Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Shortlisted for the Sisters in Crime Davitt Award for Adult Fiction How long can you hide the truth? The Kelly family has always been trouble. When a fire in a remote caravan community kills nine people, including 17-year-old Sabine Kelly's mother and sister, Sabine confesses to the murders. Shortly after, she escapes custody and disappears. Recently made redundant from marriage, motherhood and her career, journalist Rachel Weidermann has long suspected Sabine made her way back to the river — now, twelve years after the 'Caravan Murders', she has the time and the tenacity to corner a fugitive and land the story of the year. Rachel's ambition lights the fuse leading to a brutal chain of events, and the web Sabine weaves will force Rachel to question everything she believes. Vikki Wakefield's compelling psychological thriller is about class, corruption, love, loyalty, and the vindication of truth and justice. And a brave dog called Blue.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 469

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for To the River

‘Vikki Wakefield’s To the River gets under your skin. Two very different women are brought together in the search for the truth and something like justice. Covered in dog hair and splattered with river mud, this taut, muscular thriller absolutely delivers’ Hayley Scrivenor, author of Dirt Town

‘A completely gripping story, with two brave, tough and damaged women at its heart. Vikki Wakefield is a brilliant writer’ Shelley Burr, author of Wake

‘An atmospheric mystery with layer upon layer of secrets. Two flawed women discover how much they are willing to risk when justice is not equal and the system is not there to protect them’ Dinuka McKenzie, author of The Torrent

‘Heartrending and heart-pounding. At times beautiful and graceful, at times propulsive and frantic – just like a river’ Michelle Prak, author of The Rush

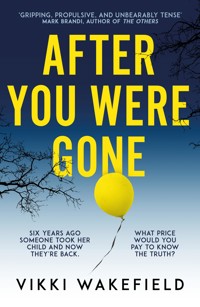

Praise for After You Were Gone

‘Elegantly written and utterly chilling. A dark and twisting novel of psychological suspense that will have you turning pages and checking your locks’ Emma Viskic, author of Those Who Perish

‘After You Were Gone is the very best kind of thriller: tender and wise as well as pulse-poundingly tense’ Anna Downes, author of The Safe Place

‘Gripping, propulsive, and unbearably tense – the best psychological thriller I’ve read in years’ Mark Brandi, author of The Others

‘An original thriller full of empathy. Flawed and vulnerable, Abbie is so real. I was with her all the way’ Sarah Bailey, author of The Housemate

‘Spooky, believable, compelling. I kept turning the pages, hoping for a way out’ Leah Swann, author of Sheerwater

‘Through captivating prose and an intricately crafted plot, After You Were Gone explores the complexities of what it means to be a mother: the joy, the rage, the floundering – and the desperate, unquenchable love’ Amy Suiter Clarke, author of Girl, 11

‘An elegant, powerful and utterly compelling thriller. The best book I have read all year’ Lucy Christopher, author of Release

‘After You Were Gone cleaves open ideas of friendship and family, revealing the complex inner workings of our closest relationships. Wakefield achieves what all good crime writers aspire to do: she forces the reader to stress-test their own sense of morality. She looks you in the eye and asks, what would you do if the unthinkable happened? What would you sacrifice? How far would you go? At once tense and atmospheric, After You Were Gone is also brilliantly plotted and populated with complex characters. An exciting new voice in Australian crime’ J P Pomare, author of The Last Guests

‘A riveting read… Breathtaking’ Sisters in Crime

‘This is how to write a psychological thriller; stylish prose in a warts-and-all tale… Wakefield makes a seamless transition into the adult genre’ Herald Sun

‘Chilling and laced with dark suspense’ Australian Women’s Weekly

For Allayne

2007

CARAVAN PARK INFERNO LEAVES NINE DEAD, SUSPECT AT LARGE

FIRE CLAIMED THE lives of nine people including three children and a police officer, when a section of Far Peaks Caravan Park burned to the ground late Sunday night. Following an arrest on suspicion of arson, a suspect was taken to Far Peaks District police station, from where she escaped custody.

Around 11.20 p.m. police were called to attend reports of a burning vehicle located in the main car park. A second explosion was heard minutes later, resulting in an intense fire that destroyed four residential caravans and burned through a patch of adjacent scrub. Police have confirmed both fires were deliberately lit, accelerated by gas cylinders and fuel stored at the location.

First responder Constable Tristan Doyle arrested suspect Sabine Marie Kelly (17), a resident of the caravan park, who was apprehended leaving the scene. Kelly was taken to the police station in Main Street, where she escaped. She was last seen running east along Cooke Terrace and may be driving a silver Commodore wagon (SLE449), which was reported stolen this morning.

While the nine victims have yet to be formally identified, police have confirmed one of their own, Constable Logan Billson, died trying to save other victims. Billson was the son of Sergeant Eric Billson, a respected veteran officer who has served Far Peaks District for thirty-five years.

‘This is a tragedy for our community and for my family,’ Sergeant Billson said during this morning’s press conference. ‘I ask for privacy to grieve and for the community’s support and vigilance. The suspect is injured, possibly armed, and very likely dangerous.’

The tragedy has devastated the community. According to residents, the suspect’s younger sister and mother, a known drug dealer, were killed in the fire, leading to initial speculation that the incident was connected to organised crime. The subsequent arrest of Kelly, a local teenager, came as a shock to many.

Several crime scenes located in and around Far Peaks Caravan Park have been cordoned off pending a full investigation. Sergeant Billson asked that those not directly involved with the investigation avoid the area. Police are calling for witnesses, particularly anyone who might have information that could lead to the arrest of the suspect.

Sabine Kelly is described as seventeen years old, 167cm tall and approximately 55 kilos, long, curly blonde hair and blue eyes, last seen wearing a white dress. It is likely she sustained burns during the fire and may seek medical attention.

‘Anyone found to be hiding or assisting the suspect in avoiding formal charges will face charges too,’ Sergeant Billson said. ‘It can’t be stated strongly enough – it’s for the safety of the community that Sabine Kelly is found and returned to custody.’

