Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

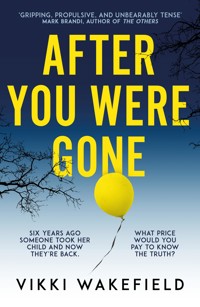

DISCOVER AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR VIKKI WAKEFIELD'S GRIPPING PSYCHOLOGICAL THRILLER What happens to a family when a child goes missing? In a busy street market, Abbie lets go of six-year-old Sarah's hand. She isn't a bad mother, just exhausted. But when she turns around, her daughter is gone. READERS LOVE AFTER YOU WERE GONE ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'Instantly gets your heart beating' ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'Will have you gripped from the beginning' ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'The three different storylines were perfection to me . . . I had a knot in my stomach' ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'A twist few will predict' Six years on, Abbie is in love and getting married. But her fragile peace is constantly threatened: not knowing what happened to Sarah. Then she receives a phone call from a man claiming to know what happened, but if Abbie tells anyone she'll never find out the truth. After You Were Gone is an edge-of-your-seat thriller that poses the question: How far would you go to find your child? PRAISE FOR AFTER YOU WERE GONE 'Gripping, propulsive, and unbearably tense – the best psychological thriller I've read in years.' — Mark Brandi, author of The Others 'An original thriller full of empathy.' — Sarah Bailey, author of The Housemate 'An elegant, powerful and utterly compelling thriller. The best book I have read all year.' — Lucy Christopher, author of Release 'The very best kind of thriller: tender and wise as well as pulse-poundingly tense.' — Anna Downes, author of The Safe Place An exciting new voice.' — J.P. Pomare, author of The Last Guests 'Elegantly written and utterly chilling. A dark and twisting novel of psychological suspense.' — Emma Viskic, author of Those Who Perish

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 475

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOR VIKKI WAKEFIELD

‘Gripping, propulsive, and unbearably tense – the best psychological thriller I’ve read in years.’ – Mark Brandi

‘An elegant, powerful and utterly compelling thriller. The best book I have read all year.’ – Lucy Christopher

‘An expertly crafted psychological thriller... need-to-know addictive propulsion...The ending felt just right.’ – InDaily

‘An original thriller full of empathy.’ – Sarah Bailey

‘After You Were Gone is the very best kind of thriller: tender and wise as well as pulse-poundingly tense.’ – Anna Downes

‘Spooky, believable, compelling. I kept turning the pages hoping for a way out.’ – Leah Swann

‘After You Were Gone cleaves open ideas of friendship and family, revealing the complex inner workings of our closest relationships. In doing so, Wakefield achieves what all good crime writers aspire to do: she forces the reader to stress-test their own sense of morality. She looks you in the eye and asks what would you do if the unthinkable happened? What would you sacrifice? How far would you go? At once tense and atmospheric, After You Were Gone is also brilliantly plotted and populated with complex characters. An exciting new voice in Australian crime.’ – J.P Pomare

BEFORE

When I was a child I believed there was a place where lost things collected, the way sea-drift found its way ashore to the same sheltered cove on our beach. I never knew if it was a story I’d heard or one I had made up, but I could picture it clearly: a black hole where time stood still and the lost things lingered – socks, shoes, purses, keys, missing pets – until people stopped looking for them and they faded from memory.

After Sarah was gone, I imagined her in that place. Suspended, sleeping.

Not knowing was like living inside a well with slippery sides and the occasional crack between stones, a foothold, a scrabbling place. I yearned for answers; I tortured myself, going over the things I could have changed if only I had been paying attention.

After Sarah was gone, I moved on, but I built my house around the well. While I was busy living, it sank deeper; the distance was greater, the light dimmer. This time the climb might be impossible, but I had no choice – I let myself fall.

My life is a story in two parts.

Before.

After.

The day my daughter went missing, we were at war.

Our two-bedroom, ground-floor unit in the outer suburbs was one of twelve, close to a busy main road. I wanted to go to a weekend street market. At the time I didn’t have a car, but the buses ran hourly and our stop was only a ten-minute walk away. The bus I wanted to catch arrived in fifteen minutes, but Sarah was still standing in the hallway, facing the wall, arms folded.

‘It’s going to rain,’ I said. ‘You’ll be cold. Put on some long pants and a jacket.’

She shook her head and stamped her bejewelled flip-flops.

I tugged at her dress – pink with a leotard bodice and a tulle skirt, more suitable for a fairy-themed party than an unseasonably cool day. I’d taken her to see the fireworks at the beach the night before and she was overtired and bad-tempered.

‘We’ll miss the bus. Quickly – get changed.’

She slapped my hand. ‘You can’t make me!’

I stepped away lest I slap her in return. ‘We’re not going until you do as I ask.’

‘I don’t want to go. It’s too far. The market is just stupid people and weird fruit.’

She flounced to her bedroom. Seconds later, I heard the chime of her jewellery box and the clack of beads.

I followed, taking deep breaths, and watched her from the doorway.

Sarah didn’t look much like me except for her skin tone and build: golden and quick to tan, slim but muscular. She could hold a handstand against a wall for five minutes and turn eight cartwheels in a row, but her hair was straight and dark, unlike my tight blonde curls, and so silky it slipped from a hair tie. She had fuller lips, inscrutable expressions, and eyebrows that threatened to meet. Fierce, independent and intelligent in a way that was spooky in a child, Sarah delighted in pushing me past logic and into pure reaction. If I lost my temper, she would smile.

‘Sarah, let’s go!’

I should have given in. If there was ever a moment in my life I could change, it was then.

But I listened to that infuriating chime, let my frustration build and peak, and by the time I’d dragged her from her bedroom, her graceful neck weighed down by a string of beads, she was crying. She grabbed her ever-present drawing supplies from the dining table – a leather briefcase that made her look like a tiny office worker – and tried to stuff her doll Annie inside. The catch wouldn’t close.

I wrenched the doll away and flung it on the couch. ‘I’ll just end up carrying her around. Leave Annie here.’

