Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

Karl wakes up in a locked room, a prisoner once again. But this unfamiliar place is no penitentiary. And this time he volunteered to be here. A tragic accident took everything that was dear to Albert. Now everybody's favourite twin sits in his wheelchair and contemplates the ultimate sin. Dagmar was taken in by the church as a baby and has grown into a young woman with a ferocious appetite – and it's not for food. Tobias is the other twin, the also-ran whose greatest talent lies in impersonating his brother. Tobias' skills are less developed when it comes to killing. But make no mistake – he'll catch on… Four different people. Four different stories. One murderer. Maybe their lifelines crossed years ago.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 600

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

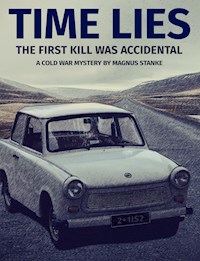

Times Lies

By

Magnus Stanke

Copyright

© Magnus Stanke, 2016

Prologue

On the morning of the last day of her life, Sabine Schneider contemplated the nature of men. The cruelty of chance would have been a more pertinent subject to ponder, but it wouldn’t have changed anything. There were no otherworldly warning signs of her impending doom as she made her rounds in the sleepy village of Eschershausen, the peaceful town she called home— or if there were, she didn’t see them.

Sabine had a thirst for philosophical deliberation and a tendency to get lost on tangents. She believed that human nature could be studied anywhere in the world, even while delivering the post in a four-thousand-soul village where nothing ever happened.

Take this here street, the Hüschebrink, for example. What does it say about the nature of men?

The most prominent building, number twenty-one, right on top of the rise and the last house before the graveyard, dated from before the First World War. It was a mansion, really. For the last ten years or so, since the early 1970s, it had belonged to one of the richest families in the village who restored it to its former glory. Then, three-and-a-half years ago, tragedy struck, resulting in the deaths of the wife and child of the occupant. After that, most of the wooden shutters had been nailed down and some of the windows totally bricked up so that the building itself had taken on a sombre look.

Now whenever Sabine climbed the hedge-lined, tiled steps that led up to its entrance to deliver packages that didn’t fit into the post box by the street she couldn’t help feeling that the house itself was in mourning.

On this particular day there was no need to walk all the way to the door. The two envelopes fit perfectly well into the thin slot, but she felt strongly that she could somehow connect this building metaphorically to her ruminations if only she got a little closer.

Nobody saw her as she started up the path to the house.

That’s it, she thought. The twins, Albert and Tobias Hoffmann, surviving widower of said tragedy and his identical brother, respectively — the current occupants of twenty-one. They looked like clones, totally identical, yet Sabine could easily tell them apart; not because of their body language or demeanour, but because…well, when she had Albert in front of her there was a faint tingle in her groin. Okay, no, that wasn’t good enough. Female intuition didn’t cut it these days, not in 1982. Still, there was something about them that troubled and fascinated her in equal measure, philosophically speaking.

Nothing warned her of what was to come — no sixth sense, no female intuition, no eerie wind whistling through the nearby poplar trees as she approached.

The evergreen yew hedge that ran around the property was high enough to conceal most of the garden even from the path leading to the front door. Only as she got closer did she notice something vaguely unusual: the window to the dining room was open. Inside were two men, one carrying the other over his shoulder. The twins, apparently.

Sabine couldn’t remember seeing Albert out of his wheelchair since the accident, not because he was actually paralysed, but because he never got over his loss, had become a recluse and refused to walk. A pity, really. Albert had always been the nicer twin. His confident smile and worldly air had made him incredibly well-liked and the object of widespread swooning. Carrying him was undoubtedly Tobias, who, though indistinguishable from his twin in every other way, was forever — well, less nice, less likeable. It wasn’t that Tobias was nasty or mean, he was just…less. They were different inside even if they looked the same on the surface.

What came first, looks or character? Sabine mused. Did Albert turn out to be the nicer person because he looked subtly nicer or was it the other way round? Did people treat Tobias differently and therefore he became a less likeable person? If only she could get to know them a little better, Albert Hoffmann especially. Given half a chance she could bring the famous smile back to his sad, blue eyes. She could reignite it, make it shine again.

Well, maybe.

The stone steps ended a couple of metres from the entrance, and with them the hedge. Only now did Sabine see Albert sitting in his wheelchair outside, on the left of the house, an area that had until now been a blind spot for her. He was dozing, an open newspaper across his legs and a cup of coffee on the wooden table next to him.

‘Good morning, Herr Hoffmann,’ she said, hardly audibly in case he was asleep.

They were the last words she ever spoke.

While Albert didn’t stir, Sabine’s arrival had caught Tobias’ attention inside the house. He spotted her through the open window in the salon, dropped the man he was carrying over his shoulder and disappeared from sight. Seconds later, the heavy wood panelled front door opened soundlessly from the inside.

The last thoughts that went through Sabine’s mind as she turned her head and saw Tobias in front of her — closer than expected, his hands behind his back, his breath rattling as though he had just run a marathon — were this: if that human bundle on Tobias Hoffmann’s shoulders seconds earlier wasn’t Albert, who exactly had he been carrying? This was Tobias in front of her, wasn’t it? He almost smiled like…

Then his left hand made a swift upwards movement and something stabbed her in the heart.

It went dark and Sabine Schneider was dead before her body hit the gravel.

Part One

1982

Chapter One

It is daytime, probably. He is aware he has been lying there for quite some time, hours maybe, but the urge to do anything about it — to wake up properly, to get up and move around and inspect his environs — is weaker than the one that tells him to rest some more; no need to get out of bed just yet. The cot or whatever it is feels tolerable. He isn’t cold or wet, he doesn’t think he has pissed himself and he is in no pain.

No, wherever he is, it is all right, no hurry to do anything about it. Knowledge, clinical, precise knowledge of self or others never does any good to anyone. He knows this from experience.

