Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

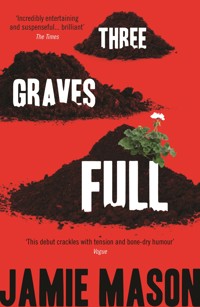

Hitchcock meets the Coen Brothers in a darkly comic suspense novel with the tense pacing of a thriller and the beauty of the best of literary fiction . "A ripping good novel" The New York Times "An astonishing debut novel, smart and stylish... with an absolutely Hitchcockian menace" Peter Straub There is very little peace for a man with a body buried in his backyard, but it could always be worse. Lonely widower Jason Getty killed a man he wished he'd never met, and buried him behind his own house. A year later, just as he's ready to move on, Jason's gardeners dig up two other bodies on his property, a man and a woman. Apparently unrelated, the surprising stories behind each murder begin to unravel as Jason becomes entangled in a race against time, two determined police detectives, and his own conscience. Jamie Mason's dark imagination, tender wisdom and sharp sense of comedy take us inside the hearts and souls of all her characters - policemen, criminals, victims, innocent bystanders and one truly remarkable dog. Psychologically brilliant, relentlessly entertaining and irresistibly pitch-perfect, Three Graves Full is a dazzling literary debut. "Mason strides confidently into Coen brothers territory with her highly entertaining, solidly plotted debut about loneliness and the need for companionship" Publishers Weekly (starred review) "Three Graves Full is something special - an offbeat, high-class, pacy mystery that blends black humour with dark lyricism, and deft, intricate plotting with dead-on psychological insight. A gem of a debut" Tana French "Portraying characters so well and so thoroughly, examining and explaining their motives even for murder, requires a level of skill that is rare, marking this an astonishingly accomplished debut and Mason as a writer to watch very closely" Booklist, starred review, A Top Ten Crime Novel of 2013 "Mason's quirky debut novel deftly weaves dark humor into a plot that's as complicated as a jigsaw puzzle but more fun to put together... Mason's written a dandy of a first outing with not a single boring moment" Kirkus "Filled with biting wit and great prose style, Three Graves Full by newcomer Jamie Mason may be the debut of the year" Bookspan

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 451

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

for Art, Julia, and Rianne—always and for the finest practitioner of long-distance brain surgery in all the world, Graeme Cameron

All places are alike, and every earth is fit for burial.

—Christopher Marlowe

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Copyright

1

There is very little peace for a man with a body buried in his backyard. Jason Getty had grown accustomed to the strangling night terrors, the randomly prickling palms, the bright, aching surges of adrenaline at the sight of Mrs. Truesdell’s dog trotting across the lawn with some unidentifiable thing clamped in its jaws. It had been seventeen months since he’d sweated over the narrow trench he’d carved at the back border of his property; since he’d rolled the body out of the real world and into his dreams.

Strangely though, it wasn’t recalling the muffled crunch of bone that plagued him, nor the memory of the cleaning afterward, hours of it, all the while marveling that his heart could pound that hard for that long. No. It was that first shovelful of dark dirt spraying across the white sheet at the bottom of the grave that came to him every time he closed his eyes to sleep. Was it deep enough? He didn’t know—he wasn’t a gravedigger. Then again, in his mind he wasn’t a murderer either, but facts are facts.

No disaster can stay shiny and new forever. No worry has ever been invented that the mind cannot bully down into mere background noise. For the first few days and weeks, Jason thought of nothing else. Every night, sometimes twice a night (and one fretful night, the first time it rained, it was six times), he slipped through the shadows to the margin of evergreen and poplar that marked the end of his acreage to check and recheck the integrity of his secret. To his eyes, the irregular rectangle of disturbed earth might as well have been bordered in neon. It was a gaudy exhibit to the barbaric instinct that lay curled at the core of every tamed human brain. Evolution had brought us out of the trees, then culture had neutered the beast, but even a eunuch can get angry.

To his right, his little rancher offered up a cozy nook that glowed and whirred with modern conveniences. To his left and just beyond the trees, the ground fell away to a cleared swath of municipal land dotted with linked pairs of electrical towers marching off into the civilized distance. But this middle ground called back to him over and over, whispering, chanting in time with his knocking heart, to keep him ever mindful of the one moment he’d lost millennia of breeding and found himself the puppet of a howling primal rage.

Jason didn’t sleep. He didn’t eat. He filed his reports and managed his client list robotically and correctly, without forgetting for more than a few seconds at a time that a body was moldering under several feet of topsoil and pine needles thirty yards from his back door.

Then one day, Dave from Accounting made a joke and Jason laughed. The sound of it rang sudden and carefree, natural as a lightning strike. His skin stung as a warning blazed though his blood. You’ve killed someone, you idiot. You buried him out back. Don’t forget! But by that time, five minutes had already gone by, and he found, as more days came and went, that the spell became a worry, became a niggle, became part of who he was.

The heater blew his own sour breath back in his face as he sped home from the first time he’d allowed himself a break. He’d blurted, “Yeah, sure,” at the unexpected invitation to Friday’s after-work beers. The glow of good cheer faded with the parting handshakes, and in its place needles of chills played at odds with the sweat running in all his creases. No amount of anxious accelerator stomping made the drive home take less than forever. He’d bypassed the house altogether and fled straight into the woods, knowing he’d find … what? Nothing. Just trees and wooded rustling-quiet and the distant, sibilant whisper of freeway traffic.

The ground kept its promise to lie still, and the pines and leafy trees were faithful to sift camouflage over the scene. Jason’s thoughts by day took on an uncriminal rhythm, but the burial came back each night to play against the inside of his eyelids, only in more Technicolor than there had actually been on that moonlit October night.