The police would ask me later if I saw anyone parked outside our block of units, if it was possible we were followed. I told the truth when I said I didn’t see anyone, but I was in no frame of mind to notice details. Even hypnotherapy only gave sharper, more painful focus to the things I’d done: squeezing Sarah’s hand too tightly, barking words I meant at the time and regretted later. The time I was trying to make up with long strides, pulling her along the footpath, was counteracted by her dragging weight. Sarah retaliated by plonking herself down, but I hauled her up by the armpits and recommenced our slow progress, unwilling to give her what she wanted – to go back home, and also, I suspected, to win.

We missed the bus.

The next one came after an hour of stony silence – Sarah scribbling furiously in her scrapbook, only breaking concentration to glare at me, covering her work with her arm so I couldn’t see. Another portrait of her monstrous mother, no doubt. Sometimes she gave me a ball gown and wings; more often it was bulging eyes, claws and sharp teeth. Her mutinous expression had softened, but it had been replaced by a resoluteness that made me fear she was building towards a humiliating public tantrum.

But I won.

We got off the bus and trudged the last five hundred metres to the market in Buskers Lane, a cobbled street flanked by the kind of narrow-fronted shops that relabelled and resold imported goods as designer fashion and homewares. It was a busy, crazy maze: outside the shopfronts, stalls flanked a pedestrian walkway just wide enough for four people abreast. It was mostly junk jewellery, deep-fried food, homemade crafts and cheap souvenirs, but Sarah loved the snow cones and I always headed for the fresh produce.

Despite my insistence that Sarah should wear appropriate clothes, I’d worn ridiculous shoes: wedge heels that made walking on the uneven cobblestones difficult. My ankles ached, but I was determined not to go home until I’d filled my shopping bag with weird fruit and taught my daughter a lesson.

‘Look, they have those crane kites you always wanted.’ Sarah was subdued.

‘No.’

‘Raspberry snow cone or Coke?’

She glared. ‘They make my teeth hurt.’

I pointed to a man making balloon animals, but Sarah was having none of it.

‘No.’

‘If you don’t snap out of it soon, miss, you’ll be going to bed at six o’clock for a week.’

It started to rain, a fine, floating mist that turned the cobblestones shiny and slick, enough to send people scurrying for cover.

I stopped at a stall to feel and smell the produce. The vendor held an umbrella over my head.

Sarah tugged at my arm. ‘I want to go home now.’

‘Then you’d better start walking.’ I said it without thinking, and picked up a spiky fruit. ‘What are these?’

‘Ritlee rambutan,’ the woman said. ‘They’re grown in North Queensland.’

‘Fresh?’

‘Came down yesterday. The jackfruit are from the Northern Territory. Very fresh.’

After choosing six rambutan and two jackfruit, I unfolded a canvas shopping bag and carefully placed the fruit inside. When I turned to speak to Sarah, she was gone.

‘Did you see my little girl?’ The vendor shook her head. ‘She was right here.’

I checked under the table. I looked up and down the street. No Sarah.

My temper flared again; instead of the expected tantrum, she’d pulled a disappearing act.

‘You saw her, though, right?’

She shook her head again. ‘No.’

‘She’s wearing a pink dress. If she comes back, can you tell her to wait here?’ I picked up my bag and ducked into a side street where I had a decent view of the area.

The rain was heavier now. My hair was sticking flat to my head and my arms were covered with goosebumps, but my primary concern – and I would later admit this to the police – was that Sarah was hiding somewhere, watching. I suspected she had witnessed my rising panic and found another way to punish me.

So I hid.

I stayed there for at least five minutes, hoping Sarah would blow her cover when she realised I had gone. I wanted her to be the lost child standing in the middle of the street, crying because she couldn’t find her mother. People would stop to help her. Still I’d wait, until her panic matched mine and she was inconsolable. I know I wasn’t the first parent to think about pulling this trick, but maybe I was the first to actually do it, and to have the stunt backfire in such a spectacularly devastating way.

Ten minutes later, I’d abandoned my shopping bag and my ridiculous shoes under a table. I never found them again.

I worked my way from stall to stall. ‘Have you seen a little girl?’ I described her hair, her beads, her dress. Held my hand waist-high. Told them her name. My feet were bleeding, my left big toe stubbed and shredded.

A crowd began to gather.

‘How long has she been missing?’

‘Could she have run off?’

‘Should I call the police?’ a woman asked.

‘I don’t know!’ I wailed. ‘No. Yes!’

Somewhere, an accordion was playing the ‘Beer Barrel Polka’ in an endless loop. I’d never get the tune out of my head. I watched a blue helium balloon detach itself from a bunch and sail away – I remembered that, but I couldn’t recall the faces of the people who tried to help.

It didn’t occur to me that she wouldn’t come back, or that we wouldn’t find her. My panic was still laced with guilt and, if I am honest, anger.

Despair came later.

Over the following hours the search spread from the laneway to nearby streets and parks; the police knocked on doors and searched shops, warehouses, roofs, even drains, anywhere a child might have been hurt or become lost. The sky darkened. More rain fell. There were baying sniffer dogs, portable spotlights that hurt my eyes, and faceless people who asked the same questions over and over, as if I might remember things differently.

It was that evening, when the sun had set and the only people left were those directly involved in the search, when I first heard the word ‘abduction’. Until then, it had been ‘lost’, ‘missing’ and ‘misadventure’. I was sitting on the rear step of a police van, a scratchy blanket wrapped around my shaking shoulders, feeling numb and alone. There were calls to be made, but first I had to accept that Sarah was really gone.

A tall, middle-aged man wearing a dark suit approached, holding out his hand.

‘My name is Inspector James Hooper. I’ve been brought in as the specialist investigator on your daughter’s disappearance.’

He had a warm handshake and gentle eyes. After the repeated questioning and blunt manner of the other officers, it was too much. I broke down.

He gave me a packet of tissues and sat next to me. ‘Ms Morgan, we have to consider that this might be an abduction.’

‘A what?’

‘Is there anyone who might have taken your daughter? Anyone she’d go with willingly?’

I shook my head. There was nobody, unless someone from her school happened to be in Buskers Lane and thought it was a good idea to convince Sarah to go with them. It seemed like long odds.

‘My parents live in Athena Bay. Jess – my sister – is in Greece.’