2019

Sabine

The cliffs at Shallow Bend are painted red and gold; the willows sweep the water with loose limbs as the river brings Sabine home.

It’s the last day of summer and change is coming. Time moves slowly on the river – she hasn’t seen her grandfather since late winter, but it seems like longer. Pop keeps an eye out for her, but his hearing isn’t what it used to be and he sleeps like the dead. Sabine has mastered the art of cutting the houseboat’s engine, reading the current – her last visit, he didn’t know she was there until she had steeped a pot of tea and set the mug in his hand. He won’t call her, won’t pick up if she calls. It’s for her protection, he says. She thinks it has more to do with his distrust of technology. They have that in common. Pop believes microwave ovens can record conversations – he blames his cancer on the one she gave him. The cancer has gone and he stashed the microwave in the shed, its inner parts buried in the midden for good measure. He eats his meals cold, straight from the can.

Blue sits in his usual spot at the helm. He turns his back on the land and stares wistfully at the water, as if to say this can’t be right. He’s more seal than dog. Won’t eat red meat, only fish and occasionally chicken. Kibble is an abomination. Sabine often catches him nosing biscuits over the side of the houseboat for the carp.

She looks around.

Pop’s tinny rocks gently in her wake and the orange flag tied to the jetty post reassures her the area is clear of surveillance. The houseboat drifts into a space near the opening of the backwater; a soft bump and the rear swings around.

Blue loses his balance, his claws scrabbling on the deck.

Sabine laughs and Blue, indignant, barks once. She shushes him with one finger. His bark sets off the kennel dogs across the river and for the first time he shows interest in going ashore.

‘Leave it,’ Sabine says softly, and he settles on his mat.

She leans over to scratch at the peeling lettering on the side of the houseboat. Kirralee. She had wanted to rename her, but Pop said there were at least five other boats he knew called Kirralee and that was a good thing. Keep it simple, hide in plain sight and all that.

She would’ve named her Aria if things weren’t the way they are.

As houseboats go, this one is no beauty: a single cabin with a double bed, kitchenette and couch, some cupboards for storage and a toilet cubicle. Utilitarian. She floats. The deck is rotting in places and a section of railing broke away last week, but it has near-new pontoons and the engine runs like a dream.

The railing needs to be fixed. Non-compliance can draw attention from the water police, particularly during the last days of summer, when the townies are out and about in their speedboats and on their jetskis, stirring up mud. In a couple of days, there’ll be fewer patrols – she’ll be able to relax her vigilance.

Smoking a rollie cigarette, her hand cupped over the glowing tip, Sabine waits until the sun slips away. She doesn’t smoke often and the tobacco is stale, fizzing like a sparkler. Sometimes she has to travel well after sunset to find the right place to moor, which can be risky. Tonight her timing was just right.

Blue dozes, head nodding, slit-eyed.

Pop’s property isn’t as secluded as it used to be. His triangle of land, five or so acres with a hundred metres of frontage, has been squeezed by development on either side: two-and three-storey mansions, sloping lawns, towering lights that send fragmented beams across the water. Pop’s riverfront is a black expanse in the centre. No glimpse of the green weatherboard shack from here, apart from the aerial on the roof. He has let the blackberry grow wild to form a wicked hedge, like something from a fairytale.

Pop likes to point his rifle at the kids who sneak through the fence to pick berries. Wouldn’t shoot nobody, he says. The rifle is never loaded. He just gets a kick out of taking aim. Little bastards deserve it – they can read the signs. PRIVATE PROPERTY. KEEP OUT. GUARD DOGS ON PREMISES. NO VISITORS. TRESPASSERS WILL BE SHOT. GO AHEAD, MAKE MY DAY.

Sabine smiles grimly, worried this might be the time she turns up to find he’s incarcerated, or dead in his chair. Three, maybe four times a year she checks in: although there have been fewer raids over the years, the risk of surveillance is ever-present.

The light turns deep blue and quiet falls. There’s always a brief hush at this hour, changeover, when the daytime creatures clock off and the nocturnal animals start creeping about. She spots movement – a feral deer drinking at the river’s edge – and claps her hands to scare it away before Blue takes off on a chase.

She checks the horizon. Dark enough now.

In the cabin she stuffs a bag with toiletries and a change of clothes; it’ll be a luxury to take a bath. She locks the door behind her and disembarks to tie off. Blue hits the bank without getting his paws wet, but Sabine misjudges – her feet sink into the grainy sand and her shoes suck in water.

‘Fuck it,’ she says under her breath.

‘Mind your mouth and stay where you are.’

Sabine’s heart misses a beat before settling. ‘You gonna shoot at me too, you old bastard? I thought you were deaf?’

‘Can read your lips all right,’ Pop mutters, emerging from the murk. ‘Watch where you step – tiger snake’s claimed that spot.’

Sabine pulls her foot from the sand with a squelch. ‘He’ll be curled up asleep, probably.’

‘The devil don’t sleep,’ Pop says. He flicks on a torch and plays the beam over the bank to check. Just as quickly, he turns it off. ‘Come on, then.’

Blue waits. When Sabine clicks her fingers he follows at her heels.

Pop leads the way. After seventy years on the same patch he finds the path easily, even in the dark. The shack is on Crown land and his is a life-tenure lease, but at seventy-two his life is running out. No Kelly in recent memory has lived past seventy-five. Sabine knows that’s the thing bugging him lately: he’s got nothing to leave her, apart from meagre belongings and an ugly boat, and even if he did own the land she wouldn’t be able to claim it.

‘Can’t cark it. Those vultures are waiting,’ he said once, narrowing his eyes at her. ‘Can’t die peaceful-like until you get your shit together.’

For Pop, getting her shit together would mean to properly disappear – obliterate her name, find a real man to take care of her, never come back here again. To Sabine, it means something else entirely. She has managed just fine for twelve years. Why stick your head up when you have everything you need in the hole? For now, she’s just happy Pop’s mean old heart is still beating.