The cotton in his head is different from a straight hangover, that much is clear. Absent is the reassuring thirst of the hair-of-the-dog-that-bit-you that can be quenched by continuing to drink. No, this mist will settle sooner or later, but inevitably the headache will sunder his head in two, probably not much later than whenever he decides to get out of bed. The less he thinks about it the longer he’ll be pain free. Whatever it is that has brought on this sensation is most likely chemical, some kind of drug, judging by the bitter taste and the film on his tongue.

After a while, and against his better judgement, Karl sits up and looks around him. Memories, conflicting and troubling, struggle to come to the foreground despite his best efforts.

The room he is in isn’t exactly small. It’s much bigger and nicer than the prison cells he has slept in. Hell, it’s nicer than most of the flats he’s lived in. The furniture is BRD style, solid wood, a table, a chair, a cabinet; none of that cheap linoleum crap they have on the Other Side. There is also a fridge, a hot plate, even a sink, a shower and a toilet and walls, clean walls, undisturbed wallpaper with red rhomboids, no signs of damp or lurid prison drawings, no peeling in the corners, no crumbling.

The only tangible reminder that Karl is indeed a prisoner of some sort is the fact that there is no window in the room and that the sturdy metal door is without a handle on this side.

Still, nobody raises him, hassles him, plays marching music to prevent him from sleeping. There have been no beatings that he can remember – a quick body check confirms he has no new bruises and, now that he thinks about it, he also notices there aren’t any unpleasant noises, no screaming wardens or rioting prisoners, no humming electricity or fluorescent lights. In fact, there are no sounds at all.

Karl looks around some more and finds the source of whatever brightness there is in the room. It is a simple domestic night lamp on the table, the glow diffused by an off-white round screen. It is plugged into a wall socket under the table. Obviously they don’t expect him to use the cord as a weapon against the wardens or to hang himself with, nor are they worried he will use the broken glass of the light bulb to cut himself or anybody else.

They just aren’t worried. Well, if they aren’t why should he be?

Reassured, Karl lies back down again. These jailors, whoever they are, are certainly unlike any others he has encountered on either side of the curtain, but it could be a mistake to misinterpret their kindness as weakness. In all likelihood the contrary is closer to the truth.

The silence, though, is something else. The silence, the total absence of sound, is something he will have to get used to. Where on earth is it ever this quiet, quiet enough to listen to his own breathing, quiet enough to make him aware of his own beating heart?

Exhausted now by all the brain activity, Karl closes his eyes and dozes off again.

He wakes startled only minutes later. He sits up and looks around, more lucid than before, alert, vaguely remembering his earlier thoughts about being safely imprisoned and cocooned in silence. His toes find the ground and he struggles to his feet, slowly approaching the wall to listen. Nothing. No sounds at all.

His memory starts to come back and he pictures his jailor, that ridiculous individual who claims not to belong to the Stasi. The deductions begin. He must be still in the West, in the capitalist part of Germany, locked in a room in a private house. This conclusion is based on the fact that even the larger holding cells he has slept in since crossing over to this side of the border, in the villages where local policemen scooped him up from outside some Kneipe, drunk into oblivion, have always been smaller and colder than this, and none of the Stasi lock ups he has been in resemble this place even remotely.

What does that amount to? He can’t quite work out whether he is here against his will or voluntarily. Suppose the man didn’t lie – Karl quietly recalls the scene that started all this. He remembers being released from yet another local caboose, walking the walk of shame towards the nearest bus shelter like he had done at least a dozen times before, already thinking about how to raise a bit of cash for his next bender. Was there anything else he could sell? Wasn’t the monthly money order due soon?

Then a green car with a rental sticker, an Audi or a Ford, stopped next to him. The driver opened the door on the passenger side and beckoned him to climb in.

‘Don’t worry, I won’t bite. I’ll drive you home, to your apartment. We talk a little, no strings,’ he said.

Karl hesitated. The man had said nothing that concerned him. He wasn’t worried about being bitten, but there was nothing to talk about, either. On the other hand, it was cold, he was freezing in his damp, pale denim jacket, and the wait for the next bus could be half an hour or more.

‘Look,’ said the man. ‘I’m not queer and I’m not trying to get you to do a…job, if that’s what you’re thinking.’

Karl was still hesitant. He said, ‘Are you Stasi?’

The man laughed, relieved. That thought hadn’t even crossed his mind. He shook his head and the seat squeaked under him.

‘No, I’m not Stasi, nor am I with the BND. In fact and for the record, I’m not with a secret service of any persuasion. FBI, KGB — all of the above I’m not.’

He laughed some more and shook his head, a little too energetically. The seat made the high-pitched noise again.

Until then Karl had barely glimpsed him, but now something caught his eye. The man’s hair moved. That big curly thing on his head was a rug. The beard was probably false too, and the nose and those big sunglasses on this grim winter’s day. Whoever he was, he did not want to be recognised by Karl. Hence he wasn’t planning on killing him.

Reassured, Karl climbed into the car while the man fixed his wig.

The voice sounded familiar, though, didn’t it? Well, it should have. Then again it could have been disguised like the rest of him. They had technology for almost anything, those people from the West. Karl now saw that the man had a big belly that almost touched the steering wheel and that his hands were gloved.

When they drove off, the man glanced in his rear-view mirror once, and again a little later and a third time after a minute or so.

‘It’s probably safe to assume that those friends of yours, the ones you mentioned earlier – State Security of the German Democratic Republic – are behind us. Don’t turn around. Here, use this,’ he said.

The man adjusted the rear-view mirror so that Karl could look without being seen. There was no doubt. A conspicuous car followed at a certain distance, two men in grey overcoats inside. Müller and Schmidt, maybe? Was it possible the Stasi had caught up with Karl? The Volvo was too far away to recognise the faces, but he instinctively felt that the man next to him was more trustworthy than the two men that followed them.

‘We’ll worry about them later. For now, have a look at this,’ the man said, and then pulled the mirror back into position and leaned over to open the glove compartment. ‘In there,’ he said, gesturing with his gloved hand.

