Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

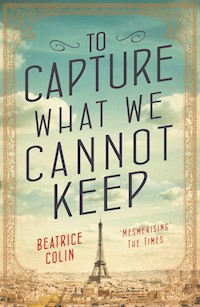

Based on one of the two engineers working for Gustave Eiffel to design the tower for the World Fair of 1889. In February 1887, Caitriona Wallace and Émile Nouguier meet in a hot air balloon, floating high above Paris - a moment of pure possibility. But back on firm ground, their vastly different social strata become clear. Cait is a widow who because of her precarious financial situation is forced to chaperone two wealthy Scottish charges. Émile is expected to take on the bourgeois stability of his family's business and choose a suitable wife. As the Eiffel Tower rises, a marvel of steel and air and light, the subject of extreme controversy and a symbol of the future, Cait and Émile must decide what their love is worth. Seamlessly weaving historical detail and vivid invention, Beatrice Colin evokes the revolutionary time in which Cait and Émile live - one of corsets and secret trysts, duels and Bohemian independence, strict tradition and Impressionist experimentation. To Capture What We Cannot Keep, stylish, provocative and shimmering, raises probing questions about a woman's place in that world, the overarching reach of class distinctions and the sacrifices love requires of us all. Winter in 19th-century Paris is wonderfully evoked and Beatrice Colin's prose is suitably mesmerising for this rather beautiful love story. - The Times

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 474

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘To be in Paris to witness the construction of the Eiffel Tower is a magnificent occasion: to have a hand, however small, in its building, even better . . . This exquisitely written, shadowy historical novel will appeal to a wide variety of readers, including fans of the Belle Époque.’

––Library Journal (starred review)

‘Once I entered the world of Beatrice Colin’s novel, To Capture What We Cannot Keep, I did not want to leave it! Set against the enticing backdrop of Parisian life in 1880s, as Monsieur Eiffel constructs his tower, this book is both daring in its historical scope and rich in its intimacy. It is a must-read for every fan of Paris, for every fan of the fight for love against the odds and for every fan of great and deeply satisfying storytelling.’

––David Gillham, The New York Times bestselling author of City of Women

‘To Capture What We Cannot Keep is reminiscent of the Paris it so beautifully, hauntingly brings to life: it’s romantic, moving and memorable. And while Beatrice Colin captures the excitement that surrounded the construction of the Eiffel Tower, the real lights of Paris are the women and men she created whose stories I avidly followed.’

––Chris Bohjalian, The New York Times bestselling author of The Guest Room and The Light in the Ruins

‘A compelling story of love constricted by the demands of separate social classes. Told against the splendidly absorbing background of the building of the Eiffel Tower, it emerges as fresh and different. A captivating read.’

––Kate Alcott, The New York Times bestselling author of The Dressmaker

Also by Beatrice Colin

The Songwriter

The Glimmer Palace

Disappearing Act

Nude Untitled

______________________

About the Author

Beatrice Colin’s most recent novel is To Capture What We Cannot Keep. She also wrote The Luminous Life of Lilly Aphrodite (published as The Glimmer Palace in the US) and The Songwriter. She has been shortlisted for a British Book Award, a Saltire Award and a Scottish Arts Council Book of the Year Award and writes short stories, screen and radio plays and for children.

Beatrice Colin is a Lecturer in Creative Writing at Strathclyde University in Glasgow.

First published in Great Britain by Allen & Unwin in 2017

First published in the United States in 2016 by Flatiron Books

Copyright © Beatrice Colin 2016

The moral right of Beatrice Colin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26-27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone:020 7269 1610

Email:[email protected]

Web:www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 76029 172 3

E-book ISBN 978 1 95253 378 5

To Paul, with love

Contents

Part I

1: February 1886

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Part II

10: June 1887

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30: September 1888

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43: February 1889

44

45

46

47

48

49

Epilogue: Edinburgh, 1890

Acknowledgments

Reading Group Guide

Before they meet at such an impressive height, the uprights appear to spring out of the ground, molded in a way by the action of the wind itself.

—GUSTAVE EIFFEL, 1885

I

____

1

____

February 1886

THE SAND ON THE Champ de Mars was powdered with snow. A huge blue- and-white-striped hot-air balloon swooned on its ropes in front of the École Militaire, the gondola tethered to a small wooden platform strung out with grubby yellow bunting. Three figures, two women and a man, hurried from a hired landau on the avenue de Suffren across the parade ground toward the balloon.

“Attendez,” called out Caitriona Wallace. “Nous arrivons!”

As she paused on the steps to wait for the other two, Cait’s vision spun with tiny points of light in a darkening fog. She had laced tight that morning, pulling until the eyeholes in her corset almost met, and now her chest rose and fell in shallow gasps as she tried to catch her breath—in, out, in and out.

“We made it,” said Jamie Arrol as he reached her. “That was a close thing.”

“Here are the tickets,” she told him. “You get on board. Your sister is just coming.”

In the wicker gondola twenty people waited impatiently, the men in bell-curve beaver hats, and the women—there were only two—in fur-lined traveling coats. But the balloon attraction wasn’t full, not on a cold winter morning with a sky so leaden it looked as if it might descend any moment, not at eleven o’clock in the morning on a Monday.

The ropes strained in the wind that blew up from the Seine, a wind that whipped the sand and the snow into a milky haze. The showground smelled of new rope and hot tar, of smoke blown from the charcoal brazier of the balloon, and underneath it all a note of something alcoholic. A flask, Cait thought, was being passed among the male passengers above. She could do with a little sip of something herself. Once on board, however, all would be well. She would not let herself imagine anything untoward, she would not visualize the gondola rising upward until it burst into flames or hurtling down until it smashed into pieces on the ground or floating away over the rooftops like Gambetta in 1871. No, she wouldn’t let her fear get the better of her. She had read the promotional leaflet thoroughly. They would be tethered to the platform by a long chain. It was quite safe. And when they had made their ascent and reached a height of three hundred meters, she would look out and see the whole world clearly.

