THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ – Complete 16 Book Collection (Fantasy Classics Series) E-Book

L. Frank Baum

1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

In "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: Complete 16 Book Collection," L. Frank Baum crafts a vivid, enchanting narrative that explores themes of friendship, courage, and self-discovery through the whimsical lens of fantasy. This comprehensive collection showcases Baum's unique blend of imaginative storytelling and a rich narrative style that combines humor and moral lessons. Set against the backdrop of the fantastical Land of Oz, the series captivates readers with its memorable characters'—including the resourceful Dorothy, the lovable Scarecrow, and the earnest Tin Woodman'—each representing essential human traits on their quest for personal fulfillment. Baum's inventive use of language and allegorical elements situates the texts within the broader context of early 20th-century American literature, celebrating both individuality and collective resilience. L. Frank Baum, a leading figure in children's literature, was inspired by his experiences and the socio-political landscape of his time to create the magical world of Oz. His background in theater and journalism informed his storytelling, enabling him to convey rich narratives imbued with creativity and social commentary. Baum's vision was not only to entertain but also to engage young readers in thoughts of introspection and moral growth, reflecting the optimism of an era that sought to empower the individual. This extraordinary collection is a must-read for both children and adults alike, offering timeless lessons wrapped in enchanting tales. Readers will find themselves transported to a world of imagination, where every adventure invokes curiosity and wonder. Perfect for lovers of fantasy and anyone seeking to revisit the joys of their childhood, Baum's work stands as a testament to the power of dreams and the importance of believing in oneself. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A comprehensive Introduction outlines these selected works' unifying features, themes, or stylistic evolutions. - The Author Biography highlights personal milestones and literary influences that shape the entire body of writing. - A Historical Context section situates the works in their broader era—social currents, cultural trends, and key events that underpin their creation. - A concise Synopsis (Selection) offers an accessible overview of the included texts, helping readers navigate plotlines and main ideas without revealing critical twists. - A unified Analysis examines recurring motifs and stylistic hallmarks across the collection, tying the stories together while spotlighting the different work's strengths. - Reflection questions inspire deeper contemplation of the author's overarching message, inviting readers to draw connections among different texts and relate them to modern contexts. - Lastly, our hand‐picked Memorable Quotes distill pivotal lines and turning points, serving as touchstones for the collection's central themes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ – Complete 16 Book Collection (Fantasy Classics Series)

Table of Contents

Introduction

THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ – Complete 16 Book Collection (Fantasy Classics Series) assembles, in a single compass, L. Frank Baum’s entire Oz cycle authored by him: fourteen full-length novels accompanied by two shorter companion pieces. Conceived for continuous reading yet hospitable to newcomers, the set presents the whole imaginative arc of Oz as Baum developed it over successive volumes. Bringing these works together underscores their cumulative design: a self-consistent fairyland whose history, customs, and friendships deepen from book to book. The collection’s purpose is preservation and clarity, offering readers the complete primary corpus of Baum’s Oz fiction in one place, readable either sequentially or selectively.

While the heart of this collection is narrative fiction in the form of novels, it also includes shorter tales that distill Baum’s enchantments into briefer episodes. Little Wizard Stories of Oz offers concise adventures crafted for younger readers, showcasing familiar characters in compact form. The Woggle-Bug Book is a comic offshoot centered on one of Baum’s most whimsical creations, extending the universe in a playful key. Together these varied text types—novels and short stories, expansive quests and miniature capers—demonstrate Baum’s versatility within a single mythos, and they give the collection a rhythm that alternates breadth with immediacy without straying beyond the bounds of Oz.

Across the set, unifying themes recur with inviting clarity. Journeys lead not only across marvelous landscapes but toward self-knowledge and mutual reliance. Communities form through kindness, hospitality, and cooperation, while authority is imagined less as coercion than as stewardship and care. Magic serves wonder rather than menace, and even formidable obstacles often yield to courtesy, cleverness, and perseverance. The series celebrates friendship across difference—straw and tin, flesh and clockwork, fairy and human—affirming dignity in varied forms of being. These moral and imaginative commitments give the collection coherence: each book entertains in its own way, yet all point toward courage tempered by compassion.

Stylistically, Baum favors plainspoken narration enlivened by sparkling invention. His chapters move briskly, guided by dialogue that is frank, humorous, and hospitable to young readers without condescension. Neologisms, playful names, and matter-of-fact descriptions of impossible things create a comic deadpan that feels both modern and timeless. Episodes often unfold with theatrical clarity—scenes, entrances, ensembles—reflecting Baum’s instinct for staging and spectacle. Gentle satire peeks through in caricatured officials or topsy-turvy customs, yet the tone remains genial, preferring amusement to scold. The result is a distinctive voice: lucid, generous, and confident that readers can navigate marvels by common sense and good will.

World-building is the series’ abiding achievement. Oz and its neighboring realms possess consistent geography, customs, and magical laws that readers come to recognize: named countries with their own colors and characters, and routes that return in later volumes. Recurring figures reappear in fresh combinations, weaving continuity without closing off discovery. Each book opens a new district, introduces new companions, or reframes a familiar citizen’s role, so the setting accumulates history even as it remains cheerful and accessible. The collection shows how Baum turned a single journey into a sustained mythology, inviting readers to inhabit a living, growing place rather than a one-time destination.

These works occupy a central place in the development of American children’s literature. Baum fashioned a homegrown fairy tale tradition that draws on folklore’s ease while favoring practical humor, democratic manners, and a forward-looking optimism. The first novel established a durable premise that subsequent books broadened without exhausting. The series’ interplay of fantasy and everyday resourcefulness has influenced generations of storytellers, while its images—emerald cities, yellow roads, ingenious companions—have become part of cultural shorthand. Taken together, the sixteen books exemplify how a popular narrative can balance continuity and surprise, speaking freshly to new readers while honoring the expectations of faithful ones.

Leadership, justice, and belonging recur as softly insistent concerns. Rulers earn affection through fairness rather than force; communities organize around shared joy rather than fear. The books repeatedly suggest that wisdom may be found in unlikely forms and that strength is most valuable when it protects the weak. Yet this is no treatise; Baum’s ethics are carried by jokes, banter, and cooperative problem-solving. The series resists cynicism, modeling how differences become assets when friends listen and act together. As a body, the collection defines a civic fairyland—an imaginative laboratory where kindness has practical effects and imagination itself becomes a social good.

