsingers.

Samuel stepped down beside me, his face slick with sweat, his shirt sodden and singed. He accepted a musket from Penn with one hand and snagged mine with the other, squeezing my fingers. It was a momentary contact, a flicker in my awareness, before he shouldered the weapon again. He stepped partially in front of me and knelt, facing our attackers.

Short as it was, his touch pulled me back into myself. I summoned the winds and crouched behind him, resuming my previous song but shifting it into a more ominous, more haunting key. The weather responded in kind, adopting my mood.

Inspired by the banners of flame overhead, I held the hail at bay while I sent a subtler wind to blow, gently and steadily, across Hart. It snatched sparks and embers and bore them across the tidal sand like a thousand fae dragonflies. Then, in a glistening stream, I hurled them not down upon our attackers—as the Stormsinger would expect—but on their distant, vulnerable ships.

I did not have time to see if those sparks found tinder. Samuel’s musket cracked, the taste of gunpowder bit at my nostrils, and with a fateful thud, Hart’s severed head tumbled onto the sand.

I couldn’t help but stare, even as enemies sprinted towards us, as the fire raged and the other Stormsinger’s voice rose. The hart’s baying head settled, frantically pulsating with ghisten light. It became brighter and brighter as the flames picked up, taking advantage of the ghisting’s impending departure to devour the ship more freely.

Within my bones, Tane roiled. I had rarely felt her this agitated, this close to the edge of her own, seemingly endless control. Ghisten light rippled across my skin as she threatened to manifest, her drive to go to Hart nearly overwhelming her need to stay with me and keep us alive.

So long as we remained in contact, we were nearly immortal. But caught separate? I would be another body on the sand, and Tane would cease to exist.

“Stay down and take this!” Samuel thrust his rifle into my arms and bolted for the fallen figurehead, shouting as he went. More crewfolk joined him and together, they rolled Hart’s head into a bundle of canvas and rope.

Another musketball skimmed past my arm. Tane surged to the surface, her ghisten flesh now sheathing my flushed, baking skin. I did not raise Sam’s rifle—I barely remembered it was there, slack at my thighs. Instead I hummed, catching up a fresh wind and, lastly, casting fire from the blazing ship lower across the sand like crackling war pennants.

Oncoming enemies shied, granting me enough time to watch as the ghisting Hart finally, irrevocably, fled the ship’s crumbling wood.

He poured into the half-shrouded head in a thousand visible threads of ghisten flesh. The threads came faster and faster, converging on the figurehead until, at once, the ship was devoid of light and Hart resided entirely in that single, salvaged chunk of wood. Then it too extinguished, save for a thin sheen over the weathered surface.

“Mr. Penn, see Hart into the forest! Guard him!” Samuel called over the roar of the flames. “The rest of you, with me!”

FOUR

Reckoning

SAMUEL

Water splashed around my ankles. Something low and hulking scuttled from my path—a massive crab, of all things—and I hit the sand once more, boots gouging, muscles burning. Despite the cool of the wind my skin felt hot, seared by the fire. Sweat stung my eyes and a ringing persisted on the edge of my hearing.

These discomforts, however, were distant things.

Pirates burst into sight, shadows and swirls and flashing muzzles.

“Beware!” I roared and ducked, easily avoiding a peppering of shots aimed in my direction. I already knew the path of each, just as I knew which of the figures was the pirate’s captain.

He hovered at the rear of his charging crew, a woman at his back. His Stormsinger. The very one that had blown Mary overboard, forced us into the inlet, and ensured the destruction of Hart. Of my ship. Of my home. Now, they would kill us, capture us, and take Hart for themselves.

I would not let that happen.

Mary joined me and we skirted a deep pool, rimed with seaweed and detritus, then nipped into the shelter of a seastack.

I paused just long enough to squeeze her hand. It was cold, her skin gritty with sand. “Take the Stormsinger, I have the captain. Ms. Skarrow! Give us some cover!”

The chief gunner Skarrow joined us, along with the dark-skinned Ms. Vin. Both set to reloading their rifles with admirable efficiency, Vin flicking one of her dozens of tight, thick braids out of her amber eyes. I reloaded, then peered out from behind our shelter as Mary began to sing.