‘Sorry it’s been a while,’ she says.

‘The river takes, the river brings back. That’s how it is.’ He stumbles and rights himself.

He’s thinking of Nan. Sometimes the river only takes.

The shack looms ahead: an unfriendly building with a drunken lean to it, painted dark green without any bogging up or sanding back – every five years or so Pop just adds another layer to glue the place back together. He has a single propane lantern burning in the front window and three solar lights staked near the steps. Electricity’s too expensive, he says, so now he runs gas and a generator only when he needs it, and he’s going to need it now because Sabine has been dreaming of the bath for months.

‘You’ll want to soak yourself,’ he says, as if he can read her mind. ‘I’ll crank the gas. Leave that dog out.’ He heads off to the shed.

Sabine settles Blue on the porch, slips off her wet boots and lets herself inside.

Nothing has changed. The ancient floorboards throughout the cramped kitchen and living area have been mended in patchwork over the years, and she trips on a new section inside the door. The old couch is shaped like a hammock – Pop keeps it covered with layers of tartan blankets, not unlike the way he uses paint to keep the shack from falling apart. A film of coarse hair and dust coats everything. Pop only opens one window and the air is stifling, flavoured with the lingering odour of dog.

Blue’s dam Polly died a few years back – she crawled under the rainwater tank after being bitten by a tiger snake. Pushing seven years old and scarred from the previous litter, she shouldn’t have had her last: four fat pups, stillborn, and Blue the runt, barely breathing. Sabine blew in his lungs and claimed him as hers, lest he go the way of Pop’s bucket. Polly had been bitten twice before and survived. The last litter had drained the fight out of her, which accounted for Pop’s hatred of tiger snakes and his intolerance for Blue.

Sabine enters the bathroom. It’s tidy but not clean, and the enamel is cracking. She wonders if the bath will hold water. Pop wouldn’t know since he only ever uses the outdoor shower. She plugs the drain, runs the hot tap, hopes.

Steam rises. She adds more cold – it’s still 30 degrees outside – but not too much. It’s not really a bath unless you nearly poach yourself. When she looks for the shampoo to make bubbles, she finds a neatly folded towel and a lavender-scented bath bomb resting on the sink.

So Pop knew she was coming. Fucking river telegraph. Her eyes water, and it has nothing to do with the steam.

She closes the door and strips. The mirror is spackled with grime; she wipes a clean spot with a corner of the towel and peers at her blurred reflection. Lately her close vision isn’t great. She can’t read a book or a map without holding them at arm’s length. Too many years scanning the horizon. She probably needs glasses. She bares her teeth: straight and white against her tanned skin, but with a chipped incisor that makes her look as if she has been in a bar fight. Her cropped brown hair is showing blonde at the roots again. Is the suspicious mole on her collarbone turning black?

She shrugs. Couldn’t be any more malignant than the past she keeps put away. Optometrist, dentist, hairdresser – add those to the list of ordinary tasks she avoids. She can manage a razor, scissors and a pharmacy dye kit, but not doctor visits, beauty treatments or any kind of appointment that might enter a system. Her skin is tanned and dry and her muscles have become ropy from heaving and hauling, from riding the sway of the boat. She has too many scars to remember how they all got there, old cuts left unstitched.

She settles in the tub, shoulders submerged, knees protruding. The bath bomb fizzes on her belly. Pop will leave her as long as she needs, but she wants enough time with him to talk business and he gets jumpy if she stays too long. Plus Blue needs feeding. And she forgot to bring the batteries up for a decent recharge.

She pinches her nose and ducks her head under. When she comes up, Pop is rapping on the door.

‘Just a minute!’

‘Now, Beenie,’ he says.

It’s been so long since she’s heard him call her that. She experiences the conflicting sensation of heat in her extremities and, deep inside, a cold spike of fear.

‘What is it?’

She lurches from the water and levers her body over the side of the bath to sit on the mat, struggling to pull her underwear and shorts over her wet skin.

Blue’s barking his head off. For some reason he’s in the house.

Pop’s slamming cupboard doors. Looking for something.

She clasps her bra, yanks a T-shirt over her head and scrambles to her feet. Where are her boots? Outside.

She opens the door a crack. ‘Pop?’

‘Out the back. Take the dog and go.’

He’s cradling the gun. The ammunition box is on the kitchen counter, bullets spilling across the Formica. Blue’s barking has reached a pitch and tempo he reserves for pelicans and unwelcome guests.

‘Go!’

Pop raises the gun and walks steadily towards the door, aiming through the screen at chest height. He won’t let the person on the other side come in. She is terrified he won’t let them leave.

Sabine enters the kitchen on all fours, spidering across the floorboards. She crouches behind the counter.

‘Leave it,’ she hisses, and runs her hand past Blue’s nose.

On command, he drops and falls quiet. His eyes stay fixed on the screen door, still swinging after Pop barged through.

Outside the window, Sabine can see the silhouettes of two bodies, one pressing forward and the other backing away. Her palms are slick; water drips from her hair to pool on the floor, dark as blood. The air is heavy with humidity and danger. All signs are telling her to leave, like Pop said, but the realisation that the trespasser is a woman makes her pause. A long-dormant instinct is taking over, one that goes back to childhood – distract, de-escalate, protect.

With her hand, she stays Blue.

She crosses the room to the door and peers through the screen.

Her grandfather and the woman are moving slowly towards the far end of the porch. Yellow light from the lantern on the sill passes briefly over Pop’s features before he fades into shadows.

Sabine reels in shock.

The woman’s presence is disturbing enough, but Pop’s appearance takes her breath away. In the dark she hadn’t noticed the new lines and hollows, and his eyes, always bright, are now sunken and dull. In less than three months he appears to have lost a quarter of his body weight, and he’s moving as if each step is agonising. Compared to the woman, Pop seems the lesser threat.

The cancer. It’s back.

‘Face the wall,’ Pop says through gritted teeth.