He checked his notepad. ‘You’re a single parent. What about her father? Is there a custody arrangement?’

‘He’s not in her life,’ I said. ‘You’d be wasting time looking in that direction. I couldn’t even tell you where to find him.’

‘Regardless, we’ll need names – anyone you can think of, any details, no matter how small or insignificant they might seem.’

‘No, no, it’s nothing like that. This is my fault – she wanted to go home. I told her to start walking, but I didn’t mean it.’

‘We’re checking all possible routes.’ He closed his notepad and tucked it in his shirt pocket. ‘Do you think she might have tried to make her way home, alone?’

I pictured Sarah’s habitual scowl, the stubborn set of her chin. ‘It’s possible,’ I admitted.

‘There’s some footage coming in. We’ll see what that shows us. I know you must have been over things a dozen times, but –’

I started telling him about the argument.

He interrupted. ‘I know those things. Tell me about her.’

She’s bright and wilful – we argue all the time – but she can be so sweet. She has a chickenpox scar on her right shoulder. Her bottom two teeth have just cut through. She believes in ghosts and fairies – she thinks she was a princess in a past life. She swims like a fish. Her earliest memory is of playing at the beach, and she likes hiding in small spaces but hates the dark.

We spoke for nearly an hour. I showed him photos of Sarah on my phone, and sobbed.

‘I won’t stop until we find her,’ he promised.

At seven o’clock an officer told me she’d been instructed to drive me home. I didn’t want to leave, but by then it was no longer a busy market – just a wet and lonely street, cordoned off from onlookers at each end. I clung to the possibility that Sarah had got lost. Perhaps someone had thought they were doing the right thing by taking her home. She might be waiting for me there, so I didn’t argue.

I sat in the back of the police car, shaking so hard my teeth felt loose. I chewed my nails and the cuticles bled. Until then I had ricocheted from one fraught moment to the next, but now reality hauled me down so heavily I felt the shocking need to crawl into bed and sleep.

I made a mental list. It was a short one: call my parents, and call Jess in Greece. I had no idea what time it was there.

Back at the unit, there were other officers waiting, some already inside. They took my phone. They bagged Sarah’s hairbrush. They questioned me relentlessly, through the night and into the early morning, until I could barely form a coherent sentence, let alone recall what I’d said before. They also gave me updates on their investigation, which were not reassuring.

Footage from the cameras in the laneway proved inconclusive. It was difficult to find a clear view of the street and the pedestrians because every angle was obscured by vendors’ awnings and umbrellas. Every vehicle registration matched locals, vendors or visitors. No witnesses had come forward.

Sarah had simply vanished, as if she’d never been there.

The one thing the footage did prove was that I had spent roughly five minutes waiting in the side street, playing cat and mouse with my missing child, which at least gave police an approximate time for her possible abduction. Five minutes, waiting for her when I could have been looking. I should have remembered more: the exact time she disappeared, faces of passing people, cars in the parking lanes. But I simply waited, thinking she’d be back at any moment. I’d dragged Sarah all the way there, clenching her tiny hand in my fist, and then I’d let go.

Five minutes, wasted.

I won and I lost.

By midmorning the questions had ceased and an officer had returned my phone. I was encouraged to rest. Instead I spent hours in my bedroom making desperate calls, while a revolving shift of police officers crowded the unit. My neighbours had been woken during the night and questioned. Jess had promised she would be on the first flight home and my parents were on their way. Each conversation only made Sarah’s absence more painful and real, and I couldn’t help but replay, over and over, what my mother had said when I managed to choke out that Sarah was missing.

What are you saying, Abbie? Are you telling me you lost her?

That she was distraught, but not shocked, was another twist of the knife.

My phone battery eventually died. I put it on charge and picked up a book from my bedside table. I’d read the first half, about a woman, an amnesiac, who woke each morning with no memory of her life. How awful, I’d thought, to forget everything while you slept. My bookmark was one of Sarah’s drawings, given to me the day before. Now, when I unfolded the paper and looked more closely at her characteristic bobble-headed figures and fussy colouring in, the drawing seemed like an omen.

Sarah: smiling and dancing.

Me: standing over her, faintly menacing, hands on hips.

When I finished that book almost a year later, I knew intimately how terrible it was to wake each morning and remember.

NOW

Twenty minutes before we were married, Murray and I had sex behind the box hedge separating the backyard from the winter creek that ran behind our house. I pondered whether it was bad luck to screw before the wedding, but shrugged it off – I should be living in the moment, not dwelling on the past or thinking about what might lie ahead. It was 2010, the year of the Haiti earthquake, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, WikiLeaks, the Chilean mining accident, the Times Square bomber, and Lady Gaga’s meat dress.

Sarah had been missing for almost six years. It didn’t make the papers.

On the other side of the hedge there were seventy-two white chairs, two blocks of six by six; in the middle, an aisle strung with fake ivy and real roses; at the end of the aisle, a wrought-iron gazebo, still tacky after two coats of white enamel paint. Seventy-odd people – it wasn’t many for a second wedding and a combined family, but we invited people we liked, plus a few we didn’t. Blood was blood. Our guests were seated and waiting. Not my mother, Martine, who’d staked out her chair front left-of-centre and announced, since we were taking so long to get started, she was going inside to open a second bottle of champagne.

The sex wasn’t sexy and we gave up after a few minutes, laughing.

‘Be seeing you,’ Murray said.

We kissed.

Murray dashed around to the front door and sneaked into the spare room.

I entered the house through the sliding door on our bedroom deck, switching on the ensuite lights to check myself in the mirror. The heavier-than-usual make-up was making me sweat. My curly blonde hair had been slicked down and pulled back, my body waxed, tweezed and squeezed into a sage-green halter-neck dress that made my swimmer’s shoulders seem gargantuan. I looked stiff and unnatural, like a tomboy who’d had a makeover.

I plucked a fistful of tissues to blot my nose and cleavage, counting down from a hundred until my breathing steadied. At the last moment, I switched the matching green heels for well-worn flats, to give me a better chance of staying on my feet.