Read in sequence, the volumes reveal Baum’s evolving craft and expanding ambitions. Early installments pivot on the astonishment of first encounters; later ones take pleasure in governance, festivals, and the maintenance of a remarkable commonwealth. The shorter pieces distill the atmosphere of the longer books, offering entry points for younger readers and interludes for those already acquainted with Oz. Across the series, Baum responds to an enthusiastic readership by revisiting beloved figures while continually devising new terrains and customs. The collection, therefore, is also a record of literary growth: a sustained conversation between an author, his characters, and their audience.

The narrative architecture encourages multiple approaches. One may begin with the inaugural journey into Oz and proceed through the sequence as the realm’s map and society widen. Alternatively, readers may dip into volumes that focus on particular companions or districts, since each novel clarifies its premise and welcomes independent reading. The inclusion of Little Wizard Stories of Oz permits brief visits that still feel complete, while The Woggle-Bug Book provides a playful variation on the series’ comic logic. However approached, the collection offers a full panorama, from the first crossing into Oz to the later volumes’ confident maturity.

Characterization is both emblematic and lively. Figures associated with singular traits—brains, heart, courage, precision, patience—are drawn with affectionate nuance, allowing symbolic ideas to converse and grow. Human children and fairy rulers meet on equal footing, demonstrating that authority can be personal rather than remote. Antagonists and obstacles tend toward ingenuity rather than terror; contests are staged to showcase wit, cooperation, and moral determination. The companionship that forms among travelers—some made of straw or tin, some mechanical, some royal, some rural—becomes the series’ enduring warmth. The collection thus explores personhood in varied guises, inviting readers to admire difference without fear.

Baum’s language favors clarity, repetition for emphasis, and lightly comic understatement. He names things with cheerful exactness, trusting readers to accept wonders when described plainly. Color motifs and directional journeys provide mnemonic anchors, while feasts, games, and ceremonies supply recurring patterns of communal joy. The humor tends to be kind, the surprises proportional to the world’s rules, and the marvels narrated as if they were only natural. This stylistic economy helps the books remain readable aloud and welcoming to independent readers. In aggregate, the prose produces a steady radiance: bright enough to delight, steady enough to reassure.

Assembled here, the sixteen works form a complete portrait of Baum’s Oz: its arrival, growth, daily life, and resilient cheer. The collection’s value lies in its wholeness. It preserves the continuity of characters and customs across novels, while also honoring the short forms that broadened the audience and enriched the play of tones. Readers new to Oz will find a clear path into a classic landscape; returning travelers will discover how harmoniously the parts converse when read together. This is a treasury of sustained imagination, a unified cycle whose hospitality and good sense continue to welcome readers of every age.

Author Biography

L. Frank Baum (1856–1919) was an American author, editor, and theatrical innovator whose most enduring creation is the land of Oz. Writing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he helped define a distinctly American fairy tale tradition—optimistic, humorous, and grounded in everyday speech. Trained by experience rather than formal literary institutions, he moved among journalism, retail, stage, and early cinema before finding lasting success in children’s books. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz quickly made him a household name, and its sequels, plays, and later screen adaptations cemented his reputation as a foundational figure in popular fantasy and juvenile literature.

Baum grew up in upstate New York and was largely educated at home. He showed an early fascination with printing and amateur publishing, skills that would support a later career in newspapers and magazines. A brief stint at a military academy did not suit him, and he pursued the theatrical and entrepreneurial interests that kept drawing his attention. He also bred fancy poultry and wrote practically about it, an early sign of his comfort with nonfiction as well as storytelling. His reading included classic fairy tales and contemporary children’s literature, and he aspired to shape those traditions for American audiences without imitating European models.

Before literary success, Baum tried a variety of livelihoods: traveling salesperson, actor and manager in small theatrical companies, and proprietor of a general store on the northern Plains. Economic setbacks pushed him into journalism, where he edited a local paper and honed a clear, accessible prose style. After relocating to Chicago in the mid-1890s, he wrote for newspapers and trade publications, including a magazine devoted to window display. His first children’s titles followed: Mother Goose in Prose and Father Goose: His Book, the latter an unexpected bestseller. Collaborations with illustrator W. W. Denslow refined his approach to rhythmic verse and fanciful, character-driven storytelling.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz appeared in 1900, pairing Baum’s plainspoken narration with Denslow’s bold art to reimagine the fairy tale as an American journey. An immensely popular stage adaptation in the early 1900s broadened its reach, and Baum expanded the series almost annually for the next two decades. Illustrator John R. Neill became the primary visual interpreter of the sequels, which developed Oz into a coherent, comic, and gently satirical world. The books foregrounded resourceful girls and women alongside iconic figures like the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman. Critics and educators recognized the series for its inventiveness, humor, and approachable, colloquial style.

Beyond Oz, Baum wrote widely across genres. The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus and Queen Zixi of Ix offered alternative mythmaking and fairyland satire. Under well-documented pseudonyms, he produced popular series fiction: as Edith Van Dyne he issued the Aunt Jane’s Nieces books; as Floyd Akers he wrote the Boy Fortune Hunters adventures; as Laura Bancroft he created Twinkle and Chubbins; and as Schuyler Staunton he published adult romances and adventures. Ever entrepreneurial, he experimented with multimedia storytelling through The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays and helped found the Oz Film Manufacturing Company in the mid-1910s, producing silent features that, despite creative ambition, struggled commercially.

Baum’s social views were complex and, at times, troubling. He lived in a household where women’s rights were actively discussed, and he publicly supported woman suffrage; his fiction frequently centers capable girls and benevolent female leaders. Yet, as a South Dakota newspaper editor in the early 1890s, he wrote editorials about Native Americans that advocated violent, dehumanizing policies in the wake of the Wounded Knee massacre—views now unequivocally condemned. Readers and scholars continue to grapple with this contradiction: humanitarian currents and egalitarian fantasies in his children’s books coexist with documented, harmful rhetoric in his journalism, a tension that complicates assessments of his legacy.

In his later years Baum settled in Southern California, continued the Oz series, and pursued film projects while managing recurring health problems. Several late Oz volumes appeared during the 1910s, with additional titles published posthumously, ensuring the continuity of the saga he had popularized. His influence reverberated widely: the 1939 MGM film adaptation amplified Oz’s cultural presence, while his books have remained in print, inspiring sequels, reinterpretations, and scholarly study. Today he is remembered for establishing a distinctly American mode of children’s fantasy—bright, democratic, and theatrical—whose imaginative geography, gentle satire, and emphasis on courage and compassion continue to engage new generations of readers.