The woman does as he says. Her mid-length dark hair is tied in a low ponytail, and she’s wearing a white blouse and navy skirt. Her stockinged feet are coated in mud. Everything about her screams desk job, government or cop. Pop has her by the back of the neck, the barrel of the gun pressed between her shoulder blades. She’s trembling, her head ducked in a show of submission.

‘Don’t turn around,’ Pop says.

‘Okay,’ the woman answers. ‘Okay.’

‘You’ve seen the signs,’ Pop growls.

She nods.

‘Then you knew what you were getting into.’

Sabine knows whatever happens next, they’ll be coming for her. She can’t let them take him, too.

‘Pop.’

He freezes, then jerks his head. ‘It’s her.’

The neighbour.

‘Go back inside,’ Pop mutters.

But it’s pointless – the woman has turned her head.

The tension inside Sabine releases. Pop is sick again. By the look of him, he’s never been closer to death. There’s only the inevitability of what will come.

She goes to her grandfather and presses down on the gun barrel, lowering it. For a moment he resists, but she puts her other hand on his shoulder and squeezes.

He’s shaking. There’s blood on his lips.

‘Pop,’ she says. ‘Enough.’

2019

Rachel

On the deck, by the river, Rachel is celebrating with a bottle of champagne. Aidan has finally agreed to the terms of the divorce settlement. She got everything she wanted: the river house, her super, the Audi and the cat, while he keeps the town apartment, the Jeep and his share portfolio. And Nadja.

Theirs is an old story. Woman, wife, mother reaches middle age, suffering resentment, loneliness and exhaustion from being everything to everyone, while trying to keep her husband and her career. Man, husband, father can’t keep his dick in his pants.

That’s her assessment of the situation.

It’s a still, humid evening; she’s starting to sweat in her rumpled suit. She takes a cube from the ice bucket, rubbing it on the back of her neck until the cube melts away. When she tries to twist her heavy hair into a perky topknot, it immediately uncoils to slither along her spine. It’s getting too long. Months have passed since she last bothered to colour her roots, where the dark-brown strands are shot with grey. She doesn’t need to lose any weight – the stress has taken care of those extra perimenopausal kilos – but a different hairstyle and some new clothes isn’t a terrible idea. One of those studded leather jackets, some hippie-style skirts. A tattoo, or a piercing. Rites, to speed up passage through the dark tunnel of divorce.

She laughs self-consciously. God, Rachel, is this a celebration or a wake?

Mainly she’s relieved the painful year-long mediation is over and it didn’t involve the kids. Ben and Alexis are twenty-three and twenty-five, respectively – far more civilised about their parents’ ugly divorce than she and Aidan have been, and more forgiving than Rachel about Nadja.

The champagne was a gift from her lawyer. Alexis left a voicemail message saying she’d see her in couple of weeks. Apart from that, there was no line in the sand, no real sense of letting go. For company, she settles for an unremarkable sunset, a glass of tepid champagne and one pissed-off cat called Mo, who has been winding increasingly agitated figure eights around her ankles and needs to be fed.

She glances back at the house. It’s too big for her on her own. When she and Aidan built it nine years ago they’d envisioned weekends filled with kids, the extended Weidermann family and, in the future, grandchildren. When they separated it was like somebody died. Even Lex and Ben stopped coming.

She accepts that the marriage breakdown is partly her fault, but she can’t get past Aidan’s confession that Rachel bored him. They were together for twenty-seven years and they’d barely spent any time together in the past ten – how could a person be bored by a spouse they rarely saw? That Rachel was tired, distracted, driven (most of the time) and distant (some of the time) she can believe. But boring? It hurt. It changed her self-perception, eroding her self-belief to the point that, when she was made redundant from the newspaper six months ago, she felt like a senior on the verge of retirement, not a forty-eight-year-old professional woman who had it all and then suddenly, devastatingly, lost it.

Well, not everything. She looks back at the house.

How hard she fought for it – the biggest prize, a home large enough for a family of eight, with three double guest bedrooms and a master suite, three bathrooms, two living areas and an expansive deck that steps down to the jetty. She has peace and quiet, freedom, independence, in an idyllic location. Then she thinks of the expensive solar panels and batteries that still aren’t paid off; she thinks about the mortgage, eating into what’s left of her redundancy package, her meagre freelance income and dwindling savings, before deciding not to think anymore.

The jetty. Mentally, Rachel adds that to her to-do list. She needs to arrange for it to be shortened by a metre, thanks to old mate next door.

Living on the river full-time took some adjustment, not least because of her nearest neighbour: Ray Kelly, batshit crazy, roaming his acreage with a .22 slung over his shoulder like some kind of vigilante hillbilly. He caused her no end of trouble with the council, lodging complaints about anything and everything: the proximity of the septic tank to the boundary, the wattage of the sensor lights, the colour of the fence and the length of the jetty. When a pair of Rachel’s underwear blew over on a windy day, he brought it to her attention by impaling them on a pitchfork.

Now the last of the sun’s rays are fading; any moment the deck lights Aidan had installed will come on. On that she concedes Ray Kelly has a point – they light up the deck like a football stadium.

She throws back the last mouthful of champagne, goes inside and turns off the main sensor switch. When she settles back in her chair to pour another glass, a houseboat chugs past.

It’s after sunset – they’re cutting it fine, she thinks.

As the houseboat passes, the lights turn off and the engine sputters out.

Rachel leans forward in her chair, straining to make out the darkened shape as it drifts towards the bank on the other side of the fence. Every part of her is on high alert.

Is it her? Is she back?

Until four years ago, Rachel and Aidan had been unaware of the connection between their unpleasant neighbour and the fugitive, Sabine Kelly. Their busy lives meant the river house was mostly used as a weekender, but Rachel had decided to take a midweek break. It was the raid that tipped her off – the road choked with police vehicles, suited-up officers pawing through the bushland on the other side of the fence, dogs baying. At first she’d assumed it was drugs, but a little digging produced the link. She knew of the Caravan Murders case, but only in general terms. A fire in a caravan park, nine people dead, a teenage girl on the run. Back then crime wasn’t her beat. But further reading led her down a rabbit hole, and it was then that things got interesting.

