THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ – Complete Collection: 16 Novels in One Premium Edition (Fantasy Classics Series) E-Book

L. Frank Baum

1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

L. Frank Baum's "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz 'Äì Complete Collection: 16 Novels in One Premium Edition" explores the enchanting world of Oz through a series of richly woven narratives that blend fantasy, adventure, and moral allegory. The literary style showcases Baum's imaginative storytelling and childlike wonder, marked by whimsical prose and vibrant characterizations. Set against the backdrop of American socio-cultural dynamics in the early 20th century, the series invites readers to traverse a magical landscape filled with profound themes of friendship, self-discovery, and the quest for identity, capturing the zeitgeist of Baum's era while still resonating with contemporary audiences. Born in 1856, L. Frank Baum's upbringing in a family that valued creativity and storytelling undoubtedly influenced his literary voice. His experiences as a traveling salesman and playwright enriched his understanding of narrative structure while instilling a belief in the transformative power of happiness and imagination. Baum's commitment to children'Äôs literature, coupled with his desire to create tales that inspired and entertained, culminated in the beloved Oz series, which continues to spark the imagination of readers young and old. I highly recommend this collection to anyone intrigued by fantasy literature or seeking to revisit the foundational tales of childhood. Baum's engaging prose and the series' delightful illustrations offer a timeless journey that transcends age, providing both entertainment and insightful life lessons. Dive into the magical world of Oz and discover the enduring allure of Baum's extraordinary vision.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ – Complete Collection: 16 Novels in One Premium Edition (Fantasy Classics Series)

Table of Contents

Introduction

This premium single-author collection gathers sixteen Oz works by L. Frank Baum, bringing together the complete cycle of Oz novels alongside two companion volumes in one continuous reading experience. It presents the arc that begins with a Kansas child’s unexpected arrival in a marvelous land and extends through a rich sequence of journeys, encounters, and returns. By assembling these works as a whole, the edition allows readers to appreciate the breadth of Baum’s invention, the coherence of his imagined world, and the evolving interplay of recurring characters and places that define his landmark achievement in children’s fantasy and American storytelling.

While the heart of this volume is narrative fiction, it includes a range of text types that reveal Baum’s versatility within his Oz creation. The collection comprises all fourteen Oz novels and two shorter companion works: one a set of brief, self-contained tales designed for younger readers, the other a lively, comic prose spin-off featuring a familiar figure. Together, they demonstrate how Baum adapted his material for different readerships and formats while keeping the tone, setting, and narrative logic consistent. The emphasis remains squarely on prose storytelling, with accessible language and episodes that welcome both independent reading and shared, aloud enjoyment.

The series began in 1900 and continued through 1920, expanding from a single modern fairy tale into a sustained cycle at readers’ request. Across these years, Baum refined the geography, customs, and narrative rhythms of Oz, exploring new corners of the map while reuniting audiences with favorite companions. In bringing together works from the full span of his authorship, this edition highlights the historical development of the series: the early establishment of its rules, the mid-series deepening of character networks, and the later volumes’ confident command of the world’s possibilities. The result is a panoramic view of an enduring imaginative enterprise.

Read as a whole, these works reveal a meticulously coherent secondary world, bound by gentle laws of magic, clear moral intuitions, and a distinctive comic sense. The Emerald City, outlying realms, and neighboring lands form a connected stage on which varied travelers, rulers, and odd mechanical or enchanted beings meet and part. Recurring friends enrich the continuity, while new protagonists periodically take center stage, keeping the narrative fresh without sacrificing familiarity. Baum’s design balances novelty and return, letting each book stand on its own yet reward attentive reading of the entire cycle through echoes, callbacks, and evolving relationships.

Certain themes recur with admirable clarity. Friendship and cooperation repeatedly prove more powerful than force. Courage often appears in unassuming forms, and resourcefulness outstrips brute strength. The stories prize kindness, loyalty, and a welcoming attitude toward difference, inviting readers to see that oddity is often a virtue. Home is cherished, yet curiosity and open-hearted adventure are celebrated as civilizing forces. Authority is tested by experience, not inherited prestige. The books affirm that imagination and moral steadiness can transform peril into discovery, and that communities flourish when they value each member’s peculiar gifts, however humble or unconventional they may seem.

Stylistically, Baum writes with clarity and economy, favoring brisk episodes, crisp dialogue, and unfussy description that places marvelous incidents within a matter-of-fact narrative voice. Humor runs throughout: playful puns, literal-minded jokes, and sly turns of logic punctuate the action. He excels at inventing creatures, contraptions, and customs that are both surprising and coherent, lending plausibility to the implausible. The episodic travel structure supports set-piece encounters that feel theatrical in their staging and timing, yet the momentum remains propulsive. Above all, the tone is humane, refusing cynicism while acknowledging foibles, and thereby sustaining a welcoming atmosphere across successive adventures.

A gentle current of social observation animates the series. Pretension, empty spectacle, and sham authority are regularly unmasked, while leadership is shown to depend on empathy, steadiness, and service. Baum gives special prominence to capable girls and women—adventurers, princesses, and sorceresses—whose intelligent kindness guides communities and resolves crises. The books value education without pedantry, courage without cruelty, and order without rigidity. By couching these insights within fairylands and capers, Baum avoids sermonizing; instead, he models ethical action through choice and consequence, inviting readers to recognize dignity in themselves and others while delighting in the merriment of make-believe.

Variation within unity keeps the cycle invigorating. Some volumes are expansive travelogues that survey new territories; others concentrate on a rescue, a quest, or a reunion. Comic energy rises in certain entries, while others emphasize wonder, craft, or quiet domestic warmth. Particular books introduce memorable figures—clockwork companions, animated patchwork, royal visitors—each adding textures of humor or pathos. The shorter tales offer swift, independent adventures ideal for younger audiences or brief readings, and the playful spin-off showcases Baum’s relish for wordplay and eccentricity. Across these modes, the spirit remains constant: curiosity rewarded, cooperation tested, and imagination made tangible.

The works are designed to be hospitable at any point of entry. Each narrative supplies the orientation needed for newcomers, while returning readers find layered pleasures in recurring details, evolving friendships, and the steady enrichment of Oz’s landscape. This dual accessibility is central to the series’ longevity: it encourages exploration without anxiety about sequence, yet it also repays a complete reading with a fuller sense of tonal shading and thematic accumulation. In this edition, the continuity of characters and places becomes especially vivid, allowing the interplay among volumes to surface naturally as the journey unfolds.