Jess was waiting in the kitchen, ready to walk me down the aisle. Four years younger and two inches taller, she was just shy of six feet when she drew herself to full height, which was always. Her hair fell in loose ringlets to the middle of her back and she wore a sleeveless linen shift the colour of milky tea. The dress was already wrinkled, but Jess wouldn’t care. My twin in looks but not in temperament, she stood with her hands on her hips and her feet apart, as if braced for a tackle.

‘Morning glory?’ Jess smirked.

‘It’s almost three in the afternoon.’

She reached behind my ear. A leaf materialised. ‘You have hedge in your hair.’

I patted the twist at the nape of my neck. ‘It must be from the bouquet.’

‘He’s a good guy, Abbie.’ A bold statement from Jess, who didn’t believe there were good men, only those who hadn’t been caught. ‘Relationship goals.’

‘My last relationship goal was to have a musician who looked a bit like Rick Springfield write a song that sounded a lot like “Jessie’s Girl”, for me,’ I said. ‘I’m punching way above.’

Murray and I had planned a simple wedding, which meant we’d hardly planned at all. I booked the celebrant, Deirdre, and the cake and chairs online. I sent invitations by email and organised a cheap caterer. Murray repainted the gazebo, set up the chairs and filled an old bathtub with bottles of wine and champagne. There would be drinking, dancing and insulting speeches, and after everyone had gone we’d fall into the same bed, watch a late movie we’d seen before, make love missionary-style and fall asleep straight after, the way we’d been doing it for four years.

Nothing would change, especially not my last name. Morgan, not Lucas – so Sarah could find me.

Jess checked her watch. ‘How fashionably late are you planning on being?’

I glanced outside. Our guests were fanning themselves: it was over thirty degrees despite being midway through autumn.

‘Let’s get this over with,’ I said.

Jess’s expression darkened: on cue, Martine stood in the doorway, mirroring my sister’s stance. Her mother-of-the-bride outfit was the same beige lace-trimmed suit she’d worn to my father’s funeral two years ago. Her cheeks were stained raspberry and wisps of greying blonde hair had slipped loose from her bun. Even ageing and tipsy, she was formidable.

People said that about the three of us, that we were women of strong bearing, big bones. But I didn’t feel strong today – I felt as if, with the right pitch and frequency, I might shatter.

Martine raised her glass. ‘What are you standing around for? Are you ready?’

I nodded. I took my mother’s half-glass from her and threw it back, partly for show, partly to keep her from drinking more.

‘Where’s Murray?’ Jess asked. I shrugged. ‘He’s coming.’

Martine cackled. ‘Maybe he’s changed his mind.’

‘Maybe he’s changing his pants,’ Jess said under her breath. She made an obscene gesture with her tongue. ‘Come on, we’re all adults here.’

In any exchange, even a good-natured one like this, Martine tended to hit below the belt, Jess aimed for shock value and I tried to distance myself from the indignity of it all. Martine always said I wasn’t invested, that there was a picture of me under the word ‘egocentric’. She said I was careless with people.

I didn’t think that was true. Not anymore.

‘Where’s my wife?’ Murray boomed. He grabbed Jess by the waist and spun her around. ‘Wait. Wrong sister.’

I smiled and waited. Martine would say something cruel and Murray would shoot her down. I depended on it. Three, two, one…

‘Your second wife,’ she said. ‘And almost young enough to be your daughter.’

‘My last wife, if she’ll have me,’ Murray said. ‘Count me blessed.’

Martine huffed and went outside to take her seat.

‘Marry him before I do,’ Jess said, knocking me with her elbow.

Edie opened the sliding door. ‘Dad? We’re melting out here. Cam has already taken off his shirt.’ She blew me a kiss. ‘Abbie, you look beautiful.’

‘Don’t you make me cry, kid.’

I did anyway.

Deirdre was at least seventy, twenty years older than the picture on her website, but she was professional and expressionless and perfect. She beckoned Murray to stand next to her under the gazebo. He took his time, shaking hands and kissing cheeks on his way down the aisle.

Jess held me back in the kitchen for longer than I wanted.

‘Wait,’ she said. ‘Let everyone sit back down.’

I stood by the door, fiddling with the fine gold chain around my neck. My hands jerked and shook. If I waited too long and something went wrong, it would be my fault. I was constantly looking for ways to avert disaster – not obsessively, just countless minute calculations and adjustments that made my worries bearable, like making sure Edie and Cam were safely home before I went to sleep. Vigilance.

Jess stilled my hands. ‘Abbie, stop.’

‘I’m fine.’

‘It’s okay to be happy.’

‘I know.’

‘Do you?’

I’d asked Jess to give me away. I hated being the centre of attention, and my sister commanded it. She walked beside me, her arm hooked through mine. I held her hand so tightly I squeezed the blood from her fingers, but she neither flinched nor complained.

I half-registered the many faces on my way down the aisle, most of them Murray’s family and friends. Sherri, Murray’s ex-wife, was sitting with Edie and Cam, and I wouldn’t have had it any other way. My own guests probably totalled fifteen: aunts and uncles, a couple of cousins, and Tara, another instructor from the swim centre where I worked, who had brought her partner, Cleo. I noted the unoccupied seat next to Martine, and assumed she was displaying uncharacteristic sentimentality by reserving it for the ghost of Dad.

It was then that I saw her, Cassandra Albright, second row from the front. I knew the familiar slant of her posture, her determined chin. She was alone. She must have come all the way from Sydney – I’d sent an invitation to be polite, but I didn’t think she’d turn up. We had spoken just once in the past twelve years, the day after my father’s funeral, two years ago.

Cass brought everything back. Cass was there when my life switched tracks; she was not there when it completely derailed.

I returned her tentative smile.

Jess gave me a moment to recover and gently pulled me along. I stumbled up the steps, glad I’d taken off the heels. Deirdre took our hands and crossed them over each other. Rather than the usual we are gathered here today she said welcome to this most glorious union, and I stifled a hysterical giggle.

I focused on Murray. As he fumbled for the rings in his pocket, I felt the awful weight of knowing that, if we were fortunate enough to reach old age, and given women tend to outlive men by seven years, I might spend up to thirty years of my life without him. The thought had no place here, but I was intimate with foreboding. Now it was a guest at my wedding.