At last Karl did look, stretched out his arm and slid his hand into the opening. At first all he felt were maps and a piece of cloth, a window wiper.

‘It’s a small box, a pill case,’ the man said.

Karl rummaged some more and then he pulled it out. What was this, a joke? Was he proposing? The case looked like it contained jewellery of some sort, possibly a wedding ring.

‘Open it.’

Karl did as he was told while the man steered the car towards the centre of the town. Inside the case there was a small, oval shaped white pill.

Karl didn’t ask. He knew in time the man would volunteer all the pertinent information. Only that, no more. The man seemed sure of what he wanted and couldn’t be coaxed into saying any more than he planned – that much was apparent.

Well, neither could Karl.

Both men waited for the other to break the silence. Karl won in this instance.

‘Okay, here’s the deal. I drop you at your flat and drive around the block to lose those clowns behind us. I’m back in fifteen minutes, plenty of time for you to pick up your stuff –well, your toothbrush. You don’t own much else. I stop the car and you get in and swallow the pill. No questions, no explanations. Just this: life as you know it will be over. Something better awaits you on the other side. If you do as you’re told you’ll end up comfortably rich. And that’s a promise.’

Karl studied the man while he spoke in order to grasp the whole meaning of his words, but his voice was motionless and his face might as well have been a mask – what he saw was less than met the eye.

Karl wanted to ask what would happen if he didn’t come back and get into the car, didn’t choose to swallow the pill, but the answer was all too obvious. He would continue slipping like before. He’d resume the unstoppable decline that had started when he was set free into the Golden West, object of a ransom deal between the two Germanys, a political prisoner of the East sold to the West for a handful of deutsche marks, the hard currency the communists craved so badly due to their failing economy.

It was true, Karl didn’t like it in the West, but he knew he could never go back east. If he didn’t take his chances with the strange man he would continue his downward spiral until he really hit rock bottom. Eventually he would probably let himself be recruited by the two guys in the car behind to spy for the Workers’ and Farmers’ State he used to call home.

Neither of them said a word until they reached the Mozartstrasse where Karl rented a small apartment. He was behind on the rent and would have to act fast if he wanted to avoid a confrontation with the landlord, if he hadn’t changed the locks already. It didn’t matter. There was nothing in the flat Karl wanted. Not a thing.

He made his decision.

‘I don’t need fifteen minutes. See if you can shake them in less,’ Karl said and got out of the car.

As he approached the dark building and unlocked the front door, the car pulled away from the curb into the traffic. Before the door fell shut behind him, he saw the grey Volvo follow. Karl dropped the keys to the floor and stepped back outside. There was no point even attempting to go back to the flat; there was nothing of value, nothing he cared to take with him, not even a toothbrush. His few garments were dirty and worn out, and he had his new passport on him.

Back on the pavement he leaned against the door and licked a cigarette with the tip of his tongue, pulled it past his pursed lips. The saliva helped to cool the smoke so it wouldn’t sting his lungs when he inhaled. It was an old trick he had learned back east to make the rough tobacco go down more easily and the habit had stayed with him. He could do with a drink while he waited. Maybe he should go upstairs after all, see if there wasn’t any vodka left somewhere.

Never mind that now. It wasn’t worth running into the landlady on the first floor or her husband on the second. Karl couldn’t be bothered having to explain, having to make excuses.

Would the man in the wig really come back? Light snow started to fall. He’d better come back, and quickly. Karl stepped from one foot onto the other. Cigarette smoke tasted great in cold weather, but the freezing air hurt his lungs and he knew smoking didn’t help his circulation. Before he flicked the butt away, he lit another cigarette from it. A little cold never killed no one.

When his current smoke was half gone the car reappeared and stopped beside him. Karl got in. The wig, beard and sunglasses looked friendlier now, almost seemed to smile at him.

‘I knew you’d come,’ the man said and there was nothing to say to that.

Before they joined the high street traffic, the man checked the rear-view mirror again and the hint of the smile disappeared. He hadn’t managed to shake the Stasi tail after all.

‘Don’t worry. By the time you wake up they will be long gone. Nothing to lose any sleep over. In your case, I mean that literally,’ the man said while he drove, the smirk back on his face.

He reached into his pocket and pulled out the jewellery case, placing it in Karl’s hand without taking his eyes off the traffic. Karl opened the box and lifted the pill gingerly with his dirty fingers.

‘One question before I do this,’ he said.

The man hesitated.

‘That wasn’t the deal. But you may as well ask. I’ll see what I can do, depending.’

‘Why me?’ Karl said.

‘For reasons I can’t go into, you are the chosen one, one in a million – no, one in eighty million and then some. I wouldn’t do this with anybody else. In the world. But you have to take my word for it for now. I can’t explain at this point.’

For the first time the man put feeling into his words, and Karl had no problem believing every one of them.

The man needed him. Karl felt less alone than he had for a very long time.

‘Do I know you from somewhere?’

‘We said one question only, but, for what it’s worth, I don’t think you’ll regret this. Honestly,’ the man said.

Karl placed the pill on his tongue.

‘Nor do I,’ he said and bit down.

The drug, whatever it was, worked as fast as lightning. The last thing Karl remembered was a chalky, bitter taste as the pill broke and dissolved on his tongue. Then there was nothing.

*

So he has given up his freedom — his Western freedom, mind you — to go into this voluntary incarceration. He should have his head examined, Karl thinks, not without mirth. If he told this to anybody back east they’d think him insane. He knows dozens of people who would give their right kidney to go west like he has done, and now here he is, imprisoned, giving himself over to a higher power of some sort yet again, albeit a phonily-disguised one, drugged and abandoned to boot.