As a whole, these books helped establish a distinctly American tradition of the fairy tale—rooted in optimism, democratic manners, and practical wit. Their endurance owes much to Baum’s equilibrium of innocence and savvy, his readiness to invite laughter without contempt, and his art of wonder made believable. Generations have found in Oz a refuge for the imagination and a mirror for everyday virtues. The stories travel well across ages: lively enough for children, nimble enough for adults who appreciate craft and satire. Sustained rereading reveals not only invention but also a consistently humane outlook that feels both fresh and familiar.

The scope of this collection is deliberately focused: it assembles all of Baum’s Oz novels together with two closely related companion works, presenting the complete Oz narrative authored by him. It does not attempt to survey his non-Oz fantasies or later continuations by other writers; instead, it concentrates on the primary corpus that established the characters, settings, and narrative principles of Oz. This clarity of focus benefits the reader, preserving a coherent voice and vision across the set while showcasing the series’ internal variety. The result is a comprehensive, single-author portrait of Oz at its source.

Readers approaching these pages for the first time will find an open door to one of literature’s friendliest imagined realms; returning travelers will discover how naturally the stories converse with one another when read together. Gathered in one place, the sequence reveals its generous architecture, its steady humor, and its faith in courage tempered by kindness. The collection’s purpose is simple and inviting: to make a complete journey possible, at one’s own pace, without losing the spontaneity that defines Oz. May these adventures offer delight, companionship, and the confidence that good sense and good hearts can do marvelous things.

Author Biography

American author Lyman Frank Baum (1856–1919) is best known as the creator of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and the subsequent Oz books, a cornerstone of children’s literature in the United States. Writing at the turn of the twentieth century, he helped shift the fairy tale from European forests to an American landscape of prairies, emerald cities, and plucky protagonists. His blend of whimsy, clear prose, and gentle satire appealed to young readers while offering adults a playful critique of modern life. Beyond Oz, he was a prolific storyteller, journalist, and theatrical entrepreneur whose work helped define the possibilities of popular fantasy.

Born in upstate New York, Baum received limited formal schooling and was largely educated at home before attending Peekskill Military Academy for a short time. Early interests in printing and performance led him to publish amateur newspapers and to try his hand on the stage as an actor and playwright. He managed touring companies and wrote melodramas, experiences that sharpened his sense of pacing, comic set pieces, and spectacle. Although these ventures seldom brought lasting security, they shaped his taste for vivid scenes and approachable dialogue. This practical grounding in show business later informed the theatricality and episodic structure of his children’s narratives.

During the late 1880s he moved west to the Dakota Territory, where he ran a shop and edited a small newspaper, the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer. In that role he published two inflammatory editorials about Native Americans in 1890, rhetoric that has been widely condemned and remains a troubling part of his record. After relocating to Chicago in the early 1890s, he turned more fully to writing. Mother Goose in Prose introduced his storytelling to a broader public, and Father Goose, His Book became a notable commercial success. These works established his voice in children’s literature and set the stage for his most famous creation.

In 1900 Baum published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, illustrated by W. W. Denslow, presenting a modern American fairy tale free of heavy moralizing and gruesome punishments. The book was an immediate hit with readers and reviewers, and a popular stage adaptation followed in the early 1900s, bringing the characters to theatrical audiences nationwide. Encouraged by the response, Baum wrote numerous Oz sequels that expanded the geography, cast, and lore of the realm. The series balanced adventure with humor and emphasized resourceful children, especially girls, navigating strange lands with common sense—an approach that helped secure a loyal, intergenerational readership.

Although Oz dominated his reputation, Baum’s imagination ranged widely. He published American Fairy Tales, The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, and Queen Zixi of Ix, along with maritime and island fantasies that introduced characters who later crossed into Oz. To reach different audiences he sometimes wrote under pseudonyms, notably Edith Van Dyne for the Aunt Jane’s Nieces series and Laura Bancroft for short fantasy tales. Across genres he favored light, conversational narration, inventive creatures, and a comic temper that downplayed didacticism. Many stories featured capable young women and collaborative problem-solving, reflecting views on women’s roles that aligned with contemporary suffrage advocacy.

Baum pursued new media eagerly. A touring multimedia program, The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays, sought to combine narration with hand-tinted slides and motion pictures; innovative but costly, it strained his finances. Later, he helped launch the Oz Film Manufacturing Company in California to produce silent fantasies, but the enterprise struggled in a shifting marketplace. He faced periodic financial difficulties, yet continued to write Oz novels for devoted readers. Settling in the Los Angeles area, at a home he called Ozcot, he worked steadily in his final years, revisiting beloved characters and integrating newer figures from his non-Oz fantasies into the expanding saga.

Baum died in 1919, leaving an extensive body of children’s fiction that remained in print and invited continuations by other authors. The 1939 film adaptation of The Wizard of Oz, produced two decades after his death, turned his Kansas-to-Emerald City vision into a global touchstone and revived interest in the books. Today scholars and readers recognize his role in creating an American fairy tale tradition, appreciate his humor and imaginative reach, and debate aspects of his cultural outlook. His support for women’s equality contrasts starkly with his harmful editorials about Native peoples, ensuring that assessments of his legacy remain nuanced.

Historical Context

L. Frank Baum’s Oz oeuvre emerged between 1900 and 1920, a span that aligns with the American Progressive Era, rapid industrialization, and a redefinition of childhood as a protected, imaginative sphere. When The Wonderful Wizard of Oz appeared in Chicago in 1900, it announced itself, in Baum’s own preface, as a “modern fairy tale,” free of the moral severity of earlier didactic works. The ensuing cycle—extending through The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904) to the posthumous Glinda of Oz (1920)—speaks to a culture grappling with modern technology, urban growth, and reformist ideals, while offering children narrative spaces of safety, order, and playful innovation.