“Come on!” she cried out to her charge. “They’re all waiting!”

As Alice Arrol finally approached the steps, her pace became little more than leisurely. A small group of Parisian ladies were standing at the base of the platform, their parasols raised to stop the wind blowing their hats away. After throwing the ladies a glance, Alice’s face stiffened into an expression that suggested nonchalance.

“Actually,” she said as she adjusted her gloves and stared up into the overcast sky, “I think I’ll stay here.”

Not five minutes earlier Alice had been almost ecstatic with excitement. Cait found it hard to hide her dismay.

“Are you sure? Wasn’t the balloon excursion your idea?”

Alice’s eyes widened in warning and her mouth curled into a small smile.

“Don’t be ridiculous.” She laughed. “I wouldn’t dream of setting foot in such an undignified contraption!”

Alice’s cheeks were flushed and her ringlets had turned into a golden frizz around her face. She had kept her hair color, the blond not turning dark. It made her look younger than she really was; her skin, nursery-pink and chalk-white with a touch of blue around the eyes. She was nineteen but often taken for much younger. Cait felt a rush of affection toward her. She still wore her newly acquired adulthood badly, like an oversize coat that she hoped to grow into.

The balloon operators started to untie the ropes. Cait glanced up at the lip of the basket. There was no sign of Jamie. She would have to tell him of the change of plan. She turned back to Alice.

“Will you wait here?”

“Are you going to go without me?” Alice asked.

At that point, the idea hadn’t even occurred to Cait. Of course she should stay behind; she was a companion, paid to accompany and supervise Alice and her brother, Jamie Arrol. Also, at thirty-one, she was far too old to be spontaneous. Worst of all, heights, steep ascents, and theater seats in the upper circle all terrified her. And yet, as she had told herself in the carriage on the drive to the showground, she would get the chance only once in her lifetime and so she must take advantage.

“Maybe I should,” she said. “Would you mind?”

“No, don’t remain on my account.”

“And you’d be safe? You wouldn’t move an inch from this spot.”

“I won’t be seduced, I promise. Just go, Mrs. Wallace.”

“The tickets are already paid for,” Cait called as she climbed toward the outstretched hand of the balloon handler. “It would be a terrible waste if we didn’t use them. Your uncle would be outraged! Mortified! Can you imagine?”

She looked back just as Alice laughed out loud, then quickly covered her mouth with her hand. Ironically, for a girl who spent so long perfecting her expressions in the mirror, she was prettiest like that, when she forgot herself.

When the last few sandbags had been tossed over the side and the ropes coiled, the pilot leaned on a lever, air rushed into the brazier, the fire roared, and the balloon began to rise with the upward momentum of an air bubble through water. Cait shut her eyes and held tight to the wicker edge of the basket as the balloon ascended. Despite everything, it was just glorious.

Eight years earlier Cait had had no idea that she would end up here, rising into the sky above Paris, practically weightless, impossibly high. She had been married, settled, grounded. Her husband, Saul Wallace, was handsome and debonair, their home in Glasgow was large and comfortable; their shared future stretched out in front of them like the red roll of a carpet. There would be children, holidays, anniversaries.

Saul was just thirty-two when his train left one side of the River Tay and failed to reach the other. It was three days after Christmas, December 1879. As Cait sat beside the fire and opened a novel, she had not known—how could she—that at that moment their life together was ending, that the Tay Bridge had collapsed and Saul Angus Wallace was drowning in black-water currents beneath several tons of hissing iron.

The hot-air balloon had reached the end of its chain and came to a sudden, jolting halt. She opened her eyes. The brazier roared, the balloon still floated in the air, the world was as she had left it; Paris below and the sky above. For a moment she focused on breathing. She wouldn’t let herself think about the empty space beneath the gondola. She wouldn’t imagine the altitude they had reached. The other passengers rushed from one side to the other, clearly unconcerned that they were suspended by nothing more than hot air. No one else was fearful, no one else stood, as she did, several feet from the basket’s rim in the grip of a private terror.

“What a view!” Jamie Arrol was peering over the edge, almost hysterical with happiness. “Come and look.”

“I will,” she said. “In a minute.”

He turned and noticed that she was alone.

“Miss Arrol changed her mind,” Cait explained.

“She missed out.” He shrugged. “There’s the Panthéon . . . the Arc de Triomphe . . . and over there . . . I think that must be Notre-Dame! Look!”

Cait steeled her resolve, then cautiously, tentatively, hesitantly peered over the edge. And there, far below, were Baron Haussmann’s wide boulevards that followed the line of the old walls of the city, the green blot of the Bois de Boulogne, the pump of black smoke from the factories in the south, the star spokes radiating from the Place de l’Étoile, and, closer, the Place du Trocadéro. And there were lines of carriages as tiny as black beetles, people as minute as ants, the city as small and regular as a set of children’s stone building blocks placed on a painted sheet.

“Well?” said Jamie.

The image blurred, her head began to pound; it was too much. She stepped back.

“You’re shaking!” Jamie laughed. “Wait until I tell my sister.”

“I’m fine,” she told him. “At least, I’ll be fine in a minute. Go, go and make the most of it.”

Despite the heat from the brazier, the air was far colder up here than on the showground. Her hands were indeed trembling, but it wasn’t just the chill. What scared her most was not the thought that she might fall out of the gondola, but the sense that she might be seized at any moment by an overwhelming compulsion to jump. Since her husband’s death she had often felt this panic, as if she existed in a liminal space, half in and half out of the world.