Historical Context

L. Frank Baum (1856–1919) wrote the Oz books across a period of accelerated American change, from the Gilded Age into the Progressive Era and through the First World War. Born in Chittenango, New York, and raised amid post–Civil War industrial expansion, he experienced the rise of railroads, urbanization, and national mass culture. His career meandered through acting, playwriting, journalism, and retail before stabilizing in children’s literature. The sixteen Oz works in this collection, published between 1900 and 1920, reflect those shifts: they mingle frontier myth and metropolitan spectacle, skepticism about harsh economic realities and a countervailing utopian optimism, all filtered through a playful, distinctly American fairy-tale idiom.

Baum’s years on the northern Plains (Aberdeen, South Dakota, 1888–1891) coincided with agrarian unrest and the Populist movement. His Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer editorials in 1890–1891, written in the aftermath of the Wounded Knee massacre, included grievously racist calls against the Sioux—views rightly condemned today. The 1890s also brought the currency debates (gold versus silver), the Panic of 1893, and the 1896 Bryan–McKinley election, which shaped public discourse about money, debt, and power. While the Oz narratives are not reducible to political allegory, their recurrent imagery of silver shoes, yellow brick roads, and embattled farmers resonated with readers living through economic volatility and regional tensions.

Chicago, where Baum settled in the 1890s, positioned him at the center of new cultural industries. The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition—the “White City”—popularized City Beautiful aesthetics, electric illumination, and monumental spectacle. Chicago’s printers and publishers, including the George M. Hill Company, enabled the lavish color production of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), illustrated by W. W. Denslow with integrated color plates and pictorial capitals. That visual modernity paralleled the books’ embrace of a brisk, American vernacular. Chicago’s department stores, amusement parks, and theaters furnished a language of display and wonder that Baum transposed into the Emerald City and its pageantry across multiple volumes.

The 1902–1903 stage musical The Wizard of Oz, produced by Fred R. Hamlin and staged by Julian Mitchell, toured widely, enhancing the series’ profile. Anna Laughlin played Dorothy; vaudeville stars David Montgomery and Fred Stone redefined the Tin Woodman and the Scarecrow as comic partners, influencing Baum’s later ensemble dynamics. Popular tunes, topical jokes, and spectacular scenery tied Oz to the era’s commercial theater culture. This success sparked merchandising, newspaper features, and spinoffs that linked prose, performance, and publicity. The appetite for playful side characters and episodic adventures, seen later across the series, was strengthened by the musical’s rhythms and its audience’s tastes.

After Baum and Denslow parted following disputes over credits and royalties, John R. Neill became the principal Oz illustrator beginning with The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904). Neill’s sinuous Art Nouveau line, crisp black-and-white work, and later full-color plates established a visual identity spanning most subsequent titles. Publishers also shifted: after Hill went bankrupt, Reilly & Britton (founded 1902, later Reilly & Lee, 1919) built the Oz series into a reliable annual offering for the holiday market. Neill’s endpaper maps in Tik-Tok of Oz (1914) codified the geography of Oz and its neighbors, reinforcing the sense of a coherent secondary world across multiple books.

The Progressive Era’s child-centered reforms—kindergartens, play advocacy, and child-labor campaigns—nurtured a new literature of enjoyment rather than admonition. Baum’s 1900 preface openly rejected grim moralism, promising a “modernized fairy tale” free of gratuitous terror. His family ties to suffrage leader Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826–1898), who lived with the Baums in the 1890s, informed his depiction of capable girls and women—Dorothy, Ozma, Glinda—exercising leadership without apology. The women’s rights movement, which culminated in the Nineteenth Amendment (1920), frames the series’ many female rulers, soldiers, and intellectuals. Across volumes, girl protagonists act decisively, not as exceptions but as norms within a reimagined civic order.

Late nineteenth-century Americans engaged enthusiastically with spiritual and occult currents, from Spiritualism to Theosophy. Baum wrote sympathetically about Theosophy in the early 1890s, appreciating its universalist rhetoric and interest in unseen forces. Without preaching doctrine, the Oz books echo a gentle metaphysical openness: magic coexists with everyday pragmatism; benevolent power is exercised with restraint; transformation is common but seldom punitive. These motifs mirror contemporary efforts to reconcile scientific modernity with a hunger for wonder. Oz’s magic tends to be regulated, documented, and even bureaucratized, inviting readers to imagine a cosmos both orderly and enchanted—an ethos sustained across the collection’s successive adventures.

Baum’s immersion in consumer spectacle shaped his narrative and visual sensibilities. He edited The Show Window magazine (from 1897) and wrote The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors (1900), advocating theatrical display in retail. The Oz books frequently stage entrances, parades, and pageants, mirroring department-store windows and world’s fair midways. The series’ design—colored inks, decorative borders, and showy bindings—treated books as objects of desire, encouraging collection and gift-giving. Reilly & Britton cultivated a brand through uniform formats, sequels, and offshoots like Little Wizard Stories of Oz (1913), integrating literature, illustration, and marketing in a manner emblematic of early twentieth-century consumer culture.

American geography—plains, prairies, and new metropolises—grounds Oz’s imaginative departures. The Kansas cyclone that initiates the saga recalls Midwestern storms, rail-linked migrations, and farm vulnerability. As Baum aged, he moved west again, settling at “Ozcot,” his home in Hollywood-adjacent Glendale, California, by 1910–1911. There he wrote many later installments while tending gardens and observing the nascent movie industry. The westering arc of his life mirrors the books’ recurrent crossings between settled homes and marvelous realms. Oz functions as a stable refuge contrasted with precarious borderlands and disaster-prone America, a pattern that became especially salient as readers weathered panics, foreclosures, and the uncertainties of modernization.

Cinema’s rise provided Baum with both opportunity and risk. In 1908 he toured a multimedia lecture, The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays, blending films and hand-colored slides; its costs contributed to financial strain. In 1914 he founded the Oz Film Manufacturing Company in Los Angeles, producing The Patchwork Girl of Oz, His Majesty, the Scarecrow of Oz (later retitled), and The Magic Cloak of Oz, along with The Last Egyptian. Competition, distribution hurdles, and uneven reception curtailed the venture, yet the films deepened the series’ cross-media presence. The interplay between page and screen reinforced Oz as a shared visual vocabulary, feeding back into book illustration and promotion.