Baum’s personal history anchors these books in concrete times and places. Born on 15 May 1856 in Chittenango, New York, he married Maud Gage in 1882, daughter of the suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826–1898). This family milieu, steeped in women’s rights and freethought, informs Oz’s enduring matriarchies—embodied by Ozma and Glinda—across multiple titles, including Ozma of Oz (1907), The Emerald City of Oz (1910), The Lost Princess of Oz (1917), and Glinda of Oz (1920). Baum died on 6 May 1919 in Hollywood, California, having transformed American children’s literature with an invented geography whose rulers and citizens continually reimagine authority, care, and community.

The Great Plains shaped Baum’s sensibility. He lived in Dakota Territory (later South Dakota) from 1888 to 1891, operating Baum’s Bazaar in Aberdeen and editing the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer during the traumatic winter of 1890–91, the period of the Wounded Knee massacre. His editorials—today recognized for their inflammatory calls against Indigenous people—reflect the era’s settler colonial violence. The spare setting of Kansas in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the tornado that initiates Dorothy’s passage, and the attention to agrarian hardship resonate with broader regional experiences. These plains-derived images form a counterpoint to the ornate fantasy of the Emerald City, balancing austerity and abundance.

Chicago provided Baum with a modernist canvas. After moving there in 1891, he witnessed the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, whose electric “White City” suggested the spectacle later echoed in Emerald City vistas. Chicago’s publishing and theater scenes enabled Father Goose (1899) and, with illustrator W. W. Denslow, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). The city also hosted the 1902–04 stage extravaganza The Wizard of Oz, whose vaudevillian tone and new comic business influenced later books, from The Marvelous Land of Oz to The Woggle-Bug Book (1905). Chicago thus mediated between Baum’s journalistic past and the multimedia future of Oz as a national phenomenon.

Shifts in publishers and illustrators mapped onto the series’ evolution. The 1900 debut was issued by the George M. Hill Company (Chicago), which folded in 1902. From 1904, Reilly & Britton (also Chicago; later Reilly & Lee in 1919) became the Oz house, shaping formats, pricing, and annual schedules. The visual language changed too: Denslow’s robust, poster-like color yielded to John R. Neill’s elegant line from The Marvelous Land of Oz forward, defining Oz’s look through The Magic of Oz (1919) and Glinda of Oz (1920). Reilly & Britton’s small-format Little Wizard Stories of Oz (1913) targeted beginner readers, reflecting new market segmentation.

American popular theater was crucial to Oz’s cross-media life. The Wizard of Oz (1902), produced by Fred R. Hamlin and staged by Julian Mitchell, toured nationally, cementing the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman—played by Fred Stone and David C. Montgomery—as comic stars. The craze spawned The Woggle-Bug Book (1905), a picture-book spin-off exploiting a character born onstage. Later, The Tik-Tok Man of Oz (1913), with music by Louis F. Gottschalk, informed the plot and personae of Tik-Tok of Oz (1914). The porous boundary between stage and page helped standardize character traits across the canon, ensuring continuity from Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz to The Scarecrow of Oz.

Early Hollywood amplified—and tested—Oz’s adaptability. After wintering in Coronado, California, in the 1900s, Baum settled at “Ozcot” in Hollywood by 1910–11. He co-founded the Oz Film Manufacturing Company in 1914, producing The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1914), The Magic Cloak (from Queen Zixi of Ix, 1914), and His Majesty, the Scarecrow of Oz (1914). Distribution headwinds and audience expectations doomed the venture by 1915, but the experiment fed back into the books. The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1913) and The Scarecrow of Oz (1915) display cinematic pacing and ensemble casting, while Rinkitink in Oz (1916) adapts an earlier non-Oz romance to the series’ screen-ready continuity.

Baum’s spiritual and intellectual surroundings enriched Oz’s metaphysics. In 1890s Chicago he attended—and reportedly joined—Theosophical circles, an esoteric movement popularized in America by Helena P. Blavatsky and later Annie Besant. Theosophy’s syncretic cosmology, benevolent adepts, and cyclical time resonate in Glinda’s serene power, Ozma’s agelessness, and the non-Christian, ethical magic that structures The Road to Oz (1909), The Emerald City of Oz (1910), and The Magic of Oz (1919). Rather than miracle or doctrine, Oz foregrounds orderly, rule-bound enchantment, reflecting contemporary fascination with unseen forces—magnetism, electricity, and psychology—channeled into a pacific, child-centered utopia.

Economic anxieties of the Gilded Age and Progressive reforms linger behind Oz’s imagery. Debates over bimetallism and the 1893 panic helped generate later interpretations—most influentially Henry M. Littlefield’s 1964 essay—that read the Silver Shoes and Yellow Brick Road in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as allegories of “free silver” and the gold standard. Whether or not Baum intended this, the books repeatedly stage resource politics, from Nome King’s mineral hoards to restorative abundance in The Emerald City of Oz. The series inhabits a culture negotiating trusts, rail expansion, and regulatory ideals, converting material conflicts into ethical tales about fairness, ingenuity, and community.

Children’s publishing professionalized as Baum wrote. Librarians, educators, and magazine editors debated fantasy’s value; some critics favored realism, while others embraced imaginative reading as healthy recreation. Baum explicitly pitched his series against punitive moralism, preferring humor, surprise, and recurrent friends. Seriality—evident from The Marvelous Land of Oz through The Lost Princess of Oz (1917)—mirrored trends in juvenile series fiction and periodical culture. The small-format Little Wizard Stories of Oz (1913) aligned with emergent graded reading markets, while lavish color plates in early volumes catered to gift-book economies. These publishing strategies ensured that Oz reached classrooms, parlors, and circulating libraries across the United States.

Oz thrived within a new consumer culture of branded characters and cross-promotions. Baum’s collaborations yielded songs, sheet music, toys, and games, including a Parker Brothers Woggle-Bug board game (1904). He scripted the newspaper feature Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz (1904–1905), bringing Oz personages into American cities and cementing their serial identities between novels like Ozma of Oz and Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz (1908). Such paratexts created feedback loops: readers arrived at The Road to Oz (1909) and Tik-Tok of Oz (1914) expecting a shared universe with stable lore, while publishers leveraged that consistency for seasonal sales cycles.