And yet he isn’t worried, not now. After all, it wasn’t his choice to come over to the West, not directly. When his position in the East became untenable they, the Stasi, had packed him away into a prison on some drummed-up political charges with an exaggerated sentence — all pre-agreed between judge and prosecution before the trial in order to attract western media attention. The longer the sentence for political prisoners, the larger the ransom that could be extracted. It was complicated, but it worked more often than not, and it wasn’t nearly as complicated as what happened afterwards, when Karl was out on his own and expected to make the most of his new life. He had skills, a trade that should’ve stood him in good stead to find a job, he had freedom, he even had a little bit of spending money. Yet in his head things were so complicated, so convoluted and tangled that he preferred to stay inside, locked up in his head and now in this room, alone.

He started drinking, heavily. All those new choices he now had to make — he just couldn’t cope. Even the act of imbibing is complicated in the West. His money, his very own marks, could buy seven different kinds of vodka, eleven kinds of schnapps, five kinds of brandy, ten kinds of whisky and countless more types of beer and wine, just in a local supermarket. It was hopeless. Back home supermarkets only sold one brand of each beverage among otherwise often empty shelves. Absence of choice makes life easy. It’s a luxury the westerners don’t appreciate enough.

Where are empty shelves when he needs them most?

Karl looks at his hands. They are steady. He doesn’t know how long he has been out of prison, how many hours he has slept. What does surprise him is the fact that he feels no cravings for alcohol or cigarettes. How is this possible? Isn’t he a certified addict? Doesn’t his body force his brain to see mirages and hallucinations whenever it goes sober for any length of time? Where on earth are his damned DTs?

Funnily enough, he only needs alcohol when it’s freely available. If it’s there for the taking he just can’t resist. When he is in prison for any length of time he tends to forget about booze entirely. Being locked up again will provide a healthy break for his body, a sobering drought.

A thought shoots through his head and he gets up and opens the fridge.

Please don’t let there be any booze in there.

His prayers are answered. The refrigerator contains nothing but food: cheeses, ham, vegetables and meat. There are tomatoes and eggs and yoghurt and even some bananas and oranges, luxury items back home. That man, his jailor, obviously doesn’t want him to go hungry. In fact there are probably more vitamins in that fridge alone than Karl has eaten in any given year of his life. And he doesn’t even have to do anything for it, he can just help himself whenever he feels like it, doesn’t have to go into a shop that is full of wrong choices, every product telling him that it is better than the competitors’, pick me or go wrong. The absurdity of it – how can they all be right?

Well, for now he doesn’t need to worry about choices. They have been made for him. Karl discovers he is mightily hungry. He finds cooking oil and a skillet and fries a couple of eggs and ham which he eats with a slice of brown bread and cheese. He pours a glass of milk from a tetra pack and rummages through the cupboard he discovers in the corner between the wall and kitchen cabinet. It contains more food: flour, pasta, rice, cans of tuna, a tin of biscuits and some other things he doesn’t recognise.

Karl has never had much of sweet tooth, but today he decides he wants a biscuit with his glass of milk. It reminds him of home, of his mum, Mamochka, before she got sick, beaming whenever she managed to get the hard to come by ingredients to make real cookies – a bit of real butter and sugar, maybe an egg. He ate them for her sake more than for his own, couldn’t bring himself to say that he didn’t really like sweet things, crush her enthusiasm.

He takes a cookie from the tin, bites off a small piece and chews. It isn’t so bad, so he bites again, chomping off half the cookie this time. Before he can take a third bite, his arm drops and he is asleep.

When he wakes up the room is as before, except the food utensils have been cleared away and the washing up is done. Karl is lying on his bed and remembers the man with the wig and most of the thoughts that went through his head before he fell asleep.

The night lamp is on as before.

The silence invades him again.

How much time has passed is impossible to say. Time doesn’t matter here. It is almost as though it has stopped, is suspended in the room.

Karl gets up, uses the toilet, flushes and wonders briefly if his jailor might be watching.

‘Hello? Hello? Anybody there?’ he says towards the metal door.

He receives no reply.

‘Any chance of some privacy in here?’

He smiles. It is weird hearing his voice cut through the silence. It reverberates and echoes in his head long after the actual sound is gone, swallowed up by these clean, insulated walls.

He opens the fridge. It is as before, with two gaps where the eggs used to be. So much for the notion that it was a magic, capitalist refrigerator that could replenish itself, would never be empty like in the adverts. But no, this is no imperialist miracle machine. The food he has consumed is gone, the eggshells still in the bin. He doesn’t remember clearing away his plate or washing the skillet, yet both are clean and stored away. Come to think of it, it is also strange how he just fell asleep when he was eating the cookie and drinking the milk. Who put him to bed?

‘Where are you? Why don’t you talk to me?’ he says towards the door.

Nothing.

A disquieting thought strikes him. What if, once he has eaten everything in the fridge and in the cupboard, there is no more food for him? Would he just let Karl starve, the man with the wig? But no, he said he would make him wealthy. Surely he wouldn’t let him perish.

Karl strips off — he doesn’t care if anybody is watching or not — and steps into the shower. He opens the faucet and plays with the hot and cold until the mix is just right. He finds soap and lathers his body generously. While he cleans his genitals under the warm spray he becomes refreshingly aroused. Again, this is different from his previous prison experiences. In Cottbus, the last place in which he was an inmate in East Germany, rumour had it that the grub contained sodium nitrate, a ‘chemical chastity belt’ as the prisoners called it, to stop them from buggering each other. It kills all carnal desire outright. Karl didn’t have a single erection in the six months he spent there. Now he has some catching up to do.

Later, when he steps out of the shower and dries off, he is content. All this adds up to some kind of happiness. He made the right choice when he accepted that pill. That man means him no harm. Karl feels better than he has in a long time, and less alone. Somebody is watching over him. For the time being it is a one-way street, but so what? For the time being his conscience doesn’t bother him. Yes, he has done things on behalf of the Party that he is no longer proud of. He has spied on people, informed on potential dissidents, comrades who had forgotten about the purity of the socialist ideal. For many years it was the right thing to do according to the values he’d been brought up with. After all, the Party knows best. He knows this because history knows this. History teaches us that the Party knows better than us. The Party has been the only veritable, consistent opposition to the Great Evil of Fascism all the way back to 1933. The Party fought Hitler’s thugs at every turn, thereby displaying foresight that the Yanks, the Brits and the Frenchies lacked so badly back then — at least the politicians, who tolerated the Führer and even welcomed him and his anti-Semitic views right into their backyard. Appeasement, they called it.