In the quiver of the heat coming from the fire, she tried to focus on something, anything. She heard a small click and turned. A man was standing behind a small wooden box on the other side of the basket, his face absorbed in thought. He wore a softly knotted bow tie and, unlike the rest of the passengers, wasn’t wearing a hat. As if he felt her gaze, he blinked and looked around. For no more than a fraction of a second, their eyes met. Cait’s heart accelerated, a rapid knocking against a solid wall of whalebone and wool. She swallowed and glanced away. What on earth did she think she was doing? What kind of a lady returned a man’s gaze? She turned and sought other, safer distractions. Next to her a party of Americans were discussing restaurants.

“Five francs for an apple on a plate,” one of the men was saying. “It was daylight robbery.”

“But the wine was very reasonable,” his companion pointed out.

“That may well be, but they saw me coming. I aim to avoid dining at our hotel for the remainder of my trip. The French have a nose for gullibility, so I hear.”

She was suddenly aware that the man without the hat had come to her side of the balloon and was looking out across the river toward the north of the city. She concentrated wholeheartedly on listening to the Americans’ accounts of terrible food and horrendous hotel experiences. But she was conscious of him, of his proximity, of the wooden box he was carrying, of his hair swept back from his forehead falling in loose, dark curls over his collar, of the rise of his frozen breath mingling with her own.

“Fleas!” one voice rang out. “Fleas everywhere!”

“I had bedbugs,” another agreed. “They even got into my toothbrush.”

The man took another, smaller wooden box out of the first box and carefully attached it to three metal legs. It looked like some sort of photographic device. Photography was the new craze in Paris, and she had seen dozens of men carrying those mahogany and brass boxes, strolling up and down the Quais or setting up in the Luxembourg Gardens.

She could see now that he was slightly older than he had first appeared, maybe around forty. His dark hair was flecked with gray, his coat was finely cut and his shoes polished; he looked cared for. And yet there was something in the way he moved, in the slant of his shoulders and the way he took up space in the world that she recognized. He was a man who was, or had been, lonely.

As she watched, he opened the box and extended a small concertina shape from the front. And then he stepped to the side of the gondola and leaned over. Cait felt a surge, the momentum of falling, headlong, into nothingness. Of its own accord, her hand reached out and grabbed his arm. He turned.

“Madame?” he said.

“Excuse me,” she blurted out in French. “But you looked as if you were about to—”

Cait opened her mouth but couldn’t say the word.

“Throw myself over the edge?” he asked in French.

She blinked at him.

“I was going to say ‘fall.’ ”

“Not today, but thank you for your concern,” he said.

He glanced down to where her hand still gripped his sleeve. It was her left hand, bare now of the wedding band she used to wear.

“I’m so sorry,” she said as she let him go.

“Not at all. Are you all right?”

“I have a fear of heights,” she explained.

How ridiculous that must sound, she thought suddenly, how lame, how patently untrue, in a hot-air balloon of all places. His eyes, however, were on her face, his gaze unwavering. He wasn’t laughing.

“I spend a lot of time in the air,” he said.

“Really? What are you, an aerialist?”

He laughed and his face lifted. It was not, she decided, an unpleasant face.

“Close,” he said. “Are you enjoying it?”

“It certainly is an experience,” she replied. “I’ve never been in a hot-air balloon before. I’m not sure I would again.”

“I rather like it. The sensation that one is attached to the Earth only by a chain. And now, if you will excuse me for one moment, I must take another picture.”

He moved his camera toward the edge, looked through a tiny hole in the back, and adjusted the concertina in front. Once he was satisfied, he turned a dial, reached into his case, found a flat black box, and attached it to the camera’s back.

“You’re English?” he said as he pulled a thin metal plate from inside the box.

“Scottish,” she replied.

He smiled, then consulted his pocket watch.

“I’m exposing the plate,” he explained. “It must be kept very still for twenty seconds exactly.”

She held her breath as he counted out the seconds.

“Voilà!” he said as he wound the shutter closed again. “Just in time.”

She looked up and noticed that a thin mist had begun to descend, enveloping the balloon in white.

“We’ll have to imagine the view instead,” she suggested.

He turned and gave her his full attention again.

“Then imagine a tower,” he said. “The tallest tower in the world. It will be built right here on the Champ de Mars for the World’s Fair, to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution. You won’t have to come up in a balloon anymore.”

“That!” she said. “But everyone says it’s going to be awful, just a glorified pylon.”

He laughed and began to put away his camera.

“Or a truly tragic lamppost,” he said.

There was a sudden tug and the balloon dropped a couple of feet. The passengers let out a cry of alarm, followed quickly by a show of amusement. Maybe they weren’t all quite as fearless as they appeared.

“That was short,” said Jamie, appearing suddenly at her elbow. “And you can’t see anything now. Not sure it was worth the price of the ticket.”

“You should take the steamboat, a bateau-mouche,” the Frenchman suggested. “The route from Charenton to Auteuil is the best and only costs twenty centimes. It takes you through the whole city by the river.”

The two men began to chat, as men do, about professions and prospects. Cait felt a spike of disappointment; she wished that Jamie hadn’t come looking for her.

“You’re an engineer,” said Jamie. “What a coincidence! You might have heard of my uncle, William Arrol. Our company is working on the Forth Bridge near Edinburgh. And we’ve almost finished one across the Tay, to replace the one that collapsed.”

He glanced briefly in Cait’s direction. The balloon was yanked down another couple of feet. Something within her plummeted in tandem. She had forgotten herself. She was thirty-one years old; she’d had her chance.

“What are your current projects?” Jamie asked the engineer.

“A tower made of iron,” he said, and smiled at Cait.

“Not Eiffel’s tower?” said Jamie. “The one they’re going to build somewhere around here?”

“I designed it,” he replied. “Together with my colleague, Maurice Koechlin. We work for Gustave Eiffel.”

Cait covered her mouth with her hand. Beneath her fingertips her cheeks burned.

“You should have told me,” she said. “There I was, calling it a truly tragic lamppost.”

Jamie glanced at her. Clearly she had spoken out of turn. The Frenchman, however, didn’t seem offended, but amused.