We’d written our own vows. Mine were heartfelt, delivered in a low, tremulous tone that had everybody straining forward to hear. Murray spoke loudly and with conviction but, as always, he made it sound as if a punchline was coming.

‘Second time lucky for this old man,’ he said, and there was a rumble of laughter.

We exchanged rings. Murray slid the band over my knuckle.

I glanced at the chair where my father should have been. The seat was now taken: Sarah’s doll Annie, arms and legs akimbo, head drooping like a sleeping child. She had loved that doll – fed it, slept with it, carried it everywhere, except the day I’d made her leave it behind.

Jess and I locked eyes. Her hands flew to cover her mouth.

Deirdre cleared her throat. ‘Should I repeat the last bit?’ she said through her teeth.

I shook my head.

She pronounced us man and wife. I don’t remember how we kissed, probably close-mouthed and passionless. My lips were dry, my body stiff with anxiety.

Martine went inside with the doll straight after the ceremony. She’d made her point. My mother was my constant reminder that my child was still missing, that my time hadn’t been served.

I barely remember accepting congratulations from our guests – at least not until Sherri approached. We were opposites: she was fifteen years older, olive-skinned, dark-haired, small-boned, always impeccable in her manner and dress. We shared an easy friendship because Sherri made it easy.

Murray’s arm tightened around my waist and he swung Sherri around with the other. Was it wrong that he still looked at her like that? Was it strange that I didn’t mind?

Sherri pecked his forehead. ‘You lucky man.’ She cupped my cheeks. ‘You look gorgeous, Abbie. But what happened up there?’

‘I had a moment,’ I said. ‘I’m fine now.’

Murray sighed. ‘Martine.’

Sherri nodded. ‘What can I do?’

‘Nothing,’ I told her. ‘Eat. Drink. Be Sherri.’

She smiled. ‘I have an early flight, but I’ll do my best.’

Murray wandered away to speak to a work colleague, and I took a flute of champagne from the tray Edie was holding. She was the image of Sherri, but like her father in personality, with grand plans to take over Murray’s veterinary practice when he retired. I envied her drive and focus at only nineteen. Her brother, Cam, two years older, somehow managed to juggle a thriving social life, football, tennis, more than one girlfriend and an engineering degree.

Blinking away tears, I surveyed the garden, our guests, the way everything glowed a sunny yellow. At Edie and Cam’s ages I had been a pregnant teen and a single parent on welfare.

‘Abbie.’

My heart skipped – I wasn’t sure if it was gladness or nerves. ‘Cass. Thanks for coming. It’s good to see you.’

‘Of course,’ she said. ‘Wouldn’t have missed it.’

‘Did you fly down?’

‘I drove. I’ll head to Athena Bay tomorrow to visit Mum and Dad.’ She laughed. ‘Funny how I still think of it as home – I haven’t lived there for almost half my life.’ She took in my bright eyes. ‘You look happy.’

‘I am.’

She gave me an awkward hug and I returned it, knowing how precarious these moments of friendship could be.

‘I’ve missed you,’ I said.

‘Same.’

‘I’m sorry it’s been so long.’

‘Me too.’

Someone turned up the music.

‘Where should I put this?’ She held an envelope. ‘It’s a gift card. I know you said no gifts, but seriously, nobody ever means that.’

We laughed.

‘Thank you. There’s a wishing well on the bridal table.’ I looked down at my not-wedding dress. ‘I’m a bride. Who’d have thought?’

Cass grinned and looked twenty again. ‘I’ve been close a couple of times but you beat me to it.’

‘Where are you staying? I want to hear all about – you know, we’ve missed so much.’

‘Oh.’ She seemed embarrassed. ‘I was going to sleep in my car.’

‘We have a sofa bed.’

‘But it’s your wedding night.’

I shrugged. ‘We’ve been living together for years. Nothing is going to change.’

*

It was midnight. Many of our guests had stayed longer than expected and I was disappointingly sober, still doing the goodbye dance at the door.

Jess was taking Martine back to her room at a nearby hotel. It was her gift to me, she said, and we hugged long and tight as they were leaving. I moved to hug my mother too, but she swooped in and out of my embrace, our bodies barely touching. Her outfit had wilted; her cheeks were dry as paper. She looked old. I felt sorry for her, which would probably upset her far more than me thinking she looked old.

‘Congratulations, Abbie,’ she said.

‘Thanks for coming.’ I watched her snake sideways down the steps, gripping the balustrade for balance. ‘Why does she hate me so much?’ I whispered to Jess.

‘Because you pretend you don’t need her,’ she said.

‘You don’t need her.’

‘But I pretend that I do.’ Jess squeezed my hand. ‘I’ll take the gorgon now. You take your husband to bed.’

‘I haven’t seen him for a while. He’s probably already there.’

Jess smiled. ‘I love you.’

‘Love you too.’

I locked the door behind them, checking it three times before glancing into our bedroom. As suspected, Murray was flat on his back, snoring. I took a spare pillow and a quilt from the linen cupboard in the hallway and carried them to the lounge room.

Cass was sitting on the couch, nursing a cup of tea. She’d cleared away the last of the wine glasses and brought the wishing well inside.

I dropped the pillow and quilt on the sofa bed opposite and sat next to her. ‘I feel terrible. Was I supposed to open the cards in front of the guests?’

Cass sipped and shrugged. ‘I’m not up with wedding etiquette, but feel free to ask me anything about debt collection.’ She pulled the wishing well across the table. ‘You could open them now.’

‘Sure. Help?’

She chose an envelope, broke the seal with her fingernail, drew the card and placed it on my lap, open. ‘There’s a hundred bucks.’ Rip. ‘Another hundred here.’

‘People have been so generous. We don’t need anything.’

‘I know. I mean, look at this place.’

Murray’s home – our home – was beautiful: a restored 1920s villa set on a wide street in the kind of leafy, affluent suburb that didn’t brown off in summer. It had a wide return verandah and a rambling quarter-acre garden, and our neighbours were hidden behind wrought-iron gates, tall brick walls and high hedges. Sherri’s classy touch was evident everywhere, which should have been uncomfortable but wasn’t.

‘What does he do, your man?’ she asked.