Alas, the Party lost the first battle against the fascists, but they regrouped in Moscow, the lucky ones who weren’t thrown into concentration camps, that is. By 1945 the Party was back, and victorious. They helped liberate Germany, had known better all along than to follow the path to destruction. Of course the Party knew better, knows better to this very day. If they tell you not to read a certain book or watch West German TV, it is for the greater good. Those comrades who stray are like lost sheep. They need help to return to the flock before anything really bad can happen to them, before they can be corrupted irreparably.

At least that’s what Karl used to think, that he was doing his fellow men a favour, that he was protecting the pure from the depraved ways of the decadent West. But in time things changed, the world around Karl and inside of him. Doubt set in. And still, he continued to inform until it led to consequences he didn’t foresee, couldn’t have.

Surely the man with the wig knows all about his past and this is Karl’s reckoning, his way of cleansing his guilt. Yes, Karl understands that the reason he fully embraces his new lot is because he feels safe in the room. As long as he is locked up in here he can’t inflict any further harm, not on himself and not on anybody else. Maybe that’s why he’d een drinking so heavily before, and why the urge has now ceased altogether. This is his punishment, and as long as he stands it, accepts the verdict and the consequences, he is getting better, making amends.

I’ll be patient. I won’t run away and I won’t complain, he thinks.

‘You have my word for it. I understand now, ‘ he says towards the door, feeling gratitude for the man with the wig.

Then he just sits there and stares at infinity as represented by the rhomboid patterns on the wallpaper in front of him.

Time passes. Well, some time passes. Probably.

*

Karl’s sense of time vanishes almost at once. He’s been there before. Soon he doesn’t know if he has been in this room for hours or days. He eats when he feels hungry, goes to the toilet when necessary and showers when he feels dirty. When he is tired he lies down and closes his eyes. He only ever realises that he has slept when he wakes up from bad dreams. This happens frequently at first.

He tries to gauge the passage of time by assessing the diminishing quantity of food in the fridge. In between bouts of hunger he sits and thinks and listens. The silence around him is only interrupted by his breathing and his heartbeat, and he directs his hearing inward, tries to listen to the sounds of his digestive system, to the blood circulating in his veins and to the electric impulses called thoughts. For a long time he hears nothing. But he persists. He knows his body makes these sounds and that he will hear them if only he listens hard enough.

*

More time passes. Karl tries to detect the sound of his growing hair, beard and fingernails. He fails.

If time is an illusion in here, then cellular growth should stop too, shouldn’t it?

But it doesn’t. Time does pass. The proof is in his fingernails – they are longer than when he arrived. He can tell, especially because they have ceased to be dirty the way they used to be. Now, thanks to all the long showers, they are spotless. And the white half-moons at the tips of his fingers grow longer and longer.

Something else happens. He feels alone again, as though the man with the wig has abandoned him here after all, left him to languish in a room-sized grave. The fridge is nearly empty. The bread is long gone and only one egg remains; the milk went sour a while ago. Will his jailor show himself at last if he runs out of food entirely?

Not so fast. Best not to dwell upon events that you can’t control, Karl thinks, returning the last egg to the mould in the door of the refrigerator. The man will show himself when I’m ready for him, when I have earned him. There is plenty of dry food in the cupboard, rice and pasta, some canned goods. For now a biscuit will do.

Decision made. Cookie in hand, images of his childhood invade his stimulus-starved brain, images of the 1950s, when socialism was still taking hold in the recently founded German Democratic Republic. Pictures of his deceased father, working class hero and unassailable symbol of resistance against the forces of the imperialist class-enemy, the capitalists’ never-ending attempts to make inroads into Eastern Europe, Karl and, Mamochka full of zeal for the socialist ideas, and the rich aroma of homemade cookies he smelled rather than ate. Looking back he realises that he felt guilty then, guilty when his mum cried for no reason at all; guilty enough to take a huge bite and smile at her, pretend he cherished the taste, just don’t cry anymore, please.

He now opens the tin and takes out a cookie.

‘Comrade Mother, tovarich Mamochka…’ he says.

He takes a bite and falls asleep soon after he starts to chew.

*

When he wakes up he is in bed, the tin stored away, and he notices the chemical taste on his tongue.

So that’s it. Drugged again. It’s the cookies.

He gets out of bed, slowly, feels his head spinning and forgets why he got up.

Water. To drink water and flush down the foul taste.

When he opens the door to the fridge it is as full of food as it was on the first day. Somebody is watching out for him. But he is not about to find out who, not for a while.

Chapter Two

Darkness descended on the land early at this time of the year. Outside the snow fell silently and abundantly. Welcome to hell on earth, Albert thought. The air was full of Christmas carols being bludgeoned by tone-deaf, impatient children blowing saliva-soaked breath into cheap recorders, going over the first few bars of ‘Silent Night’ or ‘O Tannenbaum’ endlessly like broken records, though certainly not those in his carefully curated collection. For the little ones Christmas couldn’t come fast enough.

Albert prayed it would never come again.

That morning, the last Sunday of Advent before Christmas, his identical twin Tobias brought breakfast to Albert’s room, a cup of steaming hot, milky tea, two slices of bread with quark and marmalade and a glass of orange juice. He stuck around to make sure that Albert ate it all, hoping against hope to see his brother’s winning smile, or at least a glimpse of it.

Three long years had passed since the accident, three years full of dread and death and desperation, three years that felt like three hundred to Albert; he, who hardly ventured out into the world anymore, not even into the small, contained realm that had been his life before the accident; he, who had walked like a king among his subjects.