“I called it that, not you. Today I was trying to take some photographs of the site for our archive,” he explained. “We start digging the foundations next week.”

“Really! And how long do you expect construction to take?” Jamie asked.

“It must be ready for the Great Exhibition, so two years at the most. And once she stands, you will be able to see her from all over the city.”

“Impressive! You know, I’m training to be an engineer myself.”

Cait was surprised to hear Jamie say it. His uncle had paid for school, for university, and when he had dropped out, he had given him an apprenticeship in his company. A directorship was promised, but first Jamie would have to prove himself, working his way up, like his uncle had, from the shop floor. He had learned the basics of civil engineering by drawing endless plans and drilling rivet holes, but he had not shone, coming in late and going home after lunch. After several strained conversations with his uncle, it was agreed that he would take a sabbatical to think things over. While traveling for the last six months around Europe, he had considered careers such as wine merchant or chocolate importer.

“I’m afraid I didn’t catch your name?” Jamie asked.

“Émile Nouguier,” the Frenchman replied.

“So if you designed it, why isn’t the tower named after you?” Cait asked.

“Eiffel bought the patent from us,” he replied. “And now as well as building it, he is paying for most of it.”

“I heard it was going to cost him millions of francs,” said Jamie. “Is that true?”

“It is. Although he hopes he will recoup most of it through ticket sales.”

The gondola landed with a thump on the sand of the parade ground. The American passengers gave a spontaneous round of applause.

“It’s been a pleasure, Monsieur Nouguier,” Jamie said. “Is your wife on board?”

“Alas, there is no one that fits that description.”

“We’re in the same boat, then,” Jamie said. “You must meet my sister.”

Émile Nouguier bowed in Cait’s direction.

“No, I’m just a family friend,” she said. “Caitriona Wallace.”

“Forgive me,” he said softly in French. “Caitriona.”

A small jolt raced through her. He had addressed her by her first name. It was better, she decided, to ignore it. It was better to appear oblivious to his overfamiliarity.

“Well,” she said, “good luck with your tower.”

“Thank you,” he replied.

Almost all the passengers had disembarked. The crew were coiling ropes and piling sandbags. Water was thrown over the basket of hot coals.

“Mrs. Wallace!” said Jamie, standing on the platform steps, waiting to help her down. “Can’t wait all day!”

Alice was standing at the bottom, her face doll-blank. The ladies with the parasols had gone.

“How was it?” she asked.

“You should have come,” Cait replied.

“There’s someone I want you to meet,” Jamie called out from behind.

Alice looked at Cait in horror. Who on earth, her face seemed to say, could be worth meeting on a hot-air balloon attraction?

“May I present my sister,” Jamie said once the engineer had reached the bottom of the steps, “Miss Alice Arrol. This is Monsieur Nouguier, the highly esteemed engineer.”

Jamie was hardly subtle; the young unmarried sister, the blatant advertising of her availability, the implication that Nouguier might be of the right social standing to take an interest. But if the engineer was aware of any of this, his face didn’t reveal it.

“Mademoiselle,” he said with a small bow.

“Enchantée,” Alice replied.

There was a small, expectant silence.

“How long are you staying in Paris?” he asked Jamie.

“Just until the weekend. We’re on a Grand Tour, of sorts. After meandering through the Low Countries, we spent too long in Rome. We had to miss Venice entirely. But our stay in Paris has been thoroughly worthwhile now we’ve met you.”

Cait was painfully aware, as she had been many times in Paris, of their poor mastery of social etiquette, of how clear it was that they had come from a less sophisticated place. Their manners were parochial, so parochial that they didn’t even realize it.

“If you have time before you leave, I would be happy to receive your call.” Nouguier handed Jamie his card. “As an engineer you might be interested in seeing the workshop in Levallois-Perret.”

“I would indeed,” said Jamie. “Thank you.”

Once Émile had taken his leave, Alice rolled her eyes.

“Please,” she said, “don’t drag us to a workshop.”

“Do you know who that was?” Jamie whispered. “He works with Gustave Eiffel, the Gustave Eiffel. And he’s unattached!”

“Jamie!” she said. “Before you start your matchmaking, I’d like to point out that he wasn’t even wearing a hat!”

“Shh,” said her brother. “He might hear you.”

But Émile Nouguier was already halfway across the parade grounds, heading toward the Seine, his figure a dark stroke against the sand. As Cait watched, it started to snow, and within a minute he began to disappear, fading from black to gray to nothing at all.

2

____

AND ALL WAS WHITE. Émile looked up into the space where the tower would stand, into the slow swirl of snow as it gracefully descended. Ice flowers, as snowflakes were sometimes known. He caught one in his hand and watched as it melted into a drop of water. Were beautiful things more beautiful when you couldn’t keep them? The tower wouldn’t stand for long: twenty years. Compared to other structures of its size, it was a blink of the eye, a single heartbeat, an ice flower.

He pictured Gabrielle lying on his bed that morning, her dark hair undone and her clothes unlaced. How much longer would their affair continue? A week? A month? Surely not much more? He suddenly longed for simplicity, for honesty, for a lack of artifice and an open-eyed gaze like that of the woman he’d just met in the balloon. But this was Paris and nothing was simple. Relationships always came with caveats.

Gabrielle thought him lucky to have her. She moved in the kind of circles in which he was not welcome; she modeled for artists and had been intimate with most of them, or so she led him to believe, name-dropping Degas, Renoir, and Monet, and the boat parties they had thrown for her at Maison Fournaise. She made it no secret either that she was married to a lesser-known painter who didn’t mind what she did. Once she’d mentioned a daughter, a girl of about eight, whom they farmed out to grandparents.

The affair had begun three months earlier when she and Émile had hailed the same cab outside a theater on the Place du Châtelet. It was raining hard, and both had insisted the other take it until a gentleman in a top hat jumped in front and took it himself. To quell their mutual outrage, a cognac or two in the theater bar had seemed like a good idea. Later, Émile hailed another cab and this time they both climbed inside.