‘He’s a vet. A very good one.’

‘We wanted to be flight attendants, remember?’

‘Until I realised I was afraid of flying.’

Cass reached for another envelope. After a pause, she said, ‘You were afraid of everything, Abbie.’

I tensed. ‘Because we took so many risks.’

‘We were young.’

‘We were stupid.’

‘We had fun.’

We had sex with strangers and played Russian roulette with pills. I had a baby. My child was abducted. I was little more than a child myself when it happened. None of it was fun.

But I just said, ‘Well, that depends on who’s telling the story.’

Cass held up a card and another couple of fifty-dollar notes. ‘It was nearly thirteen years ago. You’re still angry.’

‘I’m not angry. I’m scared. It never stops.’

It was like having a floater in my eye – I could see beauty all around, but this thing was there, clouding my vision, making everything ugly.

Cass leaned close and slung her arm around my shoulder. ‘I don’t know what to say except I’m sorry. This was meant to be a happy day.’

‘I am happy. That’s why I feel like shit.’ I gave a strained laugh and wiped my eyes. ‘Clearly I haven’t consumed enough alcohol.’ I chose the next envelope because it was small, plain, and it seemed lost among the bulk of the rest. It was tucked, not sealed, nothing written on the front. Inside was a piece of A4 copy paper, folded twice. I unfolded the paper and smoothed the creases.

My breath caught in my throat.

Over the years, I had become used to Sarah’s drawings turning up when I least expected – in drawers, tucked between the pages of books, among her old toys and games. Each one was a cursed reminder, and a gift. In this drawing we were wearing bell-shaped gowns, holding hands. I had something approaching a smile on my face, and Sarah had accurately portrayed her own features, with her direct stare and Frida Kahlo-esque brows.

Along the top of the page were the words: Happy Wedding Day, Mummy.

Written by an adult hand, made to look childish? Sarah had never called me Mummy. She was born a hundred years old. How typical of Martine to keep this precious thing from me until now, and to ruin it by scribbling all over it.

‘What is it?’

‘It’s nothing.’ I shuffled the paper and envelope with the rest and gathered them to my chest. ‘Help yourself to anything you need. I’ll see you in the morning.’

Cass reached out to grab my hand. ‘Will you visit? Come to Sydney?’

Like touching a hot stove, my first reflex was to snatch my hand away. I had the sensation of falling down the familiar rabbit hole. None of what happened to Sarah was Cass’s fault, but I had developed irrational ways of coping.

I made a noncommittal sound.

I wouldn’t visit Cass in Sydney. For my own survival, some doors had to stay closed. I was a veteran of disaster, used to life-changing events. Hypervigilant, jumpy, prone to overreaction in a crisis. I knew tragedy could arrive with a bang, but I forgot to pay attention to the hairline cracks and seismic creaks.

You think death is the worst thing – your whole life coming for you. But it’s not the worst.

BEFORE

For six months of the year, the tourists in Athena Bay outnumbered the locals. The rest of the time it was the usual people, too-familiar faces, and the class divide between the business and beachfront property owners, like the Albrights, and the back-street blue-collar locals like us.

What kind of family were we? Sometimes I only knew what we were not – not a family who ate together, like the Rowneys next door, who had six kids and held barbecues every weekend, who played beach cricket and slept in tents in the backyard during summer. Unlike my friends’ houses, ours was never filled with the sound of music and television. We didn’t have people over unless it was a big occasion, like Christmas, Easter, or somebody had died. Our mother read the daily death notices because she didn’t trust any mode of communication that wasn’t in print. She was a committee person: she got things done. I started calling her Martine when I was twelve and she didn’t stop me. Dad was a plumber: he worked six days a week, came home at five, ate sitting in his recliner and fell asleep after dinner with a beer in his hand. We lived two streets back from the postcard-pretty beach, but our parents rarely went there. We had books and rules and timetables, and we had enough freedom, but that, I suspected, was because our parents wanted quiet in the house.

Jess and I were the kind of kids who preferred to be at other people’s houses. That’s who we were.

Cass and I went to the same school; I had sleepovers at her place almost every weekend, slept head-to-toe with her. High school was a breeze. We were decent students, popular, always busy with our local boyfriends, as well as the transient boys of summer. Our weekends were spent defending our hard-earned corner booth at the kiosk and the best spot on the surf beach, and in turn I was protected by my friends – by the town itself – from the world.

Our last summer together in Athena Bay ended in February 1997. Cass went away to university. Everything familiar was suddenly strange; I burned with impatience for the next stage of my life to begin.

Cass had been gone three months when she called late on a Friday night. I’d been out at the surf club, but had left early. We were asleep when the phone rang; my parents stumbled out of bed, clearly assuming the worst, and Jess followed. I grabbed the receiver and pulled the phone cord along the hallway until it was at full stretch. I had to leave the base in the hall and wind the receiver coil underneath the door, so I could close it. I sat on the floor with my back against the wall. Two streets away, the waves slapped the shore.

Jess, just turned fourteen, snuffled at the base of the door like a puppy. ‘Who is it?’ she whined through the gap.

‘Go back to bed.’

To Cass I said, ‘It’s really late.’

She sounded drunk. ‘My flatmate is moving out. I miss you. Will you come?’

‘Come there?’ I lowered my voice. ‘You mean live with you?’

When I opened my bedroom door, Jess was slumped against the wall, staring at me with a look of betrayal. My mother stood with the other end of the cord wrapped around her wrist; she was strung so tight I could have drawn a perfectly straight line along her back.

‘You’re leaving,’ she said.

‘I’m eighteen. I’ll get a job. It’Il be fine.’

‘I give it three months.’

‘I’m eighteen,’ I repeated. ‘You can’t stop me.’

Jess cried.

Cass was as lean and muscled as a dancer, with short, dark hair worn in a bob, pale skin, pierced nose, perfect legs. She met me at the train station. We hauled my two battered suitcases onto a bus and sat on the rear seat, elbows and thighs touching, smiling like idiots.

‘You’re here,’ she said. ‘Things will be okay now. It’s been hell.’

‘What happened with your flatmate?’

Cass shrugged. ‘She had a problem with the house rules.’