Rachel never forgets a face, and one look at a photo of Sabine Kelly had given her a jolt of recognition. She’d seen the girl before, a couple of years earlier, on the river – just a glimpse as she was leaving Ray Kelly’s jetty.

Now she knows everything about the case. Her mild interest has grown into an obsession. It’s the kind of story that could make her career, but years have passed since that first sighting and she has almost given up hope that Sabine Kelly will return.

Rachel stands and peers into the dark. Her nerve endings are on fire.

Could this be her, after all this time?

She wouldn’t call what she does surveillance. It started as a way to pass idle time, and she’s had a lot of that since the separation and her redundancy. She watches people – always an observer, uncomfortable with people looking in at her. Staring out at the river is like watching a series of vignettes of other people’s lives. Families and friends. Lovers. Parties, fights and near-death experiences, all rolling past like a showreel. On a clear day she can overhear entire conversations.

She reaches for her phone, heads down to the riverbank and starts a video recording.

The houseboat drifts closer to the bank near the entrance to the backwater. Its rear swings around. A slight figure steps out of the cabin. A dog barks, setting off the dogs across the river. As the sun sinks behind the cliffs, the figure slouches against the railing and lights a cigarette. Something in the easy way the figure moves about the boat reminds Rachel of a man, but it is the hips and the slender neck that tell her it’s a woman. For a long time the figure is still, waiting.

Rachel zooms in, but the image is too grainy. Her new fence stops five metres from the water – in accordance with council regulations – but Ray Kelly’s barbed wire-fence continues a metre in.

It isn’t far. It isn’t deep, she tells herself.

The usual panic rises, but her curiosity wins. She kicks off her heels and wades into the dark water, feeling her way along the wire until she reaches the almost-submerged post. Mud squelches between her toes. She hates the feeling, but forges on, scrolling through headlines in her mind – an old habit she can’t shake.

Bitter ex-wife wades into river to end it all.

Unneighbourly feud ends in bloodshed.

Sad-sack ex-journalist drinks too much champagne and drowns.

Or, Body of woman in river remains unidentified.

The last one’s a winner. Everyone loves a Jane Doe.

The current is fickle in this part of the river, the curve of the bend sharpest here – all manner of flotsam washes up on her frontage. Once, she found a kayak, no passenger, with a lunchbox containing a cheese sandwich and a minibar-sized bottle of Jack Daniels; another time it was the bloated, stinking carcass of a bull. Everything comes up to float eventually.

She takes another couple of steps, her blouse clinging to her sweaty skin. The water laps at the hem of her skirt, soaking the fabric and travelling to her hips – her no-nonsense, divorce-paper-signing, don’t-fuck-with-me outfit. She’s still wearing stockings, for God’s sake.

She stumbles and drops her phone into the water. She snatches it before it sinks, but it’s soaked. Tucking the phone inside her bra, she rounds the post, feeling her way to the bank on Ray Kelly’s side. There’s plenty of cover here, but it’s hard going: woody blackberry bushes tear her skin and she trips on twisted roots. She’s worried about the dog on the houseboat: will it hear her?

Once her feet are clear of the water, she stands completely still.

‘Fuck it.’ Clear as day.

Rachel crouches, all ears. There are two voices – the gruff grumble of Ray Kelly, and another female, husky one.

Her heartbeat quickens. It has to be her.

Typical. The story of the year washes up on her shore and the only resources she has at hand are her stubborn ambition and an outdated iPhone. And she has backed herself into a corner here: the angle of view is obscured by foliage and the trees’ deep shadows.

They’re on the move now, their voices fading.

Rachel looks across the fence. The safety of the river house, lit up like a Christmas tree, beckons. She should go home, call the police, but then this might end up as someone else’s story. She’ll miss her shot, and in any contest Rachel always aims for the biggest prize.

It takes long, arduous minutes to navigate her way through the dense shrubs to the rectangle of dead grass behind Ray Kelly’s shack. A faint glow through the nearest window illuminates what looks like a living room and kitchen, and a hallway at the rear.

Hunched behind a bush, she watches as the old man emerges from the shadowy doorway of a shed to the right. He makes it halfway to the porch before turning back, muttering, and pulls the shed door closed to lock it with a key. He pauses, searching the darkness in her direction.

For a moment it feels as if they’re staring at each other.

Rachel presses further into the bush, heart drumming.

Kelly climbs the steps to the porch.

Once he’s inside, she releases her breath and slinks across the lawn, heading for the darkened window at the side of the house.

Too late, she remembers the dog: as if summoned, it appears as a silhouette, seconds before erupting. The barking sets off an echo across the river and Rachel freezes, wondering if the animal smelled her fear before it heard her footsteps, and thankful that there is a door between them.

Suddenly the dog is hauled back and the door swings open to reveal a more terrifying silhouette: Ray Kelly with a rifle.

Rachel scrambles to her feet.

Kelly moves fast for an old guy carrying a heavy weapon – he has her by the collar before she has taken five steps, her bare feet scrabbling in the dirt like the dog’s claws on the floorboards. Her skirt rides up. She reaches behind her head, gripping his hairy wrists to relieve the pressure on her throat, choking out a protest.

‘Let me go!’

Without uttering a word, he drags her across the lawn. At the porch he lets go, only to shove the barrel between her shoulder blades and force her to stumble up the steps.

Rachel spins to face him, hands up, and backs away to the far end of the porch. A dead end.

Kelly jabs at her with the gun. ‘Face the wall.’

She does as he says. Automatically she places her palms flat against the wall and widens her stance, as if she’s about to be frisked.

Kelly has one hand pinching the back of her neck. The other is pressing cold steel against a knob of her spine.

Rachel ducks her head. A tremor starts at her jaw and spreads, earthing through her feet like an electric shock. It’s not her life that passes before her eyes, but her bloody, violent death.

Stupid. Stupid. Stupid.

‘Don’t turn around,’ Ray Kelly growls.