After the accident life had gone to pieces and so had Albert. Thank God Tobias had kept things together as far as the house and the company were concerned. Yes, Tobi had really come through, pulled more than his weight, had taken over the day-to-day running of the factory much more smoothly than expected. Three or four days a week he got into Albert’s wheelchair and clothes and let the chauffeur drive him to the office where nobody even suspected that it was Tobi giving the orders, not Albert.

Thanks to a nosy nurse who had since been fired, everybody in Eschershausen knew that Albert could actually walk again, had full control of his legs and simply chose not to use them. It didn’t matter. Where was there to go? The graveyard was just next door, and all other places of any interest — the past, mostly — were in his head. Legs were optional.

Albert knew that the next two weeks would be the worst of the year. Everything reminded him of the time just before the accident, of everything he had lost. Because of the accident his heart would break all over again, day after day, year after year. He didn’t think he could get through this season once again, God willing or not. If his life before the accident had been less perfect, more like Tobias’ life, say, maybe he would be better prepared to cope now. As it was, he was too weak, too spoilt to deal with the loss and the sense of guilt he carried. He simply wasn’t conditioned for these emotions. Not even the faith that he had finally embraced seemed to help much.

Growing up in the Federal State of Lower Saxony on the Ith, the nearby mountain range, had been a safe, idyllic experience. According to legend the Pied Piper of Hamelin had once lured a bunch of children away from their homes and brought them to the Ith, but that was but an ancient myth. In Albert’s experience this place was one of the cosiest in the world.

In Eschershausen the Catholics made up about a third of the population, a tightly knit, highly observant micro community who adhered to their laws with an almost Protestant zeal. There was room for everybody as long as you were Roman-Catholic, not divorced, obviously, and a regular churchgoer. People knew each other by name and reputation, the families getting together multiple times a year. Easter, First Communion, Confirmation, camping in summer – altar boys only – and barbecues when the weather allowed it; Corpus Christi was popular with the children as they were excused from classes. The Hoffmanns were not exactly great Catholics, but they went through the motions with sufficient regularity to be considered part of the flock.

The twin’s mother died giving birth to Tobias who was born minutes after Albert, but their father Gerhardt had done a grand job bringing them up by himself. He had taken part-time work locally to dedicate himself fully to their care. They hadn’t been rich, of course, but they had never wanted for anything, never gone hungry or cold; Dad made sure of that. Albert even had enough pocket money to start his record collection after a chance encounter with Elvis Presley, the King of Rock’n’Roll, when Albert was a child.

Life in the small town had been charmed, everything he could have hoped for. His place in the pecking order was firmly established early on and his universal popularity was never questioned. School had been a breeze and he was spared military service. Of course the girls had always swooned over Albert. He fondly remembered his first, a beauty called Senta, who plucked his virginity like a ripe plum when he was twelve and she sixteen. After that, his ubiquitous conquests were a blur – until, of course, he settled for Cordula.

Cordula Schwaiger had been in Albert’s class from his first day in school. Unlike him, she came from a wealthy family; her father was in concrete and owned the largest company in Eschershausen. For many years Albert wouldn’t give Cordi the time of day, and in hindsight that was right and proper, the way it was supposed to be. It had given him the chance to experiment sexually at will without ever having to feel bad about it. He never betrayed Cordula.

Until then he coaxed, begged and demanded sex from practically every female around, though in most cases he didn’t have to. It came easy. In fact, it came so easy that sometimes Albert passed it on — never up — to his brother. The twins looked identical and always knew what the other was feeling. Still, they couldn’t have been more different inside if they tried. Where Albert excelled, Tobi struggled or failed outright, except when it came to impersonating his brother. This was possibly Tobias’ greatest skill. Switching identities had been their favourite pastime from the day they could walk. Their second favourite game was this:

‘I think you’re adopted,’ one of the brothers would say.

‘No, you are,’ the other one said.

‘No, you.’

‘No, you.’

They had just learned the meaning of the word ‘adopted’, not the word ‘absurd’; they played it only in the privacy of their rooms when they knew nobody could hear them, and it never occurred to Albert that deep down Tobias suspected that maybe, against all laws of logic, he was indeed adopted.

Their father was often not sure who was who, but he always assumed that his ‘good son’ had to be Albert. Some of the time he was right because to Gerhardt, being good meant smiling at the right time. Smiling on the outside, that is. Albert’s insides often looked different from what he let on. When he felt a bad mood come upon him for no reason at all it could last for days, and that’s when he encouraged his brother to take over and become him for the duration of the depression. This maintained the illusion of a perpetually good-humoured Albert.

Albert loved being himself and his self-esteem grew faster than his body. Tobias loved being Albert, more so when he got to have sex with girlfriends Albert had lost interest in. Nobody ever caught on to their charade, and they only stopped when Albert started dating Cordula after a Corpus Christi procession that she insisted they go to. He knew immediately he wasn’t going to share her with anybody, and he was reasonably sure he would never have got away with it if he tried. Cordula knew him too well, read him like a page-turner and couldn’t get enough of him. His mood swings became rare and he took their dating seriously, was a warm, attentive listener and never pushed her for sex. He would wait until it was right and proper, sanctioned by her church for which he lacked respect, and by her father, for whom he didn’t.

When he started to work in the office of his future father-in-law nobody begrudged him the preferential treatment he grew accustomed to. On the contrary, it was understood that he would become the boss when the time came. Back then he was charismatic, intelligent and hard-working, as well as effortlessly easy to like.

Before long, Cordula’s father Johan Schwaiger became gravely ill, a consequence of his lifelong exposure to asbestos. He was dying to hold his grandson – figuratively at first. Soon he followed through literally, and Albert agreed to marry Cordula a year earlier than planned. The wedding was a grand affair.