The anniversary of the incident erased much of his progress. Jason imagined the universe contained just enough irony to disallow him the turning of that last calendar page; the one that would symbolically stretch the hundred-odd steps from the back deck to the body, as if day 366 were a magical meridian in time—his own personal New Year’s Day. He marked it, survived it, and spent another winter hibernating in a cocoon of fading anxiety. The nightmares, however, they lingered.

That spring, the neglected upkeep of his house snagged his attention and gave rise to a new and improved brand of concern. The shrubs were overgrown and the small front garden bristled with three seasons of vagabond weeds, but somehow the thought of wielding a shovel and hoe turned his spine to putty and made everything in the pantry vaguely nauseating. Three consecutive Saturdays had him bravely facing down the shed door and left him three consecutive Sundays in bed with a fever of uncertain origin.

If home is where the heart is, Jason had lived in his throat for a long time. As such, not a lot of maintenance had been required beyond crunching antacids to cool the pipes. His paranoia resurfaced with the surety that the neighbors, even as spread out as they were, would begin to wonder about the shaggy disarray of his lawn. The nagging cycle of peering over his shoulder and in between the curtains crested again.

In May, the riotous blooming of dandelions and sow thistle left him with little choice: do it yourself or hire out. Dearborn’s Landscaping contracted for the lowest bid to aerate and seed the front lawn, prune the bushes, weed and edge the front and side mulch beds, and plant low-maintenance perennials all around the entry and up the driveway. Jason aimed to keep himself from yard work for as long as possible and didn’t mind writing off the cost one little bit. A craggy foreman named Calvin brought two young men and an open-mesh trailer full of rusty gadgets for the two-day job of grooming away a year and a half of avoidance.

Jason hovered out front all that first morning: washing his car, chatting up Calvin, making a Broadway production of checking the mail—twice at that, and well before the postman had even made his rounds. By midday, he dared to breathe a little easier, completely convinced that none of them would go one step farther than they had to. A bold line had been drawn at the edge of their contractual obligation, and obviously no one was headed out back for fear of finding anything more to do.

He made himself a sandwich and watched the workmen from the windows for a while before wandering off to the den. He enjoyed a dog show on television, one ear straining for any out-of-place thump or rustle from the men outside. Hearing no such thing and wrung out from all his chafing, Jason let his head fall back against the easy chair. Just for a moment. The late-afternoon sun slanting in through the window weighed like warm gold coins on his eyelids. He fought the drag of them, but the orange glow was so pretty, so cheerful. The recliner cradled him close while the ceiling fan shushed the thoughts from his head.

In his dream, a young man in Dearborn’s coveralls knelt in the grass. He smiled and nodded up to Jason after having just slotted the trowels and handforks back into his toolbox, absently brushing his hands clean of their work. Jason yammered gibberish. He flailed and capered, willing to do a bare-naked anything to stall off the inevitable moment when the gardener would look down again to gather up his kit. The young man, his face familiar but somehow not quite recognizable, listened intently as Jason babbled, all the while wiping bloody dirt from his hands onto a corner of white sheet that poked up from a ragged rent in the ground.

Jason tipped the carafe fully upside down to fill the mug beyond common sense’s recommended limit. Once he’d added the cream, he realized that no one outside a Zen-tranced surgeon was lifting it from the counter without spilling, and no doubt burning, a sloppy mess all over hand and Formica alike.

“Crap,” he muttered, and leaned down to blow steam from the brimming cup. The doorbell startled his pursed upper lip into the scalding coffee, and one flinch later, the imagined mess materialized pretty much as he’d predicted, although it was his lip, not his hand, that stung. “Crap,” he said again. At least the spill had left the mug manageably full. He gave it half a turn against the dish towel and brought it with him to the door.

Calvin and crew had arrived shortly after eight, expecting to be done by lunchtime. The front yard was now trim and tidy, and the flower bed’s machined edges were well beyond what Jason could have managed on his own with the shovel, even if he had been able to bring himself to touch it.

He’d felt better just watching them unload the trays of flowers. The glow of the colors was contagious, and the sprays of healthy green radiated rightness. Respectability had to be a well-kept garden, and Jason’s mood went warm at the sight of it. The workers had been at it for nearly two hours, and Jason expected a blushing request for restroom privileges. What he got instead, at the front door, was an eyeful of an ashen-faced Calvin.

“Mr. Getty—” It was all Calvin could manage.

“Yes?” Jason’s mouth answered on autopilot while a roar rose up in his ears, a nearly mechanical hum, as his mind calculated what in his yard could make a suntanned gardener turn white and trembling.

“Mr. Getty, we’ve found something. We think you’d better come have a look.”

“All right, just let me get some shoes.” Jason stumbled as he turned, sloshing more coffee out of the cup onto his pants and the floor. But what did it matter? The game was up. Thank God, I can’t do this. No, you can play dumb. You can run. Why did they go back there? Why were you stupid enough to hire a landscaping crew, you worthless, spineless … must think: What the hell am I going to say?

Somewhere on the way from the closet to the front door, Jason’s mind went blank. He stopped berating himself and gave up casting around for canned answers to the inevitable questions awaiting him in the backyard. He simply walked out the door, pulling it shut behind him. Calvin stood, twisting his red baseball cap in his calloused hands. Jason nodded to him and followed him off the front stoop, numbed straight through to the soles of his feet.