‘Okay,’ she answers. ‘Okay.’

‘You’ve seen the signs.’

She nods.

‘Then you knew what you were getting into.’

‘Pop.’ Almost a whisper.

Under his breath, ‘It’s her. Go back inside.’

A mad pulse beats in Rachel’s skull. Her bladder is ready to release. She looks down at her feet, pale and squashed inside the wet toes of her stockings.

‘Pop,’ she hears. ‘Enough.’

There’s a heavy pause. Then the cold press of the gun loosens and Rachel slumps against the wall. A sharp fleck of paint wedges under her fingernail.

A creak, followed by a slamming door. Now it’s only the two of them.

‘Take the gravel path. It’ll bring you back out on the road.’ Kelly pokes her right glute with the gun. ‘Don’t come here again, understand?’

Rachel nods.

She has been here before, snooping around. She knows the path; she knows the front gate is topped with razor wire, but there’s a gap between the rails wide enough to slip through. She keeps her hands raised and moves sideways down the steps until she feels stones under her feet.

‘Keep going.’

Kelly follows her around the side of the house. She picks her way gingerly along the narrow path, flanked on both sides by dense shrubbery. Away from the dim light of the lantern, it’s dark.

‘I can’t see where I’m going,’ she bleats.

He grunts. Plink. Chick.

Rachel recognises the distinctive sound of a Zippo lighter. The path ahead is now illuminated, their long shadows merged into a single lumpen mass. Without turning around, she can tell he’s listing to one side, limping. They emerge from the path onto an overgrown driveway. His truck, with a flat front tyre, is parked on the other side of the fence.

‘There’s the gate,’ he says. ‘Show yourself out.’

‘I’ll do that.’

‘I’d have shot you for trespassing. I’d be within my rights.’

Rachel’s first instinct is to set him straight about her rights. Beneath the terror is a welcome flicker of rage. She chooses to mitigate the danger by lying.

‘I was only after your help.’

He waits, the flame dying, as she climbs through the gap between the rails. When she turns around, he is smaller than she remembers. Thinner. He is no longer carrying the gun.

‘What help?’ he says, and flips the lighter lid down to extinguish the flame.

Rachel can only see a golden halo on her retina; he’s a disembodied voice in the blackness. ‘Rats. In my roof,’ she says.

That part is true.

His eyes fix on her, then lose focus.

Rachel has heard it too: the low rumble of an engine.

‘Can’t poison ’em,’ Kelly drawls. ‘You poison ’em, they’ll die in your cavities and you’ll have to live with the stink. Then you’ll get the cadaver flies – thousands of ’em. So many of the bastards you’ll think your house is possessed. Rats gone, but you’ll have something worse. You’ve gotta cull your fruits – those pears you’ve got hanging there, the lilli pillis and them figs. That’s why they’re hanging around.’ He looks over his shoulder. ‘And they come for the scraps. You got chooks?’

‘No.’

She knows what he’s doing. He has just babbled more words than she has heard him speak in a year – so his fugitive granddaughter can slip away.

‘Right. What do you suggest?’

‘Trap ’em.’

‘Like, in a cage?’

He nods. ‘It’ll take a while – rats are suspicious, gotta get used to something new. Eventually they’ll get curious and investigate, then you knock ’em on the head or drown ’em in a bucket.’

Rachel’s feet are bruised, possibly bleeding. Their nearest neighbour with a light on is a hundred metres away, further by road. She is not safe here. Her phone is ruined. She needs shoes.

‘The woman—’ she starts.

His expression is like a door closing. ‘I’ll drop those traps around.’

‘I appreciate it.’

Kelly spits to one side, then he’s gone.

At the house, Rachel is grateful for the security system that tracks her movements. From the back gate, along the driveway, through the entrance and down the hall until she reaches the kitchen, the lights switch on ahead of her and off again once she has passed. The outside deck is still a black spot; she turns the sensor switch back on, flooding the area with light.

Trembling all over, she pours a packet of Arborio rice into a mixing bowl and buries her phone in the grains. Ben has assured her it works. She hopes so, otherwise she’ll have to pray there was enough signal for an immediate backup to the cloud.

Call the police, Rachel.

And tell them what exactly? That she trespassed? That her neighbour pulled a gun on her? Reporting certainly won’t help her get to Sabine Kelly.

Mo materialises from his cat igloo, tail twitching with irritation.

Equally irritated, Rachel presses the button on his auto-feeder with her foot. He has never got the hang of working the damned thing. A handful of biscuits shoots into the bowl, and Mo gives her another glare before deigning to eat.

She picks up the kitchen handset and dials.

‘Lex?’

‘Hey, Mum. You’re on the landline? What’s up?’

She registers the quaver in her daughter’s voice and fears Lexi will forever be anxious about her calls. Rachel has drunk-dialled on more than one occasion; she has overshared – her anger over Aidan’s cheating, her grief over the separation. She promised herself she wouldn’t do it anymore.

‘My mobile got wet. Everything’s fine – I just wanted to hear your voice.’

‘Here I am!’ Lexi says. ‘What are you doing?’

Rachel inspects her ruined pantyhose, the mud spattered up her calves, her bleeding fingernail. ‘Oh, I’ve been watching the sunset with my friend Veuve Clicquot,’ she says, too brightly. ‘I was thinking, I need a couple of days in the city over the weekend. We could house-swap? You can come up here with your friends?’

She has voiced her fear – that Lexi doesn’t want to be at the river house while Rachel is there.

‘It’s a three-hour drive there and back. I can’t afford the petrol,’ Lexi says. ‘Anyway, I’ve already made other plans. Sorry.’

‘It’s fine. Another time.’

‘Sure.’

‘I’ll let you go.’

What a loaded statement, she thinks. If you love something, set it free.

‘Bye, Mum.’

‘Bye, beautiful.’

Rachel hangs up, leaving a smear of blood on the receiver. She turns off all the lights, checks the windows and doors.