Of course, he knew that the relationship was unsustainable, untenable, indefensible, but it suited them both, for the moment. He gifted her with nice clothes and jewelry and she returned the favor in other ways. If he ever felt guilty, he paid a visit to her favorite shop, Boucheron, on the Place Vendôme.

“Are you coming to the opening?” Gabrielle had asked him that morning. She stood in front of a small mirror, adjusting her hat and fixing it with pins.

“Will your husband be there?” he had asked.

“He is exhibiting twelve paintings. So yes, I expect he will.”

“Then no.”

He turned, lay flat on his back, and stared up at the ceiling.

“He is still upset that he wasn’t chosen for the Impressionist show in New York,” she went on, oblivious.

“And are there any paintings of you?” he asked.

She stopped what she was doing and looked over at him.

“A few,” she replied. “Why?”

“No reason.”

He climbed out of bed and began to dress. And as he fastened his collar and buttoned his braces, he remembered the rush of his heart beneath the palm of her hand, the capitulation of his body beneath her fingertips. Possession in the beat of the blood but not in the heart. So why did the idea of her being with another man rile him?

Gabrielle was watching him in the mirror. Finally she turned.

“Émile,” she said, “you’re in a temper, aren’t you?”

“No! I must go to work, that’s all. I’m going to be late.”

“But it’s not even eight.”

She took off her hat and cast it aside. She undid his collar, she kissed his neck, his ear, his mouth; then once more she took his hands and drew him toward the bed.

“I’d like to paint you,” he had whispered after.

“But what on earth would I look like?” She laughed. “A steel girder for a face, perhaps, with two rivets for eyes?”

This was what she really thought of him; he was an engineer, not an artist. And yet there was art in his work, in the soar of a structure and the arch of a bridge, in every framework of light and air and iron.

“You might think differently of me when you see our tower,” he said.

“How can metal bolted to metal be art?” Gabrielle replied.

“Wait and see. Wait until you stand at the top and look out at the whole city below.”

“But why would I want to do that?” she insisted.

“Why wouldn’t you?” he replied. “Because you can!”

She looked at him, her chin raised and her eyes narrowed. “I’ll believe it when I see it,” she said, and rolled away from him.

His father had had several mistresses over the years. They came to the glass factory after hours, when the furnaces were cooling and the glass blowers had gone home for the day. Émile remembered them all clearly, Isabelle with the red hair; Chantelle, the wife of the baker; Miriam, who had a beautiful singing voice. His mother must have known—everyone else did—but dealt with it stoically. Cedric Nouguier was a factory owner, an important man in the small town of La Villette on the outskirts of Paris. As long as he avoided scandal, he could do what he liked.

At his age, however, Émile needed a wife, not a mistress. But what could he offer her? Although he had inherited an apartment in Paris in the fifth arrondissement, he rarely used it. He traveled for work—Portugal, America, Hungary, Russia—and lived for months on end in hotels. The tower construction would be one of his first jobs in Paris, and he sometimes wondered if he saw the city, the world, his life, like a visitor might—fleetingly, as if he were just passing through. A blink or two and it would be gone. And yet he must marry and have children soon—a rich woman, preferably, with money to invest in his family’s factory. He was reminded of these facts weekly when he visited his mother, who lived in the hope that she could one day die peacefully, safe in the knowledge that the Nouguier family with all its elderly dependents and antiquated business was still a going concern.

The snow hadn’t settled, and it melted into the cobbles as soon as it landed. Émile walked along the Seine past lines of barges heading into the city. They were moving so slowly that they left nothing more than gentle ripples on the surface. Most of their weight was below the waterline. He looked down and saw himself in the black water, reflected, fragmented, pulled apart and put back together again over and over until the water smoothed, dark as glass.

3

____

EVEN THIS FAR out of the city, the river was full of paddle steamers and river barges, light yawls and chain tugs, with great wheels heaving up dripping lengths from the riverbed. Several bateaux-mouches were tied up at the pontoon when they arrived, but only one, a stream of smoke coming from its chimney, looked ready to depart.

“Quand partez-vous?” asked Cait.

“In two minutes,” the captain replied in English.

According to a timetable pinned inside a wooden frame, it would take about an hour and a half to reach Auteuil on the other side of Paris, and a little less to return. While Jamie arranged a time with the carriage driver to pick them up, Cait looked out across the water. It was a breathless day, the winter light the color of green tea. A string of small rowing boats bobbed in the swell. A little farther down were a floating restaurant, a bathing house, and a wash house. Several women were lathering sheets in the freezing water from a wooden platform. As she watched, a shaft of sun broke through the early-morning haze.

“We could sit outside?” suggested Cait once they had bought their tickets and had them stamped.

“Too cold,” said Alice.

And so they found a bench inside the cabin next to a steamed-up window. The boat wasn’t busy; several elderly couples who sat staring straight ahead in silence, a woman with three small children, and a nun. The air was thick with the smell of mildew and tar and engine oil and, underneath it all, the faint, fetid stink of the river.

“It doesn’t look like much at all,” Alice said as she wiped the window and stared out. “Where are we again?”

“A town called Charenton,” Cait replied.

“I know that. But is there anything here apart from the river?”

Cait opened the guidebook and looked in the index.

“ ‘Situated between the Bois, the Marne, and the Seine,’ ” she read out, “ ‘a place chiefly known for its lunatic asylum.’ ”

She looked up at Alice and they both started to laugh.

“So much for the quest to find the chic,” said Jamie, “the elegant, the je ne sais quoi.”

“I told you we should have gone shopping,” said Alice.

“Give it a chance,” said Jamie. “We haven’t even left the dock yet. And I’m determined to see as much of Paris as I can in the time we have left, not just the insides of department stores or hansom cabs.”