The four of them gathered in a cluster, standing closer than men who didn’t know each other normally would, staring down into the rich black-brown of newly turned soil. Jason had a number of abandoned ambitions and had once dreamed of being a doctor. He had pored over medical encyclopedias, memorizing words that carried mystery and clout on their convoluted syllables: frontal, parietal, sphenoid, zygomatic—they flooded his mind as he looked at the ground and labeled what he saw, what the other men saw as forehead, crown, temple, and cheek. The skull’s eye sockets were filled with peat, but there was no mistaking the contours and ridges. A human being, or part of one at least, had been unearthed on Jason Getty’s property.

Four men stood, three in horror and revulsion and one in complete bewilderment. Jason had followed Calvin down the front steps like a man on his way to the gallows. Part of his mind noted, with a pang of regret as they passed, that the living-room windows needed washing. He had turned around the corner of the west wall, past the den window with its closed blinds, his eyes glued to the label jutting up from the collar of Calvin’s blue work shirt—itching to reach out, to tuck it in, and make things right. His musings led him to run up Calvin’s heels, not having noticed that he’d stopped. Not having expected him to stop nearly so soon. They hadn’t even cleared the back of the house.

The foreman and his crew had uncovered a body, but not the body that Jason had interred all those months ago at the back edge of the yard. That body remained tucked into the shade of the trees and was as far away as it could be and still have Jason Getty paying the taxes on its gritty resting place. This skull turned a baleful eye from the mulch bed at the side of the house, directly underneath Jason’s bedroom window, and he had no idea who it was.

2

Leah Tamblin hit the garage-door button again. The hinged panels trundled up and shuddered to a halt only a third of the way open. A taunting slice of spring morning reflected in off the driveway. The defeated motor took a moment of silence, reversed itself, and the door rattled back down again, making Leah officially late for work.

“Oh, come on.”

The dangling release handle proved a test of her farthest reach, but eventually she flung the door up its tracks and backed the car out of the garage and into her next dilemma. Leah, being five feet and half an inch tall on a poufy-hair day, was too short to bring the door back down without a ladder, and no way she was leaving her garage door opened to the elements, climatic or criminal.

Leah closed her eyes and took a deep, calming breath, which might have worked wonders had she thought to unclench her grinding teeth. If she was going to be late, she could at least have the repair appointment in the works. She stomped back into the house and dialed her office number, pulling the telephone directory from the bottom cupboard. The phone tucked into place between her cheek and shoulder just as her supervisor answered the call.

“Chris, hi. It’s Leah.” She flipped and rifled the pages of ads in the vicinity of G for garage-door repair. “I’ve got technical difficulties this morning. I’m gonna be a little l—” The flyer slipped out from between the phone book’s pages, from somewhere near the end of the alphabet, as she lifted the book for repositioning. The corner of the paper was brittle and wrinkled from having been wet at some point. It slid across the countertop, and she stopped it with a tentative palm to keep it from sailing onto the floor. Reid smiled up at her, frozen in midparty mirth, from under the bold proclamation MISSING. Chris, on the other end of the line, cleared his throat, but out of necessity or impatience she couldn’t tell. Truthfully, she barely noticed. “—late,” she finished in a whisper.

Reid’s face was still around. In the living room, his eyes crinkled over smiles of varying ease in posed school portraits that chronicled the variations in the rock-star hairstyles of his younger years. There were band photos and a few scattered candid shots in easel-backed frames throughout the house. Stuck to the refrigerator, there was even a magnet made from a snapshot of the two of them at the beach, sunny and windblown, grinning at the camera with their arms wound around each other. But these were fixtures, all but invisible to her. In their routineness, they were easier to forget than the jarring holes they left in her peripheral vision when she tried to pack them away.

His clothes had hung in the closet until the dust on the shoulders of his darker shirts was a grim billboard to his absence. But to be rid of the dust, she’d have to wash the clothes, and the thought of doing a load of laundry for a man who would never need it was more macabre than simply leaving everything just as it was. Eventually, she’d packed his things into boxes and, once she’d grown weary of tripping over them, moved the boxes to the attic.

The paraphernalia of the search had been the hardest to gather up for storage. She’d left stacks of papers and bundles of relevant mail spread out over the counter for so long, as if they still had potential; as if the clues and leads were only stubbornly disconnected, waiting to be joined together by a worthy Dr. Frankenstein and jolted awake to finish Reid’s rescue. Lowering the lid over the box of police reports, press clippings, and her own notebooks of lists and contacts had sent her running to the bathroom, falling to her knees, and dry heaving over the commode until flashes of light swam across her eyes. Holding this morning’s stray reminder of that time in her life, she couldn’t remember having stashed one of the flyers in the phone book or why she would ever have done such a thing in the first place.

Reid had gone out with an itinerary: stop by his work for a bar-staff training meeting; hit the music store for guitar strings; Home Depot for an extension cord and lightbulbs; and bring back a late lunch. He had made his meeting and the trip to the music store. Four days later, the police identified the burned-out shell of his car on a gravel road nearly sixty miles away.

The day he disappeared dragged on forever: annoyance first at the inconvenience, suspicion next, culminating in a shouting match with Dean, his brother, when Leah accused him of knowing “exactly where he is and covering for him just like you did the last time.” Dean’s insistence that they phone the police, once the sun had set and Reid’s voice mail registered full, had sent the mistrust cresting over into fear. Dean was never without a joint or two in his pocket, and he was well-known by the authorities for his petty association with the fraternity of usual suspects. He avoided the local police as much as they kept their eyes peeled for him, and nothing short of disaster would have him inviting the cops into his life.

There was no real sleep with Reid missing. Not for the initial few days. Somewhere in the first forty-eight hours, the lights went out at someone else’s say-so and Leah’s eyelids closed in spite of themselves. She’d lie down, achingly alone, at everyone’s insistence, and without her consent her brain would unhook itself from consciousness. But if there was a footfall on the stairs, or a ringing telephone, or headlights sweeping across the bedroom walls, the crashing, pounding awareness of all that was wrong with the world burned away the blankness in an instant.

