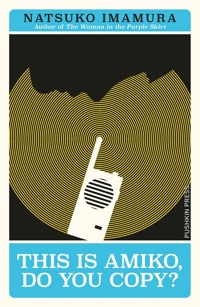

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A moving novella about a misunderstood young girl, from the author of The Woman in the Purple Skirt - part of Pushkin's second Japanese Novella seriesMeet young Amiko. She's one of a kind-full of life and good intentions, but with no filter or boundaries. She happily inhabits a world of her own making, oblivious to offences given or taken. But when it comes to expressions of love, where conflicting signals are hard to grasp and a heart is easily broken, there can be unintended consequences.An aching, tender depiction of belonging and loss, This is Amiko, Do You Copy? is a portrait of childhood through the eyes of an irrepressible young girl.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 107

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THIS IS AMIKO, DO YOU COPY?

NATSUKO IMAMURA

Translated from the Japanese by

HITOMI YOSHIO

PUSHKIN PRESS

THIS IS AMIKO, DO YOU COPY?

WITH A SMALL HAND SHOVEL AND A CRUMPLED PLASTIC BAG in her hands, Amiko stepped out the back door of the house. For the past couple of nights it had rained, making the path so muddy that her sandals had to be peeled off the ground as she walked, but this morning, thanks to yesterday’s sun, they met no such resistance. The mud on the edges of her sandals had hardened gray. She’d run them under the faucet after she’s done picking the violets, she decided. Amiko passed the overhanging eaves along the side of the house and walked up the short, gentle slope to the field, where she saw white azaleas blooming by the side of the road. She stopped and wondered if she should pick azaleas instead, but without sturdy shears to cut the branches she decided to settle on the violets after all.

Normally the slope was overgrown with weeds, but last week a kind monk from the temple nearby came over with a mower and made it nice and trim. It didn’t feel prickly to walk on anymore, and in appreciation Grandmother gave the monk some sweet green dango dumplings she’d rolled by hand.

Amiko walked up the short slope to the small field where Grandmother tended the cucumbers, eggplants, daikon, and herbs that were planted each year. Snow peas were in season from spring to early summer, and recently they’d been appearing at breakfast, lunch, and dinner, in every dish from stews and soups to stir-fries. Amiko was getting tired of them. She walked past the flat green pods hanging on their vines, averting her eyes, and continued toward the thicket where a persimmon tree bore small fruit every other year.

There, in the reddish-yellow earth, violets bloomed. It was always shaded and damp under the leafy persimmon tree, but perhaps because the soil was rich with nutrients, wild violets thrived, their flowers a vivid dark purple. Amiko wedged her shovel into the earth and dug up the flowers by their roots. When she tried to slip them into the plastic bag, she couldn’t find the opening. Her right hand was holding the shovel and her clumsy left hand was of no use, so she used her back teeth and her tongue to open the bag. With shaky hands that made the petals tremble, she slid the shovel into the bag and slowly pulled it out, the handle straight up. She patted the roots and the soil from the outside of the bag so that the stems would be upright. Then, with a “one, two, three”, Amiko got back up.

On her way down the hill, Amiko saw little Sakichan coming toward her on stilts. She was so far away, the size of a pea, but it had to be her. Perfect timing! Amiko waved her hand, which was still holding the shovel, and shouted, “Hey!” There was no response. Perhaps her voice didn’t carry, or perhaps she was too far away for Saki-chan to see her. Even if she’d heard her, she couldn’t wave back because her hands were clutching the stilts. Saki-chan was making steady progress forward, but moved so slowly that it seemed like she was just stamping her feet in the same spot.

Saki-chan lived nearby and went to the local elementary school. Whenever she came over to Amiko’s house, she would appear on stilts. Amiko, who didn’t know how to use stilts, was amazed and impressed by her persistence—the house was at least fifteen minutes away walking normally. The little visitor was always delighted when she arrived and was treated to sweets and juice, or was given flowers to take home. A few days ago, on the footpath between the rice paddies, Saki-chan had found some pretty yellow flowers that Amiko knew were toxic. Amiko tried her best to say no, she couldn’t have them, but Saki-chan begged. This was unusual, so Amiko gave in and snipped four or five flowers and wrapped them in newspaper for her. The next day, Saki-chan came back—on stilts, as if it were a ritual—with a glum look on her face. “My mom got mad and made me throw the flowers away. She said they were dirty,” Saki-chan pouted. “And she blamed you for it, Amiko. I’m so sorry…” She pressed her palms together and bowed sheepishly. Amiko told her not to worry. After all, it was Amiko who had given her those toxic flowers. But the little girl was truly sorry, bowing over and over, her eyebrows arched downward, feeling she’d done Amiko wrong and ready to burst into tears. Amiko decided that the next time she saw Saki-chan, she’d give her flowers that would make her mother happy. That was why she had come outside to pick the violets.

Amiko felt that she should be good to her friends. If Saki-chan came to see her on the days she didn’t have school, it probably meant she was fond of Amiko. Amiko was fond of her too. Whenever Saki-chan asked her to do something, like make a big yeee grin with her teeth clenched, she would do it. Saki-chan was fascinated by the dark hole that appeared in Amiko’s mouth, which was missing three front teeth. To be exact, it was the left middle tooth, the one to the left of that, and the one to the left of that. When Saki-chan first noticed it, she cried out, “What the heck?!” and laughed so hard she could barely cover her mouth with her hands. Then she asked Amiko how it happened. Amiko told her that in junior high school a boy punched her in the mouth and her teeth went flying, which surprised Saki-chan so much she bent over backward. Amiko went on to say that the boy was named Nori and that she’d been in love with him since she was little. Saki-chan, who had a crush on a soccer boy, wanted to know what it was like to be punched in the mouth by a boy you were in love with.