Our unit was close to a main road. The kitchen was little more than a kitchenette; any more than four people and the lounge room was overcrowded. There was an enclosed yard, barely big enough for two deckchairs and a wall-mounted washing line, and a mould-ridden showerbath combo in the bathroom. Rising damp had lifted tiles and curled vinyl, but when Cass had complained the landlord threatened to raise the rent.

It was a shithole, but it came semi-furnished and now it was ours.

Cass had the main bedroom. Mine was three by three metres with a draughty window that played like a flute and a ceiling hatch above my double bed. There were dirty handprints around the edge, as if someone lifted the cover at night and looked down at me while I slept. When I had trouble falling asleep, I counted the sounds of gear changes instead of sheep.

Here we were, fresh out of home, leaving behind bedrooms with posters of Kurt Cobain on the walls, and drawers half-full of cheap cotton underwear and pharmacy brand make-up. Cass had started her Bachelor of Business. Against my parents’ wishes, I’d deferred my place at teachers’ college because I wasn’t sure it was what I wanted. Ten years in a surf lifesaving club and six months as a checkout operator were my only qualifications, but within a week I’d found a casual job as a junior swim-school teacher.

Ambition seemed like something I could leave in my pocket for later.

I borrowed Cass’s clothing and emulated her style. I cut my hair into a bob like hers, dyed it dark, blow-dried it straight, pierced my nose and lost nine kilos. We looked so alike people took us for sisters. With practice I even danced like Cass, but the nineties club scene wasn’t kind to me. I was beach-born. I needed a solid month of sun to look healthy and waves up to my waist to hide my wide hips. Living like nocturnal creatures turned my skin yellow; the undyed roots of my hair showed green. I missed my rent payments to pay for drugs I rarely took, to earn membership to a scene that didn’t fit, to keep up with a friend who’d outgrown me so fast she seemed like a changeling.

Cass received top-up money from her parents.

Mine were watching me paddle from afar, hoping I’d sink.

Cass kept a glass jar filled with loose change in a kitchen cupboard – sometimes I took a few dollars. Not too much for her to notice, but enough to afford a pack of cigarettes or to pay for bread and milk if it was my turn. She brought home guys who smoked weed inside and wandered around half-naked. She ignored the dishes in the sink until we either ran out of plates or I gave in. I’d go to wash my clothes and find hers twisted in the basin, stale and stinking.

‘What are the house rules?’ I asked.

I knew the answer. There weren’t any.

‘No guys we don’t know, okay?’

She agreed, but did as she wanted.

In the beginning, I only had Cass. Home was over two hundred kilometres away and, apart from Michael Tate, another instructor from the swim school, I was too shy to make new friends of my own. Cass had fallen in with a group from uni – Karla, Reno, Fiona and Brent. Others came and went, but the six of us hung out a lot.

Fiona and Brent were an on-again-off-again couple, both still living with their parents. Brent disappeared for hours at the clubs, and when he returned they’d fight. Fiona cried a lot. Cass and I counselled. They always ended up together again, making up on our couch, and we forgave them for the drama.

Karla was on exchange from Berlin. She was living on campus and appeared mysterious and terminally bored. While we danced, she watched, repelling the boys with her cold stare, sneaking glances at the girls. Cass admitted they’d kissed one boozy night, but to my knowledge Karla never showed any other sign of being a sexual being. She ate our food, slept on our couch and used our toiletries, but she was the perfect house guest: she’d slink away quietly leaving the dishes washed, the couch cushions plumped, and intricate doodles of the solar system on the notepad next to our phone, which she used frequently to call home. She always left money to pay for the calls.

Reno was even more of a mystery than Karla. Cass found him fascinating – she said he looked like Marilyn Manson without the make-up, and she suspected he had the IQ of a genius. He also had the best drugs and a seemingly endless supply of cash. He was the one with the contacts and a free pass into every club, and the only one of us with a car, a red 1976 BMW 5-series with ripped leather seats and a machine-gun exhaust.

‘Reno fancies you,’ Cass told me one morning. ‘We have to pay extra this week for the gas bill. And we’re out of milk. Do you want Lucy or Molly for the weekend?’

‘Molly,’ I said. ‘How do you know?’

‘Reno told Brent. Brent told Fiona. I’m telling you. It would be so great if you two got together.’

‘I don’t think we have much in common,’ I said. ‘He’s not really my type.’

I gave Cass my last hundred and was lucky enough to get Michael’s classes while he was sick. I made it through the next week by offering to clean our elderly neighbour’s unit, the following week by cashing in stolen empty bottles and cans. I pawned a gold chain my parents had given me for my eighteenth, but when I went to get it back it had been sold.

During the day, I reassured new mothers while I held their squirming toddlers in the pool. I blew in the kids’ faces and dunked them, dodging tiny fists as they hit and kicked and paddled like frightened puppies. At night I followed Cass: to bars and clubs, to share houses filled with loud music and overheated bodies, along quiet streets as we found our way home in the morning.

Work, watch TV, sleep, dance, work, sleep – it was freedom and independence of a sort, as Cass had promised when she summoned me to the city. Here was the world, ready to explore, but it turned out my greatest ambition was to deliver a lie convincing enough to stay home, to have the unit and the TV to myself.

They were my friends, and they were not. I hardly knew them, I didn’t trust them, but Cass included them in everything. I complained that we never did anything together anymore, just us, the way it used to be.

Cass bloomed. I began to fade.

One afternoon, a few months after I’d moved in, Cass was outside watering the pot plants when Michael dropped me home after work. We had been taking classes in adjacent lanes for a couple of months. When he noticed I caught the bus after our shift he started offering me rides.

I found him shy but harmless. He reminded me of Lenny from Of Mice and Men: huge, shaggy and lumbering – not exactly slow, but not a quick thinker. The kids loved him. Cass thought he was weird.

I sat in the car for a few minutes making polite conversation – I couldn’t invite him in, not with Cass eyeing us from the porch, semi-naked and openly hostile.

‘She mustn’t feel the cold,’ Michael said, and he wasn’t trying to be sarcastic.

‘Probably.’

‘I don’t think she likes me.’

‘Oh, she just doesn’t know you.’