Leah’s waking hours cycled through minutes of fretting; of franticdoing, and the marshaling of the troops—friends, relatives, and volunteers—to do also; of praying and discovering that she alternately believed in God and loved Him, believed in God and hated Him, and that she was kidding herself and there was no God. Then there were the seconds she forgot that anything was wrong at all.

When she’d gone looking for a recent photo for the flyer, she’d found Reid’s AWOL sunglasses in the desk drawer and picked them up with a laugh, turning around to tease him for his forgetfulness. Through the dining room she saw Sheila, Reid’s mother, nodding soberly to a police detective at the kitchen counter. For three seconds and one clear, deep breath, Leah had been free of the day. Reality seeped back through her in a slow, sad flood. A rising, cold dread was what spoiled these moments, not the hot collision of panic and urgency that hurled her from sleep. Her brain continued to trick her like this, running for refuge measured in a few calm heartbeats. It happened more and more as the exhaustion set in.

The first three days were a series of battles with the experts over whether there was any real problem at all. By the end of the evening on the first day, Reid’s family and closest friends were convinced there had been some sort of an accident. Dean went driving the most likely routes Reid would have taken, and Sheila dialed the closest hospitals with shaking fingers. Leah spoke to the manager of Neptune, the club where Reid tended bar and played most of his gigs. She called the other band members, who dropped everything and came running, as she knew they would. The gravity of phoning the police, with its implied admission of catastrophe, smothered a quiet down over the group as they waited for the patrol cruiser.

The police confirmed that he’d not been arrested and they took a preliminary report, all the while trying to disguise boredom as reassurance. Reid was a young man with a car and a wallet full of credit, and the obvious implication was left to hang in the air. They grilled Leah as to whether they’d argued, which she denied. The next morning dawned, impossibly surreal, as the first day since the eighth grade that Leah didn’t know where Reid was.

Of course, plenty of hours had been unaccounted for in the previous sixteen years, lost hours that had always been a point of contention. Reid loved Leah, there was no doubt. And she loved him. They had been a couple since Mrs. Doyle’s homeroom class. But his head had, on occasion, been turned. When she had known or suspected, Leah would fume and rant for a few hours, then withdraw into the threat of unending silence. Eventually she would give in to the barrage of honest remorse. Reid was always hugely sorry in proportion to how much he loved her.

Leah was neither weak nor stupid; she was practical. In her mind, relationship was compromise, and compromise was a simple contract. Everyone offers up something as a loss in order to gain a list of must-haves. Constant fidelity was the sacrifice in this transaction, but Reid was affectionate, talented, and celebrated as the life of the party. In all of his faults, what was good was real. He had held her hand on the science-class field trip through the old-growth forest and never let her go. As angry as she ever got with him, she always felt him there in her left hand, a warmth that tingled in her palm and held her back from the uncharted wildness that could (and surely would if given half the chance) gobble her up and erase her as if she’d never existed at all.

Reid on his own, though, was only part of the arrangement he secured for Leah. It was family, and the years of warm belonging she’d felt, that kept her at his side. Ideas and ideals were fine enough, but Reid, with his smile and off-brand devotion, delivered a clan, solidly there, that loved Leah more than her blood ties ever had: an amusing puppy of a brother in Dean and a mother, with all the sweet connotations the word can hold, in Sheila. Sheila, in her terribly fragile health, owned Leah’s loyalty and heart more than her son ever had.

And it was Sheila, with her gentle manipulations, who had brought them all to the very threshold of a wedding to keep them together. The police officers had made much of how Reid had vanished thirteen days before he was due to walk down the aisle. Cold feet made such easy work of a missing person’s investigation. And indeed, a set of cold feet figured prominently in the goings-on, but they weren’t missing. They carried Leah from room to room, trying to stride off the nervous energy of guilt.

She’d walked with Reid into one very real and tangly wood when they were children, and little by little over the years they’d walked right out into another one, a metaphorical snarl of need and obligation. She knew very well the long, swooping drop between playing along with a situation and being legally bound to it. She’d come to the very edge of that bridge and peered between the slats, hesitating at the choice to cross or jump.

With Reid gone, Leah’s manic pacing wore flattened tracks into the carpet, the edgy, useless circles run to purge regret from a bride who had been praying for a way out. But the house, she found, was a treadmill, and she couldn’t outrun the secret, little thrills of what her life might yet be. She didn’t have to back out. She didn’t have to crush Sheila. She didn’t have to break Reid’s heart. These notions sparked without permission between the fits of crying and the pangs of wanting his hand back in hers, and on their heels, she wrestled the knowledge of how awful these thoughts made her.

His mother’s pale face shook with rage at the slow track of official involvement in those first few days. The phone never stopped ringing, and the parade of well-wishers and do-gooders kept up an industrious buzz that felt nothing like progress.

When they came with news of Reid’s car, the mood shifted. The civilians retreated in discomfort with hollow offers of “anything we can do,” and the police presence increased threefold. No one said it for days, but everyone knew that Reid was dead. The investigation flowered in false leads, then collapsed under the ponderous weight of nothing to go on.

The milestones of time accumulated—a week, and the crying was still rampant, as were the kind prompts not to lose hope; a month, and the phone rang much less, but still occasionally with callers who didn’t realize that he was gone; a year, and a picture of Reid went into the casket with Sheila and rested in a marked grave in a churchyard. His smiling likeness was tucked away in the crook of a dead woman’s arm, and also at some point into the back of the telephone book, then finally into a cupboard drawer in the kitchen, while his body lay under hastily strewn and unconsecrated ground, tapped into place with a garden shovel on a moonlit night by a man that none of the rest of them knew.