Nine months later Markus came into the world, as healthy and lively as boys will, while his maternal grandfather was barely hanging on. Johan’s wife Liselotte was torn between the happiness of grand-maternity and the grief over Johan. She remained of this earth only a year longer than her spouse. She had always been a frail woman, forever marked by her ghastly experiences on the run in 1945. Her family stemmed from Silesia, a former part of the country in the east that was seceded to Poland after the war in reparation for damages inflicted. The Russian soldier who chased them off their property had taken a liking to her that Liselotte never reciprocated. The baby she carried arrived stillborn eight months later and nearly killed her in the process. When she settled in Eschershausen with her Auntie Annie, she was a broken woman.

In 1972 Cordula inherited the factory and the family fortune jointly with her (by then bed-ridden) great-aunt Annie. Initially nobody rocked the corporate boat, but board members knew a reshuffle was imminent and necessary and with Albert now at the helm, trust was not an issue.

Yes, for the first twenty-nine years of his life Albert had been happy to an unreasonable degree. Now his existence was inconsequential, a two-dimensional shadow play. On days when he bothered to shave he hardly recognised the reflection glaring back at him in the looking glass. Even his famous smile failed to dazzle now, least of all himself. Not a single day went by that he didn’t recall the former domestic soundscape, a delight he used to take for granted – Cordula’s uninhibited laugh, Markus’ tiny feet running over the parquet. His grief was so deep that he wondered why it didn’t finish him off like it had Liselotte, Cordula’s mother. Surely it was at least at strong as hers.

Increasingly he wished it would.

He knew thoughts like that were sinful and unchristian, but of late he had stopped caring. Purgatory couldn’t be worse than what he was going through now, day in, day out. The accident hadn’t paralysed him physically but it had crippled him emotionally.

Why me? Why did I survive when they didn’t?

*

It happened in 1978, a few days after the Christmas celebration that was supposed to be Markus’ best ever. They overshot their own expectations by miles. On the evening of December the twenty-third, Albert brought home a two-metre-plus pine tree and locked the living room door from the inside. On the morning of Christmas Eve he played records of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio and Silesian choirs singing Christmas songs sandwiched between tracks of solemn voices reading from the nativity story — Matthew or Luke — like his father had done when they were kids. Also like his old man he considered American crooner-carols by Bing Crosby, Dean Martin et al to be cheesy and crass. They were competent singers of jazzy pop tunes, but they made everything sound banal, casual, commercial – anything but truly festive.

Markus was busy baking cookies with his mother in the kitchen when he wasn’t trying to sneak a peek at the tree his father was busy decorating, lovingly placing strips of tinsel, blade by individual blade, one by one until it would look just right. Lunch was Silesian veal sausages with sweet gingerbread sauce followed by a digestive winter walk to collect moss for the wooden, hand-carved nativity scene. The combined scents of the baking, the freshly cut tree and the humid moss contributed immensely to the season’s atmosphere.

After coffee they put Markus to bed for a nap. The evening would be long, though the boy was too excited to get much rest beforehand. Later Tobi arrived for dinner with Dad in tow. Auntie Annie was collected from the local old people’s home though the roasted duck was too fatty for her delicate stomach and she left her plate mostly untouched. Everybody wore Sunday clothes, sang carols and read the nativity story from the bible.

Markus said, ‘Why doesn’t Santa come to our house?’

Cordula turned up her eyes. She had explained this many times but she knew he wouldn’t let it rest unless Albert said the words himself.

‘Because Santa doesn’t exist,’ he said.

‘But where do all the presents come from?’ Markus said.

By now they had reconvened to the living room where the glorious smell of fresh fir and real wax candles made the house glow with the spirit of a classic German Christmas.

‘I’ll answer that one, if you don’t mind,’ Tobi said. He was tempted to make a joke but held back as he was all too aware that Christmas was not a time for pranks in his brother’s house. ‘We’re celebrating the birth of Jesus and we’re so happy he was born and that he loved us that we buy presents for each other. The man with the red costume and white beard that you saw on 6 December…’

‘…was Saint Nicklaus. I know, Uncle Tobi, I know. What do you think I am, a baby?’ Markus said.

At midnight they went to midnight mass. It was Markus’ first year, the first time he insisted on going so they woke him after he had nodded off at half past ten. After mass came, at last, the exchange of presents. Albert could never get enough of the memory of the glow in his boy’s eyes when he opened the wrapped boxes. His own eyes matched his son’s when Cordula whispered in his ear what she had known for almost a week, but kept secret until that moment. Next year they’d have another mouth to feed. She was pregnant again.

Presently Albert made a huge effort to stem the flow of memories because between Christmas of ’78 and the accident he remembered little else.

Soon the bliss would turn to horror.

(make time stop then, in 1978, or let me remember something else, anything else)

It was hopeless. The maelstrom of memories would soon drag him under. He might read the newspaper for a while, ponder the suffering of the truly less fortunate from the poor, godforsaken countries of the world. Feeling sorry for them used to help take his mind off his own misery, but never for very long.

‘Any plans for today?’ Tobi said. Albert had forgotten he was even in the room. Of course there were never any plans.

‘I’m only asking because I have an idea, something I’m sure will cheer you up in more ways than one,’ he said.

‘I appreciate this. Really, I do. What you do for me…’ Albert said.

‘Well, okay, never mind. Maybe tomorrow. Something else, though,’ Tobias said and opened the shoebox he had been carrying under the breakfast tray.

Until now Albert hadn’t noticed it.

‘I was going through some old stuff and I found this,’ Tobi said and opened the box carefully. Inside, packed in rough paper and saw dust to protect them from scratches, were the wooden, hand-carved figures from the old nativity crib, Mary with Baby Jesus in a manger, Joseph, the donkey and the cow, shepherds, sheep and the Three Wise Men. Some relative, probably Auntie Annie, had brought this back from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land years ago. Albert knew it had been part of Cordula’s life for as long as she could remember. But, like the rest of the seasonal decorations, it hadn’t come out of the box since the accident.