Amiko didn’t know how to explain. She wanted to, but it had all happened when she lived in a house far away, before she came to live with Grandmother. She didn’t remember much from those days.

“That’s boring,” Saki-chan complained. But she was captivated by the gaping hole in Amiko’s mouth and moved in close for a better look. That was easy enough. Amiko could show her the dark hole as much as she wanted. Yeeee. She made a big grin.

CONTENTS

ONE

AMIKO GREW UP AS THE SECOND CHILD IN THE TANAKA FAMILY until the day she moved out at the age of fifteen. She had a father, a mother, and an older brother who became a juvenile delinquent.

Back when Amiko was in elementary school, Mother taught a calligraphy class at home. The classroom was small and simple, with three long rectangular tables arranged in an eight-mat tatami room where Mother’s mother used to sleep. Now the floor was covered with a red rug from corner to corner. Next to this room was the so-called Buddha room, where the butsudan was placed, and across the hall was the kitchen–dining room. The classroom was connected to a veranda, and that’s where the calligraphy students entered after removing their shoes. Mother had wanted it this way. Otherwise, if the students entered through the front door, they’d have to walk past the Buddha room and the kitchen–dining room and they’d see into the family’s living spaces.

In front of the veranda was a small yard, where Father parked his car. Whenever the car was there, the students had to step sideways in the gap between the car and the concrete wall of the house to get to the veranda, which resulted in Father’s navy-blue car getting scratched by the metal snaps on their school backpacks. When that happened, Father never complained but would apply a cream onto a sponge and rub it over the scratches, which made them vanish without a trace. “It’s a magic sponge,” he would say. Amiko begged Father to let her use the magic sponge, and from then on she would inspect the car daily for scratches before anyone else could discover them and rub them out with great enthusiasm. As a result, Father’s car always glistened. But some scratches were deep, and no magic could remove the words amiko the fool. Amiko tried valiantly to rub it out—“I almost got it,” she said, checking from different angles—but the etched words were never completely gone.

Amiko was in the first grade and could read her own name, but not the kanji for fool. When she asked Father what it said, he pushed up his glasses and replied, “Hmmm… I dunno.”

The next day, the navy-blue car was covered with a thick rain cover, which remained in place rain or shine.

Amiko missed the thrill of rubbing out scratches, but there were plenty of other fun things to do—like peeking into “the red room” (she called it that because of the red rug) when Mother was teaching a class. Amiko had been strictly forbidden to enter the classroom, so she had to be sneaky. How exciting this was. Yelling “Pee! Pee! Pee!”, Amiko would pretend to go to the toilet, tiptoe into the adjacent Buddha room holding her breath, and pry open the sliding doors to create a tiny gap. Sneaking looks into the red room with her left eye, she would see the back of Mother’s head, her long black hair pulled tight into a ponytail. Beyond, she would see students facing her way. Around the same age as she was, they were lined up in front of the tables, sitting upright on the floor with their legs tucked under properly. Her brother Kota, who was two years older, was one of the students. He had good posture and was holding a brush. Amiko didn’t know any of the other students, but she couldn’t resist the temptation of their whisperings and the alluring scent of ink mixed with the smell of newspaper they used for practice. The smell somehow made her want to pee for real, and she would have to go back and forth to the toilet after all.

One summer day, Amiko hid behind the sliding door as usual, occasionally slipping away to go to the toilet.

At one point, Amiko went into the kitchen and returned with a piece of corn cob that Mother had prepared for her. She got into position and began gnawing off one kernel of the sweetcorn at a time, when she noticed that a boy was looking directly at her. He was sitting perfectly still with a brush in his hand, staring at Amiko with big round eyes. The glass door to the veranda was slightly open, creaking gently as the breeze blew in and ruffled the boy’s bangs, which glowed in the evening sun. The only other sound to be heard was the crunching of the yellow kernels of corn, which echoed deeply in Amiko’s ears.

The boy put down his brush. He picked up the sheet of paper from his desk, turned it around, and raised it up to his face. Written on the white sheet was こめ, the kana for komé, meaning rice. The calligraphy was neatly spaced and beautiful, so much more than Amiko’s writing. Then, perhaps because the boy had dabbed his brush too deeply in the ink, a drop began to form on the bottom edge of こ. It looked like drool trickling down from a smiling mouth. As Amiko watched, spellbound, the cob of corn in her hand grew hotter and hotter. Her overgrown fingernails dug into the kernels and penetrated the cob. Sweet juice oozed out, mixing with the sweat of her hands and becoming sticky. Her mind became foggy, filled only with the vision of the boy before her.

Then, suddenly, someone shouted, “It’s Amiko!”

The students all looked up at once.

“Amiko is watching us!”

One of the boys stood up, full of energy. He straightened his arm and pointed the tip of his brush toward her. “Tanaka-sensei, she’s right behind you!”

Mother’s head of black hair whipped around, and in the next moment her eyes, narrowed and pointed, landed on Amiko.

As Mother approached, Amiko glanced up at the mole under her chin. “But I didn’t go inside,” Amiko protested. “I was just looking!”