3

They say God gives us no more than we can handle. That is either an horrendous lie or the loosest possible definition of the word handle. Looking down the length of himself, Jason couldn’t understand how everything still appeared attached. His mind had jittered his fingers off his hands and his hands off his wrists a dozen times since he’d stalled over making the call, the undialed phone going warm and heavy in his palm. He did it anyway, of course. A few extra minutes of anonymity wasn’t worth the stage fright, trembling there under Calvin’s mournful encouragement to involve the authorities. “Call the police, Mr. Getty. They’ll know what to do.”

So he sat alone at the table, watching through the dining-room window for the unavoidable squad car to turn down the street and ruin his life.

The fever flush that had seeped all the way into his collar still burned in his cheeks. Jason hated blushing; hated that he couldn’t keep from doing it; and, most of all, hated that it made him five years old again—every time—for just an instant.

The first blush he could ever remember had lit him up in the lobby of his parents’ bank. His feet had dangled well above the floor as he sat in a row of waiting chairs, watching through the glass panels in the door opposite him. His mother’s stiff back and the manager’s bald head, nodding, then shaking, held him transfixed like the TV westerns he watched with his father, but didn’t understand.

“Hey there.” The pretty teller with the biggest, palest blue eyes he’d ever seen crouched to meet his level. “You’re being so good, little guy, waiting out here this long. Want a sucker?” She fanned a rainbow of candy in front of his face. “What color do you like?”

“Red.”

“What’s your name?” Her eyelids flashed pearlescent blue to match the irises as she blinked.

“Jason Bradford Getty.”

“Well, there’s a mouthful. Can I just call you ‘JB’?” Jason nodded, dumbstruck in the grip of peppermint breath and sparkling arctic eyes. “Swell,” she said, and plucked the red one from the bouquet, but offered the rest in her other hand as well. “Hey JB, want to take the rest of these home? Maybe share them with your brothers and sisters when they get home from school?”

“Don’t have any.”

“Oh yeah? Same here. We match, JB, you and me. I’m an only child, too.”

Looking into her smiling eyes, a feeling welled in his chest, a feeling that Jason would remember at intervals for the rest of his life, like a weighted balloon rising up through him and pulling back down all at the same time. A hope on a doubt. A reach and a recoil. Yes, but maybe no.

“Uh-huh.” His eyes stung from not blinking out of her spell. His voice went tiny. “Very only.”

“Very only? You mean, very lonely?”

“I don’t—” He almost understood what he’d got wrong and “almost” itched like the dickens. It blazed in his cheeks and heated up the back of his neck. He buried his face in his mother’s coat, which lay draped over the arm of the chair.

“Awwww, you sweet thing.” She laughed softly and ruffled his hair.

He felt her there, waiting for him to look up, but he outlasted her. “Okay,” she whispered. “Bye, bye, little Mr. Very Only. You take care, now.”

The bank teller had left him all the suckers. Jason left them all under the seat cushion.

Now, he blushed when he counted out exact change. He blushed trying to untangle himself from telemarketers. He blushed at the urinal, which was completely stupid. And then sometimes, he wouldn’t. There had been times he would have guessed his face would have flat-out ignited that it simply hadn’t. The first time he asked Patty for a ride home. The time he’d talked off a speeding ticket after having had three beers and more devotion to the beat of the song on the radio than to the numbers on the road sign.

Sometimes that climbing sense of promise didn’t feel lousy. Sometimes it straightened his spine. In those moments, Jason almost understood the mechanism; almost knew what it would take to cut the anchor and rise with the hope.

“Almost,” as always, itched like the dickens.

Authorities. Even in the midst of his lava-faced personal earthquake, a kernel of anger glowed at the presumption of the word authority. What did some smug, barely-able-to-grow-a-mustache infant know about getting pushed and pushed and then pushed just a little too far? Nothing, that’s what. They all ducked behind a tin badge and a gun belt as fast as the academy could churn them out. No one harassed them. No one stalked and taunted. No one found their weakest link and nudged and twisted and—

And there it was. The blue-and-white sedan pulled into view with its boxy band of roof lights dormant. Jason was surprised at the lack of fanfare, but then again, no amount of whooping, flashing urgency was going to do the guy in the garden a lick of good. Who was that guy anyway? The only reason Jason’s anxious mind hadn’t churned itself to butter and his tremors hadn’t tipped him right out of his chair was the distraction of the skeleton in the mulch bed.

He rode the slithering waves of horror at the thought of the dead guy—God, what if it was a woman?—rotting away under his bedroom window. He felt tainted and violated, angry that someone would have the audacity to put a body in a place like that, so close to a house, to a guy’s bedroom, for God’s sake. He’d been sleeping eight feet from a corpse the whole time. Offended in the extreme, his mind skittered around the elephant in the middle of his psyche. Comparing his own attention to detail in these sorts of matters was a bit more than Jason could face at the moment.

The implied insult of Calvin’s declining Jason’s invitation to wait in the house annoyed him, too. Jason felt abandoned and miffed at the workers’ avoidance as they snatched their tools from the lawn and scurried back to the truck to huddle and smoke and flick their eyes in his direction. They had no reason to be suspicious of him. For heaven’s sake, the skull they’d found was bare bones. That takes time. A lot of time. He’d only been here …

“Almost two years,” Jason answered.