Cait stared down at a map of Paris’s canals and rivers, blue snakes on brick red. In two days they would be heading back to Dover, crossing the Channel, and taking the train from London back to Glasgow. And she was filled with apprehension, with dread, with an almost unfathomable melancholy.

She had left her tenement flat in Glasgow in the autumn of the previous year, covering all the furniture with dust sheets and canceling all the deliveries. On the day of their departure it had been raining heavily and the gutters were filled with fallen leaves and the black swirl of city dirt. She sent her small case ahead and made her way from Pollokshields into the city on foot, following the route of the railway line. As she waited for Alice and Jamie at the station, it was only the rain and the thought of getting wetter than she already was that prevented her from walking home again. Why, she asked herself, had she accepted the role of lady’s companion, of chaperone to Alice Arrol? But she knew why; it was the type of job taken by women who have no other option.

The villa had been sold, along with the wedding silver, years earlier. After being badly advised, however, Cait’s financial investments had dwindled to almost nothing. She lived in a modest one-bedroom apartment on the second floor of a building that looked across the railway. Once she realized that her savings wouldn’t cover the bills for much longer, she had answered an advertisement in the Glasgow Herald.

“What luck,” William Arrol had said at the interview. “I have been looking for a woman of exactly your quality.”

He went on to tell her that he’d discounted a dozen women already for reasons he would not go into. But then he leaned forward and began to laugh.

“Between you and me, one of them was so old,” he said, “that she needed a companion of her own just to get up the stairs. Another, too young. She looked as if she was out to snatch any eligible man for herself. But you, you’re a mature woman. You dress well. You’re educated, refined, and you have a reliable manner. Mrs. Wallace, you’re the perfect lady’s chaperone.”

He sat back, pleased with his appraisal. Cait did her best to hide the effect of his words.

“Before I agree to anything,” she said, “I’d need to know what the job involves.”

“I’m so sorry,” said Arrol. “I’m jumping ahead of myself. You’d be a lady’s chaperone to my niece and, to a lesser extent, my nephew, for six months. They’re going on the Grand Tour, as I believe it’s known, to absorb the culture of the Continent and complete their education. I would pay all expenses and offer a generous stipend. If that sounds acceptable, then the position’s yours.”

Alice and Jamie Arrol arrived at the station fifteen minutes late, in a fluster of umbrellas and excuses, accompanied by four men carrying two huge trunks. Most of their friends had come along to see them off. As the porter installed them in their carriage, the guard gave all three a good talking-to. He wouldn’t wait, not even for the likes of them. Then, as the train finally pulled out of the station, Alice had opened the window, waved goodbye to the crowd, and cried a little.

“I’ll find her a rich husband,” Jamie called out. “A German baron or an Italian prince.”

“What you need is a wife,” someone called out. “To take you in hand.”

Even as the train began to gather speed, Cait still thought there was time to change her mind. She stared out of the window as they sped south and, just for a fraction of a second, caught a glance of her flat, its windows black and empty. It was then she realized there was absolutely nothing to go home for.

The London train was busy, but as they sat in the first-class restaurant, she was the only one who steamed gently as her clothes dried. In Dover, waiting for the boat, the sun came out. She hadn’t packed a parasol and so she let the autumn sun warm her face. Behind her were eight years of rain.

The steamboat was about to depart, the gangplank raised and ropes stowed. A carriage drew to a stop on the road and three young men and three young women clambered out. A couple of them ran down to the pontoon and begged the captain to wait for them.

“Why can’t they catch the next one?” Alice said.

“Maybe they’re trying to escape from the asylum?” Jamie whispered.

The captain waited; the boat wasn’t full. The gangplank was lowered again and the group came aboard lugging baskets and bottles, blankets and pillows. The men wore colored shirts and bright silk waistcoats under their coats. One of them carried a small wooden guitar. The women wore tea gowns in pale blue, dusty pink, and deep red velvet. One carried a bouquet of flowers.

“I don’t think they’re lunatics,” Alice whispered. “They look like artists.”

“Isn’t that the same thing?” asked Jamie.

“I think it’s a wedding party,” said Cait.

Alice peered through the window and watched as they set everything down on the benches outside. And then she sat back and looked disappointed.

“Why aren’t we sitting outside?” she said.

“Because you didn’t want to,” Jamie replied. “Remember?”

“Why did you listen to me? You never usually listen to me!”

Jamie caught Cait’s eye and sighed. His sister, his face seemed to say, was impossible.

They had been in Paris for a month, staying in a small suite in the Hôtel Meurice on the rue de Rivoli. If it had been up to their uncle, they would have found cheaper lodgings. He wouldn’t discover until later, however, when he received the bill in the post. But what would William Arrol know? Alice had insisted that they had to mix with the right sort of people, and he was clearly the wrong sort.

The son of a spinner, William Arrol had started work at nine and studied mechanics and hydraulics at night school. By the time he was thirty, he was running a successful engineering business, the Dalmarnock Iron Works. The firm had won contracts for dozens of projects, including the Bothwell Viaduct and the Caledonian Railway Bridge, and made him a small fortune. When his own wife, Elizabeth, failed to produce any heirs, he turned all his attention to his widower brother’s children, Alice and Jamie. His nephew, he hoped, would eventually take over the business, while his niece, with his financial support, would make a decent marriage. His money was new, but his values were resolutely conservative.

With the steam up, the paddles spinning, and the funnel puffing smoke, the boat moved out into the middle of the river and began to head downstream. They chugged under bridges, along the edge of open fields, and past the dripping brick walls of factories. Sometimes they stopped to let more passengers on and others off, but never for more than a few moments. As they approached the center of Paris the river’s edge became built up with warehouses. The city relied on its waterways, and the barges they passed carried everything from flowers to cattle, fresh fish to coal.