At Mary’s word, hail surged across the sand in a vicious, hammering whip. It struck the enemy with sand-churning force, followed by a bank of fog as thick as the smoke that billowed from Hart.

There was a breath of quiet. The long glint of the barrel stretched before me as a single figure flitted across my sight—or rather, the empty space where my Dreamer’s Knowing told me the enemy captain would soon be.

I fired. A figure dropped and shouts and warnings exploded in the night. The enemy, rather than retreating as their captain hit the sand, rallied. There was a recklessness to their cries, a mindless desperation that chilled me and recalled me to other battles—of the armadas clashing at the Aeadine Anchorage, and the shrieks of drowning sailors. Of my own crew over the past hours as we were harried, run aground and battered to pieces. Of seeing Mary swallowed by the waves, and the thud of Hart’s head hitting the sand.

My rage returned in a flash of heat, then a rush of cold. I reached for another twist of powder and shot in my pocket.

I found none.

The enemy was paces away now, drawing swords, raising pistols. I flipped my rifle around, stepped from the shelter of the stack and swung it like a club.

I took a man full across the side of the head with a crack. He crumpled into the seastack as I seized his sword and sidestepped a musketball, which cracked off the rock in a peppering of shards.

“Your captain is dead!” I shouted. “Surrender!”

A moment of reprieve, another uncanny hush. Mary hovered at my side, hair and skirts rustling in a wind I could not feel.

A pistol cracked.

I seized Mary around the waist and pulled her from the path of the shot. I felt a rush past my ear, a spark of pain, then someone bowled us over.

We hit the ground. Mary gave a squawking shriek that I would have, under any other circumstances, been forced to mock. But just then our attacker decided to strangle me.

I clutched at the arm locked around my throat and with one hand reached back to grab their collar. I hurled them over my head and slammed them into a shallow, tidal creek. They twisted. A foot connected with my jaw.

I reeled into blackness. Then there was water in my nose and mouth, a great slap of cold on my hot skin. I rolled onto my hands and knees and staggered upright, spitting blood and sand and feeling, for all the world, like a monstrous, shadow of a man.

Like Benedict. Like Benedict had been.

That realization struck me like another, colder wave and I swayed on my feet.

Calm. Steady. Calculated. That was what I needed to be, for my crew, for Mary. For Hart.

Fog began to flee on a gentle breeze. The tide was coming in again, a gentle spreading of creeks and pools and an onset of waves. Bodies lay here and there. Someone was shouting in Capesh, repeating themselves over and over again—“Mercy! Mercy!”—and gradually, pirates began to surrender.

They were thrust to their knees by my victorious, bloodied crew. Mary was among them, soaking wet from our tumble and assisting Mr. Keo in gagging the enemy Stormsinger with a kerchief. The woman, pale blonde and not much older than Mary herself, still struggled.

“Surrender!” I called across the sand, my voice chasing down the last, far-flung figures. My mouth tasted of iron and I could feel blood in my beard, clotted with sweat and sand. “Surrender and live, or fight and die. The choice is yours!”

The last of the enemies dropped their weapons and the Stormsinger relented. The fog fully retreated, and we were granted a full view of the bay, the seastacks, the cliffs and the damp green of clinging trees. One of the enemy ships blazed, billowing smoke and flame and already half sunken in the shadow of an island as the remains of her crew staggered ashore. The other lay at anchor, longboats bobbing along a swiftly vanishing shoreline.

Water crept across the sands towards the smoldering remains of Hart. The tide was coming in.

“Bind and bring them,” I ordered my crew, trying to shed the shadow of my brother as I did. However hot my blood still ran, however angry I was, I could not lose control.

I turned from Hart’s wreckage and focused on the remaining pirate vessel. “I want to see my new ship.”

* * *

The Capesh vessel Ata Lapa—roughly translated to Sun Sparrow—was a serviceable but small ship, intended for darting between islands rather than the rigors of open sea. She had no ghisting, as anticipated, nor even a common figurehead, and her crew was a surly, unhappy lot. I could hear them chanting vengeance from the hold as I lingered on the deck, watching the sun rise.

If we were ever to return north, I reflected, I would need a new ship. If I could go back north. In that moment, the entirety of my future seemed grim, scarred by failure and loss.