Technological modernity pervades the series. Mechanical marvels like Tik-Tok, the clockwork man introduced in prose and onscreen, resonate with contemporaneous automation and the Ford assembly line (1913). Airships, phonographs, wireless experiments, and electrification were reshaping daily life; Baum translated such novelties into a whimsical technological idiom. Travel into and out of Oz often occurs through quasi-scientific mishaps—cyclones, earthquakes, and subterranean fissures—rather than purely mystical portals. This “rationalized enchantment” aligns with the era’s fascination with gadgets and systems while preserving the charm of old-world fairy lore, a balance sustained across titles from Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz to Tik-Tok of Oz.

World War I (1914–1918) cast a long shadow over the later books, though Baum avoided battlefield realism. Ozma’s realm increasingly embodies a pacific utopia: money abolished, hunger unknown, and armies largely ceremonial—a motif visible by The Emerald City of Oz (1910) and reiterated thereafter. The series’ conflicts typically end through cleverness, mercy, or absorption into a just commonwealth rather than annihilation. Works issued during the war years—The Scarecrow of Oz (1915), Rinkitink in Oz (1916), The Lost Princess of Oz (1917), and The Tin Woodman of Oz (1918)—thus offered readers escapist stability while quietly modeling nonviolent governance and communal problem-solving amid global turmoil.

Debates about American empire after 1898—Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines—shaped conversations about sovereignty and benevolent rule. Oz’s political geography, with its protective borders and constellation of neighboring countries, dramatizes encounters between self-governing peoples, meddling rulers, and reluctant conquerors. The series privileges voluntary allegiance, hospitality, and treaties over annexation by force. Characters repeatedly cross cultural lines, learn languages, and negotiate truces, suggesting an alternative to imperial domination. While not free of period stereotypes, these books consistently imagine a plural commonwealth bound by consent and mutual aid. That cosmopolitan spirit threads through volumes from The Road to Oz to Glinda of Oz.

Children’s publishing was globalizing. Contemporary with E. Nesbit in Britain, J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (stage 1904, novel 1911), and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911), Baum helped define an American mode: brisk, comic, serial, and democratic. Correspondence from child readers pressed him for continuations; after announcing an end with The Emerald City of Oz (1910), he returned with Tik-Tok of Oz (1914) and annual volumes thereafter. The serial model fit Reilly & Britton’s business plan and libraries’ growing juvenile sections. Oz’s continuity—recurring characters, maps, and institutions—rewarded loyalty, while new gateways welcomed first-time readers, a balance central to the collection’s enduring cohesion.

Financial cycles punctuated Baum’s career. The Panic of 1907 and recurring farm foreclosures informed storylines about debt, threatened homesteads, and the appeal of a moneyless sanctuary. In The Emerald City of Oz, Aunt Em and Uncle Henry’s impending bankruptcy pushes the family toward permanent settlement in Oz—a fantasy of economic immunity that readers in 1910 would have recognized as wish fulfillment. Baum himself faced insolvency, culminating in bankruptcy proceedings in 1911. The establishment of the Federal Reserve (1913) sought to stabilize such panics even as popular literature continued to explore anxiety about credit, scarcity, and security—concerns refracted playfully across multiple Oz adventures.

The series’ material culture amplified its reach. Uniform bindings, decorative stamping, and Neill’s lucid plates made the books prized objects for households and libraries. After Baum’s death in Hollywood on 6 May 1919, The Magic of Oz appeared that year; Glinda of Oz followed posthumously in 1920 from Reilly & Lee (the firm’s new name after 1919). Later adaptations—notably MGM’s 1939 film with its Technicolor palette and ruby slippers (silver in the 1900 novel)—reshaped public memory but postdate Baum’s authorship. The books themselves, however, set the template: a federated fairyland, visually codified, narratively open-ended, and profoundly embedded in American print and performance economies.

Across all sixteen works, Oz absorbs and reworks the historical energies of 1890–1920 America: Populist-era money anxieties; City Beautiful spectacle; Progressive child-centered education and women’s rights; occult curiosity; consumer display; mechanization; cinematic experimentation; wartime pacifism; and debates over sovereignty. Names and institutions—Matilda Joslyn Gage, the 1893 World’s Fair, George M. Hill, Reilly & Britton/Reilly & Lee, W. W. Denslow, John R. Neill, the Oz Film Manufacturing Company—anchor the series to its moment. Yet the books convert those particulars into a durable myth of civic friendship, inventive problem-solving, and hospitality, a cultural commons that continues to illuminate the American imagination.

Synopsis (Selection)

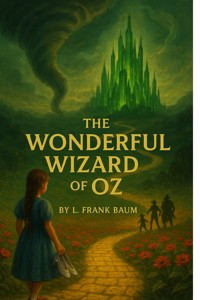

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Carried by a cyclone to the Land of Oz, Dorothy journeys to the Emerald City with a Scarecrow, a Tin Woodman, and a Cowardly Lion, each seeking something they believe they lack. Their road leads through peril and witchcraft toward unexpected discoveries about themselves.

The Marvelous Land of Oz

A boy named Tip flees the witch Mombi with Jack Pumpkinhead and stumbles into a revolt that overturns rule in the Emerald City. With new allies and old friends, the rightful leadership of Oz is restored.

The Woggle-Bug Book

A pun-filled picture-book romp in which the Highly Magnified and Thoroughly Educated Woggle-Bug becomes comically smitten with a flashy plaid dress and chases it through a chain of farcical misadventures.

Ozma of Oz

Shipwrecked in the land of Ev, Dorothy joins Tik-Tok and Billina as Ozma leads a mission to free Ev’s royal family from the Nome King’s enchantments. The rescue forges closer ties between Oz and its neighbors.

Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz

An earthquake drops Dorothy, a boy named Zeb, and others into strange subterranean realms where they reunite with the Wizard. Their perilous trek through bizarre lands ultimately brings them back to Oz.

The Road to Oz

Accompanied by the Shaggy Man, Button-Bright, and Polychrome, Dorothy wanders through whimsical borderlands and curious customs. The journey culminates in a grand celebration in the Emerald City.

The Emerald City of Oz

Dorothy brings Aunt Em and Uncle Henry to live in Oz just as the Nome King rallies allies to invade. Oz’s defenders rely on wit, kindness, and clever magic to protect the realm.