“I see.” The officer made a makeshift desk of the trunk lid of the cruiser and scribbled the tidbit alongside the rest of the see-Spot-run basics. He straightened up and stretched, then hooked his thumbs over his belt, fingers just brushing his sidearm to the right and his Taser to the left. Jason assumed this stance was taught at the academy to draw attention to the belt of authority. The cop sucked his teeth and nodded. “I went ahead and put in a call. All we need is a detective and a crime-scene team since those are human remains you’ve got there and I’m satisfied that this isn’t”—the cop’s eyes slid appraisingly over the yard and its owner—“a fresh crime scene.”

“Well, I already told them that when I called and they sent you.” Jason stifled the bristling indignation at being presumed an idiot.

The responding chuckle was good-natured with an undercurrent of exasperation. The officer nodded to the back of the house, where Mrs. Truesdell’s mutt snuffled along the tree line. “With the calls we get? You’d think we ought to send out a SWAT team every time some hound kicks up a bone.”

The both of them watched the dog, one of them casually, and the other one not nearly so. Jason’s legs doubled in weight and threatened to buckle as his guts twisted into a leaden lump. The cop didn’t seem to notice. He opened the trunk and rummaged through a black nylon bag. “Yeah, last fall there was a little kid that went missing and we got a call from some guy in North County just swearin’ up and down that he’d found what was left of him. One look and I seen it was a broke fox skull, just as plain as day. I mean, that kid was nine years old, for cripes’ sake, and he’d only been gone a week. You’d think anyone could tell the difference between a weathered, old fox skull and a … well, anyway … it was nothin’. Just a custody thing.” Yellow barricade tape in hand, the cop turned back to Jason. “I’m just gonna go seal this off while we wait, okay?”

“Sure.” Jason’s head bobbled up and down. “Fine. Right.” His stride was uneven as he adjusted his speed to keep a reasonable distance from the cop’s backside and still maintain the security of having him close, of being able to distract him from any roving curiosity.

At the edge of the mulch bed, the officer stopped in a jangle of keys and creak of leather. Jason stopped, too—about ten inches off the policeman’s elbow, practically close enough to kiss. Jason lurched a quick step backward after having been scanned head to toe under a set of raised eyebrows.

“You don’t have to stay out here, you know,” the officer said with more recommendation than sympathy in his voice. “I’d understand if it’s uncomfortable for you.” The cop looked down at the skull with its blanket of dirt pulled up to its nose like someone afraid of the dark.

Jason followed his gaze and shuddered. “That’s not making me uncomfortable.” Mrs. Truesdell’s dog trotted through their peripheral vision. Jason shifted his position in front of the taller man and willed himself a wall between the cop and his backyard.

The policeman set to the task of roping off a perimeter with the blaring yellow plastic strip wound and tied to the odd branch and gutter. Jason watched over him with unseeing eyes as the cop pinched off loop after garish loop of banner tape. Jason’s focus had turned inward, viewing in the theater of his mind the scenes that would play out between now and the time that the damned authorities would take away these bones and leave him be—or drag him, cuffed and weeping, from his quiet life tarnished with one incident of madness.

A sharp bark wrenched him from his trance and sent barbs of fear pricking into his armpits and groin. Mrs. Truesdell’s dog barked a second volley, and Jason flinched again, even though it was only an announcing call at the arrival of a car, not the excited yip of discovery. Another longish blob of a sedan, this one marked by its government-issue blandness, pulled up to the curb behind the patrol car.

Jason evaluated his opponent as the man introduced himself to the members of the Dearborn’s crew still sulking in their work truck, glad-handing in a politician’s ploy to set them at ease. This was the man to beat. This was the guy who had to believe him or, better yet, give him no consideration at all. Jason was not adept at fielding adversaries, but he was a crackerjack wallflower. Fear made a grim brute of the troll stalking across the front yard, but reality presented a short, trim fellow in a crisp golf shirt and khaki slacks. He extended a hand to Jason, complemented by a perfectly tempered smile to go with it: professional, comforting, not inappropriately friendly given the circumstances. It was the smile of a man with the casual clarity of being right in his purpose, right in his conscience, and right in his “authority.” Jason’s spine sagged into the space generally reserved for his stomach. The battle felt lost before it had begun.

“Mr. Getty, I’m Tim Bayard.” Detective Bayard’s hand was warm and dry, and Jason did his best to calculate the correct number of pumps required to convey his innocent-bystander status. The detective somehow fashioned a neutral pleasantry from the worst thing that Jason could currently imagine: “Some day you’re having, huh?”

“I’ll say.” Jason’s mouth twitched into an admirable best shot at an agreeable smile.

“Well, why don’t you show me around and we’ll figure out where to go from there.”

“So, what do you know about the previous occupants?” Bayard asked.

“Nothing. I bought the place from a Realtor. She said it had been empty for a little while,” said Jason.

“Did they leave anything behind? Boxes, papers, anything?” Back in the kitchen, Detective Bayard sipped from a glass of ice water as Jason shook his head. The detective’s eyes roamed his notes, but Jason suspected that it was only for show, a sort of dimming and raising of the lights before the curtain call. Bayard drew a deep, preparatory breath. “Okay. Well. I’m going to call in a team to retrieve the remains. That’s the first thing. We need to know who got themselves buried out here.” Bayard drank again, but Jason took it as only pacing the pounce. “Mr. Getty, I’d like to get your permission to search the house.”

“There’s nothing here.” It had zipped out too quickly and more than a bit flat, and Jason had to replay it in his head to assess the damage.

“You’re likely right. And I am sorry for the intrusion. We’ll be as quick as we can.”

“I mean … it’s just … It’s my house now. And my things.”

“If you’d feel better about it, I can get a warrant, and, of course, you may certainly involve an attorney at any time.”