There are too many. She had pored over the design of the house, spending hours moving a chair into different positions and holding up a cardboard frame to find the right angle. The reward is the perfect panorama, a one-hundred-and-eighty-degree view of the river’s changing moods and colours.

The price is that everyone can see in.

2019

Sabine

Sabine moors the houseboat in Dixon’s backwater – not too far along in case she needs to move again quickly. She has made it about three kilometres downriver from Pop’s place in the dark, only the faint light of the moon to guide her. It’s unlikely there are any patrols this late, and she hasn’t received any call-outs over the radio – locals, warning each other – but it’s too risky to travel any further.

Like many of the locals, Dixon has put up his own sign to deter entry: KEEP OUT. PRIVATE PROPERTY. SHALLOW WATER. Although the sign is less hostile than Pop’s, it’s just as effective. This is council-owned land, and the backwater is deep enough, but few would have the balls to follow her in here. Dix likes to think this part of the river is his, repainting the sign whenever it fades, so there’s no confusion. This time of year he’ll probably be camping at the river’s mouth, catching mulloway. If she wants, she could go up to his shack, find the spare key and have a shower, but there’s a chance he’ll be there. When he’s drinking, he can’t keep his hands to himself.

Blue likes to sleep inside at the foot of the bed, but tonight she puts his mat on the deck so he can keep an ear out. When she closes the door on him, he turns circles, whines for a bit and finally settles.

Her body is tired, but her mind is still whirring. She’s worried about Pop. It’s a twisting, constricting sensation inside her, one she recognises as helpless panic.

She undresses, letting her damp clothes fall where she stands. The faint scent of lavender rises with the heat of her skin and she finds undissolved bath crystals in her navel. She crawls slowly across the bed, unmade since yesterday, and pulls the curtains open to let the moonlight spill across the sheets.

She lies awake for a long time.

Pop is in danger because she was sloppy. Twelve years of chugging from place to place and evading detection has made her complacent. It doesn’t help that the river is more populated now – the old shacks have been torn down and replaced by mansions, built by people who have nothing better to do than sit on their decks all day and poke their noses in other people’s business.

Pop said the intruder was his neighbour. It’s not enough by itself to send her back into deeper hiding, but there was something about the woman’s demeanour that set Sabine on edge – she was too composed, too watchful, even with the muzzle between her shoulders. When Pop sent her packing he probably thought that’d be the end of it, but Sabine has a radar for trouble and she suspects there’ll be some coming.

When she recalls the way Pop looked – shrunken, ancient, as if the life was being drained from him – she chokes up. She had a taste of this fear when Pop first admitted he was sick, but the last time she saw him he said he was better.

He lied then, and he’ll lie under oath before giving her up. She won’t let him do it. However little time her grandfather has left on this earth, she doesn’t want him spending any of it in jail for aiding and abetting a fugitive.

She should be on her way already – upriver, downriver, inland, anyplace but here – but the blood tie is too strong. It always pulls her back.

Sabine has always been a heavy sleeper, and Blue doesn’t bark a warning, which is how Ryan makes it all the way to her bed before she wakes.

Through slitted eyes she finds the shape of him in the murk. For a split second she wonders how he got in, what’s happened to Blue, why she didn’t sense him, before the rush hits and she kicks her way out of the tangled sheet. In one clean movement she shifts to a crouch before launching herself at him, her legs a vice around his waist.

Now Blue barks – a series of excited yips.

‘How did you find me?’

‘Too easy,’ he says. ‘You’re not far enough in.’

He knows all her mooring places, and he knew she was headed down Pop’s way. But he can’t know what happened tonight and she won’t tell him. She doesn’t like him to worry.

‘Maybe knock?’

‘Maybe lock the door?’

‘If my knife was under the pillow, I might’ve stabbed you.’ She releases her grip and lets herself fall onto the bed. ‘And it’s after ten. You shouldn’t be on the river this late.’

His eyes flick to the bedside drawer where she keeps a knife – a filleting knife, but it would just as quickly gut a man as a fish. She raises herself to her elbows, lets her bare legs fall open, and that’s where his eyes travel next.

‘I’ve missed you,’ she says. ‘It’s been three weeks.’

‘First chance I’ve had to get away.’ He kneels, bracing with one hand on the side of the mattress, the other running along her inner thigh.

Sabine shivers. Her head flops back.

He pulls her underpants to the side and strokes her lightly before peeling them down one-handed, alternating left and right until they slip off her feet. His hand is back, rubbing. He climbs onto the bed, positioning himself above so he can see her expression, gently sliding his middle finger inside her. He stays so still she forgets to breathe. She is full and empty at the same time. She squirms against him, but he clamps her down with his big palm and leans down to kiss her lower lip. A sigh, and she gives in. He might hold her there for five seconds or five minutes – it depends on his need, not hers. It’s been so long he could go either way: soft and slow because he wants her to be patient, or fast and hard because he can’t be.

Sabine has to take herself somewhere else to wait for him – the place she always ends up is at the beginning: a single mattress in his bedroom, their bodies young and undefined, her response tentative and his touch less sure but still a revelation. She remembers the feel of his adolescent stubble on her skin, and his expression when her breath quickened as he realised he was doing something right.

It’s the same look on his face now. She has come, neither of them moving. He feels her tension and release on his finger and it surprises him.

It doesn’t surprise Sabine.

Dee put her on the pill at fifteen, said it would be shit the first time and probably the hundredth too, and warned her not to ruin her life by having a baby at sixteen like Dee had. Any relationship was hard enough all on its own; a baby was a passion-killer. Guys only ever wanted one thing. Only give if you were willing to take, too. Don’t fall in love with the first guy you sleep with, hold something back.

Dee said a lot of stuff that didn’t turn out to be true and Sabine has never held back, not the first time and not since.

Ryan smiles and pulls away, delighted. His weight leaves her, but only long enough to remove his clothes. It isn’t over. They have all night.

The way she feels about him – it never fades, never changes, never gets old. In some ways every time feels like the beginning. She knows he’ll never be with anyone else, but she has to remind herself that one day it will end.