I had been offered a Naval commission and rejected it. We had broken contract with the Usti, made ourselves personal enemies of the Mereish, and turned our backs on the Aeadine. My Letter of Marque and Mary’s contract had burned with the ship. We had no credentials, no protections and no accessible funds.

My thoughts dulled as dawn broke in a haze of orange and pink cloud, cast over a horizon of brooding red. Gold struck the waves as the tide, once more on the wane, withdrew from the islands, the seastacks and the charred remains of my ship.

Every scrap of wood was blackened, desiccated and crumbling, unfit to host ghisten life. Cannons jutted here and there, and the sand was cast with wave-washed rimes of debris. There was nothing living, save the crabs who preyed upon the dead.

A rifle cracked and my attention shifted to several of my crew, wading through the receding water. One of the great crabs ceased its attempts to tear the limbs from a corpse and scuttled away. The crewmembers converged on the body, hefting what was left onto a makeshift litter. At this distance, I could not see who it was. It did not matter who it was, perhaps. They were one of my crew, and I had not been able to save them.

I dug my nails into the rail of my commandeered ship until my forearms ached and my fingers felt like they would crack. The pain, however, was grounding.

“Take the longboat, fetch Penn’s crew and the figurehead,” I heard Mr. Keo direct the crew. “Ms. Skarrow?”

“Gone, sir.”

Ms. Skarrow was dead? When? I recalled the last moment I had seen her, but could not pinpoint the moment of her death.

There was a moment of silence. I released my breath slowly, steadily, and pushed the dead woman’s memory from my mind.

Keo went on. “Simina, divide the remaining able-bodied between getting this tub ready for open sea and joining Severn in the search for bodies.”

“Sir.”

More conversation and orders passed, ringing out of my comprehension, then I felt a presence at my side.

“The prisoners need to be set ashore,” Mary said, lowly. Beneath us, the stomp and chanting of the Capesh pirates continued, backing her words. “This ship isn’t big enough for all of us. And we should also rename it quickly. The prisoners insist they’ve friends who will come for them, so we need to disappear.”

“Agreed.” I looked at her, searching for… something. She wore a coat that was not her own, had one hand bandaged, and she favored her left foot. Her eyes were rimmed with fatigue, her hair in a careless knot at the nape of her neck.

I took the side of her windburned face in one hand and, my lips a breath from hers, looked into her eyes.

She stared back, startlement twining with worry. “Sam?”

“I am searching for an anchor.”

She was quiet for a moment, her gaze gentling. “Have you found it?”

I kissed her, gentle and lingering. Her lips were dry and tasted of salt, but the feel of her, the scent of her skin beneath the seawater and smoke, dispelled my doldrums.

“Yes.” I began to lower my hand, but she snared it between both of hers—her skin finally warm, though rough with bandages—and held it close.

“We are alive,” she told me, intuiting, somehow, what I needed to hear. “We are alive, as is a good portion of the crew. We have a ship, and we did not lose Hart himself. All we need to do is reach Demery, and we can… We can mourn. And decide what to do next.”

I nodded. “Are you well?”

“One of the crabs tried to eat me, but otherwise, yes,” she said with a humorless smile.

I returned it, hard-edged and grim, then glanced about the deck. “I suppose my charts are lost? We will need to locate the nearest port, preferably one which is not governed by pirates, though I realize that may be too much to ask.”

“Port Sen,” she said promptly. “Poverly saved the charts. I’ve already looked them over.”

“That is something,” I admitted, glad in the same breath to know that the steward’s girl was alive. Without real hope I ventured to ask, “Was anything else saved?”

Mary rubbed at her face. “No.”

A moment of strained silence.

“Tell me of Port Sen,” I said, pushing the disappointment aside.

“It’s an open port—a pirate port—but well organized and affiliated with the Council of Lords.”

“That does not mean it is safe.”

“No, but it is our only option. I don’t suppose they would have a proper inn? With a hot bath?”

“If they do, I will gladly help you into it.”

She smiled again, but this time with feeling. The shadows around her eyes, however, could not be completely dispelled. “Sam… Demery’s island is ten days away. Hart barely lasted one in the South Isles.”