The Seine divided around the Île de la Cité, and the narrow channels became congested as they passed Notre-Dame. At the Hôtel de Ville, half a dozen barges were unloading and the air was sweet and tart with the smell of apples. On the deck one of the artists picked up his guitar and started to pluck it. The woman in red velvet, the bride, Cait guessed, laid her head in the lap of a young man with a pale beard and stared up at the stone spans of the Pont Neuf. Another man poured a bottle of red wine into six glasses and broke a baguette.

“À votre santé!” he called out to his friends, to the other passengers, to the people who peered down at them from the bridge above. “Bonne chance!”

A little farther on, they passed the Louvre in silence. Alice had refused to go inside; she had balked at the suggestion of any more Grand Masters or ancient Egyptians. Surely, she had insisted, the Uffizi in Florence had been enough art. The steamboat moved on, stopping at the Jardin des Tuileries and then, on other side, the lavish Hôtel des Invalides.

“It looks bigger from the river,” said Alice. “What’s inside it again?”

“The tomb of Napoleon,” said Jamie. “I think we should visit it.”

“Haven’t we seen plenty of dead people already?” Alice asked. “How long did we spend in Père-Lachaise Cemetery? Hours and hours.”

“Not long enough,” said Jamie. “It’s only out of consideration to you that we’re not visiting the catacombs.”

“What on earth is interesting about a pile of bones?”

“If you would take a look, maybe you’d find out,” he replied.

Jamie glared at his sister. He had become increasingly less diplomatic as the trip progressed. Alice, no matter how sweet, had never been reasonable.

At the Champ de Mars, piles of earth were heaped along the quayside. Several horses and carts were carrying away loads of rubble. A dozen men were digging with spades. The sound of hammering echoed across the water.

“What have they done?” Alice lamented.

“It’s the tower,” said Jamie. “They’ve started on the foundations.”

At the far side of the site, Cait could make out a couple of men taking notes. She wondered if one of them was Émile Nouguier.

“I’m going out,” said Alice. “For a breath of air. Alone, if you don’t mind.”

She glanced around to see if either Jamie or Cait would challenge her.

“Go on, then,” said Jamie. “Nobody’s stopping you.”

Cait suddenly felt sorry for him, stuck with two women in one of the most exciting cities in the world.

“You don’t have to stay with us all the time,” she said. “Why don’t you get off at the next stop? We could meet you for dinner at the hotel later.”

Jamie stood up, the tension in his face immediately lifting.

“Now, there’s an idea,” he said. “I would rather like to see the Titians in the Louvre before we leave. And do you think I should call on my engineering friend? He might consider me rather remiss if I don’t. Now, where’s the card he gave me?”

He pulled it out of his waistcoat pocket.

“ ‘Émile Nouguier,’ ” he read out, his accent poor.

Cait felt a flush of heat in her face as she corrected his pronunciation.

“You’ll have to send a note first,” she said. “You can’t just turn up unexpectedly.”

Jamie turned and stared at her. “You think I should just forget it, don’t you?”

The boat bobbed on the swell; they were simply passing through the city, tourists ticking off the sights one by one, nothing else. She should stop wanting more, stop craving the unattainable, especially with her history. But then again, what did it matter? They were going home in a couple of days. There was nothing at stake, nothing at risk.

“On the contrary. I’m sure Alice would like to go too,” she said. “If you arranged it.”

“Alice?” Jamie repeated with a frown. And then he smiled. “I’m sure she could feign an interest in engineering for a little while at least. Good thinking! I’ll ask him if he can receive all three of us.”

The boat was pulling in to moor at the Trocadéro.

“Go on, then,” she said. “If you’re going.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Wallace,” he said as he placed his hat back on his head. “And would you tell my sister that I’ll see her at dinner?”

“In due course. Right now I think she is somewhat occupied.”

They both looked out the window. Alice was clutching the boat’s railing. But her eyes weren’t on the view. Instead she watched, with a mixture of horror and delight, as one of the women, still with a glass of red wine in one hand, pulled up her skirts to reveal purple bloomers and danced alone on the deck.

4

____

“THAT’S GEORGES SEURAT,” Gabrielle whispered to Émile. A tall, thin man with a high forehead and pointed beard stood in the corner. “And those are his paintings.”

They were landscapes, mostly, hung from floor to ceiling among hundreds of other canvases. The one nearest was called Le Pont de Courbevoie. Émile stepped a little closer. It was made up of tiny dots of paint; what looked like purple from a distance was in fact bright red beside pale blue. Elsewhere, Seurat had used light beside dark and warm colors beside cold.

“I know where this is,” he said. “It’s the north side of the island, La Grande Jatte. Didn’t he paint the island before? What’s the work called?”

“A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte?” said Gabrielle. “You’ve seen it? Isn’t it terrible? The people look like dolls. Did you hear about what happened when he exhibited it in Brussels last month? There was an outrage!”

She was whispering; the gallery was crowded. Everyone wanted to see what the fuss was about and now they peered at Seurat’s work, some blinking rapidly, as if the bright colors and the vibrant tones were too much for their eyes.

“I doubt he’ll ever sell the thing,” Gabrielle went on. “It’s huge too. Such a waste of time!” She looked up and Seurat caught her eye. She gave him a small bow of her head.

“That’s him, you say?” said Émile.

“Please don’t speak to him. You’ll be stuck for hours while he goes on and on about science and harmony and all these theories he’s dreamed up with his friend Paul Signac, who, incidentally, is even worse.”

“Maybe I should buy it?”

Gabrielle looked genuinely shocked.

“La Grande Jatte? Have you lost your mind? It would be a criminal waste of money, money you’d never get back. Besides, what would you do with it?”

“I’d hang it in my apartment,” he said.

“But Émile! You’d never get it through the door!”

She laughed, her head tossed back to reveal her throat. It wasn’t just for his benefit. As well as the general public, the gallery was full of artists and dealers—the former in clothes of unusual colors, with large mustaches or the brown-weathered skin of a long stay somewhere hot; the latter in sober, expensive suits with pocket watches. This was the opening of the third exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. Unlike the official salon, the Société had no rigid selection policy or jury and was open to any artist as long as he or she paid a small fee. By coming to the opening of the exhibition, everyone wanted to be noticed, to be acknowledged, to be appreciated. And yet, to what end?