Contemporary disasters and discoveries surface within Oz’s plots. Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz opens with a California earthquake, published in 1908 within living memory of the devastating 1906 San Francisco event, and refracts modern fragility through magical rescue. American fascination with polar, desert, and island exploration—heightened by imperial acquisitions in 1898—echoes in the archipelagic adventures of Rinkitink in Oz (1916) and the peripatetic crossings of The Road to Oz. Movement between Kansas, California, and fantastical realms parallels the era’s internal migrations and tourism, linking domestic modernity with enchanted altered states that remain carefully insulated from contemporary geopolitical violence.

Technological imagination saturates the series. The Wizard arrives by hot-air balloon, a nod to nineteenth-century aeronautics; Tik-Tok, appearing from Ozma of Oz onward and central to Tik-Tok of Oz (1914), personifies clockwork automation at a moment when American factories were reorganizing labor around mechanization. The Tin Woodman, who regains his heart without becoming less metallic, reframes machine-human boundaries. Devices like the Magic Picture and Glinda’s Great Book resemble encyclopedic media and telegraphy, rendering information instantaneous but benevolent. Across The Patchwork Girl of Oz and The Tin Woodman of Oz (1918), tools and techniques advance cooperation and craft rather than war, countering industrial-age anxieties.

Oz’s politics reflect progressive and pacifist currents. Female sovereignty under Ozma and the diplomatic authority of Glinda recur from The Marvelous Land of Oz to Glinda of Oz, published the year the Nineteenth Amendment (1920) enfranchised American women. Military satire—such as the hapless armies in The Emerald City of Oz or the comic militias of Oogaboo in Tik-Tok of Oz—lampoons conquest during an era shadowed by imperial wars and, later, World War I. Conflicts resolve through transformation, enchantment, or inclusion; villains become friends, as in The Scarecrow of Oz (1915), or are neutralized without slaughter, aligning fantasy governance with reformist ideals.

Urbanization and immigration reshaped American life, and Oz offers a counter-urban model of cosmopolitan order. The Emerald City’s planned beauty and public hospitality echo City Beautiful ideals visible since 1893 in Chicago. Its color-coded countries—yellow Winkie, blue Munchkin, purple Gillikin, and red Quadling—reimagine difference as aesthetic variety rather than hierarchy, even as the books acknowledge borders, laws, and customs. Characters from disparate backgrounds—Rinkitink’s islanders, the Shaggy Man, or visitors in The Road to Oz—find welcome and function within Oz’s social contract. This idealized metropolis doubles as a child’s city: safe, legible, and endlessly walkable, unlike many contemporary American streets.

Baum’s business fortunes shaped the cycle’s cadence. After declaring The Emerald City of Oz (1910) a finale—he has Oz sealed from outsiders—he resumed with The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1913) amid financial pressures and reader demand, a pattern supported by Reilly & Britton’s annual lists. The Oz Film Manufacturing Company’s failure (1914–1915) deepened those pressures, yet also folded cinematic ideas into The Scarecrow of Oz (1915) and Rinkitink in Oz (1916). Health challenges in the late 1910s coincided with wartime scarcity, but he produced The Lost Princess of Oz (1917), The Tin Woodman of Oz (1918), and The Magic of Oz (1919) before his death.

The Oz canon’s early reception and long afterlife frame these sixteen works. Posthumously, Reilly & Lee continued annual titles with Ruth Plumly Thompson beginning in 1921, while John R. Neill extended the visual idiom he had forged since 1904. The 1939 MGM film would later remap cultural memory—transforming Baum’s Silver Shoes into ruby slippers—but the textual bedrock from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz to Glinda of Oz remains a Progressive Era artifact. It consolidates suffragist legacies, Theosophical speculation, Chicago modernity, and Plains realism into a shared world that helped define American series fiction, franchising, and children’s narrative citizenship.

Synopsis (Selection)

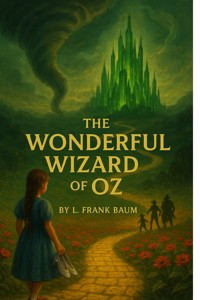

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

After a cyclone carries Dorothy to the Land of Oz, she journeys to the Emerald City with the Scarecrow, Tin Woodman, and Cowardly Lion to ask the Wizard for help returning home. Along the way, they must confront the Wicked Witch of the West and discover their own strengths.

The Marvelous Land of Oz

A boy named Tip flees the witch Mombi and, with companions like Jack Pumpkinhead and the Woggle-Bug, helps the Scarecrow reclaim his throne from General Jinjur. Their quest leads to the rightful restoration of Oz’s monarchy.

The Woggle-Bug Book

A comic picture-book following the Highly Magnified Woggle-Bug’s absurd pursuit of an idealized ‘lady’ from a fashion plate. It strings together pun-filled episodes outside the main Oz continuity.

Ozma of Oz

Shipwrecked in a strange land, Dorothy joins forces with Tik-Tok, Billina, and Princess Ozma to free the royal family of Ev from the Nome King. Their rescue hinges on a perilous guessing game with high stakes.

Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz

After an earthquake drops them into subterranean realms, Dorothy, her cousin Zeb, the Wizard, and their animals face bizarre peoples and perils on their way back to Oz. Ingenuity and a bit of sorcery see them through.

The Road to Oz

Dorothy and Toto wander strange byways with the Shaggy Man, Button-Bright, and Polychrome, meeting curious folk along a meandering route. Their travels culminate in a grand celebration at Ozma’s birthday in the Emerald City.

The Emerald City of Oz

Dorothy brings Aunt Em and Uncle Henry to settle in Oz while the Nome King schemes an invasion. Tours of unusual communities contrast with the mounting threat to the Emerald City.

The Patchwork Girl of Oz

Ojo the Unlucky seeks rare ingredients to restore his petrified uncle, aided by Scraps the Patchwork Girl, the Glass Cat, and other new friends. Their quest navigates laws of magic and the odd customs of Oz.

Little Wizard Stories of Oz

Six short adventures spotlight Dorothy, Ozma, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, Tik-Tok, and others in self-contained tales. Each vignette offers light incidents and character moments suited to younger readers.

Tik-Tok of Oz

Betsy Bobbin and her mule Hank are swept into Oz and join the Shaggy Man’s search for his captive brother, opposed by the Nome King. Tik-Tok and the comic army of Oogaboo figure in the campaign’s twists.