“We were still damaged from the Anchorage,” I admitted. “Ill-prepared, and that negligence is mine to bear. We should have made port sooner.”

Mary prodded me in rebuke. “Where? The Mereish mainland? We had no choice. Now, decide what to name our new ship.”

I eyed her. “That hardly matters.”

“Name it.”

“Nothing comes to mind. You do it.”

“Reckoning,” she said with a light to her eyes that, while harkening to the lawless side of her I had always rebuked, stirred me. The inclination was one to hide in, a heat and want that momentarily erased the weight of loss in my chest.

“That is… theatrical,” I observed, watching her eyes, her lips.

She met my gaze. “It’s fitting.”

“Then Reckoning she shall be.”

FIVE

The Red Company

BENEDICT

My first challenge, after enlisting a company of miscreants to help me steal The Red Tempest from beneath the eyes of the Aeadine Royal Navy and establishing myself as captain, had been to choose my officers.

My options had been sparse. The majority of the original Mereish crew were uncooperative, and I elected to maroon them on a passing cay. That left me with the embittered Aeadine Naval dregs I had found in an Anchorage tavern and convinced to join my piratical enterprise—formerly pressed men and women eager for escape, and a smattering of habitual renegades who had nothing better to do. They were a rough lot, but I was, if nothing else, persuasive.

Now, I surveyed my assembled officers at the table in the main cabin. My first officer, the former Aeadine fourth lieutenant Ms. Olles, sat by my side. She was as northern as they came, having been born within a stone’s throw of the Stormwall. She had the weathered brown skin to prove it, eyes deeply lined from smiling, and an accent that bordered on Mereish.

My second officer had died in a brawl not a week after his election, and his replacement was one Mr. Wuthy. Wuthy was a small man, pale-skinned and graced with the passive, companionable disposition of an aged dog. There was little danger of him following his predecessor’s example, but he was experienced, and well trusted among the crew.

There were others, of course—the bosun, carpenter, gunner and so forth. In total a dozen men and women sat with me over a meal of fish, potatoes and a sauce with a remarkable lack of flavor. Grant and Jessin Faucher were present too, the latter sitting at the opposite end of the table and eating with reserve and gentility.

“We need a cook,” Olles informed me, shoving her empty plate away from her and sitting back. “A Sooth and a cook.”

“And musicians,” said Wuthy, stabbing a slice of potato and popping it into his mouth.

“What happened to the Mereish musicians?” The gunner, pale blond and clean-shaven Hashaw, demanded. “Thought we kept those.”

Wuthy shook his head. “We kept the fiddler, but she’s in poor spirits and poorer health.”

“A Sooth and a cook are of far greater priority,” Olles interjected.

“Your people killed my cook,” Faucher informed us, taking a piece of fish onto his fork. “He was excellent.”

I ignored the exchange and forced myself to eat without reaction, though I too wished my countryfolk had been more discriminate with their musketballs.

“Musicians are vital,” Wuthy pressed. “For morale, for dancing, for the constitution. Neglect these, and we’ll have mutiny on our hands, mark me.”

“Mutiny is no concern,” I said, sitting straighter in my chair and taking a sip of wine. “And if the crew thinks to, they will learn what it is to sail under a Magni Captain.”

There was a span of quiet, into which Ms. Olles finally gave an unconvincing nod and drained her cup.

“Why this concern?” I asked, glancing between the bosun and Wuthy, both of whom spent a great deal of their time playing cards below decks. “The crew have the prospect of ample prize moneys; they are fed and free of the Navy. Why such concern?”

Wuthy twisted his mouth about in thought and sucked his teeth with an audible snick. “They are restless, unsure of you and their future. They have yet to see prize money, while if they’d remained behind, they’d certainly have seen a cut from the battle by now. They speak of time ashore.”

“Both will come,” I frowned. I had been tactful with my Magni influence upon the crew thus far, other than that momentary loss of control in Port Sen. Perhaps I should have been more attentive.

“Several crew went missing in Sen,” the bosun, Kapper, said. He was a former pressed Navy man, and had a perpetually sullen squint to his eyes. “We cannot afford to lose more. We’ve a hundred guns and not enough hands to use them.”