The Patchwork Girl of Oz

After a magical mishap turns loved ones to stone, Ojo sets out with Scraps the Patchwork Girl and other eccentric companions to find rare ingredients for a cure. Their quest spans Oz’s most imaginative corners.

Little Wizard Stories of Oz

Six brief, self-contained tales feature Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, the Cowardly Lion, and more in light adventures that introduce younger readers to Oz.

Tik-Tok of Oz

Betsy Bobbin and her mule Hank join the Shaggy Man and Tik-Tok to free Shaggy’s brother from the Nome King. Comic soldiers, odd kingdoms, and steadfast clockwork heroism drive the rescue.

The Scarecrow of Oz

Trot and Cap’n Bill are swept to a remote corner of Oz where a tyrant threatens Princess Gloria. With the Scarecrow’s help, they outwit enchantments to set the land right.

Rinkitink in Oz

Prince Inga, aided by jovial King Rinkitink, a sardonic goat, and three magic pearls, sets out to reclaim his island and rescue his parents. The quest eventually entangles the implacable Nome King.

The Lost Princess of Oz

Ozma disappears and Oz’s greatest magical tools vanish, prompting a realm-wide search by Dorothy, Glinda, and their friends. Clues lead to a hidden magician whose schemes span Oz.

The Tin Woodman of Oz

Nick Chopper undertakes a sentimental journey to find his first love, traveling with the Scarecrow and a boy named Woot. Their encounters raise tricky questions about identity, memory, and the heart.

The Magic of Oz

A newly discovered transformation magic tempts a restless boy and a dethroned Nome King into plotting against Oz. Meanwhile, friends on a well-meant quest are ensnared by enchantments until order is restored.

Glinda of Oz

Ozma and Dorothy try to mediate a looming war between the Skeezers and the Flatheads but are trapped in an enchanted, submerged city. Glinda organizes a careful rescue that averts conflict and reaffirms Oz’s ideals.

THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ – Complete 16 Book Collection (Fantasy Classics Series)

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Introduction

Folklore, legends, myths and fairy tales have followed childhood through the ages, for every healthy youngster has a wholesome and instinctive love for stories fantastic, marvelous and manifestly unreal. The winged fairies of Grimm and Andersen have brought more happiness to childish hearts than all other human creations.

Yet the old time fairy tale, having served for generations, may now be classed as “historical” in the children’s library; for the time has come for a series of newer “wonder tales” in which the stereotyped genie, dwarf and fairy are eliminated, together with all the horrible and blood-curdling incidents devised by their authors to point a fearsome moral to each tale. Modern education includes morality; therefore the modern child seeks only entertainment in its wonder tales and gladly dispenses with all disagreeable incident.

Having this thought in mind, the story of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” was written solely to please children of today. It aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heartaches and nightmares are left out.

L. Frank Baum Chicago, April, 1900.

1. The Cyclone

Dorothy lived in the midst of the great Kansas prairies, with Uncle Henry, who was a farmer, and Aunt Em, who was the farmer’s wife. Their house was small, for the lumber to build it had to be carried by wagon many miles. There were four walls, a floor and a roof, which made one room; and this room contained a rusty looking cookstove, a cupboard for the dishes, a table, three or four chairs, and the beds. Uncle Henry and Aunt Em had a big bed in one corner, and Dorothy a little bed in another corner. There was no garret at all, and no cellar—except a small hole dug in the ground, called a cyclone cellar, where the family could go in case one of those great whirlwinds arose, mighty enough to crush any building in its path. It was reached by a trap door in the middle of the floor, from which a ladder led down into the small, dark hole.

When Dorothy stood in the doorway and looked around, she could see nothing but the great gray prairie on every side. Not a tree nor a house broke the broad sweep of flat country that reached to the edge of the sky in all directions. The sun had baked the plowed land into a gray mass, with little cracks running through it. Even the grass was not green, for the sun had burned the tops of the long blades until they were the same gray color to be seen everywhere. Once the house had been painted, but the sun blistered the paint and the rains washed it away, and now the house was as dull and gray as everything else.

When Aunt Em came there to live she was a young, pretty wife. The sun and wind had changed her, too. They had taken the sparkle from her eyes and left them a sober gray; they had taken the red from her cheeks and lips, and they were gray also. She was thin and gaunt, and never smiled now. When Dorothy, who was an orphan, first came to her, Aunt Em had been so startled by the child’s laughter that she would scream and press her hand upon her heart whenever Dorothy’s merry voice reached her ears; and she still looked at the little girl with wonder that she could find anything to laugh at.

Uncle Henry never laughed. He worked hard from morning till night and did not know what joy was. He was gray also, from his long beard to his rough boots, and he looked stern and solemn, and rarely spoke.

It was Toto that made Dorothy laugh, and saved her from growing as gray as her other surroundings. Toto was not gray; he was a little black dog, with long silky hair and small black eyes that twinkled merrily on either side of his funny, wee nose. Toto played all day long, and Dorothy played with him, and loved him dearly.

Today, however, they were not playing. Uncle Henry sat upon the doorstep and looked anxiously at the sky, which was even grayer than usual. Dorothy stood in the door with Toto in her arms, and looked at the sky too. Aunt Em was washing the dishes.

From the far north they heard a low wail of the wind, and Uncle Henry and Dorothy could see where the long grass bowed in waves before the coming storm. There now came a sharp whistling in the air from the south, and as they turned their eyes that way they saw ripples in the grass coming from that direction also.

Suddenly Uncle Henry stood up.

“There’s a cyclone coming, Em,” he called to his wife. “I’ll go look after the stock.” Then he ran toward the sheds where the cows and horses were kept.

Aunt Em dropped her work and came to the door. One glance told her of the danger close at hand.

“Quick, Dorothy!” she screamed. “Run for the cellar!”

Toto jumped out of Dorothy’s arms and hid under the bed, and the girl started to get him. Aunt Em, badly frightened, threw open the trap door in the floor and climbed down the ladder into the small, dark hole. Dorothy caught Toto at last and started to follow her aunt. When she was halfway across the room there came a great shriek from the wind, and the house shook so hard that she lost her footing and sat down suddenly upon the floor.

Then a strange thing happened.

The house whirled around two or three times and rose slowly through the air. Dorothy felt as if she were going up in a balloon.