I got out, slammed the door and tapped the roof twice in thanks.

Cass watched Michael drive away. ‘He’s one strange cat, Abigail.’

‘No stranger than half the guys you bring home, Cassandra.’

‘You must give off weird pheromones. You always did attract the losers.’

It was the first time I realised that my version of events and Cass’s weren’t quite the same – like going to your high school reunion and finding out your perceived popularity was an illusion. It wasn’t the losers I attracted, it was the loners. Guys who didn’t hang in packs, who broke the rules. Or were they the same thing?

‘Don’t encourage him,’ Cass said. ‘You’re too nice.’

‘Encourage what? He just gave me a ride home.’

She pinched off the hose and aimed the nozzle at me. ‘Don’t even.’

‘Is that a dare?’

Cass came after me and I ran until the hose reached its full length. She kept me standing out on the street, dripping, while she laughed and laughed.

I took a few days’ leave and travelled home to visit, once.

I went to my old haunts and caught up with friends, but I’d lost my sense of belonging. Everyone had slipped seamlessly into adulthood while I was stuck in between. Jess was still mad: she barely spoke except to announce she’d taken over my bedroom as her study room – I’d have to sleep on the couch. Dad was either at work or drinking beer in his shed, and my mother served her regular hot meals but maintained her cold distance, slopping food onto my plate and furiously shifting my belongings from the couch to a corner of the lounge room, where they wouldn’t offend her.

‘Why does everyone hate me?’ I whined to Dad. ‘Jess is being such a brat. It’s like you don’t want me here.’

He said, ‘Do you mean we should all stop what we’re doing and treat you like you’re on holiday?’

‘Martine isn’t even speaking to me.’

‘You’re as stubborn as she is.’ He smiled wryly. ‘It’ll pass. It started when you told her she couldn’t control you and it’ll stop when you realise that to her it isn’t control, it’s love.’

At dinner that night, Dad asked pleasantly, ‘So how are you and Cass finding life in the big city, Abbie?’

Before I could answer, Martine said, ‘They’re probably doing hard drugs and having unprotected sex all over the place.’

Jess burst into laughter.

Dad left the table.

The next morning I packed my bag and went back to Cass.

When Reno and I eventually hooked up, it was a classic case of peer pressure and the euphoria of Reno’s pills. Disorienting, awkward and unpleasant, both times. He wasn’t the first guy I’d had sex with, but he would be the one I’d never forget.

The second time he stayed the night, I woke early, hungover and overwhelmed with regret. I decided I found him repulsive: his long, pale, almost hairless body, and the way he ground his teeth in his sleep. I lay there unmoving for an hour, facing away and feigning sleep. I sensed he was awake too.

A hand slid across to cup my hip, and I sprang from the bed. I couldn’t cover my nakedness fast enough.

‘You don’t have to stay.’

He uncurled from my sheets like a lazy cat. ‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean, it’s okay to go. I won’t be upset.’

I went to the kitchen to make coffee. A minute later I heard the shower running.

By the time the kettle had boiled, he was dressed and standing too close behind me in the small kitchen. I found his height and presence intimidating, his blown pupils unsettling. I felt his breath on my neck. Cass wandered in, smirking.

I sighed in relief but didn’t turn around.

Reno read the room and left.

He had used my toothbrush and towel and left them both in the sink, wet. For four days straight he called the landline two or three times a day, until I unplugged it and signed up for my first mobile phone plan. Another expense I couldn’t afford. He called Cass instead, and she translated his increasingly aggressive messages to the whiteboard.

‘Did something happen?’ she asked.

‘No. Not really.’

‘He likes you.’

‘I can tell that.’

‘You’re harsh, Abbie.’

‘God, I’m too nice, I’m too harsh – which is it? I don’t fancy him.’

‘Then why did you hook up?’

Why did I sleep with anybody? To fulfil other people’s expectations. Out of boredom. For comfort. Never because I was in love. Because, when I felt the heat of another’s skin, I wasn’t invisible and I wasn’t alone.

NOW

Two days after our wedding, Murray was called in to cover the emergency shift at the animal hospital until the regular night vet returned, and we postponed our honeymoon.

We settled into the familiar and frustrating night-shift routine – meeting briefly between the sheets in the early morning, like a couple having an affair. It was the only time I felt truly safe: curled into his heat, feeling his big hands on my body, smelling the hint of antiseptic that clung to his skin even after he’d showered.

It was his second week of night shift, eight days after the wedding. We had made love, and he was already slipping away into exhaustion and sleep. I lifted his heavy arm from my waist and tried to slide from the bed without disturbing him.

He stirred and pulled me closer. ‘Stay.’

‘I’m driving Edie to uni,’ I said. ‘She has a meeting first thing.’

‘Edie can catch the bus.’

‘I promised.’

Murray groaned and rolled onto his back. ‘You’re a disgrace to wicked stepmothers everywhere.’

‘I’ll come back after,’ I lied.

Murray stared at the ceiling. He seemed lost in reflection.

‘Bad night?’ I asked.

He nodded. ‘Some Pentecostal twit brought in his dachshund. Said he thought she’d eaten rat bait, but when I wanted to put in an IV and keep her overnight he said he’d take her home and pray for divine healing.’

‘What did you do?’

‘Nothing I could do. No one will ever thank you for telling them how to look after their animals or their children.’ He checked his phone. ‘What day is it? Do you have classes?’

‘It’s Monday. I have Nippers and Dolphins in the afternoon.’

‘Driving across town for two classes?’ he said. ‘You don’t need to work. You could quit.’

‘I love teaching kids to swim. You know that.’

I smiled to hide my annoyance and slid out of bed. I took a quick shower and started getting dressed. Out of habit, I popped a contraceptive pill from the packet and put it under my tongue. At the same time, I pulled on a clean pair of underwear, one-handed.

‘Multitasking, like clockwork,’ he said.

I smiled. ‘Go to sleep.’

‘Speaking of clocks – what if you stopped taking them?’

I froze. ‘What are you saying?’

He patted the bed. ‘I’m sorry, that was clumsy.’

I went over to him and he caught my hand.

‘Am I too old to be a father again?’