The Scarecrow of Oz

Trot and Cap’n Bill are drawn into Oz, where the Scarecrow helps them challenge the usurping King Krewl and aid Princess Gloria. Their efforts rely on cleverness, loyal allies, and a few eccentric creatures.

Rinkitink in Oz

Prince Inga, aided by the jovial King Rinkitink and the goat Bilbil, uses three magic pearls to rescue his parents from the Nome King. The journey blends peril, resourcefulness, and timely assistance from Oz.

The Lost Princess of Oz

Ozma vanishes along with key magical tools, prompting a wide-ranging search across Oz’s far corners. The trail leads to a secretive magician and a confrontation over stolen power.

The Tin Woodman of Oz

The Tin Woodman, with the Scarecrow and Woot the Wanderer, searches for his long-lost sweetheart, uncovering surprising complications from his past transformations. Their trek introduces new lands and curious beings tied to his origin.

The Magic of Oz

A boy discovers a potent transformation word and teams up with Ruggedo to sow mischief in Oz. Meanwhile, friends pursue a special birthday gift for Ozma, crossing paths with the disruptive magic.

Glinda of Oz

Ozma and Dorothy attempt to halt a looming war between the Flatheads and the Skeezers, only to become trapped in a submerged island city. Glinda undertakes high magic to resolve the impasse and save them.

THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ – Complete Collection: 16 Novels in One Premium Edition (Fantasy Classics Series)

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Introduction

Folklore, legends, myths and fairy tales have followed childhood through the ages, for every healthy youngster has a wholesome and instinctive love for stories fantastic, marvelous and manifestly unreal. The winged fairies of Grimm and Andersen have brought more happiness to childish hearts than all other human creations.

Yet the old time fairy tale, having served for generations, may now be classed as “historical” in the children’s library; for the time has come for a series of newer “wonder tales” in which the stereotyped genie, dwarf and fairy are eliminated, together with all the horrible and blood-curdling incidents devised by their authors to point a fearsome moral to each tale. Modern education includes morality; therefore the modern child seeks only entertainment in its wonder tales and gladly dispenses with all disagreeable incident.

Having this thought in mind, the story of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” was written solely to please children of today. It aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heartaches and nightmares are left out.

L. Frank Baum Chicago, April, 1900.

1. The Cyclone

Dorothy lived in the midst of the great Kansas prairies, with Uncle Henry, who was a farmer, and Aunt Em, who was the farmer’s wife. Their house was small, for the lumber to build it had to be carried by wagon many miles. There were four walls, a floor and a roof, which made one room; and this room contained a rusty looking cookstove, a cupboard for the dishes, a table, three or four chairs, and the beds. Uncle Henry and Aunt Em had a big bed in one corner, and Dorothy a little bed in another corner. There was no garret at all, and no cellar—except a small hole dug in the ground, called a cyclone cellar, where the family could go in case one of those great whirlwinds arose, mighty enough to crush any building in its path. It was reached by a trap door in the middle of the floor, from which a ladder led down into the small, dark hole.

When Dorothy stood in the doorway and looked around, she could see nothing but the great gray prairie on every side. Not a tree nor a house broke the broad sweep of flat country that reached to the edge of the sky in all directions. The sun had baked the plowed land into a gray mass, with little cracks running through it. Even the grass was not green, for the sun had burned the tops of the long blades until they were the same gray color to be seen everywhere. Once the house had been painted, but the sun blistered the paint and the rains washed it away, and now the house was as dull and gray as everything else.

When Aunt Em came there to live she was a young, pretty wife. The sun and wind had changed her, too. They had taken the sparkle from her eyes and left them a sober gray; they had taken the red from her cheeks and lips, and they were gray also. She was thin and gaunt, and never smiled now. When Dorothy, who was an orphan, first came to her, Aunt Em had been so startled by the child’s laughter that she would scream and press her hand upon her heart whenever Dorothy’s merry voice reached her ears; and she still looked at the little girl with wonder that she could find anything to laugh at.

Uncle Henry never laughed. He worked hard from morning till night and did not know what joy was. He was gray also, from his long beard to his rough boots, and he looked stern and solemn, and rarely spoke.

It was Toto that made Dorothy laugh, and saved her from growing as gray as her other surroundings. Toto was not gray; he was a little black dog, with long silky hair and small black eyes that twinkled merrily on either side of his funny, wee nose. Toto played all day long, and Dorothy played with him, and loved him dearly.

Today, however, they were not playing. Uncle Henry sat upon the doorstep and looked anxiously at the sky, which was even grayer than usual. Dorothy stood in the door with Toto in her arms, and looked at the sky too. Aunt Em was washing the dishes.

From the far north they heard a low wail of the wind, and Uncle Henry and Dorothy could see where the long grass bowed in waves before the coming storm. There now came a sharp whistling in the air from the south, and as they turned their eyes that way they saw ripples in the grass coming from that direction also.

Suddenly Uncle Henry stood up.

“There’s a cyclone coming, Em,” he called to his wife. “I’ll go look after the stock.” Then he ran toward the sheds where the cows and horses were kept.

Aunt Em dropped her work and came to the door. One glance told her of the danger close at hand.

“Quick, Dorothy!” she screamed. “Run for the cellar!”

Toto jumped out of Dorothy’s arms and hid under the bed, and the girl started to get him. Aunt Em, badly frightened, threw open the trap door in the floor and climbed down the ladder into the small, dark hole. Dorothy caught Toto at last and started to follow her aunt. When she was halfway across the room there came a great shriek from the wind, and the house shook so hard that she lost her footing and sat down suddenly upon the floor.

Then a strange thing happened.

The house whirled around two or three times and rose slowly through the air. Dorothy felt as if she were going up in a balloon.

The north and south winds met where the house stood, and made it the exact center of the cyclone. In the middle of a cyclone the air is generally still, but the great pressure of the wind on every side of the house raised it up higher and higher, until it was at the very top of the cyclone; and there it remained and was carried miles and miles away as easily as you could carry a feather.

It was very dark, and the wind howled horribly around her, but Dorothy found she was riding quite easily. After the first few whirls around, and one other time when the house tipped badly, she felt as if she were being rocked gently, like a baby in a cradle.

Toto did not like it. He ran about the room, now here, now there, barking loudly; but Dorothy sat quite still on the floor and waited to see what would happen.