The north and south winds met where the house stood, and made it the exact center of the cyclone. In the middle of a cyclone the air is generally still, but the great pressure of the wind on every side of the house raised it up higher and higher, until it was at the very top of the cyclone; and there it remained and was carried miles and miles away as easily as you could carry a feather.

It was very dark, and the wind howled horribly around her, but Dorothy found she was riding quite easily. After the first few whirls around, and one other time when the house tipped badly, she felt as if she were being rocked gently, like a baby in a cradle.

Toto did not like it. He ran about the room, now here, now there, barking loudly; but Dorothy sat quite still on the floor and waited to see what would happen.

Once Toto got too near the open trap door, and fell in; and at first the little girl thought she had lost him. But soon she saw one of his ears sticking up through the hole, for the strong pressure of the air was keeping him up so that he could not fall. She crept to the hole, caught Toto by the ear, and dragged him into the room again, afterward closing the trap door so that no more accidents could happen.

Hour after hour passed away, and slowly Dorothy got over her fright; but she felt quite lonely, and the wind shrieked so loudly all about her that she nearly became deaf. At first she had wondered if she would be dashed to pieces when the house fell again; but as the hours passed and nothing terrible happened, she stopped worrying and resolved to wait calmly and see what the future would bring. At last she crawled over the swaying floor to her bed, and lay down upon it; and Toto followed and lay down beside her.

In spite of the swaying of the house and the wailing of the wind, Dorothy soon closed her eyes and fell fast asleep.

2. The Council with the Munchkins

She was awakened by a shock, so sudden and severe that if Dorothy had not been lying on the soft bed she might have been hurt. As it was, the jar made her catch her breath and wonder what had happened; and Toto put his cold little nose into her face and whined dismally. Dorothy sat up and noticed that the house was not moving; nor was it dark, for the bright sunshine came in at the window, flooding the little room. She sprang from her bed and with Toto at her heels ran and opened the door.

The little girl gave a cry of amazement and looked about her, her eyes growing bigger and bigger at the wonderful sights she saw.

The cyclone had set the house down very gently—for a cyclone—in the midst of a country of marvelous beauty. There were lovely patches of greensward all about, with stately trees bearing rich and luscious fruits. Banks of gorgeous flowers were on every hand, and birds with rare and brilliant plumage sang and fluttered in the trees and bushes. A little way off was a small brook, rushing and sparkling along between green banks, and murmuring in a voice very grateful to a little girl who had lived so long on the dry, gray prairies.

While she stood looking eagerly at the strange and beautiful sights, she noticed coming toward her a group of the queerest people she had ever seen. They were not as big as the grown folk she had always been used to; but neither were they very small. In fact, they seemed about as tall as Dorothy, who was a well-grown child for her age, although they were, so far as looks go, many years older.

Three were men and one a woman, and all were oddly dressed. They wore round hats that rose to a small point a foot above their heads, with little bells around the brims that tinkled sweetly as they moved. The hats of the men were blue; the little woman’s hat was white, and she wore a white gown that hung in pleats from her shoulders. Over it were sprinkled little stars that glistened in the sun like diamonds. The men were dressed in blue, of the same shade as their hats, and wore well-polished boots with a deep roll of blue at the tops. The men, Dorothy thought, were about as old as Uncle Henry, for two of them had beards. But the little woman was doubtless much older. Her face was covered with wrinkles, her hair was nearly white, and she walked rather stiffly.

When these people drew near the house where Dorothy was standing in the doorway, they paused and whispered among themselves, as if afraid to come farther. But the little old woman walked up to Dorothy, made a low bow and said, in a sweet voice:

“You are welcome, most noble Sorceress, to the land of the Munchkins. We are so grateful to you for having killed the Wicked Witch of the East, and for setting our people free from bondage.”

Dorothy listened to this speech with wonder. What could the little woman possibly mean by calling her a sorceress, and saying she had killed the Wicked Witch of the East? Dorothy was an innocent, harmless little girl, who had been carried by a cyclone many miles from home; and she had never killed anything in all her life.

But the little woman evidently expected her to answer; so Dorothy said, with hesitation, “You are very kind, but there must be some mistake. I have not killed anything.”

“Your house did, anyway,” replied the little old woman, with a laugh, “and that is the same thing. See!” she continued, pointing to the corner of the house. “There are her two feet, still sticking out from under a block of wood.”

Dorothy looked, and gave a little cry of fright. There, indeed, just under the corner of the great beam the house rested on, two feet were sticking out, shod in silver shoes with pointed toes.

“Oh, dear! Oh, dear!” cried Dorothy, clasping her hands together in dismay. “The house must have fallen on her. Whatever shall we do?”

“There is nothing to be done,” said the little woman calmly.

“But who was she?” asked Dorothy.

“She was the Wicked Witch of the East, as I said,” answered the little woman. “She has held all the Munchkins in bondage for many years, making them slave for her night and day. Now they are all set free, and are grateful to you for the favor.”

“Who are the Munchkins?” inquired Dorothy.

“They are the people who live in this land of the East where the Wicked Witch ruled.”

“Are you a Munchkin?” asked Dorothy.

“No, but I am their friend, although I live in the land of the North. When they saw the Witch of the East was dead the Munchkins sent a swift messenger to me, and I came at once. I am the Witch of the North.”

“Oh, gracious!” cried Dorothy. “Are you a real witch?”

“Yes, indeed,” answered the little woman. “But I am a good witch, and the people love me. I am not as powerful as the Wicked Witch was who ruled here, or I should have set the people free myself.”

“But I thought all witches were wicked,” said the girl, who was half frightened at facing a real witch. “Oh, no, that is a great mistake. There were only four witches in all the Land of Oz, and two of them, those who live in the North and the South, are good witches. I know this is true, for I am one of them myself, and cannot be mistaken. Those who dwelt in the East and the West were, indeed, wicked witches; but now that you have killed one of them, there is but one Wicked Witch in all the Land of Oz—the one who lives in the West.”

“But,” said Dorothy, after a moment’s thought, “Aunt Em has told me that the witches were all dead—years and years ago.”

“Who is Aunt Em?” inquired the little old woman.

“She is my aunt who lives in Kansas, where I came from.”

The Witch of the North seemed to think for a time, with her head bowed and her eyes upon the ground. Then she looked up and said, “I do not know where Kansas is, for I have never heard that country mentioned before. But tell me, is it a civilized country?”

“Oh, yes,” replied Dorothy.