It was the oldest tableau in police drama. The inevitable question. That it had been made innocent by legal necessity did nothing for the one on the receiving end. All protestations of protocol aside, if an attorney was called for, the unspoken-by-law implication was What do you have to hide?

Jason stalled. “The people before me really didn’t leave anything. Just dust.”

Bayard shrugged. “All the same, I can’t say I’ve checked it out if I haven’t checked it out. You know, attics, crawl spaces, loose floorboards. I’m sorry for the intrusion, but there is every good chance we’re dealing with a homicide. It may very well have happened in this house.” Bayard continued with an I-feel-your-pain smile that was really just tightly pressed lips stretched back into his cheeks. “Bad luck you ended up sitting on a crime scene. We really do appreciate your cooperation.”

Cooperation was actually the last thing on Jason Getty’s mind. The months of distance from the October night that he’d sweated and ached through didn’t exist anymore. He was back in his living room, betrayed, a fool. Very only, indeed. Hollowed out, trembling with rage and humiliation at a torrent of threats and gibes. The taunts rang in his ears, his chest and back throbbed where the heel of a strong hand had slammed him into the doorframe, the aftershock ricocheting through his ribs. There was a blank, red space in his memory and then a sound like a bell wrapped in felt, dully clanking. There were grunts of exertion and a groan of pain cut short. Cracking plastic and cracking—

“Mr. Getty?”

Jason sighed. “Sorry.” He swallowed the last of his vision: his knuckles sinking into a wet crimson breach under a tangle of dark hair. He pinched the bridge of his nose. “It’s just a lot for a Sunday morning.”

“I know. And I am sorry.” Bayard stood and gathered his things. “I’m going to head out to the car and call in for the people I need. May I go ahead and get you to sign a consent form, or should I have them start the process for a search warrant?” It felt as if Bayard made sure to catch Jason’s eyes dead-on. “Really, it’s no problem, either way.”

Bayard would have his ramble through Jason’s house, and the twinkle in the detective’s damned eye was the period on that particular sentence. Pinned in the standoff, neutral and professional as it was, Jason’s heart squirmed hard under his breastbone, and the fleeting hope that he was dying of a heart attack elbowed around in the queue of pressing issues at hand. “No, that’s okay. You can come in and look around.”

Bayard smiled, but his eyes stayed strong on Jason’s. “Thanks. And the lawyer? I can give you time to look one up and get him over here.”

Jason wasn’t sure he could take this. He toyed with the image of falling to his knees, confessing all, and baptizing Bayard’s loafers in a flood of contrite tears. Except that would have been a lie and he wasn’t quite sure he’d be able to pull it off. He wasn’t one bit sorry that he’d killed that son of a bitch.

Mostly he avoided thinking about it—the actual killing and that the world was short one human being because of Jason Getty. The decision to hide the evidence on his property was an enormous regret, of course, especially now. But when the torture of the rest of the problem fell away, as it occasionally did, and the bottom line stared back at him, Jason tingled with triumph. There was horror and revulsion and a crippling fear of getting caught, but there was also satisfaction. He’d stopped it. He’d shut that vile mouth once and for all and wiped the smug smile off his lousy face. He’d seen that bastard’s blood on his own hands.

“Really, if you don’t have anyone in mind, or”—Bayard left a bit of important dead air on either side of a good-natured chuckle—“keep a legal eagle on retainer, the phone book’s got a whole page of good local lawyers with great reputations for making sure we dot all our i’s and everything.”

“I don’t see that I need a lawyer right now.”

Jason had said it without a quiver. He hadn’t blinked or swallowed hard. He hadn’t shifted his feet and certainly not his eyes from Bayard’s. He’d even managed a comfortable smile. He should have been proud of the performance. But something had changed. Maybe the ambient temperature in the space between the two men had dropped a degree or a cloud had passed over the sun. Something was definitely, minutely altered.

“If you’re going to have one, Mr. Getty, I’d say better sooner than later.”

In for a penny, in for a pound. “There’s no reason to, Detective Bayard. I haven’t done anything wrong.”

4

Detective Bayard pretended not to notice the inch-wide gap in the bedroom curtain that winked shut whenever he turned toward the house. But Tim Bayard noticed everything. It drove his seventeen-year-old daughter nuts. The twitching curtain and the unseen hand that worked it shouldn’t have bothered him really. Getty’s behavior wasn’t all that strange. Anyone with a skeleton in his mulch bed and a crime-scene unit crawling all over his side yard would be drawn, morbidly, to the view. That was probably all there was to it. Probably.

Bayard cornered the lead tech out of sight of the window and its restless draperies. “So, Lyle, what’ve you got?”

“What do you mean?” Carter County’s lead crime-scene investigator was a man of impossible-to-determine age in that his hair was salted to make the pepper incidental, but his face was as unlined as a college freshman’s. His sharply pressed collar gleamed against its color-coordinated sport coat, and it all looked much more suited to nightclub prowling than it did to crime-scene mucking. Bayard sometimes wondered what excuses played out to Lyle’s dry cleaner, foul as his laundry was likely to be.

“I mean, what do you know?” Bayard’s eyes tossed an arc of indicationover his left shoulder toward the action in the flower bed. “What do you think?”

“You’re kidding, right?” Lyle scowled at his watch. “I’ve only been here, like, forty-four minutes.”

“Yeah, and you’ve spent forty-one of those minutes taking notes and three minutes scratching your arm.”

Lyle gaped at Bayard. “What is wrong with you? You don’t have anything better to do than to stand around staring at me? I’ve got a bug bite. It itches. Get a hobby, Tim.”