Once Toto got too near the open trap door, and fell in; and at first the little girl thought she had lost him. But soon she saw one of his ears sticking up through the hole, for the strong pressure of the air was keeping him up so that he could not fall. She crept to the hole, caught Toto by the ear, and dragged him into the room again, afterward closing the trap door so that no more accidents could happen.

Hour after hour passed away, and slowly Dorothy got over her fright; but she felt quite lonely, and the wind shrieked so loudly all about her that she nearly became deaf. At first she had wondered if she would be dashed to pieces when the house fell again; but as the hours passed and nothing terrible happened, she stopped worrying and resolved to wait calmly and see what the future would bring. At last she crawled over the swaying floor to her bed, and lay down upon it; and Toto followed and lay down beside her.

In spite of the swaying of the house and the wailing of the wind, Dorothy soon closed her eyes and fell fast asleep.

2. The Council with the Munchkins

She was awakened by a shock, so sudden and severe that if Dorothy had not been lying on the soft bed she might have been hurt. As it was, the jar made her catch her breath and wonder what had happened; and Toto put his cold little nose into her face and whined dismally. Dorothy sat up and noticed that the house was not moving; nor was it dark, for the bright sunshine came in at the window, flooding the little room. She sprang from her bed and with Toto at her heels ran and opened the door.

The little girl gave a cry of amazement and looked about her, her eyes growing bigger and bigger at the wonderful sights she saw.

The cyclone had set the house down very gently—for a cyclone—in the midst of a country of marvelous beauty. There were lovely patches of greensward all about, with stately trees bearing rich and luscious fruits. Banks of gorgeous flowers were on every hand, and birds with rare and brilliant plumage sang and fluttered in the trees and bushes. A little way off was a small brook, rushing and sparkling along between green banks, and murmuring in a voice very grateful to a little girl who had lived so long on the dry, gray prairies.

While she stood looking eagerly at the strange and beautiful sights, she noticed coming toward her a group of the queerest people she had ever seen. They were not as big as the grown folk she had always been used to; but neither were they very small. In fact, they seemed about as tall as Dorothy, who was a well-grown child for her age, although they were, so far as looks go, many years older.

Three were men and one a woman, and all were oddly dressed. They wore round hats that rose to a small point a foot above their heads, with little bells around the brims that tinkled sweetly as they moved. The hats of the men were blue; the little woman’s hat was white, and she wore a white gown that hung in pleats from her shoulders. Over it were sprinkled little stars that glistened in the sun like diamonds. The men were dressed in blue, of the same shade as their hats, and wore well-polished boots with a deep roll of blue at the tops. The men, Dorothy thought, were about as old as Uncle Henry, for two of them had beards. But the little woman was doubtless much older. Her face was covered with wrinkles, her hair was nearly white, and she walked rather stiffly.

When these people drew near the house where Dorothy was standing in the doorway, they paused and whispered among themselves, as if afraid to come farther. But the little old woman walked up to Dorothy, made a low bow and said, in a sweet voice:

“You are welcome, most noble Sorceress, to the land of the Munchkins. We are so grateful to you for having killed the Wicked Witch of the East, and for setting our people free from bondage.”

Dorothy listened to this speech with wonder. What could the little woman possibly mean by calling her a sorceress, and saying she had killed the Wicked Witch of the East? Dorothy was an innocent, harmless little girl, who had been carried by a cyclone many miles from home; and she had never killed anything in all her life.

But the little woman evidently expected her to answer; so Dorothy said, with hesitation, “You are very kind, but there must be some mistake. I have not killed anything.”

“Your house did, anyway,” replied the little old woman, with a laugh, “and that is the same thing. See!” she continued, pointing to the corner of the house. “There are her two feet, still sticking out from under a block of wood.”

Dorothy looked, and gave a little cry of fright. There, indeed, just under the corner of the great beam the house rested on, two feet were sticking out, shod in silver shoes with pointed toes.

“Oh, dear! Oh, dear!” cried Dorothy, clasping her hands together in dismay. “The house must have fallen on her. Whatever shall we do?”

“There is nothing to be done,” said the little woman calmly.

“But who was she?” asked Dorothy.

“She was the Wicked Witch of the East, as I said,” answered the little woman. “She has held all the Munchkins in bondage for many years, making them slave for her night and day. Now they are all set free, and are grateful to you for the favor.”

“Who are the Munchkins?” inquired Dorothy.

“They are the people who live in this land of the East where the Wicked Witch ruled.”

“Are you a Munchkin?” asked Dorothy.

“No, but I am their friend, although I live in the land of the North. When they saw the Witch of the East was dead the Munchkins sent a swift messenger to me, and I came at once. I am the Witch of the North.”

“Oh, gracious!” cried Dorothy. “Are you a real witch?”

“Yes, indeed,” answered the little woman. “But I am a good witch, and the people love me. I am not as powerful as the Wicked Witch was who ruled here, or I should have set the people free myself.”

“But I thought all witches were wicked,” said the girl, who was half frightened at facing a real witch. “Oh, no, that is a great mistake. There were only four witches in all the Land of Oz, and two of them, those who live in the North and the South, are good witches. I know this is true, for I am one of them myself, and cannot be mistaken. Those who dwelt in the East and the West were, indeed, wicked witches; but now that you have killed one of them, there is but one Wicked Witch in all the Land of Oz—the one who lives in the West.”

“But,” said Dorothy, after a moment’s thought, “Aunt Em has told me that the witches were all dead—years and years ago.”

“Who is Aunt Em?” inquired the little old woman.

“She is my aunt who lives in Kansas, where I came from.”

The Witch of the North seemed to think for a time, with her head bowed and her eyes upon the ground. Then she looked up and said, “I do not know where Kansas is, for I have never heard that country mentioned before. But tell me, is it a civilized country?”

“Oh, yes,” replied Dorothy.

“Then that accounts for it. In the civilized countries I believe there are no witches left, nor wizards, nor sorceresses, nor magicians. But, you see, the Land of Oz has never been civilized, for we are cut off from all the rest of the world. Therefore we still have witches and wizards amongst us.”

“Who are the wizards?” asked Dorothy.

“Oz himself is the Great Wizard,” answered the Witch, sinking her voice to a whisper. “He is more powerful than all the rest of us together. He lives in the City of Emeralds.”