“Then that accounts for it. In the civilized countries I believe there are no witches left, nor wizards, nor sorceresses, nor magicians. But, you see, the Land of Oz has never been civilized, for we are cut off from all the rest of the world. Therefore we still have witches and wizards amongst us.”

“Who are the wizards?” asked Dorothy.

“Oz himself is the Great Wizard,” answered the Witch, sinking her voice to a whisper. “He is more powerful than all the rest of us together. He lives in the City of Emeralds.”

Dorothy was going to ask another question, but just then the Munchkins, who had been standing silently by, gave a loud shout and pointed to the corner of the house where the Wicked Witch had been lying.

“What is it?” asked the little old woman, and looked, and began to laugh. The feet of the dead Witch had disappeared entirely, and nothing was left but the silver shoes.

“She was so old,” explained the Witch of the North, “that she dried up quickly in the sun. That is the end of her. But the silver shoes are yours, and you shall have them to wear.” She reached down and picked up the shoes, and after shaking the dust out of them handed them to Dorothy.

“The Witch of the East was proud of those silver shoes,” said one of the Munchkins, “and there is some charm connected with them; but what it is we never knew.”

Dorothy carried the shoes into the house and placed them on the table. Then she came out again to the Munchkins and said:

“I am anxious to get back to my aunt and uncle, for I am sure they will worry about me. Can you help me find my way?”

The Munchkins and the Witch first looked at one another, and then at Dorothy, and then shook their heads.

“At the East, not far from here,” said one, “there is a great desert, and none could live to cross it.”

“It is the same at the South,” said another, “for I have been there and seen it. The South is the country of the Quadlings.”

“I am told,” said the third man, “that it is the same at the West. And that country, where the Winkies live, is ruled by the Wicked Witch of the West, who would make you her slave if you passed her way.”

“The North is my home,” said the old lady, “and at its edge is the same great desert that surrounds this Land of Oz. I’m afraid, my dear, you will have to live with us.”

Dorothy began to sob at this, for she felt lonely among all these strange people. Her tears seemed to grieve the kind-hearted Munchkins, for they immediately took out their handkerchiefs and began to weep also. As for the little old woman, she took off her cap and balanced the point on the end of her nose, while she counted “One, two, three” in a solemn voice. At once the cap changed to a slate, on which was written in big, white chalk marks:

“LET DOROTHY GO TO THE CITY OF EMERALDS”

The little old woman took the slate from her nose, and having read the words on it, asked, “Is your name Dorothy, my dear?”

“Yes,” answered the child, looking up and drying her tears.

“Then you must go to the City of Emeralds. Perhaps Oz will help you.”

“Where is this city?” asked Dorothy.

“It is exactly in the center of the country, and is ruled by Oz, the Great Wizard I told you of.”

“Is he a good man?” inquired the girl anxiously.

“He is a good Wizard. Whether he is a man or not I cannot tell, for I have never seen him.”

“How can I get there?” asked Dorothy.

“You must walk. It is a long journey, through a country that is sometimes pleasant and sometimes dark and terrible. However, I will use all the magic arts I know of to keep you from harm.”

“Won’t you go with me?” pleaded the girl, who had begun to look upon the little old woman as her only friend.

“No, I cannot do that,” she replied, “but I will give you my kiss, and no one will dare injure a person who has been kissed by the Witch of the North.”

She came close to Dorothy and kissed her gently on the forehead. Where her lips touched the girl they left a round, shining mark, as Dorothy found out soon after.

“The road to the City of Emeralds is paved with yellow brick,” said the Witch, “so you cannot miss it. When you get to Oz do not be afraid of him, but tell your story and ask him to help you. Goodbye, my dear.”

The three Munchkins bowed low to her and wished her a pleasant journey, after which they walked away through the trees. The Witch gave Dorothy a friendly little nod, whirled around on her left heel three times, and straightway disappeared, much to the surprise of little Toto, who barked after her loudly enough when she had gone, because he had been afraid even to growl while she stood by.

But Dorothy, knowing her to be a witch, had expected her to disappear in just that way, and was not surprised in the least.

3. How Dorothy Saved the Scarecrow

When Dorothy was left alone she began to feel hungry. So she went to the cupboard and cut herself some bread, which she spread with butter. She gave some to Toto, and taking a pail from the shelf she carried it down to the little brook and filled it with clear, sparkling water. Toto ran over to the trees and began to bark at the birds sitting there. Dorothy went to get him, and saw such delicious fruit hanging from the branches that she gathered some of it, finding it just what she wanted to help out her breakfast.

Then she went back to the house, and having helped herself and Toto to a good drink of the cool, clear water, she set about making ready for the journey to the City of Emeralds.

Dorothy had only one other dress, but that happened to be clean and was hanging on a peg beside her bed. It was gingham, with checks of white and blue; and although the blue was somewhat faded with many washings, it was still a pretty frock. The girl washed herself carefully, dressed herself in the clean gingham, and tied her pink sunbonnet on her head. She took a little basket and filled it with bread from the cupboard, laying a white cloth over the top. Then she looked down at her feet and noticed how old and worn her shoes were.

“They surely will never do for a long journey, Toto,” she said. And Toto looked up into her face with his little black eyes and wagged his tail to show he knew what she meant.

At that moment Dorothy saw lying on the table the silver shoes that had belonged to the Witch of the East.

“I wonder if they will fit me,” she said to Toto. “They would be just the thing to take a long walk in, for they could not wear out.”

She took off her old leather shoes and tried on the silver ones, which fitted her as well as if they had been made for her.

Finally she picked up her basket.

“Come along, Toto,” she said. “We will go to the Emerald City and ask the Great Oz how to get back to Kansas again.”

She closed the door, locked it, and put the key carefully in the pocket of her dress. And so, with Toto trotting along soberly behind her, she started on her journey.

There were several roads near by, but it did not take her long to find the one paved with yellow bricks. Within a short time she was walking briskly toward the Emerald City, her silver shoes tinkling merrily on the hard, yellow road-bed. The sun shone bright and the birds sang sweetly, and Dorothy did not feel nearly so bad as you might think a little girl would who had been suddenly whisked away from her own country and set down in the midst of a strange land.

She was surprised, as she walked along, to see how pretty the country was about her. There were neat fences at the sides of the road, painted a dainty blue color, and beyond them were fields of grain and vegetables in abundance. Evidently the Munchkins were good farmers and able to raise large crops. Once in a while she would pass a house, and the people came out to look at her and bow low as she went by; for everyone knew she had been the means of destroying the Wicked Witch and setting them free from bondage. The houses of the Munchkins were odd-looking dwellings, for each was round, with a big dome for a roof. All were painted blue, for in this country of the East blue was the favorite color.