A sad smile lit up Albert’s features. It lasted only a moment, was gone before it had spread to the farthest reaches of his soul, but it reminded Tobias of his brother’s charm, of why he was so well-liked. The smile, even brief, still had the power to enchant the beholder’s socks off. When it slipped away it left Albert’s face bereft, more desperate in comparison than if he hadn’t smiled at all.

‘It’s probably a bad idea. I was just thinking, since we don’t use these anymore, we would donate… No. Okay, I understand. Forget I asked. Can I get you anything else, maybe the paper?’ Tobias said, and left the room as fast as possible.

Albert was briefly furious. How could Tobi not know? Albert would never part with that crib or with anything else that reminded him of his family.

The anger passed as quickly as it had flared up. He was left alone with his thoughts, and the memories streamed through his headspace. It was 1978 again, December 28.

The cursed day.

The snow that had fallen furtively on Christmas Eve didn’t linger beyond the morning of Christmas Day. The next three days brought warmer temperatures, unusually mild ones for the time of the year.

Activities in the factory over the holidays were scaled back to an absolute minimum. After all, who was likely to buy concrete at this time of the year? It was a time to spend with loved ones, even if they outstayed their welcome as Tobias and Gerhardt were doing, at least according to Cordula.

‘I know you can’t send them packing yet, but how about we get away, at least for the day? Just the three of us on a festive shopping spree in our capital city. You know we’ve earned it.’

Hannover, Lower Saxony’s capital, was little over one hour’s drive away but they rarely ventured there. After all, it wasn’t a particularly exciting town and all their shopping needs could be met within a third of the distance, in Holzminden. A family trip to Hannover had seemed like a good idea at the time. A visit to some toy shops for Markus — not that he didn’t have enough new toys already, but never mind, let’s spoil him while he is still without siblings, a bit of fashion for Cordula — her pregnancy garments from five years ago were now passé, a nice restaurant, maybe a movie…

Obviously Tobias would want to go too when he found out. Obviously Cordula would object and obviously Albert would have to break the news to his brother.

On the morning of that day, Thursday December 28, when Albert walked into the kitchen, he found Tobias making coffee. Markus was sneaking an Elisen gingerbread into his mouth and hoping his father wouldn’t tell him off for eating biscuits before breakfast. It was five minutes past eight, but the battery of the kitchen clock had run flat. Nobody noticed.

‘And how are you on this wonderful morning? The weather is fair but the man on the radio says to hang tight, there may be a cold front on the way from the icy north. The coffee is percolating, the eggs are boiled hard but the yolk is runny and the bread rolls I picked up fresh this morning,’ Tobi said, his high spirits almost infectious.

‘About today, Tobi,’ Albert said and kissed Markus on the forehead.

‘Ah, don’t worry about today, brother. I have it all mapped out. We’re going to give poor, hard-working Cordula the day off. Then we, the three musketeers of the Hüschebr ink, go out to have a manly adventure. We drop off the old man, Gramps, at home on the Ith and go take a hike to the old red caves. Remember, Bert, how we used to play there as kids? We might find bone shrapnel or arrowheads there, from the cannibals of old,’ he said in a playfully menacing voice for the benefit of his nephew.

‘What is ‘cannibals’?’ Markus said.

Albert shook his head at Tobi, meaning ‘don’t tell him’.

‘You know what Neanderthals are, don’t you?’

Markus nodded. ‘Cavemen that look like Lars’ grandfather.’ Lars was Markus’ best friend.

Tobi sensed something bad was coming before Albert started to speak.

‘I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news but we have made different plans for today. The caves are still going to be there tomorrow or the day after that,’ Albert said.

‘Yeah? So what are we doing instead?’ Tobi said, though he knew better.

‘Yeah, Dad, where are we going?’ Markus said.

Albert lifted his son into his arms and turned away from his brother.

‘How about Mum and me are taking you to Hannover in the car, how about that?’

‘You mean without Uncle Tobi?’ Markus said, and Albert nodded.

‘Ah. Hannover, Germany’s number one city when it comes to ‘boring’,’ Tobi said.

‘Why isn’t Uncle Tobi coming?’ Markus said.

‘You heard him. He thinks Hannover is boring,’ Albert said to Markus. ‘There’re some toy shops you’ve never seen and we’re going to take you to McDonald’s or Wiener Wald, whichever you prefer, and then to the cinema or a puppet play.’

‘What’s Mad Donald or Wiener Wald?’ Markus said.

‘I’ll be right back,’ Tobias said.

Albert knew he was going to try and convince Cordula to change their plans for the day. He also knew that it would be in vain. His wife’s heart was set.

‘Don’t piss her off,’ Albert said, knowing that most likely Cordula’s mood would be affected the whole day.

Tobi gave him a look that showed how hurt he was by the fact that he was excluded from today’s plans. Albert knew he could do nothing about it. Wasn’t it high time that his brother started his own family? Of course, Dad needed looking after, more so by the day, and he wouldn’t hear of moving into an old-persons’ home. Tobi couldn’t be expected to spend all his time caring for the old man. He was understandably jealous when he was explicitly unwanted by Cordula who also had the right to want to spend a day alone with her husband and child. Something had to give, but Albert didn’t know what that something was.

Anticipating a shouting match between his wife and his brother, Albert busied himself and his son with the setting of the breakfast table in the salon.

*

Tobias reached the upstairs floor and saw that the door to Cordula’s and Albert’s bedroom was wide open. He had never done this before, not with her, but just couldn’t resist the temptation. The timing seemed right. She wasn’t looking in his direction – it was now or never.

When he entered the bedroom Cordula stood in front of a big, oval shaped mirror and applied makeup to her face. Tobias shifted his weight, his centre of gravity, by mere inches. His head moved forward. The changes were minute, all but imperceptible to a casual onlooker. If asked, Tobi himself couldn’t explain how he did it, but it worked every time. It always had. His voice became a tiny nudge deeper, his words came out a little less clipped, and the smile, Albert’s killer smile, hushed over his features. His impersonation of his twin brother was perfect to every beholder, even to their father.

Would Cordula fall for it?