Dorothy was going to ask another question, but just then the Munchkins, who had been standing silently by, gave a loud shout and pointed to the corner of the house where the Wicked Witch had been lying.

“What is it?” asked the little old woman, and looked, and began to laugh. The feet of the dead Witch had disappeared entirely, and nothing was left but the silver shoes.

“She was so old,” explained the Witch of the North, “that she dried up quickly in the sun. That is the end of her. But the silver shoes are yours, and you shall have them to wear.” She reached down and picked up the shoes, and after shaking the dust out of them handed them to Dorothy.

“The Witch of the East was proud of those silver shoes,” said one of the Munchkins, “and there is some charm connected with them; but what it is we never knew.”

Dorothy carried the shoes into the house and placed them on the table. Then she came out again to the Munchkins and said:

“I am anxious to get back to my aunt and uncle, for I am sure they will worry about me. Can you help me find my way?”

The Munchkins and the Witch first looked at one another, and then at Dorothy, and then shook their heads.

“At the East, not far from here,” said one, “there is a great desert, and none could live to cross it.”

“It is the same at the South,” said another, “for I have been there and seen it. The South is the country of the Quadlings.”

“I am told,” said the third man, “that it is the same at the West. And that country, where the Winkies live, is ruled by the Wicked Witch of the West, who would make you her slave if you passed her way.”

“The North is my home,” said the old lady, “and at its edge is the same great desert that surrounds this Land of Oz. I’m afraid, my dear, you will have to live with us.”

Dorothy began to sob at this, for she felt lonely among all these strange people. Her tears seemed to grieve the kind-hearted Munchkins, for they immediately took out their handkerchiefs and began to weep also. As for the little old woman, she took off her cap and balanced the point on the end of her nose, while she counted “One, two, three” in a solemn voice. At once the cap changed to a slate, on which was written in big, white chalk marks:

“LET DOROTHY GO TO THE CITY OF EMERALDS”

The little old woman took the slate from her nose, and having read the words on it, asked, “Is your name Dorothy, my dear?”

“Yes,” answered the child, looking up and drying her tears.

“Then you must go to the City of Emeralds. Perhaps Oz will help you.”

“Where is this city?” asked Dorothy.

“It is exactly in the center of the country, and is ruled by Oz, the Great Wizard I told you of.”

“Is he a good man?” inquired the girl anxiously.

“He is a good Wizard. Whether he is a man or not I cannot tell, for I have never seen him.”

“How can I get there?” asked Dorothy.

“You must walk. It is a long journey, through a country that is sometimes pleasant and sometimes dark and terrible. However, I will use all the magic arts I know of to keep you from harm.”

“Won’t you go with me?” pleaded the girl, who had begun to look upon the little old woman as her only friend.

“No, I cannot do that,” she replied, “but I will give you my kiss, and no one will dare injure a person who has been kissed by the Witch of the North.”

She came close to Dorothy and kissed her gently on the forehead. Where her lips touched the girl they left a round, shining mark, as Dorothy found out soon after.

“The road to the City of Emeralds is paved with yellow brick,” said the Witch, “so you cannot miss it. When you get to Oz do not be afraid of him, but tell your story and ask him to help you. Goodbye, my dear.”

The three Munchkins bowed low to her and wished her a pleasant journey, after which they walked away through the trees. The Witch gave Dorothy a friendly little nod, whirled around on her left heel three times, and straightway disappeared, much to the surprise of little Toto, who barked after her loudly enough when she had gone, because he had been afraid even to growl while she stood by.

But Dorothy, knowing her to be a witch, had expected her to disappear in just that way, and was not surprised in the least.

3. How Dorothy Saved the Scarecrow

When Dorothy was left alone she began to feel hungry. So she went to the cupboard and cut herself some bread, which she spread with butter. She gave some to Toto, and taking a pail from the shelf she carried it down to the little brook and filled it with clear, sparkling water. Toto ran over to the trees and began to bark at the birds sitting there. Dorothy went to get him, and saw such delicious fruit hanging from the branches that she gathered some of it, finding it just what she wanted to help out her breakfast.

Then she went back to the house, and having helped herself and Toto to a good drink of the cool, clear water, she set about making ready for the journey to the City of Emeralds.

Dorothy had only one other dress, but that happened to be clean and was hanging on a peg beside her bed. It was gingham, with checks of white and blue; and although the blue was somewhat faded with many washings, it was still a pretty frock. The girl washed herself carefully, dressed herself in the clean gingham, and tied her pink sunbonnet on her head. She took a little basket and filled it with bread from the cupboard, laying a white cloth over the top. Then she looked down at her feet and noticed how old and worn her shoes were.

“They surely will never do for a long journey, Toto,” she said. And Toto looked up into her face with his little black eyes and wagged his tail to show he knew what she meant.

At that moment Dorothy saw lying on the table the silver shoes that had belonged to the Witch of the East.

“I wonder if they will fit me,” she said to Toto. “They would be just the thing to take a long walk in, for they could not wear out.”

She took off her old leather shoes and tried on the silver ones, which fitted her as well as if they had been made for her.

Finally she picked up her basket.

“Come along, Toto,” she said. “We will go to the Emerald City and ask the Great Oz how to get back to Kansas again.”

She closed the door, locked it, and put the key carefully in the pocket of her dress. And so, with Toto trotting along soberly behind her, she started on her journey.

There were several roads near by, but it did not take her long to find the one paved with yellow bricks. Within a short time she was walking briskly toward the Emerald City, her silver shoes tinkling merrily on the hard, yellow road-bed. The sun shone bright and the birds sang sweetly, and Dorothy did not feel nearly so bad as you might think a little girl would who had been suddenly whisked away from her own country and set down in the midst of a strange land.

She was surprised, as she walked along, to see how pretty the country was about her. There were neat fences at the sides of the road, painted a dainty blue color, and beyond them were fields of grain and vegetables in abundance. Evidently the Munchkins were good farmers and able to raise large crops. Once in a while she would pass a house, and the people came out to look at her and bow low as she went by; for everyone knew she had been the means of destroying the Wicked Witch and setting them free from bondage. The houses of the Munchkins were odd-looking dwellings, for each was round, with a big dome for a roof. All were painted blue, for in this country of the East blue was the favorite color.