With Ryan it has always been easy. It’s everything else that’s hard.

As soon as she hears the magpies’ pre-dawn song, Sabine is awake. She has trouble sleeping in, even when it’s still relatively dark, like it is now in the deep shade of the backwater.

They were up late. She stretches and yawns, her muscles throbbing with a pleasant ache.

Ryan is on his side facing away from her, his lower body covered with the sheet. He’s just come off a ten-day straight shift at the mine. He probably won’t wake for ages. Ordinarily she adjusts her rhythm to match his, even if it means hours lying next to him, watching him sleep. But today she’s antsy. If she takes Ryan’s tinny, it won’t take long to motor back to Shallow Bend for a quick check on Pop.

She rolls out of bed.

Leaving Ryan makes her chest hurt, and the sentimental part of her wonders why love so often feels like pain. Her more pragmatic side knows why – love can kill you. To tie your life so completely to one person is not a wise strategy for survival.

She shrugs off her melancholy and kisses his knee, poking up from beneath the sheet.

Quietly, she grabs clean clothes, a large straw hat and a bottle of water. Behind the privacy screen of the outdoor shower, she rinses, dries off, and pulls on a pair of shorts and a T-shirt, slipping an oversized cotton shirt over the top. The shirt makes her look bigger than she is. The hat will cover her hair and conceal much of her face.

She steps into the tinny and clicks her fingers. Blue follows. She uses the oars to paddle out of the backwater before starting the outboard and put-putting into the river proper. It’s too early for much traffic and she has this stretch to herself: the low bank to her right, the vertical cliffs to her left, a cloudless sky above. The air is still fresh with morning chill.

Blue splays his paws on either side of the bow and lifts his nose to scent the breeze, showing interest in some movement on the bank. Another deer, head up, nose twitching.

‘Not today,’ she says.

Blue throws her a disgruntled look, but she can’t have him off overboard when she has to keep moving. He’s spoiled. Most days she’s happy to sit in one spot for hours, letting him wander. It bothers her that she has so little awareness of time passing – days have turned into weeks, weeks into years. In another month she’ll be thirty, not much younger than Dee was when she died. When you rarely talk to people or use technology and you don’t read the papers, it’s too easy to pretend the world hasn’t changed.

The tinny comes around Shallow Bend. Pop’s flag is still fluttering from the jetty post, but Sabine cuts the motor, readying herself to turn around at the first sign of unusual activity.

Everything is quiet.

At the joint adjacent to Pop’s, she spots the light poles, taller than the remaining willows, and the rows of London plane trees planted along the curved driveway. She wonders how on earth permission was granted to remove the red gum that was there. It would have been over a hundred and fifty years old.

Money, she supposes. Rich people can get away with things poor people can’t. Pop said the neighbour woman asked him to move his rainwater tank because it looked ugly next to her fence. Look at her jetty, sticking out too far, look at the sandbags she brought in to make her own private beach – doesn’t she know the river will do what it wants?

Behind her the Old Mary paddleboat is heading upriver.

Sabine makes Blue drop to the bottom of the tinny and steers closer to the bank, cutting the revs to slip under the cover of the willow branches. Too late, she realises the beach sand has eroded and piled up here. Scrape. The tinny bottoms out.

She’ll have to get out and give it a push. Fuck.

When she throws her leg over the side, Blue takes it as a sign he should disembark, too.

‘In. In,’ she hisses, but he has his snout in the shallows.

He comes up with an old tennis ball and bounds ashore to give his signature full-body shake.

The sound, thankfully, is drowned out by a blast of Old Mary’s horn. When the paddleboat’s wake slaps the bank, Sabine jumps out, turning the tinny and giving it a hard shove before hopping back in. She gives a low whistle.

Blue has disappeared.

As she looks back, a tortoiseshell cat shoots from under a boat trailer parked behind a shed.

She spots Blue on the beach, his tail stiff as a rudder.

‘Leave,’ she shouts. ‘Blue, leave it.’

He’s already off after the cat, which is airborne and clearly in fear for its life. Blue sends sand flying as he claws his way along the beach and up a steep retaining wall, yelping like his tail is on fire. Sabine knows there’s nothing she can do but hope the cat is smart enough to find safety up a tree. Not that Blue will hurt it if he catches up, but the poor thing might die from shock in the interim.

The woman from last night is standing on her deck wearing a bathrobe, a mug in her hand.

Sabine turns the tinny around and pulls up alongside the jetty.

The woman is yelling, waving her arms. ‘Get! Get, you mongrel!’

Sabine jumps out to tie a quick knot and races up the path towards the house. By the time she reaches the back door, Blue is half in and half out of the pet flap, trying to follow the cat. She pulls him out by the hind leg and gives him a hard shove in the chest. Once she makes eye contact he backs off, whining.

The woman has followed her and reaches down to lock the flap. ‘Lucky he didn’t fit,’ she says, panting.

Sabine’s hat has blown off during the chase. She keeps her eyes cast down. ‘I’m sorry. He won’t hurt it – he only wants to catch it.’

‘It’s not my cat I’m worried about. The last dog that took on Mo lost an eye.’ She crosses her arms.

‘Sorry again. I’ll get him out of here right now.’

The woman’s body language changes: she holds out her hand, smiling. ‘Rachel.’

Sabine shakes her hand briefly, offers nothing in response.

‘You’re Ray Kelly’s—?’

In her pause is everything Sabine has been worrying about. Coming here was a mistake.

‘I’m a family friend,’ she says. ‘I look out for him. Come on, Blue.’

The woman – Rachel – gestures towards an impressive teak outdoor setting. ‘I’ve just made coffee. Would you like to join me?’

It seats twelve, Sabine notices. There’s one mug on the table, and a lonely champagne flute with bright red smears around the rim. Sabine hasn’t worn lipstick since she was seventeen.

She shakes her head. ‘Thanks, but we really have to go.’

Blue is snuffling at the cat flap again. She taps his flank to get his attention and strides down the path, along the jetty, but once there she struggles to untie the knot.