Toward evening, when Dorothy was tired with her long walk and began to wonder where she should pass the night, she came to a house rather larger than the rest. On the green lawn before it many men and women were dancing. Five little fiddlers played as loudly as possible, and the people were laughing and singing, while a big table near by was loaded with delicious fruits and nuts, pies and cakes, and many other good things to eat.

The people greeted Dorothy kindly, and invited her to supper and to pass the night with them; for this was the home of one of the richest Munchkins in the land, and his friends were gathered with him to celebrate their freedom from the bondage of the Wicked Witch.

Dorothy ate a hearty supper and was waited upon by the rich Munchkin himself, whose name was Boq. Then she sat upon a settee and watched the people dance.

When Boq saw her silver shoes he said, “You must be a great sorceress.”

“Why?” asked the girl.

“Because you wear silver shoes and have killed the Wicked Witch. Besides, you have white in your frock, and only witches and sorceresses wear white.”

“My dress is blue and white checked,” said Dorothy, smoothing out the wrinkles in it.

“It is kind of you to wear that,” said Boq. “Blue is the color of the Munchkins, and white is the witch color. So we know you are a friendly witch.”

Dorothy did not know what to say to this, for all the people seemed to think her a witch, and she knew very well she was only an ordinary little girl who had come by the chance of a cyclone into a strange land.

When she had tired watching the dancing, Boq led her into the house, where he gave her a room with a pretty bed in it. The sheets were made of blue cloth, and Dorothy slept soundly in them till morning, with Toto curled up on the blue rug beside her.

She ate a hearty breakfast, and watched a wee Munchkin baby, who played with Toto and pulled his tail and crowed and laughed in a way that greatly amused Dorothy. Toto was a fine curiosity to all the people, for they had never seen a dog before.

“How far is it to the Emerald City?” the girl asked.

“I do not know,” answered Boq gravely, “for I have never been there. It is better for people to keep away from Oz, unless they have business with him. But it is a long way to the Emerald City, and it will take you many days. The country here is rich and pleasant, but you must pass through rough and dangerous places before you reach the end of your journey.”

This worried Dorothy a little, but she knew that only the Great Oz could help her get to Kansas again, so she bravely resolved not to turn back.

She bade her friends goodbye, and again started along the road of yellow brick. When she had gone several miles she thought she would stop to rest, and so climbed to the top of the fence beside the road and sat down. There was a great cornfield beyond the fence, and not far away she saw a Scarecrow, placed high on a pole to keep the birds from the ripe corn.

Dorothy leaned her chin upon her hand and gazed thoughtfully at the Scarecrow. Its head was a small sack stuffed with straw, with eyes, nose, and mouth painted on it to represent a face. An old, pointed blue hat, that had belonged to some Munchkin, was perched on his head, and the rest of the figure was a blue suit of clothes, worn and faded, which had also been stuffed with straw. On the feet were some old boots with blue tops, such as every man wore in this country, and the figure was raised above the stalks of corn by means of the pole stuck up its back.

While Dorothy was looking earnestly into the queer, painted face of the Scarecrow, she was surprised to see one of the eyes slowly wink at her. She thought she must have been mistaken at first, for none of the scarecrows in Kansas ever wink; but presently the figure nodded its head to her in a friendly way. Then she climbed down from the fence and walked up to it, while Toto ran around the pole and barked.

“Good day,” said the Scarecrow, in a rather husky voice.

“Did you speak?” asked the girl, in wonder.

“Certainly,” answered the Scarecrow. “How do you do?”

“I’m pretty well, thank you,” replied Dorothy politely. “How do you do?”

“I’m not feeling well,” said the Scarecrow, with a smile, “for it is very tedious being perched up here night and day to scare away crows.”

“Can’t you get down?” asked Dorothy.

“No, for this pole is stuck up my back. If you will please take away the pole I shall be greatly obliged to you.”

Dorothy reached up both arms and lifted the figure off the pole, for, being stuffed with straw, it was quite light.

“Thank you very much,” said the Scarecrow, when he had been set down on the ground. “I feel like a new man.”

Dorothy was puzzled at this, for it sounded queer to hear a stuffed man speak, and to see him bow and walk along beside her.

“Who are you?” asked the Scarecrow when he had stretched himself and yawned. “And where are you going?”

“My name is Dorothy,” said the girl, “and I am going to the Emerald City, to ask the Great Oz to send me back to Kansas.”

“Where is the Emerald City?” he inquired. “And who is Oz?”

“Why, don’t you know?” she returned, in surprise.

“No, indeed. I don’t know anything. You see, I am stuffed, so I have no brains at all,” he answered sadly.

“Oh,” said Dorothy, “I’m awfully sorry for you.”

“Do you think,” he asked, “if I go to the Emerald City with you, that Oz would give me some brains?”

“I cannot tell,” she returned, “but you may come with me, if you like. If Oz will not give you any brains you will be no worse off than you are now.”

“That is true,” said the Scarecrow. “You see,” he continued confidentially, “I don’t mind my legs and arms and body being stuffed, because I cannot get hurt. If anyone treads on my toes or sticks a pin into me, it doesn’t matter, for I can’t feel it. But I do not want people to call me a fool, and if my head stays stuffed with straw instead of with brains, as yours is, how am I ever to know anything?”

“I understand how you feel,” said the little girl, who was truly sorry for him. “If you will come with me I’ll ask Oz to do all he can for you.”

“Thank you,” he answered gratefully.

They walked back to the road. Dorothy helped him over the fence, and they started along the path of yellow brick for the Emerald City.

Toto did not like this addition to the party at first. He smelled around the stuffed man as if he suspected there might be a nest of rats in the straw, and he often growled in an unfriendly way at the Scarecrow.

“Don’t mind Toto,” said Dorothy to her new friend. “He never bites.”

“Oh, I’m not afraid,” replied the Scarecrow. “He can’t hurt the straw. Do let me carry that basket for you. I shall not mind it, for I can’t get tired. I’ll tell you a secret,” he continued, as he walked along. “There is only one thing in the world I am afraid of.”

“What is that?” asked Dorothy; “the Munchkin farmer who made you?”

“No,” answered the Scarecrow; “it’s a lighted match.”