“I just want to know what your first impressions are. What’s in your notes?” Bayard craned his neck to peer at what Lyle had been writing.

Lyle slapped his clipboard to safety against his chest. “It’s a letter to my girlfriend.”

“I’m gonna tell your wife.”

Lyle chuckled. “I know we don’t get bodies very often, but try not to drool. It’s disturbing.” Detective Bayard wasn’t going away. “Tim, I don’t know anything about him yet.” He turned back to the site.

“But you do know it’s a him.”

“Yeah, I think so. He’s got a very manly brow.”

“‘Manly brow’?” Bayard scratched the back of his head and grinned. “You sounded just a little turned on right then, sport. You know that, right?”

Lyle tucked his tongue into his cheek and nodded in mild agreement. “You caught me. It was a letter to my boyfriend. Can I get back to work now?”

Bayard snagged Lyle’s sleeve before he could drift back into the sight line of the window. The idea of Getty peering out from the shadowed bedroom, watching them and straining to lip-read, tickled unpleasantly at the suspicious part of Tim’s imagination. “How long has the body been there?”

“Good God!” said Lyle. “I don’t know! We haven’t even taken the bones out yet.”

“Less than two years?”

Lyle’s mouth turned down in academic certainty. “Nah, no way.”

“Are you sure?”

“No. How can I be sure of anything anytime soon when I’m talking to you instead of doing what I’m supposed to be doing?”

Bayard scanned the taped-off plot. “I’m just thinking out loud here, Lyle.”

“Hope that’s working out for you. For me? Not so much.” Lyle’s gaze, however, followed the cop’s, and both men’s moment of silence whirred with purpose.

Lyle roused first from his musing. “But assuming he went in whole, that skeleton’s too clean. I mean, we’ve got tons of work to do—you know how long these things take. The tests and all that will be out for weeks—but I’m thinking at least three or four years.”

Math and the consequences of speculation clicked away in air between them. “Do not write that down anywhere,” Lyle added.

Bayard pressed his lips together and drifted into a contemplative headspace. “Hmmm.”

Lyle watched him slip into distraction, entertained. He leaned in to stage-whisper, “Do you really get paid for that?”

“Huh?”

“All these years, do they really fork out cash for you to look serious and make thinking noises?”

“You know, I’m gonna make sure I’m on your next review panel,” Bayard said.

Lyle snorted and turned back to his work.

Bayard called after him, “Hey! Let me know as soon as you find anything.”

“As opposed to what? I don’t start my reports, ‘Dear Diary, I discovered the most interesting thing today …’ Gimme a break, Bayard.”

The curb was quickly stacking up with an official-looking traffic jam. Bayard trotted over to a monstrous pickup squeezing into the last space that could still loosely be considered “in front” of Jason’s house. “You’re quick!” Bayard called.

The man behind the wheel filled up the cab a time and a half the allotted driver’s space. A sleek-faced dog in the passenger seat flicked attention to every landmark as fast as its head could swivel. But the dog drew even more notice than it normally would because of the pointy, foil party hat on its head. It sent starbursts zinging off through the windshield with every movement.

“What the hell?” Tim cocked his thumb at the dog, wagging its greeting to him. “What did she do to deserve that?”

“What? It’s her birthday.” The two men watched the dog, which was not minding at all that the sparkling dunce cap had slipped down over one ear. “You caught me just on the way out for party supplies. This better be good.”

Such a scene has an excitement that only cops can appreciate; the secret ingredient that separates those who like to watch cop shows from those who want to live them. It comes with a tight smile and a complementary tightening in the gut. “It’s good,” Tim confirmed. “Body in the mulch bed.”

“You peg him for it?” The big man ticked a discreet nod to the front door of the house where Jason stood shuffling, hands squirming deep in his pockets. His brow mimicked his lips in a parallel set of worried crinkles that left him looking lost somewhere between a pout and a dire need for a toilet.

Bayard’s flickered glance was equally camouflaged. “Nah. Not unless Lyle is way off.”

“That’ll be the day.”

“Right. Anyway, thanks for not making me wait around, Ford.”

Ford Watts climbed out of the truck that perpetuated the corny joke he’d floated for going on fifty years. He’d finagled his driver’s training at age fourteen and, ever since, would not be caught behind the wheel of anything other than a namesake vehicle. Not, at the very least, without substantial grousing. When the department had gone turncoat and switched to Chevy for a stint in the eighties, everyone from the receptionist to the chief had reaped an earful from Ford Watts. This year’s Ford was a deep-red, double-cab pickup.

And how he loved his cars, buffing and dabbing in devotion to the showroom glow, and always eyeing the sky for birds of ill intent. The truck bounced on its springs as he climbed out, and although the season had been wet and chilly, Ford was as rosy and shiny as the finish on the polished cab. He dwarfed his human company by about the same proportion that his truck made the other cars look like toys.

Bayard briefed him on the basics as they crossed to the house. Jason had slunk back inside at the slamming of the truck door, so they were alone on the stoop while Bayard sketched out the simple strategy. “So, I’m going to take Valerie from Lyle’s team with me and we’ll have a first look around, while you get the search consent forms signed. You know, ask him all the same stuff I did. Just keep him outta my hair for a little while.”

“You brought me out here on a Sunday to babysit?” Ford grumped from his full altitude, an impressive nine inches above Bayard’s head, without somehow achieving the intimidation he was trying for.

“I could’ve called someone else. I thought you’d be interested.”

“It’s Tessa’s birthday,” Ford said.

Bayard pulled an inspired face, all high eyebrows and pursed lips. “Oooo! Maybe you should go get her, trot her around a little.”