Toward evening, when Dorothy was tired with her long walk and began to wonder where she should pass the night, she came to a house rather larger than the rest. On the green lawn before it many men and women were dancing. Five little fiddlers played as loudly as possible, and the people were laughing and singing, while a big table near by was loaded with delicious fruits and nuts, pies and cakes, and many other good things to eat.

The people greeted Dorothy kindly, and invited her to supper and to pass the night with them; for this was the home of one of the richest Munchkins in the land, and his friends were gathered with him to celebrate their freedom from the bondage of the Wicked Witch.

Dorothy ate a hearty supper and was waited upon by the rich Munchkin himself, whose name was Boq. Then she sat upon a settee and watched the people dance.

When Boq saw her silver shoes he said, “You must be a great sorceress.”

“Why?” asked the girl.

“Because you wear silver shoes and have killed the Wicked Witch. Besides, you have white in your frock, and only witches and sorceresses wear white.”

“My dress is blue and white checked,” said Dorothy, smoothing out the wrinkles in it.

“It is kind of you to wear that,” said Boq. “Blue is the color of the Munchkins, and white is the witch color. So we know you are a friendly witch.”

Dorothy did not know what to say to this, for all the people seemed to think her a witch, and she knew very well she was only an ordinary little girl who had come by the chance of a cyclone into a strange land.

When she had tired watching the dancing, Boq led her into the house, where he gave her a room with a pretty bed in it. The sheets were made of blue cloth, and Dorothy slept soundly in them till morning, with Toto curled up on the blue rug beside her.

She ate a hearty breakfast, and watched a wee Munchkin baby, who played with Toto and pulled his tail and crowed and laughed in a way that greatly amused Dorothy. Toto was a fine curiosity to all the people, for they had never seen a dog before.

“How far is it to the Emerald City?” the girl asked.

“I do not know,” answered Boq gravely, “for I have never been there. It is better for people to keep away from Oz, unless they have business with him. But it is a long way to the Emerald City, and it will take you many days. The country here is rich and pleasant, but you must pass through rough and dangerous places before you reach the end of your journey.”

This worried Dorothy a little, but she knew that only the Great Oz could help her get to Kansas again, so she bravely resolved not to turn back.

She bade her friends goodbye, and again started along the road of yellow brick. When she had gone several miles she thought she would stop to rest, and so climbed to the top of the fence beside the road and sat down. There was a great cornfield beyond the fence, and not far away she saw a Scarecrow, placed high on a pole to keep the birds from the ripe corn.

Dorothy leaned her chin upon her hand and gazed thoughtfully at the Scarecrow. Its head was a small sack stuffed with straw, with eyes, nose, and mouth painted on it to represent a face. An old, pointed blue hat, that had belonged to some Munchkin, was perched on his head, and the rest of the figure was a blue suit of clothes, worn and faded, which had also been stuffed with straw. On the feet were some old boots with blue tops, such as every man wore in this country, and the figure was raised above the stalks of corn by means of the pole stuck up its back.

While Dorothy was looking earnestly into the queer, painted face of the Scarecrow, she was surprised to see one of the eyes slowly wink at her. She thought she must have been mistaken at first, for none of the scarecrows in Kansas ever wink; but presently the figure nodded its head to her in a friendly way. Then she climbed down from the fence and walked up to it, while Toto ran around the pole and barked.

“Good day,” said the Scarecrow, in a rather husky voice.

“Did you speak?” asked the girl, in wonder.

“Certainly,” answered the Scarecrow. “How do you do?”

“I’m pretty well, thank you,” replied Dorothy politely. “How do you do?”

“I’m not feeling well,” said the Scarecrow, with a smile, “for it is very tedious being perched up here night and day to scare away crows.”

“Can’t you get down?” asked Dorothy.

“No, for this pole is stuck up my back. If you will please take away the pole I shall be greatly obliged to you.”

Dorothy reached up both arms and lifted the figure off the pole, for, being stuffed with straw, it was quite light.

“Thank you very much,” said the Scarecrow, when he had been set down on the ground. “I feel like a new man.”

Dorothy was puzzled at this, for it sounded queer to hear a stuffed man speak, and to see him bow and walk along beside her.

“Who are you?” asked the Scarecrow when he had stretched himself and yawned. “And where are you going?”

“My name is Dorothy,” said the girl, “and I am going to the Emerald City, to ask the Great Oz to send me back to Kansas.”

“Where is the Emerald City?” he inquired. “And who is Oz?”

“Why, don’t you know?” she returned, in surprise.

“No, indeed. I don’t know anything. You see, I am stuffed, so I have no brains at all,” he answered sadly.

“Oh,” said Dorothy, “I’m awfully sorry for you.”

“Do you think,” he asked, “if I go to the Emerald City with you, that Oz would give me some brains?”

“I cannot tell,” she returned, “but you may come with me, if you like. If Oz will not give you any brains you will be no worse off than you are now.”

“That is true,” said the Scarecrow. “You see,” he continued confidentially, “I don’t mind my legs and arms and body being stuffed, because I cannot get hurt. If anyone treads on my toes or sticks a pin into me, it doesn’t matter, for I can’t feel it. But I do not want people to call me a fool, and if my head stays stuffed with straw instead of with brains, as yours is, how am I ever to know anything?”

“I understand how you feel,” said the little girl, who was truly sorry for him. “If you will come with me I’ll ask Oz to do all he can for you.”

“Thank you,” he answered gratefully.

They walked back to the road. Dorothy helped him over the fence, and they started along the path of yellow brick for the Emerald City.

Toto did not like this addition to the party at first. He smelled around the stuffed man as if he suspected there might be a nest of rats in the straw, and he often growled in an unfriendly way at the Scarecrow.

“Don’t mind Toto,” said Dorothy to her new friend. “He never bites.”

“Oh, I’m not afraid,” replied the Scarecrow. “He can’t hurt the straw. Do let me carry that basket for you. I shall not mind it, for I can’t get tired. I’ll tell you a secret,” he continued, as he walked along. “There is only one thing in the world I am afraid of.”

“What is that?” asked Dorothy; “the Munchkin farmer who made you?”

“No,” answered the Scarecrow; “it’s a lighted match.”