“Nobody’s selling anything anymore,” Gabrielle whispered a little later. “It’s not like the old days. And those hideous paintings by Seurat. I’m sure they put people off.”

The show was being held in the cavernous Pavillon de la Ville de Paris on the Champs-Élysées. Two stories high with a ceiling of glass, the Pavillon had been built for the World’s Fair in 1879. Now the colonnaded foyer was used for exhibiting sculpture while thousands of paintings had been hung in the galleries. The private view wasn’t particularly busy, and yet still hundreds of people swarmed up the stairs and along the balconies to cram into the galleries, most of them looking for artists they’d read about in the newspaper.

“Look at that,” said a young woman in English. “If I half close my eyes—”

For an instant, Émile thought the voice sounded familiar and turned. It was a girl and her elderly mother, a pair he didn’t recognize, who started when he looked at them as if he had just asked for spare change.

“Pardon,” he said in French.

That morning he’d received a letter from the young man he had met in the balloon, requesting a tour of the workshop. It wasn’t unthinkable, he told himself, that they would come to the private view. They might even be here, in another gallery, at this very moment. And he suddenly remembered the chill of the air, a hand on his sleeve, the taste of smoke on his lips.

“Who on earth gave her a ticket?” Gabrielle said.

A large woman had appeared at the door of the gallery, unaccompanied and a little out of breath. She wore a pink ruffled evening gown with a huge bustle, in a style that was long out of fashion. A velvet ribbon was tied around her neck and her ample cleavage was decorated with artificial flowers. Even in the pale light that filtered through the blinds that covered every window, it was impossible not to notice the splatter of something dark across the hem of her skirt—wine perhaps, or mud. Émile felt a pang of sympathy for her. He wondered if she’d noticed. She would most likely notice later, when it was too late, and would feel the slow seep of shame spread across her body like the stain.

“The Folies-Bergère is on the rue Richer,” someone whispered, loud enough for everyone to hear.

The woman jutted out her well-padded chin. She had no time for these people, her face seemed to say; she had other business to attend to. Her eyes ran over the crowd several times before they fell on Seurat. And then she adjusted her bodice, pulled back her shoulders, walked right over, and kissed him full on the lips. The room inhaled as one, a mass suction of indignation and barely disguised horror.

“His mistress,” Gabrielle mouthed. “Aren’t they both perfectly awful? Let’s go.”

Gabrielle took his arm and they wandered on through other rooms, rooms hung with hundreds and hundreds of paintings.

“So much mediocrity,” she said. “Everyone thinks they can be an artist now. And the thing is, they can’t.”

“And where are you?” he asked. “I’d like to see the paintings of you.”

Gabrielle turned and gazed up at him. In the half-light, her skin was pale, her bottom lip a deep, dark red.

“In the next room,” she said, her large eyes blinking with concern. “But please? Don’t—”

“Don’t?”

She didn’t reply. Instead she glanced away toward a door that opened onto the balcony above the main foyer. And then with a handful of skirt in her hand, she turned and sailed toward it. Don’t. The word echoed in his head. Don’t make a scene? Don’t fall in love with her? He wasn’t sure he could even if he wanted to.

That evening, Gabrielle wore an off-the-shoulder dress. Her hair was pulled into a swirl on the top of her head. Her shoulders were narrow, her waist even more so. Earlier, he had wanted to reach out and place both hands on those slender hips, their line drawn by thin bones of steel inside her corset, and pull her to him. As if she could feel his eyes on her, Gabrielle had turned. But instead of catching his eye, she had looked beyond. He glanced around. An elderly well-dressed gentleman with a monocle was staring in her direction. Gabrielle’s mouth was slightly open and a tiny smile had formed on her lips.

“Monsieur Nouguier,” called a voice. “Thank you for coming. My wife assured me you would.”

A man was limping toward him with his hand outstretched. Émile felt a wash of guilt; so this was Gabrielle’s husband.

“Wouldn’t miss it for the world,” Émile replied.

“Come,” the painter said, “come and see my new work. It is the best, I think, the best I have ever done.”

Gabrielle’s husband was nothing like he had imagined. Although his accent was middle-class, the painter looked unkempt, poor, ill. He smelled of raw garlic and pigskin leather, of stale wine and smoke. As Émile followed him through the crowd, he noticed that one of his legs was wasted. His collar was frayed and the heels of his boots worn down. What misfortunes had befallen the artist aside from polio? And how could he bear to share his beautiful wife with anyone?

“The light is better in this room,” the painter said. “It faces north.”

Émile purposely waited until he was right in the center of the gallery before he looked at the work. A woman reading a book; a woman gazing at herself in the mirror; a woman asleep in bed, her face turned away; a woman naked, her hair filled with flowers, her face caught in a smile.

“You like them?” the painter asked.

It wasn’t Gabrielle; the limbs were too clumsy, the line wasn’t fluid, the turn of the chin was not graceful enough. And yet, it was.

“I do,” he said. “Very much.”

Later, Émile stood at the window of the cloakroom and watched a line of carriages roll through the rain on the Champs-Élysées. A man with one arm stepped out from beneath a tree. He unbuttoned his filthy shirt and splashed water around his neck and chest. And then he rubbed his beard, his face, his body, his stump. But this was city rain, the kind of rain that left streaks of black down polished windows and smuts on clean washing. Émile suspected that the man would soon be even dirtier than he was before the rain began.

Had the man been in Paris in May 1871, he wondered, the “bloody week” when the streets of the city had been piled with the corpses of insurrectionists and the air thick with smoke as Paris burned? Was that where he had lost his arm? Émile had missed the siege, had been away working in the Austro-Hungarian Empire on a bridge over the Tisza River. He had not suffered.